Abstract

Background

Prediction of preeclampsia is a challenge to overcome. The vast majority of prospective studies in large general obstetric populations have failed in the purpose of obtain a useful and effective model of prediction, sometimes based on complex tools unavaible in areas where the incidence of preeclampsia is the highest. The goal of this study was to assess mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) levels at 19–21, 27–29 and 37–39 weeks of gestation and performance of screening by MAP for the prediction of preeclampsia in a Brazilian cohort of healthy nulliparous pregnant women.

Methods

This was a cohort approach to a secondary analysis of the Preterm SAMBA study. Mean arterial blood pressure was evaluated at three different time periods during pregnancy. Groups with early-onset preeclampsia, late-onset preeclampsia and normotension were compared. Increments in mean arterial blood pressure between 20 and 27 weeks and 20 and 37 weeks of gestation were also calculated for the three groups studied. The accuracy of mean arterial blood pressure in the prediction of preeclampsia was determined by ROC curves.

Results

Of the 1373 participants enrolled, complete data were available for 1165. The incidence of preeclampsia was 7.5%. Women with early-onset preeclampsia had higher mean arterial blood pressure levels at 20 weeks of gestation, compared to the normotensive group. Women with late-onset preeclampsia had higher mean arterial blood pressure levels at 37 weeks of gestation, than the normotensive groups and higher increases in this marker between 20 and 37 weeks of gestation. Based on ROC curves, the predictive performance of mean arterial blood pressure was higher at 37 weeks of gestation, with an area under the curve of 0.771.

Conclusion

As an isolated marker for the prediction of preeclampsia, the performance of mean arterial blood pressure was low in a healthy nulliparous pregnant women group. Considering that early-onset preeclampsia cases had higher mean arterial blood pressure levels at 20 weeks of gestation, future studies with larger cohorts that combine multiple markers are needed for the development of a preeclampsia prediction model.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The prediction of preeclampsia is challenging. It is a complex syndrome, with multiple phenotypes, each with its own particularities of pathophysiology and clinical manifestations [1]. Effective prediction of the condition would represent an important strategy against adverse outcomes of maternal and perinatal health.

The majority of prospective studies in large general obstetric populations have demonstrated a modest capacity to predict preeclampsia by clinical risk factors, and approximately only a third of these cases are identified [2]. A prediction model using a combination of biomarkers and uterine artery Doppler has improved the diagnostic rate in early-onset cases, where disease manifestation occurs before 34 weeks of gestation. However, late-onset cases of preeclampsia (with manifestation occurring at or after 34 weeks) are the majority of cases in most clinical settings. The application of such an expensive technological screening model in low and middle-income countries is unfeasible, exactly the locations where there is a higher prevalence of preeclampsia [2,3,4].

Blood pressure measurement is part of routine surveillance during antenatal care. High blood pressure may be the first sign of a hypertensive disorder and is a diagnostic tool. Oscillations in BP measurements in a pregnant woman may reflect a trend for hypertensive disorder, and is a predictive test [5]. Since the sixties, several second-trimester studies have been reported on the use of blood pressure measurement for preeclampsia screening. There have been contradictory results concerning detection rates, which range from 8 to 93%. These different results were due to distinct diagnostic concepts of preeclampsia, diverse methods of population screening and also cutoff values used to define a positive screening test [6]. Futhermore, very few studies that specifically enrol nulliparous pregnant women have been carried out. There is actually a lack of information on this group, which is considered to be at high risk for preeclampsia [7]. The strongest known risk factor, which is a personal history of preeclampsia cannot be applied to this particular group of nulliparous women [3].

Thus, to assess the accuracy of mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) in a group of nulliparous pregnant women, this study showed the distribution of MAP levels at 19–21, 27–29 and 37–39 weeks of gestation and evaluated the accuracy of MAP at these three different time periods (basically second and third semesters) as a predictor of preeclampsia.

