Abstract

Background

There is very small occurrence of adenocarcinoma in the small bowel. We present a case of primary duodenal adenocarcinoma and discuss the findings of the case diagnostic modalities, current knowledge on the molecular biology behind small bowel neoplasms and treatment options.

Case

The patient had a history of iron deficiency anemia and occult bleeding with extensive workup consisting of upper endoscopy, colonoscopy, capsule endoscopy, upper gastrointestinal series with small bowel follow through and push enteroscopy. Due to persistent abdominal pain and iron deficiency anemia the patient underwent push enteroscopy which revealed adenocarcinoma of the duodenum. The patient underwent en-bloc duodenectomy which revealed T3N1M0 adenocarcinoma of the 4th portion of the duodenum.

Conclusions

Primary duodenal carcinoma, although rare should be considered in the differential diagnosis of occult gastrointestinal bleeding when evaluation of the lower and upper GI tract is unremarkable. We discuss the current evaluation and management of this small bowel neoplasm.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malignancies of the small intestine are uncommon, accounting for only roughly 1-2 % of malignant gastrointestinal (GI) diseases [1]. When compared to other cancer diagnosis rates, small bowel cancers average roughly 6000 per year in the United States [2]. As suggested by two recent major epidemiological studies on patients with small bowel neoplasms (SBN) identified from the National Cancer Data Base (NCDB, 1985-2005) and the Surveillance Epidemiology End Results (SEER, 1973-2004) database [3] as well as the Connecticut Tumor Registry [4], over the past twenty years, carcinoid tumors have become the most common SBN followed by adenocarcinomas (AC). A significant observation based on these studies is that from 1973 to 2004, the incidence of carcinoid tumors increased more than 4-fold (2.1 to 9.3 per million), with similar increases in the incidence of AC, stromal tumors, and lymphomas [3]. While AC is the most common malignancy of the duodenum the most common site of SBN is the ileum (Table 1), with a preponderance of lymphoma and carcinoids [5]. Among patients with Crohn's disease AC is most noted in ileum rather than the more proximal small bowel [6]. AC of the 3rd and 4th portions of the duodenum is very uncommon [7], and only 45% of duodenal carcinomas occur in that region [8].

The low incidence of SBN may be due to several theoretical factors including small bowel transit time, host immunologic factors, and/or epithelial toxin exposure [9–11]. Dietary factors that may increase the risk of small bowel AC may include diets high in red meat, or the consumption of smoked or salted foods [12]. There may be an increased risk of SBN with a diet rich in refined carbohydrates, and sugar [13]. Hereditary syndromes or conditions that can predispose to SBN include Muir-Torre syndrome [14], hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC), familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) and it's variants such as Gardner's Syndrome [15] Celiac Sprue, Puetz-Jeghers, Crohn's Disease[16] and Juvenile Polyposis Syndrome [17].

Primary SBNs are much rarer than those that arise from a secondary neoplastic process [16]. Metastasis from the stomach, ovary, colon and uterus can involve the small bowel by direct means or via peritoneal involvement [18]. Metastatic tumors from breast, melanoma and lung appear to spread to the duodenum by blood and lymphatic pathways.

The mean age of presentation of SBN is 64 with a range of 47-87 years [3, 19]. Obscure GI bleeding (OGIB) is the most common symptom as 50% of those with SBN present with OGIB, however it should be noted that only 4% of OGIB cases are caused by SBN [20]. Due to the vague presentation a delayed diagnosis or misdiagnosis is common [9], with an average delay of six to eight months between the time of symptom onset and diagnosis [21].

Investigations

SBN are usually discovered during the evaluation of OGIB, anemia, and abdominal pain. Abdominal X-ray may help in showing obstruction, however duodenal carcinomas especially those in the 3rd and 4th portions of the organ are often missed on barium x-ray examination [22] yielding a definite diagnosis in less than 5% of cases [23]. Colonoscopy with ileoscopy may be useful in detecting lesions in the terminal ileum and excluding a colonic source of pathology. Both sporadic duodenal adenomas and those associated with hereditary cancer syndromes have a higher risk of colorectal cancer (CRC) and these patients should be evaluated with colonoscopy [24]. Likewise those with CRC associated with hereditary cancer syndromes should be evaluated for SBN [17].

