Abstract

This article presents the main problems associated with cereal harvesting in sloping areas. The presented innovative aerodynamic system supporting the separating unit of combine harvester can be one of the ways to counteract the negative effects of harvesting machines work on slopes. The Monte Carlo numerical method, presented in this article, was applied in the optimization of an aerodynamic sieve separation process on an inclined terrain. The given variables are the transverse slope of separator α (of the sieve), longitudinal slope β and the output of the main and side fans. The Monte Carlo method makes it possible to determine an optimized set of parameters (α = 10°, β = 2.8°, δ = 9°), the output of the main fan (0.67 m3 s−1) and the output of the side fan (1.86 m3 s−1), allowing to obtain the best indicator values of 2.1% grain loss and 97.5% grain purity.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Growing cereal crops requires the use of combine harvesters with higher throughput capacity. Given the size limitations of a combine harvester, it is necessary to improve the elements influencing throughput capacity, i.e. for instance sieve and air flow systems [1]. From the exploitation perspective, the throughput parameter is closely connected with the level of general losses and the cleanliness of the obtained grain [2].

The pneumatic system, being one of the cleaning system elements, plays an important role in the grain cleansing process. Grain cleanliness, in turn, affects the economic effects in agriculture (reduction in costs resulting from initial seed cleaning). An appropriately used air stream results in mesh extraction: short straw, chaff, weed seeds and other light contaminations).

The process of aerodynamic sieve separation is influenced by both the kinematic and construction parameters of a sieve, as well as the aerodynamic properties of the air stream generated by a fan. During the cleaning process of a mixture on a sieve, the thickness of the layer of material is sometimes a few times thicker than the thickness of individual grains [3,4,5]. Then, an essential condition of mesh pass is mixture stratification, which, however, requires a significant increase in the kinematic indicator of a sieve and the air flow speed. The intensity of sifting is the highest at the initial section of the sieve because fine grain is sifted first as they quickly reach the bottom of a layer. According to numerous works [6, 7], the height of the distribution of cereal layers on the surface of sieve cereal is not equal.

The analysis of literature [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] showed that the currently used constructions of cleaning systems in the majority of combine harvesters are equipped with a conventional aerodynamic sieve separation system with a centrifugal fan. According to the research on combine harvesters in mountainous and foothill areas a large majority of losses and worse quality of grain result from the incorrect operation of the cleaning system.

During the operation of a combine harvester on a slope, some difficulties occur in its system functioning due to the transverse and longitudinal lean (pitch and roll) of the whole machine. The circular motion of a combine harvester in a mountainous area leads to the situation in which a machine can take four basic positions (Fig. 1: travelling uphill, on a flat area, downhill or across a slope). This results in the speed changes of grain mass on the surface of a sieve and changes in load’s mass (Fig. 2).

Source: developed based on [16]

Distribution of grain mass on the sieve surface during operation of the combine harvester in the field: a flat, b laterally inclined, c longitudinally inclined “downhill” (+ β), d) longitudinally inclined “uphill” (− β). Where: α–transverse inclination angle of the main sieve plane [º], β–longitudinal inclination angle of the main sieve plane [º].

A very important problem occurring during harvests is the fact that classical aerodynamic sieve systems used in combine harvesters operate properly on a horizontal ground, while in the case of inclinations exceeding 5º their efficiency is significantly decreased.

The exploitation of a combine harvester on inclined areas leads to disadvantageous changes related to the movements of cereal mass on the surface of sieves with respect to the direction of the resultant gravitational force. In consequence, conventional aerodynamic systems are not able to ensure sufficient mass looseness and blowing away light impurities because of the accumulation of grain, in such cases only the constant conditions of fan operation are maintained. This, among others, results in the decrease in the screening ability of the separation and cleaning system and losses of plump grain.

Due to the above, authors propose to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of grain cleansing in a combine harvester operating in varied terrain configuration by equipping the central airflow with an additional side airflow system, which would direct the airstream to the top louvered sieve. Although the solutions currently used in modern combine harvesters improve the screening ability of sieves, simultaneously they significantly increase the cost of such a machine. With regard to this economic aspect, improvements in the construction of combine harvesters must lead to the use of relatively simple and inexpensive solutions. As a rule, the price of combine harvesters grows with the efficiency of the cleaning system in a large range of slopes. Hence, research should be focused on inexpensive construction solutions for cleaning systems allowing to reduce losses during the operation of combine harvesters in the needed range of slopes in each direction.

The new constructional solution of the cleaning system requires the specification of its work parameters. Therefore, the purpose of this article is to determine optimum parameters of the screening system in combine harvester (angle of lateral incline α, the angle of longitudinal incline of terrain β, the angle set for the main fan controls δ, and the outputs of the main fan Qg and side fan Qb) in relation to two parameters: purity and losses of grain. Authors propose two approaches to the two-criterion optimization:

-

determining the acceptable level of purity of the grain (based on the previously determined regression model) and building the objective function for losses S (%) = f (α, β, δ, Qg, Qb) → min or

-

determining the acceptable level of grain losses (based on the previously determined regression model) and building the objective function for grain purity C (%) = f (α, β, δ, Qg, Qb) → max.

