Abstract

Thermal residual stresses are analyzed in SOFC components, especially in conditions when electrolyte and cathode layers are attached to other system components at different temperatures. The residual stress calculations were shown to agree with experimental data. Upon successively joining layers at different temperatures, the anode-electrolyte system has a noticeable curvature when attaching the cathode. Microcracking in individual elements of the fuel cell can be predicted through evaluation of residual stresses in anode-electrolyte (half-cell) and anode-electrolyte-cathode (full cell) systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Fuel cells transform the chemical energy of fuel directly into electrical and thermal energy; the electrochemical oxidation process is characterized by a higher efficiency and less environmental hazard than in conventional combustion conditions. High operating temperatures can lead to severe thermal degradation and hence significantly limits the choice of materials for solid oxide fuel cells (SOFC) [1, 2]. Ceramic materials are therefore predominantly used in SOFCs due to their higher corrosion resistance, but the low electrical conductivity of ceramics can limit the power output of SOFCs. Such a limitation stipulates the need for the development of SOFC with a lower operating temperature of 923–1123 K. A possible solution was the deposition of thin layers of electrolyte on the anode (cathode) substrate [3].

Despite previous earnest efforts, problems such as significant degradation of SOFC components and their intermittent operation still pose a problem. In particular, thermal cycling and oxidation result in degradation and failure of the components. These problems are the result of high temperatures and pressures required for SOFC operation, as well as inherent properties of ceramic materials [4]. Improving the mechanical behavior of fuel cell components is important to produce SOFCs with increased reliability.

Since the SOFC components are rigidly joined, the thermal expansion mismatch can lead to the appearance of residual stresses that contribute to component damage, affecting the cell's operation and efficiency [5, 6]. Stresses can arise during SOFC production (for example, in the process of sintering); this is mainly due to the difference of the thermal expansion coefficients, as well as the existence of thermal or concentration gradients [7,8,9,10]. It should be noted that during SOFC production different layers can be attached to other cell components at different temperatures. This complicates the analysis of residual stresses in such a layered structure. To the best of our knowledge there are no results published where such topic is addressed. Additional stresses can also occur in the final stages of the SOFC production, when the cells are fixed in the fuel cell stack or temperature gradients arise as the layered structures are further cooled or heated. Therefore, the study of thermal residual stresses that may contribute to SOFC component degradation is extremely relevant.

The goal of this article is to analyze the appearance of thermal residual stresses in anode-electrolyte systems (so-called half-cells) and anode-electrolyte-cathode systems (full cells), especially under conditions when electrolyte and cathode layers are attached to the system at different temperatures.

2 Experimental

2.1 Sample preparation

The composition of electrolyte used was 10 mol.% Sc2O3–1 mol.% CeO2–89 mol.% ZrO2 (10Sc1CeSZ). Anode layer consisted of mixture of 40 wt.% NiO and 60 wt.% 10Sc1CeSZ. La0.8Sr0.2Co0.8Fe0.2O3 perovskite (LSCF) was used as the cathode material. Anode material was prepared as rectangular specimens with dimensions 45 × 5.2 × 4 mm and disk-shaped samples with diameter of 22.5 mm and with thickness of 1 mm. The anode material was sintered at 1723 K. Cathode material was prepared as rectangular specimens with dimensions 45 × 5.5 × 4.5 mm. Details of fabrications of anode material are presented in [5].

The cathode material La0.8Sr0.2Co0.8Fe0.2O3 (LSCF) was prepared using the traditional solid-phase reaction with La2O3, SrO, CoO and Fe2O3 powders (purity 99%, Miranda-C). The stoichiometric compositions of the reagents were milled with ceramic balls in ethyl alcohol for 24 h. The obtained mixtures were dried and calcined in air at 1173 K for 4 h. Compact LSCF samples were obtained by uniaxial pressing of powders into bars at a pressure of 80 MPa and sintering at 1473 K for 2 h.

Electron beam deposition (EBD) technique was used for producing electrolyte films deposited on the porous, non-reduced disk-shaped anode substrates (anode-electrolyte system or half-cells). Electrolyte was deposited at 1173 K. Detailed description can be found in [5]. During full cell production, the electrolyte layer was first deposited by Electron Beam Deposition (EBD) on a flat anode at a temperature of 1173 K, and then the cathode layer was joined to the curved half-cell at a temperature of 1473 K.

