Abstract

The polyaniline (PANI) is an eco-friendly conductive polymer which has been considered for diverse applications. The partially oxidized phase of the PANI is useful for the charge storage application. Here, a unique nanograin/nanofiber structured PANI was grown on inexpensive stainless steel (SS) current collector by the simple oxidative polymerization process and its charge storage properties were systematically investigated. For that, the inexpensive successive ionic layer adsorption reaction method was used to grow a uniform nanostructured PANI on the SS conductor. This evolution of the nanostructure was studied with the Field emission scanning electron microscope. Furthermore, the as-prepared PANI was confirmed by the X-ray diffraction and the Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy. In the half cell electrochemical testing, the prepared PANI exhibited a maximum specific capacitance of 710 F g−1 with a specific discharge capacity of 119 mAh−1 at 0.2 mA cm−2 in 1 M H2SO4 for the supercapacitor application. Also, by using the power-law relation it was observed that, in a charging and a discharging current, initially a contribution of the diffusive faradaic reactions is more as compared with the surface capacitive non-faradaic reactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Evolution in the electrical systems for a wide spectrum of application in recent years have been increased the demand for electrical energy consumption [1, 2]. The sophisticated energy storage units with desired energy-power output for targeted electrical systems has been the main goal in front of the research community. In the global market, batteries, supercapacitors (SCs), hybrid energy storage systems have been providing the desired requirements of electrical systems. Among several energy storage systems, the Li-ion batteries are still dominating in the market for different applications, from the medical devices to the hybrid vehicles as the main central electrical energy storage and supplying system (EES) unit [3,4,5]. However, SCs with low initial capital costs, low operation-maintenance costs, with easy and efficient operation, high power density have been considered as the best option for main backup EES unit [6,7,8].

The materials generally used in the SC’s stores electrical energy either in the form of columbic (electric double layer) and faradaic (redox reaction) charge transfer process or the combination of both, which influences its power-energy output [9, 10]. The SCs having more electric double layer transitions can deliver more electric power density due to the fast charge transfer rate of adsorbed ions on the electrode surface. Whereas, the SCs having more redox transitions can deliver low power density due to poor charge transfer rate [11, 12]. More surface adsorption reaction in the charge transfer process increases the operational life cycle of SC, which generates the poor output energy. However, volume expansion and phase transition during the redox reaction leads to a decrease in the operational lifecycle of SCs [13]. This has been encouraging to study the different choices of materials to minimize these possible drawbacks for the efficient SC power-energy output.

PANI is low cost, chemically stable and good electrical conductive polymer with tunable electrochemical properties. Due to its environmental friendly nature, it is used in several applications such as gas sensor [14], anticorrosive coatings [15], OLED [16], conductive adhesive, antistatic textile, electro-rheological (ER), capacitor, solar cell, electromagnetic shield interference [17]. The electrical energy storage property of PANI involves the fast redox reaction due to doping and de-doping of cation from the electrolyte, which makes it a promising candidate for the SC application. Here, the degree of protonation decides the conductivity of PANI. Fully oxidized state or reduced state of the PANI may not be electron-conducting but half oxidized state is conductive [13].

The PANI has been synthesized using chemical oxidative polymerization, chemical bath deposition, non-emulsion, electrochemical, interfacial polymerization method [18,19,20,21,22,23]. These methods have serious drawbacks such as the polymerization of aniline monomer which generates unnecessary precipitations causing wastage of material. Also, in the electro-polymerization the desired electrochemical setup is necessary. On the other side, a simple, inexpensive successive ionic layer adsorption reaction (SILAR) method has been used for the synthesis of PANI to overcome these drawbacks [24,25,26]. Also, using the SILAR method it can be possible to synthesize a large area thin films with uniform surface morphology in which thickness and composition can be easily controlled by easy preparative parameters such as a number of cycles and process of immersion [27, 28]. Previously PANI thin films have been synthesized using SILAR method, Kulkarni et al. [26] prepared a fused nanorods on stainless steel and glass substrate, Parez et al. [29] prepared a fiber like porous structure on Whatman filter paper. Arejola et al. [30] prepared on polyethylene board, Patil et al. [31] used different surfactants to prepare different nanostructures on SS substrate, Chougale et al. [32] prepared interconnected nano-fibrous structure on a glass substrate. However, more studies related to the capacitive properties of PANI prepared by SILAR method are needed which is imperative for the SC application. The inexpensive, simple preparation method for PANI and the study of its electrochemical properties may provide a very good insight of its possible application.

In this study, the PANI films were synthesized on SS substrate by SILAR method. A number of SILAR cycles was optimized to get the films thickness of PANI on SS substrate. The filed emmision scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM) analysis was performed in order to understand the development of nanostructure on the substrate. The optimized PANI film was subjected to X-ray diffraction (XRD) and fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy studies for further confirmation. Finally, the electrochemical properties of PANI films were tested by the three electrode measurement setup in order to understand the capacitive origin and to measure the specific capacitance for the SC application.

2 Experimental

2.1 Chemicals and materials

All chemicals used for the synthesis were analytical grade. Aniline monomer, H2SO4, ammonium persulphate ((NH)4)2S2O8, were purchased from S.D. fine chemicals, India. All the solutions were prepared in double distilled water.