To achieve the goal, the task of nonlinear programming with inequality constraints was used, and the values of the parameters sought were determined using the Monte Carlo method.

2 Characteristics of the aerodynamic sieve separation process on an inclined terrain. Main problems

The aerodynamic sieve separation process in a grain combine harvester equipped with flat sieves, and working on a hilly terrain is subject to an unfavorable influence from the incline. It is particularly difficult to maintain technological parameters of equilibrium [17, 18]. As the fine grain mass begins to seep, the slope changes the component of the gravitational force with respect to the “downward” direction. The pull causes a downward movement toward the lower side of the sieve of the separator and, in some places, overloads it. On a slope exceeding 10°, the working quality of separation mechanisms (grain combines) equipped mostly with flat louvered sieves significantly deteriorates [1, 6, 19, 20].

A priority for the efficient functioning of a pneumatic sieve is ensuring that the ratio of resultant aerodynamic forces affecting grain mass to unit weight remains constant for the entire working surface of the sieve loaded with the grain mass [1], as expressed in the following equation:

In practice, the established value remains G, for which the methods of regulating the air stream involve adjusting the aerodynamic force Fw. An increase in the load carried by the sieve should be proportional to the increase in aerodynamic force Fw. The condition under which the output of the fan (or fans) ensures that the aerodynamic force Fw is equivalent to G is called the parameter of applied equilibrium [21, 22]. The greatest purity of grain in aerodynamic sieve separators is obtained by total fluidization of grain mass [23, 24]. Such conditions, considering the present construction of separators, generate losses, which should ideally amount to zero. According to Komarnicki [25], the state of applied equilibrium occurs when the aerodynamic force results in initial fluidization, characterized by bubbling on the surface of the grain mass (Fig. 3). The parameters of the air stream, in which the surface of grain shows a vertical rise of the grain mass (a visible characteristic bubbling), indicate a state of applied equilibrium between cleansing and sifting [26,27,28].

Distribution of grain mass on the working surface of a sieve for the main fan, where h = height of the grain layer and Ls = length of sieve. Source: [1]

The longitudinal positioning of grain mass on the moving bed of a sieve separator typical of a grain combine harvester is shown in Fig. 4. These results indicate a linear relationship of height h in the length function of sieve Ls. As expected, the thickness of the grain layer tends to decrease in the direction of its flow [29, 30].

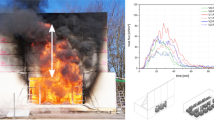

The curves shown in Fig. 5 demonstrate the variability of output Q in the phase of applied equilibrium relative to the height of the bed, and indicate an initial absence of reaction by the grain layer to the air stream. A 5-mm layer revealed localized fluidization only after reaching 1.59 m3 s−1 of output from the main fan (MF) and 1.74 m3 s−1 of output from the side fan (SF).

Variability in the applied equilibrium parameter Q versus the height of grain h. MF (main fan) and SF (side fan). Source: [1]

The preceding discussion indicates that a number of factors influence the process, the most significant of which are the output of the fan and the slope of the working platforms of the sieve [31, 32].

3 Mathematical foundations of simulation and optimization of the separation process

3.1 Description of the Monte Carlo method and formulation of the simulation problem

The Monte Carlo approach is a group of numerical methods, which can simulate physical phenomena [33,34,35,36,37,38]. A characteristic of the methods described herein is that a string of random or pseudorandom numbers is used for computation [39, 40]. Assuming that \(F\) represents the solution to a given problem (real number, string of numbers, binary decision, etc.), then applying the Monte Carlo system:

would produce the resulting value of \(F\) where \(\left\{ {r_{1} ,r_{2} , \ldots ,r_{n} } \right\}\) are random numbers. Despite using random numbers, the problem under examination need not be stochastic. A practical implementation of these simulation methods is contingent upon being able to formulate the problem in such a way that random numbers can be used to solve it [41, 42].

The Monte Carlo methods may be applied to many technical problems. If the problem in question is related to probability or stochastics, the solution would be a direct simulation. Formally speaking, all Monte Carlo calculations constitute integration. If \(F\) is the result of the Monte Carlo calculation and at the same time \(F\) is a function of random numbers \(r_{i}\), then.

Equation (3) is an unbiased estimator of a multidimensional integral

or

where integral \(I\) is the expected value of \(F\).

