Abstract

Introduction

The aim of the current study was to assess the reliability, validity and psychometric properties of the Greek translation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies- Depression Scale (CES-D).

Methods

40 depressed patients 29.65 ± 9.38 years old, and 120 normal controls 27.23 ± 10.62 years old entered the study. In 20 of them (12 patients and 8 controls) the instrument was re-applied 1-2 days later. Translation and Back Translation was made. Clinical Diagnosis was reached by consensus of two examiners with the use of the SCAN v.2.0 and the IPDE. Statistical Analysis included ANOVA, the Pearson Product Moment Correlation Coefficient, Principal Components Analysis and Discriminant Function Analysis and the calculation of Cronbach's alpha (α)

Results

Both Sensitivity and specificity exceed 90.00 at 23/24, Chronbach's alpha for the total scale was equal to 0.95. Factor analysis revealed three factors (positive affect, irritability and interpersonal relationships, depressed affect and somatic complains). The test-retest reliability was satisfactory (Pearson's R between 0.45 and 0.95 for individual items and 0.71 for total score).

Conclusion

The Greek translation of the CES-D scale is both reliable and valid and is suitable for clinical and research use with satisfactory properties. Its properties are similar to those reported in the international literature. However one should always have in mind the limitations inherent in the use of self-report scales.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Center for Epidemiological Studies- Depression Scale (CES-D) [1] is a well known and widely used self-rating scale for the measurement of depression. Along with the Beck Depression Inventory [2] and the Zung Depression Rating Scale [3], these are the most popular self-administered instruments for the assessment of depression. These scales are supposed to be used as screening tools rather and not as substitutes for an in-depth interview [4]. They can also be an efficient tool for screening patients for depression [5] and have been used successfully for many years in the primary care setting. Higher scores on this scale are indicative of more severe depression [6]

The CES-D is a self-reporting instrument and was originally developed in order to assess depression symptoms without the bias of an administrator affecting the results. The items in the CES-D scale may also help patients begin to discuss previously nebulous symptoms, especially those patients who present with physical symptoms of depression such as headache or insomnia. CES-D consists of 20 items that cover affective, psychological, and somatic symptoms. The patient specifies the frequency with which the symptom is experienced (that is: a little, some, a good part of the time, or most of the time) [7].

The aim of the current study was to assess the reliability, validity and psychometric properties of the Greek translation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies- Depression Scale (CES-D)

Material and Methods

Material

Forty patients (25 males and 15 females) aged 29.65 ± 9.38 years (range 18-55) suffering from Major Depressive disorder according to DSM-IV [8] and depression according to ICD-10 criteria [9], and 120 normal controls (71 males and 49 females aged 27.23 ± 10.62 years (range 18-51) entered the study. In 20 of them (12 patients and 8 controls) the instrument was re-applied 1-2 days later.

Patients and controls were free of any medication for at least two weeks and were physically healthy with normal clinical and laboratory findings (Electroencephalogram, blood and biochemical testing, thyroid function, test for pregnancy, 12 and folic acid).

Patients came from the inpatient and outpatient unit of the 3rd Department of Psychiatry, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, General Hospital AHEPA, Thessaloniki, Greece. They were consecutive cases and were chosen because they fulfilled the above criteria.

The normal control group was composed of members of the hospital staff and relatives of patients. A clinical interview confirmed that they did not suffer from any mental disorder and their prior history was free from mental and thyroid disorder.

All patients and controls provided written informed consent before participating in the study.

Method

Translation and Back Translation was made by two of the authors, one of whom did not knew the original English text. The final translation was fixed by consensus.

Clinical Diagnosis was reached by consensus of two examiners. The Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) version 2.0 [10,11] and the International Personality Disorders Examination (IPDE) [12,13,14] were used. Both were applied by one of the authors (KNF) who has official training in a World Health Organization Training and Reference Center. The IPDE did not contributed to the clinical diagnosis of depression, but was used in the frame of a global and comprehensive assessment of the patients. The second examiner performed an unstructured interview.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) [15], was used to search for differences between groups. The Pearson Product Moment Correlation Coefficient R was calculated to assess the test-retest reliability. Principal Components Analysis (Varimax Normalized Rotation) was performed, and factor coefficients and scores were calculated. Finally, Discriminant Function Analysis was performed as well.

