Abstract

A novel theoretical framework for uplink simulations is proposed. It allows investigations which have to cover a very long (real-) time and which at the same time require a certain level of accuracy in terms of radio resource management, quality of service, and mobility. This is of particular importance for simulations of self-organizing networks. For this purpose, conventional system level simulators are not suitable due to slow simulation speeds far beyond real-time. Simpler, snapshot-based tools are lacking the aforementioned accuracy. The runtime improvements are achieved by deriving abstract theoretical models for the MAC layer behavior. The focus in this work is long term evolution, and the most important uplink effects such as fluctuating interference, power control, power limitation, adaptive transmission bandwidth, and control channel limitations are considered. Limitations of the abstract models will be discussed as well. Exemplary results are given at the end to demonstrate the capability of the derived framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

1. Introduction

The requirements for simulation tools are changing with the introduction of novel advanced methods. In particular, investigation of self-organizing networks (SONs) [1–5] have to cover extremely long time intervals; however, they require a sufficient level of accuracy in terms of radio resource management (RRM), quality of service (QoS), and mobility at the same time. For instance, self-optimization of the downtilt angle [6] is a process which may cover at least several days, since the network has to make sure that meaningful statistics on user locations and signal strengths have been collected. Furthermore, there are certainly interactions and collisions between SON and RRM, so that RRM cannot be entirely excluded from the simulations. For instance, if the downtilt angle is changed too fast, RRM measurements might get confused leading to an unstable system. Similar things hold for other SON use cases such as load balancing [7], mobility robustness optimization, and automatic neighbor relation [5].

Typical system-level simulations [8] have a very exact implementation of RRM and QoS by explicitly modeling all the fast decisions, typically on a millisecond time scale or even below, for example [9]. This ends up in a very large simulation runtime, far beyond real-time. Simulating several hours, days, or even more is impossible with this class of simulators. Those simulators are used to make accurate performance evaluations given a fixed parameter configuration according to specified reference scenarios.

Alternatively, the use of light, snapshot-based tools is quite popular [10, 11]. Those allow for a rapid collection of network statistics. However, accuracy of RRM and QoS is lost to a wide extent. In particular, handover effects such as hysteresis and time to trigger. can not be modeled without having a true time axis implemented. Furthermore, traffic characteristics are poorly reflected, for example, the fact that users at the cell edge require much more resources than close users in many cases. It is also more than critical to investigate convergence behavior of dynamic SON loops without a real-time axis and without real mobility. Those simulators are used for network planning or for coarse studies to understand the interrelations of new features, for example, heterogeneous networks [12].

In this work we will present the theoretical framework for a new class of simulators which is capable of making very long SON simulations with the necessary level of accuracy. It can be understood as a smart extension of snapshot-based tools with a time axis and with abstract, semianalytical models of RRM and QoS. It allows self-tuning of parameters during the simulations (which is a typical SON aspect) rather than using a fixed parameter configuration for every simulation. We are certainly not reaching the accuracy of full system-level simulations; however, this is not needed in many cases. For the downlink this work has already been started in [13]. Unfortunately the uplink shows a lot of fundamental differences compared with the downlink which complicates mattersin the following way.

-

(i)

Every terminal has its own individual power budget.

-

(ii)

The uplink typically has a power control (due to near/far problem).

-

(iii)

The intercell interference is heavily fluctuating.

-

(iv)

Control channel limitations are more critical.

-

(v)

The access scheme might be different so that the scheduling strategies are different.

Those aspects will be addressed in this work based on the principles introduced in [13]. Although the focus of this work is on the introduction of the simulation framework, we will also give some calibration results as well as some first SON results. The derivations are based on the 3GPP standard long-term evolution (LTE) [14]. However the principles can be applied to other systems such as HSPA and WiMAX as well.

We will start with definitions of the LTE uplink, the uplink power control, and the uplink SINR. In Section 3 we will discuss the scheduling strategies. We will consider different resource fair strategies, throughput fair strategies and QoS strategies targeting a certain bit rate. All derivations are done under the assumption of anadaptive transmission bandwidth scheduler. Performance metrics are introduced in Section 4, in particular, dissatisfaction levels due to overload, power limitation, and control channel limitation. Results with the new framework are given in Section 5, and Section 6 concludes this work. In the appendices important and interesting properties of fairness in the uplink in comparison to downlink fairness are discussed.

2. Definitions

We will discuss the LTE uplink, which is a Single Carrier FDMA system. [14]. The whole system bandwidth is divided into  subbands which are called physical resource blocks (PRBs). In every transmission time interval (TTI) a user can be assigned a subset of those

subbands which are called physical resource blocks (PRBs). In every transmission time interval (TTI) a user can be assigned a subset of those  PRBs which, however, have to be adjacent. The user will spread the symbols to transmit over this group of PRBs. Note that this so-called single carrier constraint is different to the OFDMA downlink.

PRBs which, however, have to be adjacent. The user will spread the symbols to transmit over this group of PRBs. Note that this so-called single carrier constraint is different to the OFDMA downlink.

Due to the single carrier constraint a frequency selective scheduler for the LTE uplink may have a packing problem ("Tetris" problem), that is, it might not be able to fill the entire bandwidth in some cases. The more multiuser diversity the scheduler aims to exploit, the larger will be the packing problem. In this work we neglect those cutaways, that is, we assume that the scheduler can fill the entire bandwidth. Note that it is very easy to construct such a scheduler, but the frequency-selective multi-user gain will be poor.

Random variables will be written in bold letters, for example,  or

or  . It is very important for this work to distinguish between random and deterministic variables. All variables refer to linear values, except the first equations (1) to (4) that make use of the dB domain. For the sake of better notation we are using the same symbols nevertheless.

. It is very important for this work to distinguish between random and deterministic variables. All variables refer to linear values, except the first equations (1) to (4) that make use of the dB domain. For the sake of better notation we are using the same symbols nevertheless.

2.1. General Definitions

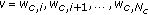

We are assuming a network given by  users

users  located at the coordinates

located at the coordinates  , and

, and  cells

cells  . All propagation effects (comprising pathloss, antenna patterns, and shadowing) between position

. All propagation effects (comprising pathloss, antenna patterns, and shadowing) between position  and cell

and cell  are summarized in the propagation maps

are summarized in the propagation maps . Details on the included propagation effects are found in [13]. Note that the propagation maps are deterministic for our investigations even if the shadowing has been generated randomly. Fast Fading is not considered in this work.

. Details on the included propagation effects are found in [13]. Note that the propagation maps are deterministic for our investigations even if the shadowing has been generated randomly. Fast Fading is not considered in this work.  is the thermal noise on a single PRB.

is the thermal noise on a single PRB.

is the downtilt angle of cell

is the downtilt angle of cell  . We assume that this is the only propagation parameter which can be dynamically influenced, all others are either given by the environment (e.g., pathloss exponent, shadowing) or are configured statically (e.g., antenna height, azimuth orientation) and are therefore omitted. Please note that downtilt optimization is an important SON use case, and hence we leave the downtilt angle in the equations although we do not present results on that.

. We assume that this is the only propagation parameter which can be dynamically influenced, all others are either given by the environment (e.g., pathloss exponent, shadowing) or are configured statically (e.g., antenna height, azimuth orientation) and are therefore omitted. Please note that downtilt optimization is an important SON use case, and hence we leave the downtilt angle in the equations although we do not present results on that.