Let us take at random \(n\) numbers \(u_{i}\) with uniform probability within the range \(\left( {a,b} \right)\), and for every \(u_{i}\) calculate the value of function \(f\left( {u_{i} } \right)\). In accordance with the law of large numbers,

If function \(f\) is an integrated function, which is always finite and continuous (allowing for a finite number of discontinuities), then the left side of Eq. (6) is the estimator compatible with the integral on the right side. Hence, using the Monte Carlo method of computation provides the correct value if the extent of the sample becomes infinitely large.

The Monte Carlo estimator has the following properties:

-

− If variance \(V\left( f \right) < \infty\), then the estimator is compatible (i.e., convergent) with the true value of the integral for large \(n\).

-

− The estimator is unbiased for all \(n\); i.e., the expected value of the estimator is the true value of the integral.

-

− The estimator distribution is asymptotically normal.

-

− The standard deviation of the estimator may be described as

$$\sigma = \frac{1}{\sqrt n }\sqrt {V\left( f \right)} .$$(7)

If

then the Monte Carlo estimator of the integral in Eq. (8) is.

If the value of the integral in Eq. (8) is known, then the variance of estimator \(\hat{I}\) can be computed from the following equation:

In practice, variance is estimated using Eq. (9):

Therefore, the Monte Carlo estimator of standard deviation appears as:

The Monte Carlo method has its advantages and disadvantages. The advantages include:

-

− gives the opportunity to solve difficult problems;

-

− a simple form of replacing analytical solutions;

-

− the growing computing power of computers allows for more and more common use of the method;

-

− frees the user from complicated theory and formulas, allowing you to focus on the essence of the task.

The disadvantages of the Monte Carlo method include:

-

− experiments for a finite number of trials;

-

− the (simulation) results will always be an approximation;

-

− the results depend on the quality of the pseudorandom number generator.

3.2 Implementation of general simulation methods in optimization of new separation system parameters

Let the given string be \(X \subset {\mathbb{R}}^{m}\) and function F: \(X \to {\mathbb{R}}\). Let \(x = \left( {x^{1} ,x^{2} , \ldots ,x^{m} } \right) \in X\). Then, the optimization problem, in accordance with the Monte Carlo method, may be a matter of searching for a point for which.

Note that a problem formulated in this way differs from the classical search for the minimum of function \(F\) in that the search for the minimum value is limited to string \(X\), which is of primary significance in constructing algorithms [34, 35, 43,44,45,46,47,48,49].

In practice, many methods of searching for the optimal value may be used. Among the most commonly implemented ones are the “heads-and-tails method,” sequential methods, statistical optimization and genetic algorithms [35, 50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. Considering the space limitations of this paper, only the heads-and-tails method and sequential methods will be covered in detail. The computational scheme of the heads-and-tails method is presented as follows:

-

− Randomly select \(N\) points \(\left( {x_{1} ,x_{2} , \ldots ,x_{N} } \right) \in X\) in the uniform distribution system \(P\).

-

− Compute the value of function \(F\) for every point, i.e., \(F_{1} = F\left( {x_{1} } \right),F_{2} = F\left( {x_{2} } \right), \ldots ,F_{N} = F\left( {x_{N} } \right)\).

-

− Find \({{F}^{*}}=\min \left( {{F}_{1}},{{F}_{2}},\ldots ,{{F}_{N}} \right)\).

The solution to the optimization problem is

It can be observed that sequence \(\left\{ {F_{k} = F\left( {x_{k} } \right)} \right\},\,\,k = 1,2,...,N\) is one of independent variables in the same order as the cumulative distribution.

If \(F^{*} = \mathop {\min }\limits_{1 \le j \le N} F_{j}\), to \(G\left( {F^{*} } \right)\), we have

Considering that \(F^{*}\) represents positional statistics from random distribution \(\left( {F_{1} ,F_{2} ,...,F_{N} } \right)\), then

where \(g\) is the density of random variable \(F_{j}\); i.e., \(g\left( f \right) = \frac{dG\left( f \right)}{{df}}\). It can be said that with a probability \(1 - \left( {1 - \xi } \right)^{N}\), point \(x_{opt}\) was located exactly with respect to the set whose volume is less than \(\xi\). The smaller the volume of \(\xi\), the better the ability to locate point \(x_{opt}\).

A basic sequential algorithm is presented as follows:

-

− Establish the point of departure \(x_{1} \in X\) (e.g., choose from a certain probability distribution of set \(X\)).

-

− If points \(x_{1} ,x_{2} ,...,x_{n}\) have already been established, choose an auxiliary point \(\zeta_{n}\) in distribution \(P_{n}\) and calculate

$$x_{n + 1} = \left\{ \begin{gathered} x_{n} ,\quad \quad \quad dla\,\,F\left( {x_{n} + \zeta_{n} } \right) \ge F\left( {x_{n} } \right) - \varepsilon \hfill \\ x_{n} + \zeta_{n} ,\quad dla\,\,\,F\left( {x_{n} + \zeta_{n} } \right) < F\left( {x_{n} } \right) - \varepsilon \hfill \\ \end{gathered} \right.$$(18)

where \(\varepsilon\) is a positive constant. In addition, assume that \(\left\{ {\zeta_{n} } \right\}\) is an array of independent variables and that \(\left( {x_{n} + \zeta_{n} } \right) \in X\) [7].