2.2 Synthesis of PANI films

The SS substrate was used as a current collector base for deposition of a PANI thin film. Before deposition, the SS substrates were mirror polished, then etched in 10% H2SO4 for 2 min and subjected to ultrasonication in order to remove surface contamination [33]. As shown in Fig. 1, the four solution baths were prepared for a SILAR setup. A chemical bath A is filled with 0.5 M aniline monomer + 1 M H2SO4, a chemical bath C contains 1 M ammonium persulphate, Bath B and D are filled with double distilled water.

In the typical procedure of single SILAR cycle, the pretreated SS substrate was dipped in the chemical bath A for 10 s for adsorption of an aniline monomer on its surface. Then, this substrate was taken out and rinsed in double distilled bath B for 5 s to remove loosely bound adsorbed aniline monomer. Furthermore, the substrate with the adsorbed aniline monomer was taken out from bath B and dipped into the chemical bath C for 15 s. In this step, the oxidation of adsorbed aniline monomer takes place due to the presence of an ammonium persulphate to form a thin layer of PANI on to the substrate surface. Then, the substrate coated with the PANI thin film was taken out from the bath C and rinsed in the double distilled bath D for 5 s to remove loosely bound species. The nanostructured PANI were prepared by repeating 20, 25, 30 and 35 SILAR cycles designated as P-1, P-2, P-3 and P-4 respectively.

2.3 Preparation of electrode for electrochemical testing

The electrochemical testing of the PANI thin films was performed in 1 M H2SO4. In typical three-electrode setup, the prepared PANI thin films on SS were directly used as a working electrode, the saturated calomel electrode (SCE) was used as a reference electrode and the platinum was used as a counter electrode. The electrochemical testing was carried out by cyclic voltammetry (CV), galvanostatic charge–discharge (GCD) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) studies. The specific capacitance is measured from CV and nonlinear GCD curves using following relation [34, 35].

where C is capacitance, \(\int IdV\) is area under CV curve in CV s−1, v is the scan rate in V s−1, ΔV is potential window in V, I is the constant discharge current in A, \(\int V\Delta t\) is the area under the discharge curve, IRdrop is the IR voltage drop of the galvanostatic discharge curve in V. The CS is the specific capacitance in F g−1 and m is the mass of active material on to the current collector in g. The specific capacitance is voltage-dependent parameter however for non-linear GCD curves charge storage is also expressed in terms of specific discharge capacity which is independent of working potential, given by following relation [36].

where Qd is the specific discharge capacity in mAh g−1, td is the discharge time in s.

3 Result and discussion

In single SILAR cycle, ammonium persulphate oxidizes aniline monomer to form a PANI hydrogen sulfate. A reaction mechanism regarding the formation of PANI could be shown in Fig. 2 [37, 38]. The thickness of prepared thin film was measured in terms of deposited mass by gravimetric weight difference method. The mass of P-1, P-2, P-3 and P-4 is estimated as 0.23, 0.41, 0.66 and 0.51 mg cm−2 respectively. It is observed that, the deposited mass increased from 20 to 30 cycles and gets decreased from 30 to 35 cycles due to the overgrowth and subsequent collapsing of the film [39,40,41,42]. Meticulous monitoring of the film thickness is important because an increase in the film thickness increases mass loading on the substrate which reduces the stress to the substrate, results in peeling off the overgrown mass [42]. The maximum mass is observed for P-3 which was further evaluated by XRD and FT-IR studies.

The structural evolution of PANI can be understood by the FE-SEM study. Different magnification FE-SEM images of P-1, P-2, P-3 and P-4 are shown in Fig. 3. Each SILAR cycle introduce more PANI to the film by polymerization process. After 20 SILAR cycles, the small grains of PANI are formed on the substrate surface as shown in Fig. 3a, b. With 25 SILAR cycles, the grain structure converted into the clusters of PANI as shown in Fig. 3c which are highlighted by circles. The high magnification image of these highlighted regions clearly evident that the clusters are composed of a unique mixed nanograins/nanofibers structure as shown in Fig. 3d. After 30 SILAR cycles, the three-dimension growth of clusters formed a porous network of mixed nanograins/nanofiber structure of PANI as shown in Fig. 3e, which are highlighted by circles. The magnified image of these pores reveals the formation of a porous-compact structure composed of the nanograins/nanofibers of PANI as shown in Fig. 3f. The depletion of porosity in the compact structure is observed for 35 SILAR cycles as shown in Fig. 3g, h due to overgrowth by more addition of PANI which is consistent with the gravimetric mass measurement. Several studies reported the similar growth mechanism by oxidative polymerization reaction [43,44,45]. The approximate diameter of PANI nanofiber is found in the range of 100–125 nm. This porous mixed nanograins/nanofiber structured PANI is very useful for electrolyte ion intercalation process [10, 46].