Methods

This was a secondary analysis of the Preterm SAMBA study, a multicenter cohort study performed in 5 different centers in Brazil. From July 2015 to March 2018, 1200 healthy nulliparous pregnant women were enroled and received follow-up during prenatal care, including only singleton pregnancies, without any fetal malformations or previous chronic maternal disease [8]. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from relevant institutional review boards and competent authorities of each center where the study was conducted. More detailed information on the study design and methods used in this study have already been previously published [9].

Participants and procedures

Criteria for participant enrollment were nulliparous women with singleton pregnancies between 19 and 21 weeks of gestation. Exclusion criteria included: previous history of chronic hypertension, use of medication, fetal malformations, diabetes mellitus, nephropathy, autoimmune diseases (systemic erythematous lupus or antiphospholipid syndrome), sickle cell disease, uterine malformations, previous cervical surgery, previous cerclage, history of 3 or more abortions, HIV infection, chronic use of corticosteroids or aspirin or calcium above 1 g/day or fish oil above 2.7 g/day or vitamin C above 1000 mg/day or vitamin E above 400 UI/day or heparin. This criteria is in accordance with another cohort study published previously [9].

At least three routine hospital visits were scheduled. Systolic and diastolic blood pressure of the women were measured, according to standard clinical procedure on the 3 occasions: at 19–21 weeks, 27–29 weeks and 37–39 weeks of gestation, using a manual sphyngomanometer, calibrated according standard procedures and using the same model in all participating centres. In these 3 occasions information about proteinuria was obtained based on a regular urinalysis performed in the routine prenatal care (in the first trimester and in the third trimester).

During the first visit, maternal characteristics and medical history were recorded. In addition, blood and hair samples were collected and stored appropriately in a biobank for subsequent analysis by metabolomics technology. Gestational age was estimated from the date of the last menstrual period and confirmed by an early ultrasonography performed before 20 weeks. For each scheduled visit, blood pressure was measured 3 times. Women were allowed to rest for 15 min before the first blood pressure measurement was performed. Between blood pressure measurements, the investigator waited for at least 2 min. During the examination, participants remained in a sitting position, with their right arm supported at the level of their heart. An adult blood pressure cuff was used, selecting the proper size for each participant. Pressure reading at phase V of Korotkoff sounds corresponded to diastolic pressure. Mean arterial blood pressure was obtained by the equation (2DBP + SBP)/3. The mean blood pressure at each gestational age for the three measurements was obtained by the average of three mean blood pressure measurements [BPm = (BP1m + BP2m + BP3m)/3]. We also calculated the difference in mean blood pressure with measurements at 19–21 weeks and 27–29 weeks and measurements at 19–21 weeks and 37–39 weeks. Calculation was made in two steps: first, the difference was determined for each woman; and second, the mean difference was calculated.

Outcome

Preeclampsia was the main outcome of this analysis. It was defined as the onset of hypertension (systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or more and/or diastolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg or more) after 20 weeks of gestation, measured on at least two different occasions, in conjunction with proteinuria (≥300 mg/day or at least 1 g/L [1+] on dipstick testing or spot urine protein/creatinine ≥30 mg/mmol [0.3 mg/mg]) or any signs of organ dysfunction [10]. Systemic complications were defined as: hematological complications (thrombocytopenia, disseminated intravascular coagulation or hemolysis); hepatic dysfunction (elevated transaminases); neurological dysfunction (examples include eclampsia, altered mental status, blindness, stroke or more commonly hyperreflexia when accompanied by clonus, severe headache when accompanied by hyperreflexia, persistent visual scotomata); renal dysfunction (creatinine ≥1.2 mg/dL) [10].

After delivery, each woman was classified as having a normal pregnancy (control group) or preeclampsia (case group). Cases were categorized into early-onset preeclampsia (women who developed preeclampsia before 34 weeks of gestation) and late-onset preeclampsia (women who developed preeclampsia after 34 + 1 weeks of gestation) [11] .

