Abstract

Research shows that emerging market multinational enterprises (EM-MNEs) increasingly use corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting as a global legitimation strategy. Less is known about when their CSR reporting is decoupled from their CSR performance. Drawing on neo-institutional theory, we argue that EM-MNEs’ CSR decoupling is shaped by their dual embeddedness in their home countries and the global institutional environment. We then examine how EM-MNEs’ home country institutional voids and degree of internationalization affect their tendency to engage in such decoupling. Our model receives partial support in a study of 93 MNEs from 15 emerging markets between 2005 and 2012.

Resume

La recherche montre que les entreprises multinationales des marchés émergents (EMN-ME) utilisent de plus en plus les rapports sur la responsabilité sociale des entreprises (RSE) comme stratégie de légitimation mondiale. On en sait moins sur le moment où leur rapport RSE est découplé de leur performance RSE. Sur la base de la théorie néo-institutionnelle, nous considérons que le découplage RSE des EMN-ME est façonné par leur double ancrage dans leurs pays d’origine et dans l’environnement institutionnel mondial. Nous étudions ensuite comment les vides institutionnels du pays d’origine des EMN-ME et le degré d’internationalisation affectent leur tendance à s’engager dans un tel découplage. Notre modèle est partiellement validé par une étude de 93 entreprises multinationales de 15 marchés émergents entre 2005 et 2012.

Resumen

La investigación muestra que las empresas multinacionales de mercados emergentes usan cada vez más los informes de responsabilidad social empresarial (RSE) como una estrategia de legitimación global. Poco se conoce sobre cuando los reportes de RSE están desconectados de su rendimiento de RSE. Basándonos en la teoría neo-institucional, argumentamos que la desconexión de la RSE de multinacionales de mercados emergentes está formado por su doble insertación a sus países de origen y al entorno institucional global. Entonces examinamos cómo los vacíos institucionales y el grado de internacionalización de las empresas multinacionales de mercados emergentes afecta su tendencia a embarcarse en dicha desconexión. Nuestro modelo recibe apoyo parcial en un estudio de 93 empresas multinacionales de 15 mercados emergentes entre el 2005 y el 2012.

Resumo

Pesquisas mostram que as empresas multinacionais de mercados emergentes (EM-MNEs) usam cada vez mais os relatórios de responsabilidade social corporativa (CSR) como uma estratégia de legitimação global. Pouco se sabe sobre quando o relatório de CSR é dissociado de seu desempenho em CSR. Com base na teoria neoinstitucional, argumentamos que a dissociação do CSR de EM-MNEs é moldado por sua dupla integração nos seus países de origem e no ambiente institucional global. Em seguida, examinamos como os vazios institucionais do país de origem e o grau de internacionalização das EM-MNEs afetam sua tendência de se engajar em tal dissociação. Nosso modelo recebe apoio parcial em um estudo de 93 empresas multinacionais de 15 mercados emergentes entre 2005 e 2012.

抽象

研究表明, 新兴市场跨国企业(EM-MNEs)越来越多地将企业社会责任(CSR)报告作为全球合法化战略。然而它们的CSR报告在什么时候与它们的CSR业绩脱钩所知较少。借鉴新制度理论, 我们认为, EM-MNEs的CSR脱钩是由它们在本国和全球制度环境中的双重嵌入性所造成的。我们因而研究了EM-MNEs的母国制度空隙和国际化程度如何影响它们参与这种脱钩的倾向。我们的模型在2005至2012年间对来自15个新兴市场的93家跨国企业进行的研究中获得了部分支持。

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As emerging market multinational enterprises (EM-MNEs) assume an increasing role in cross-border investment and trade (Luo & Tung, 2018), their corporate social responsibility (CSR) performance has come under scrutiny by global financial, regulatory, and societal stakeholders (UNCTAD, 2011; KPMG, 2013; Transparency International, 2016). CSR performance refers to “the principles, practices, and outcomes of businesses’ relationships with people, organizations, institutions, communities, societies, and the earth, in terms of the deliberate actions of businesses toward these stakeholders as well as the unintended externalities of business activity” (Wood, 2016: 1). To legitimize themselves with these stakeholders, EM-MNEs have turned to CSR reporting (Doh, Husted, & Yang, 2016; Fiaschi, Giuliani, & Nieri, 2016), which refers to public disclosures of a firm’s assessments of its CSR performance through various channels, including annual reports, Web sites, supplemental disclosures (e.g., 10-K), or standalone CSR reports (Fortanier, Kolk, & Pinkse, 2011). Many policymakers and multilateral and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) view CSR reporting as a global norm that helps MNEs build trust with their global stakeholders by creating transparency about their social and environmental externalities (UNCTAD, 2011). Still, CSR reporting often misrepresents or overstates the actual CSR performance of the firm, meaning that firms engage in CSR “decoupling” (Delmas & Burbano, 2011). CSR decoupling refers to a symbolic strategy whereby firms overstate their CSR performance in their disclosures to strengthen their legitimacy. While some research has explored “how, when and why” such decoupling occurs (Marquis, Toffel, & Zhou, 2016: 483), these questions are still poorly understood for EM-MNEs.

Studying these questions is warranted because EM-MNEs are now important actors in the global business arena (Luo & Tung, 2018), and it is critical that their customers, business partners, and other stakeholders around the world have realistic views of their actual behaviors and the reliability of their self-reported CSR performance. Research suggests that these firms use CSR reporting to combat the legitimation challenge of “liabilities of origin” in their global operations (Marano, Tashman, & Kostova, 2017). Liabilities of origin are a form of liabilities of foreignness, or negative stereotyping of MNEs by their global stakeholders that affects firms from emerging and developing economies (Pant & Ramachandran, 2012; Edman, 2016). Such markets are characterized by so-called institutional voids, that is, poorly functioning governance institutions that impede the effectiveness of markets (Khanna & Palepu, 1997; Doh, Rodrigues, Saka-Helmhout, & Makhija, 2017). Global stakeholders are often wary of firms from such countries because they believe that institutional voids at home constrain their capacity to act legitimately when they expand abroad (Meyer, Ding, Li, & Zhang, 2014; Marano et al., 2017). However, the same institutional voids that create liabilities of origin for EM-MNEs and necessitate more active engagement in legitimating strategies like CSR may also limit their capacity to achieve strong CSR performance. As a result, they may deploy robust CSR reporting without achieving commensurate levels of CSR performance, leading to CSR decoupling.

Our goal in this article is to explore the conditions that lead EM-MNEs to CSR decoupling, with a primary focus on the unique contextual embeddedness of such firms. We draw on neo-institutional theory and the literatures on MNE legitimacy and CSR (Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Kostova & Zaheer, 1999; Kostova, Roth, & Dacin, 2008; Bromley & Powell, 2012; Wijen, 2014) to propose two institutional drivers of CSR decoupling for EM-MNEs. First, we consider how the pervasiveness of institutional voids in EM-MNEs’ home countries drives them to engage in CSR decoupling by weakening their capacity for strong CSR performance, even though these firms face liabilities of origin that magnify the legitimacy risks of CSR decoupling. Second, we consider how EM-MNEs’ internationalization increases their exposure to global stakeholders and, by implication, institutional pressures to overcome liabilities of origin by avoiding CSR decoupling. We also consider how internationalization may attenuate the positive effect that home country institutional voids have on firms’ CSR decoupling by providing them experience in the global business arena that compensates for their limited home country experience with CSR.

Our study makes several contributions to the literatures on EM-MNEs’ country-of-origin effects, legitimacy management, and CSR (Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Marquis & Qian, 2014; Cuervo-Cazurra, Newburry, & Park, 2016; Hernandez & Guillén, 2018). Prior research has examined how home country conditions drive EM-MNEs to expand abroad to access strategic resources and markets that do not exist at home (Shi, Sun, Yan, & Zhu, 2017; Gaur, Ma, & Ding, 2018; Luo & Tung, 2007; 2018), use relationships with home country governments to compete more effective in advanced economies (Cui & Aulakh, forthcoming), and leverage country-specific advantages in other emerging markets and industries (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008; Li & Shapiro, forthcoming; Ramamurti & Hillemann, 2018). Research has also noted that EM-MNEs’ international expansion involves high barriers to legitimation in their host countries due to liabilities of origin and that they use CSR reporting to manage such challenges (Marano et al., 2017). Our study extends this research by showing that the same home country conditions that motivate EM-MNEs to internationalize and use CSR reporting to manage liabilities of origin also cause them to engage in CSR decoupling. Specifically, we show that EM-MNEs’ CSR decoupling depends on firms’ dual embeddedness at home and in the global business arena, where achieving and maintaining legitimacy is challenging. Finally, we advance research on CSR decoupling by studying factors that drive the alignment, or lack thereof, of firms’ self-disclosed and third-party-rated CSR performance. Prior work has studied CSR decoupling as the symbolic use of CSR reporting via low-quality, deceptive, or selective disclosures without examining whether such reporting was consistent with firms’ independently rated CSR performance (Marquis & Qian, 2014; Marquis et al., 2016; Luo, Wang, & Zhang, 2017).