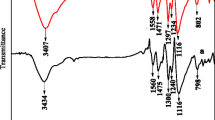

The X-ray diffraction of P-3 was performed at an angle 2θ from 20° to 80° as shown in Fig. 4a. Several reflecting planes are observed in the region of 20° to 35° indicating the presence of some degree of crystallinity in P-3. The broad peak centered around 25.2° and 28.1°, exhibits the amorphous nature of P-3. The prominent characteristics peaks observed at 2θ values of 20.8°, 25.2°, 28.1°, 29.0° and 33.3° are associated with JCPDS card no. 53-1717. In addition to that, a peak around 22.5° (not highlighted in Fig. 4a) is associated with the (021) lattice plane of JCPDS card no. 53-1891, both are associated with the orthorhombic crystal structure [47,48,49,50,51,52].This small degree of crystallinity is ascribed to the periodicity of benzenoid and quinoid rings present in the PANI structure [53, 54]. Furthermore, P-3 was subjected to the FT-IR analysis as shown in Fig. 4b revealing several IR absorption peaks present in the sample. The protonation of PANI induces the stretching modes in NH2+, represented by 3434 cm−1 [55]. The peak present at 2923 cm−1 is associated with N–H mode [55]. The peaks present at 1573 cm−1 and 1492 cm−1 are attributed to the well-known C–C stretching vibration mode of the quinoid ring and benzenoid ring [56, 57]. The stretching vibration of C–N with the aromatic ring is represented by 1305 cm−1 [55, 58]. The peaks at 1109, 810, 616 and 504 cm−1 are associated with the bending vibrations of C–H bonds in the aromatic rings [55, 56].

All PANI thin films prepared at different SILAR cycles were subjected to CV at a potential window from − 0.2 to 0.8 V (vs. SCE) at a constant scan rate of 50 mV s−1 as shown in Fig. 5a. All CV curves show a broad oxidation and reduction peak ascribed to the pseudocapacitive behavior of PANI. These broad peaks are associated with the conversion of leucomeraldine to emeraldine and emeraldine to pernigraniline forms of PANI [59,60,61]. It is observed that the area under CV curves increased from P-1 to P-3 and it is maximum for P-3. Here, the increased mass from P-1 to P-3 effectively increased the utilizing surface of PANI nanostructure which may increase the number of transitions including redox transitions due to the diffusion of ions along with surface capacitive transitions due to the electric double layer. This is consistent with the FE-SEM study which showed that the porosity of PANI is increased from P-1 to P-3. However, P-4 has a low area under the CV curve than P-4 ascribed to decreased mass and depleted porosity which effectively decreased utilizing surface [62].

a The cyclic voltammetry curves of P-1, P-2, P-3 and P-4 electrodes at 50 mVs−1 scan rates, b The plot of calculated specific capacitance of PANI electrodes from CV curves at 50 mV s−1 scan rates, c The cyclic voltammetry curves of P-3 electrodes at different scan rates from 5 to 100 mVs−1, d Variation of b-values with cathodic and anodic potential scan. Inset shows (i) Power law dependence of current on scan rate at − 0.1 V[cathodic] and 0.7 V[anodic], (ii) The capacitive distribution of total current on voltammetric response at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1

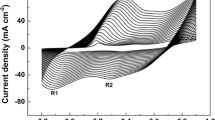

Figure 5b shows the plot of specific capacitance of P-1, P-2, P-3 and P-4 calculated from CV curves using relations 1 and 3. The P-3 exhibited a maximum specific capacitance as 164 F g−1 at a scan rate of 50 mV s−1. The P-1, P-2 and P-4 exhibited specific capacitance values as 69, 125 and 84 F g−1 respectively. To see the scan rate dependence, the P-3 was subjected at different scan rates from 5 to 100 mV s−1 as shown in Fig. 5c. It shows that the non-rectangular CV current response increased with the scan rate indicating the evolution of charge storage is pseudocapacitive in origin [38]. Also, it is observed that the oxidation and reduction peaks get shifted towards higher and lower potentials with increasing scan rates ascribed to the polarization effect [10]. Kuila et al. [63] previously explained the detail charge storage mechanism in the PANI. The total electric charge storing in a typical electrode is the addition of the surface capacitive charge due to the double layer transition and the faradaic charge due to the redox transitions in an ionic diffusion process. In order to understand the charge storage contribution from CV, the power law relation is used which is given by [64].

where i(V) is the voltage-dependent current value for a given scan rate v. Both a and b are the adjustable parameters. The b values are estimated from the slope of log i versus log v. If b = 1, the charge storage is purely surface capacitive and for b = 0.5, the charge storage is diffusion controlled capacitive. Figure 5d shows the b values of P-3 calculated using relation 5. The estimated b-values during the charging/anodic scan (0.2–0.8 V) and during the discharging/cathodic scan (− 0.2 to 0.4 V) are shown in Fig. 5d. During the charging process, b values increased from 0.53 (0.2 V) to 0.91 (0.7 V) indicating involvement of the diffusion capacitive transitions at initial potentials and the surface capacitive transitions at higher potentials in the PANI. Maximum b value occurred at a potential of 0.7 V which is more than the oxidation potential of the PANI as seen in CV (0.2–0.6 V). This indicates that after reaching the oxidation potential, the surface capacitive transitions are more involved in the charge storage process. However, during the discharging process, the b values increased from 0.59 (0.4 V) to 0.88 (− 0.1 V) indicating involvement of the diffusion capacitive transitions at initial potentials and the surface capacitive transitions at lower potentials in the PANI. Also, similar to the charging process during the discharging process, the surface capacitive reactions are more involved after reaching the reduction potential. Inset of Fig. 5d[i] shows the plot of log i versus log v for − 0.1 V(b = 0.88) and 0.7 V (b = 0.91) with its linear fitted curve. For the analytical study, the current contribution at given potential can be given by [64, 65]

where, k1v and k2v1/2 are associated with the surface capacitive current contribution and diffusion-controlled intercalation current contribution. The values of k1 and k2 could be calculated by measuring the slope and the intercept of Eq. 7.

