Abstract

Background

Plant WRKY DNA-binding transcription factors are key regulators in certain developmental programs. A number of studies have suggested that WRKY genes may mediate seed germination and postgermination growth. However, it is unclear whether WRKY genes mediate ABA-dependent seed germination and postgermination growth arrest.

Results

To determine directly the role of Arabidopsis WRKY2 transcription factor during ABA-dependent seed germination and postgermination growth arrest, we isolated T-DNA insertion mutants. Two independent T-DNA insertion mutants for WRKY2 were hypersensitive to ABA responses only during seed germination and postgermination early growth. wrky2 mutants displayed delayed or decreased expression of ABI5 and ABI3, but increased or prolonged expression of Em1 and Em6. wrky2 mutants and wild type showed similar levels of expression for miR159 and its target genes MYB33 and MYB101. Analysis of WRKY2 expression level in ABA-insensitive and ABA-deficient mutants abi5-1, abi3-1, aba2-3 and aba3-1 further indicated that ABA-induced WRKY2 accumulation during germination and postgermination early growth requires ABI5, ABI3, ABA2 and ABA3.

Conclusion

ABA hypersensitivity of the wrky2 mutants during seed germination and postgermination early seedling establishment is attributable to elevated mRNA levels of ABI5, ABI3 and ABI5-induced Em1 and Em6 in the mutants. WRKY2-mediated ABA responses are independent of miR159 and its target genes MYB33 and MYB101. ABI5, ABI3, ABA2 and ABA3 are important regulators of the transcripts of WRKY2 by ABA treatment. Our results suggest that WRKY2 transcription factor mediates seed germination and postgermination developmental arrest by ABA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Abscisic acid (ABA) is a phytohormone regulating plant responses to a variety of environmental stress, particularly water deprivation, notably by regulating stomatal aperture [1–4]. It also plays an essential role in mediating the initiation and maintenance of seed dormancy [5]. Late in seed maturation, the embryo develops and enters a dormant state that is triggered by an increase in the ABA concentration. This leads to the cessation of cell division and activation of genes encoding seed storage proteins and proteins required to establish desiccation tolerance [6]. Exposure of seeds to ABA during germination leads to rapid but reversible arrest in development. ABA-mediated postgermination arrest allows germinating seedlings to survive early water stress [5]. Based on ABA inhibition of seed germination, mutants with altered ABA sensitivity have been identified. These screens have led to the identification of several ABA-insensitive genes [7–13]. The transcription factors ABI3 and ABI5 are known to be important regulators of ABA-dependent growth arrest during germination [14, 15]. ABI5, an ABA-insensitive gene, encodes a basic leucine zipper transcription factor. Expression of ABI5 defines a narrow developmental checkpoint following germination, during which Arabidopsis plants sense the water status in the environment. ABI5 is a rate-limiting factor conferring ABA-mediated postgermination developmental growth arrest [5].ABI3 is also reactivated by ABA during a short development window. Like ABI5, ABI3 is also required for the ABA-dependent postgermination growth arrest [15]. However, ABI3 acts upstream of ABI5 and is essential for ABI5 gene expression [15]. In arrested, germinated embryos, ABA can activate de novo late embryogenesis programs to confer osmotic tolerance. During a short development window, ABI3, ABI5 and late embryogenesis genes are reactivated by ABA. ABA can activate ABI5 occupancy on the promoter of several late embryogenesis-abundant genes, including Em1 and Em6 and induce their expression [15, 16]. On the other hand, ABA-induced miR159 accumulation requires ABI3 but is only partially dependent on ABI5. MYB33 and MYB101, two miR159 targets, are positive regulators of ABA responses during germination and are subject to ABA-dependent miR159 regulation [17].

The family of plant-specific WRKY transcription factors contains over 70 members in Arabidopsis thaliana [18–20]. WRKY proteins typically contain one or two domains composed of about 60 amino acids with the conserved amino acid sequence WRKYGQK, together with a novel zinc-finger motif. WRKY domain shows a high binding affinity to the TTGACC/T W-box sequence [21]. Based on the number of WRKY domains and the pattern of the zinc-finger motif, WRKY proteins can be divided into 3 different groups in Arabidopsis [20].

A growing body of studies has shown that WRKY genes are involved in regulating plant responses to biotic stresses. A majority of reported studies on WRKY genes address their involvement in disease responses and salicylic acid (SA)-mediated defense [20, 22–25]. In addition, WRKY genes are involved in plant responses to wounding [26]. Although most WRKY proteins studied thus far have been implicated in regulating biotic stress responses, some WRKY genes regulate plant responses to freezing [27], oxidative stress [28], drought, salinity, cold, and heat [29–31].

There is also increasing evidence indicating that WRKY proteins are key regulators in certain developmental programs. Some WRKY genes regulate biosynthesis of anthocyanin [32], starch [33], and sesquiterpene [34]. Other WRKY genes may regulate embryogenesis [35], seed size [36], seed coat and trichome development [32, 37], and senescence [38–40].

