Abstract

Over the past decades, researchers have recognized a need to develop more suitable forensic interview protocols to meet children’s right to receive improved and adapted communication. This study examines to what extent a relatively novel implementation of an investigative protocol conducted by highly trained Norwegian police investigators helps children (n = 33), 3–15 years of age, to report more detailed information from a criminal allegation than a previous protocol. Additionally, we investigated the bidirectional dynamics between interviewees and interviewers. We predicted that children’s spontaneous recollection would elicit more open-ended and focused questions from interviewers, and increase their likelihood of posing more open questions. We expected wh-questions to produce more central details regarding the abuse, which in turn allows the interviewers to resist employing suggestive and leading questioning. Results confirm an enriched communication after open-ended questions compared to suggestive and closed questions. Specifically, children reported more detailed central information regarding the abuse after cued recall and wh-questions (ps < .001), and interviewers followed up with more facilitators when children reported details (ps < .001). When the child was reluctant (e.g., said no) or a brief yes, interviewers produced more suggestive questions (ps < .01). We conclude that children may need more communication aids to recount their stressful experiences in an investigative context than what traditional interview protocols provide.

Similar content being viewed by others

Over the past few decades, a storm of criticism has erupted in scientific journals and conventional media regarding the misuse of child witnesses because of poorly performed forensic interviews (Ceci and Bruck 1995; Howe and Knott 2015). Consensus has been established regarding the worst of these forensic interview practices, and many improvements have been made in accepted best practice. Today, it is well documented that the productivity in children’s reports increases when the interviewer employs research-based interviewing techniques focused on open-ended questioning (Aldridge and Cameron 1999; Brown and Lamb 2015; Faller 2015; Lamb et al. 2008; for an overview, see Saywitz et al. 2018). Furthermore, when interviewed about a non-traumatic event, children have reported feeling more listened to and better equipped to tell their stories when asked open-ended versus closed questions (Brubacher et al. 2019b). However, concern still exists regarding the potential consequences of certain practices, such as interview delay or even breaks during an interview, both of which might reduce the accuracy of children’s reports but are seen as necessary to provide the extra time to plan the interview carefully (e.g., Gjellan and Hirsti 2018).

Practitioners, on the other hand, report concerns about some aspects of structured protocols (e.g., see Ernberg et al. 2016; Magnusson et al. 2020). The investigative context requires that practitioners elicit detailed accounts from children, including personal pronouns and perceptual details. To meet these demands, practitioners claim they need more child-appropriate approaches, including an increased focus on flexibility, rapport building, repeated interviewing and breaks, and the use of communication aids to facilitate the reports of younger children and vulnerable witnesses (e.g., individuals with intellectual disabilities) (Brubacher et al. 2019a, b; Langballe and Davik 2017). During criminal investigations involving children, there are also legislative demands which might pose a dilemma to some research-based interview strategies. An important yet not widely appreciated component of children’s rights concerns their fundamental right to be heard in matters that affect their lives and well-being, as acknowledged in the Convention on the Rights of the Child (Article 12). In Norway, children also have the right to be informed of the reason that they are appointed as a witness in a case. Child forensic interviewing in child victim and witness cases is a significant part of children’s rights from this perspective.

This article describes research on a Norwegian approach to child forensic interviewing by police in actual child victim and child witness cases, including a sophisticated bidirectional statistical analysis of interviewers’ questions and children’s responses. As this was a field study, we are not able to report the accuracy of the children’s reports. Instead, we will focus on what questions and facilitators encourage an age-appropriate dialogue with the individual child, and examine the presence of personal pronouns and perceptual details in the children’s responses. From an exploratory perspective, we will also describe how children are informed of the reason that they were called to the police interview. Before we turn to our hypotheses, we first discuss which developmental and age prerequisites are needed for a child-appropriate interview, followed by the identification of a methodological missing link in former evaluations of forensic practice.

Developmental and Age Prerequisites Needed for a Child-Appropriate Interview

In Norway, the Police Authority has recently implemented a novel approach to forensic interviewing focused on child-appropriate interviewing strategies to be employed with younger children and vulnerable witnesses within a Scandinavian context. By child-appropriate, we refer to strategies in the structured interview protocol that include several child-adjusted interventions. These interventions are, for example, beginning the interview by giving the child an age-appropriate explanation of the subpoena, focusing on a higher level of initial and maintained rapport building throughout the interview, ground rules including the imperative to correct the interviewer, improved communication skills and use of developmentally appropriate language, the use of pictures, drawings, and some play materials to support verbal utterances, and a higher degree of flexibility in terms of breaks and multiple interviews.

The Subpoena

International legislation (e.g., European Convention on Human Rights) and Norwegian criminal law section 110 explicitly state that any witness (or suspect) should be provided information about the reason that he or she is called upon. In the Norwegian regulations for children and vulnerable witnesses (section 11), it is specifically stated that the investigator must provide such information. The information must be age-appropriate and adjusted to the circumstances in each case. Practitioners must meet this requirement with a careful balance. Telling the child-specific details about the case under investigation could result in suggestive influence. However, introducing the substantive phase with a broad open question (e.g., “What brings you here today?”) does not include such presumptions, but may sometimes be too vague for the child. Even stating, “I know you talked to your teacher/mother about some things that happened to you, please tell me what you talked about,” is not always enough to help the child focus on the target topic. Being even more concrete about the reason, “I know you talked to your teacher/mother about your stepfather and what he does to you,” may be regarded as suggestive because it supposes that something might have happened. Therein lies the dilemma between the legislation regarding human rights and the risk of influencing the witness. One aim of the present study was thus to examine the information provided to children concerning the purpose of their interview. Specifically, we intended to explore the type and amount of details about the criminal allegation provided in Norwegian forensic interviewers’ introductory statements attached to the subpoena.

