Abstract

Background

Observational studies have consistently shown that aspirin and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use is associated with a close to 50% reduced risk of colorectal cancer. Studies assessing the effects of NSAIDs on other cancers have shown conflicting results. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate the relationship between NSAID use and cancer other than colorectal.

Methods

We performed a search in Medline (from 1966 to 2002) and identified a total of 47 articles (13 cohort and 34 case-control studies). Overall estimates of the relative risk (RR) were calculated for each cancer site using random effects models.

Results

Aspirin use was associated with a reduced risk of cancer of the esophagus and the stomach (RR, 0.51; 95%CI (0.38–0.69), and 0.73; 95%CI (0.63–0.84)). Use of NSAIDs was similarly associated with a lower risk of esophageal and gastric cancers (RR,0.65; 95% CI(0.46–0.92) and RR,0.54; 95%CI (0.39–0.75)). Among other cancers, only the results obtained for breast cancer were fairly consistent in showing a slight reduced risk among NSAID and aspirin users (RR, 0.77; 95%CI (0.66–0.88), and RR, 0.77; 95%CI (0.69–0.86) respectively)).

Conclusions

The results of this meta-analysis show that the potential chemopreventive role of NSAIDs in colorectal cancer might be extended to other gastrointestinal cancers such as esophagus and stomach. Further research is required to evaluate the role of NSAIDs at other cancers sites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

People who have regularly taken aspirin or other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are at a reduced risk of developing or dying from colorectal cancer [1–3]. The association with other types of cancer remains unclear. Animal studies have shown a protective effect of these drugs in colon [4], esophagus [5], stomach [6, 7], pancreas [8], breast [9, 10], prostate [11], lung [12], and bladder cancer [13], suggesting a common mechanistic effect of NSAIDs in all these different cancers.

NSAIDs could reduce the risk of cancer through the inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) [14], the enzyme that is responsible for the production of various prostaglandins. Prostaglandins play a key role on the accelerated proliferation of tumor tissue. Furthermore there is mounting evidence that NSAIDs may have the ability to restore apoptosis and inhibit angiogenesis [15].

If this proposed protective mechanism of NSAIDs is valid, the preventive effect of NSAIDs could extend to other human cancers. To date, epidemiological studies in cancer other than colorectal are scarce and offer inconsistent results.

The primary aim of our analysis is the use of meta-analytical techniques to evaluate the effect of aspirin and non-aspirin NSAIDs (NA-NSAIDs) on cancer sites other than the colon and rectum. We present summary estimates for the effect of these drugs in cancer sites where at least two epidemiological studies could be found.

Methods

Our search included original articles indexed in Medline from January 1966 to December 2002. We searched for different common terms used to refer to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs ("NSAIDs", "anti-inflammatory drugs") or specific drug names such as "aspirin". Similarly we used different terms referring to cancer ("neoplasm", "malignancies", and the prefix "carcino-"). Additionally we included references cited in original or review articles that were not included in our original list. We restricted our search to studies performed in humans and published in English or Spanish. We individually reviewed all the abstracts and obtained those articles that satisfied our inclusion criteria: cohort or case-control studies studying the association between NSAIDs and cancer other than colorectal, and reporting an estimate of association such as relative risk (RR) with confidence intervals or enough information to compute it. Forty-nine articles were considered to meet our inclusion criteria. After review by two of the authors, two of these articles were excluded. The reasons for exclusion were absence of a control group [16], invalid exposure and outcome ascertainment [17]. A total of forty-seven eligible studies were finally identified.

Two of the authors participated in the data extraction process using a standardized form. Data regarding study design, analyses and results were entered into a database. The fields extracted included study design, year of publication, country, matching used, percentage of response, exposure assessment, exposure definition, lag time between exposure and outcome, prevalence of exposure, outcome assessment, and RR with 95% confidence intervals (CI). We assumed that the odds ratio (OR) from case-control studies provided a valid estimate for the RR. The exposures of interest consisted of aspirin, and non-aspirin NSAIDs (NA-NSAIDs). In this study, the term NSAIDs refers to either aspirin and/or NA-NSAIDs. Some studies included paracetamol in the NSAID and/or NA-NSAID groups. Most studies reported a definition of regular use (n = 34) and whenever available the estimate for this exposure was the one extracted. When no clear definition of regular use was provided (n = 13), we extracted the most mechanistically meaningful estimate after reaching consensus between authors in all instances. A total of nine studies reporting estimates for multiple endpoints contributed to more than one cancer site. We explored all nine cancer sites for which two or more eligible studies were found. In the case of cancer of the esophagus we focused on adenocarcinoma when more than one histological type was studied.

