Abstract

The global community can address the collapse of investment following COVID-19, drive digital transformation, and help achieve the SDGs through five actions: (1) establish a Facility and Fund to provide resources for technical assistance and facilitate private–public collaboration, including through a new EASI Alliance, (2) endorse a Sustainable Investment Framework to advance such collaboration, through aligning and coordinating efforts, (3) adopt specific investment policies and measures to support sustainable FDI for sustainable development, prioritizing linkages, (4) adopt specific policies and measures to facilitate investment in the digital economy, accelerating productive transformation while building resilience, and (5) develop partnerships and industry-based coalitions to operationalize these efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

In this ‘Decade of Action’, a dash to reach the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) before the 2030 deadline, the world is facing a double challenge. First, the financing gap to achieve the SDGs may be growing, not shrinking. Recent IMF estimates have placed the financing gap to the SDGs across 121 emerging and low-income developing countries at $2.6 trillion (Gaspar, Amaglobeli, Garcia-Escribano, Prady, & Soto, 2019); this is $100 billion more than the landmark estimate five years prior, which suggested the financing gap to be an annual $2.5 trillion (UNCTAD, 2014). The Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development has stated with alarm that “the international economic and financial systems are not only failing to deliver on the SDGs, but … there has been substantial backsliding in key action areas,” saying that “Governments, businesses and individuals must take action now to arrest these trends and change the trajectory.” (UN, 2020a).

Second, global FDI has fallen by a staggering 49% in the first half of 2020 following the COVID-19 pandemic (UNCTAD, 2020). Yet, developing economies (and especially the least developed among them) often rely on FDI as their largest source of external finance, and FDI brings not only capital but also embedded attributes that can lead, inter alia, to positive effects on gender inclusion, employment (job creation, training, higher wages), productivity growth, innovation, exports, as well as knowledge and technology transfer, both directly and through spillovers (OECD, 2019; Perea & Stephenson, 2018; Stephenson, 2018; WBG, 2020). FDI is thus an essential ingredient to help achieve SDGs 1 through 15.

At the same time, there are mechanisms that can help address these challenges and help get the global goals back on track. On the one hand, both policymakers and firms increasingly embrace the five Ps in their approach to investment, whereby profits are generated responsibly and sustainably and contribute to People, Planet, Prosperity, and Peace through Partnerships. On the other hand, digitization is offering channels of adaptation and new modalities of delivering goods and services, as well as potentially an additional vector for sustainable development.

The question, then, is how to restart investment flows in a way that helps firms and societies adapt to the downturn, seizing opportunities of digitization to transform ways of doing business, while establishing frameworks to ensure that investment flows make the maximum contribution to sustainable development.

This is no easy task for a number of reasons.

On the one hand, achieving the SDGs requires a systems approach, understanding how different reforms can impact each other and how the actions of myriad actors can be aligned and coordinated. This requires “the involvement of the whole society (state, market, civil society, knowledge institutes)” (van Zanten & van Tulder, 2020: 2). Yet, there is confusion over what constitutes sustainable investment and, more importantly, over the policies and measures available for governments to attract, encourage, and stimulate such investment. This is because, given the importance of leveraging investment for development, there has been a proliferation of recent independent initiatives: an action plan to invest in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (UNCTAD, 2014), identification of the main characteristics of sustainable FDI to permit better targeting (Sauvant & Mann 2017), development of new funding mechanisms (WBG, 2018), and new FDI quality indicators (OECD, 2019). This is a challenge to aligning efforts and optimizing resources.

On the other hand, attracting and facilitating investment in the digital economy may require specific policies and measures to create an enabling environment – what can be called a “digital friendly” investment climate. This is because there are important differences between firms in traditional industries and firms in highly digitalized industries in terms of their investment decision-making and footprint (Casella & Formenti, 2019). In addition, investment in the digital economy is one of the areas of geo-economic tension, as economies increasingly use industrial policy and strategic investment to contest the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Chen et al., 2019; Ciuriak, 2019).

This article proposes five solutions to address these challenges, reflected in the article’s structure: (1) A Facility and Fund to provide technical assistance to developing economies (and especially the least developed among them) to help overcome capacity constraints, while facilitating public–private collaboration on investment reforms that increase both the quantity and quality of investment flows, including through a new EASI (Enabling Action on Sustainable Investment) Alliance. (2) A Sustainable Investment Framework to advance such collaboration through a common language and understanding of the different levers available to advance sustainable investment reforms. This is important to help align and coordinate public and private initiatives. (3) Concrete, actionable investment policies and measures to facilitate sustainable FDI flows and advance sustainable development (foremost of which are measures to support linkages between foreign affiliates and domestic firms), and the importance of including such measures in, and then finalizing, a framework on investment facilitation for development being negotiated at the World Trade Organization (WTO). (4) Concrete, actionable investment policies and measures to advance digital development, including through supporting investment in digital infrastructure, in digital firms, and in digital adoption by traditionally non-digital sectors. (5) Creating partnerships and industry-based coalitions as a mechanism to operationalize the above, sharing their insights with public and private actors to accelerate recovery following the COVID-19 crisis, while driving and deepening the effect of investment on development and digitization.

INVESTMENT FACILITY AND FUND

Countries should create an International Investment Support Program, consisting of an Investment Facility and Fund, to boost both the quantity and quality of investment flows (Sauvant, 2020). Recovery from the global downturn, especially in the case of developing countries, will be accelerated if international investment flows are ramped up as soon as possible.

The Facility would develop an overall strategic approach and provide coordination in the currently fragmented and under-resourced investment-support landscape. The Fund would provide resources for targeted technical assistance to governments to tackle specific bottlenecks identified by governments and firms.