The utilization of CT enterocolysis (CTE) in the detection of SBN overcomes the individual short comings of both barium enterocolysis and conventional CT and utilizes the advantages of both into a single technique and has begun to substitute enterocolysis in clinical practice [25]. Contrast-enhanced and water-enhanced multidetector CTE has a sensitivity of 84.7-95% and 96-100 % specificity for the detection of SBN [26, 27].

Tocchi et al. found that upper GI endoscopy had a 36% false-negative result rate in identifying duodenal tumors due to depth of insertion. Push enteroscopy (PE) provides many benefits including direct visualization of lesions in the proximal duodenum and jejunum, allowing the ability to biopsy and provide therapeutic measures in cases of bleeding. The investigation of obscure bleeding by PE may find a diagnostic cause in 25-28% of cases [28, 29]. PE and Sonde enteroscopy have shown a diagnostic yield of 6% for SBN in patients undergoing the procedure for evaluation of OGIB [30]. However PE as well as CT and small bowel barium studies may fail to detect 50% of small bowel lesions [31].

Capsule endoscopy (CE) has been shown to be a safe and effective non invasive method of diagnosis for small bowel abnormalities [32, 33] and allows a more detailed inspection of the small intestine. CE has also been shown to detect duodenal adenomatous polyps in 64.3% of those who also have FAP [34]. An absolute contraindication to CE is GI obstruction. Relative contraindications to CE include pregnancy, GI motility disorders, or large diverticuli within the small bowel [35]. CE may detect more SBN than CTE in patients with OGIB having an overall accuracy of 84.7%[36].

It has been shown that CE diagnosed SBN in 9% of patients who underwent the procedure for investigation of OGIB and in 8.3% of those who were investigated for non bleeding causes [37]. However in a pooled meta-analysis it was found that CE had a 20% miss rate for SBN [38]. Similar to our case where CE failed to reveal AC of the duodenum, there are increasing reports in the literature of failure of CE to detect solitary SBN [39, 40]. It has also been shown that after an initial negative CE study a repeat CE may reveal significant lesions in 20% of cases [41]. Etiologies for failure to detect lesions by CE may be due to rapid capsule passage through the proximal small bowel, decreased visibility due to luminal contents, or failure to reach the colon. Thus, based on certain clinical scenarios a negative finding on CE may not exclude significant small bowel pathology and further investigation may be warranted.

Balloon assisted enteroscopy (BAE) utilizing either single balloon enteroscopy (SBE) or double balloon enteroscopy (DBE) offers a number of advantages when compared to other small bowel imaging studies. The advantages include visualization of the entire small bowel with the ability to provide tissue diagnosis and provide therapeutic modalities such as control of bleeding and dilation of strictures [42, 43]. Optimal visualization of the small bowel may involve both oral and anal insertion. Initial studies indicated a greater diagnostic yield and higher rate of endoscopic intervention for DBE vs. SBE[44]. However a recent study comparing SBE vs DBE revealed identical procedure times, depth of insertion, and a slight increase in identification and treatment of lesions with SBE vs DBE[45]. Studies have calculated that BAE and CE are in agreement 61-74% of the time and 96% of the time when diagnosing large tumors [46]. In regards to SBN, BAE can often find lesions originally missed by CE and is suggested as a follow up study to a negative CE exam [47]. Arakawa reported equal diagnostic yields for both CE and BAE with false negative cases of CE and BAE due to failure to detect lesions in the proximal small bowel and inaccessibility of the site, respectively. In a recent meta-analysis comparing CE and BAE, there was no significant difference in yields between the two modalities 61% vs. 56%, respectively[48]. Sub analysis of data did reveal a slight advantage in favor of CE and this appeared to be to the utilization of a single insertion approach by BAE. When BAE was performed using a dual insertion approach via the oral and anal route the yield was 74% vs. 54% for CE [48].

The failure of BAE to show superiority over CE in the detection of lesions may be due to complete evaluation of the entire small bowel in only 60-70% of cases [43, 49]. A disadvantage of the procedure is the time needed to visualize the small bowel [50], its invasiveness, and the reports of intestinal necrosis [51], perforation and acute pancreatitis [52] post procedure. Due to the failure of a true gold standard in evaluation of the small bowel utilization of both these procedures may be complementary.