We fit a DerSimonian and Laird random effects model [18] to obtain overall estimates for the effects of aspirin, NA-NSAIDs and NSAIDs in each specific cancer site using STATA software. This model is more robust than the fixed effects model and incorporates into the weighting scheme both the within-study and among-study variance. Heterogeneity was explored using Q test statistic [18] in sets where three or more studies were available. When the result from this test reached statistical significance we further assessed to what extent different study characteristics could explain the heterogeneity with meta-regression. We explored potential publication bias qualitatively and quantitatively using funnel plots and kendall's tau rank correlation tests [19].

Results

Studies characteristics

Among the 47 studies analyzed [20–66], 13 were cohort and 34 were case-control studies. Seventeen of the case-control studies were population based (either nested in a cohort or using methods like random digit dialing to ensure that controls are a sample of the underlying cohort that gave rise to the cases)[21, 22, 24, 27, 28, 30, 36, 39, 44, 54, 59–61, 63–66] whereas the other seventeen were hospital based (using non-cancer hospital controls) [23, 26, 32–35, 37, 38, 42, 45, 47–49, 51, 53, 55, 56, 62]. Regarding exposure assessment, most studies (n = 22) used personal interview typically performed by trained personnel [22, 24–26, 28, 30–34, 38, 41–43, 45, 47, 51, 56, 60, 63, 65, 66]. Thirteen studies used mailed questionnaires [21, 23, 27, 29, 39, 40, 46, 50, 52, 54, 56, 58, 64] and six used in-hospital questionnaires [35, 37, 48, 49, 53, 55]. The rest used either automated databases (n = 4)[20, 36, 44, 61] or medical records (n = 2) [59, 62]. Exposure definition was very heterogeneous across the different studies and attempts to categorize it in a few groups for further analysis were unsuccessful. It ranged from more than 6 tablets per day to ever use of NSAIDs in the 30 days prior to start date. Prevalence of exposure among controls or cohort members ranged from 4 to 42 percent for NSAIDs (median, 8 percent), from 2 to 64 percent for aspirin (median, 16 percent), and from 3 to 46 percent for NA-NSAIDs (median, 12 percent).

Some studies incorporated the concept of lag time into their exposure definition (time period before the index date that was discounted for assessing the exposure status). This is mainly motivated by the belief that early symptoms of the disease (cancer in this case) in the sub-clinical phase (latent period) might induce or contra-indicate the use of NSAIDs (protopathic bias) [44, 67]. Nine studies used a lag time of 1 year, one study used 1 year and a half, and two studies used 2 years.

All but ten case-control studies used matched designs (frequency matched (n = 12) or individually matched (n = 12)). Among the individually matched seven studies considered the matching in the analysis and five did not. All studies used newly diagnosed cancer as the primary endpoint except for studies by Thun et al and Suleiman et al that used fatal cancer as outcome.

Most studies were published after 1997 (n = 33). The rest were published in 1996 (n = 3), 1995 (n = 4), 1994 (n = 1), 1993 (n = 2), 1989 (n = 1), 1988 (n = 1), 1985 (n = 1) and 1980 (n = 1). The majority of the studies were conducted in North America (USA (n = 32) or Canada (n = 2)). Ten studies were conducted in Europe (U.K. (n = 4), Greece (n = 2), France (n = 1), Italy (n = 1), Russia (n = 1), and Sweden (n = 1)), one study in Australia and one study in New Zealand. Additionally, there was one multicentered international study.

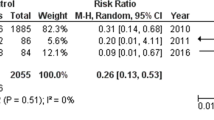

Tables 1 through 9 show the exposure definition, exposure assessment, study type, and the estimates of association for each individual study according to the cancer site. Table 10 summarizes the results by type of drug and cancer site. The pooled RR estimates for esophagus and stomach showed a significant protective effect of NSAIDs in the range of a 40 percent reduction. Aspirin but not NA-NSAIDs appeared to be associated with a reduced pancreas cancer incidence around 30 percent (although this result was not significant). Breast cancer was the only other site where results were rather consistent in showing a protection ranging around a 20 percent reduction. Results obtained for other studied cancer sites, i.e. ovary, prostate, bladder, and lung were compatible with no effect or a possibly slight reduced risk. The result for kidney cancer is compatible with no effect or possibly a slight increased risk.

Studies assessing the effect of aspirin and other NSAIDs on cancer of the esophagus were consistent in finding a protective effect regardless of the study design or exposure assessment. Among the eight studies identified none yielded a point estimate larger than 0.85 independently of the exposure category (see table 1). All but one of the individual estimates of the effect of aspirin and other NSAIDs on the risk of developing gastric cancer were smaller than one. Among the five studies evaluating the effect of aspirin on the risk of gastric cancer, all of them showed a protective effect. In three out of these five studies confidence intervals did not include the null.