Child-Appropriate Interventions: Rapport Building and Improved Communication Skills

As seen in the subpoena dilemma, the desire for child appropriateness must be carefully balanced with the need for accuracy, and some child-friendly strategies may increase recall productivity and accuracy while others might reduce it. The focus on wh-questions (e.g., what, when, who, where) as follow-up questions to information gained in the free recall phase has been established as a successful way of helping the child by providing more structure across the interview, and represents one strategy that might be considered a more child-appropriate approach (Saywitz and Camparo 2014). However, wh-questions can also be misused, depending on the phrasing of the questions (Ahern et al. 2018; Malloy et al. 2016). The use of facilitators defined as brief utterances to facilitate conversation and convey active listening (e.g., “Ok,” “Uh-huh,” “Mm”) has also been found to increase children’s productivity during interviews (McWilliams et al. 2019) and seems to represent a productive yet neutral child-friendly approach. Another strategy, unstructured observation and the use of play materials by psychologists who conducted forensic interviews, however, tended to be too child-friendly, resulting in a high frequency of questions based on erroneous information in which interviewers asked questions based on the child’s play behavior instead of asking questions based on children’s narratives (Melinder et al. 2010).

An interview is demanding in terms of both the discussion of sensitive topics and time duration. Taking this into consideration, and given the highly negative and even traumatic experiences of many children in the legal system, a secure and calm environment is considered particularly important during an investigative interview with children, to enable reliable information (Melinder et al. 2020). Allowing the child to take breaks during an interview is another procedure that may increase the quality of the interview and helps children and vulnerable witnesses sustain attention and motivation (Poole 2016).

Several productive interviewing protocols address the need to be child-friendly without being suggestive. For example, narrative elaboration (Saywitz and Camparo 2014), which introduces more rapport building, pictures for different relevant themes, imperatives to correcting the interviewer, and explanation of the legal process throughout, is one novel and promising protocol that elicits more correct information from 4- to 12-year-old children and reduces suggestibility. Also, the revised National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) protocol has proven to elicit an increased amount of detail that children provide relative to the standard protocol (Hershkowitz et al. 2014). However, the narrative elaboration protocol and the revised NICHD protocols have not so far been examined bidirectionally.

A novel approach that includes these child-appropriate interventions has been introduced in Norway, the Dialogical Communicative Model (DCM) (Gamst and Langballe 2004). As the DCM approach has never been evaluated, a second goal within the present study was to examine the effectiveness of this protocol in a sample of newly examined police officers who completed the program, and compare question types to former results of question types from an earlier Norwegian sample (Johnson et al. 2015) with DCM. A third and major aim was to evaluate the DCM in terms of quality and effectiveness, i.e., focusing on the bidirectional relationship.

Sequential Analysis of Bidirectional Relationships: A Missing Link

Previous field studies across the world have focused on the effect of different question types, and one of the most frequent findings is that few interviewers ask the most recommended open questions (Guadagno and Powell 2009; Hershkowitz et al. 2005; Johnson et al. 2015; Korkman et al. 2006; Sternberg et al. 2001). Feedback and training on investigative interviewing tend to increase the use of recommended strategies (Benson and Powell 2015; Cederborg et al. 2013; Cyr and Lamb 2009).

A methodological limitation in many studies is a conceptualization of interview quality that often lacks a specific focus on the mutual, bidirectional influences in the interaction between the interviewer and the interviewed child. Perhaps for technical or practical reasons, studies rarely utilize sophisticated analytical approaches that enable a more fine-grained analysis of dialogue quality, which is critical when working with vulnerable individuals (Saywitz et al. 2015). The bidirectional interaction between child and interviewer is an under-researched topic and a missing link in the child investigative perspective, and hence lacking in former scientific evaluations of forensic practice with a few exceptions.

Sequential analysis investigates the chance-corrected probability of specific patterns of interaction occurring between two or more agents (Bakeman and Quera 2011). These techniques have been used to examine forensic interviewers’ behavior in three previous studies (Gilstrap and Ceci 2005; Melinder and Gilstrap 2009; Wolfman et al. 2016). In the first such analyses, Gilstrap and Ceci (2005) applied sequential analyses to transcripts of actual forensic interviewers’ conversations with children about a staged event. The interviews were coded for specific types of interview techniques of interest to the forensic community because of their effectiveness in eliciting information and their potential for suggestion. Next, the interviews were coded for types of child statements that indicated responsiveness, details, and on-topic statements. In these analyses, the authors concluded that interviewers used leading questions selectively with children who were already denying, and that children were likely to remain consistent in their behaviors. The same approach was employed with a sample of forensic interviews of 4-year-old children who had been exposed to a staged and “strange” medical examination (Melinder and Gilstrap 2009). Of interest in this study was how child and interviewer characteristics influenced the dynamics of the interview and in what sense these bidirectional patterns could explain the outcome in terms of question type and replies. The authors noted that reluctant children who often said “no” or only “yes” or kept silent evoked more aggressive, suggestive strategies from interviewers. On the contrary, children who reported more details elicited the recommended questions. Recently, Wolfman et al. (2016) also used sequential analyses to study forensic interviews with children, and like the current study, applied these analytic techniques to forensic interviewers’ behaviors in actual forensic interviews. For the most part, they found results similar to both Gilstrap and Ceci (2005) and Melinder and Gilstrap (2009). However, one surprising difference was that they found that children’s response style was not predicted by the question posed to them. In this paper, we build further on this line of research and explore the ways in which the dynamics between interviewers and interviewees unfold and possibly affect interviewer question type and the quality of child replies.

The Present Study

The present study examined the quality of the interview and the effectiveness of the extended DCM in terms of children’s recollections with three main research questions. After completing their final exams, specially trained police investigators who underwent DCM child interviewing training delivered their transcripts and videotapes of interviews with children who consented to participate. Two reliable scorers coded all transcripts and videotapes for question types and child responses by employing a coding system developed for this study. For exploratory purposes, we firstly examined the interviewers’ introductory statements concerning how they described the purpose of the interviews to children following the legal requirements in Norway, (i.e., the subpoena). Secondly, we compared former results of question types from a Norwegian sample with those from the DCM. We also analyzed the children’s responses and examined the extent to which they reported details from the crime scene and personal information. The third and main aim of the present study was to conduct bidirectional analyses of forensic interviews with children using the DCM, which includes an enhanced rapport-building phase, communication tools, and taking breaks. We predicted that children’s spontaneous recollection would elicit more facilitators and open questions from interviewers. We predicted that these additional facilitators and open questions would lead to even more detailed information. We expected wh-questions to produce more central details regarding abuse and consequently support the interviewers’ attempts to resist suggestive and leading questioning.

