Abstract

Background

The hand hygiene (HH) behaviour of the general public and its effect on illnesses are issues of growing importance. Gender is associated with HH behaviour. HH efficiency is a combination of washing efficiency and hand drying, but information about the knowledge level and HH behaviour of the general public is relatively limited. The findings of this cross-sectional study can substantially contribute to the understanding on the knowledge gap and public behaviour towards HH, thereby providing information on gender-specific health promotion activities and campaigns to improve HH compliance.

Methods

An epidemiological investigation by using a cross-sectional study design on the general public was conducted either via an online platform (SurveyMonkey) or paper-and-pen methods. The hand-washing and -drying questionnaire was used for data collection.

Results

A total of 815 valid questionnaires were collected. Majority of the respondents can differentiate the diseases that can or cannot be transmitted with poor HH, but the HH knowledge of the respondents was relatively inadequate. The female respondents had a significantly better HH knowledge than male respondents. The multiple regression analysis results also indicated that females had a significantly higher knowledge score by 0.288 towards HH than males after adjusting for age and education level. Although the majority of the respondents indicated that they performed hand cleaning under different specific situations, they admitted only using water instead of washing their hands with soap. More males than females dried their hands on their own clothing, whereas more females dried their hands through air evaporation. The average time of using warm hand dryers was generally inadequate amongst the respondents.

Conclusions

Being a female, middle-aged and having tertiary education level are protective factors to improve HH knowledge. Misconceptions related to the concepts associated with HH were noted amongst the public. Self-reported practice on hand drying methods indicated that additional education was needed. The findings of this study can provide information on gender-specific health promotion activities and creative campaigns to achieve sustained improvement in HH practices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Effective hand hygiene (HH) is important in preventing disease transmission in the clinical setting and community. The handwashing behaviour of the general public and its effect on illnesses are issues of growing importance [1,2,3,4]. Whether people can practice HH properly is uncertain. Many people overlook the importance of HH when engaging in activities that require handwashing. For example, < 40% of petting zoo visitors wash their hands upon exiting animal contact areas [2]. Handwashing with soap (HWWS) is the most effective way of removing pathogens from hands and preventing the spread of infectious diseases [5,6,7]. However, in a cross-sectional comparative study conducted in Bangladesh, a gap between perception and practice of HWWS was identified. In the study, majority of the respondents (90%) have knowledge about the importance of performing HWWS before eating and after defaecation, but only 21% and 88% respondents reported to do so, respectively [4].

Certain sociodemographic factors are associated with HH compliance. In an observational study, people who lived in urban districts, with high educational level and sufficient knowledge on infectious diseases have a high handwashing compliance rate [8]. Women are more likely to wash their hands than men after controlling for washroom characteristics and clustering effects associated with social norms [9]. In an experimental study by using unobtrusive observation of human behaviour, the presence of other people in a restroom makes written messages placed in the room as a successful reminder of handwashing amongst males [10].

HH efficiency is a combination of washing efficiency and hand drying. Empirical evidence indicated that handwashing is approximately 85% effective in removing microorganisms on hands, and hand drying provides a further reduction in transient flora [7]. Inadequately dried hands are more likely to transmit microorganisms compared with completely dried ones [11]. In comparison with scientific evidence associated with HH compliance amongst healthcare professionals [12,13,14], information about knowledge level and HH behaviour of the general public is relatively limited. Many studies have evaluated that HH behaviour focus on handwashing compliance and ignore the importance of hand drying [1, 3, 4, 8]. In a qualitative evaluation by using a grounded theory approach to understand hand drying practices amongst the public in Kenya, hand drying on a clean towel was found as an uncommon practice amongst the participants. Most women tend to dry their hands on their waist clothes when performing household chores, whereas men dry their hands on their trousers or a handkerchief [15]. Therefore, gender differences on preferred hand drying methods and the compliance of proper hand drying should be explored.