A number of studies have suggested that WRKY genes may mediate seed germination and postgermination growth. For example, wild oat WRKY proteins (ABF1 and ABF2) bind to the box2/W-box of the GA-regulated α-Amy2 promoter [41]. A barley WRKY gene, HvWRKY38, and its rice (Oryza sativa) ortholog, OsWRKY71 act as a transcriptional repressor of gibberellin-responsive genes in aleurone cells [42]. However, it is unclear whether WRKY genes mediate ABA-dependent seed germination and postgermination growth arrest. In this study, we report that wrky2-1 and wrky2-2 mutants are hypersensitive to ABA during germination and postgermination early growth. We have analyzed genetic interactions between the wrky2 mutant and the abi3-1 and abi5-1 mutants and found that ABA hypersensitivity of the wrky2 mutants is attributable to increased mRNA levels for ABI5, ABI3 and ABI5-induced Em1 and Em6. Furthermore, ABI5, ABI3, ABA2 and ABA3 are important regulators of ABA-induced expression of WRKY2.

Results

WRKY2T-DNA insertion mutants are hypersensitive to ABA during seed germination and postgermination early growth

To analyze the molecular events in ABA-regulated germination and seedling growth, we sought to identify WRKY transcription factors associated with these growth and developmental stages. For this purpose, we screened T-DNA insertion mutants for a number of Arabidopsis WRKY genes for altered sensitivity to ABA based on their germination rates and seedling growth in MS media containing ABA. As shown in Figure 1, WRKY2 T-DNA insertion mutants wrky2-1 (Salk_020399) and wrky2-2 (Sail_739_F05) accumulated no WRKY2 transcript of expected size and exhibited increased sensitivity to ABA during seed germination and seedling growth. The two mutants display no other obvious phenotypes in morphology, growth, development or seed size (data not shown).

To determine the role of WRKY2 in seed germination and early seedling growth, wild-type and wrky2 mutant seeds were germinated on MS medium containing 0 μM, 0.5 μM, 1.0 μM, 1.5 μM, 2.0 μM ABA, and compared for differences in germination and postgerminative growth. In the absence of ABA, there was no significant difference in germination between wild-type and mutant seeds (Figure 2 and Figure 3A). In the presence of ABA, both mutants germinated later than wild type. On MS medium with 0.5 μM and 1.0 μM, 40% and 25% of wild-type seeds germinated after one day, respectively. At these two concentrations, the germination rates of the two mutants were only about half of wild type (Figure 2). On MS medium with 1.5 μM, 10% of wild-type seeds still germinated, but no wrky2-1 and wrky2-2 seeds germinated. Likewise, significantly more wild-type seeds germinated than the mutant seeds after two days on MS medium with 1.5 μM and 2.0 μM ABA (Figure 2). Early seedling growth of both mutants was also slower than that of wild type. After 7 d, 46% of wild-type but only 4% of wrky2-1 and none of wrky2-2 mutants had green cotyledons on MS medium with 1.5 μM ABA (Figure 4, 3B and 3C). These results show that wrky2 mutants are hypersensitive to ABA responses during germination and postgermination growth.

ABA dose-response analysis of germination in wrky2-1 and wrky2-2 mutants. Seeds were germinated on MS plates containing 0 μM, 0.5 μM, 1.0 μM, 1.5 μM, and 2.0 μM ABA. Plates were routinely kept for 3 days in the dark at 4°C and transferred to a tissue culture room under constant light at 22°C. Germination efficiencies (radicle emergence) of wild type and wrky2 mutants seeds for 7 d after stratification. Three independent experiments are shown, and above 100 seeds were used in each experiment.

wrky2 mutants are hypersensitive to ABA responses during postgermination growth. (A) Photographs of WT, wrky2-1 and wrky2-2 seedlings on MS medium at 7 d after the end of stratification. (B) Photographs of WT, wrky2-1 and wrky2-2 seedlings on MS medium with 1.5 μM ABA at 7 d after stratification. (C) Photographs of representative examples in A and B. (D) Photographs of representative examples in A and B in darkness.

To analyze the role of WRKY2 during the seedling growth stages, we first germinated the wild-type and wrky2 mutant seeds on MS medium for 4 d and then transferred the seedlings onto MS medium containing 0 μM, 0.5 μM, 1.0 μM, 1.5 μM, 2.0 μM, 5.0 μM, 10 μM, 20 μM, 40 μM and 80 μM ABA. No significant difference was observed between the wild type and wrky2 mutants 10 days after the transfer (data not shown).

When the germination experiments were carried out in dark, wrky2 mutants are again more sensitive to ABA responses than wild type (Figure 3). Taken together, these observations suggest that wrky2 mutants are hypersensitive to ABA responses only during seed germination and early seedling growth.

Response of wrky2mutants to ABA defines a limited developmental window

The transcription factors ABI3 and ABI5 are known to be important regulators of ABA-dependent growth arrest during germination [14, 15]. ABI3 and ABI5 are reactivated by ABA during a short development window. Given the ABA hypersensitivity of wrky2 mutants, we studied the effect of ABA on the early development of wrky2 mutants. Application of 5 μM ABA [5] within 48 h post-stratification maintained the germinated embryos of wrky2 mutants in an arrested state for several days, but did not prevent germination, whereas a significant percentage of wild-type germinated embryos escaped growth arrest and turned green (Figure 5A and 5B). ABA applied outside the 48-h time frame failed to arrest growth and prevent greening (Figure 5C). If the seeds were transferred to ABA-containing media immediately or one day after stratification, we observed that the wrky2 mutants were more sensitive to ABA responses than the wild type. However, if the seeds were transferred to ABA-containing media 2 days post-stratification, there was no significant difference between the wild type and wrky2 mutants. These results indicated that wrky2 mutants were hypersensitive to ABA responses for a short development window.

wrky2 mutants are hypersensitive to ABA responses in a short development window. (A) Seeds were germinated on MS medium 1 d after stratification, all were transferred to MS medium with 5 μM ABA. Photographs were taken 6 d after transfer. (B) Seeds were germinated on MS medium and 2 d after stratification, all were transferred to MS medium with 5 μM ABA. Photographs were taken 5 d after transfer. (C) Seeds were germinated on MS medium and 3 d after stratification, all were transferred to MS medium with 5 μM ABA. Photographs were taken 4 d after transfer.