Using the preceding algorithm, a string of points \(\left\{ {x_{n} } \right\}\) is obtained so that.

If function \(F\) is limited from the bottom, this string is convergent. If in string \(\left\{ {x_{n} } \right\}\) there appears point \(x^{\prime}\) for which \(F\left( {x_{opt} } \right) < F\left( {x^{\prime}} \right) < F\left( {x_{opt} } \right) + \varepsilon\), then in accordance with the preceding algorithm it would be repeated indefinitely; i.e., \(\mathop {\lim }\limits_{k \to \infty } x_{k} = x^{\prime}\). Note that changing the value of parameter \(\varepsilon\) makes it possible to change the value of \(x^{\prime}\).

If

then string \(\left\{ {x_{n} } \right\}\) is convergent with \(x_{opt}\) if it is convergent with any point from set \(A_{\varepsilon }\).

In our article, to optimize the separator operation parameters, we use two criteria: grain loss and grain purity. These criteria are not used separately. The optimal solution in the Pareto sense is called the x' ∈ D solution, in that there is no other solution x ∈ D that gives an improvement in the value of one or more objective functions, which do not cause deterioration of other objective functions. The optimal solution in the Pareto sense is also called efficient or effective solution. If in our case the main criterion was the grain loss (S = f ( x1, x2, x 3, x4, x 5) → min), then the secondary criterion in the form of grain purity was included in the search set as a limitation (inequality: C ≥ 92.5). In the second case, the opposite task was carried out (and we have replaced the roles of these criteria), and the solutions were verified. This is a well-known approach in the literature often referred to as the “main and secondary criterion” method. It is used when for a decision maker one criterion is basic (main) and the other is less important (secondary). The best solution is then sought for the main criterion, while ensuring a certain level of the secondary criteria implementation. Setting a compromise decision boils down to solving the task:

where \(f_{1}\)–main criterion and \(p_{k}\)–satisfactory level of implementation of the k-th secondary criterion.

So to sum up: these criteria were not considered separately, and our work is completely in line with the commonly accepted methodology.

4 Material and methods

The starting material for research was a grain mixture taken at random from a chaff riddle in a combine harvester. The mixture contained Muza wheat and natural contaminants (chaff, waste product, straw, ears, weed seeds, etc.). Before each experiment, the mass was stirred so as to obtain a structurally homogenous mixture of material cleansed in a combine harvester. Bench testing was conducted for selected combinations of setups and parameters of the cleansing system (α, β, δ, Qg, Qb).

The tests were conducted on a simulation station designed and made in the Institute of Agricultural Engineering of the Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences, a description of the station can be found in [6]. The station was modernized by the introduction of a model aerodynamic system (Fig. 6). The aerodynamic sieve system was composed of a conventional, central airflow and additional side aerodynamic systems directing the airstream to the top louvered sieve.

There were the following fans in the installation: 1–main fan being 3.05 m3 s−1 capacity and two side fans 7 and 8–2.24 m3·s−1 capacity. A change in the medium flow rate was obtained by the introduction of throttling elements in the form of multiblade dampers 3. A characteristic feature of dampers is the fact the airflow rate is decreased proportionally with its openness degree. The directed introduction of airflows under the surface of the louvered sieve was possible thanks to steering nozzles. The tests were conducted for the variable condition of fans operation:

-

angle of steering gear in nozzles δ ∈ 〈 + 9°; + 20°〉,

-

main air flow (MF) Qg ∈ 〈0,67m3s−1; 1,90m3s−1〉,

-

side air flow (SF) Qb ∈ 〈0m3s−1; 1,95m3s−1〉.

The operation quality of the aerodynamic sieve system was assessed on the basis of the grain loss indicator. A screen with a chute was mounted on the research object to collect the mass of plump wheat grain falling outside the sieve basket. In the assessment of sieve operation, grain separation losses S [%] were determined according to the following dependence:

where mzo–grain mass in waste [kg],

mw–starting material mass [kg].

After starting the operation of the tilt test station, under the influence of the airstream the cereal mass was falling into measurement containers distributed under the sieve basket. The content of the containers was weighed, and the next waste mass was separated. Grain cleanliness C was assumed to the percentage of seeds in base material per average sample of starting material, fraction or product:

where mw–average starting material mass [kg],

mz–average mass of impurities in the product [kg].