Method

Ethical Considerations

The study was carried out in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and was reviewed and approved by the National Data Protection Regulation, the Ministry of Justice (e.g., the State Attorney), and the Council for Professional Confidentiality and Research. To be included in the study, both the police interviewers and the children’s legal guardians had to provide their informed written consent. Due to the sensitive nature of the material, the coding and data handling were carried out at the Police University College, where the materials were archived.

Participants

A total of 72 police officers consented to participation in the study. Nine officers quit the program before the final exam, leaving 63 officers. Due to lack of informed consent from 30 guardians (e.g., the legal authority who acts as the parental representative in cases where the parent is under investigation for the criminal act), 33 officers (ages 26–53, M = 36.94, SD = 7.40, 28 female) took part in the study. They all had three years of formal training as police officers, followed by the intensive DCM training course in interviewing young children and other vulnerable witnesses. The sample thus represents a highly educated interview force.

The data consisted of interviews with 33 children between the ages of 3 and 15 years (M = 9.42 years, SD = 3.85, 55% girls). The DCM interview is normally conducted when the witness is preschool-aged or is a chronologically older youth with intellectual disabilities that suggest a younger developmental age. The age range in our sample reflects this. The interviews were carried out from fall 2016 to spring 2018. A majority of the children were Caucasian (72.8%), followed by Middle Eastern Asian (18.2%) and African (9.1%). All participants spoke Norwegian.

Case Characteristics

The children were called as complainants in thirty of the interviews (90.9%), and as witnesses in the remaining three interviews (9.1%). The cases concerned alleged physical abuse (45.5%), sexual abuse (45.5%), or witnessing intimate partner violence (9.1%). A majority of the cases involved one suspect (81.8%), most commonly a biological parent (51.5%), followed by other relatives (9.1%), acquaintances (15.2%), teachers or trainers (15.2%), and strangers (9.1%). In total, 78.8% of the cases concerned a male suspect, 6.1% a female suspect, and 15.2% both a male and female suspect (in cases with multiple suspects). Twenty (60.6%) of the cases involved suspected repeated crimes, and 13 (39.4%) involved a single occasion.

The Dialogical Communication Model (DCM) with Additional Refinements

Training

The comprehensive training in DCM (Gamst and Langballe 2004) and a second level of sequential interviewing and a toolbox perspective (Langballe and Davik 2017; Saywitz et al. 2018) is delivered by pedagogues, child psychologists, professors in law, and experienced child police interviewers. Police officers with formal BA training including the KREATIV (e.g., the Norwegian version of the PEACE model, see Bull 2020; Bull and Rachlew 2019) undergo a two-week theoretical course to learn evidence-based strategies and practice their skills in role-playing activities. Students conduct a child interview under the supervision of a senior police officer specialized in child interviewing before they return to two separate weeks of training and for feedback on their first and second trial interviews that have been video recorded and transcribed. After these three supervised interviews, students take their exams. During the second level (e.g., the sequential interviewing), the students are provided with further strategies, such as sequencing of the interview, in-depth training in rapport building, the imperative to correct the interviewer, use of props and communication aids from the tool-box (e.g., age-appropriate language, drawings that are not used as evidence and are not “interpreted”), and the use of breaks. As in the first level, they again conduct trial interviews, get feedback from supervisors and teachers, and take a final exam with the same scope and demands as described above.

The Protocol

First, there is a preparation phase, which generally happens before the child appears at the interview and is used to collect other evidence, some of which might be used during the interview. The interview protocol then begins with an introduction and rapport-building phase. During this phase, with preschool-aged children, interviewers might use drawings. This phase merges into a sequence in which the interviewer explains the role of the interview and why there are cameras in the room, encourages the child to tell the truth in an age-adjusted manner, tells the child to say “do not know” to questions the child does not understand, and communicates the importance of correcting the interviewer. Then, the interviewer introduces the reason why they need to talk to the child, without mentioning details from the investigation, for instance, “I know you talked to your teacher about something that might have happened to you, and that is what we want to talk to you about today.” If the child does not reply, the interviewer provides further information about the conversation: “I know you talked about your mother and you said she did something, please tell me about that.” The interview continues with focused questions/cued recall questions regarding each detail that the child communicates. When all the details have been carefully explored, wh-questions might be asked. Finally, the interviewer closes the interview, talking about everyday activities (Langballe and Davik 2017).

Procedure

Upon the police officers’ first week of training, the first author introduced the study’s main aim (i.e., to examine forensic interviews), hiding the hypotheses, and asked for informed consent that included letting the research team analyze their exam interviews if they obtained informed consent from the child’s guardians. Police officers were asked to introduce the study to parents or guardians after the investigative interviewing was conducted, according to ethical approval. Here, the police officers provided guardians with a letter from the first author explaining the study and a letter of consent to sign. Police officers then brought the videotapes and the transcriptions to the Police University College for examination and further storage. The first author and main coder had access to these materials only at the Police University College due to the sensitivity of the data.

Coding

The interviewers’ question types and the children’s verbal and non-verbal responses were coded from the written transcripts and video recordings of the substantive phase of the interviews. Interviewer codes were developed from the Lamb et al. (1996, 2008) NICHD scoring protocol and the method used in a previous evaluation of Norwegian child interviews from 2002 to 2010 (Johnson et al. 2015). Child codes were inspired by Melinder and Gilstrap (2009) and adjusted to the specifics of the present study. The first author trained the main coder, who was naïve to the aim and hypotheses of the study, on the coding system. Initially, an interrater reliability analysis was carried out, whereas the main coder and the first author independently coded 20% (n = 7) of the material, including when the introductory statements and questions/responses during the substantive phase were first asked. An acceptable level of interrater reliability was achieved, with an overall Cohen’s kappa coefficient of .78 (range .69–1.0) for interviewer questions and .86 (range .71–1.0) for child utterances, see Table 1 for an overview. Disagreements were examined and resolved through discussion. The main coder thereafter coded the remaining material.

Subpoena: The Introductory Statements

The type and amount of detail in the introduction statements were coded following a method developed for the present study. Each introduction statement (defined as all initial information provided by the police regarding the purpose of the interview, cf. subpoena) was scored with regard to the presence or absence of each of the following pieces of central details about the criminal allegation: information about the suspect or suspects (e.g., “You are here today to talk about your older brother), the crime type (e.g., “and that he may have hurt you”), the location of the crime (e.g., “outside your school), the time of the crime (e.g., “around two weeks ago”), references to other disclosure recipients (e.g., “We heard that you may have talked to your teacher about something”), and references to other corroborative evidence (e.g., “Photos of the abuse”).