Treatment and Prognosis

Duodenal AC has a shorter median overall survival rate compared with patients with tumors located in the jejunum or ileum [53]. SBNs are more common in men [54] and are higher in African Americans than those of Caucasian decent. It has been reported that SBN in African American men has increased in prevalence by 120% over the last 3 decades [55]. In regards to 5 year survival, earlier stages have a better prognosis [56]. Around 58% of patients with small intestine AC present at late stages (III and IV), in contrast with 28% of patients with CRC[55] (Table 1). The overall median survival of patients with duodenal AC has been reported as 18 months and the 5-year survival as 23% [57].

Historically treatment of SBN has relied solely upon surgery as the only curative treatment and has been divided between two techniques which are pancreatoduodenectomy (PD) and duodenal segmentectomy (DS). PD is considered to be the procedure of choice. DS, is used for more palliative measures [8]. Studies have shown that DS is a better option for distal duodenal tumors without advanced disease, in which case PD is considered a better option [8, 57, 58]. Surgical intervention has shown to provide a curative resection in 40-65% of patients. The five year survival rate for non-resected tumors being is 15-30% compared to 40-60% survival rate for those who had resection [53]. A large tumor or positive lymph node metastasis does not invalidate resection as long as a negative margin can be attained, and in terms of clearance of regional lymph nodes the difference between both procedures is negligible [57].

Chemotherapy is mainly utilized as a palliative measure and has not been well studied due to the low prevalence of AC in the small bowel. The largest published study investigating chemotherapeutic measures for small bowel AC involved 14 subjects with metastatic small bowel AC and involved a chemotherapeutic regiment containing 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) [59]. Patients had a median survival of 9 months. A more recent investigation reported advanced small bowel AC treated with infusional 5-FU-based regimens had a response rate of 37.5% and a median survival of 13 months [60]. A case report using onastat, tegafur, and gimestat (otherwise known as S-1chemotherapy) showed remission of primary AC of the duodenum [61]. Newer agents found to be effective for CRC also may have an effect on small bowel AC.

Genetic and Molecular Biology Considerations

Due to the rarity of SBN, little has been published about oncogenesis as well as clinicopathologic features [62]. An analysis of SBN found that 53% had point mutations in the Ki-ras gene [63] similar to mutations found in CRC[64], and that overall frequencies of Ki-ras and p53 gene mutations are similar in both [63].

In terms of the APC gene, SBN have a lower rate of mutations involving the APC gene compared to its involvement in CRC [63]. Duodenal carcinoma is the second most common carcinoma in FAP and the low rate of APC mutations in duodenal adenocarcinoma refer primarily to sporadic adenocarcinomas and not those associated with FAP and its variants. Thus these recent findings suggest that the APC gene is not involved with SBN in man [63, 65]. An extensive study revealed all duodenal AC tumors to be positive for mismatch repair (MMR) on genes hMHL1 and hMSH2 but no mutations were found in the mutation cluster region (MCR) of the APC gene [66]. Thus suggesting that molecular mechanism leading to the development of AC of the small intestine may be different than those leading to CRC. Cytogenetical studies on primary duodenal AC revealed several abnormalities that resulted in partial or complete losses or gains chromosomally [67]. The detection of biallelic MMR gene mutations in pediatric duodenal cancer further supports the idea of MMR deficiencies as a duodenal cancer predisposition syndrome [68].

Case Presentation

A 66 year old African-American female presented with complaints of 10 pound weight loss and a four week history of intermittent abdominal pain, nausea, and non bloody emesis. Her medical history was significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary heart disease, and peptic ulcer disease. The patient denied any significant alcohol or tobacco use. Her family history was positive for colon cancer. Physical exam and laboratory tests were unremarkable. A colonoscopy and an esophagogastroduodenosopy (EGD) to the second portion of the duodenum were performed revealing three small tubular adenomas of the colon and helicobacter pylori gastritis. She was treated with two weeks of amoxicillin 1 gram and clarithromycin 500 mg orally twice daily for two weeks.