Statistical analysis

Initially, the three groups were compared regarding sociodemographic characteristics of women using a Chi-square design-based test. Mean arterial blood pressure was then compared among the three groups (early-onset preeclampsia, late-onset preeclampsia and normotensive) using Student’s t-test. The mean difference in MBP measured at 27 and 37 weeks was estimated and compared to values at 20 weeks. Finally, we checked to see whether mean arterial blood pressure had any predictive power at three time periods (20, 27 or 37 weeks of gestation) by comparing the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curves (AUROC). Analyses were performed using SPSS and Stata software.

Results

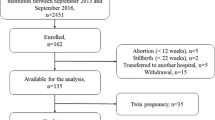

Of the 1373 participants recruited for Preterm SAMBA study, follow-up of 1165 women was provided (Fig. 1). In our cohort, the incidence of preeclampsia was 7.5% (87 cases) of whom 14 (16.1%) had early-onset preeclampsia (data not shown). The sociodemographic characteristics of women who developed preeclampsia and were analyzed according to subtypes and controls are shown in Table 1. There were no differences between preeclampsia and control groups. Throughout the gestation period, we observed that MAP showed an increasing trend in the three participating groups (Fig. 2). MAP in the early-onset preeclampsia group showed the highest value at 20 weeks of gestation, compared to the control group (p value = 0.02) (Table 2). Specifically, the increment was higher in the late-onset preeclampsia group compared to the control group, in both stages of gestation: from 20 to 27 weeks and from 20 to 37 weeks of gestation, with a p value of 0.012 and 0.003, respectively (Table 2).

When compared to the early-onset preeclampsia group, there was no difference in increment. The predictive power of mean arterial blood pressure was assessed through ROC curves, and this marker showed the highest accuracy at 37 weeks of gestation with an area under the curve of 0.771 (Table 3 and Figs. 3, 4, 5). In our cohort, there were 2 cases of eclampsia and 6 cases of HELLP syndrome, characterized by hemolysis, low platelet count and elevated hepatic transaminases (data not shown).

Discussion

Mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) has remained the target of scientific research in quest for the prediction of preeclampsia over time. It is a feasible tool and part of antenatal surveillance. Few studies have shown blood pressure patterns among low- risk nulliparous pregnant women [12,13,14,15]. Our cohort study of nulliparous low-risk pregnant women showed patterns of mean arterial blood pressure measured during the second half of pregnancy. The observation of arterial blood pressure distribution throughout pregnancy is an essential component of antenatal care strategy. This marker can be obtained from medical records usually gathered from prenatal cards that are easily available in health care services around the world.

In uncomplicated pregnancies, arterial blood pressure pattern usually consists of a steady decrease in blood pressure during the first half of pregnancy, then an increase until the time of delivery [16]. In contrast, in women with hypertensive disorder (gestational hypertension or preeclampsia) blood pressure is generally stable during the first half of pregnancy, increasing until delivery. In 2001, a study analyzing more than 2000 series of blood pressure systematically sampled by ambulatory monitoring showed that while diastolic blood pressure increases 7% between the middle of gestation and delivery in the normotensive group, this increment is around 12 and 15% in the hypertensive group [17]. Similarly, in our study there was an increment of 5.2% in mean arterial blood pressure in the normotensive group, compared to 13.3% in the late-onset preeclampsia group, with a significant difference between both (p = 0.003). In our study, the increment observed among late-onset preeclampsia cases was superior to the value seen among the early-onset preeclampsia group. We hypothesized that it was possible that the latter group had already started antihypertensive medication at 27 and 37 weeks of gestation. The lack of information about the exact time when antihypertensive medication was initiated was a weakness of our study.