The Program should support the entire range of activities geared toward substantially increasing the quantity and quality of investment flows to beneficiaries. The beneficiaries should be developing countries (including economies in transition), especially the least developed among them. It should focus on the comparative advantage of each intergovernmental institution providing technical assistance in the investment space, especially the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), the World Bank Group (WBG), the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO), and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Moreover, this Program should encourage these institutions to team up with non-governmental organizations undertaking practical work in the investment area, such as the World Economic Forum (WEF). Thus, it could help facilitate public–private collaboration to identify specific investment bottlenecks and blockages, as well as potential solutions, including through establishing an EASI Alliance modelled on the Global Alliance for Trade Facilitation (GATF). The Program – to be located in an appropriate organization – could be implemented by a small secretariat and financed by governments interested in improving the ecosystem for investment flows.

SUSTAINABLE INVESTMENT FRAMEWORK

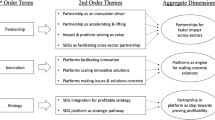

The work of the International Investment Support Program can be implemented within a framework that can help align efforts among different actors. In other words, policymakers and firms need a clear picture of the different channels to pursue sustainable investment and the different tools at their disposal before those channels and tools can be coordinated through the Facility and Fund. To this end, the Facility can endorse a framework wherein sustainable investment comprises five complementary and mutually reinforcing dimensions (see Figure 1).

Sustainable investment framework (WEF, 2019a) Note: It is difficult to distinguish between investment promotion and investment facilitation, which is why in the figure they are presented as a continuum with the same color-scheme; nevertheless, they are kept as two dimensions in the framework to make it clearer and more easily actionable.

Sustainable Investment Policies

These are key to creating the underlying framework for investment to take place in alignment with environmental, social, economic, and governance principles. Concretely, these can include human and labor rights, health and safety standards, and social and environmental protection. An example of a tool is the use of environmental and social impact assessments. According to a 2019 World Bank-World Association of Investment Promotion Agencies survey, 54% of Investment Promotion Agencies surveyed evaluated investors for environmental and/or social impact before providing support – whether services or approval of grants (Omic & Stephenson, 2019). Policies are also important to keep economies open to investment flows, resisting protectionist developments regarding investment such as those taking place in trade as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. These include notably export controls, especially of medical supplies, but they were also being considered for food (Evenett, 2020; Glauber, Laborde, Martin, & Vos, 2020).

Sustainable Finance Mobilization

This entails a framework for increasing the flow of capital and, especially, the flow of capital to sustainable activities (for a discussion of the challenges to mobilizing private finance to achieve the SDGs, see OECD, 2016a). This requires stakeholders to have information regarding the sustainability behavior of different firms. Thus, policymakers, regulators, investors, media, and civil society can reward sustainable behavior and condemn unsustainable behavior, which aligns market mechanisms with development goals. An example of a tool is environmental and social reporting by firms or reporting requirements to be listed on stock exchanges through the Sustainable Stock Exchanges initiative (see Section on Sustainable Investment Policies and Measures).

Sustainable Investment Promotion

Such efforts can drive sustainable investment through (a) targeting investors in sectors that are particularly conducive to the SDGs, (b) targeting investors with a sustainability mission, and (c) creating a pipeline of sustainable bankable projects. An example of a tool is investment incentives made conditional on the sustainability behavior of firms (see Section on Sustainable Investment Policies and Measures) (Sauvant & Gabor, 2019). Another tool to help guide promotion to SDG needs is the SDG Index (Sachs, Schmidt-Traub, Kroll, Lafortune, Fuller & Woelm, 2020).

Sustainable Investment Facilitation

Such efforts can drive sustainable investment by providing greater facilitation services and support to investment that is aligned with the development goals of the economy. An example of a tool is providing greater support to investors that make a commitment to operate sustainably, such as through creating a category of Recognized Sustainable Investor (RSI) (Sauvant & Gabor, 2019). Another example is the use of guarantees or insurance to support and protect sustainable investment (MIGA, 2013). (For a discussion of guiding principles for sustainable investment facilitation, see Berger, Ghouri, Ishikawa, Sauvant, and Stephenson (2019)).

Sustainable Development Impact

This involves measures to maximize the positive development impact – and minimize any potential negative impacts – from investment. This can take place through increasing absorptive capacity, indicators to monitor and measure impact, and stakeholder engagement. An example of a tool is supplier development programs to create linkages between foreign and domestic firms (see Section on Sustainable Investment Policies and Measures) (WBG, n.a.).

Through a clear understanding of these different dimensions, cooperation both among and within economies on sustainable investment can be furthered. More details on the five dimensions – including elements, tools, and actors across each – is laid out in Appendix 1 (for an earlier overview, see UNESCAP, 2017).

SUSTAINABLE INVESTMENT POLICIES AND MEASURES

Within the framework, there are a number of investment policies and measures that can advance the SDGs. Investment is a necessary input to help achieve SDGs 1 to 15. Moreover, there is very strong evidence that FDI often brings additional benefits to host and home economies, including to tackle poverty (SDG 1), increase gender equality (SDG 5), provide decent work and economic growth (SDG 8), and increase both innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9) (OECD, 2019; Perea & Stephenson, 2018; Stephenson, 2018; WBG, 2020). In addition, investment explicitly appears as a target in SDGs 1, 2, 7, and 17, as well as FDI in SDG 10, variously calling to ‘accelerate’, ‘increase’, ‘promote’ or ‘encourage’ investment and FDI in support of these Goals (UN, 2020b). FDI also appears as an indicator in SDGs 10 and 17 (see Appendix 2 for the full text of these targets and indicators). Actions taken to drive more and better investment are therefore directly supportive of the SDGs, their targets, and their indicators.

This section will present six specific measures that could be prioritized by policymakers, as the evidence indicates that these measures may be amongst the most impactful regarding leveraging investment for the SDGs. Five measures will be briefly outlined in next subsection on measures, and then a sixth, support for linkages, described in more detail in the subsequent subsection, given its critical importance. Firms have responded supportively to the global adoption of the SDGs (van Zanten & van Tulder, 2018), but there is an ‘intention-realization gap’ (van Tulder, 2018). These policies and measures are intended to help provide tools for the two-way institutional dynamics between policymakers and firms as “MNEs help form institutions that can not only govern, but also guide, their sustainable development activities” (van Zanten & van Tulder, 2020: 4–5).

