Abstract

Several studies investigate the meanings of democracy among the adult population. In contrast, less is known about young citizens’ ideas of democracy, and which individual and contextual characteristics are associated with them. This article contributes to the literature by uncovering the meanings of democracy and their correlates among adolescents in 38 countries. Using the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study 2009, the article shows that meanings of democracy vary among adolescents. These meanings are the results of how adolescents find various aspects of democracy, as the rule of law, freedoms, rights, pluralism, or equality, constitutive of it. Then, the article assesses whether socialization agents and personal characteristics account for the different meanings of democracy to adolescents. Finally, the analysis addresses the role that larger contexts—democratization and human development—have in the formation of concepts of democracy among adolescents.

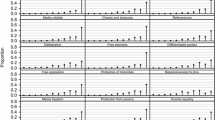

Source: own elaboration of ICCS 2009

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Unfortunately, with the available data it is not possible to test whether ideas of democracy among adolescents change over the life course.

According to this reasoning, it should be born in mind that the link between information and meanings of democracy to adolescents might be endogenous, as adolescents with more complex ideas of democracy might be more prone to look for political information. Unfortunately, given the research design, we cannot address this issue.

The list of countries is reported in the Supplementary materials.

Descriptive statistics and detailed descriptions of the variables are reported in the Supplementary materials.

While among the identified classes we can find three that be ordered (“limited”, “minimalist” and “complex”), we find also two (“free-speech” and “uncritical”) that cannot be fitted in an ordered scale. Do note that Latent Class Analysis finds groupings that are nominal, i.e. mutually exclusive classes with no natural order, thus presenting qualitative differences, rather quantitative ones. In this regard, Collins and Lanza (2010, p. 34) argue: “the subgroups revealed in LCA may not be ordered along a single quantitative dimension”. Nevertheless, in the Supplementary materials, multilevel ordinal models using the three orderable classes as dependent variable are presented. Results are comparable to those presented in this article, although they do not consider the additional two classes.

Looking at this response category allows capture of a solid endorsement for the elements of democracy and better differentiation among the respondents, given that the majority agree or strongly agree with the statements. It should be clear that the analysis was carried out on the ordinal items.

The coefficients of the model are reported in the Supplementary materials.

In this regard, also ideology or political values might be relevant factors for meanings of democracy as citizens emphasize the role of some elements of this type or regime depending on their political and social views, as shown by research on the adult population (e.g. Carlin and Singer, 2011; Ceka and Magalhães 2016). Unfortunately, we cannot control for this aspect in this study.

References

Abramson, P.R., and T.M. Hennessey. 1970. Beliefs about democracy among British adolescents. Political Studies 18 (2): 239–242.

Amnå, E. 2012. How is civic engagement developed over time? Emerging answers from a multidisciplinary field. Journal of Adolescence 35 (3): 611–627.

Andolina, M.W., K. Jenkins, C. Zukin, and S. Keeter. 2003. Habits from home, lessons from school: Influences on youth civic engagement. PS: Political Science and Politics 36 (2): 275–280.

Arensmeier, C. 2010. The Democratic common sense: Young swedes’ understanding of democracy – theoretical features and educational incentives. Young 18 (2): 197–222.

Baldi, S., M. Perie, D. Skidmore, E. Greenberg, C. Hahn, and D. Nelson. 2001. What Democracy Means to Ninth-Graders: U.S. Results from the International IEA Civic Education Study. Washington: U.S. Department of Education, Office of Educational Research and Improvement, National Center for Education Statistics.

Campbell, D.E. 2008. Voice in the classroom: How an open classroom climate fosters political engagement among adolescents. Political Behavior 30 (4): 437–454.

Carlin, R.E., and M.M. Singer. 2011. Support for polyarchy in the Americas. Comparative Political Studies 44 (11): 1500–1526.

Ceka, B., and P.C. Magalhães. 2016. How people understand democracy: A social dominance approach. In How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy, ed. M. Ferrin and H.-P. Kriesi, 90–110. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Collier, D., and S. Levitsky. 1997. Democracy with adjectives: Conceptual innovation in comparative research. World Politics 49 (3): 430–451.