She did well after the antibiotic therapy and was not seen again until two years later when she was hospitalized for severe, symptomatic anemia. For eight months prior to admission, she noted recurrent intermittent abdominal pain and nausea with non-bloody emesis and progressive fatigue. She denied melena or hematochezia. On admission, her hemoglobin was 5.4 gm/dl and hematocrit was 17.3%, with a normal MCV. Her stool was hemoccult positive. She required a transfusion of four units of packed red blood cells. An EGD to the second portion of the duodenum revealed mild gastritis, negative for H. pylori. A CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with oral contrast was unremarkable. An outpatient wireless capsule endoscopy was ordered; however, it was cancelled due to the reluctances of the patient to swallow the capsule.

Patient again required hospitalization for severe symptomatic anemia with hemoglobin of 5 gm/dl. Her indices and iron studies at this time were consistent with iron deficiency anemia. She denied melena, hematochezia or bloody emesis. She required another 4 unit blood transfusion. An EGD was performed and again it was unremarkable. Due to her inability to swallow the wireless capsule, the endoscope was used to deliver the capsule into the stomach. The study however was limited due to retained debris in the mid duodenum, significantly limiting visualization of the small bowel.

Patient presented three months later with symptomatic anemia, hemoglobin of 4.6 gm/dl and hematocrit of 14.2%. She required four units of packed red blood cells. Two days prior to admission, she noted black tarry stools. Physical exam was unremarkable with the exception of palpable tenderness in the epigastric and left upper quadrant.

Three way abdominal x-ray of the abdomen was performed and was unremarkable. MRA with and without contrast and CT scan of abdomen and pelvis with oral contrast showed no evidence of localized abnormality in the abdomen or pelvis in terms of solid organs or vasculature. An upper GI series with KUB was performed revealing eccentric broadband defect along the inner or medial wall of the 2nd portion of the duodenum, with the other portions being unremarkable.

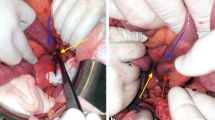

Push enteroscopy was performed which revealed a circumferential fungating mass in the 4th portion of the duodenum, which was actively oozing blood and upon further investigation it appeared the mass extended to the ligament of Treitz (Figure 1). The area was biopsied and tattooed. Pathology from biopsy revealed moderately differentiated AC with lymphovascular invasion. Patient underwent exploratory laparotomy and the small bowel was examined with the tumor being present at the ligament of Treitz. The tumor was resected en bloc and two lymph nodes were collected. The small bowel was reconnected using a primary Gambee anastamosis.

Pathology from surgical specimen revealed T3N1M0 AC, with the tumor being 4.5 centimeters in greatest dimension and showing invasion through the muscularis propria and into the sub-serosa but not through it. The resected margins were clear. Of the two lymph nodes collected one was positive for metastatic carcinoma, with the tumor nodule measuring 1.5 centimeters in diameter and showing invasion through the lymphatic capsule.

Patient was referred to oncology for consultation however did not follow up as scheduled, and has been lost to follow up care.

Conclusions

In patients presenting with OGIB, iron deficiency anemia or other warning signs and symptoms SBN, should be considered in the differential due to its insidious presentation. In terms of oncogenesis more research is needed in order to better understand its development, but evidence suggests a multi-factorial genetic cause. Options in the evaluation of small bowel pathology may require CE, BAE, and/or CTE. An initial approach may be with CE or CTE due to the fact it is non invasive with subsequent utilization of BAE if the evaluation is unrevealing or if lesions are detected that require tissue confirmation. Surgery is the best curative option in terms of treatment of these types of malignancies with PD being better for advanced diseases and DS for disease of the distal duodenum. Chemotherapeutic options are improving and providing longer survival rates and palliative benefits.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- SBN:

-

Small bowel neoplasms

- NCDB:

-

National Cancer Data Base

- SEER:

-

Surveillance Epidemiology End Results

- AC:

-

Adenocarcinoma

- HNPCC:

-

hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer

- FAP:

-

familial adenomatous polyposis

- OGIB:

-

Obscure GI bleeding

- CRC:

-

Colorectal cancer

- CTE:

-

CT enterocolysis

- PE:

-

Push enteroscopy

- CE:

-

Capsule endoscopy

- BAE:

-

Balloon assisted enteroscopy

- SBE:

-

Single Balloon enteroscopy

- DBE:

-

Double Balloon enteroscopy

- PD:

-

pancreatoduodenectomy

- DS:

-

duodenal segmentectomy

- 5-FU:

-

5-fluorouracil

- MMR:

-

Mismatch repair

- MCR:

-

mutation cluster region

- EGD:

-

esophagogastroduodenosopy

References

Moglia A, Menciassi A, Dario P, Cushieri A: Clinical update: endoscopy for small-bowel tumours. Lancet. 2007, 370 (9582): 114-116. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61066-6.