Interviewer Questions

All questions during the substantive phase were scored. We defined invitations as the broad open-ended questions inviting the child to give a free recall (e.g., “Tell me everything you remember”), open cued recall as focusing of a detail from the child’s own narrative (e.g., “You said he took his hand under your pyjamas, tell me more about that”), directive recall as open-ended follow-up questions starting with WH except from why, option-posing as those questions containing alternatives (e.g., “Is it at night or at day time”), yes/no as those questions with the only possible response as yes or no, suggestive as those asking for visualization (e.g., “Think back and see how he came into the room”), using pressure (e.g., “When you tell me, we will have an ice cream break” or “If you don’t tell, your sister might be at danger”), adding misleading information not mentioned by child (e.g., “So, she held the dog close to your leg,” when the child never said anything about a dog), repeating a question (e.g., if the interviewer repeated a directive question because the child did not respond the first time, the question was coded as directive, but if the child had provided a response and the interviewer repeated the same question, it was coded as suggestive), demonstrate as an invitation to show on a drawing, on the child’s body, on the interviewers body, or on a human body figure, clarifications as those asking to clarify the child’s utterance and close the clarification with a yes/no marking (e.g., “So, you say that first he touched your knee, and then he pushed you down”), facilitators as utterances that support the communication per se (e.g., “I see,” “hmm,” “OK”), off-topic as questions or comments regarding technical issues, child’s own off-topic themes (e.g., playmates, kindergarten, clothes, hobbies, if these are not central to the investigation), and finally non-scorable for utterances that we could not hear or understand semantically.

Child Utterances

All narrative information concerning the allegation provided by the child was scored. We defined yes as agreeing with the word “yes” or nodding, no with the word “no” or shaking head, details as all peripheral narratives about the allegation (e.g., “My sister had homework to do”), central details as those narratives describing the crime itself (e.g., “She hit me on my back”), I do not know and I do not remember for precisely that, clarification as the child’s explanation of any circumstances or event secondary to first mentioning (e.g., “I meant that he first put his hand here [demonstrating] and then he took hard on my arm” if the child first said “He put hand on me and then on arm”), off-topic when the child talked about the interview situation or other events that were not part of the allegation (e.g., “Can we take a break soon?”). For exploratory purposes, we also counted all utterances that included perceptual details reflecting sensory information (e.g., “They screamed”) and all utterances when a child used a personal pronoun to refer to other agents (e.g., “He”) or to him/herself (e.g., “I”).

Results

This study provides new data on well-trained Norwegian forensic interviewers’ competency to elicit relevant and detailed narratives from children, and it further enables us to discuss what we think of as a qualitative improvement in forensic interviews.

Subpoena: The Introductory Statements

For exploratory purposes, we analyzed the type of information revealed to children in the introductory statement regarding the purpose of the interview, i.e., the subpoena. The majority of interviewers gave information to the child about the person (78.8%) and location (57.6%) related to the suspected crime (e.g., “You are here today to talk about how you have it at home with your mum and dad”). Some (27.3%) also specified the time of the suspected abuse (e.g., “We are going to talk about something that happened earlier this summer”). In about two-fifths of the cases (42.4%), the interviewer informed the child that they had heard that the child had disclosed something to someone else (e.g., “I heard that you told your mother something and we are going to talk more about that today”). In a few cases (15.2%), the interviewer also informed the child about the suspected crime type under investigation (e.g., “You are here today because we are investigating whether ‘X’ has done anything of a sexual nature towards children or adolescents”). Lastly, in three cases (9.1%), the interviewer told the child about the presence of other evidence in the form of text messages, photos or videos of the abuse, or a confession from the suspect (e.g., “We are going to talk about Snapchat and some photos and videos that you have shared there”).

Frequencies of Interviewer Questions and Child Responses

Table 1 presents the percentages of interviewers’ questions during the substantive phase, which included 11,938 questions (resulting in a total of 23,876 turns between the interviewer and child). Open-ended invitations were frequently used, and although suggestive questions were employed, their frequency was not alarmingly high. Furthermore, it is worth noting that police officers made use of facilitators to a large degree, as well as of clarifications. These utterances should be regarded as improvements in terms of children’s rights because of the communicative value and hence the quality that these interventions added. Very few police officers’ questions or comments were scored as off-topic.

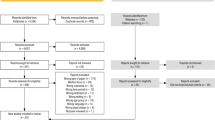

To answer our second question, we observed whether the intensive training on DCM affected the interviewers’ performance in terms of questions asked, compared to a former evaluation with a comparable age and similar gender distribution (Johnson et al. 2015Footnote 1). An inspection of Fig. 1 indicates that the trend in the amount of open-ended questions has increased, while closed questions have decreased.

We also examined the children’s responses as they evolved during the interviews´ substantive phase in 11,983 turns. As can be seen from Table 1, the children provided substantial information about central crime details such as specific actions, who did what, and how. Another important note is that the children’s recollections included very few numbers of “do not know” and “do not remember” answers, at the same time as the number of off-topic responses did not appear to be high. Furthermore, with regard to the utterances including perceptual details and personal pronouns, about a third of the utterances (30.1%) included personal pronouns, and 5.4% included descriptions about sensory information. However, we were mainly concerned with the communicative quality, the bidirectional relationship, between interviewers and interviewees.