The rest of the article is organized as follows. Next, we present the theoretical background of the study and develop our hypotheses. We then describe the research methodology and results of the study. We conclude by discussing the study’s contributions, limitations, and future research directions.

Theoretical Background and Hypotheses

We build on the international management research applying a neo-institutional lens (e.g., Westney, 1993; Zaheer, 1995; Kostova & Zaheer, 1999) and some of its more recent applications to studying emerging markets and EM-MNEs (e.g., Luo & Peng, 1999; Meyer & Peng, 2005, 2016; Marano et al., 2017). Accordingly, we view EM-MNEs as experiencing some distinctive institutional characteristics that require special examination. All MNEs operate under conditions of institutional multiplicity in transnational organizational fields with different, divergent, and possibly conflicting institutional pressures. Such conditions complicate MNEs’ efforts to establish and maintain legitimacy across their global operations (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999; Mithani, 2017). However, as a class of firms, EM-MNEs also face liabilities of origin, which are a more extreme form of liabilities of foreignness, or negative stereotyping by global stakeholders, and can translate into more serious legitimacy deficits when these firms expand abroad (Pant & Ramachandran, 2012).

Liabilities of origin occur when global stakeholders negatively stereotype EM-MNEs because of their home country’s institutional voids (Pant & Ramachandran, 2012). Due to their relative newness in the international business arena, host country stakeholders frequently lack information about EM-MNEs and develop “stereotypical judgments based on the legitimacy or illegitimacy of certain classes of organizations to which the MNE is perceived to belong. The stereotypes used to judge MNEs may arise from long-established, taken-for-granted assumptions in the host environment regarding MNEs in general, or of MNEs from a … particular home country” (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999: 74; see also Diamantopoulos, Florack, Halkias & Palcu, 2017; Gineikiene & Diamantopoulos, 2017). Because EM-MNEs are headquartered in countries with weaker institutions and lower levels of economic development, global stakeholders’ stereotypes about them include negative home country institutional attributions (Pant & Ramachandran, 2012). Cuervo-Cazurra et al. (2016: 124–125) explain how such stereotyping can stem from “general perceptions about the quality of a country’s products or issues like political instability, which can cast a negative shadow over a country and can make the purchasing of its products less desirable.” As an example, “[t]he term “Made in China” is commonly associated with low-quality products and lower technology levels … This implies a biased attitude toward Chinese companies and their products…” (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2016: 125). This attitude was evident in the Chinese automobile manufacturer Chery’s unsuccessful effort to enter the Mexican market, where local consumers revealed strong negative perceptions about the firm’s Chinese origin according to a local consulting firm’s market research on its behalf (Skolkovo, 2009; Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2016). EM-MNEs sometimes address such challenges by conforming to “recent trends in the practice of the global management of establishing guidelines and expectations for MNC behavior on a worldwide basis, primarily in the area of social responsibility” (Kostova et al., 2008: 998). Specifically, research suggests that EM-MNEs use CSR reporting to alleviate negative stakeholders’ attributions stemming from liabilities of origin by strengthening their reputation, especially among advanced economy stakeholders (Doh et al., 2016; Fiaschi et al., 2016; Marano et al., 2017). Independently, a number of studies have provided evidence that CSR-related behaviors do help firms manage their legitimacy, finding positive associations between firms’ CSR efforts and their product evaluations, customer relationship management, and treatment from regulators (e.g., Perera & Chaminda, 2013; Hong & Liskovich, 2015).

CSR Reporting, Performance, and Decoupling

Still, we have a limited understanding of whether EM-MNEs’ CSR reporting is a reliable reflection of their CSR performance, which is the ultimate objective of the practice for policymakers and multilateral organizations concerned with these firms’ commitment to CSR (UNCTAD, 2011). These actors tend to view CSR reporting as a key tool for improving CSR performance because it helps “identify strengths and weaknesses across the whole corporate responsibility spectrum” and requires “stakeholder dialogue by mapping, measuring, systematizing, and communicating what firms accomplish in the area of stakeholder-related CSR” (Vurro & Perrini, 2011: 460). Firms can then use this knowledge to upgrade their CSR capabilities and substantively address social and environmental issues across their operations.

CSR reporting also allows salient stakeholders to better evaluate firms’ CSR efforts and reward their positive externalities, or generate legitimacy pressures on them to mitigate negative ones. As the UN Conference on Trade and Development explains: “Reporting is widely viewed as the most effective tool that regulators have to encourage better corporate governance. Reporting puts information in the hands of the markets. And markets and investors make investment decisions based on this information. The markets function best when they have access to sufficient information to properly assess governance. Good information helps the markets ascertain the degree to which companies respond to shareholder needs; it reveals risks, and shows the quality of future cash flows” (UNCTAD, 2011: ix). Reporting also encourages better performance on specific issues, such as corruption. As Transparency International (2016: 6) explains: “[p]ublic reporting by companies on their anti-corruption programmes cannot be equated with actual performance, but public reporting provides an opportunity for companies to focus on their practices, and drives improvement. Good public reporting supports and promotes good behavior.”

Nonetheless, many firms engage in CSR decoupling by exaggerating their activities in these disclosures (Delmas & Burbano, 2011), or selectively disclosing “positive environmental actions while concealing negative ones to create a misleadingly positive impression of overall environmental performance” (Marquis et al., 2016: 483; see also: Lyon & Maxwell, 2011). There are several reasons for decoupling in the CSR area. While CSR reporting is becoming institutionalized among MNEs, the practice has emerged in the highly opaque field of global socioenvironmental governance, “where practices, causality, and performance are hard to understand and chart” (Wijen, 2014: 302). Specifically, the field organized around global socioenvironmental governance contains a plethora of expectations regarding CSR performance from complex social and organizational networks, which creates uncertainty for firms trying to make sense of how CSR reporting and performance are jointly evaluated (Wijen, 2014). Further, there is disparity in the effort needed to improve CSR reporting and performance. Improving CSR performance requires investments into developing novel capabilities and expertise with uncertain economic payoffs (Bansal & Kistruck, 2006). CSR reporting, on the other hand, can be modeled after other MNEs since it is a de facto global best practice (UNCTAD, 2011).

There are, however, risks and negative legitimacy implications for MNEs that exercise CSR decoupling, such as increased regulatory oversight or penalties. For example, in 2014, South Korean multinationals Kia and Hyundai were fined $300 million by the US Justice Department and Environmental Protection Agency for “overstating the gas mileage for 1.2 million vehicles” (Gelles, 2015). Similarly, in 2013 China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) and Sinopec, two leading Chinese MNCs, were banned by China’s Ministry of Environmental Protection from building new refineries or expanding existing ones because of their failure to meet emission targets and understating emission levels for four major pollutants (Stanway & Hua, 2013; Minghe, Duanduan, & Jie, 2013). Further, MNEs caught misrepresenting their CSR performance can be punished in CSR rankings and ratings (Doh, Howton, Howton, & Siegel, 2010), receive negative publicity in the media (e.g., Du, 2015), or be subject to consumer rights’ advocacy campaigns from organizations that hold firms accountable for greenwashing (e.g., the Greenwashing Index1). For example, after South Africa’s Advertising Standards Authority in 2010 (tipped by a complaint from Samsung’s competitor LG Electronics South Africa) revealed that Samsung misrepresented its eco-credentials to South African consumers, the firm faced significant negative media coverage on the heels of these investigations (Manson, 2010).