Cancer Facts & Figures 2009. 2009, Atlanta: American Cancer Society

Hatzaras I, Palest JA, Abir F, Sullivan P, Kozol R, Dudrick S, Longo W: Small-bowel tumors: epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 1260 cases from the connecticut tumor registry. Arch Surg. 2007, 142 (3): 229-235. 10.1001/archsurg.142.3.229.

Bilimoria K, Bentrem D, Wayne J, Ko C, Bennet C: Small bowel cancer in the United States: changes in epidemiology, treatement, and survival over the last 20 years. Ann Surg. 2009, 249 (1): 63-71. 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31818e4641.

Neugut AI, Jacobson JS, Suh S, Mukherjee R, Arber N: The epidemiology of cancer of the small bowel. Cancer Epidem Biomar. 1998, 7 (3): 243-251.

Lashner B: Risk factors for small bowel cancer in Crohn's diesease. Dig Dis Sci. 1992, 37 (8): 1179-1184. 10.1007/BF01296557.

Markogiannakis H, Theodorou D, Toutouzas K, Gloustianou G, Katsaragakis K, Bramis I: Adenocarcinoma of the third and fourth portion of the duodenum: a case report and review of the literature. Cases J. 2008, 1 (1): 98-10.1186/1757-1626-1-98.

Tocchi A, Mazzoni G, Puma F, Miccini M, Cassini D, Bettelli E, Tagliacozzo S: Adenocarcinoma of the Third and Fourth Portions of the Duodenum Results of Surgical Treatment. Arch Surg. 2003, 138 (1): 698-702.

DiSario JA, Burt RW, Vargas H, McWhorter WP: Small bowel cancer: epidemiological and clinical characteristics from a population based registry. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994, 89 (5): 699-701.

Ciresi DL, Scholten DJ: The continuing clinical dilemma of primary tumors of the small intestine. Am Surg. 1995, 61 (8): 698-702.

Intner T, Whang E, Ashley S: Small Intestine. Essentials of Surgery. Edited by: Stucchi JBA. 2006, Philadelphia: Saunders, 286-295.

Chow WH, Linet MS, McLaughlin LK, Hsing AW, Chien HT, Blot WJ: Risk factors for small intestine cancer. Cancer Cause Control. 1993, 4: 163-169. 10.1007/BF00053158.

Negri E, Bosetti C, La Vecchia C, Fioretti F, Conti E, Franceschi S: Risk factors for adenocarcinoma of the small intestine. Int J Cancer. 1999, 82: 171-4. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19990719)82:2<171::AID-IJC3>3.0.CO;2-T.

Rubinstein W, Weissman S: Managing hereditary gastrointestinal cancer syndromes: the partnership between genetic counselors and gastroenterologists. Nat Clin Pract Gastr. 2008, 5: 10-

Overman M: Recent advances in the management of adenocarcinoma of the small intestine. Gastrointest Cancer Res. 2009, 3: 90-96.

Gill S, Heuman D, Mihas A: Small intestinal neoplasms. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001, 33 (4): 267-282. 10.1097/00004836-200110000-00004.

Burt R: Genetics and Inherited Syndromes of Colorectal Cancer. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009, 5 (2): 119-130.

Berger A, Cellier C, Daniel C, Kron C, Riquet M, Baribier J, Cugnenc P, Landi B: Small bowel metastasis from primary carcinoma of the lung: clinical findings and outcome. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999, 94: 1884-1887. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01224.x.

Scott-Coombes DM, Williamson RCN: Surgical Treatment of Primary Duodenal Carcinoma: A Personal Series. Brit J of Surg. 1994, 81: 1472-1474. 10.1002/bjs.1800811023.

Yamagami H, Oshitani N, Hosomi S, SueKane T, Kamata N: Usefulness of Double-balloon endoscopy in the diagnosis of malignant small-bowel tumors. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008, 6 (11): 1202-1205. 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.05.014.