We found a significant amount of heterogeneity for NSAIDs in two of the cancer sites, breast and prostate, for aspirin in renal cancer, and for aspirin and NSAIDs in lung cancer. Nine studies provided data on the association between NSAID use and breast cancer incidence. The overall estimate for this effect was 0.77 (95% CI, 0.66–0.88) and significant between-study variation was found. Study design (hospital based case-control, population based case-control, or cohort study) and exposure assessment appeared to be the variables that explained heterogeneity to a greater extent in the meta-regression. The pooled estimate for hospital based case-control studies (n = 4) was 0.69 (95%CI,0.62–0.77) whereas the pooled estimate for population based case-control studies (n = 4) was 0.89 (95% CI, 0.74–1.08). There was only one cohort study (RR, 0.57;95%CI,0.44–1.73). Regarding exposure assessment, only two studies used mailed questionnaires to ascertain NSAID exposure. The combined estimate for these studies was 0.67 (95%CI, 0.51–0.89). For studies using personal interview as exposure assessment method (n = 4) the overall estimate was similar (RR,0.69; 95%CI,0.62–0.77). The other three studies used automated databases to elicit exposure and they found little or no effect (RR,0.95;95%CI,0.77–1.16). Once we adjusted for exposure assessment, study design did not explain additional heterogeneity. We found that the protective effect of NSAID use was slightly stronger among studies not using lag time (n = 3) (RR,0.69;95%CI,0.51–0.94) than among those using lag time (n = 5) (RR, 0.81; 95%CI,0.69–0.96). It is somewhat difficult to draw conclusions about possible sources of heterogeneity in the other two cases (prostate, kidney and lung) due to the limited number of studies.

Discussion

This meta-analysis attempts to evaluate the effectiveness of NSAIDs in reducing the risk of cancer other than colorectal as primary prevention. Based on a limited number of studies, the results show that NSAIDs overall and aspirin in particular are associated with a decreased risk of developing both esophageal cancer and gastric cancer with a magnitude of effect (40 % reduction) comparable to the one observed with colorectal cancer. A recently published meta-analysis addressing esophageal cancer found similar results [68]. The results for breast are consistent in showing a slight protection. Overall results for the effect of aspirin on pancreatic cancer show a non-significant risk reduction, while results from ovary, prostate, kidney, bladder and lung cancer are compatible with no effect of NSAIDs in preventing these cancers.

The association with NSAIDs has been extensively studied for colorectal cancer through observational methods and it is now pending confirmation on the results of experimental studies currently ongoing for secondary prevention [69]. If the observed association in colorectal cancer were true, one could expect a similar effect in other cancers of the gastrointestinal tract. The consistency observed in the results for esophageal and gastric cancer in our meta-analysis tends to support this hypothesis. Unfortunately, very few studies assessed whether contraindication for use of aspirin and NA-NSAIDs could explain the observed protective effect. It is most likely true that patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms or disease are likely to use less NSAIDs than the general population, and these conditions are positively correlated with the occurrence of both esophageal and gastric cancer.

Overall results for the effect of aspirin on pancreatic cancer show a non-significant risk reduction around 30%. While the two cohort studies show a strong protective effect (close to 50% reduction)[23, 43] a recently published case-control study shows no effect [49].

The results for breast are consistent in showing a slight protection (around 20%). However, as we previously indicated, results from other sites (ovary, prostate, kidney, bladder and lung cancer) are compatible with no effect of NSAIDs in preventing these cancers. This seems to confirm the idea that NSAID primary prophylaxis for cancer, far from being the new panacea, has limited results and restricted to some cancers mainly in the gastrointestinal area[70, 71] although evidence for other cancers is sparse and would require additional studies to have a more robust estimate of the true association.

Phenacetin-containing analgesics have been shown to increase renal cancer [72], and it is unclear whether this effect is common to NSAIDs. Our result on cancer of the kidney cannot exclude a slight increased risk associated with aspirin use. However caution must be taken when interpreting these results. Phenacetin was commonly used in combination with aspirin, so the studied effect of aspirin often combines the effect of aspirin and phenacetin given together [73]. The results for prostate cancer are not compatible with an increased risk of NSAIDs, which seems to support the hypothesis that the elevated risk observed in some studies might result from detection bias.