WRKY2mediates signal pathway of ABA-dependent germination and postgermination early growth

During germination, ABA can activate de novo late embryogenesis programs to confer osmotic tolerance in arrested, germinated embryos [15]. During a short development window, ABI3, ABI5 and late embryogenesis genes are reactivated by ABA. ABI3 acts upstream of ABI5 and is essential for ABI5 gene expression. ABA induces ABI5 occupancy on the promoter of Em1 and Em6, and activates these late embryogenesis-abundant genes [15, 16]. To analyze the expression of these genes in wrky2 mutants, we germinated the wild type and wrky2 mutants on MS medium with 0 and 1.5 μM ABA for 4 or 7 days. Total RNA was isolated and analyzed using quantitative RT-PCR with gene-specific primers. As shown in Figure 6, when these seedlings have grown on MS medium without ABA 4 days post-stratification, expression of ABI5, ABI3, Em1 and Em6 was reduced in the wrky2 mutants relative to that in the wild type. At 7 days post-stratification, wild type and wrky2 mutants accumulated similar levels of transcripts for ABI3, ABI5, Em1 and Em6 (Figure 6).

RNA levels of ABI5 , ABI3 , Em1 and Em6 in wrky2 mutants and wild type. RNA was extracted from seedlings on MS medium without ABA or with 1.5 μM ABA 4 d or 7 d after the end of stratification. Relative RNA levels of 4 genes were analyzed using gene-specific primers by real-time PCR. Three independent experiments are shown by reextracting RNA from other samples. Each experiment also was executed three times.

On the other hand, on medium containing ABA, the expression levels of ABI5, ABI3, Em1 and Em6 were similar in the wild type and wrky2 mutants at 4 days post-stratification. However, at 7 days post-stratification, there were higher expression levels of these genes in wrky2 mutants than in the wild type, which was consistent with microarray analysis (Figure 6 and Table 1). By contrast at 4 days post-stratification, the expression of ABI3 and Em6 didn't decrease or decreased only slightly in wrky2 mutants, but decreased rapidly in the wild type within 7 days post-stratification. Within 7 days post-stratification, expression of AIB5 decreased faster in wild type than in wrky2 mutants. Expression of Em1 increased in wrky2 mutants 7 days post-stratification, but was unchanged in wild type (Figure 6).

These results indicated that wrky2 mutants displayed delayed or decreased expression of ABI5 and ABI3, but increased or prolonged expression of Em1 and Em6.

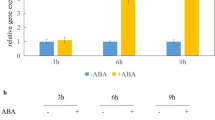

The expression of WRKY2in ABA-insensitive mutants and ABA-deficient mutants

Because wrky2 mutants are more sensitive to ABA during seed germination and postgermination growth arrest than the wild type, and wrky2 mutants also affect important genes of the ABA signal pathway in the regulation of germination and postgermination growth, we analyze whether abi3-1, abi5-1, aba2-3 and aba3-1 mutants have an effect on the expression of WRKY2. We germinated all seeds on MS medium with 0 or 1.5 μM ABA for 4 days post-stratification. We performed quantitative RT-PCR with gene-specific primers. In the absence of ABA, the expression level of WRKY2 in the wild type (Ws) was 1.2 times of that in the abi5-1 mutants. In the presence of ABA, the level of WRKY2 was 2.5-fold. On the other hand, ABA treatment led to 13.6-fold increase in accumulation of WRKY2 in the wild type and 6.5-fold increase in abi5-1 mutants (Figure 7). These results suggest ABI5 is an important regulator of ABA-induced WRKY2 expression.

RNA levels of WRKY2 in abi5-1, abi3-1, aba2-3 and aba3-1 mutants. RNA was extracted from seedlings on MS medium without ABA or with 1.5 μM ABA 4 d post-stratification. Relative RNA levels of WRKY2 were analyzed using gene-specific primers by real-time PCR. Three independent experiments are shown by reextracting RNA from other samples. Each experiment also was executed three times.

Without ABA, the level of WRKY2 in the wild type (Ler) was 1.2-fold higher than that in abi3-1 mutant. In the presence of ABA, the WRKY2 transcript level in wild type was 3.5-fold higher than that in abi3-1 mutant (Figure 7). These results indicate ABI3 maybe is a positive regulator of ABA-induced WRKY2. We also examined the expression level of WRKY2 in ABA-deficient aba2-3 and aba3-1 mutants [43, 44]. As shown in Figure 7, with ABA, the expression level of WRKY2 in the wild type was 7.5 time higher than that without ABA, but the expression levels of WRKY2 in aba2-3 and aba3-1 mutants were only 1.6 and 0.38 times of those without ABA, respectively. On the other hands, without ABA, the expression levels of WRKY2 in aba2-3 and aba3-1 mutants were 1.2 and 2.3 times of that in the wild type. These observations show elevated expression of WRKY2 by ABA treatment requires ABA2 and ABA3. These results strongly suggest that ABI5, ABI3, ABA2 and ABA3 are important regulators of ABA-induced WRKY2 expression.