The Dynamics between Interviewees and Interviewers

For the analyses of the dynamics between child and interviewer, we employed sequential analyses to predict behavior from interviewer to child and from child to interviewer. This analysis of behaviors directly following each other is called a Lag 1 analysis because we predict from one behavior directly to the next occurring behavior. In a Lag 1 analysis, a simple transitional probability can be calculated. This transitional probability states the likelihood that a behavior of interest (i.e., a target behavior) will follow another behavior of interest (i.e., the given behavior). This probability must be corrected for the possibility that the co-occurrence happened simply by chance. This correction is made using the base-rate occurrence of those two codes. To apply this correction, for each dyad in the sample, it is possible to compute Yule’s Q, which is what we did in the current analyses. Yule’s Q has two primary benefits: (1) it corrects for the probability that this pattern will happen by chance intersection, given the base-rate occurrence of the two codes in the sample, and (2) it applies a transformation such that the score can now be interpreted in the same way as Pearson’s correlation ranging from −1 to 1. For the interested reader, a more thorough explanation of Yule’s Q can be found in Bakeman and Quera (2011) and Yoder and Feurer (2000). Yule’s Qs can be averaged across the sample to give a sample-level description of the transitional probability, and Yule’s Qs can also be used individually with a non-parametric sign-test to evaluate whether the average sample-level Yule’s Q represents the trend across the sample rather than being an artifact created by a few extreme scores. In the current analyses, non-parametric sign-tests were used to indicate whether this transformed transitional probability represented the overall trend of the sample, that is, whether the Yule’s Qs of the majority of dyads were in the same direction as the mean.

In predictions for our Lag 1 analyses, we took note of former findings that children’s spontaneous recollection elicited more recommended questions such as facilitators and restating the child’s responses, which in turn led to more child production of detailed narratives. The current data confirm the predicted enriched communication after open-ended questions compared to suggestive and closed questions in terms of mean transitional probability. When predicting from interviewer to child behaviors (see Table 2), open-ended questions (i.e., invitations, open cued recall, open directive recall, facilitators) were followed by more central details about the criminal allegation than expected by chance. Closed questions (i.e., suggestive, option-posing, and y/n) were followed by more short answers (i.e., yes/no responses) than expected by chance. When predicting from child to interviewer behaviors (see Table 3), simple “no” responses were more likely than expected to be followed by suggestive questions but not by both open-ended or facilitators, while yes responses were more likely than chance to be followed by both suggestive questions and open-ended questions but not facilitators. Detailed child responses were more likely to be followed by facilitators from the interviewer.

Although both option-posing, y/n, and suggestive questions were more likely to be followed by no responses, children assented to option-posing and y/n questions but not suggestive questions more often than chance. These findings raised the question of longer patterns in the dialogue, which we explore in the following section.

Combining the findings from the Lag 1 analyses suggests the following patterns, see Figs. 2 and 3. If the coding scheme is simplified by considering interviewers’ questions as either closed or open and children’s responses as either short or detailed, by linking the Lag 1 analyses from interviewer to child with the Lag 1 analyses from child to interviewer, we can see how the enriched communication pattern (i.e., detailed responses by children) after open-ended questions perpetuates itself, with interviewers asking additional open-ended questions in response to these detailed responses.

Focusing on the closed-question dialogue pattern in Fig. 2, closed questions were followed by child short responses, but child short responses were not consistently followed by closed questions. By breaking down the closed-question category into question types and short responses into “yes” or “no” (see Fig. 3), we see that short responses provoked different interviewer behaviors depending on whether the short response was a “yes” or a “no,” as shown in Fig. 3. Short “no” responses following different types of closed questions tend to provoke additional closed questions – continuing the opposite, impoverished side of the enriched communication cycle.

Discussion

The position of children as witnesses has been reconsidered in most Western societies in recent years in light of advances in our knowledge about children’s cognitive and emotional development, but also due to novel demands being placed on the investigative system as a result of enhanced children’s rights and the evolution of modern legal practice (Wolpe and Goodman 2019; Council of Europe Convention). We examined whether these innovative methods affected the interviewers’ performance in terms of the questions asked and, more importantly, whether the interview quality was ultimately improved.

The Subpoena

This is the first study to report the type of introductory statements given to the individual child in order to provide information about the reason that the child is called to an interview with the police. Many interviewers gave information to the child about the person, location, and time of the suspected crime when they had such, thereby revealing central information. Although this might have affected the children’s report, the information had been obtained through other parts of the investigation, and according to ethical principles, it is a witness’s right to be informed. In some cases, where the interviewer referred to what the child had disclosed to someone else, a suggestive effect might be increased because it puts pressure on the child to repeat something that might have been false, without giving the child a chance to take it back (Ceci and Bruck 1995; Flin 1992). We would advise using only objective facts from former investigative steps when introducing the subpoena to the child.

Comparison to Former Study

Compared to former studies from Norway (Johnson et al. 2015), the UK (Sternberg et al. 2001), and Finland (Santtilla et al., 2004), we found that the trend in terms of questions asked is positive in our present sample. In the former sample from Norway (Johnson et al. 2015), interviewers asked fewer open-ended questions and more closed questions compared to the present sample. A main difference between the two time periods is the focused training on communication strategies and child-appropriate strategies for the interviewers (Langballe and Davik 2017).

We found clear evidence of the use of facilitators and clarifications, which are generally regarded as supportive in a conversational context (Walker 2013), and which are a logical consequence of the accentuation of children’s rights (Wolpe and Goodman 2019). However, it is doubtful whether clarifications of free recall by means of yes/no questions are desirable, as they narrow the scope of alternatives considerably. The clarifications were mostly connected to an almost compulsive trend of summarizing (e.g., clarifying) what the child had said during an earlier phase of the interview (“Before you said that he held his hand on your knee, was that so?”), and indicated, we believe, a wish to correctly understand the individual child. It may, however, force the child to repeat something the child did not mean or said wrongfully, or it may suggest a desirable answer. On a similar note, some of the suggestive utterances included failed attempts at clarifications, where the interviewers tried to summarize the child’s statement but added new information or distorted the original response from the child. We do not have any explanation for this practice but would recommend that future interviewer training highlight the importance of caution when summarizing content from the child witness.

Bidirectional Relationships

For the main purpose of our study, we were able to confirm what researchers have known for a long time: open-ended questions are the basic pillar of enriched communication. When we combined question types into open versus closed questions and child responses into short response versus details, a predictable pattern emerged. Closed questions were followed by short responses more often than chance, whereas open questions were followed by details. Details by the child were then followed by interviewer facilitations, while short responses were followed by a variety of follow-up probes, both closed and open. One type of closed question, option-posing and yes/no, was followed by both types of short responses (i.e., yes and no) while the other type of closed question, suggestive, was followed more often than expected by no responses. The latter may indicate an effect of the instruction to correct the interviewer, which has been recommended as part of the rapport-building sequence and is incorporated within the DCM (Saywitz and Camparo 2014). Both of these findings are similar to those of past sequential analyses (Gilstrap and Ceci 2005; Melinder and Gilstrap 2009), and we begin to see a consistent pattern in this literature.