During the determination of grain cleanliness indicators, the following sieve system operation conditions were maintained:

-

sieve operating slit s = 7 mm (top sieve–wheat),

-

lateral inclination (roll rate) of the sieve basket α ∈ 〈0°; + 10°〉

-

longitudinal inclination (pitch angle) of the sieve basket β ∈ 〈− 15°; + 5°〉

-

sender of grain mass 55 kg,

-

grain supply to the sieve 3.5 kg s−1,

-

separation time t was 15 s.

4.1 Experimental verification of the proposed optimization solution: results and discussion

Monte Carlo method can be implemented to establish an optimal set of technological parameters for a separator functioning on inclined terrain. So as to achieve this, the relationship between grain purity and the output of the main fan, the output of the side fan and the angle of lateral and longitudinal incline may be approximated, with sufficient accuracy, by a second-degree polynomial as follows:

Figure 5 shows the distribution of indicators of grain mass purity C relative to the incline of terrain α, β (simulation of working across the field and uphill) and the output of the main fan Qg and side fan Qb. The effect produced by the angle of the terrain α, β to decrease the purity indicators is shown in Fig. 7a, b. Figure 7a clearly points to the negative effect of a lateral slope of sieve plane α on grain purity C. The movement of the grain mass across the sieve resulted in the deterioration of purity indicators to 92.5% with α = 10º. This condition was improved by increasing the output of the side fan Qb to 1.95 m3 s−1 at which point the maximum purity grew to 95.5%. The best result for the working quality of the aerodynamic sieve method, 97.5%, was obtained when the sieve was on a transverse plane at α = 0º and with maximum output Qb. Changing the angle of the incline of the terrain β from 5º to − 15º resulted in an increase in purity indicators to 97.9% (Fig. 7b).

The lowest grain purity of 92.6% was obtained in the simulation of the combine harvester working on a downward slope (β = 5º). It improved only when the output of the side fan Qb was increased from 0.8 to 1.95 m3 s−1; then, the maximum purity reached 97.5%. The effect of two fans functioning on the constant incline (α = 5º, β = − 5º) is shown in Fig. 7c. The highest values of purity indicators (exceeding 99%) were obtained with the maximum output of the fans at the levels of 1.9 m3 s−1 for the main fan and 1.95 m3 s−1 for the side fan.

The amount of loss is affected by the angle of lateral incline α, the angle of longitudinal incline of terrain β, the angle set for the main fan controls δ, and the outputs of the main fan Qg and side fan Qb. The matrix of coefficients of correlation between losses S and the analyzed independent factors is presented in Table 1.

The model used independent variables, which have a strong correlation with the losses and a weak correlation with each other (Table 2). Based on the results of the research tests, a mathematical model of the correlation of the amounts of loss S (%) from the previously analyzed factors was constructed. As a result of a statistical analysis, the parameters of the model for losses were estimated to be:

The formulas presented in Eqs. (24 and 25) comply with the variability:

x1 = α ∈ 〈0°; + 10°〉

x2 = β ∈ 〈− 15°; + 5°〉

x3 = δ ∈ 〈 + 9°; + 20°〉

x4 = Qg ∈ 〈0,67 m3s−1; 1,90 m3s−1.〉

x5 = Qb ∈ 〈0 m3s−1; + 1,95 m3s−1〉.

Quality optimization of the purification process involves nonlinear programming with inequality limits:

-

1.

0 ≤ x1 ≤ 10

-

2.

– 15 ≤ x2 ≤ + 5

-

3.

+ 9 ≤ x3 ≤ + 20

-

4.

0,667 ≤ x4 ≤ 1,90

-

5.

0 ≤ x5 ≤ 1,95

-

6.

\(96.46 - 0.203\alpha - 0.1\beta - 4.86Q_{b} + 0.724Q_{g}^{2} + 2.898Q_{b}^{2} \ge 92.5\)

as well as the goal function S = f (x1, x2, x3, x4, x5) → min.

An application of the Monte Carlo method determined the values of the searched parameters (α, β, δ, Qg, and Qb), which account for all the limits (with the inclusion of grain purity) and produce minimum losses. For such a problem of nonlinear optimization, the solution is a vector:

α = 10.0° (the value of the maximum lateral inclination was assumed)

β = + 2.8°

δ = 9.0° (the minimum value of the angle of main fan's blades was assumed)

Qg = 0.67 m3 s−1

Qb = 1.86 m3 s−1

C = 97.44%.

Then, losses amount to S = 2.12%.

If the angle of area inclination would change to − 5°, despite the optimization of the remaining parameters, the grain loss will exceed the admissible value (Fig. 8):

α = 10.0° (the value of the maximum lateral inclination was assumed)

β = + 5.0°

δ = 9.0° (the minimum value of the angle of main fan's blades was assumed)

Qg = 0.96 m3 s−1

Qb = 1.95 m3 s−1

C = 97.14%

S = 3.75%.

If the criterion of optimization is to maximize grain purity, we assume that the maximum losses will be:

for δ=9° (the minimum value of the angle of main fan's blades was assumed). Other restrictions are as in the above task. Goal function: C = f(x1, x2, x3, x4, x5) → max.