Although we demonstrated that women with early-onset preeclampsia had a higher MAP at 20 weeks of gestation than the remaining participants, MAP performance was modest as a predictor, with an Area Under the Curve of only 0.619. This is not in accordance with a systematic review from 2008, which demonstrated that mean arterial blood pressure measured during the first or second trimester of gestation in a general low-risk pregnant population was a better predictor of preeclampsia, with an Area Under the Curve of 0.76. For the high-risk pregnant women group, this review indicated that diastolic blood pressure is the best predictor of preeclampsia, when measured between 13 and 20 weeks of gestation [18]. The very few cases of preeclampsia may possibly explain the modest accuracy found in our cohort, specially the very few cases of early-onset preeclampsia. In our analysis, the highest accuracy was achieved at 37 weeks of gestation, with an AUC of 0.771. Despite this number, prophylatic measures are totally unfeasible at this gestational age, considering the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. Regardless of the time period when preeclampsia is clinically established, it may be triggered in earlier stages of gestation [19, 20].

Furthermore, some studies have demonstrated a higher predictive power when MAP is measured during the first trimester of pregnancy [6, 15, 21], particulary when combined with other maternal factors. Participants were enrolled during the second trimester of gestation. Therefore, such data is not available, representing a weakness of our study. However, a cohort of more than 70,000 pregnant women found a similar detection rate of preeclampsia, with MAP measurement at 11–13 weeks or 19–24 weeks of gestation [22]. It is already known that the introduction of low-dose aspirin before 16 weeks of gestation in a group at high-risk for preeclampsia can reduce the incidence of EO-PE by almost 62% [23, 24]. This reinforces the importance of a proposed pregnancy care model in early pregnancy to identify possible life-threatening maternal and fetal health conditions [25]. Nevertheless, this should not reduce the significance attributed to a “second-look” prediction in the middle of gestation - in the second trimester - considering that it is still possible to redefine pregnancy management at this time period, including the frequency of visits, addressing content, time, method and place of delivery [22, 26].

Our study has many strengths. First, this was a prospective examination of a large population of low-risk nulliparous pregnant women. Second, there was data recording of maternal characteristics and medical history to identify risk factors associated with preeclampsia. Furthermore, we measured arterial blood pressure with a manual sphygmomanometer which was standardized in the protocol for noninvasive blood pressure monitoring [6]. On the other hand, it is known that there is concern about the clinical performance and safety of these instruments. Although BMI had been registered at enrolment, a weakness of our study was that participants were not segregated by weight. This can add a significant bias, despite the exclusion of women with comorbidities. Obesity was twofold higher among women with preeclampsia than among controls. Nevertheless, weight was not an exclusion factor. MAP is known to be dependent on weight [27]. However, a cuff of the appropriate size for each patient weight was selected for blood pressure measurement. Another important limitation of our study was the very few cases of early-onset preeclampsia, as our cohort was built with healthy participants. This can impact the results, weakening some analysis. This is why we consider future studies with larger cohorts to be important.

Conclusion

In the last 20 years, improvement in diagnostic tools has led to the prevention and prediction of different conditions, including obstetric health issues. Therefore, considerable effort has been devoted to identifying and modifying individual risk factors during the first half of pregnancy [25, 26]. Close surveillance of the mother and offspring may help to decide the best time for delivery. Furthermore, owing to the complexity of preeclampsia and its multifactorial etiology, the predictive power seems to be correlated with the association of distinct factors in a prediction model, and is not related to a unique isolated risk factor or biomarker [28]. Therefore, future studies should be conducted to analyze mean arterial blood pressure in combination with other strategies, to obtain a predictive algorithm for preeclampsia, particularly in the challenging nulliparous group.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed during the current research are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The participating women did not give their consent to make their own data publicly available.

Abbreviations

- AUROC:

-

Area under the receiver-operating characteristic curves

- BP:

-

Blood pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- EO-PE:

-

Early-onset preeclampsia

- LO-PE:

-

Late-onset preeclampsia

- MAP:

-

Mean arterial blood pressure

- PE:

-

Preeclampsia

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

References

Chaiworapongsa T, Chaemsaithong P, Yeo L, Romero R. Pre-eclampsia part 1: current understanding of its pathophysiology. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2014;10(8):466–80.

Poon LC, Nicolaides KH. First-trimester maternal factors and biomarker screening for preeclampsia. Prenat Diagn. 2014;34(7):618–27.