The surface capacitive contribution in CV curve of the P-3 at 50 mV s−1 is shown in the inset of Fig. 5d[ii]. It estimated 48.7% of surface capacitive current contribution (shaded area) in the total current (solid line) ascribing the pseudocapacitive electrochemical property of the PANI.

The charge–discharge profile of P-3 at different constant current densities from 0.2 to 1.0 mA cm−2 are shown in Fig. 6a. The nonlinear charge–discharge profile at the all current densities attributed to the pseudocapacitive electrical properties of PANI [50, 55, 60]. The initial voltage drop in the discharge curve is associated with the high internal resistance of the P-3 [59]. Due to the non-linear discharge profile of PANI, its electrical charge storage can be represented by both Cs and Qd as given in Eqs. 2, 3 and 4. Estimated Cs and Qd values of P-3 from the GCD curves are shown in Fig. 6b. The maximum value of Cs is estimated as 710 F g−1 at 0.2 mA cm−2 and other estimated values of Cs are 616, 553, 527 and 521 F g−1 for 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 and 1.0 mA cm−2 respectively. In further, the maximum value of Qd is estimated as 119 mAh g−1 at 0.2 mA cm−2 and other estimated values of Qd are 103, 95, 89, 86 mAh g−1 at 0.4, 0.6, 0.8 and 1.0 mA cm−2 respectively. In previous studies Chougale et al. [32] reported 590 F g−1, Dhawale et al. [66] reported 503 F g−1, Sivaraman et al. [67] reported 480 F g−1, Khdary et al. [68] reported 532 F g−1, Guan et al. [69] reported 548 F g−1, Yan et al. [70] reported 470 F g−1 for PANI. The estimated specific capacitance of 710 F g−1 is more than previously reported studies ascribed to the unique porous nanograin/nanofiber morphology of PANI.

a The galvanostatic charge discharge curves of P-3 at different current densities from 0.2 to 1.0 mA cm−2, b Plot of specific capacitance and specific discharge capacity of P-3 at different current densities from 0.2 to 1.0 mA cm−2, c The specific capacitance of P-3 at different number of CV cycles, d The Nyquist plot of P-3 after 1st and 1000th CV cycles, inset shows the fitted equivalent circuit diagram and magnified view of Nyquist plots

The stability of the P-3 was studied for 1000 CV cycles at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1. The estimated specific capacitance values with the number of CV cycles are shown in Fig. 6c. The amount of 52.5% capacity retention is observed after 1000 cycles. This electrochemical degradation of the P-3 may be associated with the mechanical stress induced during the charging and discharging process leads to the dissolution of PANI in acidic media [71, 72]. In further analysis, the EIS of P-3 was performed after 1st and 1000th cycle at a frequency range of 106–100 Hz with an amplitude of 5 mV; respective Nyquist plots are shown in Fig. 6d with the fitted equivalent circuit diagram is shown in the inset. The curve is semicircular in the high frequency region and inclined at the low frequency region. The intercept of the curve on real impedance (Z′) represents a combined resistance of the electrode material and contact resistance at the interface between the electrode material-current collector termed as equivalent series resistance (ESR) or solution resistance (RS). The diameter of the curve semicircle at high frequency ascribed to the charge transfer resistance (RCT) at the interface of the electrode material and the electrolyte. The slope of 45° portion of the curve represents a Warburg resistant (ZW) associated with the frequency dependent ion diffusion in the vicinity of the electrode surface. CPE-1 defines the pseudocapacitance of active material. RL and CPE-2 are the voltage dependent charge transfer components placed parallel in the circuit [33]. The RS value of both 1st and 1000th curves are nearly 1 Ω as shown in the inset of Fig. 6d. However, the RCT value of 1st and 1000th curves are 323 and 526 Ω respectively. The increase in the RCT value after the 1000th cycle is attributed to the decrease in the conductivity of PANI due to the deprotonation over long tome immersion [73, 74]. In previous studies, Hui et al. prepared the PANI electrode by the pressing composition mixture of PANI nanofiber powder, acetylene black and poly(tetrafluoroethylene) onto stainless steel mesh which exhibited RS values of 1.63 Ω [69]. Li et al. [75] prepared the PANI electrode by drop casting prepared PANI on the glassy carbon which exhibited the RS values in the range of 5–8 Ω. In another study, Li et al. [76] prepared the PANI electrode by pressing the composition mixture of prepared PANI powder onto the Ni-mesh which exhibited the RS values between of 5–7 Ω. Poli et al. prepared the PANI on a carbon fiber felt which exhibited the RS values of 1.2–1.8 Ω [77]. Here, the PANI exhibited RS value of 1 Ω indicates formation of good electrical contact between SS and PANI. However, the large value of RCT can be ascribed to the major contribution of the diffusive intercalation charge transfer process in PANI as depicted in above electrochemical studies.