Aim of the study

This study aims to determine the knowledge level and HH behaviour of the general public and attempt to identify gender differences on this issue. Both handwashing and hand drying behaviour in terms of gender disparity were investigated. The findings of this cross-sectional study can substantially contribute to the understanding on the knowledge gap and public behaviour towards HH, thereby providing information to gender-specific health promotion activities and campaigns for the improvement of HH compliance.

Methods

Study design: An epidemiological investigation by using a cross-sectional study design.

Subjects and procedure

Respondents aged ≥18 years old and residents of Hong Kong were recruited via snowball sampling method. A platform called SurveyMonkey was used to facilitate data collection [16]. SurveyMonkey is an online survey application that can facilitate the distribution of questionnaires via email; smartphones by using applications, such as WeChat and WhatsApp; and social media platform, such as Facebook. This survey application allows participants to access the questionnaire easily, and it analyses and exports results after responses have been collected [12, 17]. It also guides respondents to complete all items before exiting, thereby minimising the frequency of missing items. Questionnaires were also distributed using paper-and-pen format to a small number of participants, such as elderly who are not smartphone users. The research team used both data collection method to ensure a good coverage of respondents from different sociodemographic backgrounds, including age groups, educational level and working status to increase the generalisability of the findings.

Instrument

The hand-washing and -drying questionnaire was constructed based on an intensive literature review on key issues related to handwashing and drying [1, 4, 8, 18,19,20,21,22,23]. This questionnaire consisted of three parts. Part 1 mainly collects the sociodemographic data and personal habits. Part 2 focuses on knowledge on HH (12 items) that requires true or false responses. These items were selected according to the common myths and fallacies of HH reported in the literature, such as the misconceptions that hands should be held under water while lathering with soap and the adequate time used for hands rubbing before rinsing. The score ranged from 0 to 12, with high score indicating considerable knowledge level on HH. Part 3 comprises items related to self-reported handwashing and drying practices, such as the most common handwashing methods under specific conditions, preferred hand drying methods and public washroom facilities. Twenty respondents took an average of 12 min to complete all items during the pilot trial via SurveyMonkey.

The questionnaire was sent to a panel of 11 experts to determine if the relevant contents were covered by the instrument. These experts, who specialise in infection control and/or public health, are based in Australia, Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia and Switzerland. A content validity index of 0.92 was achieved. Test–retest reliability was performed on 20 subjects after 2 weeks of interval. The value for intraclass correlation coefficient (single measure) of the knowledge level on HH (part 2) was 0.941 (95% confidence interval = 0.857 to 0.976, p < 0.001). The item-to-item agreements for HH practice (Part 3) between the two measurements were satisfactory (weighted kappa and kappa values = 0.40 to 1.00 for 88.9% items; > 80% agreement on response for the remaining 11.1%). However, only some items in the original questionnaire were reported here due to the scope of this paper.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics for sociodemographic characteristics, knowledge level on HH, self-reported HH and hand-drying practices of the respondents were presented. The association between categorical variables was examined using x2 test or Fisher’s exact test, where appropriate. Independent t-test was used to compare the gender differences in the knowledge score on HH. Backward multiple regression was conducted to identify the most parsimonious combination of gender and other extraneous variables in predicting knowledge score. SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corporation, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. All statistical tests were two-sided, with a significance level set of p < 0.05.

Results

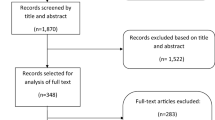

The study was conducted from February to August 2018. A total of 1002 questionnaires were collected either via SurveyMonkey (n = 945), self-administered paper-and-pen format (n = 25) or paper-and-pen format with assistance (n = 32). The completion rate of the questionnaire on the SurveyMonkey was 80.2%, and the estimated time to complete was 11 min. After excluding the respondents with significant missing items (i.e. more than half of the items were found incomplete), 758 respondents from SurveyMonkey were included. Respondents from two community centres for the elderly (completed with assistance) and one group of university students from a community college (self-administered) completed the paper-and-pen questionnaire. Thus, 815 respondents were included for the analyses.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents

The respondents were fairly distributed according to age group (18–29, 30–49, 50–59, 60 or above). Over half of these respondents were married or had partners (52.3%, n = 426), full-time job (59.5%, n = 485) and good to excellent health condition (56.4%, n = 463). The majority of the respondents attained tertiary or above education level (72.8%, n = 593) and had no comorbid illnesses (79.0%, n = 644). Only approximately 20.0% received influenza vaccination over the past 12 months (20.9%, n = 170). The characteristics were comparable between genders, except that the number of female participants was higher than the male participants with age ranging from 40 to 49 years old, are widowed/separated/divorced, and have a habit of wearing ring(s), artificial/acrylic nails (p < 0.001) or bracelets (p < 0.001). Conversely, more males than females have a habit of wearing watch (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Knowledge level towards HH

In general, the majority of the respondents can differentiate the diseases that can or cannot be transmitted with poor HH. With regards to the concepts related to HH, the knowledge level of the respondents was relatively poor. The majority of the respondents misunderstood that always keeping the hands clean may decrease the body’s defence mechanism (79.0%, n = 644), hands should be held under water while lathering (64.8%, n = 528), and an alcohol-based hand sanitiser containing 40% alcohol was sufficient for hand disinfection (56.4%, n = 460). Slightly more than half of the respondents correctly answered the items related to the statement that lathering the hands for 10 s before rinsing is insufficient for hand disinfection (57.1%, n = 465). Over 30% of the respondents believed that the temperature of water may make a difference to the cleaning effect of hand cleaning (31.3%, n = 255). In general, female respondents had a significantly better knowledge level towards HH than males (9.38 ± 1.75 vs 9.06 ± 1.73; p < 0.05) (Table 2).

Multiple regression analyses

Backward multiple regression was conducted to identify the most parsimonious combination of gender (male as referent), age group (18–29 as referent age, 30–49, 50–59, 60 or above), marital status (single as referent, married/partnered, widowed/separated/divorced), education level (primary or below as referent, secondary, tertiary or above), comorbid illnesses and working status (full-time as referent, part-time, retired/housewife/unemployed/voluntary) in predicting the knowledge score. The assumptions of linearity, data multicollinearity, homoscedasticity and distribution of residuals and the absence of influential cases were checked and met. After conducting backward regression, the model that included gender, age group (30–49 and ≥ 60 years old) and two dummy variables of education level (secondary and tertiary levels or above) was the most parsimonious combination (F [5, 809] = 27.78, p < 0.001, adjusted R2 = 0.141). The final model suggested that females had a significant higher knowledge score by 0.288 towards HH than males after adjusting for age (30–49 and ≥ 60 years old) and education level (secondary or tertiary level or above). After adjusting for other variables in the final model, the respondents aged 30–49 years old had a significant high knowledge score by 0.268, whereas respondents ≥aged 60 years old had a score reduction by 0.450 when compared with the reference group (18–29 years old). The respondents with secondary or tertiary level of education also had a significant increase in knowledge score by 1.825 and 2.482, respectively, compared with those with a low education level (primary or below, Table 3).

Self-reported hand cleaning and drying practices

The majority of the respondents indicated that they perform situational hand cleaning, including before and after handling food/cooking (> 98.0%), before eating (90.4%), after urination/defaecation (> 99.0%), after garbage bag disposal (97.1%), after sneezing/coughing (82.5%) or when the hands are visibly dirty (99.6%). If applicable, respondents performed hand cleaning after feeding a child (94.8%), caring for a sick person (99.1%), after daily work (88.5%), after touching livestock(s) (99.2%), after touching animal waste (100.0%) or after gardening (99.0%). When performing hand cleaning, significantly higher number of females than males performed HWWS than using water only (p < 0.001) in all critical moments. Over 70% of the respondents indicated that they use only ≤10 s for handwashing.

More female respondents than males tended to use paper towel to turn off a faucet or use water to splash the faucet before turning it off to avoid recontaminating the hands after washing. Over 70% of the respondents performed HH often during infectious disease outbreaks (76%). More male respondents than female ones ignored handwashing if they are in a hurry (p < 0.01), when nobody is in the washroom (p < 0.05) or when they only urinated (p < 0.001).