2.2 Characterization

Thermal expansion analysis, four-point bending tests of rectangular specimens of SOFC materials as well as biaxial ring-on-ring bending tests of disc-shaped samples of anode substrates and half-cells are described in detail in [5]. Thermal expansion analysis were carried out with a highly sensitive quartz dilatometer having the optical system for specimen length measurement. The measurement accuracy of specimen length was 0.00025–0.0001 mm resulting from optical magnification within the range 4000–10,000. Four-point bending tests were performed using testing machine with internal and external spans 20 and 40 mm, respectively. In biaxial ring-on-ring bending tests the specimen thickness, the radii of the load ring, supporting ring and disc-shaped specimen were 1, 9, 18.6 and 23.8 mm, respectively. Five tests for anode substrates and five tests for half-cells were performed. Equibiaxial bending tests were carried out up to failure at room temperature in air. The loading rate was 1.66 N/s in all tests. The schematic for thermal expansion, four-point bending test and ring-on-ring bending test is shown in Fig. 1.

To verify the calculation of residual stresses in cells and half-cells, their curvature which arises due to the thermal expansion mismatch, was evaluated. The curvature determination includes the surface profile measurement for cells and half-cells. The profile is a set of the surface point heights over a certain horizontal plane. Further data processing includes: (a) determining the profile center; (b) rotating the profile points around its center to a position that provides a minimum standard deviation of their heights; (c) deriving the profile curvature radius by minimizing the squared deviation sum of profile points from the circle of such a radius.

3 Analysis of residual stresses

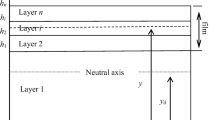

Residual stresses in a layered structure arise on a macroscopic scale. The relative layer thickness determines the relative value of residual stress. The strain mismatch between the layers determines its absolute value. Control of the thermal stresses are important to avoid damage of the layered structure during fabrication and operation. Figure 2 shows a schematic of the multilayer specimen analyzed in general case. Parameter \(w_{i}\) designates thickness of layer number i. The total thickness of specimen of rectangular cross-section is w, its width is b, the total number of layers is N (N = 2 and N = 3 for half-cell and cell, respectively). The coordinate origin is adopted to be on the free surface of first layer. When the strain depends only on x-coordinates, then the deformation compatibility condition resulting in the total strain for the elastic material should be a linear function of x [11]:

where \(\varepsilon_{0}\) is the strain at x = 0; \(k\) is the specimen curvature.

An equal biaxial stress state is the most appropriate approximation to describe stress state in the components of a planar SOFC [12]. This corresponds to smaller thickness of specimen along x-direction and large dimensions along y- and z-directions. In the equal biaxial stress state the stress components along z- and y-axis are equal. In this case the strain components along z- and y-axis are also equal. Three-dimensional stresses occur near the edges of the layered composite at a distance from the edge which is approximately equal to the thickness of the layer [13]. In our case, edge effects can be neglected due to their highly-localized character. Then.

where

In Eqs. (2) and (3) \(E(x)\) and \(\nu (x)\) are the elastic modulus and Poisson ratio distributions along x-axis, \(\tilde{\varepsilon }(x)\) is the strain non-associated with stress. It is associated with thermal expansion.

In the absence of an external load, the condition of static balance in the selected coordinate system is given by a system of linear equations with unknown values \(\varepsilon_{0}\) and \(k\) [14]:

If the external load is zero, the solution of the system is [15]:

The distribution of residual stresses can be derived from (1)–(3), (5) [16]:

\(\tilde{\varepsilon }_{i}\) is the strain in i-th layer non-associated with stress, \(x_{i}\) is the coordinate of upper boundary of i-th layer. For a layered structure, the auxiliary parameters \(I_{j}\) and \(J_{j}\) have the following form [17]:

where j is the power exponent.

The i-th layer strain which is non-associated with stress can be expressed as.

where \(\tilde{\varepsilon }_{i}^{(t)}\) is the strain associated with the thermal expansion, \(\tilde{\varepsilon }_{i}^{(g)}\) is the so-called geometric component of \(\tilde{\varepsilon }_{i}\). The strain associated with the thermal expansion is \(\tilde{\varepsilon }_{i}^{(t)} = \int\limits_{{T_{i}^{(j)} }}^{T} {\alpha_{i} (T^{\prime})dT^{\prime}}\) where \(\alpha_{i} (T)\) is the thermal expansion coefficient (TEC) of i-th layer at a temperature T; \(T_{i}^{(j)}\) is the joining temperature for layers i and i + 1. If \(\alpha_{i} (T)\) is a linear function of temperature, then \(\tilde{\varepsilon }_{i}^{(t)} = < \alpha_{i} > \Delta T_{i}\) where \(\Delta T_{i} = T - T_{i}^{(j)}\), \(< \alpha_{i} > = \frac{{\alpha_{i} (T) + \alpha_{i} (T_{i}^{(j)} )}}{2}\) is the average value of TEC in the temperature range from \(T\) to \(T_{i}^{(j)}\). The geometric component of \(\tilde{\varepsilon }_{i}\) takes into account the initial shape of the i-th layer upon its joining with (i-1)-th layer at temperature \(T_{i}^{(j)}\). This shape can be described by two parameters, namely, the strain \(\varepsilon_{0i}\) of the layered structure with i-1 layers at x = 0 and curvature \(k_{i}\) of the structure at temperature \(T_{i}^{(j)}\). Then

