Abstract

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). Usually, it presents as expanding mass in the neck or abdomen but can present in unusual ways as an extranodal disease, with multiorgan involvement. Appropriate suspicion and workup can lead to early diagnosis to initiate early treatment, but it comes with multiple challenges, in case of older frail population. Herewith, we are reporting our patient, a 63-year-old frail older woman presented as multiple cranial nerve palsy and renal impairment at presentation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The most common type of non-Hodgkins lymphoma (NHL) is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) amounting to 30–40%, and the most common subtype is a non-specified variant approximating 80–85% [1]. However, the central nervous system (CNS) and renal involvement are rare at the time of diagnosis [2]. We report a high-grade lymphoma masquerading as multiple cranial palsies in a frail older woman and the diagnostic and treatment challenges involved.

Case Report

A 63-year-old female patient presented to us with the history of headache for 1 year, recurrent fever for 6 months, difficulty in swallowing with hoarseness of voice for 2 months, and nasal regurgitation and diplopia for 10 days. She had no prior hospital admissions or chronic medical conditions. At the time of admission, she was conscious and oriented, pallor was present, and her blood pressure was 152/100 mmHg. The rest of her general physical examination was normal. Her neurological examination revealed a normal higher mental function. Cranial nerve examination revealed papilledema; bilateral lateral rectus palsy; uvula deviated to the right; and absent gag reflex on the left side indicating involvement of II, VI, IX, and X cranial nerves. The rest of her motor and sensory examination was normal. Indirect laryngoscopy revealed left total vocal cord palsy.

Investigations

Her blood investigations showed, hemoglobin 7.9 g/dl (12–15 g/dl), TLC 9240 cells/cu. Mm (N 79.6%, L 10.6%, M 8.3%, E 1%, B 0.5%), platelets 5.92 lakhs/cu.mm, creatinine 4.9 mg/dl (0.5–1 mg/dl), calcium 10.3 mg/dl (8.50–10.50 mg/dl), potassium 5.1 mg/dl (3.5–5 mg/dl), and lytic lesions in the skeletal survey along with L3 and L5 vertebral collapse. Peripheral smear showed normocytic normochromic red blood cells with hyper segmented neutrophils. MRI of the brain (Fig. 1) revealed bilateral basal ganglia calcification, along with calcification in centrum semiovale, dentate nucleus, and cerebellar folia with multifocal calvarial destruction and subacute infarcts in right frontal, parietal lobes, and cerebellum. Her vitamin D3 and iPTH levels were 22.4 ng/ml (25–80 ng/dl) and 34.8 pg/ml (15–68.3 pg/ml) respectively. Ultrasonography abdomen revealed bilaterally enlarged kidneys with the mild hypoechoic cortex. Her serum ACE levels were 19 U/L, and the kappa/lambda ratio was 0.974. Abdominal fat pad biopsy showed no evidence of amyloid deposition on the special stain. Her CSF analysis showed 5 WBCs and 100% lymphocytes, with protein and glucose levels of 206 mg/dl and 41 mg/dl and negative for infectious diseases (gram stain and culture, fungal stain and culture, viral serology, and mycobacterial studies) and malignant cells.

Axial non-contrast CT at the level of kidneys showing bilaterally enlarged kidneys (left > right) (A); axial bone window of non-contrast CT of head showing multiple lytic lesions in the skull (B): Computer tomography of brain, bone window shows lytic lesions in the skull (BC); CT-guided biopsy being performed with the patient in the prone position. Axial image showing the tip of the needle within a lytic lesion in the sacrum (CD); T2-weighted MRI of the brain at the level of the lateral ventricles showing multiple patchy T2 hyperintense area involving both the gray and white matter in the right frontal lobe as well as multiple T2 hyperintense lesions in the skull. Control scans not performed in view deranged renal parameters