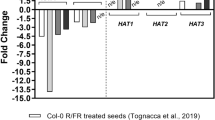

The response of WRKY2 to ABA is independent of miR159, MYB33 and MYB101

It is known that ABA-induced miR159 accumulation requires ABI3 but is only partially dependent on ABI5. Furthermore, MYB33 and MYB101, which are miR159 targets, are positive regulators of ABA responses during germination and are subject to ABA-dependent miR159 regulation [17]. Figure 8A indicates that there was no significant difference in the level of mature miR159 between wrky2 mutants and the wild type. As shown in Figure 8B and Table 1, there was no difference in levels of transcripts of MYB33 and MYB101 either. These results indicate that WRKY2-mediated ABA signaling pathway is independent of miR159 and its target genes (MYB33 and MYB101) during seed germination and postgermination growth arrest.

RNA levels of miR159 , MYB33 and MYB101 in wrky2 mutants and wild type. RNA was extracted from seedlings on MS medium without ABA or with 1.5 μM ABA 4 d or 7 d post-stratification. (A) Each lane contained 20 μg total RNA. Each experiment also was executed three times. (B) Relative RNA levels of WRKY2 were analyzed using gene-specific primers by real-time PCR. Three independent experiments are shown by reextracting RNA from other samples. Each experiment also was executed three times.

Discussion

The ability of exogenous ABA to arrest postgermination development has been used extensively to identify genes involved in ABA signaling [45]. In the present study, we discovered that wrky2-1 and wrky2-2 mutants were more sensitive than wild type to ABA responses during seed germination and postgermination early growth.

The wrky2 mutants are hypersensitive to ABA responses only within a short development window during seed germination and early seedling growth. During seed germination and early growth, the transcription factors ABI3 and ABI5 are known to be important regulators of ABA-dependent growth arrest, and their expression defines a narrow developmental checkpoint following germination [14, 15]. ABI5 is a key player in ABA-triggered postgermination growth arrest, and the abi5 mutant seeds are insensitive to growth arrest by ABA, whereas seeds of ABI5-overexpressing lines are hypersensitive to ABA [5]. ABI3 acts upstream of ABI5 and is an important regulator of germination and postgermination growth by ABA [15]. ABA-induced ABI5 also occupies the promoter of Em1 and Em6 and activates these two late embryogenesis-abundant genes [15, 16]. Lopez-Molina et al. (2001) have shown that application of 5 μM ABA within 60 h post-stratification in the wild type [5] (Ws) does not prevent germination, but arrest the germinated embryos for several days, during which both ABI5 transcripts and ABI5 proteins are detected at high levels. When applied outside the 60-h time frame, however, ABA fails to arrest growth and prevent greening and ABI5 transcripts and proteins are present at low levels [5]. Therefore, it is possible that the ABA-induced growth-arrest of wrky2 mutants might be associated with the expression level of ABI5. To test this hypothesis, we compared wild type and wrky2 mutants for analyzed ABA-regulated expression levels of ABI5 and ABI5-related important regulators during seed germination and postgermination development. We found that wrky2 mutants had higher mRNA levels of ABI5, ABI3 and ABI5-induced Em1 and Em6 than the wild type (Figure 6). The higher expression levels of these genes in the wrky2 mutants may be partly responsible for the enhanced growth arrest relative to that in the wild type in the presence of ABA (Figure 3 and 4).

With ABA treatment, miR159 accumulation requires ABI3 but is only partially dependent on ABI5 [17]. MYB33 and MYB101, which are miR159 targets, are positive regulators of ABA responses during germination [17]. Therefore we examined whether WRKY2 affected the mRNA levels of these genes. We found that the expression levels of these genes were not significantly different between wrky2 mutants and the wild type (Figure 8). These observations indicate that the response of WRKY2 to ABA during germination and early growth is independent of miR159 and its target genes (MYB33 and MYB101).

We also show that ABI5, ABI3, ABA2 and ABA3 are important positive regulators of ABA-induced WRKY2 accumulation (Figure 7). The expression levels of WRKY2 were elevated more drastically in the wild type than in abi5-1 and abi3-1 mutants after ABA treatment (Figure 7). This result indicates that these two genes are positive regulators of ABA-induced WRKY2 accumulation.

Genes encoding the enzymes for most of the steps of the ABA biosynthesis pathway have been cloned and their functions confirmed using ABA-deficient mutants for ABA1 [46], ABA2 [47, 48], ABA3 [44, 49, 50] and ABA4 [51, 52]. We analyzed the effect of ABA biosynthesis genes on WRKY2 transcripts using ABA-deficient aba2-3 and aba3-1 mutants [43, 44]. We shows that elevated expression of WRKY2 after ABA treatment requires ABA2 and ABA3, indicating that these two genes are positive regulators of ABA-induced WRKY2 accumulation (Figure 7).