For such a problem of nonlinear optimization, the solution is a vector:

α = 0.0°

β = − 1.2°

δ = 9.0°

Qg = 0.667 m3 s−1

Qb = 1.95 m3 s−1

S = 2.5%.

Then, purity C = 98.45%.

The obtained result was not satisfactory for the authors. This result applies mainly to running the machine on a flat surface (α = 0°) with a slight lateral inclination (β = 1.2°). Authors in the final conclusions will remain with the results of the first optimization task (objective function: minimum grain losses, and reduce of grain purity). It is better to keep more grains even at the expense of increasing pollution–this was the premise. An increase in the output of the main fan caused an increase in purity and an increase in losses, with the losses growing intensely, as shown in Fig. 9.

The optimization of the values of purity and loss with respect to the output of the side fan (Fig. 10) demonstrated that an increase results in the improvement of the purity indicators and in the deterioration of the indicators of grain loss. The level of the purity indicators decreases from 0 to 0.7 m3 s−1, after which it starts to increase, reaching the maximum value of 96.1% (as seen in Fig. 8 which demonstrates these changes for constant values α = 10.0°; β = − 1.2°; δ = 9.0° and Qg = 0.66 m3 s−1). However, as we can see, for the maximum side fan output, the level of grain losses did not exceed the permissible 2.5% value. All optimal values of the cleaning unit operating parameters have been verified on the laboratory test station (Fig. 6) at significance level α = 0.05 (no significant differences between the predicted and obtained values).

5 Conclusions

-

1.

Multifactor regression analysis made it possible to determine mathematical models describing quantitative effects–the loss of grain S and qualitative purity C of the separation process of the grain,

S and C = f (α, β, δ, Qg, Qb),

allow for the selection of optimal fan output (Qg, Qb) for the stipulated angles of incline of field surface α, β and positioning of the steering mechanisms δ so that.

Σ C ≥ 97.5%

Σ S ≤ 2.5%.

-

2.

Applying Monte Carlo methods enabled the determination of a set of optimal technological parameters for a separator, the implementation of which should ensure normative loss indicators of 2.1% and 97.5% purity; angles of α=10.0°, β = +2.8°, and δ = 9.0°; main fan output of 0.67 m3 s−1 and side fan output of 1.86 m3 s−1.

In conclusion: on the one hand, the novelty of this article is the use of the presented modernized separation system, whose separating action on the sieve is supported by additional air streams. On the other hand, we showed in the article how we can determine the optimal parameter values in a relatively simple way and thus the best working conditions of this new separating system. The same could be achieved by solving systems of differential equations. Only what for? The Monte Carlo method allows you to "shoot" random values in a given space of variables D (a huge number of values), and this allows you to designate a counter-domain for the indicated criteria. A set of values that meets the set criteria is also a collection of optimal solutions. Is not that simpler? Through this article, we show that in this difficult task, this method can be useful with great success. This approach allows us to achieve the best operating conditions of the separation system under changing machine operating conditions (change of angles: α and β ).

Change history

20 March 2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43452-021-00213-7

References

Komarnicki P, Bieniek J, Banasiak J. Operational effectiveness of a sieve-aerodynamic separator under the conditions of variable load of sieves. Eksploatacja i Niezawodnosc – Maintenance and Reliability. 2007;4:33–5.

Lewandowski B. Research of chevron separator system for application to a combine harvester for hilly and mountainous terrain. Wrocław: Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences; 2004.

Kahrs J. Aerodynamic properties of weed seeds. Int Agrophysics. 1994;8:259–62.

Misener GC, Lee JHA. Aerodynamic separation of grain from straw and chaff in a dispersed stream. Can Agric Eng. 1973;15:62–5.

Gąsior K, Urbańska H, Grzesiek A, Zimroz R, Wyłomańska A. Identification, decomposition and segmentation of impulsive vibration signals with deterministic components–a sieving screen case study. Sensors. 2020;20:5648.

Bieniek J. Separation process of the cereal grain on the chevron sieve in change work condition. Wrocław: Wrocław University of Environmental and Life Sciences; 2003.

Detyna J. Maximum entropy as a theoretical criterion of statistical description of the granular matter separation. Wrocław: Wrocław University of Science and Technology Publishing; 2007.

Harrison HP. Grain separation and damage of an axial-flow combine. Can Agric Eng. 1992;34:49–53. https://library.csbe-scgab.ca/docs/journal/34/34_1_49_ocr.pdf

Zhao Z, Li Y, Chen J, Xu J. Grain separation loss monitoring system in combine harvester. Comput Electron Agric. 2011;76:183–8.