One way to advance such measures is to include them in framework currently being negotiated at the WTO on investment facilitation for development. Modelling of different scenarios of an eventual agreement based on level of ambition suggests that global welfare can increase by between $230 billion (low-ambition scenario) and $850 billion (high-ambition scenario) (Balistreri, Berger & Olekseyuk, 2020). The WTO framework therefore has the potential to increase not only investment flows but their sustainable development impact if sustainable investment measures are included, and should be finalized expeditiously to support achievement of the SDGs. The WTO framework can also then help inform regional and bilateral frameworks (e.g., the planned Investment Protocol under the African Continental Free Trade Agreement) in a rationalized and mutually supportive way.

Measures to Advance Sustainable Development Goals for Investment

Include internationally accepted standards and guidelines in domestic frameworks and international investment agreements (IIAs) (for an elaboration, see Sauvant & Gabor, 2019)

The best known and most important among these standards are the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UN, 2011), the International Labour Organization Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy (ILO, 2017), and the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (OECD, 2011). In addition, there are sector-specific supply-chain standards that have also been developed, such as for mining (OECD, 2016b) or agriculture (OECD-FAO, 2016). Leading economies have already started to integrate these into domestic frameworks (China in 2015, EU in 2018, U.S. in 2012). What is new is that IIAs are starting to include these standards and guidelines as well, with application to firms in both the host and home economies. In 2018, four IIAs included such a reference (UNCTAD, 2019).

Make corporate social responsibility (CSR) programs a requirement for firms above a certain size (for an elaboration, see Sauvant & Gabor, 2019)

One way to quickly operationalize international standards at a microeconomic level is for policymakers to require firms operating in or from their jurisdiction to adopt CSR programs, including a requirement to publicize if these programs include international standards. India has made CSR programs a requirement for firms investing in its economy, although it has stopped short of requiring such programs for foreign affiliates of Indian firms invested abroad (Government of India, n.a.). South Africa has included CSR programs as one of 12 principles in the voluntary guidelines for its firms investing in other African economies, but has stopped short of making this a requirement (Government of South Africa Department of Trade and Industry, 2016).

Adopt sustainability reporting requirements for firms

Reporting is essential for stakeholders to allocate capital according to societal values, with firms that score well being rewarded with greater investment and tax breaks, for example. The Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards are the oldest and most widely adopted in this space. The challenge is the proliferation of metrics in recent years, which has created fragmentation and confusion. An effort at integrating different frameworks into one common set of metrics could help accelerate uptake and increase impact (WEF, 2020). These metrics can be designed to track the contribution to SDG targets and indicators.

Align incentives with sustainability behavior of firms

There is growing consensus on the need for incentives (financial and non-financial) to become “smarter.” In practice, this can mean two complementary shifts: first, targeting incentives toward sustainability sectors and investors; second, making incentives conditional on investor behavior, known as “behavioral incentives.” This can be implemented by both home and host governments. Governments can either make incentives conditional on sustainability behavior (a form of “stick”) or provide additional incentives to firms that make more of a contribution to sustainable development (a form of “carrot”). As previewed in the previous section, one way to implement this in practice is by creating a special category of Recognized Sustainable Investor or RSI (Sauvant & Gabor, 2019).

Ensure special attention to the sustainability of infrastructure investments

While all investment can be encouraged to be sustainable through the aforementioned measures, infrastructure investment is particularly important, as the decisions today have repercussions for the duration of the infrastructure’s lifespan and have an especially large effect on climate change. It therefore impacts not only SDG 9 on infrastructure, but also SDGs 7, 11, and 13, respectively on energy, cities, and climate. Current energy, transport, building, and water infrastructure make up more than 70% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Therefore, as new investment replaces existing infrastructure, there is an opportunity for such investment to contribute to climate change solutions (Bhattacharya, Gallagher, Cabré, Jeong, & Ma, 2019; Bhattacharya & Jeong, 2018; Bhattacharya, Oppenheim & Stern, 2015; New Climate Economy, 2016; OECD-WBG-UN Environment, 2018; UNEP, 2016).

Efforts to Create Linkages Between Foreign Investors and Local Firms

One of the key measures to both increase investment flows and their development effects are efforts to create linkages between foreign investors and local firms, and so requires special attention. Having reliable domestic firms that can provide inputs at quality, cost, and volume can be an important determinant for foreign investors to enter a market. At the same time, contracting with domestic suppliers can lead to employment, revenue, and productivity-enhancing knowledge spillovers (Alfaro, Görg & Seric, 2017).

The development of such linkages is affected by a variety of policy and non-policy factors. On the non-policy side, the global context – including macroeconomic factors related to the business cycle and long-term growth as well as geographic and cultural factors – affects FDI trends and sourcing decisions of multinational enterprises (MNEs) (OECD-UNIDO, 2019). Additionally, business models of MNEs and capacities of local firms determine the extent to which MNEs are likely to forge linkages with domestic firms. Policy can play a pivotal role in attracting and anchoring investors through deep linkages with the local economy (UNIDO, 2018; Amendolagine, Presbitero, Rabellotti, Sanfilippo, & Seric, 2017; Amendolagine, Boly, Coniglio, Prota, & Seric, 2013).

The first step to supporting the creation of linkages are measures to improve the overall investment climate, complemented by “light-form” industrial policies. A healthy investment climate can by itself help to create an environment that is propitious for foreign firms to invest and link with local firms. Governments may also decide to implement additional targeted measures to enhance linkages. Effective policies to support creation of inter-firm linkages integrate complementary elements directed to foreign investors and domestic firms. Thus, host country governments may deploy some of the following light-form industrial policy options to hitch FDI to development goals and generate backward linkages as deep as possible into the host economy (Moran, Görg & Seric, 2016; Buzdugan & Tuselmann, 2018). Light-form should be distinguished from “heavy-form”, in that it does not focus vertically on a specific domestic industry. Rather, it seeks to increase the competitiveness of multiple industries at once through modest intervention and support.