O'Gorman N, Wright D, Poon LC, Rolnik DL, Syngelaki A, de Alvarado M, et al. Multicenter screening for pre-eclampsia by maternal factors and biomarkers at 11-13 weeks' gestation: comparison with NICE guidelines and ACOG recommendations. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49(6):756–60.

Abalos E, Cuesta C, Grosso AL, Chou D, Say L. Global and regional estimates of preeclampsia and eclampsia: a systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013;170(1):1–7.

Sibai B, Dekker G, Kupferminc M. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet. 2005;365(9461):785–99.

Poon LC, Kametas NA, Pandeva I, Valencia C, Nicolaides KH. Mean arterial pressure at 11(+0) to 13(+6) weeks in the prediction of preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2008;51(4):1027–33.

(UK). NCCfWsaCsH. Hypertension in Pregnancy. The managment of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. London: RCOG press; 2010.

Cecatti JG, Souza RT, Sulek K, Costa ML, Kenny LC, McCowan LM, et al. Use of metabolomics for the identification and validation of clinical biomarkers for preterm birth: preterm SAMBA. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2016;16(1):212.

Kenny LC, Black MA, Poston L, Taylor R, Myers JE, Baker PN, et al. Early pregnancy prediction of preeclampsia in nulliparous women, combining clinical risk and biomarkers: the screening for pregnancy endpoints (SCOPE) international cohort study. Hypertension. 2014;64(3):644–52.

Tranquilli AL, Dekker G, Magee L, Roberts J, Sibai BM, Steyn W, et al. The classification, diagnosis and management of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: a revised statement from the ISSHP. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2014;4(2):97–104.

Khodzhaeva ZS, Kogan YA, Shmakov RG, Klimenchenko NI, Akatyeva AS, Vavina OV, et al. Clinical and pathogenetic features of early- and late-onset pre-eclampsia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29(18):2980–6.

Strevens H, Wide-Swensson D, Ingemarsson I. Blood pressure during pregnancy in a Swedish population; impact of parity. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2001;80(9):824–9.

Conde-Agudelo A, Belizán JM, Lede R, Bergel EF. What does an elevated mean arterial pressure in the second half of pregnancy predict--gestational hypertension or preeclampsia? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;169(3):509–14.

North RA, McCowan LM, Dekker GA, Poston L, Chan EH, Stewart AW, et al. Clinical risk prediction for pre-eclampsia in nulliparous women: development of model in international prospective cohort. BMJ. 2011;342:d1875.

Gasse C, Boutin A, Coté M, Chaillet N, Bujold E, Demers S. First-trimester mean arterial blood pressure and the risk of preeclampsia: the great obstetrical syndromes (GOS) study. Pregnancy Hypertens. 2018;12:178–182.

van der Tuuk K, Tajik P, Koopmans CM, van den Berg PP, Mol BWJ, van Pampus MG, et al. Blood pressure patterns in women with gestational hypertension or mild preeclampsia at term. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017;210:360–5.

Hermida RC, Ayala DE, Iglesias M. Predictable blood pressure variability in healthy and complicated pregnancies. Hypertension. 2001;38(3 Pt 2):736–41.

Cnossen JS, Vollebregt KC, de Vrieze N, ter Riet G, Mol BW, Franx A, et al. Accuracy of mean arterial pressure and blood pressure measurements in predicting pre-eclampsia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336(7653):1117–20.

Roberts JM, Von Versen-Hoeynck F. Maternal fetal/placental interactions and abnormal pregnancy outcomes. Hypertension. 2007;49(1):15–6.

Myatt L, Roberts JM. Preeclampsia: syndrome or disease? Curr Hypertens Rep. 2015;17(11):83.

Poon LC, Syngelaki A, Akolekar R, Lai J, Nicolaides KH. Combined screening for preeclampsia and small for gestational age at 11-13 weeks. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2013;33(1):16–27.