where \(x_{i - 1} \le x \le x_{i}\).

This approach allows the calculation of distribution of residual stresses in a layered structure, where layers are joined successively at different temperatures. The parameters \(\varepsilon_{0i}\) and \(k_{i}\) should be calculated for i ≥ 3. For i = 2, when the second layer is joined to the first layer at temperature \(T_{1}^{(j)}\), the parameters \(\varepsilon_{02}\) and \(k_{2}\) equal zero, because the first layer is flat at this joining.

4 Results and discussion

The distribution of residual stresses in the half-cell was evaluated for the conditions when EBD was performed at a temperature of 1173 K, followed by cooling to room temperature and heating to a temperature of 1473 K corresponding to the cathode sintering temperature. EBD delivers dense thin electrolyte layer [5]. The temperature of 1173 K is in fact the temperature \(T_{1}^{(j)}\) corresponding to the anode/electrolyte joining. This is stress free temperature for anode and electrolyte. Stress free temperature for anode and electrolyte joining is the temperature at which these components are bonded rigidly without plastic deformation. In fact, such rigid joining occurs during Electron Beam Deposition of electrolyte. EBD temperature is quite low to exclude any plastic deformation of components.

The initial data for calculating residual stresses in cells and half-cells are given below. The thicknesses of the anode, electrolyte and cathode layers are 990, 10, and 50 μm, respectively. The coefficient of thermal expansion for the electrolyte was adopted to be 1 × 10−5 K−1 [18]. According to experimental data, TEC values for the anode material was found to be 11.7 × 10–6 and 11.6 × 10–6 K−1 at temperatures below 1173 K and above 1173 K, respectively. TEC of LSCF cathode at temperature T was determined from the expression: [14.750158 + 0.008077 (T-273)] 10–6 K−1. The Poisson ratios of 10Sc1CeSZ electrolyte, the NiO-ScSZ anode, and the LSCF cathode are taken to be 0.31, 0.3 and 0.3, respectively [19]. The elastic moduli of the anode and the LSCF cathode determined from 4-point bending tests were 81 GPa and 14 GPa, respectively. The elastic modulus of an undamaged electrolyte was adopted to be 200 GPa [20].

The x axis is perpendicular to the anode layer and directed from anode (layer 1) to the electrolyte (layer 2) and the cathode (layer 3). The asymmetric structure of half-cell specimens results in a linear distribution of residual stresses within each layer. The values of the residual stresses in the half-cells calculated using Eq. (6) are given in Table 1. It is seen that EBD followed by cooling to room temperature leads to compressive residual stresses of about 393 MPa in the electrolyte. Accordingly, in the anode there are relatively small residual stresses (compressive stresses near the free surface, tensile stresses near the anode/electrolyte interface). At the same time, the heating of the anode-electrolyte half-cell to the cathode joining temperature results in a change in the stress sign. The tensile stress (about 126 MPa) occurs in the electrolyte layer. Increasing the temperature difference above stress free temperature for anode and electrolyte joining results in the electrolyte microcracking which promotes the significant decrease of the electrolyte elastic modulus and Poisson ratio. In turn, this leads to decreasing effective thermal stresses in the electrolyte. The experimental values of microcrack density for different temperature differences and corresponding elastic characteristics of electrolyte are given in [5].

To calculate the distribution of residual stresses in full cell, the first step is to calculate \(\varepsilon_{03}\) and \(k_{3}\) at the temperature of the cathode joining which describes the shape of the half-cell. The temperature of 1473 K is in fact temperature \(T_{2}^{(j)}\) corresponding to the electrolyte/cathode joining. This is stress free temperature for cathode. Note that the sintering of cathode layer at 1473 K accompanied by shrinkage occurs before a rigid joining is established between the cathode and electrolyte layers as solids. Thus, the shrinkage does not affect the calculation of thermal residual stresses. The characteristics of the sintered cathode material (after shrinkage) should be used for such calculation.