Furthermore, every cell  can adjust individual power control settings given by the parameters

can adjust individual power control settings given by the parameters  and

and  according to [15]. We assume that user

according to [15]. We assume that user  is served by cell

is served by cell  , where

, where  is theconnection function, and every user is connected exactly to a single cell. In this work, we assume that

is theconnection function, and every user is connected exactly to a single cell. In this work, we assume that  is given by the best serving cell on downlink, that is, every user is connected to the strongest cell. This is a typical case; however we could in principle also optimize the connection function with the equations given in this work.

is given by the best serving cell on downlink, that is, every user is connected to the strongest cell. This is a typical case; however we could in principle also optimize the connection function with the equations given in this work.

The number of users in cell  is abbreviated by

is abbreviated by  , and the set of users connected to cell

, and the set of users connected to cell  is abbreviated by

is abbreviated by  .

.

2.2. Power Control

Uplink Power Control is typically given by the equation (cf. [15], neglecting the closed loop terms)

where  is the total transmit power of user

is the total transmit power of user  ,

,  is the maximum transmit power, and

is the maximum transmit power, and  is the number of PRBs allocated to user

is the number of PRBs allocated to user  . In the following we will use the transmit power per PRB

. In the following we will use the transmit power per PRB  instead of the total transmit power

instead of the total transmit power  . Furthermore, we assume that the scheduler at the serving cell

. Furthermore, we assume that the scheduler at the serving cell  is smart enough that it will not drive users into power limitation through the choice of

is smart enough that it will not drive users into power limitation through the choice of  , that is it will limit the number of PRBs

, that is it will limit the number of PRBs  such that the

such that the  operator does not expire (the

operator does not expire (the  operator can only expire for

operator can only expire for  ). This behavior will be elaborated later on in Section 3.2. In this case we can define the transmit power per PRB (actually power spectral density) as

). This behavior will be elaborated later on in Section 3.2. In this case we can define the transmit power per PRB (actually power spectral density) as

2.3. Signal-to-Noise and Interference Ratio

With this definition, we can write the received power of user  at its serving cell

at its serving cell  as (we are omitting the superscript

as (we are omitting the superscript  for the following variables although we keep on using spectral densities/power per PRB)

for the following variables although we keep on using spectral densities/power per PRB)

Similarly, we define the interference produced by user  at any other cell

at any other cell  as

as

Note that this interference is only produced if user  is scheduled by its serving cell

is scheduled by its serving cell  at the time and PRB of interest. Let us define the random variable

at the time and PRB of interest. Let us define the random variable  which specifies the user which is scheduled by cell

which specifies the user which is scheduled by cell  at a particular time and a particular PRB. We call the probability that cell

at a particular time and a particular PRB. We call the probability that cell  schedules user

schedules user  the scheduling probabilities

the scheduling probabilities . We assume that the scheduling probabilities are identically distributed over time and frequency but not independently. Correlations and further details of the random variables

. We assume that the scheduling probabilities are identically distributed over time and frequency but not independently. Correlations and further details of the random variables  will be discussed later on. As a consequence, the interference produced from cell

will be discussed later on. As a consequence, the interference produced from cell  to a target cell

to a target cell  is also a random variable:

is also a random variable:

Furthermore the SINR for user  also gets a random variable (although we ignore fast fading at all):

also gets a random variable (although we ignore fast fading at all):

Note that whereas we have used power values in dB so far, any power and SINR variables in this and the following equations are linear values (using the same symbols). In the following we will look at the average of this random SINR (still on a per user basis):

Let us make some important observations.

-

(i)

The received power

is not a random variable.

is not a random variable. -

(ii)

The last expectation of (7) does not depend on user

, only on the cell

, only on the cell  , that is, it is the same for all other users connected to cell

, that is, it is the same for all other users connected to cell  .

. -

(iii)

It is interesting to see that the more the interference

fluctuates, the smaller gets the average SINR. This is easily derived from Jensen's inequality (

fluctuates, the smaller gets the average SINR. This is easily derived from Jensen's inequality ( is a convex function).

is a convex function).

Note that the random variable  is actually a deterministic function of the random variable

is actually a deterministic function of the random variable  (cf. (5)),that is, the interference is determined as soon as the scheduler has selected a user

(cf. (5)),that is, the interference is determined as soon as the scheduler has selected a user  .

.

2.4. Evaluation of the Expectation

Even if we already knew the scheduling probabilities  , the expectation would be very inconvenient to evaluate. In this section, we assume that the scheduling probabilities are well known (we will discuss later on how to calculate them), and we will focus on the evaluation of the expectation in the average SINR expression (7). We have observed that this expectation is cell specific and does not depend on the user, so we have replaced

, the expectation would be very inconvenient to evaluate. In this section, we assume that the scheduling probabilities are well known (we will discuss later on how to calculate them), and we will focus on the evaluation of the expectation in the average SINR expression (7). We have observed that this expectation is cell specific and does not depend on the user, so we have replaced  directly by cell

directly by cell  :

:

Obviously, this expectation is multidimensional, since  different (independent) random variables

different (independent) random variables  's are involved. We can give a closed-form expression:

's are involved. We can give a closed-form expression:

Please note that cell  does not contribute to the interference on itself. However, for the sake of better illustration we have left the corresponding sum in the equation. Unfortunately, the nested sum can hardly be evaluated numerically. For instance, in a typical scenario [16] with 57 cells and 10 users per cell we would have

does not contribute to the interference on itself. However, for the sake of better illustration we have left the corresponding sum in the equation. Unfortunately, the nested sum can hardly be evaluated numerically. For instance, in a typical scenario [16] with 57 cells and 10 users per cell we would have  addends. Unfortunately, due to the nonlinearity of the

addends. Unfortunately, due to the nonlinearity of the  function, there is no way to separate the random variables and thereby the nested sums. Restricting the interference impact to only close neighbors (e.g., first and second ring around a cell) reduces the problem a bit; however it is still hardly feasible. Note that we have used the abbreviation

function, there is no way to separate the random variables and thereby the nested sums. Restricting the interference impact to only close neighbors (e.g., first and second ring around a cell) reduces the problem a bit; however it is still hardly feasible. Note that we have used the abbreviation  which is the set of users connected to cell

which is the set of users connected to cell  .

.

A practical solution is a Monte Carlo integration. We generate a large number  of random

of random  - tuples

- tuples  with

with containing samples of the random variables

containing samples of the random variables  . As long as the number of samples

. As long as the number of samples  is sufficiently large, we can get a good approximation of the expectation by

is sufficiently large, we can get a good approximation of the expectation by

Our investigations have shown that  gives stable results and is still feasible from a complexity point of view. Note that for the Monte Carlo approach the generation of the random

gives stable results and is still feasible from a complexity point of view. Note that for the Monte Carlo approach the generation of the random  -tuples certainly must follow the scheduling probabilities

-tuples certainly must follow the scheduling probabilities  . Accuracy can be increased by combining the two approaches: the first ring of interfering cells can be exactly evaluated whereas the rest of the cells is considered by the Monte Carlo approach. In this paper we have only used the Monte-Carlo approach.

. Accuracy can be increased by combining the two approaches: the first ring of interfering cells can be exactly evaluated whereas the rest of the cells is considered by the Monte Carlo approach. In this paper we have only used the Monte-Carlo approach.