Tayyar A, Krithinakis K, Wright A, Wright D, Nicolaides KH. Mean arterial pressure at 12, 22, 32 and 36 weeks' gestation in screening for pre-eclampsia. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016;47(5):573–9.

Rolnik DL, Wright D, Poon LC, O'Gorman N, Syngelaki A, de Paco MC, et al. Aspirin versus placebo in pregnancies at high risk for preterm preeclampsia. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(7):613–22.

O'Gorman N, Wright D, Rolnik DL, Nicolaides KH, Poon LC. Study protocol for the randomised controlled trial: combined multimarker screening and randomised patient treatment with ASpirin for evidence-based PREeclampsia prevention (ASPRE). BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e011801.

Nicolaides KH. Turning the pyramid of prenatal care. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2011;29(3):183–96.

Ghi T, Dall'Asta A, Valensise H. Antenatal Care of Preeclampsia: from the inverted pyramid to the arrow model? Fetal Diagn Ther. 2018;44(2):81–84.

Wright A, Wright D, Ispas CA, Poon LC, Nicolaides KH. Mean arterial pressure in the three trimesters of pregnancy: effects of maternal characteristics and medical history. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2015;45(6):698–706.

Roberts JM, Bell MJ. If we know so much about preeclampsia, why haven't we cured the disease? J Reprod Immunol. 2013;99(1–2):1–9.

Acknowledgements

The Preterm SAMBA study group also included: Mary A. Parpinelli, Karayna G Fernandes, José P Guida, Danielly Santana, and Rafael B F Galvao, School of Medical Sciences, University of Campinas, Brazil; Bianca F. Cassettari, School of Medicine of Botucatu, UNESP, Brazil; Lucia Pfitscher, School of Medicine, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil; Daisy Lucena de Feitosa, School of Medicine, Federal University of Ceará, Fortaleza, Brazil; Elias de Melo Ferreira Júnior, Danilo Anacleto, School of Medicine, Federal University of Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil; Vilma Zotareli and Marcia Alice Silva, from Cemicamp. We acknowledge the contribution of all institutions involved in the whole study, including the funders and also the participants who kindly agreed to take part in the full study.

Funding

This study was funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Seatle, WA (grant OPP1107597) and CNPq, Brazil (grant 401636/2013–5). The funders did not influence the study, including development, data collection, data analysis or data interpretation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

The idea for the study arose from JGC, JM, MLC, and PNB. During development of the research proposal, important input was provided by FEF, EARF, JV and IMC from participating centres and from PNB and LCK from the international partnership. After approval, implementation was performed by RTS, JM, DFL, JGC, FEF, EARF, JV and IMC. JM, JGC, MLC and LCK planned this specific analysis. The first draft of the manuscript was prepared by JM. Specific important inputs for the results and the first draft of the protocol were provided by JGC, MLC, PNB and LCK. All authors discussed the results, gave suggestions and agreed to the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is a study derived from the Preterm SAMBA study which obtained ethical approval from the National Committee for Ethics in Research of Brazil (CONEP) and the Committee of Research Ethics (CRE) of the coordinating center, the University of Campinas (Letter of approval 1.048.565 issued on 28th April 2015), and all other Brazilian participating centers: CRE from the Maternidade Escola Assis Chateaubriand of the Federal University of Ceara in Fortaleza, CRE from the Center for Health Sciences of the Federal University of Pernambuco in Recife, CRE from the Clinics Hospital of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul in Porto Alegre, and the CRE from the Clinics Hospital of Botucatu Medical School at the University of the State of Sao Paulo (Unesp). Each woman signed an informed consent form before enrolment in the study. The approval for the study included administrative permissions for the research team to access the data used for this analysis.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Maria L Costa, one of the co-authors is Associate Editor of the BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mayrink, J., Souza, R.T., Feitosa, F.E. et al. Mean arterial blood pressure: potential predictive tool for preeclampsia in a cohort of healthy nulliparous pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 19, 460 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2580-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2580-4