Abstract

Almost all governments issue large stocks of debt. Optimal taxation theory typically concludes that they should hold large stocks of assets. To reconcile facts and theory, we introduce two simple modifications into an otherwise standard optimal taxation model with commitment: government impatience and continuous debt limits. Two results are obtained. First, positive government debt is optimal for even minimal government impatience. Second, the optimality of negative government debt disappears even without impatience if discrete debt limits are replaced by very wide but continuous debt limits. We go on to quantify the implications for debt, interest rates and business cycle dynamics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Chari and Kehoe (1999) for a review of this literature.

It is also possible to argue, although in the absence of more detailed empirical evidence we do not wish to take a stand on this, that the “neoliberal consensus,” or the “end of history” in the sense of Fukuyama (1992), has been characterized by a considerable narrowing of this heterogeneity among policymakers over the sample period that we consider.

The optimal taxation literature generally treats government spending as exogenous (and wasteful in terms of household utility) because of its acyclical or mildly procyclical nature in the data. Paquet and Ambler (1994) concluded that endogenizing government spending would imply that public spending would closely mimic private spending and would therefore overpredict the correlation of public spending with output.

The negative government debt result of Aiyagari and others (2002) is based on a specific set of parameter values. Their paper does not discuss the generality of that result and its sensitivity to parameter values.

To make complete markets problems more interesting, this is typically ruled out through an ad hoc restriction on the initial tax rate on debt.

What matters in theses models is that households discount the future at a higher rate than the market real interest rate, as this literature does not specify a government objective function. This is because its applications typically do not deal with optimal policy issues.

Relative to Aiyagari and others (2002), replacing a discrete debt limit by a continuous debt limit also reduces the government’s incentives for precautionary saving.

As discussed in the introduction, the literature has suggested to interpret such costs as monitoring and administrative costs that depend on the stock of debt (or assets) outstanding.

In the open economy literature, which frequently uses this type of transactions cost, the assumption of lump-sum redistribution is also standard.

Post-crisis levels of debt are far higher, and levels of real interest rates are far lower, reflecting a number of exceptional circumstances that are not captured by our simple model. We only consider post-crisis data in two cases where the sample period would otherwise have been too short for meaningful econometric results.

This parameter depends on one’s benchmark value for the proportion of time spent working in steady state. King and Rebelo (1999), in a business cycle model without distorting taxes, set \(\kappa =3.48\), but values lower than 3 can also be justified on that basis.

We note that this excludes government transfer payments.

We did not change this ratio across countries, so that calibrated steady-state tax revenue-to-GDP ratios are more similar across countries than they are in the data. There are three reasons for this choice. First, it makes comparison across different calibrations of γ and ϕ easier. Second, our model features only labor income taxes, while overall tax revenue has many other components that are not present in our model. And third, tax revenues to GDP ratios are not only determined by the level of government spending but also by the level of transfers, which are not present in our model.

It can be shown that when positive steady-state growth is added to the model, the main difference is an increase in the steady-state real interest rate that is approximately equal to the real growth rate, with all other aspects of the steady state broadly unchanged.

As we will see, in a modified Ramsey equilibrium the deterministic and stochastic steady states are close to each other.

OECD (2007) reports 2006 ratios of government gross financial liabilities to GDP of 77.1 percent for the OECD average and 61.9 percent for the U.S.

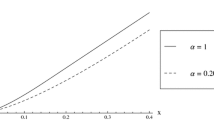

Let the gross rate of time preference be denoted by \(\tilde{\beta }=1/\beta\). Then Eq. (23) can be rewritten as \(r=\tilde{\beta }/\left( 1- \tilde{\beta }\frac{\phi }{4}\frac{b}{\ell }\right)\). The net real interest rate is approximately given by \(r^{n}=log(r)\). For small values of ϕ, and for \(\tilde{\beta }\simeq 1\), the derivative \(dr^{n}/d\left( \frac{b}{ 4\ell }\right)\) of this expression is approximately equal to ϕ.

Exceptions: Belgium GDP 1992Q1–2007Q4 and Chile real interest rate 1995Q2–2007Q4.

For the latter two, data for 2008–2015 are only used for unit root tests, to overcome sample size limitations, especially for labor taxes.

The definition of the tax wedge in OECD (2016) is: “The tax wedge is defined as the ratio between the amount of taxes paid by an average single worker (a single person at 100 percent of average earnings) without children and the corresponding total labor cost for the employer. The average tax wedge measures the extent to which tax on labor income discourages employment. This indicator is measured in percentage of labor cost.”

The rule is described in detail in Marcel and others (2001).

Available at http://pythie.cepremap.cnrs.fr/mailman/listinfo/dynare.