In table 10 the estimate for the overall effect of NSAIDs on gastric cancer is not the weighted average of the corresponding estimates of aspirin and NA-NSAIDs. This is due to the fact that none of the studies assessed simultaneously the three different types of drug exposure and therefore estimates for each type of NSAID arise from different studies with different characteristics.

Tests for heterogeneity found a significant amount of between-study variance in four of the combined estimates. One problem with these tests is that they are not sensitive enough when a small number of studies is being pooled. Consequently, caution must be taken when interpreting these results. However, the use of a random effects model takes into account to certain extent this additional source of variability and incorporates it in obtaining the pooled estimate. Our analysis found significant heterogeneity among the studies addressing the association between NSAIDs and breast cancer. Further analysis of this variation showed that among case-control studies, hospital based studies yielded a more optimistic result than population-based. Two key features that define the quality of a case-control study are the selection of controls and the way in which the exposure is ascertained. Controls in hospital-based studies rarely attain to be a true representative sample from the source population where cases have arisen. This is especially troublesome when the reason for admission could be related to the exposure, which represents the greatest limitation of this study design [74]. On the other hand, controls in population-based studies tend to give a more valid estimate of the exposure in the source population. The method used to elicit the exposure will also determine the quality of the data. Automated databases (AD) offer some advantages when long term drug exposure is to be ascertained. In contrast to personal interviews or self-administered questionnaires that rely heavily on the subject's ability to recall, AD provide detailed information on dates of use and type of drugs used. Furthermore this information is equally good for cases or controls irrespective of the event of interest since it was recorded prospectively (as opposed to methods based on subject's ability to recall which may depend on the case status). We found that the estimate for the subset of studies using AD was more conservative than the estimates for studies using personal interviews or mailed questionnaires. On the other hand, the downside of using ADs in assessing NSAID exposure is its inability to capture exposure to widely available over-the-counter NSAIDs. This could result in non-differential misclassification of exposure that would dilute the underlying effect, and represents an alternative explanation for the more conservative results obtained in the AD subset.

One possible explanation of RR heterogeneity is variation in background rate. This ought to be addressed by considering the background rates in study populations exhibiting heterogeneity. However, most of the population based case-control studies did not report incidence rates (or enough information to compute) and there were a limited number of cohort studies. Therefore we were unable to assess the influence of different background rates.

The limited number of studies involved in the estimates for the effects of aspirin on lung cancer and NSAIDs on prostate cancer prevents us from a conclusive analysis of the source of heterogeneity observed in these estimates.

Exposure definition in all the reviewed studies was quite heterogeneous. According to the proposed mechanism, chronic exposure to NSAIDs would be needed in order to observe the hypothesized protective effect. However, we found that studies using relatively broad exposure definitions (such as "ever use of aspirin in the 30 days prior to start date") were able to detect associations similar to the ones observed in studies with more specific and "valid" exposure definitions. In general, the consistency in the results was surprisingly high considering the large amount of heterogeneity in exposure definition across studies. In our opinion, this is due to the fact that, in these populations, different exposure definitions are still highly correlated (i.e. subjects classified as exposed by "loose" exposure definitions have still a relatively high probability of being chronic users as compared to the ones called non users). This, somehow, justifies pooling these studies to obtain an overall estimate. However, this correlation between different exposure definitions will be different between aspirin and NA-NSAIDs. Since the relative prevalence of chronic use is greater among aspirin users (as a result of its predominant use for prevention of cardiovascular disease) than among NA-NSAID users, this grouping of exposure would result in a greater misclassification among NA-NSAID users than aspirin users. This might partly explain the closer to the null results obtained for NA-NSAIDs though the number of individual studies were too limited to analyze this with confidence. Overall prevalence of NSAID exposure among the controls/cohort was quite variable across studies. Based on a qualitative review, we could say that it was a function of both the nature of the study population and the looseness of the exposure definition applied. It is noteworthy that studies that reported abnormally low or high prevalence of exposure (inversely related to studies using AD) tended to find extreme results in both directions.

Protopathic bias could overestimate exposure among cases in those studies that do not include lag time in their exposure definition if early symptoms of cancer influenced the subsequent use of NSAIDs. Our analysis did not identify large differences between studies using and not using lag time although the latter generally yielded more conservative results. Also, since the primary endpoint in most of these studies was clinical diagnosis of cancer, and given that this endpoint can be associated with screening frequency, this potential bias deserves consideration. This is especially true for cancers such as breast or prostate where screening methods are widely available. Barry hypothesized that if NSAID use is a proxy for poorer general health, one would expect these people to get less screening and therefore to be less likely to be diagnosed with cancer [75], but the exact opposite argument can be made with equal force. At present, most chronic NSAID use comes from low dose aspirin indicated for cardioprotection, and people pursuing this prophylactic measure are likely to be more health-conscious and follow other preventive actions such as timely screening. This would associate NSAID exposure spuriously with a higher risk of cancer. Therefore, the net effect of this potential bias, if any, is difficult to predict.