Similarly, when predicting from child to adult, details were much more likely to be followed by supportive communication (i.e., facilitators). While short yes responses were generally followed by a variety of probes, short no responses were more likely to be followed by closed rather than open questions. These findings are again similar to past sequential analysis using similar coding schemes, but not to the most recent findings of Wolfman et al. (2016), who did not find that child behaviors provoked any particular pattern of adult behaviors. Wolfman et al. (2016) conceptualized child responses dichotomously as either responsive or non-responsive. Given that the other three sets of sequential analyses found different provoked interviewer behaviors depending on whether the child was denying or assenting and whether they were doing so with or without details, it is perhaps not surprising that the findings differ when the child responses are conceptualized in a way in which assent, denial, and details are combined into the same category. Future research could examine the way that different coding schemes affect our conclusions on this topic. Overall, we detected an ongoing adjustment to evidence-based forensic interviewing (Saywitz and Camparo 2014; Saywitz et al. 2018) and a more child-appropriate approach to children’s needs during forensic interviewing.

The children’s responses contained a surprisingly high number of both central and peripheral details, indicating a competency in the child that the legal system demands (Ernberg et al. 2018). Central information about actions and individuals involved with the crime under investigation is generally regarded as critical details that must be present in order to take charge. One difficulty with younger children is that they are not that specific, and need more directives and specific questioning to come out with details (e.g., use of open-ended cued recall, directive questions, and wh-questions). With the more updated protocols that exist, such follow-up questions are recommended (U.S. Department of Justice Program 2015). We want to emphasize that while the use of wh-questions may facilitate children’s witness abilities, practitioners need to keep in mind that wh-questions can be misused depending on the phrasing and content. For example, questions starting with “why” or “how” (e.g., “Why did he walk away”) can produce uninformative responses and even guessing from young children (Malloy et al. 2016). Future research is needed to better understand different nuances of wh-questions and their influence on children’s memory reports (Ahern et al. 2018).

We also noted references to personal pronouns and to own mental status or perceptual aspects by the children. Such utterances frequently appear in checklists and analyses of statements, and these utterances are often regarded as a sign of autobiographical quality (e.g., content-based criteria analyses (CBCA) and reality monitoring representing behaviors that are regarded as credible; Volbert and Steller 2014). Lastly, the relatively moderate number of off-topic responses we found may be another sign of well-performed interviews, with interviewers that adjusted their communication to the individual child’s age and needs. It is not unusual for judges to express reluctance to see the videotaped child interview during a trial, because of the impression that so much of the interview is off-topic. However, our finding in this respect speaks against this position. It is thus important to communicate this finding back to the legal authorities, who often remark that child interviews are seemingly off-topic and, therefore, not as interesting as evidence and not an effective use of their time.

Some Closing Remarks on Qualitative Interviewer Strategies

In most professional communication with children and other vulnerable individuals, basic ethical attitudes such as respect, care, understanding, and autonomy should guide practice. However, while professionals in clinical assessment and diagnostic practice use yes/no questions (e.g., “Does your child regularly express anger?”) to summarize and interpret symptoms and classify these (e.g., form a diagnose), forensic practice relies on the same ethical principles while avoiding using these types of closed questions, i.e., yes/no. Likewise, interpretations or body reading are not recommended in forensic practice, whereas they may well be employed in the clinic. What is healthy communication is thus defined differently depending on the context and the purpose of the professional contact. Because of the variety of professional contexts in which communication is employed, each type of communication must be professionalized into context-specific, basic principles through systematic training that includes theory, practice, legal context, and supervision/mentoring.

An important factor that may explain why the performance of the present police officers reached higher levels of professionalism and better adjustment to recommendations may lie in the comprehensive training program over one year with mandatory seminars and the supervision that child interviewers in Norway are offered. Interviewers in the present sample develop their communication style following a child-appropriate and ethical approach, using strategies that support the evolving dialogue and help memory retrieval processes (Brubacher et al. 2011; Saywitz et al. 2018). Specifically, through the rapport-building phase, the interviewer sets a pattern of healthy interaction that should be maintained throughout the interview (Hershkowitz et al. 2015; Price et al. 2013; Saywitz et al. 2015), and primes the behaviors in the following interview pattern (e.g., the substantive phase). Sometimes breaks within an interview, or even more than one non-duplicative interview, may be necessary with young and vulnerable children to adapt to the child’s communication style and to gain the traumatized child’s trust (Faller et al. 2010; La Rooy et al. 2010). In collaboration with staff from the children’s house where the interviews were performed, the police officers that conducted the interviews decided if and when such breaks were needed. Additionally, the officers received regular supervision from mentors and were enrolled in peer teams that met regularly for feedback and discussions – all in line with recommendations that were made long ago (Davies et al. 1996; Goodman and Melinder 2007) and have continued to be suggested (Wolfman et al. 2016).

Limitations

Some limitations should be mentioned. First, about half of the participating police officers succeeded in getting informed consent from parents or guardians, which was a requirement from the National Data Protection Regulation should the study be conducted. As a consequence, parts of our analyses were limited to descriptive statistics. Furthermore, the age range of the children was wide, and due to the limited sample, any potential age differences could not be statistically examined. Importantly, however, although we do not know the specific degree of the intellectual disability in our sample, all interviewees were assessed regarding need for adjustment to elementary or even preschool levels.

We did not analyze whether each of the specificities in the novel approach (e.g., extended rapport building, the toolbox materials, and the extra breaks) affected the children’s responses during the substantive phase. Because the DCM contains all of these strategies, interwoven throughout the interview, it was not possible to parse out the effects of each of these specificities. However, we did describe the information revealed to children in the introductory statement regarding the purpose of the interview. In our view, the extended introduction (e.g., the subpoena) may be the one most criticized due to its risk of influencing the child, especially the information with reference to others.

Another possible limitation in the present sample is that participants were well educated and had gone through several steps of training before they conducted the forensic interviews examined in this study. However, while we do not generalize the present study’s results to police officers’ competence worldwide, we underscore again the importance of professionals being informed by research-based practice and systematic feedback regarding their own performance.