Schematic of successive joining layers in SOFC is presented in Fig. 3. It should be noted that microcracking occurs in the electrolyte layer of the half-cell upon heating to a temperature of 1473 K. As a result of microcracking, the elastic modulus and Poisson's coefficient of the electrolyte layer become equal to 147 GPa and 0.228, respectively. The microcracking process in the electrolyte is studied in detail in [5]. The lower elastic modulus and the Poisson ratio result in a decrease in the absolute value of the curvature of the half-cell. Then, the curvature \(k_{3}\) and strain \(\varepsilon_{03}\) of the half-cell at 1473 K equal − 0.04575 m−1 and 0.003495, respectively. The residual stresses in components of full cell can be calculated using (6)–(10). Computed stresses are presented in Table 2.

Examination of surface profiles were made to determine the curvatures of the disk-shaped anode, half-cell (anode-electrolytes) and cell (anode-electrolyte-cathode). The surface profiles of anode before electrolyte deposition (A), half-cell after electrolyte deposition before cathode joining (B) and full cell at room temperature after cathode joining (C) are shown in Fig. 4. It was found that the experimental values of the curvature at room temperature are 0.0097 ± 0.0211 m−1 (anode), 0.212 ± 0.027 m−1 (half-cell without microcracks) and − 0.215 ± 0.069 m−1 (cell with LSCF cathode), respectively. Such curvature values indicate that there are significant residual stresses in half-cells and cells, while those are practically absent in the anode. The measured curvature of a full cell clearly shows the microcracking of cathode, because the calculation indicates a much larger absolute value of the curvature of the cell in the case of cathode without microcracks (Table 2). The calculated curvatures are 0.210 for half-cell without microcracks and -0.206 for cell with LSCF cathode. Therefore, the experimental curvature values are in good agreement with the calculated ones for room temperature (Fig. 5).

Dependence of the curvature of half-cells and cells on temperature; dark and light circles indicate experimentally measured room temperature curvature of the half-cells and cells, respectively; the dashed line corresponds to the deposition temperature of the electrolyte (1173 K): 1—half-cell without microcracks; 2—half-cell with microcracks; 3—full cell with LSCF cathode

Experimental verification of thermal stress calculation for half-cells was also performed by biaxial ring-on-ring bending tests [5]. It was found that the strength of the anode samples is 41.5 ± 4.0 MPa, and that of the half-cell is 29.8 ± 3.1 MPa. The half-cells were tested in such a way that the applied tensile stress generated was in the electrolyte. In this case, the residual tensile stress in the anode near the anode/electrolyte interface is added to the applied tensile stress. Thus, the anode near the interface is the weakest link in the half-cell, and the failure of the half-cell originates in the anode. A characteristic feature of the stress–strain diagram of half-cell is the significant increase in compliance immediately before failure (Fig. 6). The onset of this increase in compliance corresponds to the beginning of anode fracture, although complete failure of the half-cell occurs after the electrolyte fracture. The anode fracture in the half-cell occured at a stress of 28.1 ± 3.0 MPa. This decrease in the anode strength (13.4 MPa on average) resulted from residual tensile stress in the anode near the anode/electrolyte interface. The corresponding calculated residual stress equals to 16 MPa, being in good agreement with the decrease in the anode strength. Therefore, the residual stress calculation is verified by experimental data.

One can see that tensile residual stresses in the electrolyte can appear when the half-cell is heated to temperatures above the temperature corresponding to the anode/electrolyte joining. A certain temperature difference and corresponding residual stresses can cause microcracking. Calculation of residual stress in SOFC components can predict critical temperature difference above which microcracking occurs in individual elements of the fuel cell. The stress of microcracking onset for 10Sc1CeSZ electrolyte is 82 MPa [5]. The critical temperature difference corresponding to this stress is found to equal to 195 K using the method described here. Microstructure of electrolyte after EBD and annealing is shown in Fig. 7. Temperature difference of 150 K (below critical difference) results in the practical absence of microcracking (Fig. 7a) while the difference of 300 K (above critical difference) leads to appearance of microcracks (Fig. 7b). Critical temperature difference predictions allow choosing technological regime to avoid microcracking in SOFC components.

5 Conclusions

-

1.

A method was proposed to evaluate thermal residual stresses in anode-electrolyte (half-cell) and anode-electrolyte-cathode (full cell) when the electrolyte layer and the cathode layer are joined successively at different temperatures. The calculations were shown to provide good agreement with experimental data.

-

2.