Establish hard and soft infrastructure required by investors

This includes transport facilities (roads, airport, ports), adequate and reliable supply of energy, provision of an adequately skilled workforce (including vocational training of specialized workers, ideally designed in cooperation with the investors). Providing such infrastructure is a challenge and may be beyond the reach of developing and least-developed economies by themselves; this argues for the need of development finance and development partners to help provide the building blocks of such infrastructure. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank is a good example of such targeted intervention.

Establish a supportive mechanism to help local firms overcome supply-side constraints

In particular, two types of measures can be fruitful in the long term in this respect – both to develop linkages between local and foreign firms, as well as to strengthen the local industrial structure: the development of a system of quality certification (both at the product and process level) that is often required to operate with foreign firms, and the improvement of the digital infrastructure that allows firms to operate remotely along global production chains and in reaching out to foreign markets (see next section).

Set up a supplier development program to support the match-making process between foreign affiliates and local suppliers

To strengthen the capacity of the domestic economy, the program may offer financing to indigenous suppliers for required investment based on purchase contracts from foreign affiliates (a good example is provided by the Local Industry Upgrading Program of Singapore), or reimburse the salary of a manager in a foreign plant acting as a talent scout among domestic suppliers (as practiced by Singapore’s Economic Development Board) (APEC-UN 2010).

Shape special economic zones (SEZs) in a way that they spearhead into the domestic economy

Avoid SEZ regulations discriminating against the creation of local supplier relationships. Establish a second industrial zone for local suppliers, for instance, through a site geographically adjacent to the official SEZ to facilitate inputs, or through targeted efforts at supporting domestic linkages to foreign firms in SEZs.

DIGITAL INVESTMENT POLICIES AND MEASURES

Attracting inward FDI in the digital economy is one way to increase digital competitiveness in a rapidly digitalizing world (Ciuriak & Ptashkina, 2019). Estimates suggest that, by 2022, over 60% of global GDP would be digitized; yet, coping with COVID-19 will only accelerate and deepen this trend (IDC, 2018). At the same time, 50% of the world’s population does not participate in the digital economy (WEF, 2019b) and, by 2040, there will be a funding shortfall of nearly $1 trillion for information and communications technology infrastructure, holding back not only SDG 9 but also those SDGs that are enabled through infrastructure, which is virtually all others (Oxford Economics and Global Infrastructure Hub, 2018).

Yet, attracting FDI in the digital economy requires specific policies and measures. Digital firms have business models that differ from traditional bricks-and-mortar businesses. Digital firms rely heavily on data and technology, involve platform economies, and leverage non-traditional assets. Building on a conceptual framework laid out by UNCTAD, enabling policies, regulations, and measures may be thought of as falling in three areas (UNCTAD, 2017):

-

1.

Enabling investment in digital firms: For instance, policies and measures that encourage investment in ridesharing apps, such as the billions being invested in Gojek and Grab as they compete for the ridesharing and delivery market in Southeast Asia (Lee, 2020; Lunden, 2019).

-

2.

Enabling digital adoption by traditionally non-digital firms: For instance, policies and measures that encourage investment in telemedicine, mobile banking, or online sales, such as Walmart’s investment in India’s Flipkart to provide online sales (Walmart, 2018).

-

3.

Enabling investment in digital infrastructure: For instance, policies and measures that encourage investment in payment processors, such as Visa’s investment in Nigeria’s Interswitch, a payment switch and processing company, making Interswitch a unicorn overnight (Bright, 2019).

Within each of these three areas, there are specific policies, regulations, and measures that affect a potential investor’s decision to commit capital and other resources. The question then arises: what is important to an investor’s decision-making? For example, do data localization requirements affect investment in digital firms and activities? Do taxes on digital goods and services affect digital adoption in traditionally non-digital sectors? Does the use of international standards affect investment in digital infrastructure?

A new Digital FDI initiative seeks to identify the relative priority and importance of different policies and measures, as a first step through a survey of executives in 310 leading technology firms (Stephenson, 2020). This can help governments prioritize and sequence policies and measures as well as prioritize areas of dialogue and potential cooperation among economies with different regulatory visions. The survey revealed the top elements that investors care about across the three areas:

-

1.

When considering investing in digital firms: (a) data security regulations, (b) copyright laws to protect intellectual property, and (c) data privacy regulations.

-

2.

When considering investing in digital adoption: (a) availability of e-payment services, (b) support for starting digital businesses, and (c) support for local digital skills development.

-

3.

When considering investing in digital infrastructure: (a) ease of receiving licenses, (b) availability of skilled local engineers and other workers, and two elements tied for third place, (c) use of international standards and (d) regional coordination for infrastructure investment.

Full survey findings can be found in a white paper that also outlines how countries can tap into findings to drive domestic digital reform agendas (Stephenson, 2020). These findings may be especially important in the context of economic downturns, where facilitating digital investment may be one of the ladders to at once climb out of recession and support future resilience. Strikingly, the word ‘digital’ does not appear once in the SDGs, their targets, or their indicators. And yet, it is clear that the Fourth Industrial Revolution has profound implications on sustainable development (Herweijer et al., 2020). As a result, this calls for targeted efforts to tap into the new potentials of the digital economy to not only support – but accelerate – reaching the SDGs.

CREATE PARTNERSHIPS AND INDUSTRY-BASED COALITIONS

Creating partnerships and industry-based coalitions can be a useful mechanism to enact rapid, transformative change in pursuit of sustainable and digital investment. Partnerships are critical to realizing the SDGs, as recognized by both the fifth basic Principle of the SDGs (Partnering) and SDG 17, which is fully dedicated to promoting partnerships (van Zanten & van Tulder 2018).

Such coalitions would bring together policymakers, firms, and experts with specialized knowledge and the interest to drive positive change. Such specialized groups are effective because they have a better understanding of the operational challenges – and potential solutions – facing each industry. Thus, they can shape and advise on, inter alia, industry standards, cooperation opportunities, and trade and investment policies. They can also identify and implement specific development goals in their industry, in support of the SDGs.