Collins, L.M., and S.T. Lanza. 2010. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis: With Applications in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences. Hoboken: Wiley.

Dalton, R.J. 2009. The Good Citizen: How a Younger Generation is Reshaping American Politics. Washington: CQ Press.

Dalton, R.J., and C.J. Anderson (eds.). 2010. Citizens, Context and Choice. How Context Shapes Citizens’ Electoral Choices. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Delli Carpini, M.X. 1989. Age and history: Generations and socio-political change. In Political Learning in Adulthood, ed. R. Siegel, 11–56. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Delli Carpini, M.X., and S. Keeter. 1996. What Americans Know About Politics and Why it Matters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dinas, E. 2013. Opening “openness to change”: Political events and the increased sensitivity of young adults. Political Research Quarterly 66 (4): 868–882.

Dobson, A.J., and A.G. Barnett. 2008. An Introduction to Generalized Linear Models. Boca Raton: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

Ferrín, M., M. Fraile, and M. Rubal. 2015. Young and gapped? Political knowledge of girls and boys in Europe. Political Research Quarterly 68 (1): 63–76.

Ferrin, M., and H.-P. Kriesi (eds.). 2016. How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Flanagan, C.A. 2013. Teenage Citizens: The Political Theories of the Young. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Flanagan, C.A., P. Cumsille, S. Gill, and L.S. Gallay. 2007. School and community climates and civic commitments: Patterns for ethnic minority and majority students. Journal of Educational Psychology 99 (2): 421–431.

Flanagan, C.A., M.L. Martínez, and P. Cumsille. 2010. Civil societies as cultural and developmental contexts for civic identity formation. In Bridging Cultural and Developmental Approaches to Psychology: New Synthesis in Theory, Research and Policy, ed. L. Arnet Jensen, 116–137. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Flanagan, C.A., L.S. Gallay, S. Gill, E. Gallay, and N. Nti. 2005. What does democracy mean? Correlates of adolescents’ views. Journal of Adolescent Research 20 (2): 193–218.

Franklin, M., and P. Riera. 2016. Types of liberal democracy and generational shifts. In How Europeans View and Evaluate Democracy, ed. M. Ferrin and H.-P. Kriesi, 111–130. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Freedom House (2015) Freedom in the World. http://www.freedomhouse.org. Accessed 1 Feb 2017.

Geboers, E., F. Geijsel, W. Admiraal, and G.G. ten Dam. 2013. Review of the effects of citizenship education. Educational Research Review 9: 158–173.

Gelman, A., and J. Hill. 2006. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Held, D. 2006. Models of Democracy. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hess, R.D., and J.V. Torney. 1967. Development of Political Attitudes. Chicago: Aldine Press.

Hooghe, M., and B. Wikenfeld. 2008. The stability of political attitudes and behaviours across adolescence and early adulthood: A comparison of survey data on adolescents and young adults in eight countries. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 37 (2): 155–167.

Husveldt, V., and R. Nikolova. 2003. Students’ concepts of democracy. European Educational Review 2 (3): 396–409.

Ichilov, O. 2007. Civic knowledge of high school students in Israel: Personal and contextual determinants. Political Psychology 28 (4): 417–440.

Ichilov, O., D. Bar-Tal, and A. Mazawi. 1989. Israeli adolescents’ comprehension and evaluation of democracy. Youth and Society 21 (2): 153–169.

Inglehart, R., and C. Welzel. 2005. Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Jebril, N., V. Stetka, and M. Loveless. 2013. Media and Democratisation: What is Known about the Role of Mass Media in Transitions to Democracy. Oxford: Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism.

Jennings, M.K. 2006. Political socialization. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Behavior, ed. R.J. Dalton and H.-D. Klingemann, 29–45. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jennings, M.K., L. Stoker, and J. Bowers. 2008. Politics across generations: Family transmission re-examined. Journal of Politics 71 (3): 782–799.