2.5. Rate Function

Using the previously derived  (per PRB) we define a rate function

(per PRB) we define a rate function  to be the data rate which a user can achieve on a single PRB with average

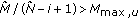

to be the data rate which a user can achieve on a single PRB with average  using an appropriate modulation and coding scheme. In the simplest case we could use Shannon's capacity equation or an extension thereof. In this work, we will follow a more realistic approach using link level results. We are using an abstract model presented in [17] which has been shown to be very close to real simulations using the Turbo codes defined in 3GPP [14]. The LTE uplink overhead through reference signals has been taken into account. Figure 1 shows the employed rate function including the Shannon reference with and without considering the LTE overhead.

using an appropriate modulation and coding scheme. In the simplest case we could use Shannon's capacity equation or an extension thereof. In this work, we will follow a more realistic approach using link level results. We are using an abstract model presented in [17] which has been shown to be very close to real simulations using the Turbo codes defined in 3GPP [14]. The LTE uplink overhead through reference signals has been taken into account. Figure 1 shows the employed rate function including the Shannon reference with and without considering the LTE overhead.

Note that the Shannon bounds inherently assume a perfect selection of modulation and coding schemes. However in the uplink, due to fluctuating interference, this selection can not be perfect by definition, even not in static channel conditions. Furthermore imperfect channel estimation will also degrade the performance. The consequence is a loss of some dBs. On the other hand, the base stations typically have 2 receive antennas, which is also not considered in the Shannon bounds which will lead to a gain in the range of 3 dB. Furthermore, frequency selective scheduling (e.g., though proportional fair scheduling) will lead to multi-user diversity gain [18, 19].

In this work we will assume that those effects will compensate each other such that the rate function used here (red solid curve) is rather close to the Shannon bound considering the overhead through cyclic prefix and reference signals. Later on in Section 5.2 we will see that this assumption leads to a good agreement with existing simulation results.

3. Scheduling Probabilities

Let us now have a closer look at the scheduling probabilities  . We will consider several scheduler strategies. Note that the random variable

. We will consider several scheduler strategies. Note that the random variable  is discrete; it can adopt values

is discrete; it can adopt values  with the probability

with the probability  . For mathematical correctness, we need to define a kind of idle value, for example,

. For mathematical correctness, we need to define a kind of idle value, for example,  , with nonzero probability

, with nonzero probability  which represents the case that no user is scheduled in cell

which represents the case that no user is scheduled in cell  (at the considered time and frequency, that is, a PRB is left empty). All other values have the probability

(at the considered time and frequency, that is, a PRB is left empty). All other values have the probability  . With these definitions, we can write (just for comprehension)

. With these definitions, we can write (just for comprehension)

3.1. General Expression

Let us define the average number of PRBs  which is allocated to user

which is allocated to user  . Note that

. Note that  . Given all

. Given all  's in cell

's in cell  , we can write the scheduling probabilities as

, we can write the scheduling probabilities as

We observe that the scheduling probabilities depend purely on the average number of assigned PRBs  's. Hence, we will investigate those elaborately in the following sections. We will be looking at individual cells; we assume that cells in general behave independently, that is, the random variables

's. Hence, we will investigate those elaborately in the following sections. We will be looking at individual cells; we assume that cells in general behave independently, that is, the random variables  's are mutually independent, too.

's are mutually independent, too.

3.2. Adaptive Transmission Bandwidth

The key difference compared with the downlink is the fact that every user has an individual power budget in the uplink. So we can shift PRBs from one user to another, but not power. As a direct consequence, the maximum number of PRBs which can be given to a user without driving it into power limitation depends on the difference between transmit power per PRB  (given by (2)) and the maximum transmit power

(given by (2)) and the maximum transmit power  which is typically called power headroom:

which is typically called power headroom:

An uplink scheduler should never assign a user more PRBs than this limit  . Otherwise, looking at the original power control equation (1), we observe that the users would have to spread the same power over the assigned PRBs instead of increasing the power with every assigned PRB (the

. Otherwise, looking at the original power control equation (1), we observe that the users would have to spread the same power over the assigned PRBs instead of increasing the power with every assigned PRB (the  operator in the PC equation (1) expires). This results in an SINR loss which would eat up at least part of the bandwidth gain. Furthermore, other (non-power-limited) users can make much better use of the bandwidth. Finally, spreading the maximum power over several PRBs would increase the dynamic range problems. Note that for the PC equation per PRB (2) we have already inherently assumed that the scheduler does not exceed the aforementioned limit. This behavior is typically called adaptive transmission bandwidth [ 20 ].

operator in the PC equation (1) expires). This results in an SINR loss which would eat up at least part of the bandwidth gain. Furthermore, other (non-power-limited) users can make much better use of the bandwidth. Finally, spreading the maximum power over several PRBs would increase the dynamic range problems. Note that for the PC equation per PRB (2) we have already inherently assumed that the scheduler does not exceed the aforementioned limit. This behavior is typically called adaptive transmission bandwidth [ 20 ].

Obviously this limits the maximum average number of PRBs as well, since every user can be scheduled at maximum in every time slot, hence we have

3.3. Strict Resource Fair

The straightforward definition of the resource fair scheduler would be that the  users in cell

users in cell  share the available resources, that is,

share the available resources, that is,  . However, this may violate the power limitation of the UEs in (14). If we require resource fairness, nevertheless, that is,

. However, this may violate the power limitation of the UEs in (14). If we require resource fairness, nevertheless, that is,  should be the same for all users, then every user can only get as many PRBs as the worst user (using the highest transmit power). We can write

should be the same for all users, then every user can only get as many PRBs as the worst user (using the highest transmit power). We can write

An important observation is that this solution is also throughput fair in the case of  (with the exception that power limited users would have smaller throughput). Otherwise (

(with the exception that power limited users would have smaller throughput). Otherwise ( ) close users get higher throughput since the received power is higher and the interference is the same for all users in a cell.

) close users get higher throughput since the received power is higher and the interference is the same for all users in a cell.

3.4. Modified Resource Fair

The previous scheduler has the disadvantage that it may leave a lot of resources unused although close users would still be able to extend their bandwidth. Unfortunately, users at the cell edge with high propagation loss cannot make use of the spare bandwidth due to power limitation.

In another extreme solution we could try to always give every user  its maximum allowed bandwidth

its maximum allowed bandwidth  . If this does not exceed the available resources, that is,

. If this does not exceed the available resources, that is,  , this is a viable approach. However, this will be relatively unlikely in reality since already a single close user could have enough transmit power to occupy more than

, this is a viable approach. However, this will be relatively unlikely in reality since already a single close user could have enough transmit power to occupy more than  PRBs.

PRBs.

In this case we need to scale down the number of PRBs. The simplest solution would scale down all  's in the same way. However this would leave too much unfairness in the system. Instead we prefer scaling down large

's in the same way. However this would leave too much unfairness in the system. Instead we prefer scaling down large  's and bring this new solution as close as possible to the resource fair case. We will call this solution modified resource fair although it is in general not resource fair. However, in annex A we will observe that this solution achieves the same fairness as the typical resource fair definition in the downlink.

's and bring this new solution as close as possible to the resource fair case. We will call this solution modified resource fair although it is in general not resource fair. However, in annex A we will observe that this solution achieves the same fairness as the typical resource fair definition in the downlink.