With regards to hand drying, more male respondents than female ones dry their hands on their own clothing (46.5% versus 37.7%, p < 0.01), whereas more female respondents dry their hands through air evaporation (70.4% versus 67.3%, p < 0.05). The respondents generally prefer using paper towels supplied by the washrooms than their own personal towels/handkerchief/tissues. The most often adopted methods for hand drying of the respondents were the use of paper towels (96.4%), followed by warm hand dryers (83.6%), jet hand dryer (78.5%) and cloth towel rolls (15.1%). The majority of the respondents shakes their hands to get rid of excess water before drying (87.5%) and limit the use of paper towels to two pieces (90.2%). Over half of the respondents rub their hands when using a warm hand dryer (51.1%). The average time for using warm hand dryers was generally inadequate amongst respondents, with over 60% of the respondents taking ≤10 s when using warm (60.9%) or jet hand dryer (64%) (Table 4).

Discussion

In general, the majority of the respondents can differentiate the diseases associated with poor HH, with female respondents having a better overall knowledge on HH than males (9.38 vs 9.06 out of 12). The misconceptions of the respondents related to HH were identified. For example, the majority of the respondents misunderstood that always keeping the hands clean may lower the body’s defence mechanism, hands should be held under water while lathering, water temperature may induce a difference in the cleaning effects of hand cleaning and lathering for 10 s before rinsing is enough for hand disinfection. In fact, the time taken for handwashing and degree of friction generated during lathering are more important than water temperature in removing dirt and microorganism, and warm water causes skin irritations and is not environmentally friendly [7, 24, 25].

The inadequacy in the knowledge level is also in accordance with the self-reported practices of the respondents. Only 12.8% of the respondents indicated that they generally lather their hands with soap for ≥20 s before rinsing, with the percentages in female respondents slightly higher than those in males (14.9% vs 7.8%). This finding agreed with an observational study conducted in Ghana, wherein the majority of the participants perform handwashing for < 5 s [9]. The results of the multiple regression analyses also indicated that females had a significantly higher knowledge score by 0.288 towards HH than males after adjusting for age and education level. The age of 30–49 years old and high educational level were the protective factors for improved HH knowledge.

Although the majority of the respondents indicated that they perform hand cleaning under different specific situations, such as before and after cooking, before eating, after urination or defaecation, after disposal of garbage bag and after sneezing/coughing; they admitted that they only use water or, in rare occasions, use alcohol-based hand rub (ABHR) or wet wipes for hand cleaning instead of performing HWWS. Empirical evidence suggested that HWWS reduces the incidence of diarrhoeal diseases, respiratory infections and influenza and has been ranked the most cost-effective intervention for disease control by breaking the chain of transmission [3, 5, 6, 9, 10]. According to predictions, significantly higher number of female respondents than male ones expressed that they performed HWWS than using water only (p < 0.001) in all critical moments. Nearly half of the respondents believed that 40% alcohol is sufficient for hand disinfection by using ABHR. However, ABHR does not kill all types of germs, such as norovirus, Clostridium difficile and some parasites; thus, it is not recommended for use when the hands are visibly dirty or greasy, such as after gardening or doing outdoor activities [24].

Significantly higher number of males than female ones ignored handwashing if they are in a hurry, when nobody is in the washroom or when they only urinated. Aunger [6] also reported that factors such as business, tiredness or hunger can discourage male respondents from performing HH behaviour in their study. HH behaviour may be affected by others in the washrooms at the same time due to clustering effect [9]. HH is considered a social norm that is an effective driver to follow other’s behaviour in a relevant social group [5, 6]. Similarly, females’ high compliance can be also associated with their tendency to practice socially acceptable behaviour [26].

Female respondents have a habit of wearing ring(s), artificial/acrylic nails or bracelets. Conversely, more males than females have a habit of wearing a watch. The bacterial load was 2.63-fold higher on ringed hands than on nonringed hands significantly [27, 28]. Wearing rings other than a wedding ring, a bracelet or a watch and having long nails were associated with poor HH amongst hospital workers [29]. Therefore, the public should be reminded to pay special attention to these regions during handwashing.