Item Analysis [16] was performed, and the value of Cronbach's alpha (α) for CES-D and its factor subscales was calculated. Receiver Operator Characteristic Curves (ROC curves) and histogram of frequencies were created as well.

Results

The calculation of sensitivity (Sn) and specificity (Sp) at various cut-off levels showed that both variables exceed 90.00 at 23/24, with 109 controls and 36 patients correctly classified. Eleven controls and 4 patients were classified into a wrong diagnostic group (table 1). Receiver Operation Curve Analysis (figure 1) confirmed these results.

Chronbach's alpha for the total scale was equal to 0.95, and this is a very high value, suggesting that the CES-D scale reflects a single structure.

The histogram of CES-D scores in control subjects reveals that they do not follow the normal distribution in this population, but manifest a skew towards lower values (figure 2).

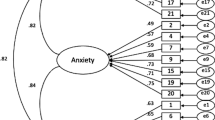

The factor analysis of cases (varimax normalized rotation) revealed three factors (table 2). The first one includes items No 3, 4, 8, 12, 14 and 16, largely reflects a factor of positive effect, and explains 22% of variability. The second one includes items No 1, 11, 15 and 19, largely reflects a factor of irritability and problems with interpersonal relationships, and explains 13% of variability. The third factor includes items No 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14, 17, 18 and 20 and reflects depressed affect and somatic complaints. It explains 31% of total variability. Factor loadings and coefficients are shown in table 2. All three factors explain 66% of total CES-D variance.

Chronbach's alpha for the individual factors (subscales that include the items that load in each one) was excellent. The factor 1 items had alpha equal to 0.91, those of factor 2 equal to 0.76 and those of factor 3 equal to 0.94.

Depressed patients did not differ from controls in age. On the contrary they differed in every CES-D individual item score and total score (p < 0.001- table 3). It is very interesting that the two groups did not differ in the scores of any of the factors that emerged. Only factor 3 showed a tendency towards significance (table 3). However the two groups differed in all scores that derive from the sum of items that group under each factor (p < 0.001).

The test-retest reliability proved to be satisfactory. Individual items had good Pearson correlation coefficients with lower for item No 1 (R = 0.45) and higher for item No 4 (R = 0.95). The coefficient for the total CES-D score was very good and equal to 0.71.

Discriminant function analysis results are shown in table 4. Two separate analyses were performed, with the forward stepwise method, one with individual CES-D items and a second with factor scores. The first one performed excellently while the second one was very poor. The results of the first one suggest that when the D-C equation, that is:

1.43*(It2)+1.01*(It5)+1.13*(It6)+0.63*(It7)+0.94*(It9)+0.65*(It10) +0.96*(It11)+1.07*(It13)-0.61*(It14)+1.32*(It17)-1.20*(It19)-0.83*(It20)

takes values above 9.03, then the subject is a depressed patient. This method correctly classified 98.33% of controls and 87.5% of patients.

Discussion

Self-administered scales heavily depend on the co-operation and reading ability of the patient. On the other hand they save time for the clinician. The reliability and validity of the CES-D has been examined in only a limited number of studies and not many translations of this scale have been published. More, translations are difficult to access because of publication in various languages and local journals. The same is true for other scales, like the Zung Depression Rating Scale [17,18,19,20].

Although the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) is an internationally popular self-rating scale for depression both in community and clinical settings, extend literature concerning its transcultural reliability and validity is limited. The current study reports observations on the reliability, the validity and psychometric properties of the Greek translation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies- Depression Scale (CES-D). The results suggest that this translation is well suited for use in the Greek population with high sensitivity and specificity at the cutoff level 23/24, high test-retest reliability and high internal consistency. Its factor structure is similar to structures reported in the literature.