We propose a simple iterative method which starts with the previous resource fair case. We define the indices  such that they address all users

such that they address all users  in cell

in cell  in ascending order with respect to

in ascending order with respect to  's, that is,

's, that is,  addresses the worst user in cell

addresses the worst user in cell  ,

,  addresses the second worst user, and so forth. We will formulate our algorithm as follows:

addresses the second worst user, and so forth. We will formulate our algorithm as follows:

-

(1)

Initialize:

;

;

-

(2)

Abbreviate

-

(3)

if

-

(a)

-

(b)

else

else -

(c)

for all

for all

-

(d)

exit

-

(a)

-

(4)

Increment

and go to step 2

and go to step 2

In every iteration, we check whether the remaining resource budget  equally shared among the remaining

equally shared among the remaining  exceeds the PRB limit

exceeds the PRB limit  of the worst of the remaining users

of the worst of the remaining users  . If yes, the worst remaining user gets its maximum number of PRBs

. If yes, the worst remaining user gets its maximum number of PRBs  , and we assign the remaining budget in the next iteration. Otherwise the remaining budget is equally shared among the remaining users, and we exit the algorithm.

, and we assign the remaining budget in the next iteration. Otherwise the remaining budget is equally shared among the remaining users, and we exit the algorithm.

Note again that in this solution the worst user gets the least amount of resources, but the maximum it can afford. With a high number of users this case will converge against the previous "Resource Fair" case.

3.5. Throughput Fair

In this section we try to approximate a throughput fair solution. We have already mentioned that the number of PRBs is limited for the users. Since the interference is the same for all users the throughput achievable by all users is determined by the worst user (in particular for  ). The true throughput fair solution employs the rate function and writes as

). The true throughput fair solution employs the rate function and writes as

for two users  and

and  in the same cell. Note that throughput fairness is required per cell. Unfortunately the SINRs are not known so far; recall that the

in the same cell. Note that throughput fairness is required per cell. Unfortunately the SINRs are not known so far; recall that the  's are needed to calculated scheduling probabilities and thereby the SINRs. Therefore we will give two different approximations in the following.

's are needed to calculated scheduling probabilities and thereby the SINRs. Therefore we will give two different approximations in the following.

As a first approximation, we will do the simplifying assumption that the throughput is proportional to the SINR, that is, we assume linear rate function. From (7) we observe that the average SINR of a user within a certain cell is proportional to the received power (since the interference is cell specific). In this case the throughput fair criterion of the previous equation degenerates to

Another approximation which is derived from Shannon's equation is

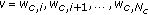

The comparison of the two approximations is shown in Figure 2 where we have used  . The true relation obviously depends on the SINR range of the reference user (cf. legend). The linear approximation fits for very small SINR ranges; the

. The true relation obviously depends on the SINR range of the reference user (cf. legend). The linear approximation fits for very small SINR ranges; the  approximation fits better for medium SINR ranges.

approximation fits better for medium SINR ranges.

Both approximations have the very nice property that they only depend on the positions of the users within a cell and not on intercell interference or other cells in general. With those assumptions, we can formulate the throughput fair (approximated) solution in three steps.

First we assume that the worst user gets the maximum number of PRBs:

Next we derive the number of PRBs for all the other users in the cell by applying equation (17)

or (18)

Finally we need to check whether we have exceeded the resource limit. In this case, we have to scale down all  's by the same factor in order to fit into the available resources whilst maintaining the throughput fairness:

's by the same factor in order to fit into the available resources whilst maintaining the throughput fairness:

3.6. Quality of Service

A drawback of the previous methods is that we cannot define a target QoS or a user satisfaction level. Inherently the methods were based on the best effort and full buffer assumption. The users always have data to transmit on one hand; on the other hand they do not have to meet a certain target, that is, they are satisfied with whatever resources  they get.

they get.

For a variety of services a certain QoS target has to be met. For instance, users are only satisfied if they get a certain bit rate  . If they get less, they are unsatisfied. On the other hand, they typically cannot transmit more than

. If they get less, they are unsatisfied. On the other hand, they typically cannot transmit more than  , so the system will assign only the resources

, so the system will assign only the resources  such that the target rate is fulfilled, not more. Such a behavior is called constant bit rate(CBR) service.

such that the target rate is fulfilled, not more. Such a behavior is called constant bit rate(CBR) service.

Initially, let us assume that the SINRs are already known. We will resolve this assumption in the subsequent section. The approach is very similar to the approach in [13]. In order to achieve the target rate  whilst observing the power (and therefore resource) limitation in uplink, we write the required average number of PRBs for user

whilst observing the power (and therefore resource) limitation in uplink, we write the required average number of PRBs for user  as

as

where  is the rate function introduced in Section 2.5. It is important to observe that a user cannot be satisfied if the

is the rate function introduced in Section 2.5. It is important to observe that a user cannot be satisfied if the  operator expires, irrespective of the traffic situation in the own cell (even if the user were alone). The only way to improve those users is to decrease the intercell interference, which requires modifications in the neighboring cell such as decreasing the P0 [21]. Note that any of those modifications is likely to reduce the QoS level in the neighboring cell.

operator expires, irrespective of the traffic situation in the own cell (even if the user were alone). The only way to improve those users is to decrease the intercell interference, which requires modifications in the neighboring cell such as decreasing the P0 [21]. Note that any of those modifications is likely to reduce the QoS level in the neighboring cell.

A cell can be defined in overload if the sum of the required resources exceeds the available resources,  . In this case contention control would drop some users (or, equivalently, admission control would not even have admitted some users). We assume that those control mechanisms work arbitrarily, that is, they do not prefer some (e.g., close) users and discriminate others (e.g., far users). This case can be modeled by applying the same scaling procedure as in (22):

. In this case contention control would drop some users (or, equivalently, admission control would not even have admitted some users). We assume that those control mechanisms work arbitrarily, that is, they do not prefer some (e.g., close) users and discriminate others (e.g., far users). This case can be modeled by applying the same scaling procedure as in (22):

This scaling procedure would basically make every user unsatisfied. However note that the scheduling probabilities here are needed to calculate SINRs. Performance metrics will be discussed in Section 4. Alternatively, we could make use of admission control functionality here, which basically would select a subset  (and drops the other users) such that

(and drops the other users) such that  is fulfilled.

is fulfilled.

We would like to emphasize again that we have assumed that the  's are already known. However, we actually need the scheduling probabilities to calculate the

's are already known. However, we actually need the scheduling probabilities to calculate the  's based on (7). So in contrast to the strict resource fair, modified resource fair and (approximated) throughput fair solutions of the previous sections, we unfortunately have not found a closed form solution for the QoS case. This problem is very similar to the downlink problem as described in [13].

's based on (7). So in contrast to the strict resource fair, modified resource fair and (approximated) throughput fair solutions of the previous sections, we unfortunately have not found a closed form solution for the QoS case. This problem is very similar to the downlink problem as described in [13].

3.7. Comparison with Real-World Schedulers

In the following we will discuss how real schedulers would map to the previously introduced strategies. The most popular scheduler is a proportional fair(PF) scheduler. The pure PF strategy is resource fair [18, 19]. However, unfortunately the PF definition in the uplink is not as straightforward as it is in the downlink due to power control and power limitation. Most of the uplink PF strategies in LTE will use adaptive transmission bandwidth and will be very close to the modified resource fair definition introduced in Section 3.4, when assuming full buffer/best effort traffic models (i.e., no further QoS constraints), compare, for example, [20]. Note that the scheduling gain, that is, the fact that the SINR conditioned on a user being scheduled gets better, goes into the throughput mapping discussed in Section 2.5 and not into the scheduling probabilities. Hence, PF and round robin strategies are equivalent from the perspective of scheduling probabilities (both are resource fair).