Some authors have questioned the use of random effect models arguing that it might not always be more conservative than the fixed effects model [76]. The use of fixed effects models in our data resulted in very similar point estimates and full consistency regarding statistical significance (data not shown). We evaluated the potential for publication bias plotting the log RR from each study against its standard error as well as using kendall's tau test and found no substantial evidence of publication bias.

Conclusions

In summary, the results of this meta-analysis show that the potential chemopreventive role of NSAIDs in colorectal cancer might extend to other gastrointestinal cancers such as esophagus and stomach. There is evidence that supports a similar effect, though to a smaller extent, of NSAIDs in breast cancer whereas such potential in other cancers appears to be slim based on the reviewed literature. In general, the extent to which this potential benefit might be offset by the adverse effects of long-term use of these drugs is not clear especially in cancers with low incidence and clearly needs to be taken into account when evaluating the chemoprophylactic role of NSAIDs. The role of a new class of NSAIDs such as selective COX-2 inhibitors is yet to be assessed as well as the optimal dose and duration regimen for a hypothetical prevention therapy. Further research is required to solve all these open and important questions.

References

Thun MJ, Namboodiri MM, Heath CW: Aspirin use and reduced risk of fatal colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 1991, 325 (23): 1593-6.

Giovannucci E, Egan KM, Hunter DJ, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Speizer FE: Aspirin and the risk of colorectal cancer in women. N Engl J Med. 1995, 333 (10): 609-14. 10.1056/NEJM199509073331001.

García Rodríguez LA, Huerta-Alvarez C: Reduced incidence of colorectal adenoma among long-term users of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs: a pooled analysis of published studies and a new population-based study. Epidemiology. 2000, 11 (4): 376-81. 10.1097/00001648-200007000-00003.

Pollard M, Luckert PH: Prolonged antitumor effect of indomethacin on autochthonous intestinal tumors in rats. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1983, 70 (6): 1103-5.

Li M, Lotan R, Levin B, Tahara E, Lippman SM, Xu XC: Aspirin induction of apoptosis in esophageal cancer: a potential for chemoprevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000, 9 (6): 545-9.

Lehnert T, Deschner EE, Karmali RA, DeCosse JJ: Effect of flurbiprofen and 16,16-dimethyl-prostaglandin E2 on gastrointestinal tumorigenesis induced by N-methyl-N'-nitro-N-nitrosoguanidine in rats. I. Squamous epithelium and mesenchymal tissue. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987, 78 (5): 923-9.

Shibata MA, Hirose M, Masuda A, Kato T, Mutai M, Ito N: Modification of BHA forestomach carcinogenesis in rats: inhibition by diethylmaleate or indomethacin and enhancement by a retinoid. Carcinogenesis. 1993, 14 (7): 1265-9.

Takahashi M, Furukawa F, Toyoda K, Sato H, Hasegawa R, Imaida K, Hayashi Y: Effects of various prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors on pancreatic carcinogenesis in hamsters after initiation with N-nitrosobis(2-oxopropyl)amine. Carcinogenesis. 1990, 11 (3): 393-5.

Lala PK, Al-Mutter N, Orucevic A: Effects of chronic indomethacin therapy on the development and progression of spontaneous mammary tumors in C3H/HEJ mice. Int J Cancer. 1997, 73 (3): 371-80. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19971104)73:3<371::AID-IJC12>3.0.CO;2-G.

Robertson FM, Parrett ML, Joarder FS, Ross M, Abou-Issa HM, Alshafie G, Harris RE: Ibuprofen-induced inhibition of cyclooxygenase isoform gene expression and regression of rat mammary carcinomas. Cancer Lett. 1998, 122 (1–2): 165-75. 10.1016/S0304-3835(97)00387-X.

Liu XH, Kirschenbaum A, Yao S, Lee R, Holland JF, Levine AC: Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 suppresses angiogenesis and the growth of prostate cancer in vivo. J Urol. 2000, 164: 820-5. 10.1097/00005392-200009010-00056.

Jalbert G, Castonguay A: Effects of NSAIDs on NNK-induced pulmonary and gastric tumorigenesis in A/J mice. Cancer Lett. 1992, 66 (1): 21-8.