Several studies have shown that ABI5 binds to the ABA-responsive DNA elements (ABREs) with an ACGT core in the promoter of Em1 and Em6, and activates their expression [15, 16]. On the other hand, other reports have shown that wild oat WRKY proteins (ABF1 and ABF2) bind to the box2/W-box of the GA-regulated α-Amy2 promoter [41], and GaWRKY1 highly activated the CAD1-A promoter by binding to W-box [34], and a barley WRKY gene, HvWRKY38, and its rice (Oryza sativa) ortholog, OsWRKY71 act as a transcriptional repressor of gibberellin-responsive genes in aleurone cells [42]. The promoter zone of WRKY2 has an ABA-responsive DNA element (CACGTGGC) containing an ACGT core, and the promoter zone of ABI5 has 6 W-box, whereas the promoter of ABI3 has 2 W-box. This raises the possibility that WRKY2, ABI3 and ABI5 are mutually regulated.

Conclusion

Transcription factors ABI5 is an important regulator of postgermination developmental arrest mediated by ABA. Postgermination proteolytic degradation of the essential ABI5 transcription factor is interrupted by perception of an increase in ABA concentration, leading to ABI5 accumulation and reactivation of embryonic genes. Here we report that wrky2-1 and wrky2-2 mutants are more sensitive to ABA responses than the wild type during seed germination and postgermination early seedling establishment. ABA hypersensitivity of the wrky2 mutants is attributable to elevated mRNA levels of ABI5, ABI3 and ABI5-induced Em1 and Em6 in the mutants. WRKY2-mediated ABA responses are independent of miR159 and its target genes MYB33 and MYB101. ABA-induced WRKY2 accumulation during germination and postgermination early growth requires ABI5, ABI3, ABA2 and ABA3, suggesting that they are important regulators of the transcripts of WRKY2 by ABA treatment. Our results suggest that WRKY2 transcription factor mediates seed germination and postgermination developmental arrest by ABA.

Methods

Plant material and growth conditions

The Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes Columbia, Wassilewskija and Landsberg erecta were used throughout this study. Seeds of the different genotypes of Arabidopsis thaliana were harvested from plants of the same age and stored for 5 weeks in the dark at 4°C. Seeds were surface-sterilized with 10% bleach and washed three times with sterile water. Sterile seeds were suspended in 0.1% agarose and plated on MS medium plus 1% sucrose. ABA (mixed isomers, Sigma) was added to the medium where indicated. Plates were routinely kept for 3 days in the dark at 4°C to break dormancy (stratification) and transferred thereafter to a tissue culture room under constant light at 22°C. Seeds of abi5-1, abi3-1, aba2-3 and aba3-1 were obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC) (Alonso et al., 2003).

Identification of the wrky2T-DNA Insertion Mutants

The wrky2-1 mutant (Salk_020399), obtained from the Arabidopsis Biological Resource Center (ABRC) (Alonso et al., 2003), contains a T-DNA insertion in the promoter of the WRKY2 gene, while wrky2-2 mutant (Sail_739_F05) is a gift of Dr. Zhixiang Chen (Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, USA). Homozygous plants of the wrky2-1 mutant were identified by two PCRs. In the first PCR, a pair of gene-specific primers designed to anneal outside of the T-DNA insertion were used, which in case of homozygosity does not produce a band of the predicted size (negative selection): forward primer 5'-ATCGTCATCATCTTCACCATTT-3' and reverse primer 5'-AACTGAAATCCTCAGTTCCGT-3'. In the subsequent PCR, the T-DNA border primer (5'-AAACGTCCGCAATGTGTTAT-3') in combination with forward primer in the first PCR. To confirm the nature and location of the T-DNA insertion, the PCR products were sequenced. To remove additional T-DNA loci or mutations from the mutants, backcrosses to wild-type plants were performed and plants homozygous for the T-DNA insertion were again identified.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

We germinated seeds of the wild type and wrky2 mutants on MS medium with or without 1.5 μM ABA for 4 or 7 days, and germinated the seeds of abi5-1, abi3-1, aba2-3, aba3-1 mutants and the wild type (Col, Ws and Ler) on MS medium with or without 1.5 μM ABA for 4 days. Harvest samples were froze immediately in liquid nitrogen, and stored at 80°C. RNA was extracted from these samples using An RNeasy Plant Mini kit (QIAgen, Valencia, CA), and DNA was removed via an on-column DNase treatment. For real-time PCR, the First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Roche, Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) was used to make cDNA from 1 μg of RNA in a 20 μL reaction volume. Each cDNA sample was diluted 1:20 in water, and 2 μL of this dilution was used as template for qPCR. Half-reactions (10 μL each) were performed with the Lightcycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I kit (Roche, Mannheim, Germany) on a Roche LightCycler real-time PCR machine, according to the manufacturer's instructions. ACT2 (AT3G18780) was used as a control in qPCR. Gene-specific primers for detecting transcripts of ACT2, WRKY2, ABI5, ABI3, Em1 and Em6 are listed in Table 2. Gene-specific primers of MYB33 and MYB101 are as described by Allen et al. (2007) [53]. The qPCR reactions (10 μL each) for these genes contained the following: 1 μL SYBR Green I reaction mix, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.5 μM forward and reverse primers and 2 μL cDNA. The annealing temperature was 52°C in all cases. A no-template control was routinely included to confirm the absence of DNA or RNA contamination. The mean value of four replicates was normalized using the ACT2 gene as the control. Standard curves were generated using linearized plasmid DNA for each gene of interest. A second set of experiments was conducted on an independent set of tissue as a control.

