Abstract

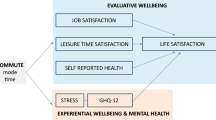

Two measures of commute time preferences – Ideal Commute Time and Relative Desired Commute amount (a variable indicating the desire to commute "much less" to "much more" than currently) – are modeled, using tobit and ordered probit, respectively. Ideal Commute Time was found to be positively related to Actual Commute Time and to a liking and utility for commuting, and negatively related to commute frequency and to a family/community-oriented lifestyle. Relative Desired Commute, on the other hand, was negatively related to amounts of actual commute and work-related travel, but positively related to travel liking and a measure of commute benefit. Overall, commute time is not unequivocally a source of disutility to be minimized, but rather offers some benefits (such as a transition between home and work). Most people have a non-zero optimum commute time, which can be violated in either direction – i.e. it is possible (although comparatively rare, occurring for only 7% of the sample) to commute too little. On the other hand, a large proportion of people (52% of the sample) are commuting longer than they would like, and hence would presumably be receptive to reducing (although usually not eliminating) that commute.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Albertson LA (1977) Telecommunications as a travel substitute: Some psychological, organizational, and social aspects. Journal of Communication27(2): 32-43.

Arnott R &; Small K (1994) The economics of traffic congestion. American Scientist82: 446-455.

Baldassare M (1991) Transportation in suburbia: Trends in attitudes, behaviors and policy preferences in Orange County, California. Transportation18: 207-222.

Cervero R (1987-88) Congestion, growth, and public choices. Berkeley Planning Journal3(2): 55-75.

Curry RW (2000) Attitudes toward Travel: The Relationships among Perceived Mobility, Travel Liking, and Relative Desired Mobility. Master's Thesis, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of California, Davis, June.

The Economist (1998) A survey of commuting: To travel hopefully. September 5, pp. 3-18.

Edmonson B (1998) In the driver's seat. American Demographics, March: 46-52.

Federal Highway Administration (1997) Our Nation's Travel: 1995 NPTS Early Results Report,US Department of Transportation, Washington DC, September.

Gordon P &; Richardson HW (1995) Sustainable congestion. In: Brotchie J, Batty M, Blakely E, Hall P, and Newton P (eds) Cities in Competition: Productive and Sustainable Cities for the 21st Century(pp 348-358). Melbourne, Australia, Longman House.

Gordon P, Richardson HW, &; Jun MJ (1991) The commuting paradox: Evidence from the top twenty. Journal of the American Planning Association57(4): 416-420.

Greene WH (1995) LIMDEP Version 7.0 User's Manual. Econometric Software, Inc, Bellport,NY.

Larson J (1998) Surviving commuting. American Demographics, July: 55ff.

Levinson DM &; Kumar A (1994) The rational locator: Why travel times have remained stable. Journal of the American Planning Association60(3): 319-332.

Lindelof B (2000) Many commuters savor private luxury of drive time. The Sacramento Bee,February 8, pp. A1 and A12.

McNamara, M (1999) On a road trip, the traffic is just part of the scenery. Los Angeles Times,November 10, p.2 of the “Living” section.

Mokhtarian PL (1998) A synthetic approach to estimating the impacts of telecommuting on travel.Urban Studies35(2): 215-241.

Mokhtarian PL &; Salomon I (1997) Modeling the desire to telecommute: The importance of attitudinal factors in behavioral models. Transportation Research A31(1): 35-50.

Mokhtarian PL &; Salomon I (forthcoming) How derived is the demand for travel? Some conceptual and measurement considerations. Transportation Research A.

Pazy A, Salomon I, &; Pintzov T (1996) The impacts of women's careers on their commuting behavior: A case study of Israeli computer professionals. Transportation Research A30(4):269–286.

Redmond LS (2000) Identifying and Analyzing Travel-related Attitudinal, Personality, and Lifestyle Clusters in the San Francisco Bay Area. Master's Thesis, Transportation Technology and Policy Graduate Group, Institute of Transportation Studies, University of California, Davis, September.

Richter J (1990) Crossing boundaries between professional and private life. In: Grossman H &; Chester L (eds) Behavioral Travel-Demand Models(pp 143-163) Hillsdale NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, Hillsdale NJ.

Salomon I &; Mokhtarian PL (1997) Coping with congestion: Understanding the gap between policy assumptions and behavior. Transportation Research D2(2): 107-123.

Salomon I &; Mokhtarian PL (1998) What happens when mobility-inclined market segments face accessibility-enhancing policies? Transportation Research D3(3): 129-140.

Shamir B (1991) Home: The perfect workplace? In: Zedeck S (ed) Work and Family(pp 273-311) San Francisco CA: Jossey-Bass.

Sipress, A (1999) Not all commuters driven crazy. Washington Post, October 18, pp. A1 and A12.

Taylor, M (2000) Drivers brave traffic tie-ups to travel solo. San Francisco Chronicle, June 19, pp. A1 and A11.

Varma K, Ho C-I, Stanek DM, &; Mokhtarian PL (1998) Duration and frequency of telecenter use: Once a telecommuter, always a telecommuter? Transportation Research C6(1&;2): 47-68.

Veall MR &; KF Zimmermann (1994) Goodness of fit measures in the tobit model. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics56(4): 485-499.

Wachs M, Taylor BD, Levine N, &; Ong P (1993) The changing commute: A case-study of the jobs-housing relationship over time. Urban Studies30(10): 1711-1729.

Young W &; Morris J (1981) Evaluation by individuals of their travel time to work. Transportation Research Record794: 51-59.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Redmond, L.S., Mokhtarian, P.L. The positive utility of the commute: modeling ideal commute time and relative desired commute amount. Transportation 28, 179–205 (2001). https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010366321778

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010366321778