Over 70% of the respondents perform HH often during infectious disease outbreaks. The association between HH behaviour and H1N1 or SARS pandemics suggested that public education campaigns are effective in altering HH behaviour during the peak periods of outbreak occurrences [30].

With regards to hand drying, more males than females dry their hands on their own clothing, whereas more females dry their hands through air evaporation than males. Drying hands on dirty clothes can compromise the benefits of handwashing [15]. Hands that are inadequately dried are more likely to transmit microorganisms when compared with those that have been completely dried [11]. Over half of the respondents rub their hands when using a warm hand dryer. The manner by which users place their hands under the hand dryer may also affect the number of remaining bacteria on hands. Yamamoto et al. [31] used a contact-plate method to evaluate the effects of hot air dryers when the hands are rubbed together or stationary. The rubbing process may tend to draw out commensal bacteria to the skin’s surface from deep inside the pores and under the fingernails. However, additional scientific evidence should be gathered to verify this causal relationship.

The most often adopted methods for hand drying of the respondents were the use of paper towels, followed by warm hand dryers, jet hand dryers and cloth towel rolls. Similar to the results of previous studies, paper towel is the most common hand-drying method [5, 32]. Paper towels can effectively dry hands, remove bacteria and cause less contamination in washrooms [33]. However, the use of paper towels can have adverse effects on waste disposal and environmental sustainability [34]. By contrast, conventional hand dryers have less environmental impact than paper towels [34]. However, conventional hand dryers are much slower than paper towels or jet hand dryers, taking approximately 45 s to eliminate only 3% of residual water [11]. The average time for using warm hand dryers was generally inadequate amongst respondents, with the majority of the respondents using ≤10 s when using warm or jet hand dryers. As a result, a significant amount of water remaining on the hands may easily recontaminate the hands after touching the surface environment, such as door handles upon leaving washrooms. More female respondents than males tend to use paper towels to turn off a faucet or use water to splash the faucet before turning it off to avoid recontaminating the hands after washing. However, this practice can increase the use of water and paper towels [24]. Hands-free faucet with motion sensor, doors with automatic control or even washrooms without doors were recommended.

The findings of this cross-sectional study contributed to the understanding on the knowledge gap and public behaviour towards HH and the gender differences towards this issue. This information can inform gender-specific health promotion activities and creative campaigns to improve HH compliance and achieve sustained improvement in HH practices.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. HH is a socially desirable and morally laden behaviour. Therefore, the respondents may over-report the situation. Future studies that will adopt the nonobtrusive monitoring of HH behaviour may be conducted to provide an unbiased evaluation of actual behaviour. The network of the research team used convenience sampling. A relatively high percentage of the respondents attained tertiary education or above which may have an effect on HH behaviour. Quota sampling that takes into account age distribution and socioeconomic status may be considered in future surveys for a representative sample. Sanitation and facility in washrooms are the major factors affecting people’s handwashing practices [4, 35]. Future studies should be carried out to understand how washroom facilities can induce HH behaviour. HH knowledge and practices may also vary according to ethnicity and its associated washroom facilities. A wide-scale survey that compares the knowledge and HH behaviour of people residing in underdeveloped, developing and developed countries should be conducted to understand this topic from an international perspective.

Conclusion

The study results showed that female respondents generally have a better knowledge level and more favourable HH behaviour than male ones. Being a female, middle-aged and having tertiary education level were the protective factors for improved HH knowledge. Misconceptions related to the concepts that are associated with HH were noted amongst the public. The most often adopted method for hand drying of the respondents was the use of paper towels. Self-reported practice on hand drying methods indicated that additional education was needed. The findings of this epidemiological investigation can provide information to gender-specific health promotion activities and creative campaigns to achieve sustained improvement in HH practices.

Abbreviations

- ABHR:

-

alcohol-based hand rub

- HH:

-

hand hygiene

- HWWS:

-

handwashing with soap

References

Borchgrevink CP, Cha JM, Kim SH. Hand washing practices in a college town environment. J Environ Health. 2013;75(8):18–24.

