Abstract

Recent work based on an approximation method suggested some odd behaviors may be possible in solutions to a generalized model for compact stars. We show that it was the error in these approximations and error coming from non-physical boundary conditions which lead to the odd behavior. As it turns out, the generalized model for compact stars actually admits an exact solution, and we obtain this exact solution in closed form. The exact solution agrees with what one would physically expect from a compact star, and hence we use this solutions to calculate various quantities of physical interest in closed form, without having to resort to approximations.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In the brief paper, we shall be concerned with obtaining an exact solution to a generalized model for compact stars. Such a model was discussed in Aziz et al. [1], and follows from earlier work of Sorkin et al. [2] on the entropy of self-gravitating radiation in a spherical body. Before obtaining the exact solution in Sect. 2, and discussing relevant physical quantities of interest which may be derived from this solution in Sect. 3, we summarize the derivation of the model below. In Sect. 4, we compare the exact solution with the approximations obtained in Aziz et al. [1]. We then offer concluding remarks in Sect. 5.

Consider the metric

for a system with spherical symmetry. Here, m(r) is the mass distribution within a radius r of the spherically symmetric body, while \(g_{tt}(r)\) is the time-time component of the metric.

Aziz et al. [1] consider a linear equation of state given by

where \(p_\mathrm{r}\) is the radial pressure and \(\rho \) is the density corresponding to the mass distribution. As in [2], the energy density and entropy density depend on the locally measured temperature (T) like

where b is a constant of order unity (in Planck units), on the assumption that the number of species of radiation is of order unity (see [3]).

For the matter distribution up to a radius \(r=R\), the total entropy is given by

Upon defining the Lagrangian

we may write

where \(\alpha = \frac{4}{3}b^{1/4}\) and hence we have \(s = \alpha (\rho )^{3/4}\). The Euler–Lagrange equation for (6) is

and from this we obtain the equation of interest,

This is the equation derived in Aziz et al. [1] for a generalized model for compact stars, and is also equivalent to earlier work of Sorkin et al. [2].

The point of this paper is to give the exact solution to (8) for appropriate boundary conditions. As we shall show, the exact solution can actually be given in closed form. This solution differs from the solution given in Aziz et al. [1], since in that paper the solution was only an approximation, and the condition at one boundary was non-physical, resulting on non-physical results over part of the spatial region close to the exterior of the star. Using the exact solution, we obtain more physically relevant values of quantities such as density, anisotrophy, redshift, and can show that the exact solution always satisfies Buchdahl’s condition. Furthermore, the exact solution always satisfies the NEC, WEC, SEC energy conditions.

2 Exact solution to a generalized model for compact stars

Aziz et al. [1] apply the homotopy perturbation method in order to approximate the solution to (8). In order to obtain a solution, the invoke the boundary conditions

although the physical meaning of these conditions is never stated. It appears that these conditions were simply selected arbitrarily, to make the solution procedure work. They then obtain their approximate solution, although curiously they did not think to study the error of their approximation.

In order to derive the correct conditions, let us recall that (8) was cast as the system

in the original work on this model given in Sorkin et al. [2]. Here we have \(\mu = \frac{m}{r}\), \(q = \frac{\mathrm{d}m}{\mathrm{d}r}\), and \(z=\ln (r)\). Recall that Sorkin et al. [2] require \(\mu \rightarrow \frac{3}{14}\), \(q\rightarrow \frac{3}{14}\) as \(r\rightarrow \infty \), as this is just the steady state of the system (10), (11).

From this, it is clear that the needed boundary conditions are

Using the boundary conditions (12) with the differential equation (8), we find that there exists the exact, closed form solution

3 Physical quantities of interest

With the proper form of m(r) as given in (13), we can now obtain certain physical quantities of interest in closed form. We list these quantities here.

Density:

\(g_{tt}\):

total mass:

radial pressure:

tangential pressure:

anisotropy:

We have the compactness

and the redshift

At \(r=R\), Buchdahl’s condition is

For our solution (13), Buchdahl’s condition always holds:

There are a few energy conditions one often checks solutions against, and these can include the null energy condition (NEC), the weak energy condition (WEC), and the strong energy condition (SEC). For the solution (13), note that the energy conditions

as mentioned in [1], are always satisfied, since \(\rho >0\), \(p_r >0\), and \(p_t >0\) for all \(r>0\). In contrast, the approximations of [1] satisfied these conditions only up to a fixed radius, beyond which some of the conditions fail. Hence, we can be comfortable that the true compact star solutions will obey these needed physical energy conditions.