Furthermore, the PF strategies typically have to be extended with QoS constraints such as a target bit rate, minimum bit rate, or delay constraints. Those extended PF versions will come closer to the QoS scheduler described in Section 3.6. Once again, the reduced scheduling gain (through more QoS constraints) is considered in the throughput mapping, rather than in the scheduling probabilities.

3.8. Initialization of the SINRs

In this section we will propose 2 different solutions. Let us first recall the SINR definition from (7)

The first observation is that the abbreviated expectation  is only cell specific and not user specific. Hence, for a first guess of the

is only cell specific and not user specific. Hence, for a first guess of the  's according to (23) and (24), we only need to approximate a single value rather than

's according to (23) and (24), we only need to approximate a single value rather than  user-specific

user-specific  's, which seems to be a much simpler problem. If we are applying the framework in this paper to a dynamic simulator with a continuous time axis, we can simply take the guess of the expectation from the previous time step. Similarly, we can read that once we know the

's, which seems to be a much simpler problem. If we are applying the framework in this paper to a dynamic simulator with a continuous time axis, we can simply take the guess of the expectation from the previous time step. Similarly, we can read that once we know the  of one user

of one user  (e.g., the worst user), we know all the others by the simple relation

(e.g., the worst user), we know all the others by the simple relation

The advantage is that it might be easier to make a guess on the SINR since it is a relative number rather than a guess on the expectation which is an absolute number. In particular the SINR of the worst user in a cell is rather likely to be very small. So the second proposal is to set the SINR of the worst user in every cell to a predefined value  (e.g., 0 dB), and the other user's SINR in the same cell are derived from that according to (26). This method has the advantage that it also works with so-called snapshot- like simulators which do not have a time axis. In a dynamic simulator, this approach is probably less accurate than the first one.

(e.g., 0 dB), and the other user's SINR in the same cell are derived from that according to (26). This method has the advantage that it also works with so-called snapshot- like simulators which do not have a time axis. In a dynamic simulator, this approach is probably less accurate than the first one.

4. Performance Metrics

So far, we have an (almost) analytical expression  for the average SINR of every user in an LTE uplink network. Furthermore, we have already discussed the average number

for the average SINR of every user in an LTE uplink network. Furthermore, we have already discussed the average number  of assigned PRBs for different scheduling strategies. Note that in the QoS case the

of assigned PRBs for different scheduling strategies. Note that in the QoS case the  's actually depend on the SINRs which are not known when calculating the

's actually depend on the SINRs which are not known when calculating the  's. Hence, before calculating performance metrics we should update the

's. Hence, before calculating performance metrics we should update the  's with the more accurate values of the SINRs.

's with the more accurate values of the SINRs.

From these  's and

's and  's we now can start deriving several capacity metrics such as average cell throughput, throughput percentiles, or number of (un)satisfied users.

's we now can start deriving several capacity metrics such as average cell throughput, throughput percentiles, or number of (un)satisfied users.

4.1. Throughput Metrics

In the simplest case, we calculate the user throughputs as

From those rates we can calculate a total network throughput, throughputs per cell, or throughput percentiles. In principle we could also check whether users are satisfied by comparing their data rates with the rate requirements  's. However recall that in (24) we have scaled down the

's. However recall that in (24) we have scaled down the  's of all users in case of an overload. In this case, all users would fall below their

's of all users in case of an overload. In this case, all users would fall below their  's although in reality it might be sufficient to drop very few users to make the rest satisfied again. Furthermore, it would be interesting to have a quantitative notion of how much overloaded a cell is and how many users are unsatisfied in fact. So for the QoS case, we will define more appropriate performance metric in the following.

's although in reality it might be sufficient to drop very few users to make the rest satisfied again. Furthermore, it would be interesting to have a quantitative notion of how much overloaded a cell is and how many users are unsatisfied in fact. So for the QoS case, we will define more appropriate performance metric in the following.

4.2. Overload and Unsatisfied Users

Exactly as in [13] we return to the required number of PRBs from (23) and define a virtual cell load

which can exceed 1 thereby indicating the degree of overload. For instance,  means a 10% overloaded cell, and

means a 10% overloaded cell, and  means that the cell is double overloaded, that is, half of the users will be unsatisfied. Again assuming that an admission/contention control would exclude arbitrary users (not preferably cell edge users), we can write the number of unsatisfied users in cell

means that the cell is double overloaded, that is, half of the users will be unsatisfied. Again assuming that an admission/contention control would exclude arbitrary users (not preferably cell edge users), we can write the number of unsatisfied users in cell  as

as

This number accounts for dissatisfaction through overload. In addition, we will also have unsatisfied users through power limitation as already discussed in the context of (23), even if the virtual load is very small. We simply count their number in cell

where  returns the size of the set

returns the size of the set  . A further limitation on cell level is given by the fact that the number of users which can be scheduled at the same time is constrained by the available resources for control channels (physical downlink control channel PDCCH in LTE). Note that this can be a painful restriction in particular in the uplink, where the individual UE power budgets limit the ability of following an aggressive TDMA strategy. With our mathematical framework we can easily capture this limitation as well. Assume that the maximum number of schedulable users in cell

. A further limitation on cell level is given by the fact that the number of users which can be scheduled at the same time is constrained by the available resources for control channels (physical downlink control channel PDCCH in LTE). Note that this can be a painful restriction in particular in the uplink, where the individual UE power budgets limit the ability of following an aggressive TDMA strategy. With our mathematical framework we can easily capture this limitation as well. Assume that the maximum number of schedulable users in cell  per TTI is given by

per TTI is given by  . (This is a simplification. In LTE this is not a hard limit, but it depends on the user positions.) The control channel consumption is minimized by a scheduling strategy which would always assign the maximum number of resources

. (This is a simplification. In LTE this is not a hard limit, but it depends on the user positions.) The control channel consumption is minimized by a scheduling strategy which would always assign the maximum number of resources  according to (13) to a scheduled user. This maximized the number of TTIs in which a user is not scheduled, that is, where it does not require any control resources. Hence, the (averaged) minimum number of required control channels required by user

according to (13) to a scheduled user. This maximized the number of TTIs in which a user is not scheduled, that is, where it does not require any control resources. Hence, the (averaged) minimum number of required control channels required by user  per TTI is

per TTI is

using the required number of PRBs  from (23). Note that

from (23). Note that  . Obviously, the control channels will definitely (even without any delay requirement) cause dissatisfaction in case

. Obviously, the control channels will definitely (even without any delay requirement) cause dissatisfaction in case

Equivalent to the load dissatisfaction we will again assume that admission/contention control would exclude arbitrary users and thus we can define the number of unsatisfied users due to control channel limitation as

Finally we have to combine the three metrics  ,

,  , and

, and  to a single number of unsatisfied users per cell. With our high level of abstraction this is quite challenging since the sets of load-, power-, and control-unsatisfied users might be overlapping. A heuristic approach would exclude users one by one (power-limited users first) and recalculate the metrics until dissatisfaction has disappeared. Another approach exploits the intuitive fact that the set of load- and control-limited users (i.e., the cell level metrics) are obviously fully overlapping. The set of power-limited users (user-level metric) will be rather disjoint. With those assumptions we approximate the total number of unsatisfied users in cell

to a single number of unsatisfied users per cell. With our high level of abstraction this is quite challenging since the sets of load-, power-, and control-unsatisfied users might be overlapping. A heuristic approach would exclude users one by one (power-limited users first) and recalculate the metrics until dissatisfaction has disappeared. Another approach exploits the intuitive fact that the set of load- and control-limited users (i.e., the cell level metrics) are obviously fully overlapping. The set of power-limited users (user-level metric) will be rather disjoint. With those assumptions we approximate the total number of unsatisfied users in cell  as

as

5. Results

A dynamic system level simulator has been implemented based on the derivations in the previous chapters. In this section we will present some results with standard assumptions (such as full buffer traffic, proportional fair scheduler), and we will show that those are very close to other simulation results which have been agreed for by several companies in [9, 22]. Furthermore, we will present results with CBR traffic, and we will also look at an irregular network with SON adaptation of the power control parameters. Finally we will elaborate on the huge runtime performance.