Apart from the full version, also a 10-, 8- and 4- item versions exist [21,22,23], with comparable accuracy to the original CES-D in classifying cases with depressive symptoms [24].

Because the overlap with symptoms of physical diseases is very limited, the CES-D can be used in physically ill populations [25], so it has been used widely in general medical populations [26,27] and pain patients [28]. Acculturation constitutes a more complex problem [29]. Data indicate that youths who spoke only or mostly English reported lower rates of depression and suicidal ideation, suggesting that acculturation may play a role as well [30]. Also, irrespective of the scale used, a gender difference is found across the ethnic groups, in which girls expressed depressive feelings more than boys [31]. Various papers report on the study of the effect of race and sex [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41], but results are difficult to interpret.

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) has been widely used in studies of late-life depression, but geriatric data are considered insuficient [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50]. Psychometric properties reported are generally favourable [51], but data on the criterion validity of the CES-D in elderly community-based samples are not sufficient.

The Dutch translation manifested satisfactory properties for use in the elderly with Cronbach's alpha 0.80-0.90 [52], which is comparable to the results of the current study, and the Japanese translation proved to be suitable for the detection of major depressive episodes among first-visit psychiatric patients [53].Generally the CES-D has moderate convergent and discriminant validity to detect major depressive episodes among first-visit psychiatric patients and complex methods may be essential [54].

The CES-D was confirmed as essentially unidimensional and robust to minor changes; therefore, it is recommended for use in cross-cultural studies of depression in elderly persons. The original four-factor solution proposed by Radloff was successfully replicated for Australians, showing similar underlying structures as for Americans, Canadians, and Japanese [55].

A moderate correlation between the CES-D and self-esteem and state anxiety. However, a high correlation was obtained between the CES-D and trait anxiety, which suggests that the CES-D measures in large part the related conceptual psychological domain of predisposition for anxiousness [56].

The Spanish trial reported 0.9 alpha,, and the factor analysis showed 4 factors who explain the 58.8% of the variance: "depressed Affect/Somatic", "Positive Affect", "Irritability/Hopelessness", "Interpersonal/Social". The scale shows a 0.95 sensibility and 0.91 specificity to depressive symptomatology detection (according to scores equal or over 9 on HRSD) taking as cutoff scores equal or over 16 on CES-D [57]. The publication of the Spanish version boosted research in Mexican Americans [58,59,60,61,62,63].

In Chinese geriatric patients the correlation with the Geriatric Depression Scale was 0.96 [64]. Chen et al [65] studied whether an instrument developed in the U.S. may identify lower rates of major depression among young Chinese, because its content may not cover culture-specific symptoms of depression. The authors concluded that the lower prevalence of depression was not due to the ethnocentric character of the instrument in the Chinese sample. Similarly, data add to growing evidence that Mexican American youths are at increased risk of depression, and this is not an artificial product of the CES-D [66].

The Italian validation study [67] was carried out in northern Italy with 40 depressives and 40 matched normals and showed that the CES-D is a valid measure in that it sensitively discriminates between depressed patients and normals and presents satisfactory correlations with the observer rating scale (HRSD) in both groups.

Large-scale studies revealed that neither age, gender, cognitive impairment, functional impairment, physical disease, nor social desirability had a significant negative effect on the psychometric properties or screening efficacy of the CES-D [68].

The factor analysis of the Japanese version [69] of the CES-D using data obtained from 2,016 adult employees aged 19-63 years extracted 4 factors for each age group. Depressive affect items did not group into one factor; some were combined with somatic or interpersonal items, and the remainder constituted the smallest factor. These three main factors, 'somatic+depressed', interpersonal + negative' and 'positive affect' were comparable across age groups except for those aged 50-63 years. For those aged 50-63 years, the first two factors were combined into a large 'general dysphoria' factor, suggesting a more unified conceptualization of depressive mood. Although 'positive affect' was stable cross-culturally, it was not related to depressive symptomatology as measured by the other items, for Japanese. The 'interpersonal + negative' appears unique for Japanese, indicating the association of interpersonal relations with depressive mood in Japanese. These results are impressively very close to the results of the current study.