Cohen SM, Zenser TV, Murasaki G, Fukushima S, Mattammal MB, Rapp NS, Davis BB: Aspirin inhibition of N-[4-(5-nitro-2-furyl)-2-thiazolyl]formamide-induced lesions of the urinary bladder correlated with inhibition of metabolism by bladder prostaglandin endoperoxide synthetase. Cancer Res. 1981, 41 (9): 3355-9.

Sjodahl R: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and the gastrointestinal tract. Extent, mode, and dose dependence of anticancer effects. Am J Med. 2001, 110 (1A): 66S-69S. 10.1016/S0002-9343(00)00646-X.

Thun MJ, Henley SJ, Patrono C: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as anticancer agents: mechanistic, pharmacologic, and clinical issues. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002, 94 (4): 252-66. 10.1093/jnci/94.4.252.

Gridley G, McLaughlin JK, Ekbom A, Klareskog L, Adami HO, Hacker DG, Hoover R, Fraumeni JF: Incidence of cancer among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993, 85 (4): 307-11.

Bucher C, Jordan P, Nickeleit V, Torhorst J, Mihatsch MJ: Relative risk of malignant tumors in analgesic abusers: effects of long-term intake of aspirin. Clin Nephrol. 1999, 51: 67-72.

DerSimonian R, Laird N: Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986, 7: 177-188. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2.

Begg CB, Mazumdar M: Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994, 50 (4): 1088-101.

Friedman GD, Ury HK: Initial screening for carcinogenicity of commonly used drugs. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1980, 65 (4): 723-33.

Akhmedkhanov A, Toniolo P, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Kato I, Koenig KL, Shore RE: Aspirin and epithelial ovarian cancer. Preventive Medicine. 2001, 33 (6): 682-7. 10.1006/pmed.2001.0945.

Akre K, Ekstrom AM, Signorello LB, Hansson LE, Nyren O: Aspirin and risk for gastric cancer: a population-based case-control study in Sweden. British Journal of Cancer. 2001, 84 (7): 965-8. 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1702.

Anderson KE, Johnson TW, Lazovich D, Folsom AR: Association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and the incidence of pancreatic cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002, 94 (15): 1168-71. 10.1093/jnci/94.15.1168.

Castelao JE, Yuan JM, Gago-Dominguez M, Yu MC, Ross RK: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and bladder cancer prevention. British Journal of Cancer. 2000, 82 (7): 1364-9. 10.1054/bjoc.1999.1106.

Coogan PF, Rao SR, Rosenberg L, Palmer JR, Strom BL, Zauber AG, Stolley PD, Shapiro S: The relationship of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use to the risk of breast cancer. Preventive Medicine. 1999, 29 (2): 72-6. 10.1006/pmed.1999.0518.

Coogan PF, Rosenberg L, Palmer JR, Strom BL, Zauber AG, Stolley PD, Shapiro S: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of digestive cancers at sites other than the large bowel. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000, 9 (1): 119-23.

Cotterchio M, Kreiger N, Sloan M, Steingart A: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and breast cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001, 10 (11): 1213-7.

Cramer DW, Harlow BL, Titus-Ernstoff L, Bohlke K, Welch WR, Greenberg ER: Over-the-counter analgesics and risk of ovarian cancer. Lancet. 1998, 351: 104-107. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)08064-1.

Egan KM, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci E, Rosner BA, Colditz GA: Prospective study of regular aspirin use and the risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996, 88 (14): 988-93.

Farrow DC, Vaughan TL, Hansten PD, Stanford JL, Risch HA, Gammon MD, Chow WH, Dubrow R, Ahsan H, Mayne ST, Schoenberg JB, West AB, Rotterdam H, Fraumeni JF, Blot WJ: Use of aspirin and other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of esophageal and gastric cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998, 7 (2): 97-102.

Funkhouser EM, Sharp GB: Aspirin and reduced risk of esophageal carcinoma. Cancer. 1995, 76 (7): 1116-9.

Garidou A, Tzonou A, Lipworth L, Signorello LB, Kalapothaki V, Trichopoulos D: Life-style factors and medical conditions in relation to esophageal cancer by histologic type in a low-risk population. Int J Cancer. 1996, 68 (3): 295-9. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19961104)68:3<295::AID-IJC5>3.0.CO;2-X.

Harris RE, Namboodiri K, Stellman SD, Wynder EL: Breast cancer and NSAID use: Heterogeneity of effect in a case-control study. Prev Med. 1995, 24: 119-20. 10.1006/pmed.1995.1022.

Harris RE, Namboodiri KK, Farrar WB: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and breast cancer. Epidemiology. 1996, 7: 203-5.

Harris RE, Kasbari S, Farrar WB: Prospective study of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and breast cancer. Oncol Rep. 1999, 6 (1): 71-3.