5.1. Simulation Assumptions

We will use standard assumptions as proposed in [16], comprising a network of 19 LTE base stations with an intersite distance of 500 m, serving 57 hexagonal cells (sectors). Pathloss law, shadowing model, and horizontal beam pattern are also taken from [16], a vertical pattern is not used. The users are moving with a speed of 3 km/h, and they are handover to another cell if the received signal strength (measured on downlink reference signals) with respect to the new cell is 3 dB better than that with respect to the serving cell (handover hysteresis). One simulation step is 100 ms, that is, the network performance is evaluated 10 times a second.

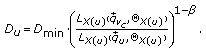

We are using homogeneous P0 values of  or

or  and a homogeneous

and a homogeneous  value of

value of  . The resulting distribution of transmit power per PRB is shown in Figure 3. Note that this distribution does not depend on the scheduling mechanism or traffic model since we record one power value for every user per simulation step.

. The resulting distribution of transmit power per PRB is shown in Figure 3. Note that this distribution does not depend on the scheduling mechanism or traffic model since we record one power value for every user per simulation step.

It is obvious that the larger P0 setting of  52 dBm leads to higher transmit powers. In this case we can also identify the maximum transmit power of 23 dBm.

52 dBm leads to higher transmit powers. In this case we can also identify the maximum transmit power of 23 dBm.

5.2. Full Buffer Traffic

We will start with the simple assumption of a full buffer traffic model and a modified resource fair scheduler as presented in Section 3.4. Users are uniformly dropped into the network area such that every cell serves an average of 10 users. The distribution of the user throughputs according to (27) is given in Figure 4.

As expected we observe slightly higher user throughputs with the larger P0 value. However, the difference between the curves is smaller in the lower part of the plot, since the power limitation is more critical with the smaller P0 value. The 5% percentiles (which is typically referred to as cell edge throughput) are420 kbps and503 kbps whereas the average cell throughputs are 7.3 Mbps and 8.5 Mbps, respectively. This is in very good agreement with the simulations in [9, 22]. The results of different companies are compared in [22] for the reference case which we have used as well. The cell throughput results are in the range between 6.3 Mbps and 1.01 Mbps, with an average of 8.6 Mbps (which is also the result of [9]). The cell edge results span from 100 kbps to 460 kbps with an average of 260 kbps. Obviously our results are a bit too optimistic in terms of cell edge throughput which could be a consequence of the neglected fast fading, and, even more important, of handover gain, which is included in our simulations with full mobility.

5.3. Constant Bit Rate Traffic

Next we will assume a constant bit rate traffic model and a QoS scheduler as presented in Section 3.6. Different target data rates are assumed, namely, 96 kbps, 256 kbps, and 512 kbps. Again, users are uniformly dropped into the network; however, the average number of users per cell is varied from 5 to 80. Let us first look at the percentage of unsatisfied users due to power limitation  as given by expression (30) in Figure 5.

as given by expression (30) in Figure 5.

We observe the following behavior.

-

(i)

All curves reach a maximum and then do not grow any further. The reason is that the actual load is limited and cannot exceed 100%. So the interference will also not grow with the number of users, and the SINRs will not decrease.

-

(ii)

The (power) dissatisfaction level is larger for higher data rates. This is quite obvious.

-

(iii)

The (power) dissatisfaction level is larger for the larger

. With smaller P0, the users can afford more PRBs, compare (14), whereas the interference level goes down as well (note that the other cells will reduce P0 as well in our model). So the SINRs remain the same as long as we do not enter noise limited regimes.

. With smaller P0, the users can afford more PRBs, compare (14), whereas the interference level goes down as well (note that the other cells will reduce P0 as well in our model). So the SINRs remain the same as long as we do not enter noise limited regimes. -

(iv)

With 512 kbps and

we even have a "dissatisfaction floor," that is, there will be power limited users even in an empty system. That is, high uplink data rates can only be supported with small

we even have a "dissatisfaction floor," that is, there will be power limited users even in an empty system. That is, high uplink data rates can only be supported with small  values (or by relaxing the ATB power constraint (14)).

values (or by relaxing the ATB power constraint (14)).

Note that the previous figure did not take into account users which cannot be served due to the lack of bandwidth. Figure 6 shows the total number of unsatisfied users according to (34), that is, the sum of power- and load-unsatisfied users. Control limitation is not considered, that is,  .

.

Certainly we can recognize the aforementioned dissatisfaction floor for 512 kbps and  in this figure. Otherwise, the impact of the P0 value is almost negligible since adding users beyond 100% virtual load obviously means load-unsatisfied users hiding the aforementioned limit for the dissatisfaction level due to the power constraint. If we target a typical overall dissatisfaction level of 5%, the uplink can satisfy 10, 21, and 56 user with 512 kbps, 256 kbps, and 96 kbps, respectively. The cell throughput with the smaller rates is around 5.4 Mbps whereas the 512 kbps case is slightly worse with 5.4 Mbps due to the more critical power limitation.

in this figure. Otherwise, the impact of the P0 value is almost negligible since adding users beyond 100% virtual load obviously means load-unsatisfied users hiding the aforementioned limit for the dissatisfaction level due to the power constraint. If we target a typical overall dissatisfaction level of 5%, the uplink can satisfy 10, 21, and 56 user with 512 kbps, 256 kbps, and 96 kbps, respectively. The cell throughput with the smaller rates is around 5.4 Mbps whereas the 512 kbps case is slightly worse with 5.4 Mbps due to the more critical power limitation.

As expected the CBR capacity is significantly below the best effort capacity. However, the difference is smaller than in the downlink, since the power control compensates for a part of the SINR loss of cell edge users.

5.4. Heterogeneous Scenario

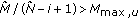

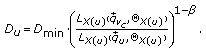

Next we will leave the homogeneous standard scenario and continue with a heterogeneous scenario with different cell sizes and nonuniform user concentrations. Figure 7 illustrated the scenario which has been proposed in [23]. The eNBs are located on an irregular grid, 8 users are dropped into every cell, and additional 42 users (i.e., 50 users in total) are dropped into cell no. 11 simulating a hot spot. All users use a CBR of 64 kbps. For every cell  an individual

an individual  is chosen such that the

is chosen such that the  operator in the power control equation (2) expires in roughly 5% of the cell area.

operator in the power control equation (2) expires in roughly 5% of the cell area.