Comparison of the response patterns on the CES-D items between Japanese adolescents and with those of their U.S. counterparts (1,500 junior high school students, aged 12-15 years) showed that Japanese responses to positively worded items markedly differed from those of American adolescents, whereas responses to negatively worded items were comparable in the two groups. This resulted in poor psychometric properties for the CES-D and spurious higher positive subscale and whole scale scores among the Japanese sample. It is possible that Japanese respondents tend to suppress positive affect expression and, thus, the positively worded questioning of the CES-D is presumably inappropriate for Japanese samples [70]. There were differences in patterns of the CES-D item endorsement between diverse ethnocultural groups as indicated by principal component factor analysis of the results of 2200 persons 12-17 years of age. Anglo- and African Americans exhibited similar factor structure, represented by negative affect, positive affect, and psychosomatic symptoms. Two Hispanic groups also exhibited a three-dimensional pattern, but there was a tendency among Hispanic adolescents for somatic symptoms and negative affect symptoms to cluster together. This pattern may indicate a more prominent role of somatic complaints in the presentation of depression among Mexican Americans and other Hispanics [71], and this is similar with the findings of the current study.

Review studies on various self-administered instruments suggest that there is no significant difference between them in terms of performance and overall sensitivity is around 84% and specificity around 72% [72]. These instruments are of particular value in primary care settings because it is clear that primary care providers fail to diagnose and treat as many as 35% to 50% of patients with depressive disorders [73,74]. Depression is one of the most common psychiatric diagnoses in primary care populations [75]; major depressive disorders can be diagnosed in 6% to 9% of such patients. Obstacles to the appropriate recognition of depression include inadequate provider knowledge of diagnostic criteria; competing comorbid conditions and priorities among primary care patients; time limitations in busy office settings; concern about the implications of labeling; poor reimbursement mechanisms; and uncertainty about the value, accuracy, and efficiency of screening mechanisms for identifying patients with depression. Given that 50% to 60% of persons seeking help for depression are treated exclusively in the primary care setting, accurate detection in this setting is important [76] and self -administered instruments may help to ameliolate some of them. Many studies have assessed the effect of feedback of scale scores on physician practice patterns [77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86] and have shown improved recognition of depression with such feedback.

On the other hand, it should be noted that the diagnosis of depression is itself based on symptoms. A patient cannot truly be asymptomatic and have major depressive disorder. Thus, these screening questionnaires are actually being evaluated for their ability to detect unrecognized, rather than strictly asymptomatic, depressive symptoms and disease.

The Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination found fair evidence to exclude the use of depression detection tests from the periodic health examination of asymptomatic people [87]. The American Academy of Family Physicians advises physicians to remain alert for depressive symptoms in adolescents and adults [88]; this policy is under review. The American Medical Association recommends that all adolescents be asked annually about behaviors or emotions that indicate recurrent or severe depression [89].

The agreement between the CES-D scale and the DIS diagnoses of major depressive disorder (MDD) and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) was poor, especially among Mexican-origin patients interviewed in Spanish. Multiple regression analysis revealed that the CES-D scale was positively associated with MDD in all groups. In addition, GAD also was associated with the CES-D scale in Anglos and English-speaking Mexican-Americans but not in Spanish-speaking Mexican-Americans [90].

The results indicate no systematic variation in either reliability (test-retest, internal consistency), dimensionality, or ability of the CES-D Scale to detect clinical depression among Anglos or persons of Mexican origin classified according to language use as Spanish dominant, English dominant, or bilingual. The available evidence suggests that the ability of the CES-D Scale to detect major depression is so limited that further use of the instrument as a screening scale would seem unwarranted, at least in treatment settings [91].

Conclusion

The Greek translation of the CES-D scale is both reliable and valid and is suitable for clinical and research use with satisfactory properties. However one should always have in mind the limitations inherent in the use of self-reporting scales.