Langman MJ, Cheng KK, Gilman EA, Lancashire RJ: Effect of anti-inflammatory drugs on overall risk of common cancer: case-control study in general practice research database. Br Med J. 2000, 320 (7250): 1642-6. 10.1136/bmj.320.7250.1642.

Moysich KB, Mettlin C, Piver MS, Natarajan N, Menezes RJ, Swede H: Regular use of analgesic drugs and ovarian cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001, 10 (8): 903-6.

Nelson JE, Harris RE: Inverse association of prostate cancer and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs): results of a case-control study. Oncology Reports. 2000, 7 (1): 169-70.

Norrish AE, Jackson RT, McRae CU: Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and prostate cancer progression. Int J Cancer. 1998, 77 (4): 511-5. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19980812)77:4<511::AID-IJC6>3.3.CO;2-T.

Paganini-Hill A, Chao A, Ross RK, Henderson BE: Aspirin use and chronic diseases: A cohort study of the elderly. Br Med J. 1989, 299: 1247-50.

Roberts RO, Jacobson DJ, Girman CJ, Rhodes T, Lieber MM, Jacobsen SJ: A population-based study of daily nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and prostate cancer. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002, 77 (3): 219-25.

Rosenberg L, Palmer JR, Rao RS, Coogan PF, Strom BL, Zauber AG, Stolley PD, Shapiro S: A case-control study of analgesic use and ovarian cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000, 9: 933-7.

Schreinemachers DM, Everson RB: Aspirin use and lung, colon, and breast cancer incidence in a prospective study. Epidemiology. 1994, 5 (2): 138-46.

Sharpe CR, Collet JP, McNutt M, Belzile E, Boivin JF, Hanley JA: Nested case-control study of the effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on breast cancer risk and stage. British Journal of Cancer. 2000, 83 (1): 112-20. 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1119.

Tavani A, Gallus S, La Vecchia C, Conti E, Montella M, Franceschi S: Aspirin and ovarian cancer: an Italian case-control study. Annals of Oncology. 2000, 11 (9): 1171-3. 10.1023/A:1008373616424.

Thun MJ, Namboodiri MM, Calle EE, Flanders WD, Heath CW: Aspirin use and risk of fatal cancer. Cancer Research. 1993, 53 (6): 1322-7.

Tzonou A, Polychronopoulou A, Hsieh CC, Rebelakos A, Karakatsani A, Trichopoulos D: Hair dyes, analgesics, tranquilizers and perineal talc application as risk factors for ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 1993, 55: 408-10.

Zaridze D, Borisova E, Maximovitch D, Chkhikvadze V: Aspirin protects against gastric cancer: results of a case-control study from Moscow, Russia. Int J Cancer. 1999, 82 (4): 473-6. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990812)82:4<473::AID-IJC1>3.0.CO;2-K.

Menezes RJ, Huber KR, Mahoney MC, Moysich KB: Regular use of aspirin and pancreatic cancer risk. BMC Public Health. 2002, 2 (1): 18-10.1186/1471-2458-2-18.

Fairfield KM, Hunter DJ, Fuchs CS, Colditz GA, Hankinson SE: Aspirin, other NSAIDs, and ovarian cancer risk (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2002, 13 (6): 535-42. 10.1023/A:1016380917625.

Harris RE, Beebe-Donk J, Schuller HM: Chemoprevention of lung cancer by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs among cigarette smokers. Oncol Rep. 2002, 9 (4): 693-5.

Leitzmann MF, Stampfer MJ, Ma J, Chan JM, Colditz GA, Willett WC, Giovannucci E: Aspirin use in relation to risk of prostate cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002, 11 (10): 1108-11.

Irani J, Ravery V, Pariente JL, Chartier-Kastler E, Lechevallier E, Soulie M, Chautard D, Coloby P, Fontaine E, Bladou F, Desgrandchamps F, Haillot O: Effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents and finasteride on prostate cancer risk. J Urol. 2002, 168 (5): 1985-8.

Akhmedkhanov A, Toniolo P, Zeleniuch-Jacquotte A, Koenig KL, Shore RE: Aspirin and lung cancer in women. Br J Cancer. 2002, 87 (1): 49-53. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600370.

Moysich KB, Menezes RJ, Ronsani A, Swede H, Reid ME, Cummings KM, Falkner KL, Loewen GM, Bepler G: Regular aspirin use and lung cancer risk. BMC Cancer. 2002, 2 (1): 31-10.1186/1471-2407-2-31.

Rosenberg L: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cancer. Prev Med. 1995, 24 (2): 107-9. 10.1006/pmed.1995.1018.