4 Conclusion

In conclusion, a simple, inexpensive SILAR method is successfully employed for the synthesis of unique mixed nanograin/nanofiber structured PANI on the inexpensive SS current collector. The FE-SEM along with XRD, FT-IR studies confirmed the formation of porous compact nanograin/nanofiber nanostructured PANI. The PANI prepared at 30 SILAR cycles exhibited a maximum specific capacitance of 710 F g−1 at a current density of 0.2 mA cm−2 with specific discharge capacity of 119 mAh g−1 in 1 M H2SO4. The electrochemical studies revealed that the total current contribution during the charging and discharging process in the PANI are initiated by the faradaic diffusion process due to the intercalation of electrolyte ions in the unique nanograin/nanofiber structure and later are dominated by the surface capacitive non-faradaic process after reaching the oxidation–reduction potential. This simple, room temperature synthesis method is very useful for the fabrication of porous PANI electrodes for pseudocapacitive energy storage application.

References

Luo X, Wang J, Dooner M, Clarke J (2015) Overview of current development in electrical energy storage technologies and the application potential in power system operation. Appl Energy 137:511–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.09.081

Talhar AS, Bodkhe SB (2019) The global survey of the electrical energy distribution system: a review. Int J Electr Comput Eng 9:2247–2255. https://doi.org/10.11591/ijece.v9i4.pp2247-2255

Chen K, Zhao F, Hao H, Liu Z (2019) Selection of lithium-ion battery technologies for electric vehicles under China’s new energy vehicle credit regulation. Energy Procedia. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2019.01.987

Dubal D, Jagadale A, Chodankar NR, Kim D, Gomez-Romero P, Holze R (2018) Polypyrrole nanopipes as a promising cathode material for Li-ion batteries and Li-ion capacitors: two-in-one approach. Energy Technol 7:ente.201800551. https://doi.org/10.1002/ente.201800551

Nagai H, Morita M, Satoh K (2016) Development of the Li-ion battery cell for hybrid vehicle. https://doi.org/10.4271/2016-01-1207

Ben Amira I, Guermazi A, Lahyani A (2018) Lithium-ion battery/supercapacitors combination in backup systems. In: 15th international multi-conference system signals devices, SSD 2018, IEEE, 2018, pp 1117–1121. https://doi.org/10.1109/ssd.2018.8570567

Jabbour N, Tsioumas E, Koseoglou M, Mademlis C (2019) Highly reliable monitoring and equalization in a hybrid energy storage system with batteries and supercapacitors for electric motor drives in building applications. In: 2018 IEEE 4th southern power electronics conference, SPEC 2018, IEEE, 2019, pp 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1109/spec.2018.8636029

Cohen IJ, Wetz DA, Heinzel JM, Dong Q (2015) Design and characterization of an actively controlled hybrid energy storage module for high-rate directed energy applications. IEEE Trans Plasma Sci 43:1427–1433. https://doi.org/10.1109/TPS.2014.2370053

Dubal DP, Abdel-Azeim S, Chodankar NR, Han Y-K (2019) Molybdenum nitride nanocrystals anchored on phosphorus-incorporated carbon fabric as a negative electrode for high-performance asymmetric pseudocapacitor. IScience 16:50–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2019.05.018

Maile NC, Shinde SK, Patil RT, Fulari AV, Koli RR, Kim D-Y, Lee DS, Fulari VJ (2019) Structural and morphological changes in binder-free MnCo2O4 electrodes for supercapacitor applications: effect of deposition parameters. J Mater Sci Mater Electron 30:3729–3743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-018-00655-5

Dubal DP, Chodankar NR, Kim D-H, Gomez-Romero P (2018) Towards flexible solid-state supercapacitors for smart and wearable electronics. Chem Soc Rev 47:2065–2129. https://doi.org/10.1039/C7CS00505A

Vangari M, Pryor T, Jiang L (2013) Supercapacitors: review of materials and fabrication methods. J Energy Eng 139:72–79. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)EY.1943-7897.0000102

Liu P, Yan J, Guang Z, Huang Y, Li X, Huang W (2019) Recent advancements of polyaniline-based nanocomposites for supercapacitors. J Power Sources 424:108–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.03.094

Sen T, Mishra S, Shimpi NG (2016) Synthesis and sensing applications of polyaniline nanocomposites: a review. RSC Adv 6:42196–42222. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6ra03049a

Tian Z, Yu H, Wang L, Saleem M, Ren F, Ren P, Chen Y, Sun R, Sun Y, Huang L (2014) Recent progress in the preparation of polyaniline nanostructures and their applications in anticorrosive coatings. RSC Adv 4:28195. https://doi.org/10.1039/c4ra03146f

Gaponik NP, Talapin DV, Rogach AL (1999) A light-emitting device based on a CdTe nanocrystal/polyaniline composite. Phys Chem Chem Phys 1:1787–1789. https://doi.org/10.1039/a808619b