Conclusions

With more than 30 years of research in child interviewing with a strong focus on, and analyses of, question type, it is now time for supplementary knowledge. As this study shows, interviewers need insight into the interview processes – how to form an effective and informed dialogue with vulnerable witnesses in accordance with human rights conditions. The present study further shows that compared to former observations of interviewer practice, improvements have been made. Further, children’s reports do not suffer from the use of a more child-appropriate approach, such as pictures and drawings to support verbal utterances, and sequencing the interview with breaks. On the contrary, we saw that a child-appropriate approach elicited details from the children, which in turn supported positive interviewing behaviors when analyzed bidirectionally. If the communication used is suggestive questioning, however, then the interview is no longer child-appropriate, and the child’s rights are at stake.

Notes

In the 2015 study, mean age of the children was 9.9 years for girls and 9.7 for boys range = 3.2–15.8, 76% girls.

References

Ahern, E. C., Andrews, S. J., Stolzenberg, S. N., & Lyon, T. D. (2018). The productivity of wh-prompts in child forensic interviews. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33, 2007–2015. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515621084.

Aldridge, J., & Cameron, S. (1999). Interviewing child witnesses: Questioning techniques and the role of training. Applied Developmental Science, 3, 136–147. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532480xads0302_7.

Bakeman, R., & Quera, V. (2011). Sequential analysis and observational methods for the Behavioural sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Benson, M. S., & Powell, M. B. (2015). Evaluation of a comprehensive interactive training system for investigative interviewers of children. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 21, 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000052.

Brown, D. A., & Lamb, M. E. (2015). Can children be useful witnesses? It depends how they are questioned. Child Development Perspectives, 9, 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12142.

Brubacher, S. P., Roberts, K. P., & Powell, M. (2011). Effects of practicing episodic versus scripted recall on children's subsequent narratives of a repeated event. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 17, 286–314. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022793.

Brubacher, S. P., Timms, L., Powell, M., & Bearman, M. (2019b). “She wanted to know the full story”: Children’s perceptions of open versus closed questions. Child Maltreatment, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/10775595188821730.

Brubacher, S. P., Poole, D. A., Dickinson, J. J., La Rooy, D., Szojka, Z. A., & Powell, M. B. (2019a). Effects of interviewer familiarity and supportiveness on children’s recall across repeated interviews. Law and Human Behavior. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000346.

Bull, R. (2020). Roar to “PEACE”: Is it a “tall story”? In R. Bull & I. Blandon-Gitlin (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of legal and investigative psychology. London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Bull, R., & Rachlew, A. (2019). Investigative interviewing: From England to Norway and beyond. In S. Barela, M. Fallon, G. Gaggioli, & J. Ohlin (Eds.), Interrogation and torture: Research on efficacy, and its integration with morality and legality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Casey, B.J. (2015). Beyond simple models of self-control to circuit-based accounts of adolescent. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 295–319. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015156.

Ceci, S. J., & Bruck, M. (1995). Jeopardy in the courtroom: A scientific analysis of children's testimony. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Cederborg, A.-C., Alm, C., da Silva Nises, D. L., & Lamb, M. E. (2013). Investigative interviewing of alleged child abuse victims: An evaluation of a new training programme for investigative interviewers. Police Practice & Research: An International Journal, 14, 242–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2012.712292.

Cyr, M., & Lamb, M. E. (2009). Assessing the effectiveness of the NICHD investigative interviewing protocol when interviewing French-speaking alleged victims of child sexual abuse in Quebec. Child Abuse & Neglect, 33, 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.04.002.

Convention on Rights of the Child (CRC) of 20 November 1989 art. 13, The Norwegian constitution og 17 May 1814 § 104, Child welfare act of 17 July 1992 nr. 100 § 1-6.

Davies, D., Cole, J., Albertella, L., Allen, K., & Kekevian, H. (1996). A model for conducting forensic interviews with child victims of abuse. Child Maltreatment, 1, 189–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559596001003002.

Ernberg, E., Magnusson, M., Landström, S., & Tidefors, I. (2018). Court evaluations of young children's testimony in child sexual abuse cases. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 23, 176–191. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12124.

Ernberg, E., Tidefors, I., & Landström, S. (2016). Prosecutors’ reflections on sexually abused preschoolers and their ability to stand trial. Child Abuse & Neglect, 57, 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.06.001.

Faller, K. C. (2015). Forty years of forensic interviewing of children suspected of sexual abuse, 1974-2014: Historical benchmarks. Social Sciences, 4, 34–65. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci4010034.

Faller, K. C., Cordisco-Steele, L., & Nelson Gardell, D. (2010). Allegations of sexual abuse of a child: What to do when a single forensic interview isn’t enough. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 19, 572–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2010.511985.

Flin, R., Boon, J., Knox, A., & Bull, R. (1992). The effect of a five-month delay on childrens and adults eyewitness memory. British Journal of Psychology, 83, 323–36.

Gamst, K. T., & Langballe, Å. (2004). Barn som vitner: En empirisk og teoretisk studie av kommunikasjon mellom av avører og barn i dommeravhør: Utvikling av en avhørsmetodisk tilnærming. [Children who testify: An empirical and theoretical study of the communication between interviewer and child during forensic interviews: The development of an interviewing approach] (Doctoral dissertation). University of Oslo.

Gilstrap, L. L., & Ceci, S. J. (2005). Reconceptualizing children’s suggestibility: Bidirectional and temporal properties. Child Development, 76, 40–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00828.x.

Gjellan, M., & Hirsti, K. (2018, February 16). Overgrepssaker mot barn blir liggende i flere måneder uten etterforskning [Cases involving child abuse are delayed several months without an investigation]. NRK. Retrieved from https://www.nrk.no/norge/overgrepssaker-mot-barn-blir-liggende-i-flere-maneder-uten-etterforskning-1.13917781

Goodman, G. S., & Melinder, A. (2007). Child witness research and forensic interviews of young children: A review. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 12, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532506X156620.

Guadagno, B. L., & Powell, M. B. (2009). A qualitative examination of police officers' questioning of children about repeated events. Police Practice and Research, 10, 61–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614260802128468.

Hershkowitz, I., Horowitz, D., & Lamb, M. E. (2005). Trends in children’s disclosure of abuse in Israel: A national study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29, 1203–1214.