There is therefore space for both sector-specific partnerships and policies as well as cross-sectoral partnerships and policies. The task for policymakers will be “to align policies to industries, and within those industries to relevant frontrunners that are willing to include these particular SDGs in their strategic planning and make them part of their core business through partnerships” (van Zanten & van Tulder, 2018: 19). This will allow for more targeted and precise interventions for policies to drive corporate behavior at the sectoral and industry level.

Industry-based coalitions can also suggest needed industry or product-based policies. With increasing specialization of firms that plug into complex global value chains, policies that target specific products and services may accelerate and deepen their contribution to development and digitization. For instance, standards at the industry level that do not consider the standards at the product level may fail to adequately facilitate trade and investment flows related to that product. This could forego some of the potential benefits of investment to help achieve sustainable development. Instead, two-way partnership between firms and governments can help ensure that sustainability-driving innovations and approaches are not left off the table.

Finally, partnerships and coalitions will also allow for coordination to align and unlock sources of finance and tackle the growing financing gap to the SDGs (see Introduction).

CONCLUSION

FDI fell by 49% in the first half of 2020 on account of the COVID-19 pandemic. This decline is alarming, as the world needs such investment not only for economic recovery, but also for long-term sustainable growth. This article presents five actionable steps to help restart investment flowing.

First, establish an Investment Facility and Fund. This would help create both the structure and the resources needed to restart investment flows. In particular, the Facility can support technical assistance for developing countries (and especially the least developed among them), as well as public–private collaboration, to tackle investment bottlenecks and limiting factors.

Second, ensure that the work of the Facility is implemented within a Sustainable Investment Framework, which will help facilitate collaboration and alignment among the efforts of different actors.

Third, adopt specific investment policies and measures to advance sustainable development, especially through linkages between foreign affiliates and domestic firms – which is a key mechanism for investment to contribute to sustainable development.

Fourth, adopt specific investment policies and measures to advance digital development, including through supporting investment in digital infrastructure, digital firms, and digital adoption by traditionally non-digital actors.

Fifth, use partnerships and industry-based coalitions as a mechanism to operationalize the above, tapping into the specificities and needs of different industries and unlocking greater SDG financing.

Together, the above five actions can increase investment flows in a way that helps achieve the SDGs during this ‘Decade of Action’ (Guterres, 2019).

REFERENCES

Alfaro, L., Holger, G., & Seric, A. 2017. Introduction to the symposium: Attracting and benefitting from Quality FDI. Review of World Economics, 153: 627–628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10290-017-0296-y.

Amendolagine, V., Boly, A., Coniglio, N., Prota, F., & Seric, A. 2013. FDI and local linkages in developing countries: Evidence from Sub-Saharan Africa. World Development, 50: 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.05.001.

Amendolagine, V., Presbitero, A., Rabellotti, R., Sanfilippo, M, & Seric, A. 2017. FDI, Global Value Chains, and Local Sourcing in Developing Countries. IMF Working Paper, WP/17/284. December 2017. https://www.imf.org/~/media/Files/Publications/WP/2017/wp17284.ashx.

Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) and United Nations (UN). 2010. How to Create and Benefit from Foreign Affiliate – Domestic SME Linkages: Lessons from Malaysia and Singapore, Best Practices in Investment for Development Case Studies in FDI. May 2010. https://www.apec.org/-/media/APEC/Publications/2010/5/Best-Practices-in-Investment-for-Development-Case-Studies-in-FDI-How-to-Create-and-Benefit-from-Fore/210_cti_ieg_FDI_smelinks.PDF

Balistreri, E. J., Berger, A., & Olekseyuk, Z. 2020. Economic effects of a potential investment facilitation framework at the World Trade Organization. Briefing Paper 2020, Bonn: German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE).

Berger, A., Ghouri, A., Ishikawa, T., Sauvant, K. P., & Stephenson, M. 2019. Toward G20 Guiding Principles on Investment Facilitation for Sustainable Development. T20 Japan, Task Force on Trade, Investment and Globalization. Accessed August 2020. https://t20japan.org/policy-brief-g20-guiding-principles-investment-facilitation/.

Bhattacharya, A., Gallagher, K. P., Cabré, M. M., Jeong, M., & Ma, X. 2019. Aligning G20 Infrastructure Investment with Climate Goals and the 2030 Agenda. Foundations 20 Platform, a report to the G20. Accessed August 2020. https://www.foundations-20.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/F20-report-to-the-G20-2019_Infrastrucutre-Investment.pdf.

Bhattacharya, A., & Jeong, M. 2018. Driving the Sustainable Infrastructure Agenda in Emerging Markets. Global Economy and Development at Brookings Institution, Working Paper, 2018. https://economic-policy-forum.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/GIZ-paper-20180630_final.pdf.

Bhattacharya, A., Oppenheim, J., & Stern, N. 2015. Driving Sustainable Development Through Better Infrastructure: Key elements of a transformation program. Global Economy and Development at Brookings Institutions, Working Paper 91, 2015. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/07-sustainable-development-infrastructure-v2.pdf.

Bright, J. 2019. Nigeria’s Interswitch confirms $1B valuation after Visa investment. TechCrunch. November 12, 2019. https://techcrunch.com/2019/11/11/nigerias-interswitch-confirms-1b-valuation-after-visa-investment/.

Buzdugan, S. R., & Tuselmann, H. 2018. Making the most of FDI for development: ‘New’ industrial policy and FDI deepening “for Industrial Upgrading. Transnational Corporations, 25(1): 1–21.

Casella, B., & Formenti, L. 2019. FDI in the digital economy: A shift to asset-light international footprints. Transnational Corporations, 25(1): 101–130.