We will also look at load adaptive power control(LAPC) as proposed in [24] where the  s are reduced in cells which only carry a small load. In the CBR model reducing

s are reduced in cells which only carry a small load. In the CBR model reducing  blows up the resource consumption since the resulting SINR loss has to be compensated by bandwidth. We use a very similar approach to [24] and update the

blows up the resource consumption since the resulting SINR loss has to be compensated by bandwidth. We use a very similar approach to [24] and update the  at time step

at time step  depending on the previous value

depending on the previous value  and the previous virtual load

and the previous virtual load  (note that this equation is in dB scale):

(note that this equation is in dB scale):

where  is the virtual load which we are targeting. In theory we may want to target 100%; however, experience has shown that a margin should be left for handover users so that we will use

is the virtual load which we are targeting. In theory we may want to target 100%; however, experience has shown that a margin should be left for handover users so that we will use  . The rule means that we increase the current

. The rule means that we increase the current  if the load is above target, and we decrease it if the load is below the target; however, we will not increase the initial

if the load is above target, and we decrease it if the load is below the target; however, we will not increase the initial  which has been defined above. Note that this automatic adaptation of a cell parameter can already be considered as a SON mechanism.

which has been defined above. Note that this automatic adaptation of a cell parameter can already be considered as a SON mechanism.

Figure 8 depicts the virtual loads in the overloaded cell no.11 and its neighbors over time where we have switched on the LAPC at  . Before that, the virtual loads are rather small (except the overloaded cell no.11) and different in every cell depending on the exact position of the users and the cell shape/size. After switching on the LAPC the virtual load in all low-loaded cells approaches the target

. Before that, the virtual loads are rather small (except the overloaded cell no.11) and different in every cell depending on the exact position of the users and the cell shape/size. After switching on the LAPC the virtual load in all low-loaded cells approaches the target  .

.

The time characteristics of the corresponding  s are shown in Figure 9. Without LAPC we can observe that the

s are shown in Figure 9. Without LAPC we can observe that the  s depend on the cell size. Large cells have small

s depend on the cell size. Large cells have small  s and vice versa (due to the aforementioned 5% rule). After switching on LAPC, the low-loaded cells reduce their

s and vice versa (due to the aforementioned 5% rule). After switching on LAPC, the low-loaded cells reduce their  s whereas cell no.11 does not change it.

s whereas cell no.11 does not change it.

Now let us look at the impact of the LAPC on the distribution of the interference over thermal(IoT) values. Those are based on the  samples used for the Monte Carlo approach defined in (10); the exact definition of the (instantaneous) IoT is given by

samples used for the Monte Carlo approach defined in (10); the exact definition of the (instantaneous) IoT is given by

leading to  IoT samples per cell. Figure 10 shows the cumulative distribution function of the IoT values (in dB) in cell no.11 before and after switching on LAPC, and it also displays the linear and the harmonic averages of the IoT given by

IoT samples per cell. Figure 10 shows the cumulative distribution function of the IoT values (in dB) in cell no.11 before and after switching on LAPC, and it also displays the linear and the harmonic averages of the IoT given by

With LAPC the CDF is steeper since the users spread their data rate over a larger bandwidth leaving less PRBs unused (without interference) and leading to a smoother interference. The interference of an individual user per PRB certainly goes down significantly (with the  reduction); however, it has to occupy more PRBs to reach its CBR. Still, the linear average of the IoT is smaller with LAPC since the rate function is concave over a wide area meaning that decreasing the power can be compensated by a smaller increase of the bandwidth. However, the harmonic average shows a surprising picture. The harmonic average decreases with LAPC which is a consequence of the larger variance of the IoT. Note that we have clearly shown in Section 2.3 that the harmonic average is actually the relevant measure. This also manifests in the distribution of the average user SINRs defined in (7) which are shown in Figure 11 for the overloaded cells.

reduction); however, it has to occupy more PRBs to reach its CBR. Still, the linear average of the IoT is smaller with LAPC since the rate function is concave over a wide area meaning that decreasing the power can be compensated by a smaller increase of the bandwidth. However, the harmonic average shows a surprising picture. The harmonic average decreases with LAPC which is a consequence of the larger variance of the IoT. Note that we have clearly shown in Section 2.3 that the harmonic average is actually the relevant measure. This also manifests in the distribution of the average user SINRs defined in (7) which are shown in Figure 11 for the overloaded cells.

The LAPC has degraded the SINR in the overloaded cell even though the  has not been reduced there since the more fluctuating interference obviously offers more potential for the link adaptation (which is assumed to be ideal in our model). This is also visible in the virtual load of the overloaded cell no.11 in Figure 8 which has slightly been increased by LAPC (as a result of the decreased SINRs). This is a contrast to the results in [24] where LAPC helps to improve the system. Fluctuating interference has a negative impact on link adaptation (i.e., selection of modulation and coding schemes, scheduling, etc.). In other words, smoothening the interference through LAPC will improve link adaptation. Unfortunately this effect is not covered in our simplified model, where link adaptation is always assumed to be ideal. Hence, our model can exploit the aforementioned potential offered by fluctuating interference, which is not the case in reality.

has not been reduced there since the more fluctuating interference obviously offers more potential for the link adaptation (which is assumed to be ideal in our model). This is also visible in the virtual load of the overloaded cell no.11 in Figure 8 which has slightly been increased by LAPC (as a result of the decreased SINRs). This is a contrast to the results in [24] where LAPC helps to improve the system. Fluctuating interference has a negative impact on link adaptation (i.e., selection of modulation and coding schemes, scheduling, etc.). In other words, smoothening the interference through LAPC will improve link adaptation. Unfortunately this effect is not covered in our simplified model, where link adaptation is always assumed to be ideal. Hence, our model can exploit the aforementioned potential offered by fluctuating interference, which is not the case in reality.

Although we have gained important insights by this analysis, it also reveals a current limitation of the model. A remedy could be based on the principles of [25], where the rate function is elaborated by the introduction of a correlation between the SINR at the moment of choosing the modulation and coding scheme and the moment of applying it (where the interference might have changed). This correlation would increase through LAPC.

5.5. Simulation Runtime

Finally we will look at the runtime performance of the simulation. Figure 12 shows the simulation time for one simulation step versus the average number of users per cell. It turned out that the number of samples used for the Monte Carlo integration in (10) has significant impact. As already mentioned, convergence is achieved for  . Fortunately we observe that further reduction of this number does not bring additional runtime benefit. The increase is linear with respect to the number of users, which is not surprising. With 50 users per cell and a simulation step of 1 sec, which is sufficient for many applications, we are a factor 2 above real-time. Recall that we have a fully heterogeneous 57-cell network, and no homogeneous properties are exploited.

. Fortunately we observe that further reduction of this number does not bring additional runtime benefit. The increase is linear with respect to the number of users, which is not surprising. With 50 users per cell and a simulation step of 1 sec, which is sufficient for many applications, we are a factor 2 above real-time. Recall that we have a fully heterogeneous 57-cell network, and no homogeneous properties are exploited.

6. Conclusions

We have presented a very efficient modeling approach for uplink investigations focussing on the LTE standard. QoS and radio resource management (which typically work on a millisecond time scale) are modeled in a very abstract but still accurate way such that the essential behavior is still included. By those means we can decrease simulation runtime far below real-time.

This is in particular helpful, even necessary, for simulations covering long time intervals. The most important applications are investigations on self-optimizing networks since SON mechanisms are typically very slow control loops and converge over hours or even days. Conventional system level simulators cannot serve this purpose. On the other hand, QoS and mobility issues are of utmost importance and can not be neglected when studying SON which makes static tools inappropriate as well. We are closing the gap between too slow but elaborate system level simulators with full mobility and QoS support on one side and rough static simulators which can lead to very fast results.

We have seen that uplink modeling is much more complicated than downlink modeling. The key differences are the uplink power control (including the associated individual UE power budgets) and the multiple-access structure of the uplink (leading to extremely fluctuating interference). We have derived an average uplink SINR which is equivalent to the downlink SINR which is typically intuitively used. We have observed that the uplink interference has to be averaged in a harmonic way.