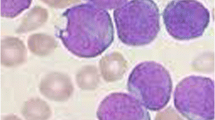

Renal biopsy revealed juxtamedullary invasion of large-sized atypical cells (Fig. 2), immunopositive for CD20 while negative for pan-cytokeratin and CD 3. Sacral biopsy showed large-size atypical lymphoid cells immune-positive for CD20 and Bcl2 (focal) while negative for CD3, CD10, Bcl 6, Tdt, and Cyclin d1. Ki 67 labelling index is approximately 50–60%. Overall features were suggestive of a high-grade B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). 18FDG PET-CT revealed metabolically active cutaneous lesions of the scalp, left anterior diaphragmatic lymph node, bilateral breast nodules, multiple skeletal sites, and bilateral kidneys. Coarse calcifications in the brain were with no significant tracer uptake.

A diagnosis of stage 4 NHL type (renal, breast, bone, brain) with CKD stage 5 was made.

Management

The patient was kept on Ryle’s tube feed due to dysphagia. Her creatinine clearance was 7 ml/min, and the body surface area (BSA) was 1.29 (Du Bois method). Her CARG (Cancer and Aging Research Group) score was 17, which indicated 95% at risk for chemotherapy toxicity. She was planned for reduced-dose polychemotherapy and given intrathecal methotrexate 4 mg according to her BSA, followed by rasburicase 6 mg (0.2 mg/kg) to prevent tumor lysis syndrome with proper hydration. It was followed by cyclophosphamide (750 mg/m2, 50% dose administered due to renal impairment). Rituximab 500 mg (375 mg/m2) and prednisolone 50 mg were also given; doxorubicin and vincristine were withheld due to pre-existing anemia, frailty, and poor general condition of the patient. The patient developed tumor lysis (calcium 7 mg/dl (8.50–10.50 mg/dl); potassium 7.5 mg/dl (3.5–5 mg/dl); uric acid 9 mg/dl; urine output 400 ml/day) on the second day of chemotherapy which was managed with one cycle of hemodialysis, hydration, and anti-hyperkalemic measures. The patient recovered from tumor lysis, but on day three, she had one episode of aspiration with falling saturation and required mechanical ventilation. She underwent tracheostomy and was on minimal respiratory support and planned for weaning. On day 5, she developed VAP along with severely suppressed bone marrow. She was given adequate anti-bacterial medicine with pseudomonal coverage and antifungal medicine along with two doses of filgrastim 6 mcg/kg/day. The patient condition worsened; she developed neutropenic sepsis along with bone marrow failure and succumbed to death during the hospital course.

Discussion

DLBCL is a B-cell neoplasm accounting for 30–40% all NHL. The incidence increases with age median being 7th decade with a male preponderance. About 40% of the patients have extranodal involvement, with the gastrointestinal tract being the most common site. Bone marrow involvement occurs in 10–20% of patients, and it indicates poor prognosis [1]. However, renal involvement at the time of diagnosis is rare (4%), and there are reports suggesting renal involvement and CNS involvement occur with a frequency of 44% and 7% respectively. These patients were predominantly females and had a median age of 58 years [2]. This can be differentiated from primary renal lymphoma characterized by (1) primary renal mass with lack of extrarenal lymphomatous involvement, (2) absent leukemic blood picture, and (3) lack of clinical and radiological evidence of hepatosplenomegaly and peripheral lymphadenopathy [3]. Clinical symptoms widely vary depending on organ involvement like gastrointestinal disease, bone or testes involvement, and occasionally as “B” symptoms like fever, night sweats, and weight loss. In the case of CNS involvement, namely leptomeningeal disease, the presentation will widely vary, not limiting to headache, paraplegia, and multiple cranial nerve palsies [4]. The optimal method of diagnosis is by surgical excision biopsy. CECT plays a limited role in case of renal involvement due to renal insufficiency, limited sensitivity (23–38%), and similar focal mimics like angiomyolipoma and RCC. MRI is the ideal modality of choice in patients who have the aforementioned limitations and have higher sensitivity (20 to 91%). The role of CSF is limited to flow cytometry and immunophenotyping if performed before MRI may lead to false-positive leptomeningeal enhancement. With the emergence of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), the role of bone marrow biopsy is limited in advanced stages, and also having superiority in demonstrating the hepatosplenic involvement [4,5,6]. The treatment in older patients cannot be generalized due to the presence of multiple co-morbidities, frailty, and poor functional status. ESMO (European Society of Medical Oncology) recommends R-CHOP (R, rituximab; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisone) in the fit older patients up to 80 years, and R-mini CHOP or substitution of doxorubicin by gemcitabine, etoposide, or liposomal doxorubicin, or even its omission in case of frail or unfit older patients more than 80 years [7]. Many trials involving DLBCL trials lacked enrolment of older patients and further assessments were complicated due to poor physical performance, poor nutritional status, and multiple co-morbidities. There were attempts to develop a simplified comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) and individualize the approach; still, trials with larger sample size are the need of the hour [6, 8,9,10].