Schulz W, Wember T, Schwarz M. Efficient and compact development of a combine harvester cleaning system. VDI-MEG Tagung Landtechnik. 2011. p. 129–36. file://z/Ref_Works/Mahdrescher/Schulz-et-al_2011_efficient-and-compact-development-of-combine-harvester-cleaning-system.pdf

Kutzbach HD. Combine harvester cleaning systems. Landtechnik. 2001;56:392–3. file://z/Ref_Works/Mahdrescher/Kutzbach_2001_combine-harvester-cleaning-systems.pdf

Rothaug S, Böttinger S, Kutzbach HD. Combine grain cleaning unit with circular oscillation. Landtechnik. 2007;62:24–5. file://z/Ref_Works/Mahdrescher/Rothaug-et-al_2007_Reinigung-im-Mahdrescher-durch-Kreisschwinger.pdf

Mullendore DL, Windt CW, Van As H, Knoblauch M. Sieve tube geometry in relation to phloem flow. Plant Cell. 2010;22:579–93. http://www.plantcell.org/content/22/3/579.short

Craessaerts G, Saeys W, Missotten B, De Baerdemaeker J. Identification of the cleaning process on combine harvesters. Part I: A fuzzy model for prediction of the material other than grain (MOG) content in the grain bin. Biosyst Eng. 2008;101:42–9.

Krot P, Zimroz R, Michalak A, Wodecki J, Ogonowski S, Drozda M, et al. Development and verification of the diagnostic model of the sieving screen. Shock Vib. 2020;2020:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/8015465.

Banasiak J, Detyna J, Hutnik E, Szewczyk A, Zimny L. Agrotechnologia. Warszawa-Wrocław: PWN Group; 1999.

Bohorquez P, Ancey C. Particle diffusion in non-equilibrium bedload transport simulations. Appl Math Model. 2016;40:7474–92.

Krane MJM. Macrosegregation development during solidification of a multicomponent alloy with free-floating solid particles. Appl Math Model. 2004;28:95–107.

Afonso Júnior PC, Corrêa PC, Pinto FAC, Queiroz DM. Aerodynamic properties of coffee cherries and beans. Biosyst Eng. 2007;98:39–46.

Grama SN, Bern CJ, Hurburgh CR Jr. Airflow resistance of mixtures of shelled corn and fines. Trans Am Soc Agric Eng. 1984;27:268–72.

Shamloo H, Pirzadeh B. Analysis of roughness density and flow submergence effects on turbulence flow characteristics in open channels using a large eddy simulation. Appl Math Model. 2015;39:1074–86.

Zamankhan P. Solid structures in a highly agitated bed of granular materials. Appl Math Model. 2012;36:414–29.

Jayanti S, Hewitt G. Response of turbulent flow to abrupt changes in surface roughness and its relevance in horizontal annular flow. Appl Math Model. 1996;20:244–51.

Bozzi S, Passoni G. Mathematical modelling of bottom evolution by particle deposition and resuspension. Appl Math Model. 2012;36:4186–96.

Komarnicki P, Banasiak J, Bieniek J. Distribution of aerodynamic parameters of the process equilibrium state of grain cleaning. Agric Eng. 2008;4:389–96.

Bieniek J, Banasiak J, Komarnicki P. Influence of selected parameters of air stream on the separation grain mass distribution. Agric Eng. 2007;8:13–20.

Zalewski R, Chodkiewicz P, Shillor M. Vibrations of a mass-spring system using a granular-material damper. Appl Math Model. 2016;40:8033–47.

Yuan ZB, Nie YF, Liu F, Turner I, Zhang GY, Gu YT. An advanced numerical modeling for Riesz space fractional advection–dispersion equations by a meshfree approach. Appl Math Model. 2016;40:7816–29.

Verdejo H, Escudero W, Kliemann W, Awerkin A, Becker C, Vargas L. Impact of wind power generation on a large scale power system using stochastic linear stability. Appl Math Model. 2016;40:7977–87.

Lopes P, Tabor G, Carvalho RF, Leandro J. Explicit calculation of natural aeration using a Volume-of-Fluid model. Appl Math Model. 2016;40:7504–15.

Zhang T, Ouyang H, Zhang YO, Lv BL. Nonlinear dynamics of straight fluid-conveying pipes with general boundary conditions and additional springs and masses. Appl Math Model. 2016;40:7880–900.

Li D, Wang L, Wang Q, Liu G, Lu H, Zhang Q, et al. Simulations of dynamic properties of particles in horizontal rotating ellipsoidal drums. Appl Math Model. 2016;40:7708–23.

Detyna J, Bieniek J. Methods of statistical modeling in the process of sieve separation of heterogeneous particles. Appl Math Model. 2008;32:992–1002.

Li SP. A guided Monte Carlo method for optimization problems. Int J Mod Phys C. 2002;13:1365–74. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0129183102003978.

Homem-de-Mello T, Bayraksan G. Monte Carlo sampling-based methods for stochastic optimization. Surv Oper Res Manag Sci. 2014;19:56–85.