In sum, MNEs face trade-offs in coupling their CSR reporting and performance. On the one hand, the opaque field of global socioenvironmental governance makes it difficult for firms to address uncertain expectations for aligning CSR reporting and performance. On the other hand, the perception or revelation of CSR decoupling can alienate global stakeholders and undermine a firm’s legitimacy. This risk is especially high for EM-MNEs because of their inherent legitimacy deficits due to their liabilities of origin. Below we propose how pervasiveness of home country institutional voids and internationalization affect how EM-MNEs manage this trade-off.

Home Country Institutions and CSR Decoupling

As home country institutional voids become more pervasive, firms’ CSR performance may be constrained for several reasons. First, more pervasive voids imply weaker protections for labor rights, the environment, and community interests, and weaker enforcement mechanisms against socially irresponsible behavior and corruption (Campbell, 2007). Further, they lead to less robust protections for free speech and rights to organize, which help civil society generate normative pressures on firms to make substantive commitments to CSR performance (Ioannou, & Serafeim, 2012; Marquis et al., 2016). Weak institutions at home are also associated with less industry self-regulation, education, and media activity, each of which generates normative pressures for substantive CSR performance (Miska, Witt, & Stahl, 2016). Thus, more pervasive institutional voids at home broadly imply weaker institutional pressures on firms to develop the requisite capabilities to achieve adequate levels of CSR performance, as well as organizational cultures that prioritize CSR values and norms. These home country institutional effects are particularly salient prior to firms’ international expansion, when EM-MNEs are totally embedded in their home country contexts (Bansal & Kistruck, 2006). As they expand internationally, they tend to improve their CSR reporting because it is a common legitimation strategy among MNEs in the global business arena and does not require a priori changes to how firms operate their value chains (Kolk, 2010). However, aligning their CSR reporting with commensurate improvements in CSR performance may be more difficult because pervasive institutional voids at home constrain their capacity for substantive CSR behavior, which can require extensive changes to their operational capabilities (Bansal & Kistruck, 2006). Thus, more pervasive institutional voids at home should increase EM-MNEs’ CSR decoupling. More formally, we predict that:

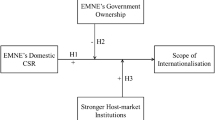

Hypothesis 1:

The pervasiveness of EM-MNEs’ home country institutional voids is positively related to CSR decoupling.

Internationalization and CSR Decoupling

As EM-MNEs internationalize and expand their presence in foreign markets, some with more stringent requirements for CSR performance, they are likely to face heightened institutional pressures to substantively improve it (Rathert, 2016). Internationalization, which refers to a firm’s reliance on exchange relationships and investments outside of its home country (Hitt, Ireland, & Hoskisson, 2007), deepens institutional embeddedness in the global business environment (Kostova et al., 2008) because “the receptivity of organizational members to a given logic is affected by the thickness of ties … linking them to the field-level institutional infrastructure” (Greenwood, Raynard, Kodeih, Micelotta, & Lounsbury, 2011: 342). Such linkages expose EM-MNEs to greater barriers to legitimation caused by liabilities of origin by increasing their dependence on host country stakeholders that are prone to negatively stereotyping these firms because of their home country conditions (Kostova & Zaheer, 1999; Pant & Ramachandran, 2012). Higher levels of internationalization also imply heightened exposure to global legitimating actors, including multilateral organizations and international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) that monitor the social and environmental impact of MNEs on a global scale (Marano & Kostova, 2016). Thus, higher levels of internationalization should increase the scrutiny by global stakeholders of EM-MNEs’ CSR efforts (Marquis et al., 2016).

Added scrutiny should dissuade EM-MNEs from engaging in CSR decoupling by increasing the likelihood that global stakeholders will uncover misrepresentations in their self-reporting. If this were to occur, global stakeholders may view these firms as intentionally deceptive about their CSR performance (Delmas & Burbano, 2011), which in turn may catalyze into long-term distrust by reinforcing pre-existing negative stereotypes associated with liabilities of origin. Since prior research has generated evidence that EM-MNEs are aware of the legitimation challenges facing them because of their home country institutions (e.g., Fiaschi et al., 2016), we expect them to be sensitive to the scrutiny that internationalization brings to their CSR disclosures and performance. As a result, higher levels of internationalization should motivate them to reduce CSR decoupling. More formally, we predict that:

Hypothesis 2:

Higher levels of EM-MNEs’ internationalization are negatively related to CSR decoupling.

Dual Embeddedness and CSR Decoupling

EM-MNEs’ dual embeddedness in home countries with institutional voids and the global business arena creates conflicting institutional expectations on these firms (Pant & Ramachandran, 2017). Thus, we expect the effects of internationalization and home country institutional voids on CSR decoupling to interact. As argued earlier, higher levels of internationalization imply more scrutiny of EM-MNEs that dissuades them from decoupling. Internationalization also exposes these firms to different knowledge and practices for addressing social and environmental issues that may not be present in their home countries (Kostova et al., 2008). Such exposure translates into new mimetic pressures to improve sensemaking around CSR issues and increases firms’ motivation and capacity to develop “creative solutions that are better suited to satisfy diverse and potentially conflicting expectations” (Marano & Kostova, 2016: 35). As Hsu and Pereira (2008: 190) explain: “The experience gained from a foreign marketplace can translate into knowledge that may be used to resolve problems or select alternative options that relate to international operations. In other words, MNEs learn when they interact with and respond to changes in their foreign markets, detect errors, and act to correct them.”

Such experiences should reduce the impact of home country institutional voids on CSR decoupling. The constraining effects of institutional voids on firms’ capacity for substantive CSR behaviors persist even after these firms expand abroad due to the institutional imprinting on organizations that “adversely impacts their ability to change their operating knowledge” (Kriauciunas & Kale, 2006: 659). However, internationalization and the resultant exposure to novel business practices and expectations may mitigate such lasting imprinting effects by introducing them to alternative cognitive models of CSR behavior (Marquis & Tilcsik, 2013). As a result, as EM-MNEs increase their degree of internationalization, the positive effects of home country institutional voids on CSR decoupling should weaken. In light of these arguments, we predict that:

Hypothesis 3:

Higher levels of EM-MNEs’ internationalization negatively moderate the relationship between home country institutional voids and CSR decoupling.

Methodology

Sample and Data

The model was tested on a sample of the largest firms in UNCTAD’s list of the top 100 non-financial EM-MNEs by foreign assets between 2005 and 2012. UNCTAD develops this list for its World Investment Report (WIR),2 a regular publication of research on global foreign direct investment (FDI) trends. This population is appropriate for our study because it encompasses emerging market firms with extensive internationalization experience in both emerging and advanced economies. Thus, they have had significant exposure to institutional pressures for CSR reporting and CSR performance. Further, they hail from 15 countries in five continents, implying that a wide range of institutional contexts are covered. Table 1 shows the distribution of the sample across countries and the descriptive statistics by country for the key variables in the model (described below in the “Variables and measures” section).

We relied on several data sources for the study. The CSR performance data were collected from the Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI) IVA (Intangible Value Assessment) database. Formerly known as Global Socrates, the IVA database measures CSR performance with ratings of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance for emerging market firms in the MSCI World Index over the timeframe of interest. CSR reporting was measured as the intensity of a firm’s CSR disclosure. We collected data for CSR reporting by content analyzing available annual financial and CSR reports, which were obtained from each firm’s Web site, the Global Reporting Initiative’s Sustainability Disclosure Database,3 and Corporate Register.4 To measure Home country institutional voids, we relied on the World Bank Governance Indicators (WGI), following several studies using these data to assess national institutional conditions (e.g., Globerman & Shapiro, 2003; Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008). We relied on the WIR for determining each firm’s home country, as well as for internationalization and financial data. Finally, additional financial data for control variables were collected from the Compustat Global (Standard and Poor’s, 2015), LexisNexis Corporate Affiliations Historical (2015), Mergent Online (2015), and Osiris (Bureau van Dijk, 2015) databases. After merging the data, our sample contained an unbalanced panel dataset of 333 firm-year observations for 93 EM-MNEs between 2005 and 2012.