Chen, L., Cheng, W. Ciuriak, D., Kimura, F., Nakagawa, J, Pomfret, R., Rigoni, G., & Schwarzer, J. 2019. The Digital Economy for Economic Development: Free Flow of Data and Supporting Policies. T20 Japan, Task Force on Trade, Investment and Globalization. Accessed August 2020. https://t20japan.org/policy-brief-digital-economy-economic-development/.

China Chamber of Commerce of Metals Minerals & Chemicals Importers & Exporters. 2015. Chinese Due Diligence Guidelines for Responsible Mineral Supply Chains. Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China. 2015. Accessed August 2020. https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/chinese-due-diligence-guidelines-for-responsible-mineral-supply-chains.htm.

Ciuriak, D. 2019. Economic Rents and the Contours of Conflict in the Data-Driven Economy. Accessed August 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3496025.

Ciuriak, D, & Ptashkina, M. 2019. A Global South Strategy to Leverage the Digital Transformation for Development. Accessed August 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3405330.

European Union (EU). 2017. Regulation (EU) 2017/821 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 May 2017 Laying Down Supply Chain Due Diligence Obligations for Union Importers of Tin, Tantalum and Tungsten, their Ores, and Gold Originating from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas. Accessed August 2020. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32017R0821.

Evenett, S. J. 2020. Chinese whispers: COVID-19, global supply chains in essential goods, and public policy. Journal of International Business Policy, 3(4): 408–429. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-020-00075-5.

Gaspar, V., Amaglobeli, D., Garcia-Escribano, M., Prady, D., & Soto, M. 2019. Fiscal Policy and Development: Human, Social, and Physical Investment for the SDGs. IMF Staff Discussion Note SDN 19/03, 23 January 2019. Accessed 24 November 2020. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Staff-Discussion-Notes/Issues/2019/01/18/Fiscal-Policy-and-Development-Human-Social-and-Physical-Investments-for-the-SDGs-46444.

Glauber, J., Laborde, D., Martin, W., & Vos, R. 2020. COVID-19: Trade Restrictions are Worst Possible Response to Safeguard Food Security. IFFRI Blog Issue Post. March 27, 2020. https://www.ifpri.org/blog/covid-19-trade-restrictions-are-worst-possible-response-safeguard-food-security.

Global Trade Alert. 2010. Tackling COVID-19 Together: The Trade Policy Dimension. March 23, 2020. https://www.globaltradealert.org/reports/51.

Government of India. n.a. National CSR Data Portal. Accessed March 31, 2020. https://vikaspedia.in/e-governance/online-citizen-services/government-to-citizen-services-g2c/national-csr-data-portal.

Government of South Africa Department of Trade and Industry. 2016. Guidelines for Good Business Practice by South African Companies Operating in the Rest of Africa. Accessed August 2020. https://www.rmi.org.za/guidelines-for-good-business-practice-by-south-african-companies-operating-in-the-rest-of-africa/.

Guterres, A. 2019. Remarks to High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development. 24 September 2019, United Nations Secretary General. https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/speeches/2019-09-24/remarks-high-level-political-sustainable-development-forum.

Herweijer, C., Combes, B., Gawel, A., Engtoft Larsen, A. M., Davies, M., Wrigley, J., & Donnelly, M. 2020. Unlocking Technology for the Global Goals. January 2020, World Economic Forum and PwC. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/Unlocking_Technology_for_the_Global_Goals.pdf.

International Data Corporation (IDC). 2018. By 2023 Nearly Every Enterprise Will Be ‘Digital Native’ in an Increasingly Digitized Global Economy. Accessed August 2020. https://technologies.org/by-2023-nearly-every-enterprise-will-be-digital-native-in-an-increasingly-digitized-global-economy/.

International Labour Organization (ILO). 2017. Tripartite Declaration of Principles Concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy. Accessed August 2020. https://www.ilo.org/empent/areas/mne-declaration/lang–en/index.htm.

Lee, Y. 2020. Ride-Hailing Giant Gojek Raises $1.2 Billion for Clash with Grab. Bloomberg. March 17, 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-17/ride-hailing-giant-gojek-raises-1-2-billion-for-clash-with-grab.

Lunden, I. 2019. SoftBank Pumps $2B into Indonesia through Grab Investment, Putting it Head to Head with Gojek. TechCrunch. July 29, 2019. https://techcrunch.com/2019/07/29/softbank-pumps-2b-into-indonesia-through-new-grab-investment-putting-it-head-to-head-with-gojek/?guccounter=1.

Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA). 2013. Policy on Environmental and Social Sustainability. October 1, 2013. https://www.miga.org/sites/default/files/archive/Documents/Policy_Environmental_Social_Sustainability.pdf.

Moran, T. H., Görg H., & Seric, A. 2016. Quality FDI and Supply-Chains in Manufacturing: Overcoming Obstacles and Supporting Development. Kiel Centre for Globalization, KCG Policy Papers 1. Accessed August 2020. https://ideas.repec.org/p/zbw/kcgpps/1.html.

New Climate Economy, The. 2016. The Sustainable Infrastructure Imperative: Financing for Better Growth and Development. The 2016 New Climate Economy Report. Global Commission on the Economy and Climate. Accessed August 2020. http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/file/NCE_2016Report.pdf.

OECD-FAO. 2016. OECD-FAO Guidance for Responsible Agricultural Supply Chains. Accessed August 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264251052-en.

OECD-UNIDO. 2019. Integrating Southeast Asian SMEs in Global Value Chains: Enabling Linkages with Foreign Investors. Accessed August 2020. https://www.oecd.org/investment/Integrating-Southeast-Asian-SMEs-in-global-value-chains.pdf.

OECD-WBG-UN Environment. 2018. Financing Climate Futures: Rethinking Infrastructure. Accessed August 2020. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264308114-en.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2011. Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises. Accessed August 2020. http://mneguidelines.oecd.org/guidelines/.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2016a. Development Co‐operation Report 2016: The Sustainable Development Goals as Business Opportunities. Accessed August 2020. https://www.oecd.org/dac/development-co-operation-report-2016.htm.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2016b. OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas. Accessed August 2020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264252479-en.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2019. FDI Qualities Indicators: Measuring the Sustainable Development Impacts of Investment. Accessed August 2020. www.oecd.org/fr/investissement/fdi-qualities-indicators.htm.