The main difference is that according to the third-order approximation the real interest rate exhibits a higher serial correlation (0.52 instead of 0.43) and a stronger negative correlation with GDP (−0.71 instead of −0.65).

The transition to the stochastic steady state, computed using a global method and based on a particular history of shocks, exhibits similar behavior. See the working paper version of this paper (Kumhof and Yakadina 2007).

The latter may be the main reason why debt-to-GDP ratios in developing countries are often comparatively low, see Reinhart and others (2003), which is related to our discussion of Chile above.

Note that in each of the subplots, we shut down the shock whose serial correlation is not shown along the horizontal axis.

The statistic cannot be computed for the Chilean tax wedge, which was constant at 7 percent throughout the entire sample period.

References

Aguiar, M., and M. Amador, 2011, “Growth in the Shadow of Expropriation,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 126, pp. 651–697.

Aguiar, M., and M. Amador, 2015, “Fiscal Policy in Debt-Constrained Economies,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Research Department Staff Report No. 518.

Aiyagari, R., 1995, “Optimal Capital Income Taxation with Incomplete Markets, Borrowing Constraints, and Constant Discounting,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 103, No. 6, pp. 1158–1175.

Aiyagari, R., A. Marcet, T. J. Sargent, and J. Seppälä, 2002, “Optimal Taxation without State-Contingent Debt,” Journal of Political Economy , Vol. 110, No. 6, pp. 1220–1254.

Aiyagari, R., and E. R. McGrattan, 1998, “The Optimum Quantity of Debt,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 42, pp. 447–469.

Alesina, A., and G. Tabellini, 1990, “A Positive Theory of Fiscal Deficits and Government Debt,” Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 57, pp. 403–414.

Azzimonti, M., 2011, “Barriers to Investment in Polarized Societies,” American Economic Review, Vol. 101, No. 5, pp. 2182–2204.

Azzimonti, M., 2015, “The Dynamics of Public Investment under Persistent Electoral Advantage,” Review of Economic Dynamics, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp. 653–678.

Barro, R. J., 1979, “On the Determination of Public Debt,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 87, No. 5, pp. 940–971.

Battaglini, M., and S. Coate, 2008, “A Dynamic Theory of Public Spending, Taxation and Debt,” American Economic Review, Vol. 98, No. 1, pp. 201–236.

Blanchard, O. J., 1985, “Debt, Deficits, and Finite Horizons,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 93, 223–247.

Chari, V. V., L. J. Christiano, and P. J. Kehoe, 1994, “Optimal Fiscal Policy in a Business Cycle Model,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 102, No. 4, pp. 617–652.

Chari, V. V., and P. J. Kehoe, 1999, “Optimal Fiscal and Monetary Policy,” in Handbook of Macroeconomics, ed. by J. B. Taylor and M. Woodford (North-Holland: Elsevier).

Debortoli, D., and R. Nuñes, 2013, “Lack of Commitment and the Level of Debt,” Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 11, pp. 1053–1078.

Engen, E. M., and R. G. Hubbard, 2004, “Federal Government Debt and Interest Rates,” NBER Macroeconomics Annual, Vol. 19, pp. 83–138.

Farhi, E., and I. Werning, 2007, “Inequality and Social Discounting,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 115, No. 3, pp. 365–402.

Fukuyama, F., 1992, The End of History and the Last Man (New York: Free Press).

Gale, W. G., and P. R. Orszag, 2003, “Economic Effects of Sustained Budget Deficits,” National Tax Journal, Vol. 56, No. 3, pp. 463–485.

Gale, W., and P. Orszag, 2004, “Budget Deficits, National Saving, and Interest Rates,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Vol. 2, pp. 101–187.

Grossman, H. I., and J. B. van Huyck, 1988, “Sovereign Debt as a Contingent Claim: Excusable Default, Repudiation, and Reputation,” American Economic Review, Vol. 78, No. 5, pp. 1088–1097.

Heaton, J., and D. Lucas, 1996, “Evaluating the Effects of Incomplete Markets on Risk Sharing and Asset Pricing,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 104, No. 3, pp. 443–487.

King, R. G., and S. T. Rebelo, 1999, “Resuscitating Real Business Cycles,” in Handbook of Macroeconomics, ed. by J. B. Taylor and M. Woodford (North-Holland: Elsevier).

Kumhof, M., and I. Yakadina, 2007, “Politically Optimal Fiscal Policy,” IMF Working Paper 07/68, (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

Laubach, T., 2009, “New Evidence on the Interest Rate Effects of Budget Deficits and Debt,” Journal of the European Economic Association, Vol. 7, No. 4, pp. 858–885.

Lucas, R. E. Jr., 1987, Models of Business Cycles (Oxford, New York: Basil Blackwell).