Habel LA, Zhao W, Stanford JL: Daily aspirin use and prostate cancer risk in a large, multiracial cohort in the US. Cancer Causes Control. 2002, 13 (5): 427-34. 10.1023/A:1015788502099.

Johnson TW, Anderson KE, Lazovich D, Folsom AR: Association of Aspirin and Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drug Use with Breast Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002, 11 (12): 1586-91.

Suleiman UL, Harrison M, Britton A, McPherson K, Bates T: H2-receptor antagonists may increase the risk of cardio-oesophageal adenocarcinoma: a case-control study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2000, 9 (3): 185-91. 10.1097/00008469-200006000-00007.

Cheng KK, Sharp L, McKinney PA, Logan RF, Chilvers CE, Cook-Mozaffari P, Ahmed A, Day NE: A case-control study of oesophageal adenocarcinoma in women: a preventable disease. Br J Cancer. 2000, 83 (1): 127-32. 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1121.

Meier CR, Schmitz S, Jick H: Association between acetaminophen or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and risk of developing ovarian, breast, or colon cancer. Pharmacotherapy. 2002, 22 (3): 303-9.

Neugut AI, Rosenberg DJ, Ahsan H, Jacobson JS, Wahid N, Hagan M, Rahman MI, Khan ZR, Chen L, Pablos-Mendez A, Shea S: Association between coronary heart disease and cancers of the breast, prostate, and colon. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998, 7 (10): 869-73.

McLaughlin JK, Blot WJ, Mehl ES, Fraumeni JF: Relation of analgesic use to renal cancer: population-based findings. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1985, 69: 217-22.

McCredie M, Ford JM, Stewart JH: Risk factors for cancer of the renal parenchyma. Int J Cancer. 1988, 42 (1): 13-6.

McCredie M, Pommer W, McLaughlin JK, Stewart JH, Lindblad P, Mandel JS, Mellemgaard A, Schlehofer B, Niwa S: International renal-cell cancer study. II. Analgesics. Int J Cancer. 1995, 60 (3): 345-9.

Gago-Dominguez M, Yuan JM, Castelao JE, Ross RK, Yu MC: Regular use of analgesics is a risk factor for renal cell carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 1999, 81 (3): 542-8. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690728.

Horwitz RI, Feinstein AR: The problem of "protopathic bias" in case-control studies. Am J Med. 1980, 68 (2): 255-8.

Corley DA, Kerlikowske K, Verma R, Buffler P: Protective association of aspirin/NSAIDs and esophageal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2003, 124 (1): 47-56. 10.1053/gast.2003.50008.

Anderson WF, Umar A, Viner JL, Hawk ET: The role of cyclooxygenase inhibitors in cancer prevention. Curr Pharm Des. 2002, 8 (12): 1035-62.

Baron JA, Sandler RS: Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and cancer prevention. Annu Rev Med. 2000, 51: 511-23. 10.1146/annurev.med.51.1.511.

Shaheen NJ, Straus WL, Sandler RS: Chemoprevention of gastrointestinal malignancies with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. Cancer. 2002, 94 (4): 950-63. 10.1002/cncr.10333.abs.

McLaughlin JK, Lipworth L: Epidemiologic aspects of renal cell cancer. Semin Oncol. 2000, 27 (2): 115-23.

McCredie M, Stewart JH, Day NE: Different roles for phenacetin and paracetamol in cancer of the kidney and renal pelvis. Int J Cancer. 1993, 53 (2): 245-9.

Feinstein AR, Walter SD, Horwitz RI: An analysis of Berkson's bias in case-control studies. J Chronic Dis. 1986, 39 (7): 495-504.

Barry MJ: NSAIDs and a lower risk of prostate cancer: causation or confounding?. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002, 77 (3): 217-8.

Poole C, Greenland S: Random-effects meta-analyses are not always conservative. American Journal of Epidemiology. 1999, 150: 469-475.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2407/3/28/prepub

Acknowledgements

We thank Jesper Lagergren and Alec Walker for their helpful comments on the manuscript.

Financial Support: AGP has been supported by grants from Fulbright-FIS, Real Colegio Complutense, and Harvard School of Public Health Pharmacoepidemiology Teaching and Research Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

None declared.

Authors' contributions

LAGR had the original idea, and contributed to the analysis and the report. RLR contributed to the literature search and review. AGP contributed to the literature review, the analysis and the report. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

González-Pérez, A., García Rodríguez, L.A. & López-Ridaura, R. Effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on cancer sites other than the colon and rectum: a meta-analysis. BMC Cancer 3, 28 (2003). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-3-28

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-3-28