Northern blotting

Total RNA was isolated using the TRIZOL reagent (BRL Life Technologies, Rockville, MD). 20 μg RNA was separated by electrophoresis on denaturing 17% polyacrylamide gels, and electroblotted onto a Hybond-N+ membrane. The membrane was UV cross-linked and hybridized with PerfectHyb plus hybridization buffer (Sigma). DNA oligonucleotides complementary to miR159 were end-labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase (Roche Applied Science, Penzberg, Germany). For RNA gel blot analysis of WRKY2, 20 μg total RNA was separated on 1.5% agarose-formaldehyde gels and blotted to nylon membranes. Blots were hybridized with [α-32P]dATP labeled gene-specific probes. Hybridization was performed in PerfectHyb plus hybridization buffer (Sigma) overnight at 68°C. The membrane was then washed for 10 minutes twice with 2× SSC (1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl and 0.015 M sodium citrate) and 1% SDS and for 10 minutes with 0.1× SSC and 1% SDS at 68°C. Transcripts for WRKY2 were detected with about 1 kb before stop codon of WRKY2 cDNA as probe.

References

Hetherington AM: Guard cell signaling. Cell. 2001, 107 (6): 711-714. 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00606-7.

Assmann SM, Wang X-Q: From milliseconds to millions of years: guard cells and environmental responses. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2001, 4 (5): 421-428. 10.1016/S1369-5266(00)00195-3.

MacRobbie EAC: Signal transduction and ion channels in guard cells. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1998, 353: 1475-1488. 10.1098/rstb.1998.0303.

Himmelbach A, Iten M, Grill E: Signalling of abscisic acid to regulate plant growth. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1998, 353: 1439-1444. 10.1098/rstb.1998.0299.

Lopez-Molina L, Mongrand S, Chua NH: A postgermination developmental arrest checkpoint is mediated by abscisic acid and requires the ABI5 transcription factor in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001, 98 (8): 4782-4787. 10.1073/pnas.081594298.

Ingram J, Bartels D: The molecular basis of dehydration tolerance in plants. Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 1996, 47 (1): 377-403. 10.1146/annurev.arplant.47.1.377.

Lopez-Molina L, Chua N-H: A null mutation in a bZIP factor confers ABA-insensitivity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2000, 41: 541-547.

Finkelstein RR, Lynch TJ: The Arabidopsis abscisic acid response gene ABI5 encodes a basic leucine zipper transcription factor. Plant Cell. 2000, 12 (4): 599-610. 10.1105/tpc.12.4.599.

Gosti F, Beaudoin N, Serizet C, Webb AA, Vartanian N, Giraudat J: ABI1 protein phosphatase 2C is a negative regulator of abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell. 1999, 11 (10): 1897-1910. 10.1105/tpc.11.10.1897.

Finkelstein RR, Wang ML, Lynch TJ, Rao S, Goodman HM: The Arabidopsis abscisic acid response locus ABI4 encodes an APETALA 2 domain protein. Plant Cell. 1998, 10 (6): 1043-1054. 10.1105/tpc.10.6.1043.

Meyer K, Leube MP, Grill E: A protein phosphatase 2C involved in ABA signal transduction in Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 1994, 264 (5164): 1452-1455. 10.1126/science.8197457.

Leung J, Bouvier-Durand M, Morris PC, Guerrier D, Chefdor F, J G: Arabidopsis ABA response gene ABI1: features of a calcium-modulated protein phosphatase. Science. 1994, 264: 1448-1452. 10.1126/science.7910981.

Giraudat J, Hauge BM, Valon C, Smalle J, Parcy F, Goodman HM: Isolation of the Arabidopsis ABI3 gene by positional cloning. Plant Cell. 1992, 4 (10): 1251-1261. 10.1105/tpc.4.10.1251.

Zhang XR, Garreton V, Chua NH: The AIP2 E3 ligase acts as a novel negative regulator of ABA signaling by promoting ABI3 degradation. Genes & Development. 2005, 19 (13): 1532-1543. 10.1101/gad.1318705.

Lopez-Molina L, Mongrand S, McLachlin DT, Chait BT, Chua N-H: ABI5 acts downstream of ABI3 to execute an ABA-dependent growth arrest during germination. The Plant Journal. 2002, 32 (3): 317-328. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01430.x.

Bensmihen S, Rippa S, Lambert G, Jublot D, Pautot V, Granier F, Giraudat J, Parcy F: The homologous ABI5 and EEL transcription factors function antagonistically to fine-tune gene expression during late embryogenesis. Plant Cell. 2002, 14 (6): 1391-1403. 10.1105/tpc.000869.

Reyes JL, Chua N-H: ABA induction of miR159 controls transcript levels of two MYB factors during Arabidopsis seed germination. The Plant Journal. 2007, 49 (4): 592-606. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02980.x.

Eulgem T, Somssich IE: Networks of WRKY transcription factors in defense signaling. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2007, 10 (4): 366-371. 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.04.020.

Dong J, Chen C, Chen Z: Expression profiles of the Arabidopsis WRKY gene superfamily during plant defense response. Plant Molecular Biology. 2003, 51 (1): 21-37. 10.1023/A:1020780022549.