References

Radloff LS: The CES-D scale: A self report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977, 1: 385-401.

Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M Mock J, Erbaugh J: An Inventory for Measuring Depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961, 4: 53-63.

Zung WWK: A Self-Rating Depression Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965, 12: 63-70.

Zung WW, Richards CB, Short MJ: Self-rating depression scale in an outpatient clinic. Further validation of the SDS. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965, 13(6): 508-15.

Carrell BJ: Validity of the Zung self-rating scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1978, 133: 379-80.

Marder SR: Psychiatric rating scales. In Kaplan HI, Sadock BJ, eds. Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry/VI 6th ed. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins;. 1995, 1: 619-635.

Carroll BJ, Fielding JM, Blashki TG: Depression rating scales: a critical review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1973, 28: 361-366.

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th Edition, DSM-IV. American Psychiatric Press, Washington DC,. 1994

World Health Organisation: The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders. Diagnostic Criteria for Research. Geneva,. 1993, : 81-87.

Wing JK, Babor T, Brugha T, et al: SCAN: Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry. Archives of General Psychiatry,. 1990, 47: 589-593.

World Health Organisation: Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry-SCAN version 2.0) Greek Version: Mavreas V. Research University Institute for Mental Health, Athens. 1995

Loranger AW, Sartorious N, Andreoli A, et al: The World Health Organisation/Alcohol, Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration International Pilot Study of Personality Disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry,. 1994, 51: 215-224.

World Health Organisation: International Personality Disorders Examination, Geneva. 1995

World Health Organisation: International Personality Disorders Examination, Greek Edition. (Translation: Fountoulakis KN, Iacovides A, Kaprinis G, Ierodiakonou Ch) 3rd Department of Psychiatry, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Greece (unpublished).

Altman DG: Practical Statistics for Medical Research. Chapman and Hall, London. 1991

Anastasi A: Psychological Testing 6th edition. Macmillan Publishing Company, New York,. 1988, : 202-234.

Lopez VC, de Esteban Chamorro T: [Validity of Zung's Self-Rating Depression Scale]. [Article in Spanish] Arch Neurobiol (Madr) May-Jun. 1975, 38(3): 225-46.

Xu MY: [Using the SDS (self-rating depression scale) for observations on depression]. [Article in Chinese] Chung Hua Hu Li Tsa Chih Apr. 1987, 22(4): 156-9.

Chen XS: [Masked depression among patients diagnosed as neurosis in general hospitals]. [Article in Chinese] Chung Hua I Hsueh Tsa Chih. 1986, 66(1): 32-3.

Jegede RO: Psychometric characteristics of Yoruba versions of Zung's self-rating depression scale and self-rating anxiety scale. Afr J Med Med Sci. 1979, 8(3-4): 133-7.

Melchior LA, Huba GJ, Brown VB, Reback CJ: A short depression index for women. Educational and Psychological Measurement,. 1993, 53(4): 1117-1125.

Andersen EM, Carter WB, Malmgren JA, Patrick DL: Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1994, 10(2): 77-

Kohout FJ, Berkman LF, Evans DA, Cornoni-Huntley J: Two shorter forms of the CES-D depression symptoms index. Journal of Aging and Health. 1993, 5(2): 179-

Boey KW: Cross-validation of a short form of the CES-D in Chinese elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999, 8: 608-617. 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199908)14:8<608::AID-GPS991>3.0.CO;2-Z.

Foelker GA, Shewchuk RM: Somatic complaints and the CES-D. Journal American Geriatrics Society. 1992, 40(3): 259-

Callahan LF, Kaplan MR, Pincus T: The Beck Depression Inventory, Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale (CES-D), and General Well-Being Schedule depression subscale in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care and Research. 1991, 4(1): 3-

Schein RL, Koenig HG: The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale: assessment of depression in the medically ill elderly. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1997, 12(4): 436-10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199704)12:4<436::AID-GPS499>3.3.CO;2-D.