Variables and Measures

Dependent variable

Since we conceptualized CSR decoupling as the degree of misalignment between a firm’s CSR reporting and CSR performance,5 we measure this variable by subtracting the standardized values of CSR performance from the standardized value of the intensity of CSR reporting.6 We standardized both of these components to ensure that they had the same measurement units, i.e., standard deviations. Thus, CSR decoupling was also measured in standard deviations. Higher scores on this measure imply that firms have high levels of CSR reporting relative to CSR performance, and thus greater degrees of misalignment between firms’ disclosure efforts and actual performance. Our approach follows the measurement method developed by Marquis et al. (2016), who measured a form of corporate environmental responsibility-related decoupling called “selective environmental disclosure magnitude” as the difference between the scope of firm’s environmental reporting and the salience of the environmental impacts that it reports. While we acknowledge the limitations that have been generally associated with aggregate CSR measures (see Waddock, 2003), our measure of CSR decoupling represents an improvement over existing measures, which have mostly relied on the quality of a firm’s CSR disclosures to capture firms’ symbolic involvement with CSR (e.g., Marquis & Qian, 2014; Luo et al., 2017).

To measure CSR performance, we rely on the industry-adjusted CSR performance scores in the IVA database developed by MSCI, which are continuous measures between 0 and 10. The IVA scores are composites of dozens of environmental, social, and governance variables measured by MSCI analysts, which fall into one of 10 themes: climate change, natural capital, pollution and waste, environmental opportunities, human capital, product liability, stakeholder opposition, social opportunities, corporate governance and corporate behavior. The factors associated with each theme are industry specific and change from time-to-time based on analysts’ assessment of the key CSR issues facing industries in each year. Thus, the composite IVA measure of a firm’s CSR performance is industry specific and is comparable across years. MSCI analysts develop these ratings using data from many sources, including corporate documents and filings, regulatory agencies, non-governmental organizations, professional associations, news media, and academic and trade journals. MSCI verifies its ratings with each company to ensure accuracy (Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI), 2014).7

We measure the intensity of CSR reporting as “the extent to which firms report on a comprehensive set of CSR issues” (Marano et al., 2017: 390–391). We adapted the approach developed by Fortanier et al. (2011), which involves coding annual and sustainability corporate reports for instances of firms’ mentioning that they recognize CSR issues that intersect with their operations and deploy practices to address those issues. Fortanier et al.’s (2011) approach to CSR reporting follows the concept of triple bottom line reporting (e.g., economic, environmental and social reporting). Because our measure of CSR decoupling uses MSCI’s CSR performance ratings of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance, we adapted Fortanier et al.’s (2011) approach to cover these same categories. Specifically, for environmental reporting, we measured five categories on the issue of climate change and efforts to reduce carbon emissions, since it is a common issue for MNEs across the globe. We measured 15 social reporting categories that capture how firms address employee, community, and broader societal issues (Fortanier et al., 2011). Finally, we measured five governance-related reporting categories covered in the IVA ratings, including issues of corruption and bribery, fair trade and competition, and corporate policies. In total, we assess firms’ reporting on 25 different dimensions of ESG performance (see Table 2).

We measure whether a firm reported on each of the 25 issues with binary items (‘0’ if the report did not report on a specific CSR issue, ‘1’ if it did). We considered a firm to have reported on an issue if it explained specific actions to address such issue and/or the external impacts of its activities related to this issue. If the issue was mentioned superficially, for example without explaining firm’s efforts to address the issue or firm’s external impacts, we did not consider the issue to be reported. This is consistent with Fortanier et al.’s (2011: 674) argument that: “In general, the mere mentioning of a particular issue (like firms would say to be ‘committed to human rights’ without any further specification) was not sufficient to be scored as reporting on a particular issue.” The initial unstandardized measure of CSR reporting was the sum of the 25 binary items. Because social issues comprised 15 of the 25 items, we divided the score of those items by three to ensure that social issues had equal weight in the measure. Thus, the final unstandardized measure of CSR reporting had a range of 0–15. To assess the reliability of the measure, one author coded each of the 333 reports and a research assistant coded a random selection of 50 reports for calculating Cohen’s kappa, which was at an acceptable level of 0.77.

Independent variables

We measured the degree of Home country institutional voids with a meta-index of the WGI. The WGI consists of six indices of a country’s institutional quality: Voice and accountability, Political stability and absence of violence, Government effectiveness, Regulatory quality, Rule of law, and Absence of corruption. The World Bank develops these indices by aggregating several hundred individual variables, drawn from 31 data sources collected by 25 organizations (Kaufmann, Kraay & Mastruzzi, 2006). Because the six WGI indices are highly correlated, we followed Globerman and Shapiro (2003) and developed a meta-index, estimated from the first principal components of the indices. We then reverse-coded the measure so higher values imply higher degrees of institutional voids (or poorer institutional quality). Following many studies in international business (e.g., Geringer, Beamish, & Costa; 1989; Tallman & Li, 1996), we measured Internationalization as the ratio of foreign sales to total sales.

Controls

We controlled for whether an EM-MNE issued a Standalone CSR report with a dummy variable (taking the value of 1 if they did). Many EM-MNEs over the timeframe of interest reported on their CSR in their annual financial disclosures; however, increasingly they are shifting to publishing standalone CSR reports (Kolk, 2010). Standalone reports may affect firms’ CSR decoupling by making their CSR activities more visible to host country stakeholders, thereby inviting scrutiny from them that may dissuade CSR decoupling (Kolk, 2010; Thorne, Mahoney & Manetti, 2014). We controlled for whether a firm was cross-listed on an Advanced economy (AE) stock exchange using a dummy variable. Such listings can create pressure on firms from advanced economy’s capital market stakeholders to conform to their CSR expectations (Marquis et al., 2016). We relied on the MSCI’s (2014) list of advanced economies to determine which exchanges are based in such countries. The advanced country exchanges in our sample are the Australian Security Exchange, Frankfurt Stock Exchange, London Stock Exchange, Luxembourg Stock Exchange, Madrid Stock Exchange, NASDAQ, National Stock Exchange of Australia, New York Stock Exchange, the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong, and the Stock Exchange of Singapore. We controlled for Profit margin since profitability can affect firms’ CSR performance by providing them with needed financial resources (McWilliams & Siegel, 2000). We controlled for Organizational slack, which can provide extra liquidity in CSR-related initiatives (Bansal, 2005). This variable was measured as the ratio of current assets to current liabilities. We controlled for Capital intensity as the ratio of assets to sales, since it can affect how firms deploy assets to improve CSR performance (Russo & Fouts, 1997). We controlled for firm Size, since larger companies tend to face greater public scrutiny and pressures over their social and environmental impacts (Christmann & Taylor, 2006). This variable was measured using the log of total revenues to reduce excessive positive kurtosis. We controlled for Research and development (R&D) intensity since innovative firms may be more able to improve their CSR performance (McWilliams & Siegel, 2000). It was measured as the ratio of R&D expenditures to sales. Due to the preponderance of missing data on firms’ research and development expenses, we followed Strike, Gao, and Bansal (2006) by using industry averages as a proxy for missing data. We then took the log of this variable to reduce excessive positive kurtosis. We controlled for state ownership with a dummy variable (State owned), since state-owned enterprise governance structures may affect their propensity to engage in CSR decoupling (Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2016). We also controlled for firms’ membership in a Business group with a dummy variable, since these firms can also have unique governance structures that affect their CSR performance (Khanna & Palepu, 1997; Marano et al., 2017). We determined firms’ affiliation with business groups from the Oxford Handbook of Business Groups (Colpan, Hikino & Lincoln, 2010), Corporate Affiliations’ corporate family tree database, and evidence from corporate reports. Finally, we include industry dummies for each firm’s two-digit Global Industry Classification Standard code, and yearly dummies to control for macro trends. Table 3 describes the variables and measures in the analyses.

Finally, we controlled for potential sample selection bias, since our sample was restricted to firms from UNCTAD’s WIR list of top 100 non-financial EM-MNEs. We followed Heckman’s (1979) selection modeling technique. Using a broader sample of firms, we estimated a first-stage model using Probit analysis where the dependent variable is membership in the main sample, predicted probabilities of membership in the main sample, and computed Inverse Mills Ratios for each observation. We then used the Inverse Mills Ratio to control for potential sample selection bias in the main analyses based on the narrower UNCTAD’s WIR sample. We relied on the Forbes Global 2000 list to draw the first-stage sample, which contains the annual ranking of the largest 2000 public companies globally by Forbes Magazine based on a mix of their sales, profits, assets, and market value (Murphy, 2015). To ensure consistency with our population of non-financial EM-MNEs, we removed observations associated with financial industries, including commercial and investment banks, investor advisory services, and real estate investment trusts. We also eliminated observations from countries that were on the United Nations’ list of advanced economies (UN, 2013). The first-stage selection model sample included all independent variables in the main analyses except for CSR reporting and listing on advanced economy stock exchange due to lack of data availability. We also included the leverage ratio (calculated as the total debt over total assets) as an exclusion restriction (Heckman, 1979). After observation attrition due to missing data, the final first-stage sample consisted of 1348 observations for 353 EM-MNEs.