Different traffic/scheduler assumptions have been discussed. Again in contrast to downlink, there is no unique definition of a resource fair scheduler in the full buffer case. We have given two solutions called strict and modified resource fair. Furthermore, throughput fair solutions as well as CBR solutions targeting a given bit rate have been defined. In order to evaluate the system performance we have discussed uplink satisfaction in the CBR case. In addition to load limitation, we have observed that satisfaction due to power limitation and due to control channel limitation is highly relevant in uplink, too.

Limitations of the abstract models have been addressed as well. In particular, RRM details such as the exact algorithms for MCS selection, multi-user diversity gains, and imperfect channel estimation are hidden behind the abstract models (although the essence of fairness issues is considered). Furthermore, the capability to consider more elaborate traffic models (different from pure CBR and pure best effort) is limited. We are giving an outlook on possible extensions in Appendix B.

We have given simulation results using the derived modeling approach. In the specified LTE test cases our results match very well the typical performance assumptions. We have also given results for the CBR case using different target bit rates and analyzed the impact of power limitation. Finally we were looking at a heterogeneous scenario with different cell sizes and non-uniform user placement. We have considered load-adaptive power control as an example for a SON mechanism. This scenario has revealed some limitations of our modeling approach which have to be improved in the future.

In this paper we have only looked at a small subset of the proposed SON use cases since the focus was on the introduction of the framework. Certainly the model can be used for all other SON use cases as well, such as load balancing, coverage and capacity optimization, or mobility robustness optimization.

Appendices

A. Discussion of Uplink Fairness

In this section we will compare the uplink fairness with the downlink fairness. We will show that themodified resource fair scheduler in the uplink achieves a comparable fairness as a typical resource fair scheduler in downlink.

In downlink, the SINRs on a PRB degrade towards the cell edge more severe than the pathloss law, since the interference grows in addition. With a resource fair scheduler, the throughputs behave accordingly. However, we can improve cell edge users arbitrarily by assigning them more PRBs (nonresource fair scheduling).

In the uplink, the degradation towards the cell edge is different. By purely looking at the power control equation (2), bandwidth limitation (13), and SINR definition (7), we make the following observations.

-

(1)

The uplink interference is induced at the eNB antennas and therefore is the same for all users (as long as we do not assume intercell interference coordination).

-

(2)

Assuming no power control

(resulting in strict resource fairness, that is, one PRB per user), that is, each UE transmits with maximum power, the SINRs per PRB would degrade with the pathloss. Note that this is still "fairer" as in the downlink (where interference increases in addition).

(resulting in strict resource fairness, that is, one PRB per user), that is, each UE transmits with maximum power, the SINRs per PRB would degrade with the pathloss. Note that this is still "fairer" as in the downlink (where interference increases in addition). -

(3)

Assuming power control with full pathloss compensation

(and adaptive transmission bandwidth), that is, all UEs are received with the same power per PRB, the SINRs per PRB would be the same for all UEs, but the assigned bandwidth degrades with the pathloss, copmared with (14) unless the

(and adaptive transmission bandwidth), that is, all UEs are received with the same power per PRB, the SINRs per PRB would be the same for all UEs, but the assigned bandwidth degrades with the pathloss, copmared with (14) unless the  s are rather small. So the throughputs degrade with the pathloss (which is a little steeper than the upper case due to concavity of the rate function).

s are rather small. So the throughputs degrade with the pathloss (which is a little steeper than the upper case due to concavity of the rate function). -

(4)

Assuming power control with fractional pathloss compensation

(and adaptive transmission bandwidth), the SINRs per PRB would degrade less severely than the pathloss; however, the assigned bandwidth degrades with the "rest" of the pathloss law. So in total the throughputs again will degrade with pathloss, with the slope being in between the upper two cases.

(and adaptive transmission bandwidth), the SINRs per PRB would degrade less severely than the pathloss; however, the assigned bandwidth degrades with the "rest" of the pathloss law. So in total the throughputs again will degrade with pathloss, with the slope being in between the upper two cases.

So in either case the throughputs will degrade with the pathloss, either via SINR degradation (for  ) and / or via the ATB scheduler. The degradation will be similar to the downlink. All cases refer to the definition of the modified resource fair scheduler.The strict resource fair solution will lead to more fairness, that is, less throughput degradation for

) and / or via the ATB scheduler. The degradation will be similar to the downlink. All cases refer to the definition of the modified resource fair scheduler.The strict resource fair solution will lead to more fairness, that is, less throughput degradation for  . For the special case of

. For the special case of  strict resource fairness even leads to throughput fairness.

strict resource fairness even leads to throughput fairness.

Despite similar fairness behavior, the uplink scheduler has much less degrees of freedom to trade throughput among the users (due to individual power budgets). The only way to extend the strict throughput limit of cell edge users is to reduce the intercell interference which unfortunately lies outside the responsibility of the serving cell. Even more severe, the neighbors can only decrease interference by degrading their own users. Hence, whereas in downlink we can trade throughputs between users, in uplink we need to trade throughputs between cells.

B. Traffic Assumptions

We have already observed that the individual power limitation in the uplink results in a bandwidth limitation  (the number of PRBs for edge users is limited) and thereby in a tight data rate limit. This is different from the downlink, where basically each PRB comes along with its own power budget, so that assigning more PRBs automatically means assigning more power.

(the number of PRBs for edge users is limited) and thereby in a tight data rate limit. This is different from the downlink, where basically each PRB comes along with its own power budget, so that assigning more PRBs automatically means assigning more power.

As a consequence, in the uplink we can only guarantee small data rates to cell edge users. So if we want to assume a common CBR model for all users, it has to be very small such that the edge users have a fair chance to achieve it. With such a setting there are basically 3 different methods how capacity limit could be achieved.

( ) Common CBR

) Common CBR

The straightforward solution is to consider a large number of users. This would increase simulation runtime, and large data rates would not occur at all.

( ) Common CBR Extended with Full Buffer

) Common CBR Extended with Full Buffer

With a smaller number of users we could think about distributing the excess capacity (i.e., PRBs) among those users who still can afford more PRBs. Basically this would be a mixture of CBR and full buffer model, which can be referred to as guaranteed bit rate(GBR) model. The drawback is that we would need another metric (in addition to the satisfied users due to load and power) accounting for users with higher throughput (i.e., 95% percentile). Furthermore we have to set a rule how the excess capacity is distributed among the users.

( ) User-Specific CBR

) User-Specific CBR

Finally, we could set different bit rate requirements  for the users, for example, depending on the pathloss. Edge users would get small

for the users, for example, depending on the pathloss. Edge users would get small  's, and close users would get higher

's, and close users would get higher  's. This might be the most convenient solution and probably the most realistic one as well. However, we need to find an appropriate rule to set the individual rate requirements

's. This might be the most convenient solution and probably the most realistic one as well. However, we need to find an appropriate rule to set the individual rate requirements  's, which is absolutely not straightforward. We will propose a simple mechanism with the following characteristics.

's, which is absolutely not straightforward. We will propose a simple mechanism with the following characteristics.

-

(a)

We define a minimum data rate

which lower-bounds all rate requirements, that is,

which lower-bounds all rate requirements, that is,  .

. -

(b)

The rate requirement for the worst user

(i.e., with largest pathloss) in every cell

(i.e., with largest pathloss) in every cell  is set to the minimum rate, that is,

is set to the minimum rate, that is, (B1)

(B1) -

(c)