Koch KR. Monte Carlo methods. In: Freeden W. (eds) Mathematische Geodäsie/Mathematical Geodesy. Springer Reference Naturwissenschaften. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Spektrum; 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-55854-6_100

Kleywegt AJ, Shapiro A, Homem-de-Mello T. The sample average approximation method for stochastic discrete optimization. SIAM J Optim. 2002;12:479–502. https://doi.org/10.1137/S1052623499363220.

Rota G-C. Simulation and the Monte-Carlo method. Adv Math (N Y). 1986;60:123. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8708(86)90009-5.

Tadeusiewicz R, Ogiela MR. Artificial intelligence techniques in retrieval of visual data semantic information. Lect Notes Artif Intell LNAI. 2003;2663:18–27.

Hesterberg T. Monte Carlo strategies in scientific computing. Technometrics. 2002;44:403–4. https://doi.org/10.1198/tech.2002.s85.

Lu J, Dai HC. Large eddy simulation of flow and mass exchange in an embayment with or without vegetation. Appl Math Model. 2016;40:7751–67.

Kroese DP, Taimre T, Botev ZI. Handbook of Monte Carlo methods. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2011. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118014967.

McLeish D. A general method for debiasing a Monte Carlo estimator. Monte Carlo Methods Appl. 2011;17:301–15.

Giles M. Improved multilevel Monte Carlo convergence using the Milstein scheme. Monte Carlo Quasi-Monte Carlo Methods 2006. 2006;2:343–58. http://eprints.maths.ox.ac.uk/1102/

Dunn WL, Shultis JK. Exploring Monte Carlo methods. Elsevier; 2012. pp. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-51575-9.00001-4.

Dunn WL, Shultis JK. Exploring Monte Carlo methods. Elsevier; 2012. pp. 21–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-51575-9.00002-6.

Rubinstein RY, Kroese DP. Simulation and the Monte Carlo method. Second Ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2016. http://doi.wiley.com/https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470230381.

Openshaw S, Whitehead P. A Monte Carlo simulation approach to solving multicriteria optimisation problems related to planmaking, evaluation, and monitoring in local planning. Environ Plan B Plan Des. 1985;12:321–34. https://doi.org/10.1068/b120321.

Kuczma MS. Viscoelastic-plastic model for skeletal structural systems with clearances. Comput Assist Mech Eng Sci. 1999;83–106.

Iwaniec J. Output-only technique for parameter identification of nonlinear systems working under operational loads. Key Eng Mater. 2007;347:467–72.

Iwaniec J, Iwaniec M. Output-only identification of vibratory machine suspension parameters under exploitational conditions. Solid State Phenom. 2016;248:175–85.

Delgoda R, Pulfer JD. A guided Monte Carlo search algorithm for global optimization of multidimensional functions. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 1998;38:1087–95. https://doi.org/10.1021/ci9701042.

Schleder AM, Araujo PC, Martins MR. Multicriteria optimization for system configuration using Monte Carlo simulation and RAM analysis. ASME 2016 35th Int Conf Ocean Offshore Arct Eng. Busan, South Korea; 2016. https://doi.org/10.1115/OMAE2016-54274

Vrugt JA, Gupta HV, Bastidas LA, Bouten W, Sorooshian S. Effective and efficient algorithm for multiobjective optimization of hydrologic models. Water Resour Res. 2003;39:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1029/2002WR001746.

Wang W, Sebag M. Multi-objective Monte-Carlo tree search. Proc Asian Conf Mach Learn. 2012;25:507–22. http://proceedings.mlr.press/v25/wang12b/wang12b.pdf

Cios KJ, Mamitsuka H, Nagashima T, Tadeusiewicz R. Computational intelligence in solving bioinformatics problems. Artif Intell Med. 2005;35:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2005.07.001.

Kuczma MS, Świtka R. Bending of elastic beams on winkler-type viscoelastic foundations with unilateral constraints. Comput Struct. 1990;34:125–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/0045-7949(90)90306-M.

Funding

This study was funded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland, Project No. N N313 287734. The research is co-financed under the Leading Reasarch Groups support project from the subsidy increased for the period 2020–2025 in the amount of 2% of the subsidy referred to Art. 387 (3) of the Law of 20 July 2018 on Higher Education and Science, obtained in 2019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Conflict of interest

Jerzy Detyna declares that he has no conflict of interest. Jerzy Bieniek declares that he has no conflict of interest. Piotr Komarnicki declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: In the original version of this article the family name of the first author was incorrect.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bieniek, J., Komarnicki, P. & Detyna, J. Innovative aerodynamic grain separation system for plant harvesting in sloped areas: problems, research and optimization of parameters. Archiv.Civ.Mech.Eng 21, 27 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43452-021-00174-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43452-021-00174-x