Omic, A., & Stephenson, M. 2019. What Can Governments do to Facilitate Investment? Important Measures Identified Through Surveys. World Economic Forum and World Association of Investment Promotion Agencies. Accessed August 2020. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Investment_Facilitation_2019.pdf.

Oxford Economics and Global Infrastructure Hub. 2018. Global Infrastructure Outlook: Investment need in the Compact with Africa countries. Accessed 24 November 2020. https://www.gihub.org/sectors/communications/.

Perea, J. R., & Stephenson, M. 2018. Outward FDI from Developing Countries. Global Investment Competitiveness Report 2017/2018: Foreign Investor Perspectives and Policy Implications. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://elibrary.worldbank.org/doi/full/10.1596/978-1-4648-1175-3_ch4.

Sachs, J., Schmidt-Traub, G., Kroll, C., Lafortune, G., Fuller, G., & Woelm, F. 2020. The Sustainable Development Goals and COVID-19. Sustainable Development Report 2020. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://s3.amazonaws.com/sustainabledevelopment.report/2020/2020_sustainable_development_report.pdf.

Sauvant, K. P. 2020. A G20 Facility to Rekindle FDI Flows. Columbia FDI Perspective 278. Accessed August 2020. http://ccsi.columbia.edu/files/2020/05/No-278-Sauvant-FINAL.pdf.

Sauvant, K. P., & Gabor, E. 2019. Advancing Sustainable Development by Facilitating Sustainable FDI, Promoting CSR, Designating Recognized Sustainable Investors, and Giving Home Countries a Role. Accessed August 2020. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3496967 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3496967.

Sauvant, K. P., & Mann, H. 2017. Towards an Indicative List of FDI Sustainability Characteristics. Geneva: ICTSD and WEF. Accessed August 2020. http://e15initiative.org/publications/towards-an-indicative-list-of-fdi-sustainability-characteristics/.

Stephenson, M. 2018. Investment as a two-way street: How China used inward and outward investment policy for structural transformation, and how this paradigm can be useful for other emerging economies. PhD Dissertation Number 1252, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies, Geneva, Switzerland. https://repository.graduateinstitute.ch/record/295767?ln=en.

Stephenson, M. 2020. Digital FDI: Policies, regulations and measures to attract FDI in the digital economy. White Paper, World Economic Forum, September 2020. https://weforum.box.com/s/9wpwwc9kwmjcudc768c3i6vnkms4847n.

United Nations (UN). 2011. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. HR/PUB/11/04. Accessed August 2020. https://www.ohchr.org/documents/publications/guidingprinciplesbusinesshr_en.pdf.

United Nations (UN). 2020a. Financing for Sustainable Development Report 2020. Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development. Accessed 24 November 2020. https://developmentfinance.un.org/sites/developmentfinance.un.org/files/FSDR_2020.pdf.

United Nations (UN). 2020b. Global indicator framework for the Sustainable Development Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Accessed 26 November 2020. https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators/Global%20Indicator%20Framework%20after%202020%20review_Eng.pdf.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2014. World Investment Report 2014: Investing in the SDGs – An Action Plan. Accessed August 2020. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2014_en.pdf.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2015. Investment Policy Framework for Sustainable Development. Accessed August 2020. https://unctad.org/en/pages/PublicationWebflyer.aspx?publicationid=1437.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2017. World Investment Report 2017: Investment and the Digital Economy. Accessed August 2020. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wir2017_en.pdf.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2019. Taking Stock of II Reform: Recent Developments. IIA issue Note. Accessed August 2020. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/diaepcbinf2019d5_en.pdf.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2020. Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Global FDI and GVCs. Investment Trends Monitor. Accessed August 2020. https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/diaeiainf2020d3_en.pdf.

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). 2016. Sustainable Infrastructure and Finance: How to Contribute to a Sustainable Future. Inquiry Working Paper. Accessed August 2020. http://wedocs.unep.org/handle/20.500.11822/7756.

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP). 2017. Handbook on Policies, Promotion and Facilitation of Foreign Direct Investment for Sustainable Development in Asia and Pacific. United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific. Accessed August 2020. https://www.unescap.org/resources/handbook-policies-promotion-and-facilitation-foreign-direct-investment-sustainable-0.

United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO). 2018. Global Value Chains and Industrial Development: Lessons from China, South-East and South Asia. United Nations Industrial Development Organization. Accessed August 2020. https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/files/2018-06/EBOOK_GVC.pdf.

United States Securities and Exchange Commission. 2012. 17 CFR PARTS 240 and 249b [Release No. 34-67716; File No. S7-40-10] RIN 3235-AK84 CONFLICT MINERALS AGENCY. Accessed August 2020. https://www.sec.gov/rules/final/2012/34-67716.pdf.

van Tulder, R. 2018. Business & the sustainable development goals: A framework for effective corporate involvement. Rotterdam: Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University.

van Zanten, J. A., & van Tulder, R. 2018. Multinational enterprises and the Sustainable Development Goals: An institutional approach to corporate engagement. Journal of International Business Policy, 1: 208–233. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-018-0008-x.

van Zanten, J. A., & van Tulder, R. 2020. Beyond COVID-19: Applying ‘‘SDG logics’’ for resilient transformations. Journal of International Business Policy, 3(4): 451–464. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-020-00076-4.

Walmart. 2018. Walmart to Invest in Flipkart Group, India’s Innovative eCommerce Company. Accessed August 2020. https://corporate.walmart.com/newsroom/2018/05/09/walmart-to-invest-in-flipkart-group-indias-innovative-ecommerce-company.

World Bank Group (WBG). 2018. World Bank Group Launches New Multi-Donor Fund in Support of SDG Implementation. October 18, 2018. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2018/10/18/world-bank-group-launches-new-multi-donor-fund-in-support-of-sdg-implementation.