Wilson JM, Melvin DB, Gray GF, Thorbjarnarson B: Primary malignancies of the small bowel: a report of 96 cases and review of the literature. Ann Surg. 1974, 180: 175-179. 10.1097/00000658-197408000-00008.

Thompson N: Duodenal tumors. Current medical diagnosis and treatment: surgery. Edited by: Doherty G. 2010, New York: McGraw-Hill

Zuckerman G, Prakash C, Askin M, Lewis B: AGA technical review on the evaluation and management of occult and obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2000, 118: 201-221. 10.1016/S0016-5085(00)70430-6.

Murray MA, Zimmerman MJ, Ee HC: Sporadic duodenal adenoma is associated with colorectal neoplasia. Gut. 2004, 53 (2): 261-265. 10.1136/gut.2003.025320.

Raptopoulos V, Schwartz RK, McNicholas MM, Movson J, Pearlman J, Joffe N: Multiplanar helical CT enterography in patients with Crohn's Disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1997, 169 (6): 1545-1550.

Boudiaf M, Jaff A, Soyer P, Bouhnik Y, Hamzi L, Rymer R: Small-bowel diseases: prospective evaluation of multi-detector row helical ct enteroclysis in 107 consecutive patients. Radiology. 2004, 233 (2): 338-344. 10.1148/radiol.2332030308.

Pilleul F, Penigaud M, Milot L, Saurin JC, Chayvialle JA, Valette PJ: Possible Small-bowel neoplasms: contrast-enhanced and water-enhanced multidetector ct enteroclysis. Radiology. 2006, 241 (3): 796-801. 10.1148/radiol.2413051429.

Ell C, Remke S, May A, Helou L, Henrich R, Mayer G: The first prospective controlled trial comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with push enteroscopy in chronic gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy. 2002, 34 (9): 685-689. 10.1055/s-2002-33446.

Ge ZZ, Hu YB, Xiao SD: Capsule endoscopy and push enteroscopy in the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Chin Med J. 2004, 117 (7): 1045-1049.

Berner JS, Mauer K, Lewis BS: Push and sonde enteroscopy for the diagnosis of obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 1994, 89 (12): 2139-2142.

Kariv R, Arber N: Malignant tumors of the small intestine - new insights into a rare disease. Isr Med Assoc J. 2003, 5 (3): 188-192.

Appleyard M, Fireman Z, Glukhovsky A, Jacob H, Shreiver R, Kadirkamanathan S, Lavy A, Lewkowicz S, Scapa E, Shofti R, et al: A randomized trial comparing wireless capsule endoscopy with push enteroscopy for the detection of small-bowel lesions. Gastroenterology. 2000, 119 (6): 1431-1438. 10.1053/gast.2000.20844.

Napierkowski JJ, Maydonovitch CL, Belle LS, Brand WT, Holtzmuller KC: Wireless capsule endoscopy in a community gastroenterology practice. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005, 39 (1): 36-41.

Katsinelos P, Kountouras J, Chatzimavroudis G, Zavos C, Pilpilidis I, Fasoulas K, Paroutoglou G: Wireless capsule endoscopy in detecting small-intestinal polyps in familial adenomatous polyposis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009, 15 (48): 6075-6079. 10.3748/wjg.15.6075.

Beard C, Poulos JE, Kalle J, Kumar A, V K: Capsule endoscopy: what role for this new technology?. JAAPA. 2007, 20 (9): 32-38.

Voderholzer WA, Ortner M, Rogalla P, Beinhölzl J, Lochs H: Diagnostic yield of wireless capsule enteroscopy in comparison with computed tomography enteroclysis. Endoscopy. 2003, 35 (12): 1009-1014. 10.1055/s-2003-44583.

Cobrin GM, Pittman RH, Lewis BS: Increased diagnostic yield of small bowel tumors with capsule endoscopy. Cancer. 2006, 107 (1): 22-27. 10.1002/cncr.21975.

Lewis BS, Eisen GM, Friedman S: A Pooled analysis to evaluate results of capsule endoscopy trials. Endoscopy. 2005, 37 (10): 960-965. 10.1055/s-2005-870353.

Postgate A, Despott E, Burling D, Gupta A, Phillips R, O'Beirne J, Patch D, Fraser C: Significant small-bowel lesions detected by alternative diagnostic modalities after negative capsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008, 68 (6): 1209-1214. 10.1016/j.gie.2008.06.035.