Estimation Procedure

We tested our model using random effects regression with clustered robust standard errors for two reasons. First, it is a common technique for testing hypotheses on panel data with many cross sections and few time periods, and where within-panel correlations can be correlated with the error terms. Second, one of our key independent variables had limited variance over time (Home country institutional voids’ within-panel standard deviation = 0.09), and fixed effects regression is “relatively imprecise for time-varying regressors that vary little over time” (Cameron & Trivedi, 2010: 257). Prior to the analyses, we standardized each continuous variable to address non-normality issues and reduce potential for multicollinearity between the moderating and main effects (Aiken & West, 1991). We also lagged the independent variables to help establish directionality.

Results

Tables 4 and 5 present descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of the unstandardized variables, respectively. We tested for multicollinearity among the standardized variables by calculating variance inflation factors, which were well below the rule-of-thumb threshold value of 10 for all variables.

In Table 6, model 1 contains the result for the main test of Hypothesis 1, which predicted that Home country institutional voids cause EM-MNEs to engage in more CSR decoupling. The coefficient on home country institutional voids in this model is positive and significant (β = 0.19, p = 0.02; 95% confidence interval (c.i.) 0.03–0.35), suggesting that this hypothesis is supported. The coefficient indicates that a one standard deviation increase in Home country institutional voids is associated with a 0.19 standard deviation increase in CSR decoupling. Model 1 also contains the result of main test of Hypothesis 2, which predicted that Internationalization causes EM-MNEs to engage in less CSR decoupling. The coefficient on Internationalization in this model is negative and marginally significant (β = − 0.14, p = 0.06; 95% c.i. − 0.29 to 0.00) providing marginal support for this hypothesis. The coefficient indicates that a one standard deviation increase in Internationalization is associated with a 0.14 standard deviation decrease in CSR decoupling. Model 2 confirms that Home country institutional voids have a positive relationship with CSR decoupling (β = 0.19, p = 0.02; 95% c.i. 0.03–0.35) and that Internationalization has a marginally significant negative relationship with the dependent variable (β = − 0.16, p = 0.10; 95% c.i. − 0.35 to 0.03). A comparison of the range in effect sizes in the 95% confidence intervals of the coefficients on Home country institutional voids and Internationalization confirms that the former effect on CSR decoupling is more certain than the latter. Thus, our results also suggest that the effect of Home country institutional voids on CSR decoupling is more reliable than the effect of Internationalization.

Model 2 also contains the result for the main test of Hypothesis 3, which predicted that Internationalization negatively moderates the relationship between Home country institutional voids and CSR decoupling. The coefficient on Home country institutional voids * Internationalization is insignificant (β = 0.02, p = 0.75; 95% c.i. − 0.09 to 0.12), meaning the hypothesis is unsupported. Further, in each of the robustness tests in Table 7 (described below), the coefficient on this effect is insignificant, confirming that Hypothesis 3 is unsupported. This null result suggests that Internationalization does not mitigate the imprinting effects from Home country institutional voids on EM-MNEs’ CSR decoupling. We address the implications of this null result below in the Discussion section.

Robustness Tests

We conducted three robustness tests using alternative measures and methods to corroborate our results, which are reported in Table 7. First, we developed an alternative measure of the dependent variable as an ordinal measure of CSR decoupling with a range of one to six, where a score of one indicates the lowest level of CSR decoupling and a score of six indicates the highest level.8 To conduct this analysis, we used random effects ordered logistic regression with clustered robust standard errors. These results, which are reported in models 3 and 4, largely confirm the results of the main analysis.

Second, we used an alternative measure of Home country institutional voids based on the Index of Economic Freedom developed by the Fraser Institute.9 This index captures the extent to which a country’s formal and informal institutions promote economic freedom and marketplace efficiency, and is constructed primarily from data from the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the World Economic Forum, surveys, and expert opinion (Gwartney, Lawson, & Hall, 2012). We relied on this index as an alternative measure of Home country institutional voids following several other studies of institutional quality (e.g., Banalieva & Dhanaraj, 2013; El Ghoul, Guedhami, & Kim, 2017). We standardized the index to normalize it and to reduce its potential for collinearity with the interaction terms, and reverse-coded it so that higher values capture lower levels of home country institutional quality. These results, which are reported in models 5 and 6, also confirm the main results.

Finally, we conducted additional analyses controlling for CSR reporting instead of whether firms issued a Standalone CSR report (we substituted the measures because they were highly correlated). We controlled for CSR reporting because it is possible that firms that reported on a wide range of CSR issues may find it more difficult to avoid CSR decoupling in light of their comprehensive disclosures. We described how CSR reporting is a component of the main dependent variable, CSR decoupling, in the measures section. The results of these analyses, reported in models 7 and 8, also confirm the main results.

For the analyses that relied on alternative measures of independent variables, we recalculated the Inverse Mills Ratios by re-estimating the first stage of the Heckman models with those variables.

Discussion

This study was motivated by the growth in expectations among global stakeholders that EM-MNEs address the social and environmental issues associated with their global operations (Buckley, Doh, & Benischke, 2017). Prior research has shown that, as they enter global markets, EM-MNEs use CSR reporting to manage liabilities of origin with host country stakeholders (Marano et al., 2017); however, we still had limited understanding of when these efforts are genuine commitments to improving CSR performance, or exercises in CSR decoupling. To study this topic, we identified two institutional conditions that affect these firms’ propensity to engage in such decoupling: weak home country institutions that interfere with EM-MNEs’ efforts to align CSR reporting and performance; and, level of internationalization, which increases EM-MNEs’ exposure to and dependence on global stakeholders who could withhold legitimacy from these firms if they engage in CSR decoupling.

Our findings provide evidence that pervasiveness of institutional voids in EM-MNEs’ home countries drives them to engage in more CSR decoupling because such voids imply there is less institutional pressure on these firms to develop robust CSR performance prior to internationalizing. Even after they internationalize, they may find it easier to engage in symbolic CSR reporting in ways that do not correspond with their actual CSR performance, which often requires substantive changes to firms’ operational practices (Bansal & Kistruck, 2006). At the same time, our results suggest that greater levels of internationalization motivate EM-MNEs to avoid CSR decoupling and the potentially damaging consequences it can have on firms’ legitimacy.

We did not, however, find support for our interaction hypotheses of internationalization and home country institutional voids. We had argued that in EM-MNEs, internationalization increases the need for substantive CSR (due to greater legitimacy challenges abroad) and the capacity of these firms for substantive CSR (due to exposure to global CSR expectations and learning). Instead, it appears that internationalization and home country institutional voids affect CSR decoupling independently. One possible explanation is that home country institutional imprinting does not have a lasting effect after foreign expansion. Instead, the effects of institutional voids on CSR decoupling may only reflect past influences, as opposed to ongoing institutional influences that internationalization would attenuate. Another possibility is that home country imprinting on EM-MNEs regarding CSR may be particular sticky and resistant to institutional influences from foreign markets. Either way, this insignificant result suggests that country-of-origin effects on EM-MNEs’ CSR remain stable over time, even as these firms become increasingly embedded in the global arena via internationalization.