Romano JM, Turner JA, Jensen MP: The Chronic Illness Problem Inventory as a measure of dysfunction in chronic pain patients. Pain. 1992, 49(1): 71-75. 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90190-M.

Gallagher-Thompson D, Tazeau YN, Basilio L, et al: The relationship of dimensions of acculturation to self-reported depression in older, Mexican-American women. Journal of Clinical Gerophychology. 1997, 3(2): 123-

Roberts RE, Chen YW: Depressive symptoms and suicidal ideation among Mexican-origin and Anglo adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995, 34(1): 81-90. 10.1097/00004583-199501000-00019.

Takeuchi K, Roberts RE, Suzuki S: Depressive symptoms among Japanese and American adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 1994, 53(3): 259-74. 10.1016/0165-1781(94)90054-X.

Callahan CM, Wolinsky FD: The effect of gender and race on the measurement properties of the CES-D in older adults. Medical Care. 1994, 32(4): 341-

Clark VA, Aneshensel CS, Frerichs RR, Morgan TM: Analysis of effects of sex and age in response to items on the CES-D scale. Psychiatry Research. 1981, 5(2): 171-10.1016/0165-1781(81)90047-0.

Dick RW, Beals J, Keane EM, Manson SM: Factorial structure of the CES-D among American Indian adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 1994, 17: 73-79. 10.1006/jado.1994.1007.

Manson SM, Ackerson LM, Dick RW, Baron AE, Fleming CM: Depressive symptoms among American Indian adolescents: Psychometric characteristics of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Psychological Assessment. 1990, 2: 231-237. 10.1037//1040-3590.2.3.231.

Stommel M, Given BA, Given CW, Kalaian HA, Schulz R, McCorkle R: Gender bias in the measurement properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Psychiatry Research. 1993, 49(3): 239-10.1016/0165-1781(93)90064-N.

Ying YW: Depressive symptomatology among Chinese-Americans as measured by the CES-D. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1988, 44(5): 739-

Aneshensel CS, Clark VA, Frerichs RR: Race, ethnicity, and depression: A confirmatory analysis. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1983, 44(2): 385-

Gatz M, Johansson B, Pedersen N, Berg S: A cross-national self-report measure of depressive symptomatology. International Psychogeriatrics. 1993, 5(2): 147-10.1017/S1041610293001486.

Roberts RE: Reliability of the CES-D scale in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Research. 1980, 2: 125-10.1016/0165-1781(80)90069-4.

Roberts RE, Rhoades HM, Vernon SW: Using the CES-D scale to screen for depression and anxiety: Effects of language and ethnic status. Psychiatry Research. 1990, 31(1): 69-10.1016/0165-1781(90)90110-Q.

Blazer D, Burchett B, Service C, George LK: The association of age and depression among the elderly: an epidemiologic exploration. Journal of Gerontology. 1991, 46(6): M210-

Callahan CM, Hui SL, Nienaber NS, Musick BS, Tierney WM: Longitudinal study of depression and health services use among elderly primary care patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1994, 42(8): 833-

Davidson H, Feldman PH, Crawford S: Measuring depressive symptoms in the frail elderly. Journal of Gerontology. 1994, 49(4): 159-

Hendrie HC, Callahan CM, Levett EE, Hui SL: Prevalence rates of major depressive disorders: The effects of varying the diagnostic criteria in an older primary care population. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 1995, 3(2): 119-

Hertzog C, Van Alstine J, Usala PD, Hultsch DF, Dixon R: Measurement properties of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in older populations. Psychological Assessment. 1990, 2(1): 64-

Himmelfarb S, Murrell SA: Reliability and validity of five mental health scales in older persons. Journal of Gerontology. 1983, 38(3): 333-

Kessler RC, Foster C, Webster PS, House JS: The relationship between age and depressive symptoms in two national surveys. Psychology and Aging. 1992, 7(1): 119-

Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Allen NB: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychology & Aging. 1997, 12(2): 277-

Radloff LS, Teri L: Use of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale with older adults. Clinical Gerontologist. 1986, 5 (1-2): 119-

Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Van Limbeek J, Braam AW, De Vries MZ, Van Tilburg W: Criterion validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D): results from a community-based sample of older subjects in The Netherlands. Psychol Med. 1997, 27(1): 231-235. 10.1017/S0033291796003510.