4 Comparison with the solution of Aziz et al. [1]

In contrast to the exact solution we give, Aziz et al. [1] reported an approximate solution of the form

where a is an arbitrary parameter introduced through an application of the homotopy analysis method. Note that this solution satisfies the boundary conditions (9) rather than the boundary conditions (12) compatible with Sorkin et al. [2]. While Aziz et al. [1] choose the parameter a as they like (in order to perform data fitting), we note that if this parameter were arbitrary, this would mean that there are infinitely many solutions to the problem (8), and hence that problem would be ill-posed. However, this is not likely the case. Instead, note that (27) was obtained through an iterative approach, but was never actually placed back into Eq. (8). Further, there was never any error analysis for this solution (which would be useful, due to the approximate nature of the solution). Let us go ahead and plug the solution (27) into Eq. (8). To this end, define the residual operator \(\text {Res}\,[m]\) by

Therefore, an exact solution to (8) will have \(\text {Res}\,[m]=0\) for all r. We find that for the approximate solution (27)

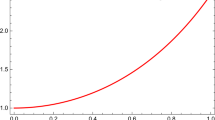

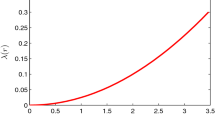

where the coefficients are functions of a and R. For the parameter values \(a=-0.01860326472\,\text {km}^{-1}\) and \(R=10\,\text {km}\) used in [1], we can plot the residual over r, finding actually that the residual is monotone increasing over space. This makes sense, as errors in the iterative approach compound as the spatial interval is increased. The maximal residual is at \(r=10\), and take the value \(\text {Res}\,[m]_{r=10} = 0.2280848142\). For comparison, \(m(10)=1.255406018\) for the approximate solution (27). Therefore, the residual error is about one-sixth the value of the function itself, and hence it is rather large. If the approximation was accurate, we would expect the residual error to be orders of magnitude smaller than the function value. Further, if we compare the approximation to the true solution (13) (which takes the value \(m(10)=15/7 = 2.1429\)), we find that the relative error is \(41\%\). While it may be tempting to try to select a different value of a in order to obtain a better fit, we note that the residual operator tends to zero only as a tends to zero. Had the authors attempted to improve their approximation, they would have seen that \(m(r)=0\) is the most optimal approximation under their scheme. Actually, the zero solution makes sense given their boundary conditions. Instead, they choose a in order to match their approximation to data, and thus did not notice this shortcoming as they did not check to see that their solution was actually a reasonable solution to the model.

5 Conclusions

We have given the exact solution, in closed form, to a generalized model of compact stars originating in the model put forth by Sorkin et al. [2]. In doing so, we have pointed out some mathematical and physical inaccuracies with the approximations given in Aziz et al. [1]. We conclude that the tables of Aziz et al. [1] appear somewhat accurate more due to data fitting than to the solution of the model (8) (in particular, the model parameters are selected to fit the data, but they do not give a solution to the underlying differential equation). With the exact solution we have obtained, we are able to calculate various physical quantities of relevance, without having to resort to approximation. For instance, the exact solution given here will always obey the needed energy conditions, in contrast to the solutions of Aziz et al. [1] which are non-physical in that they fail to satisfy the same energy conditions over parts of the spatial domain. The exact solution should, furthermore, be of interest to researchers interested in compact stars, as the exact solution may be used very easily to obtain physical quantities of interest.

References

A. Aziz, S. Ray, F. Rahaman, Eur. Phys. J. C 76, 248 (2016)

R.D. Sorkin, R.M. Wald, Z.J. Zhang, Gen. Relativ. Gravit. 13, 1127 (1981)

G.W. Gibbons, M.J. Perry, Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 358, 467 (1978)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Funded by SCOAP3

About this article

Cite this article

Van Gorder, R.A. Exact solution to a generalized model for compact stars. Eur. Phys. J. C 77, 74 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-017-4632-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1140/epjc/s10052-017-4632-0