Contributions

Our study makes contributions to research on EM-MNEs’ country-of-origin effects, legitimation strategies, and CSR. First, it contributes to the research about country-of-origin and EM-MNEs’ strategies. The institutional conditions in emerging home markets act as powerful motivators for EM-MNEs to expand internationally in order to escape the economic and institutional constraints in their home countries (Luo & Tung, 2018) and exploit firm- and country-specific advantages in the global marketplace (Cuervo-Cazurra & Genc, 2008; Cui & Aulakh, forthcoming; Ramamurti & Hillemann, 2018). Such home country conditions also create liabilities of origin for EM-MNEs as they internationalize (Pant & Ramachandran, 2012). In response, EM-MNEs adopt legitimation strategies as they expand abroad, such as CSR reporting, to quell concerns about their home countries’ institutional conditions (Marano et al., 2017). Our results extend this work by showing that the same institutional voids that motivate CSR reporting also promote CSR decoupling. This suggests that these voids induce EM-MNEs to ceremonially adopt certain legitimation practices, first by pushing them to overcome country-of-origin stereotypes with such practices and then by constraining their efficacy at substantively deploying them. This may be especially true for CSR issues that have been traditionally seen as the government’s responsibility in emerging markets, such as protecting human rights. Viewing them as the prerogative of the government reduces societal expectations of corporate involvement, thus further diminishing the likelihood of EM-MNEs’ substantive initiatives in this area (Wettstein, forthcoming). The United Nations has convened several multilateral efforts to persuade emerging market governments to take a stand on corporate responsibilities for human rights, including corporate reporting. However, these efforts have only recently gained traction, mainly in the form of vague commitments that lack the institutional support to promote substantive efforts (Wettstein, 2018).

Second, our study contributes to research on EM-MNEs’ legitimation strategies (e.g., Pant & Ramachandran, 2012, 2017) by showing that EM-MNEs’ transnational institutional embeddedness, involving varying institutional conditions at home and different degrees of internationalization, affects their legitimacy management strategies (Cuervo-Cazurra & Ramamurti, 2014; Cuervo-Cazurra et al., 2016). The picture emerging from our study is one of a complex set of influences, where higher levels of internationalization seem to dissuade firms from engaging in CSR decoupling, even as more pervasive institutional voids promote it. We argued that internationalization counterbalances the effects of home country condition by increasing EM-MNEs’ exposure and dependence on global legitimating actors who are prone to negatively stereotype these firms because of their home country conditions, which increases their level of scrutiny on firms’ CSR behaviors. This scrutiny, in turn, should increase the legitimacy risks to EM-MNEs stemming from CSR decoupling and dissuade them from engaging in it. Our results also suggest that internationalization seems to provide EM-MNEs with sensemaking opportunities of the complex array of CSR expectations in the global business arena, which should help them learn how to improve actual CSR performance (Wijen, 2014).

Third, our work also addresses recent calls to study why firms engage in CSR decoupling and greenwashing (i.e., Delmas & Burbano, 2011), by conceptualizing and measuring CSR decoupling as the gap between firms’ CSR disclosures and how third parties rate their CSR performance. Several recent studies have examined decoupling as symbolic adoption of CSR reporting and have identified factors that drive its quality and materiality (e.g., Marquis & Qian, 2014; Marquis et al., 2016; Luo et al., 2017). Each of these studies, however, conceptualizes and measures decoupling as a property of CSR reporting itself, without assessing the gap between reporting and performance. Examining performance is important “in an increasingly managerial world that emphasizes evaluation, standardization, and benchmarking” (Bromley & Powell, 2012: 485), even though “scant evidence exists to show that these activities are linked to organizational effectiveness or outcomes” (Bromley & Powell, 2012: 496). Our study addresses this limitation by conceptualizing and directly measuring decoupling as the misalignment between CSR reporting and performance, to analyze whether CSR reporting is a highly rationalized “end in itself” or “a diagnostic part of a forward-looking process” (Bromley & Powell, 2012: 501).

Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations, which also serve as additional opportunities for future research. First, due to research design and data availability, our study provides a broad view of how internationalization generates institutional pressures that affects CSR decoupling. In measuring internationalization as firms’ dependence on foreign sales, we do not account for how those sales are distributed across countries with different CSR expectations, or the potential for internationalization via foreign direct investment or trade ties. Future research could use qualitative case analysis to examine a smaller set of EM-MNEs for which such data are available, in order to developed a finer-grained accounting of how global institutional embeddedness impacts CSR decoupling.

Second, we focused exclusively on EM-MNEs. Future research could analyze the drivers of CSR decoupling among different classes of firms, including advanced economy MNEs and purely domestic firms, as well as different contingencies that may be relevant to them. The degree of institutionalization of CSR reporting and performance varies across advanced economies as well as emerging ones, which translates into different pressures for firms from different countries to align reporting and actual behavior. Thus, research could further improve our understanding of CSR decoupling by studying factors that promote or discourage it among different classes of MNEs. Third, our study argues that EM-MNEs avoid CSR decoupling to manage the risks it poses to their legitimacy, but does not actually assess whether firms’ legitimacy is affected by decoupling; that is, legitimacy is employed in our article only as an underlying explanatory mechanism. Based on the literature on legitimacy of EM-MNEs, we are confident about this logic; however, future research could directly measure stakeholders’ perceptions, including the extent to which they engage in negative institutional attributions due to home country institutional voids, and modify their stereotypes based on firms’ efforts to avoid CSR decoupling. Such research would add to the limited attention that has been given to measuring implications of decoupling on organizational legitimacy (Lamin & Zaheer, 2012).

Finally, while our model interprets institutional voids as a constraint on EM-MNEs’ ability to align their CSR reporting and CSR performance, it is important to acknowledge research suggesting that firms from such countries are sometimes institutional entrepreneurs that fill institutional voids via CSR (e.g., Mair, Martí, & Ventresca, 2012). For example, EM-MNEs such as India’s Tata Group have embraced CSR efforts as a strategic priority well before many advanced economy MNEs, and developed initiatives aimed at strengthening the cultural, educational, and medical institutions of local communities in their home countries to offer better quality of life to their workers (Doh, Husted & Marano, forthcoming; Pant & Ramachandran, 2017). Since its creation in 1868, the Tata Group has pursued a philosophy of “profits with purpose” that is well captured in the following quote by its founder Jamsetji N. Tata: “In a free enterprise, the community is not just another stakeholder in business, but is in fact the very purpose of its existence” (Branzei, 2010: 3–4). The Group launched several welfare-enhancing initiatives well ahead of national legislation in India and many other western countries, including the introduction of the eight-hour working day in 1912, leave with pay in 1920, and maternity benefits in 1928 (Branzei, 2010; see also: Tata Group, 2018). Thus, future research could deploy a finer-grained qualitative approach to examine conditions that may foster certain EM-MNEs’ involvement with substantive CSR-related institution building in different locales (Greenwood et al., 2011). In addition, since the “micro” level of analysis is almost completely missing in the institutional theory-driven research about EM-MNEs, it would be interesting to examine how such impactful CSR practices become institutionalized and accepted by individuals within an EM-MNE, and the role that values and beliefs may play in this regard (Kostova & Marano, forthcoming).

Conclusion

This article provides new insights into EM-MNEs’ strategic behaviors by exploring the effects of their dual embeddedness in home countries with institutional voids, and a global business arena with higher CSR expectations and legitimacy concerns about firms from emerging markets. It extends past research that has shown how EM-MNEs tend to rely on CSR reporting as a legitimation strategy when they venture beyond their national borders. This study explores when such reporting is more likely to be decoupled from actual CSR performance. We find that home country institutional voids and internationalization of EM-MNEs shape such decoupling, through the complex mechanisms of global legitimacy pressures, lower home country expectations, limited a priori capabilities, potential learning abroad, and the reputational risks of “window dressing” with global stakeholders. One encouraging aspect of our findings is that internationalization has a positive effect on EM-MNE behaviors—it not only pushes them to represent themselves as socially responsible, but also to ensure the reliability of such representations.

Notes

-

1

The Greenwashing Index: http://greenwashingindex.com.

-

2

The World Investment Reports can be accessed from: http://unctad.org/en/Pages/Publications.aspx.

-

3

Accessed from: http://database.globalreporting.org.

-

4

Accessed from: http://corporateregister.com.

-

5

Table 3 describes the variables and measures used in the analyses. Alternative measures used to conduct robustness tests are described after the Results section.

-

6

We would like to thank one of the anonymous reviewers for suggesting this measurement approach.

-

7

Since MSCI ratings rely in part on company reports to assess firms’ CSR performance, it is important to distinguish the ratings’ use of these reports from our CSR reporting measure, since both are components of CSR decoupling. MSCI analysts use corporate reporting in conjunction with the other data sources described above to develop independent assessments of firms’ CSR performance. Thus, such data are contextualized and analyzed, and not directly incorporated into MSCI’s CSR performance ratings (MSCI, 2014). Our CSR reporting measure, on the other hand, captures the range of issues on which firms report, without attempting to determine whether such reporting corresponds to any level of CSR performance. Thus, a firm could report on its efforts to address a CSR issue and be given credit for such reporting, irrespective of whether such efforts affected its CSR performance.