Bhadra S, Khastgir D, Singha NK, Lee JH (2009) Progress in preparation, processing and applications of polyaniline. Prog Polym Sci 34:783–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PROGPOLYMSCI.2009.04.003

Prasankumar T, Wiston BR, Gautam CR, Ilangovan R, Jose SP (2018) Synthesis and enhanced electrochemical performance of PANI/Fe3O4 nanocomposite as supercapacitor electrode. J Alloys Compd 757:466–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.05.108

Chen Y, Zhang Q, Jing X, Han J, Yu L (2019) Synthesis of Cu-doped polyaniline nanocomposites (nano Cu@PANI) via the H2O2-promoted oxidative polymerization of aniline with copper salt. Mater Lett 242:170–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2019.01.143

Almuntaser FMA, Baviskar PK, Majumder S, Tarkas HS, Sali JV, Sankapal BR (2019) Role of polyaniline thickness in polymer-zinc oxide based solid state solar cell. Mater Sci Eng B Solid State Mater Adv Technol 244:23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mseb.2019.04.020

Gaikwad G, Patil P, Patil D, Naik J (2017) Synthesis and evaluation of gas sensing properties of PANI based graphene oxide nanocomposites. Mater Sci Eng B Solid State Mater Adv Technol 218:14–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mseb.2017.01.008

Govindaraj Y, Parida S (2019) Autogenous chemical and structural transition and the wettability of electropolymerized PANI surface. Appl Surf Sci 481:174–183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.03.075

Sivakkumar SR, Kim WJ, Choi J-A, MacFarlane DR, Forsyth M, Kim D-W (2007) Electrochemical performance of polyaniline nanofibres and polyaniline/multi-walled carbon nanotube composite as an electrode material for aqueous redox supercapacitors. J Power Sources 171:1062–1068. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2007.05.103

Deshmukh PR, Patil SV, Bulakhe RN, Sartale SD, Lokhande CD (2016) SILAR deposited porous polyaniline–titanium oxide composite thin film for supercapacitor application. Mater Today Commun 8:205–213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mtcomm.2016.07.002

Deshmukh PR, Patil SV, Bulakhe RN, Sartale SD, Lokhande CD (2014) Inexpensive synthesis route of porous polyaniline–ruthenium oxide composite for supercapacitor application. Chem Eng J 257:82–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2014.06.038

Kulkarni SB, Joshi SS, Lokhande CD (2011) Facile and efficient route for preparation of nanostructured polyaniline thin films: schematic model for simplest oxidative chemical polymerization. Chem Eng J 166:1179–1185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cej.2010.12.032

Lindroos S, Leskelä M (2000) Growth of zinc peroxide (ZnO2) and zinc oxide (ZnO) thin films by the successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction—SILAR—technique. Int J Inorg Mater 2:197–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1466-6049(00)00017-9

Su Z, Sun K, Han Z, Liu F, Lai Y, Li J, Liu Y (2012) Fabrication of ternary Cu–Sn–S sulfides by a modified successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction (SILAR) method. J Mater Chem 22:16346–16352. https://doi.org/10.1039/c2jm31669b

Perez PNG, Sino PAL, Herrera MU, Tapia AKG (2018) Conducting properties of polyaniline emeraldine salt on paper in the low-frequency region. Mater Sci Forum 923:72–76

Arejola GPJDV, Herrera MU (2018) Polyaniline emeraldine salt molecules coated on polyethylene board using SILAR technique. Key Eng Mater 775:311–316

Patil BH, Gund GS, Lokhande CD (2014) Influence of surfactant on the morphology and supercapacitive behavior of SILAR-deposited polyaniline thin films. Ionics (Kiel) 21:191–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-014-1146-8

Chougale UM, Thombare JV, Fulari VJ, Kadam AB (2013) Synthesis of polyaniline nanofibres by SILAR method for supercapacitor application. In: 2013 international conference on energy efficient technologies for sustainability, ICEETS 2013, pp 1078–1083. https://doi.org/10.1109/iceets.2013.6533537

Maile NC, Shinde SK, Koli RR, Fulari AV, Kim DY, Fulari VJ (2019) Effect of different electrolytes and deposition time on the supercapacitor properties of nanoflake-like Co(OH)2 electrodes. Ultrason Sonochem 51:49–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.09.003

Barakzehi M, Montazer M, Sharif F, Norby T, Chatzitakis A (2019) A textile-based wearable supercapacitor using reduced graphene oxide/polypyrrole composite. Electrochim Acta 305:187–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2019.03.058

Pandit B, Dubal DP, Sankapal BR (2017) Large scale flexible solid state symmetric supercapacitor through inexpensive solution processed V2O5 complex surface architecture. Electrochim Acta 242:382–389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2017.05.010

Laheäär A, Przygocki P, Abbas Q, Béguin F (2015) Appropriate methods for evaluating the efficiency and capacitive behavior of different types of supercapacitors. Electrochem Commun 60:21–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elecom.2015.07.022

Wu T-F, Hong J-D (2016) Humidity sensing properties of transferable polyaniline thin films formed at the air–water interface. RSC Adv 6:96935–96941. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6RA20536D