Kruikemeier, S., and A. Shehata. 2017. News media use and political engagement among adolescents: An analysis of virtuous circles using panel data. Political Communication 34 (2): 221–242.

McIntosh, H., D. Hart, and J. Youniss. 2007. The influence of family political discussion on youth civic development: Which parent qualities matter? PS: Political Science & Politics 40 (3): 495–499.

McLeod, J.M. 2000. Media and civic socialization of youth. Journal of Adolescent Health 27S: 45–51.

Morlino, L. 2011. Changes for Democracy: Actors, Structures, Processes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Munck, G.L. 2016. What is democracy? A reconceptualization of the quality of democracy. Democratization 23 (1): 1–26.

Niemi, R., and J. Junn. 1998. Civic Education: What Makes Students Learn. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Nieuwelink, H., P. Dekker, F. Geijsel, and G.G. ten Dam. 2016. Democracy always comes first: Adolescents’ views on decision-making in everyday life and political democracy. Journal of Youth Studies 19 (7): 990–1006.

Pasek, J., K. Kenski, D. Romer, and K. Hall Jamieson. 2006. America’s youth and community engagement: How use of mass media is related to civic activity and political awareness in 14- to 22-year-olds. Communication Research 33 (3): 115–135.

Plutzer, E. 2002. Becoming a habitual voter: Inertia, resources, and growth in young adulthood. American Political Science Review 96 (1): 41–56.

Przeworski, A. 1999. Minimalist conception of democracy: A defense. In Democracy’s Value, ed. I. Shapiro and C. Hacker-Cordon, 23–55. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Putnam, R. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Quaranta, M. 2018. The meaning of democracy to citizens across European countries and the factors involved. Social Indicators Research 136 (3): 859–880.

Quaranta, M., and G.M. Dotti Sani. 2016. The relationship between the associational involvement of parents and children: A cross-national analysis of 18 European countries. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 45 (6): 1091–1112.

Sapiro, V. 2004. Not your parents’ political socialization: Introduction for a new generation. Annual Review of Political Science 7: 1–23.

Schedler, A., and R. Sarsfield. 2007. Democrats with adjectives: Linking direct and indirect measures of democratic support. European Journal of Political Research 46 (5): 637–659.

Schultz, W., J. Ainley, J. Fraillon, D. Kerr, and B. Losito. 2011. ICCS 2009 International Report. Amsterdam: International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement.

Shin, D.C. 2017. Popular understanding of Democracy. Oxford Research Encyclopaedia of Politics. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.80.

Sigel, R.S., and M.B. Hoskin. 1981. The Political Involvement of Adolescents. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Slater, M.D. 2007. Reinforcing spirals: The mutual influence of media selectivity and media effects and their impact on individual behavior and social identity. Communication Theory 17 (3): 281–303.

Torney-Purta, J.V. 2002. The school’s role in developing civic engagement: A study of adolescents in twenty-eight countries. Applied Developmental Science 6 (4): 203–212.

Torney-Purta, J.V. 2004. Adolescents’ political socialization in changing contexts: An international study in the spirit of Nevitt Sanford. Political Psychology 25 (3): 465–478.

Torney-Purta, J.V., R. Lehmann, H. Oswald, and W. Schultz. 2001. Citizenship and Education in Twenty-Eight Countries: Civic Knowledge and Engagement at Age Fourteen. Amsterdam: The International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement.

UNDP (2015) Human Development Reports. http://hdr.undp.org/en/data. Accessed 1 Feb 2017.

Van Deth, J.W., S. Abendschön, and M. Vollmar. 2010. Children and politics: An empirical reassessment of early political socialization. Political Psychology 32 (1): 147–174.

Verba, S., K.L. Schlozman, and H.E. Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Vollebergh, W.A.M., J. Iedema, and Q.A.W. Raaijmakers. 2001. Intergenerational transmission and the formation of cultural orientations in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family 63 (4): 1185–1198.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Quaranta, M. What makes up democracy? Meanings of democracy and their correlates among adolescents in 38 countries. Acta Polit 55, 515–537 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-019-00129-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41269-019-00129-4