Eulgem T, Rushton PJ, Robatzek S, Somssich IE: The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends in Plant Science. 2000, 5 (5): 199-206. 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01600-9.

Ulker B, Somssich IE: WRKY transcription factors: from DNA binding towards biological function. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2004, 7 (5): 491-498. 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.07.012.

Asai T, Tena G, Plotnikova J, Willmann MR, Chiu W-L, Gomez-Gomez L, Boller T, Ausubel FM, Sheen J: MAP kinase signalling cascade in Arabidopsis innate immunity. Nature. 2002, 415 (6875): 977-983. 10.1038/415977a.

Zheng Z, Mosher SL, Fan B, Klessiq DF, Chen Z: Functional analysis of Arabidopsis WRKY25 transcription factor in plant defense against Pseudomonas syringae. BMC Plant Biology. 2007, 7: 2-10.1186/1471-2229-7-2.

Dellagi A, Heilbronn J, Avrova AO, Montesano M, Palva ET, Stewart HE, Toth IK, Cooke DE, Lyon GD, Birch PR: A potato gene encoding a WRKY-like transcription factor is induced in interactions with Erwinia carotovora subsp. atroseptica and phytophthora infestans and is coregulated with class I endochitinase expression. Molecular Plant-Microbe Interactions. 2000, 13 (10): 1092-1101. 10.1094/MPMI.2000.13.10.1092.

Lai Z, Vinod K, Zheng Z, Fan B, Chen Z: Roles of Arabidopsis WRKY3 and WRKY4 transcription factors in plant responses to pathogens. BMC Plant Biology. 2008, 8: 68-10.1186/1471-2229-8-68.

Hara K, Yagi M, Kusano T, Sano H: Rapid systemic accumulation of transcripts encoding a tobacco WRKY transcription factor upon wounding. Molecular and General Genetics MGG. 2000, 263 (1): 30-37. 10.1007/PL00008673.

Huang T, Duman JG: Cloning and characterization of a thermal hysteresis (antifreeze) protein with DNA-binding activity from winter bittersweet nightshade, Solanum dulcamara. Plant Molecular Biology. 2002, 48 (4): 339-350. 10.1023/A:1014062714786.

Rizhsky L, Davletova S, Liang H, Mittler R: The zinc finger protein Zat12 is required for cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase 1 expression during oxidative stress in Arabidopsis. J Biol Chem. 2004, 279 (12): 11736-11743. 10.1074/jbc.M313350200.

Seki M, Narusaka M, Ishida J, Nanjo T, Fujita M, Oono Y, Kamiya A, Nakajima M, Enju A, Sakurai T, et al: Monitoring the expression profiles of 7000 Arabidopsis genes under drought, cold and high-salinity stresses using a full-length cDNA microarray. Plant J. 2002, 31 (3): 279-292. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2002.01359.x.

Li S, Fu Q, Huang W, Yu D: Functional analysis of an Arabidopsis transcription factor WRKY25 in heat stress. Plant Cell Rep. 2009, 28 (4): 683-693. 10.1007/s00299-008-0666-y.

Qiu Y, Yu D: Over-expression of the stress-induced OsWRKY45 enhances disease resistance and drought tolerance in Arabidopsis. Environmental and Experimental Botany. 2009, 65: 35-47. 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2008.07.002.

Johnson CS, Kolevski B, Smyth DR: TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA2, a trichome and seed coat development gene of Arabidopsis, encodes a WRKY transcription factor. Plant Cell. 2002, 14 (6): 1359-1375. 10.1105/tpc.001404.

Sun C, Palmqvist S, Olsson H, Boren M, Ahlandsberg S, Jansson C: A novel WRKY transcription factor, SUSIBA2, participates in sugar signaling in Barley by binding to the sugar-responsive elements of the iso1 promoter. Plant Cell. 2003, 15 (9): 2076-2092. 10.1105/tpc.014597.

Xu YH, Wang JW, Wang S, Wang JY, Chen XY: Characterization of GaWRKY1, a cotton transcription factor that regulates the sesquiterpene synthase gene (+)-{delta}-cadinene synthase-A. Plant Physiol. 2004, 135 (1): 507-515. 10.1104/pp.104.038612.

Lagace M, Matton DP: Characterization of a WRKY transcription factor expressed in late torpedo-stage embryos of Solanum chacoense. Planta. 2004, 219 (1): 185-189. 10.1007/s00425-004-1253-2.

Luo M, Dennis ES, Berger F, Peacock WJ, Chaudhury A: MINISEED3 (MINI3), a WRKY family gene, and HAIKU2 (IKU2), a leucine-rich repeat (LRR) KINASE gene, are regulators of seed size in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005, 102 (48): 17531-10.1073/pnas.0508418102.

Ishida T, Hattori S, Sano R, Inoue K, Shirano Y, Hayashi H, Shibata D, Sato S, Kato T, Tabata S, et al: Arabidopsis TRANSPARENT TESTA GLABRA2 is directly regulated by R2R3 MYB transcription factors and is involved in regulation of GLABRA2 transcription in epidermal differentiation. Plant Cell. 2007, 19 (8): 2531-2543. 10.1105/tpc.107.052274.