Beekman AT, van Limbeek J, Deeg DJ, Wouters L, van Tilburg W: [A screening tool for depression in the elderly in the general population: the usefulness of Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)]. [Article in Dutch] Tijdschr Gerontol Geriatr. 1994, 25(3): 95-103.

Furukawa T, Anraku K, Hiroe T, Takahashi K, Kitamura T, Hirai T, Takahashi K, Iida M: Screening for depression among first-visit psychiatric patients: comparison of different scoring methods for the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale using receiver operating characteristic analyses. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997, 51(2): 71-78.

Furukawa T, Hirai T, Kitamura T, Takahashi K: Application of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale among first-visit psychiatric patients: a new approach to improve its performance. J Affect Disord. 1997, 46(1): 1-13. 10.1016/S0165-0327(97)00079-7.

McCallum J, Mackinnon A, Simons L, Simons J: Measurement properties of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale: an Australian community study of aged persons. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1995, 50(3): S182-189.

Orme JG, Reis J, Herz EJ: Factorial and discriminant validity of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale. J Clin Psychol. 1986, 42(1): 28-33.

Soler J, Perez-Sola V, Puigdemont D, Perez-Blanco J, Figueres M, Alvarez E: [Validation study of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression of a Spanish population of patients with affective disorders].[Article in Spanish]. Actas Luso Esp Neurol Psiquiatr Cienc Afines. 1997, 25(4): 243-249.

Roberts RE: Reliability of the CES-D scale in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Research. 1980, 2: 125-134. 10.1016/0165-1781(80)90069-4.

Garcia M, Marks G: Depressive symptomatology among Mexican-American adults: an examination with the CES-D Scale. Psychiatry Research. 1989, 27: 137-10.1016/0165-1781(89)90129-7.

Golding JM, Aneshensel CS, Hough RL: Responses to Depression Scale items among Mexican-American and non-Hispanic whites. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1991, 47(1): 61-

Guarnaccia PJ, Angel R, Worobey JL: The factor structure of the CES-D in the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Sturvey: The inflluences of ethnicity, gender and language. Social Science & Medicine. 1989, 29(1): 85-10.1016/0277-9536(89)90131-7.

Liang J, Van Tran T, Krause N, Markides KS: Generational differences in the structure of the CES-D scale in Mexican Americans. Journal of Gerontology. 1989, 44(3): S110-

Vega W, Warheit G, Buhl-Auth J, Meinhardt K: The prevalence of depressive symptoms among Mexican Americans and Anglos. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1984, 120(4): 592-

Chan AC: Clinical validation of the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Chinese version. J Aging Health. 1996, 8(2): 238-253.

Chen IG, Roberts RE, Aday LA: Ethnicity and adolescent depression: the case of Chinese Americans. 1:. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998, 186(10): 623-630. 10.1097/00005053-199810000-00006.

Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen YR: Ethnocultural differences in prevalence of adolescent depression. 3:. Am J Community Psychol. 1997, 25(1): 95-110. 10.1023/A:1024649925737.

Fava GA: Assessing depressive symptoms across cultures: Italian validation of the CES-D self-rating scale. J Clin Psychol. 1983, 39(2): 249-251.

Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Roberts RE, Allen NB: Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) as a screening instrument for depression among community-residing older adults. Psychol Aging. 1997, 12(2): 277-287.

Iwata N, Roberts RE: Age differences among Japanese on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: an ethnocultural perspective on somatization. Soc Sci Med. 1996, 43(6): 967-974. 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00005-6.

Iwata N, Saito K, Roberts RE: Responses to a self-administered depression scale among younger adolescents in Japan. Psychiatry Res. 1994, 53(3): 275-287. 10.1016/0165-1781(94)90055-8.