Hershkowitz, I., Lamb, M. E., & Katz, C. (2014). Allegation rates in forensic child abuse investigations: Comparing the revised and standard NICHD protocols. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 20(3), 336–344. https://doi.org/10.1037/a003739.

Hershkowitz, I., Lamb, M. E., Katz, C., & Malloy, L. C. (2015). Does enhanced rapport-building alter the dynamics of investigative interviews with suspected victims of intra-familial abuse? Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, 1, 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-013-9136-8.

Howe, M. L., & Knott, L. M. (2015). The fallibility of memory in judicial processes: Lessons from the past and their modern consequences. Memory, 23, 633–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2015.1010709.

Johnson, M., Magnussen, S., Thoresen, C., Lønnum, K., Burell, L. V., & Melinder, A. (2015). Best practice recommendations still fail to result in action: A national 10-year follow-up study of investigative interviews in CSA cases. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 29, 661–668. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3147.

Korkman, J., Santilla, P., & Sandnabba, N. K. (2006). Dynamics of verbal interaction between interviewer and child in interviews with alleged victims of child sexual abuse. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 47, 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2006.00498.x.

Lamb, M. E., Hershkowitz, I., Orbach, Y., & Esplin, P. W. (2008). Tell me what happened: Structured investigative interviews of child victims and witnesses. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

Lamb, M. E., Hershkowitz, I., Sternberg, K. J., Esplin, P. W., Hovav, M., Manor, T., & Yudilevitch, L. (1996). Effects of investigative utterance types on Israeli children’s responses. International Journal of Behavioural Development, 19, 627–637. https://doi.org/10.1177/016502549601900310.

Langballe, Å., & Davik, T. (2017). Sequential interviews with preschool children in Norwegian barnahus. In S. Johansson, K. Stefansen, E. Bakketeig, & A. Kaldal (Eds.), Collaborating against child abuse: Exploring the Nordic barnahus model (pp. 165–183). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

La Rooy, D., Katz, C., Malloy, L., & Lamb, M. (2010). Do we need to rethink guidance on repeated interviews? Psychology, Public Policy and Law, 16, 373–392. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019909.

Malloy, L. C., Orbach, Y., Lamb, M. E., & Graffam Walker, A. (2016). “How” and “why” prompts in forensic investigative interviews with preschool children. Applied Developmental Science, 1, 58–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2016.1158652.

Magnusson, M., Ernberg, E., Landström, S., & Akehurst, L. (2020). Forensic interviewers’ experiences of interviewing children of different ages. Psychology, Crime & Law, advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2020.1742343.

McWilliams, K., Stolzenberg, S. N., Williams, S., & Lyon, T. D. (2019). Increasing maltreated and non-maltreated children’s recall disclosures of a minor transgression: The effect of back-channel utterances, a promise to tell the truth and a post-recall putative confession. Child Abuse & Neglect. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104073.

Melinder, A., Alexander, K., Cho, Y., Goodman, G. S., Thorensen, C., Lønnum, K., & Magnussen, S. (2010). Children’s eyewitness memory: A comparison of two interviewing strategies as realized by forensic professionals. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 105, 156–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2009.04.004.

Melinder, A., & Gilstrap, L. L. (2009). The relationships between child and forensic interviewer behaviours and individual differences in interviews about a medical examination. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 6, 365–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405620701210445.

Melinder, A., Mirandola, C., & Gilstrap, L. (2020). Emotion: Internal and external consequences for legal authorities. In R. Bull & I. Blandon-Gitlin (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of legal and investigative psychology. London and New York: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group.

Poole, D. A. (2016). Interviewing children: The science of conversation in forensic contexts. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association.

Price, H. L., Roberts, K. P., & Collins, A. (2013). The quality of children’s allegations of abuse in investigative interviews containing practice narratives. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 2, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jarmac.2012.03.001.

Santtilla, P., Korkman, J., & Sandnabba, K. (2004). Effects of interview phase, repeated interviewing, presence of a support person, and anatomically detailed dolls on child sexual abuse interviews. Psychology, Crime & Law, 10, 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316021000044365.

Saywitz, K. J., & Camparo, L. B. (2014). Evidence-based child forensic interviewing: The developmental narrative elaboration interview. New York: Oxford University Press.

Saywitz, K. J., Larson, R. P., Hobbs, S. D., & Wells, C. R. (2015). Developing rapport with children in forensic interviews: Systematic review of experimental research. Behavioural Sciences and the Law, 33, 372–389. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2186.

Saywitz, K. J., Lyon, T. D., & Goodman, G. S. (2018). Interviewing children. In J. Conte & B. Klika (Eds.), APSAC Handbook on Child Maltreatment. (4th ed. pp-310-329). Newbury Park: Sage.

Sternberg, K. J., Lamb, M. E., Davies, G. M., & Westcott, H. L. (2001). The memorandum of good practice: Theory versus application. Child Abuse & Neglect, 25, 669–681. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0145-2134(01)00232-0.

U.S. Department of Justice. (2015). Child forensic interviewing: Best practices. Retrieved from https://www.ojjdp.gov/pubs/248749.pdf

Volbert, R., & Steller, M. (2014). Is this testimony truthful, fabricated, or based on false memory? Credibility assessment 25 years after Steller and Köhnken (1989). European Psychologist, 19, 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000200.

Walker, A. G. (2013). Handbook on questioning children: A linguistic perspective (3d ed.). Washington, DC: ABA Center on Children and the Law.

Wolfman, M., Brown, D., & Jose, P. (2016). Talking past each other: Interviewer and child verbal exchanges in forensic interviews. Law and Human Behavior, 40, 107–117. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000171.

Wolpe, S., & Goodman, G. S. (2019). (Eds.). Child witness research in a rights-conscious age. International Journal on Child Maltreatment, 2, 211–217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42448-019-00035-4.

Yoder, P. J., & Feurer, I. D. (2000). Quantifying the magnitude of sequential association between events or behaviours. In T. Thompson & D. Felce (Eds.), Behavioural observation: Technology and applications in developmental disabilities (pp. 317–333). Baltimore: Brookes Publishing.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Oslo (incl Oslo University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Melinder, A., Magnusson, M. & Gilstrap, L.L. What Is a Child-Appropriate Interview? Interaction Between Child Witnesses and Police Officers. Int. Journal on Child Malt. 3, 369–392 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42448-020-00052-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42448-020-00052-8