Heating the half-cell to temperatures above the temperature corresponding to the anode/electrolyte joining results in the appearance of tensile residual stresses in the electrolyte, which can cause microcracking to occur at a certain temperature difference.

-

3.

Upon successively joining layers at different temperatures, the cathode is attached to the anode-electrolyte system having a noticeable curvature.

-

4.

Evaluation of residual stresses in the anode-electrolyte (half-cell) and the anode-electrolyte-cathode (full cell) systems can predict microcracking in individual elements of the fuel cell resulting in loss of its efficiency or impeding its operation.

References

Wachsman ED, Lee KT (2011) Lowering the temperature of solid oxide fuel cells. Science 334:935–939

Aguadero A, Fawcett L, Taub S, Woolley R, Wu KT, Xu N, Kilner JA, Skinner SJ (2012) Materials development for intermediate-temperature solid oxide electrochemical devices. J Mater Sci 47:3925–3948

Mekhilef S, Saidur R, Safari A (2012) A comparative study of different fuel cell technologies. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 16:981–989

Mahato N, Banerjee A, Gupta A, Omar S, Balani K (2015) Progress in material selection for solid oxide fuel cell technology: a review. Prog Mater Sci 72:141–337

Lugovy M, Slyunyayev V, Steinberger-Wilckens R (2009) Microcracking in electron beam deposited scandia-stabilised zirconia electrolyte. J Power Sour 194:950–960

Shuying S, Zhengxiu F, Jianda S (2003) Evolutions of residual stress and microstructure in ZrO2 thin films deposited at different temperature and rates. Thin Solid Films 445:59–62

Armstrong TR, Stevenson JW, Pederson LR, Raney PE (1996) Dimensional instability of doped lanthanum chromite. J Electrochem Soc 143:2919–2925

Atkinson A (1997) Chemically-induced stresses in gadolinium-doped ceria solid oxide fuel cell electrolytes. Solid State Ionics 95:249–258

Recknagle KP, Williford RE, Chick LA, Rector DR, Khaleel MA (2003) Three-dimensional thermo-fluid electrochemical modeling of planar SOFC stacks. J Power Sour 113:109–114

Singh P, Minh NQ (2004) Solid oxide fuel cells: technology status. Int J Appl Ceram Technol 1:5–15

Orlovskaya N, Lugovy M, Slyunyayev V, Kuebler J (2014) Control of thermal residual stresses. In: Hetnarski RB (ed) Encyclopedia of thermal stresses. Springer, New York, pp 727–733

Radovic M, Lara-Curzio E (2004) Mechanical properties of tape cast nickel-based anode materials for solid oxide fuel cells before and after reduction in hydrogen. Acta Mater 52:5747–5756

Sergo V, Lipkin DM, de Portu G, Clarke DR (1997) Edge stresses in alumina/zirconia laminate. J Am Ceram Soc 80:1633–1638

Timoshenko SP, Goodier JN (1970) Theory of elasticity, 3rd edn. McGraw-Hill, New York

Giannakopoulos AE, Suresh S, Finot M, Olsson M (1995) Elastoplastic analysis of thermal cycling: layered materials with compositional gradients. Acta Metall Mater 43:1335–1354

Lugovy M, Slyunyayev V, Orlovskaya N, Blugan G, Kuebler J, Lewis M (2005) Apparent fracture toughness of Si3N4-based laminates with residual compressive or tensile stresses in surface layers. Acta Mater 53:289–296

Lugovy M, Slyunyayev V, Subbotin V, Orlovskaya N, Gogotsi G (2004) Crack arrest in Si3N4-based layered composites with residual stress. Compos Sci Technol 64:1947–1957

Corbin SF, Qiao X (2003) Development of solid oxide fuel cell anodes using metal-coated pore-forming agents. J Am Ceram Soc 86:401–406

Giraud S, Canel J (2008) Young’s modulus of some SOFCs materials as a function of temperature. J Eur Ceram Soc 28:77–83

Srikar VT, Turner KT, Ie TYA, Spearing SM (2004) Structural design considerations for micro-machined solid-oxide fuel cells. J Power Sour 125:62–69

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by INTAS Grant No. 06–1000024-8748 “Structure Optimization of SOFC Based on Scandia Doped Zirconia Ceramics for Space Application”. We thank Dr. J. Malzbender, Forschungszentrum Juelich, Germany, for biaxial bending tests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lugovy, M., Slyunyayev, V., Brodnikovskyy, M. et al. Residual stress distribution in solid oxide fuel cells: anode-electrolyte and anode-electrolyte-cathode systems. SN Appl. Sci. 2, 376 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-2163-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-2163-z