Availability of Data and Material

Subject to the clearance by the institute ethics and research committee.

Code Availability

Not applicable

References

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma - Pathology. [cited 2019 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.pathologyjournal.rcpa.edu.au/article/S0031-3025(17)30471-3/fulltext.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with involvement of the kidney: outcome and risk of central nervous system relapse | Haematologica. [cited 2019 Aug 6]. Available from: http://www.haematologica.org/content/96/7/1002.short#ref-1.

Primary renal lymphoma - OMER - 2007 - Nephrology - Wiley Online Library. [cited 2019 Aug 6]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1440-1797.2007.00783.x.

Carcinomatous meningitis: leptomeningeal metastases in solid tumors. [cited 2019 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3656567/.

Imaging of primary and secondary renal lymphoma. Am J Roentgenol. 201(5) (AJR). [cited 2019 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.ajronline.org/doi/full/10.2214/AJR.13.10669.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL): ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up† | Annals of Oncology | Oxford Academic. [cited 2019 Aug 6]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/annonc/article/26/suppl_5/v116/345089#35546363.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines | ESMO. [cited 2020 Jan 25]. Available from: https://www.esmo.org/Guidelines/Haematological-Malignancies/Diffuse-Large-B-Cell-Lymphoma.

Management of aggressive lymphoma in very elderly patients. [cited 2019 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5873382/.

Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma in the Elderly: A Review of Potential Difficulties | Clinical Cancer Research. [cited 2019 Aug 6]. Available from: https://clincancerres.aacrjournals.org/content/19/7/1660#.

Tailored therapy in an unselected population of 91 elderly patients with DLBCL prospectively evaluated using a simplified CGA. [cited 2019 Aug 6]. Available from: http://theoncologist.alphamedpress.org/content/17/5/663.short.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Manuscript writing and interpretation of the data: Manicka Saravanan Subramanian and Abhijith Rajaram Rao. Acquisition and interpretation of the data: Urza Bhattarai, Naren Hemachandran, and Mohamad Sulaiman. Critical revision of the manuscript for intellectual content: Aparajit Ballav Dey.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All authors declare that this manuscript does not report on a clinical trial and the ethics committee approval is not required.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable

Consent for Publication

I confirm that the authors of the manuscript “Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma with Renal Involvement Presenting with Multiple Cranial Nerve Palsy in a Frail Older Adult: a Case Report” made every attempt to obtain written authorization, but the patient was deceased, and the authors were unable to contact any of the patient’s family members. This manuscript contains no patient identifiers and is anonymous. It is compliant with all institutional regulations.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Medicine

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Subramanian, M.S., Rao, A.R., Bhattarai, U. et al. Diffuse Large B-cell Lymphoma with Renal Involvement Presenting with Multiple Cranial Nerve Palsy in a Frail Older Adult: a Case Report. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 3, 1951–1954 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-021-00956-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42399-021-00956-7