Chong AK, Chin BW, Meredith CG: A Pooled analysis to evaluate results of capsule endoscopy trials. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006, 64 (3): 445-449. 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.007.

Bar-Meir S, Eliakim R, Nadler M, Barkay O, Fireman Z, Scapa E, Chowers Y, Bardan E: Second capsule endoscopy for patients with severe iron deficiency anemia. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004, 60 (5): 711-713. 10.1016/S0016-5107(04)02051-6.

Ross W: Small bowel imaging: multiple paths to the last frontier. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008, 68 (6): 1117-1121. 10.1016/j.gie.2008.04.045.

Arakawa D, Ohmiya N, Nakamura M, Honda W, Shirai O, Itoh A, Hirooka Y, Niwa Y, Maeda O, Ando T, et al: Outcome after enteroscopy for patients with obscure gi bleeding:diagnostic comparison between double-balloon endoscopy and videocapsule endoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009, 69 (4): 866-874. 10.1016/j.gie.2008.06.008.

May A: Balloon Enteroscopy: Single-and Double-Balloon Enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2009, 19 (3): 349-356. 10.1016/j.giec.2009.04.003.

Efthymiou M, Desmond P, Taylor AC: Single Balloon Enteroscopy Versus Double Balloon Enteroscopy, Preliminary Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010, 71 (5): AB122-123. 10.1016/j.gie.2010.03.070.

Mehdizadeh S, Ross A, Gerson L, Leighton J, Chen A, Schembre D, Chen G, Semrad C, Kamal A, Harrison EM, et al: What is the learning curve associated with double-balloon enteroscopy? Technical details and early experience in 6 u.s. tertiary care centers. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006, 64 (5): 740-750. 10.1016/j.gie.2006.05.022.

Ross A, Mehdizadeh S, Tokar J, Leighton JA, Kamal A, Chen A, Schembre D, Chen G, Binmoeller K, Kozarek R, et al: Double balloon enteroscopy detects small bowel mass lesions missed by capsule endoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 2008, 53 (8): 2140-2143. 10.1007/s10620-007-0110-0.

Chen X, Ran ZH, Tong JL: A Meta-analysis of the yield of capsule endoscopy compared to double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with small bowel diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2007, 13 (32): 4372-4378.

Gross SA, Stark ME: Initial experience with double-balloon enteroscopy at a U.S. center. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008, 67 (6): 890-897. 10.1016/j.gie.2007.07.047.

Lo SK, Mehdizadeh S: Therapeutic uses of double-balloon enteroscopy. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2006, 16 (2): 363-376. 10.1016/j.giec.2006.03.002.

Yen HH, Chen YY, Su WW, Soon MS, Lin YM: Intestinal necrosis as a complication of epinephrine injection therapy during double-balloon enteroscopy. Endoscopy. 2006, 38 (5): 542-10.1055/s-2006-925184.

Honda K, Mizutani T, Nakamura K, Higuchi N, Kanayama K, Sumida Y, Yoshinaga S, Itaba S, Akiho H, Kawabe K, et al: Acute pancreatitis associated with peroral double-balloon enteroscopy: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2006, 12 (11): 1802-1804.

Dabaja BS, Suki D, Pro B, Bonnen M, Ajani J: Adenocarcinoma of the Small Bowel Presentation, Prognostic Factors, and Outcome of 217 Patients. Cancer. 2004, 101 (3): 518-526. 10.1002/cncr.20404.

Horner MJ, Ries L, Krapcho M, Neyman N, Aminou R: Seer cancer statistics review, 1975-2006. Edited by: Health NIo. 2009, Bethesda: Government Printing Office

Haselkorn T, Whittemore AS, Lilienfeld DE: Incidence of small bowel cancer in the United States and worldwide: geographic, temporal, and racial differences. Cancer Cause Control. 2005, 16 (7): 781-787. 10.1007/s10552-005-3635-6.

Detailed guide: small intestine cancer. Edited by: Society AC. 2009, American Cancer Society, 2009:

Kaklamanos IG, Bathe OF, Franceschi D, Camarda C, Levi J, Livingstone AS: Extent of resection in the management of duodenal adenocarcinoma. Am J Surg. 2000, 179 (1): 37-41. 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)00269-X.