Deshmukh PR, Bulakhe RN, Pusawale SN, Sartale SD, Lokhande CD (2015) Polyaniline–RuO2 composite for high performance supercapacitors: chemical synthesis and properties. RSC Adv 5:28687–28695. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4RA16969G

Chaudhari KB, Gosavi NM, Deshpande NG, Gosavi SR (2016) Chemical synthesis and characterization of CdSe thin films deposited by SILAR technique for optoelectronic applications. J Sci Adv Mater Dev 1:476–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsamd.2016.11.001

Ghosh B, Das M, Banerjee P, Das S (2008) Fabrication of SnS thin films by the successive ionic layer adsorption and reaction (SILAR) method. Semicond Sci Technol 23:125013. https://doi.org/10.1088/0268-1242/23/12/125013

Ramírez-Esquivel OY, Mazón-Montijo DA, Montiel-González Z, Aguirre-Tostado FS (2017) Deposition of highly crystalline covellite copper sulphide thin films by SILAR. Phys Status Solidi 214:1700500. https://doi.org/10.1002/pssa.201700500

Maile NC, Mahadik SB, Takale MV, Fulari VJ (2019) Surface deformation studies of MnO2 film by double exposure digital holographic interferometry technique. Mater Res Express 6:045204. https://doi.org/10.1088/2053-1591/aafab2

Higashimura H, Kobayashi S (2004) Oxidative polymerization. Encycl Polym Sci Technol. https://doi.org/10.1002/0471440264.pst226

Li Y, Wang Y, Jing X, Zhu R (2011) Early stage pH profile: the key factor controlling the construction of polyaniline micro/nanostructures. J Polym Res 18:2119–2131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10965-011-9622-6

Yusoff II, Rohani R, Mohammad AW (2016) Investigation of the formation characteristics of polyaniline and its application in forming free-standing pressure filtration membranes. J Polym Res 23:177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10965-016-1068-4

Maile NC, Patil RT, Shinde SK, Kim D-Y, Fulari AV, Lee DS, Fulari VJ (2019) Facial growth of Co(OH)2 nanoflakes on stainless steel for supercapacitors: effect of deposition potential. J Mater Sci Mater Electron 30:5555–5566. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-019-00849-5

Shanmugavadivel M, Violet Dhayabaran V, Subramanian M (2017) Fabrication of a novel polymer nanohybrid electrode material PANI-BaMnO3 for high power supercapacitor application. Port Electrochim Acta 35:225–232. https://doi.org/10.4152/pea.201704225

Subramanian E, Dhana Ramalakshmi R, Vijayakumar N, Sivakumar G (2012) Hybrid composite materials of anatase titania and conducting polyaniline: properties and chemical sensor application. Indian J Eng Mater Sci 19:237–244

Ahirrao DJ, Jha N (2017) Polyaniline–manganese dioxide nanorods nanocomposite as an electrode material for supercapacitors, 050168. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4980401

Gawri I, Khatta S, Singh KP, Tripathi SK (2016) Synthesis and characterization of polyaniline as emeraldine salt, 020287. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4946338

Sydulu Singu B, Srinivasan P, Pabba S (2011) Benzoyl peroxide oxidation route to nano form polyaniline salt containing dual dopants for pseudocapacitor. J Electrochem Soc 159:A6–A13. https://doi.org/10.1149/2.036201jes

Lakshmi RV, Bera P, Chakradhar RPS, Choudhury B, Pawar SP, Bose S, Nair RU, Barshilia HC (2019) Enhanced microwave absorption properties of PMMA modified MnFe2O4–polyaniline nanocomposites. Phys Chem Chem Phys 21:5068–5077. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8CP06943C

Patil SL, Pawar SG, Chougule MA, Raut BT, Godse PR, Sen S, Patil VB (2012) Structural, morphological, optical, and electrical properties of PANi–ZnO nanocomposites. Int J Polym Mater Polym Biomater 61:809–820. https://doi.org/10.1080/00914037.2011.610051

Athira AR, Vimuna VM, Vidya K, Xavier TS (2018) Nanotubular polyaniline electrode for supercapacitor application, 030141. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.5032476

Jamadade VS, Dhawale DS, Lokhande CD (2010) Studies on electrosynthesized leucoemeraldine, emeraldine and pernigraniline forms of polyaniline films and their supercapacitive behavior. Synth Met 160:955–960. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.synthmet.2010.02.007

Chen W, Rakhi RB, Alshareef HN (2013) Facile synthesis of polyaniline nanotubes using reactive oxide templates for high energy density pseudocapacitors. J Mater Chem A. 1:3315. https://doi.org/10.1039/c3ta00499f

Butoi B, Groza A, Dinca P, Balan A, Barna V (2017) Morphological and structural analysis of polyaniline and poly(o-anisidine) layers generated in a DC glow discharge plasma by using an oblique angle electrode deposition configuration. Polymers (Basel). 9:732. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym9120732

Xing C, Zhang Z, Yu L, Zhang L, Bowmaker GA (2014) Electrochemical corrosion behavior of carbon steel coated by polyaniline copolymers micro/nanostructures. RSC Adv 4:32718. https://doi.org/10.1039/C4RA05826G