-

8

We constructed this measure by coding EM-MNEs into categories depending on level of CSR decoupling. Scores of less than − 2 standard deviations were categorized as 1, scores between − 1 and − 2 standard deviations were categorized as 2, scores between − 1 and 0 standard deviations were categorized as 3, scores between 0 and 1 standard deviations were categorized as 4, scores between 1 and 2 standard deviations were categorized as 5, and scores greater than 2 standard deviations were categorized as 6.

-

9

Accessed from: https://www.fraserinstitute.org/studies/economic-freedom.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. 1991. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Banalieva, E., & Dhanaraj, C. 2013. Home-region orientation in international expansion strategies. Journal of International Business Studies, 44(2): 89–116.

Bansal, P. 2005. Evolving sustainably: A longitudinal study of corporate sustainable development. Strategic Management Journal, 26(3): 197–218.

Bansal, P., & Kistruck, G. 2006. Seeing is (not) believing: Managing the impressions of the firm’s commitment to the natural environment. Journal of Business Ethics, 67(2): 165–180.

Branzei, O. 2010. Tata: Leadership with trust. London, ON: Richard Ivey School of Business Publishing, Western University.

Bromley, P., & Powell, W. W. 2012. From smoke and mirrors to walking the talk: Decoupling in the contemporary world. Academy of Management Annals, 6(1): 483–530.

Bureau van Dijk. 2015. Osiris. Amsterdam, Netherlands.

Buckley, P. J., Doh, J. P., & Benischke, M. H. 2017. Towards a renaissance in international business research? Big questions, grand challenges, and the future of IB scholarship. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(9): 1045–1064.

Cameron, C., & Trivedi, P. 2010. Microeconometrics using Stata (2nd ed.). College Station, TX: Stata Press.

Campbell, J. 2007. Why would corporations behave in socially responsible ways? An institutional theory of corporate social responsibility. Academy of Management Review, 32(3): 946–967.

Christmann, P., & Taylor, G. 2006. Firm self-regulation through international certifiable standards: Determinants of symbolic versus substantive implementation. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6): 863–878.

Colpan, A., Hikino, T., & Lincoln, M. (Eds.). 2010. The Oxford handbook of business groups. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A., & Genc, M. 2008. Transforming disadvantages into advantages: Developing-country MNEs in the least developed countries. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(6): 957–979.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A., Newburry, W., & Park, S. H. 2016. Emerging market multinationals: Managing operational challenges for sustained international growth. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cuervo-Cazurra, A., & Ramamurti, R. 2014. Introduction. In A. Cuervo-Cazurra & R. Ramamurti (Eds.), Understanding multinationals from emerging markets (pp. 1–11). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Cui, L., & Aulakh, P. S. forthcoming. Emerging economy multinationals in advanced economies. In K. Meyer & R. Grosse (Eds.), The Oxford handbook on management in emerging markets. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Delmas, M., & Burbano, V. 2011. The drivers of greenwashing. California Management Review, 54(1): 64–87.

Diamantopoulos, A., Florack, A., Halkias, G., & Palcu, J. 2017. Explicit versus implicit country stereotypes as predictors of product preferences: Insights from the stereotype content model. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(8): 1023–1036.

Doh, J., Howton, S. D., Howton, S. W., & Siegel, D. S. 2010. Does the market respond to an endorsement of social responsibility? The role of institutions, information, and legitimacy. Journal of Management, 36(6): 1461–1485.

Doh, J., Husted, B., & Marano, V. forthcoming. Social responsibility in emerging markets. In A. McWilliams, D. Rupp, D. Siegel, G.K. Stahl & D. Waldman (Eds.), Oxford handbook of Corporate Social Responsibility: Psychological and organizational perspectives. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Doh, J., Husted, B., & Yang, X. 2016. Guest Editors’ introduction: Ethics, corporate social responsibility, and developing country multinationals. Business Ethics Quarterly, 26(3): 301–315.

Doh, J., Rodrigues, S., Saka-Helmhout, A., & Makhija, M. 2017. International business responses to institutional voids. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(3): 293–307.

Du, X. 2015. How the market values greenwashing? Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(3): 547–574.

Edman, J. 2016. Reconciling the advantages and liabilities of foreignness: Towards an identity-based framework. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(6): 674–694.

El Ghoul, S., Guedhami, O., & Kim, Y. 2017. Country-level institutions, firm value, and the role of corporate social responsibility initiatives. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(3): 360–385.

Fiaschi, D., Giuliani, E., & Nieri, F. 2016. Overcoming the liability of origin by doing no-harm: Emerging country firms’ social irresponsibility as they go global. Journal of World Business, 52(4): 546–563.

Fortanier, F., Kolk, A., & Pinkse, J. 2011. Harmonization in CSR reporting. Management International Review, 51(5): 665–696.

Gaur, A., Ma, X., & Ding, Z. 2018. Home country supportiveness/unfavorableness and outward foreign direct investment from China. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(3): 324–345.

Gelles, D. 2015. Social responsibility that rubs right off. New York: The New York Times.

Geringer, J., Beamish, P., & Costa, R. 1989. Diversification strategy and internationalization: Implications for MNE performance. Strategic Management Journal, 10(2): 109–119.

Gineikiene, J., & Diamantopoulos, A. 2017. I hate where it comes from but I still buy it: Countervailing influences of animosity and nostalgia. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(8): 992–1008.

Globerman, S., & Shapiro, D. 2003. Governance infrastructure and U.S. foreign investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 34(1): 19–39.

Greenwood, R., Raynard, M., Kodeih, F., Micelotta, E. R., & Lounsbury, M. 2011. Institutional complexity and organizational responses. Academy of Management Annals, 5(1): 317–371.

Gwartney, J., Lawson, R., & Hall, J. 2012. 2012 economic freedom dataset. Economic Freedom of the World: 2012 Annual Report. Fraser Institute. http://www.freetheworld.com/datasetsefw.html. Accessed April 2, 2014.

Heckman, J. 1979. Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1): 153–161.

Hernandez, E., & Guillén, M. 2018. What’s theoretically novel about emerging-market multinationals? Journal of International Business Studies, 49(1): 24–33.

Hitt, M. A., Ireland, R. D., & Hoskisson, R. E. 2007. Strategic management: Globalization and competitiveness. Mason, OH: Thomson South-Western.

Hong, H., & Liskovich, I. 2015. Crime, punishment and the halo effect of corporate social responsibility (No. w21215). National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Working Paper No. 21215. http://www.nber.org/papers/w21215. Accessed April 8, 2017.

Hsu, C., & Pereira, A. 2008. Internationalization and performance: The moderating effects of organizational learning. Omega, 36(2): 188–205.

Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. 2012. What drives corporate social performance? The role of nation-level institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 43(9): 834–864.

Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., & Mastruzzi, M. 2006. Governance matters V: Aggregate and individual governance indicators for 1996–2005. Policy Research Working Papers.

Khanna, T., & Palepu, K. 1997. Why focused strategies may be wrong for emerging markets. Harvard Business Review, 75(4): 41–48.

Kolk, A. 2010. Trajectories of sustainability reporting by MNCs. Journal of World Business, 45(4): 367–374.

Kostova, T., & Marano, V. forthcoming. Institutional theory perspectives on emerging economies. In K. Meyer & R. Grosse (Eds.), The Oxford handbook on management in emerging markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kostova, T., Roth, K., & Dacin, M. 2008. Institutional theory in the study of multinational corporations: A critique and new directions. Academy of Management Review, 33(4): 994–1006.

Kostova, T., & Zaheer, S. 1999. Organizational legitimacy under conditions of complexity: The case of the multinational enterprise. Academy of Management Review, 24(1): 64–81.

KPMG. 2013. The KPMG survey of corporate responsibility reporting, 2013. https://www.kpmg.com/Global/en/IssuesAndInsights/ArticlesPublications/corporate-responsibility/Documents/corporate-responsibility-reporting-survey-2013-exec-summary.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2017.