Erdozain G, KuKanich K, Chapman B, Powell D. Observation of public health risk behaviours, risk communication and hand hygiene at Kansas and Missouri petting zoos – 2010-2011. Zoonoses Public Health. 2012;60:304–10.

Hirai M, Graham JP, Mattson KD, Kelsey A, Mukherji S, Cronin AA. Exploring determinants of handwashing with soap in Indonesia: a quantitative analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2016;13:868 (15 pages). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13090868.

Rabbi SE, Dey NC. Exploring the gap between hand washing knowledge and practices in Bangladesh: a cross-sectional comparative study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(89) http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/13/89.

Anderson JL, Warren CA, Perez E, Louis R, Phillips S, Wheeler J, et al. Gender and ethnic differences in hand hygiene practices among college students. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:361–8.

Aunger R, Greenland K, Ploubidis g SW, Oxford J, Curtis V. The determinants of reported personal and household hygiene behavior: a multi-country study. PLoS One. 2016;35. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159551.

Todd ECD, Michaels BS, Smith D, Greig JD, Bartleson CA. Outbreaks where food workers have been implicated in the spread of foodborne disease. Part 9. Washing and drying of hands to reduce microbial contamination. J Food Prot. 2010;73(10):1937–55 http://www.experts.com/content/articles/Ewen-Todd-Food-worker-paper-9.pdf.

Tao SY, Cheng YL, Lu Y, Hu YH, Chen DF. Handwashing behaviour among Chinese adults: a cross-sectional study in five provinces. Public Health. 2013;127(2013):620–8.

Mariwah S, Hampshire K, Kasim A. The impact of gender and physical environment on the handwashing behaviour of university students in Ghana. Tropical Med Int Health. 2012;17(4):447–54. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02950.x.

Judah G, Aunger R, Schmidt W-P, Michie S, Granger S, Curtis V. Experimental pretesting of hand-washing interventions in a natural setting. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(S2):S405S411.

Patrick DR, Findon G, Miller TE. Residual moisture determines the level of touch-contact associated bacterial transfer following hand washing. Epidemiol and Infect. 1997;119:319–25.

Kingston LM, Slevin BL, O’Connell NH, Dunne CP. Hand hygiene: attitudes and practices of nurses, a comparison between 2007 and 2015. Am J Infect Control. 2017;45(2):1300–7.

Pineles LL, Morgan DJ, Limper HM, Weber SG, Thom KA, Perencevich E, et al. Accuracy of a radiofrequency identification (RFID) badge system to monitor hand hygiene behavior during routine clinical activities. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(2):144–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2013.07.014.

Szilágyi L, Haidegger T, Lehotsky A, Nagy M, Csonka EA, Sun X, et al. A large-scale assessment of hand hygiene quality and the effectiveness of the “WHO 6-steps”. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13(249). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-13-249.

Person B, Schilling K, Owuor M, Ogange L, Quick R. A qualitative evaluation of hand drying practices among Kenyans. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74370. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/21160/cdc_21160_DS1.pdf.

SurveyMonkey. Mateo, California. https://www.surveymonkey.com.

SurveyMonkey. SurveyMonkey User Manual. 2011. https://s3.amazonaws.com/SurveyMonkeyFiles/UserManual.pdf.

Alharbi SA, Salmen SH, Chinnathambi A, Alharbi NS, Zayed ME, Al-Johny BO, et al. Assessment of the bacterial contamination of hand air dryer in washrooms. Saudi J Bio Sci. 2016;23:268–71.

Gustafson DR, Vetter EA, Larson DR, Ilstrup DM, Maker MD, Thompson RL, et al. Effects of 4 hand-drying methods for removing bacteria from washed hands: a randomized trial. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2000;75:705–8.

Kratzke C, Short M, Filippo BS. Promoting safe hygiene practices in public restrooms: a pilot study. J Environ Health. 2014;77(4):8–12 Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25603617.