Roberts RE: Manifestation of depressive symptoms among adolescents. A comparison of Mexican Americans with the majority and other minority populations. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1992, 180(10): 627-633.

Cynthia Mulrow, John Williams, Meghan Gerety, Gilbert Ramirez, Oscar Montiel, Caroline Kerber: Case-Finding Instruments for Depression in Primary Care Settings Annals of Internal Medicine,. 1992, 123: 913-921.

Simon GE, VonKorff M: Recognition, management, and outcomes of depression in primary care. Arch Fam Med. 1995, 4: 99-105. 10.1001/archfami.4.2.99.

Gerber PD, Barrett J, Barrett J, Manheimer E, Whiting R, Smith R: Recognition of depression by internists in primary care: a comparison of internist and gold standard psychiatric assessments. J Gen Intern Med. 1989, 4: 7-13.

Katon W, Roy-Byrne PP: Antidepressants in the medically ill: diagnosis and treatment in primary care. Clin Chem. 1988, 34: 829-36.

Schurman RA, Krooner PD, Mitchell JB: The hidden mental health network. Treatment of mental illness by nonpsychiatric physicians. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985, 42: 89-94.

Callahan CM, Hendrie HC, Dittus RS, Brater DC, Hui SL, Tierney WM: Improving treatment of late life depression in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994, 42: 840-5.

Brody DS, Lerman CE, Wolfson HG, Caputo GC: Improvement in physicians' counseling of patients with mental health problems. Arch Intern Med. 1990, 150: 993-8. 10.1001/archinte.150.5.993.

Magruder-Habib K, Zung WW, Feussner JR: Improving physicians' recognition and treatment of depression in general medical care. Med Care. 1990, 28: 239-50.

Rand EH, Badger LW, Coggins DR: Toward a resolution of contradictions. Utility of feedback from the GHQ. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1988, 10: 189-96. 10.1016/0163-8343(88)90018-7.

Rucker L, Frye EB, Cygan RW: Feasibility and usefulness of depression screening in medical outpatients. Arch Intern Med. 1986, 146: 729-31. 10.1001/archinte.146.4.729.

Hoeper EW, Nycz GR, Kessler LG, Burke JD, Pierce WE: The usefulness of screening for mental illness. Lancet. 1984, 1: 33-5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(84)90192-2.

Zung WW, King RE: Identification and treatment of masked depression in a general medical practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 1983, 44: 365-8.

Zung WW, Magill M, Moore JT, George DT: Recognition and treatment of depression in a family medicine practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 1983, 44: 3-6.

Johnstone A, Goldberg D: Psychiatric screening in general practice.A controlled trial. Lancet. 1976, 1: 605-8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(76)90415-3.

Magruder-Habib K, Zung WWK, Feussner JR: Improving physicians' recognition and treatment of depression in general medical care: results from a randomized clinical trial. Med Care. 1990, 28: 239-250.

Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination: Canadian guide to clinical preventive health care. Ottawa: Canada Communication Group,. 1994, : 450-455.

American Academy of Family Physicians: Age charts for periodic health examination. Kansas City, MO: American Academy of Family Physicians,. 1994

American Medical Association: Guidelines for adolescent preventive services (GAPS): recommendations and rationale. Chicago: American Medical Association,. 1994, : 131-139.

Roberts RE, Rhoades HM, Vernon SW: Using the CES-D scale to screen for depression and anxiety: effects of language and ethnic status. Psychiatry Res. 1990, 31(1): 69-83. 10.1016/0165-1781(90)90110-Q.

Roberts RE, Vernon SW, Rhoades HM: Effects of language and ethnic status on reliability and validity of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale with psychiatric patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989, 177(10): 581-592.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/content/backmatter/1471-244X-1-3-b1.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Fountoulakis, K., Iacovides, A., Kleanthous, S. et al. Reliability, Validity and Psychometric Properties of the Greek Translation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) Scale. BMC Psychiatry 1, 3 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-1-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-1-3