Miao Y, Zentgraf U: The antagonist function of Arabidopsis WRKY53 and ESR/ESP in leaf senescence is modulated by the jasmonic and salicylic acid equilibrium. Plant Cell. 2007, 19 (3): 819-830. 10.1105/tpc.106.042705.

Robatzek S, Somssich IE: A new member of the Arabidopsis WRKY transcription factor family, AtWRKY6, is associated with both senescence- and defence-related processes. Plant J. 2001, 28 (2): 123-133. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01131.x.

Jing S, Zhou X, Song Y, Yu D: Heterologous expression of OsWRKY23 gene enhances pathogen defense and dark-induced leaf senescence in Arabidopsis. Plant Growth Regul. 2009, 58: 181-190. 10.1007/s10725-009-9366-z.

Rushton PJ, Macdonald H, Huttly AK, Lazarus CM, Hooley R: Members of a new family of DNA-binding proteins bind to a conserved cis-element in the promoters of alpha-Amy2 genes. Plant Molecular Biology. 1995, 29 (4): 691-702. 10.1007/BF00041160.

Zou X, Neuman D, Shen QJ: Interactions of two transcriptional repressors and two transcriptional activators in modulating gibberellin signaling in aleurone cells. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148 (1): 176-186. 10.1104/pp.108.123653.

Lin PC, Hwang SG, Endo A, Okamoto M, Koshiba T, Cheng WH: Ectopic expression of ABSCISIC ACID 2/GLUCOSE INSENSITIVE 1 in Arabidopsis promotes seed dormancy and stress tolerance. Plant Physiol. 2007, 143 (2): 745-758. 10.1104/pp.106.084103.

Xiong L, Ishitani M, Lee H, Zhu J-K: The Arabidopsis LOS5/ABA3 locus encodes a molybdenum cofactor sulfurase and modulates cold stress- and osmotic stress-responsive gene expression. Plant Cell. 2001, 13 (9): 2063-2083. 10.1105/tpc.13.9.2063.

Lu C, Han MH, Guevara-Garcia A, Fedoroff NV: Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in postgermination arrest of development by abscisic acid. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002, 99 (24): 15812-15817. 10.1073/pnas.242607499.

Marin E, Nussaume L, Quesada A, Gonneau M, Sotta B, Hugueney P, Frey A, Marion-Poll A: Molecular identification of zeaxanthin epoxidase of Nicotiana plumbaginifolia, a gene involved in abscisic acid biosynthesis and corresponding to the ABA locus of Arabidopsis thaliana. the EMBO Journal. 1996, 15: 2331-2342.

Cheng WH, Endo A, Zhou L, Penney J, Chen HC, Arroyo A, Leon P, Nambara E, Asami T, Seo M, et al: A unique short-chain dehydrogenase/reductase in Arabidopsis glucose signaling and abscisic acid biosynthesis and functions. Plant Cell. 2002, 14 (11): 2723-2743. 10.1105/tpc.006494.

Rook F, Corke F, Card R, Munz G, Smith C, Bevan MW: Impaired sucrose-induction mutants reveal the modulation of sugar-induced starch biosynthetic gene expression by abscisic acid signalling. The Plant Journal. 2001, 26 (4): 421-433. 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.2641043.x.

Bittner F, Oreb M, Mendel RR: ABA3 is a molybdenum cofactor sulfurase required for activation of aldehyde oxidase and xanthine dehydrogenase in Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276 (44): 40381-40384. 10.1074/jbc.C100472200.

Schwartz SH, Leon-Kloosterziel KM, Koornneef M, Zeevaart JA: Biochemical characterization of the aba2 and aba3 mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 1997, 114 (1): 161-166. 10.1104/pp.114.1.161.

North HM, De Almeida A, Boutin JP, Frey A, To A, Botran L, Sotta B, Marion-Poll A: The Arabidopsis ABA-deficient mutant aba4 demonstrates that the major route for stress-induced ABA accumulation is via neoxanthin isomers. The Plant Journal. 2007, 50 (5): 810-824. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03094.x.

Dall'Osto L, Cazzaniga S, North H, Marion-Poll A, Bassi R: The Arabidopsis aba4-1 mutant reveals a specific function for neoxanthin in protection against photooxidative stress. Plant Cell. 2007, 19 (3): 1048-1064. 10.1105/tpc.106.049114.

Allen RS, Li J, Stahle MI, Dubroué A, Gubler F, Millar AA: Genetic analysis reveals functional redundancy and the major target genes of the Arabidopsis miR159 family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007, 104 (41): 16371-16376. 10.1073/pnas.0707653104.

Acknowledgements

We thank the ABRC at the Ohio State University (Columbus, OH) for the Arabidopsis mutants. We are grateful to Dr. Zhixiang Chen (Department of Botany and Plant Pathology, Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, USA) for Arabidopsis mutants and his critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Science Foundation of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant no. KSCX2-YW-N-007), and the Hundred Talents Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, the Natural Science Foundation of Yunnan Province (grant no. 2003C0342M), and the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (grant no. 2006AA02Z129).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Authors' contributions

WJ carried out all experiments of WRKY2 gene, participated in the design of the study, drafted and edit the manuscript. DY conceived of the study, participated in the design and helped to draft and edit the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, W., Yu, D. Arabidopsis WRKY2 transcription factor mediates seed germination and postgermination arrest of development by abscisic acid. BMC Plant Biol 9, 96 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-9-96

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-9-96