Kriauciunas, A., & Kale, P. 2006. The impact of socialist imprinting and search on resource change: A study of firms in Lithuania. Strategic Management Journal, 27(7): 659–679.

Lamin, A., & Zaheer, S. 2012. Wall Street vs. Main Street: Firm strategies for defending legitimacy and their impact on different stakeholders. Organization Science, 23(1): 47–66.

LexisNexis. 2015. Corporate affiliations online. New Providence, NJ: National Register Publishing.

Li, J., & Shapiro, D. forthcoming. Investments by emerging-economy multinationals in other emerging economies. In K. Meyer & R. Grosse (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook on management in emerging markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Luo, Y., & Peng, M. W. 1999. Learning to compete in a transition economy: Experience, environment, and performance. Journal of International Business Studies, 30(2): 269–295.

Luo, Y., & Tung, R. 2007. International expansion of emerging market enterprises: A springboard perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 38(4): 481–498.

Luo, Y., & Tung, R. 2018. A general theory of springboard MNEs. Journal of International Business Studies, 49(2): 129–152.

Luo, X. R., Wang, D., & Zhang, J. 2017. Whose call to answer: Institutional complexity and firms’ CSR reporting. Academy of Management Journal, 60(1): 321–344.

Lyon, T., & Maxwell, J. 2011. Greenwash: Corporate environmental disclosure under threat of audit. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 20(1): 3–41.

Mair, J., Martí, I., & Ventresca, M. J. 2012. Building inclusive markets in rural Bangladesh: How intermediaries work institutional voids. Academy of Management Journal, 55(4): 819–850.

Manson, H. 2010. Samsung caught greenwashing. Greenbiz.com. http://www.bizcommunity.com/Article/196/423/45934.html. Accessed April 7, 2017.

Marano, V., & Kostova, T. 2016. Unpacking the institutional complexity in adoption of CSR practices in multinational enterprises. Journal of Management Studies, 53(1): 28–54.

Marano, V., Tashman, P., & Kostova, T. 2017. Escaping the iron cage: Liabilities of origin and CSR reporting of emerging market multinational enterprises. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(3): 386–408.

Marquis, C., & Qian, C. 2014. Corporate social responsibility reporting in China: Symbol or substance? Organization Science, 25(1): 127–148.

Marquis, C., & Tilcsik, A. 2013. Imprinting: Toward a multilevel theory. Academy of Management Annals, 7(1): 195–245.

Marquis, C., Toffel, M., & Zhou, Y. 2016. Scrutiny, norms, and selective disclosure: A global study of greenwashing. Organization Science, 27(2): 483–504.

McWilliams, A., & Siegel, D. 2000. Corporate social performance and financial performance: Correlation or misspecification. Strategic Management Journal, 21(5): 603–609.

Meyer, K. E., Ding, Y., Li, J., & Zhang, H. 2014. Overcoming distrust: How state-owned enterprises adapt their foreign entries to institutional pressures abroad. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(8): 1005–1028.

Meyer, K. E., & Peng, M. W. 2005. Probing theoretically into Central and Eastern Europe: Transactions, resources, and institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 36(6): 600–621.

Meyer, K., & Peng, M. 2016. Theoretical foundations of emerging economy business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(1): 3–22.

Meyer, J., & Rowan, B. 1977. Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2): 340–363.

Minghe, L., Duanduan, Y., & Jie, F. 2013. China’s oil giants punished for environmental failings. https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/6367-China-s-oil-giants-punished-for-environmental-failings. Accessed March 31, 2017.

Miska, C., Witt, M., & Stahl, G. 2016. Drivers of global CSR integration and local CSR responsiveness: evidence from Chinese MNEs. Business Ethics Quarterly, 26(3): 317–345.

Mithani, M. 2017. Liability of foreignness, natural disasters, and corporate philanthropy. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(8): 941–963.

Morgan Stanley Capital International (MSCI). 2014. Executive summary: Intangible value assessment (IVA) methodology. https://www.msci.com/documents/10199/242721/IVA_Methodology_SUMMARY.pdf/cb947ab8-509e-44fd-8e4b-afb53771fbcb. Accessed May 15, 2017.

Murphy, A. 2015. Global 2000: Methodology. Forbes Magazine. https://www.forbes.com/sites/andreamurphy/2015/05/06/2015-global-2000-methodology/#4028b44770f9. Accessed June 11, 2017.

Online, Mergent. 2015. Mergent online. New York: Mergent.

Pant, A., & Ramachandran, J. 2012. Legitimacy beyond borders: Indian software services firms in the United States, 1984 to 2004. Global Strategy Journal, 2(3): 224–243.

Pant, A., & Ramachandran, J. 2017. Navigating identity duality in multinational subsidiaries: A paradox lens on identity claims at Hindustan Unilever 1959–2015. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(6): 664–692.

Perera, L. C. R., & Chaminda, J. W. D. 2013. Corporate social responsibility and product evaluation: The moderating role of brand familiarity. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 20(4): 245–256.

Ramamurti, R., & Hillemann, J. 2018. What is “Chinese” about Chinese multinationals? Journal of International Business Studies, 48(1): 34–48.

Rathert, N. 2016. Strategies of legitimation: MNEs and the adoption of CSR in response to host-country institutions. Journal of International Business Studies, 47(7): 858–879.

Russo, M., & Fouts, P. 1997. A resource-based perspective on corporate environmental performance and profitability. Academy of Management Journal, 40(3): 534–559.

Shi, W., Sun, S., Yan, D., & Zhu, Z. 2017. Institutional fragility and outward foreign direct investment from China. Journal of International Business Studies, 48(4): 452–476.

Skolkovo. 2009. Operational challenges facing emerging multinationals from Russia and China. SIEMS Monthly Briefing, Skolkovo Institute for Emerging Market Studies, June. https://successors.skolkovo.ru/downloads/documents/SKOLKOVO_IEMS/Research_Reports/SKOLKOVO_IEMS_Research_2009-06-10_en.pdf. Accessed March 31, 2017.

Standard and Poor’s. 2015. Compustat. Centennial, CO.

Stanway, D. & Hua, J. 2013. China environment min suspends some approvals for Sinopec, CNPC. Reuters. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-environment-oil-idUSBRE97S03G20130829. Accessed March 31, 2017.

Strike, V., Gao, J., & Bansal, P. 2006. Being good while being bad: Social responsibility and the international diversification of US firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(6): 850–862.

Tallman, S., & Li, J. 1996. Effects of international diversity and product diversity on the performance of multinational firms. Academy of Management Journal, 39(1): 179–196.

Tata Group. 2018. More than a business: A brief history of the Tata Group, its enterprises and their evolution, its leaders and value systems. http://www.tata.com/htm/heritage/HeritageOption1.html. Accessed May 31, 2018.

Thorne, L. S., Mahoney, L., & Manetti, G. 2014. Motivations for issuing standalone CSR reports: A survey of Canadian firms. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 27(4): 686–714.

Transparency International. 2016. Transparency in corporate reporting: Assessing emerging market multinationals. https://www.transparency.org/whatwedo/publication/transparency_in_corporate_reporting_assessing_emerging_market_multinat. Accessed November 1, 2017.

United Nations (UN). 2013. Composition of macro geographical (continental) regions, geographical sub-regions, and selected economic and other groupings. http://unstats.un.org/unsd/methods/m49/m49regin.htm#developed. Accessed February 1, 2015.

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). 2011. Corporate Governance Disclosure in Emerging Markets: Statistical analysis of legal requirements and company practices. http://unctad.org/en/Docs/diaeed2011d3en.pdf. Accessed May 15, 2017.

Vurro, C., & Perrini, F. 2011. Making the most of corporate social responsibility reporting: Disclosure structure and its impact on performance. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 11(4): 459–474.

Waddock, S. 2003. Myths and realities of social investing. Organization & Environment, 16(3): 369–380.

Westney, D. E. 1993. Institutionalization theory and the multinational corporation. In S. Ghoshal & D. E. Westney (Eds.), Organizational theory and the multinational corporations (pp. 53–75). New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Wettstein, F. forthcoming. Human rights, emerging economies and international business. In K. Meyer & R. Grosse (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook on management in emerging markets. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wijen, F. 2014. Means versus ends in opaque institutional fields: Trading off compliance and achievement in sustainability standard adoption. Academy of Management Review, 39(3): 302–323.