Han SL, Cheng J, Zhou HZ, Zeng QQ, Lan SH: The Surgical treatment and outcome for primary duodenal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Cancer. 2009, 40 (1-2): 33-37. 10.1007/s12029-009-9073-z.

Jigyasu D, Bedikian AY, Stroehlein JR: Chemotherapy for primary adenocarcinoma of the small bowel. Cancer. 1984, 53 (1): 23-25. 10.1002/1097-0142(19840101)53:1<23::AID-CNCR2820530106>3.0.CO;2-U.

Crawley C, Ross P, Norman A, Hill A, Cunningham D: The Royal marsden experience of a small bowel adenocarcinoma treated with protracted venous infusion 5-fluorouracil. Br J Cancer. 1998, 78 (4): 508-510.

Katakura Y, Suzuki M, Kobayashi M, Nakahara K, Matsumoto N, Itoh F: Remission of primary duodenal adenocarcinoma with liver metastases with s-1 chemotherapy. Dig Dis Sci. 2007, 52 (4): 1121-1124. 10.1007/s10620-006-9382-z.

Neugut AI, Marvin MR, Rella VA, Chabot JA: An overview of adenocarcinoma of the small intestine. Oncology. 1997, 11 (4): 529-536.

Arai M, Shimizu S, Imai Y, Nakatsuru Y, Oda H, Oohara T, Ishikawa T: Mutations of the Ki-ras, p53, and APC genes in Adenocarcinomas of the Human Small Intestine. Int J Cancer. 1997, 70 (4): 390-395. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(19970207)70:4<390::AID-IJC3>3.0.CO;2-R.

Bos J: Ras Oncogenes in Human Cancer: A Review. Cancer Res. 1989, 49 (17): 4682-4689.

Saurin JC, Gutknecht C, Napoleon B, Chavaillon A, Ecochard R, Scoazec JY, Ponchon T, Chayvialle JA: Surveillance of Duodenal Adenomas in Familial Adenomatous Polyposis Reveals High Cumulative Risk of Advanced Disease. J Clin Oncol. 2004, 22 (3): 493-498. 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.028.

Wheeler JM, Warren BF, Mortensen NJ, Kim HC, Biddolph SC, Elia G, Beck NE, Williams GT, Shepherd NA, Bateman AC, et al: An Insight into the genetic pathway of adenocarcinoma of the small intestine. Gut. 2002, 50 (2): 218-223. 10.1136/gut.50.2.218.

Gorunova L, Johansson B, Dawiskiba S, Andrén-Sandberg A, Mandahl N, Heim S, Mitelman F: Cytogenetically detected clonal heterogeneity in a duodenal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1995, 82 (2): 146-150. 10.1016/0165-4608(95)00032-K.

Roy S, Raskin L, Raymond VM, Thibodeau SN, Mody RJ, Gruber SB: Pediatric duodenal cancer and biallelic mismatch repair gene mutations. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2009, 53 (1): 116-120. 10.1002/pbc.21957.

Cunningham J, Aleali R, Aleali M, Brower S, Aufses J: Malignant Small Bowel Neoplasms Histopathologic Determinants of Recurrence and Survival. Ann Surg. 1997, 225: 300-306. 10.1097/00000658-199703000-00010.

North JHPM: Malignant tumors of the small intestine: a review of 144 cases. Am Surg. 2000, 66 (1): 46-51.

Howdle PDJP, Holmes GK, Houlston RS: Primary small bowel malignancy in the UK and its association with coeliac disease. QJM. 2003, 96 (5): 345-353. 10.1093/qjmed/hcg058.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-230X/10/109/prepub

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by funds provided to Dr. Georgakilas by a 2009/2010 ECU Research/Creative Activity Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

FAM, JEP, TD, and AD contributed directly and equally to patient care; PTK, SG, AGG, and JEP contributed to literature research and analysis of the data; All authors contributed in the writing and critical development of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Peter T Kalogerinis, John E Poulos, Andrew Morfesis, Anthony Daniels, Stavroula Georgakila and Alexandros G Georgakilas contributed equally to this work.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Kalogerinis, P.T., Poulos, J.E., Morfesis, A. et al. Duodenal carcinoma at the ligament of Treitz. A molecular and clinical perspective. BMC Gastroenterol 10, 109 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-10-109

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-230X-10-109