Cho S, Shin KH, Jang J (2013) Enhanced electrochemical performance of highly porous supercapacitor electrodes based on solution processed polyaniline thin films. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 5:9186–9193. https://doi.org/10.1021/am402702y

Kurra N, Wang R, Alshareef HN (2015) All conducting polymer electrodes for asymmetric solid-state supercapacitors. J Mater Chem A 3:7368–7374. https://doi.org/10.1039/C5TA00829H

Chang C-M, Hu Z-H, Lee T-Y, Huang Y-A, Ji W-F, Liu W-R, Yeh J-M, Wei Y (2016) Biotemplated hierarchical polyaniline composite electrodes with high performance for flexible supercapacitors. J Mater Chem A 4:9133–9145. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6TA01781A

Zeng S, Chen H, Cai F, Kang Y, Chen M, Li Q (2015) Electrochemical fabrication of carbon nanotube/polyaniline hydrogel film for all-solid-state flexible supercapacitor with high areal capacitance. J Mater Chem A 3:23864–23870. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ta05937b

Kuila BK, Nandan B, Böhme M, Janke A, Stamm M (2009) Vertically oriented arrays of polyaniline nanorods and their super electrochemical properties. Chem Commun. https://doi.org/10.1039/b912513b

Wang J, Polleux J, Lim J, Dunn B (2007) Pseudocapacitive contributions to electrochemical energy storage in TiO2 (anatase) nanoparticles. J Phys Chem C 111:14925–14931. https://doi.org/10.1021/jp074464w

Dubal DP, Abdel-Azeim S, Chodankar NR, Han Y-K (2019) Molybdenum nitride nanocrystals anchored on phosphorus-incorporated carbon fabric as a negative electrode for high-performance asymmetric pseudocapacitor. iScience. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.isci.2019.05.018

Dhawale DS, Vinu A, Lokhande CD (2011) Stable nanostructured polyaniline electrode for supercapacitor application. Electrochim Acta 56:9482–9487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2011.08.042

Sivaraman P, Kushwaha RK, Shashidhara K, Hande VR, Thakur AP, Samui AB, Khandpekar MM (2010) All solid supercapacitor based on polyaniline and crosslinked sulfonated poly[ether ether ketone]. Electrochim Acta 55:2451–2456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2009.12.009

Khdary NH, Abdesalam ME, El Enany G (2014) Mesoporous polyaniline films for high performance supercapacitors. J Electrochem Soc 161:63–68. https://doi.org/10.1149/2.0441409jes

Guan H, Fan LZ, Zhang H, Qu X (2010) Polyaniline nanofibers obtained by interfacial polymerization for high-rate supercapacitors. Electrochim Acta 56:964–968. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2010.09.078

Yan Y, Cheng Q, Wang G, Li C (2011) Growth of polyaniline nanowhiskers on mesoporous carbon for supercapacitor application. J Power Sources 196:7835–7840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpowsour.2011.03.088

Kim BC, Kwon JS, Ko JM, Park JH, Too CO, Wallace GG (2010) Preparation and enhanced stability of flexible supercapacitor prepared from Nafion/polyaniline nanofiber. Synth Met 160:94–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.synthmet.2009.10.011

Dhawale DS, Salunkhe RR, Jamadade VS, Dubal DP, Pawar SM, Lokhande CD (2010) Hydrophilic polyaniline nanofibrous architecture using electrosynthesis method for supercapacitor application. Curr Appl Phys 10:904–909. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cap.2009.10.020

Hao Q, Xia X, Lei W, Wang W, Qiu J (2015) Facile synthesis of sandwich-like polyaniline/boron-doped graphene nano hybrid for supercapacitors. Carbon N Y 81:552–563. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.carbon.2014.09.090

Brožová L, Holler P, Kovářová J, Stejskal J, Trchová M (2008) The stability of polyaniline in strongly alkaline or acidic aqueous media. Polym Degrad Stab 93:592–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2008.01.012

Li T, Zhou Y, Liang B, Jin D, Liu N, Qin Z, Zhu M (2017) One-pot synthesis and electrochemical properties of polyaniline nanofibers through simply tuning acid–base environment of reaction medium. Electrochim Acta 249:33–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2017.07.177

Li T, Qin Z, Liang B, Tian F, Zhao J, Liu N, Zhu M (2015) Morphology-dependent capacitive properties of three nanostructured polyanilines through interfacial polymerization in various acidic media. Electrochim Acta 177:343–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2015.03.169

Dos Santos Poli AK, Caetano GMD, Vargas LR, Gama AM, Baldan MR, Gonçalves ES (2017) Electrosynthesis of polyaniline on carbon fiber felt: influence of voltammetric cycles on electroactivity. J Electrochem Soc 164:D631–D639. https://doi.org/10.1149/2.1521709jes

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Basic Science Research Program for financial assistance through National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2018R1A6A1A03024962).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Maile, N.C., Shinde, S.K., Patil, K.S. et al. Capacitive property studies of inexpensive SILAR synthesized polyaniline thin films for supercapacitor application. SN Appl. Sci. 1, 1333 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1403-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-019-1403-6