Margas E, Maguire E, Berland CR, Welander F, Holah JT. Assessment of the environmental microbiological cross contamination following hand drying with paper hand towels or an air blade dryer. J Appl Microbiol. 2013;115:572–82.

Pang J, Chua SWJL, Hsu L. Current knowledge, attitude and behavior of hand and food hygiene in a developed residential community of Singapore: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:577. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1910-3.

Snelling AM, Saville T, Stevens D, Beggs CB. Comparative evaluation of the hygienic efficacy of an ultra-rapid hand dryer vs conventional warm air hand dryers. J Appl Microbiol. 2011;110:19–26.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Show me the science – how to wash your hands. CDC24/7: Saving Lives, Protecting People™. https://www.cdc.gov/handwashing/show-me-the-science-handwashing.html.

Jensen D, Schaffner D, Danyluk M, Harris L. Efficacy of handwashing duration and drying methods. Int Assn Food Prot. 2012. https://iafp.confex.com/iafp/2012/webprogram/Paper2281.html.

Johnson HD, Sholcosky D, Gabello K, Ragni R, Ogonosky N. Sex differences in public restroom handwashing behaviour associated with visual behaviour prompts. Percept Mot Skills. 2003;97:805–10.

HandInScan. Rings, watches, bracelets and nails – how do they affect hand hygiene? Debrecen, Hungary: Hand In Scan. http://www.handinscan.com/rings-watches-bracelets/.

Fagernes M, Lingaas E. Factors interfering with the microflora on hands: a regression analysis of samples from 465 healthcare workers. J Adv Nurs. 2011;67(2):297–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05462.x.

Hautemaniere A, Cunat L, Diguio N, Vernier N, Schall C, Daval M-C, Ambrogi V, Tousseul S, Hunger PR, Hartemann P. Factors determining poor practice in alcoholic gel hand rub technique in hospital workers. J Infect Public Health. 2010;3:25–34.

Park JH, Cheong HK, Son DY, Kim SU, Ha CM. Perceptions and behaviors related to hand hygiene for the prevention of H1N1 influenza transmission among Korean university students during the peak pandemic period. BMC Infect Dis 2010;10:222 (8 pages). http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/10/222.

Yamamoto Y, Ugai K, Takahashi Y. Efficiency of hand drying for removing Bacteria from washed hands comparison of paper towel drying with warm air drying. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26(03):316–20.

Edwards D, Monk-Turner E, Poorman S, Rushing M, Warren S, Willi J. Predictors of hand-washing behavior. Soc Behav Personal. 2002;30:751–6.

Huang C, Ma W, Stack S. The hygienic efficacy of different hand-drying methods: a review of the evidence. In Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(8):791–8.

Joseph T, Baah K, Jahanfar A, Dubey B. A comparative life cycle assessment of conventional hand dryer and roll paper towel as hand drying methods. Sci Total Environ. 2015;515-516:109–17.

To KG, Lee JK, Nam YS, Trinh OTH, Do DV. Hand washing behaviour and associated factors in Vietnam based on the multiple indicator cluster survey, 2010-2011. Glob Health Action. 2016;9:29207 https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v9.29207.

Acknowledgements

We extend our appreciation to the participants who offered their support to this study.

Funding

No funding support was received for this study, except that the package fee of the SurveyMonkey was covered by the Squina International Centre for Infection Control, School of Nursing, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LS was the principal investigator, conceived the study and its original design. LS, SY, KL and SL involved in the instrument validation. LS, ZS, SY KL and SL collected the data. LS and ZS drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Nursing (HSEARS20171228007), The Hong Kong Polytechnic University. Participation to this survey was voluntary, and the confidentiality of the data was strictly observed. Participants were fully aware of the purpose of the study before proceeding with the online-based survey. The institutional review board of our university approved the form of consent indicated by completing the survey.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Suen, L.K.P., So, Z.Y.Y., Yeung, S.K.W. et al. Epidemiological investigation on hand hygiene knowledge and behaviour: a cross-sectional study on gender disparity. BMC Public Health 19, 401 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6705-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6705-5