World Bank Group (WBG). 2020. Global Investment Competitiveness Report 2019/2020: Rebuilding Investor Confidence in Times of Uncertainty. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33808.

World Bank Group (WBG). n.a. Support Program for Investment Reform and Innovative Transformation. Undated. Accessed March 31, 2020. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/594381510251482638/SPIRIT-Toolkit.pdf.

World Economic Forum (WEF). 2019a. Five Dimensions of Sustainable Investment. Accessed August 2020. https://weforum.box.com/s/yrin498t6dtbtrhq8x4isbc0y43f7rol.

World Economic Forum (WEF). 2019b. Shaping the Future of Digital Economy and New Value Creation. Accessed August 2020. https://www.weforum.org/platforms/shaping-the-future-of-digital-economy-and-new-value-creation.

World Economic Forum (WEF). 2020. Toward Common Metrics and Consistent Reporting of Sustainable Value Creation. White Paper. Accessed August 2020. https://www.weforum.org/whitepapers/toward-common-metrics-and-consistent-reporting-of-sustainable-value-creation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This paper builds on a policy brief entitled “How the G20 can advance sustainable and digital investment” prepared for the T20 Task Force on Trade, Investment, and Growth (2020). The authors wish to thank two anonymous referees and Anabel Gonzalez, Resident Senior Fellow, Peterson Institute for International Economics, for their input and guidance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Accepted by Rob Van Tulder, Area Editor, 19 December 2020. This article has been with the authors for one revision and was single-blind reviewed.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Dimension | Elements | Tools | Actors | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Sustainable investment policies | International law, national law, international process standards, national process standards, and industry process standards | IIAs, OECD Guidelines, firm-level CSR guidelines, domestic labor codes, Environmental and Social Impact Assessments, supply-chain guidelines for mining or for agriculture | Policies can apply to both host governments and home governments, as well as host firms and home firms | Sustainable investment requires investment to take place in the context of respect for human rights, health and safety standards, social and environmental protection, and respect for core labor rights; policies can encompass both “carrots” and “sticks” |

Sustainable finance mobilization | Corporate sustainability ratings, financial standards, and corporate sustainability reporting | Sustainability Accounting Standards (SASB), Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), Sustainable stock exchange initiative | Sustainable finance mobilization is mainly targeted to firms, whether portfolio investors, institutional investors, impact investors, and sustainable investors | Sustainable investment requires stakeholders to have information regarding the sustainability behavior of different firms for policymakers, regulators, investors, media, and civil society to reward or punish investment behavior through incentives and sanctions, thus providing market signals to better align market mechanisms with SDG goals |

Sustainable investment promotion | National strategy for attracting investment, targeted promotion to SDG sectors, and targeted promotion to sustainable investors | Recognized Sustainable Investor (RSI) measure, behavioral incentives, home-country measures conditional on sustainability performance, pipeline of bankable projects, promotion campaigns, roadshows, investment conferences | Host economy IPA, home economy IPA, other policymakers, host economy firms, and home economy firms | Sustainable investment can be furthered through (a) targeting investors in sectors that are particularly conducive to the SDGs, (b) targeting investors with a sustainability mission, and (c) creating a pipeline of sustainable bankable projects |

Sustainable investment facilitation | Administrative procedures and requirements, transparency, aftercare, quality standards, and insurance | Focal point, One-stop shop, ombudsperson, lists of domestic suppliers, guarantees and insurance targeted to support and protect sustainable investment | Host economy IPA, home economy IPA, other policymakers, insurance providers, host economy firms, and home economy firms | Sustainable investment can be furthered through providing greater facilitation services and support to investment that is aligned with sustainable development goals of the economy; this can be facilitated by partnership between home and host IPAs, as well as regional cooperation |

Sustainable development impact | Business linkages, training, technology transfer, indicators, and stakeholder engagement | PPPs, supplier-development program to create linkages, SEZs focused on SDGs, OECD FDI qualities indicators, UNESCAP FDI indicators, firm reporting on ESG impact, and public–private dialogues | Host economy IPA, home economy IPA, other policymakers, civil society, international organizations, development institutions, and donor governments | Sustainable investment also involves programs and initiatives to maximize positive development effects and minimize potential negative effects by increasing the absorptive capacity in economies, tools to measure sustainable impact, stakeholder engagement, public scrutiny and pressure, and making trade-offs |

Appendix 2

SDG 1 | |

Target 1.b | Create sound policy frameworks at the national, regional and international levels, based on pro-poor and gender-sensitive development strategies, to support accelerated investment in poverty eradication actions |

SDG 2 | |

Target 2.a | Increase investment, including through enhanced international cooperation, in rural infrastructure, agricultural research and extension services, technology development and plant and livestock gene banks in order to enhance agricultural productive capacity in developing countries, in particular least developed countries |

SDG 7 | |

Target 7.a | By 2030, enhance international cooperation to facilitate access to clean energy research and technology, including renewable energy, energy efficiency and advanced and cleaner fossil-fuel technology, and promote investment in energy infrastructure and clean energy technology |

SDG 10 | |

Target 10.b Indicator 10.b.1 | Encourage official development assistance and financial flows, including foreign direct investment, to States where the need is greatest, in particular least developed countries, African countries, small island developing States and landlocked developing countries, in accordance with their national plans and programmes Total resource flows for development, by recipient and donor countries and type of flow (e.g., official development assistance, foreign direct investment and other flows) |

SDG 17 | |

Target 17.5 Indicator 17.3.1 Indicator 17.5.1 | Adopt and implement investment promotion regimes for least developed countries Foreign direct investment, official development assistance and South–South cooperation as a proportion of gross national income Number of countries that adopt and implement investment promotion regimes for developing countries, including the least developed countries |

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Stephenson, M., Hamid, M.F.S., Peter, A. et al. More and better investment now! How unlocking sustainable and digital investment flows can help achieve the SDGs. J Int Bus Policy 4, 152–165 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-020-00094-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s42214-020-00094-2