Lucas, R. E. Jr., and N. Stokey, 1983, “Optimal Fiscal and Monetary Policy in an Economy without Capital,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 12, pp. 55–93.

Marcel, M., M. Tokman, R. Valdés, and P. Benavides, 2001, “Balance Estructural: La Base de la Nueva Regla de Polí tica Fiscal Chilena,” Economía Chilena, Vol. 4, No. 3, pp. 5–27.

Marcet, A., and R. Marimon, 1998, “Recursive Contracts,” Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Economics Working Paper No. 337.

Martin, F. M., 2009, “A Positive Theory of Government Debt,” Review of Economic Dynamics, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 608–631.

Neumeyer, P., and F. Perri, 2005, “Business Cycles in Emerging Economies: The Role of Interest Rates,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol. 52, pp. 345–380.

OECD, 2007, OECD Economic Outlook (Paris: OECD Publishing).

OECD, 2016, Taxing Wages (Paris: OECD Publishing).

Paquet, A., and S. Ambler, 1994, “Fiscal Spending Shocks, Endogenous Government Spending, and Real Business Cycles,” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Discussion Paper No. 94.

Persson, T., and L. Svensson, 1989, “Why a Stubborn Conservative Would Run a Deficit: Policy with Time-Inconsistent Preferences,” Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 104, pp. 325–346.

Phelan, C., 2006, “Opportunity and Social Mobility,” Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 73, No. 2, pp. 487–504.

Reinhart, C. M., K. S. Rogoff, and M. A. Savastano, 2003, “Debt Intolerance,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, pp. 1–74.

Reiter, M., 2005, “Solving Models of Optimal Monetary and Fiscal Policy by Projection Methods,” Working Paper, Universitat Pompeu Fabra.

Schmitt-Grohe, S., and M. Uribe, 2003, “Closing Small Open Economy Models,” Journal of International Economics, Vol. 61, pp. 163–185.

Schmitt-Grohe, S., and M. Uribe, 2004, “Optimal Fiscal and Monetary Policy Under Sticky Prices,” Journal of Economic Theory, Vol. 114, pp. 198–230.

Shin, Y., 2006, “Ramsey Meets Bewley: Optimal Government Financing with Incomplete Markets,” Working Paper, University of Wisconsin.

Sleet, C., and S. Yeltekin, 2006, “Credibility and Endogenous Societal Discounting,” Review of Economic Dynamics, Vol. 9, pp. 410–437.

Tornell, A., and A. Velasco, 1995, “Fiscal Discipline and the Choice of Exchange Rate Regime,” European Economic Review, Vol. 39, pp, 759–770.

Tornell, A., and A. Velasco, 2000, “Fixed Versus Flexible Exchange Rates: Which Provides More Fiscal Discipline?,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vo. 45, pp. 399–436.

Woodford, M., 1999, “Commentary: How Should Monetary Policy Be Conducted in an Era of Price Stability?,” in New Challenges for Monetary Policy: A Symposium Sponsored by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Yaari, M. E., 1965, “Uncertain Lifetime, Life Insurance, and the Theory of the Consumer,” Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 32, pp. 137–150.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We are grateful to James Barker for excellent research assistance.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix: The Non-stochastic Steady State

Appendix: The Non-stochastic Steady State

We drop time subscripts to denote steady-state values of variables. The non-stochastic steady state of the economy is given by the system of five equations (11), (16), (19), (20) and (21) determining the variables \(c, \ell , b, \eta\) and \(\lambda\). Equations (19), (20) and (21) become

where we have combined (19) with (16). Consider the case of \(\lambda =0\). In that case, we would have \(\eta =1/c\) and \(\eta =\kappa /(1-\ell )\). Then by the consumer’s first-order condition (4), it would have to be true that \(\tau =0\). Such a case would only be possible in the first-best, which is only achievable if the government can accumulate a sufficient amount of assets to finance fiscal spending without any distortionary taxation. This is however ruled out in our model by condition (A3), which makes the steady-state debt stock positive. We can therefore rule out \(\lambda =0\). The remaining steady-state conditions are

In a first step, the steady-state values b, c and l can be solved from (A3), (A4) and (A5). In a second step, the remaining equations (A1) and (A2) then determine \(\lambda\) and \(\eta\). The first step results in the quadratic equation for \(\ell\)

where

There are therefore two possible solutions for steady-state labor, and by (A4) also for steady-state consumption. The roots of equation (A6) are given by

While both roots are positive for our parameterization, the smaller root implies a level of consumption very close to zero (\(c=0.0002\)) and a much lower welfare than the larger root. The smaller root can therefore be ruled out. This means that even for large fluctuations around the steady state, the use of a perturbation method that approximates the solution around the superior steady state remains appropriate.