Abstract

Purpose

Inappropriate use of diagnostic and therapeutic medical procedures is common and potentially harmful for older patients. The Austrian Society of Geriatrics and Gerontology defined a consensus of five recommendations to avoid overuse of medical interventions and to improve care of geriatric patients.

Methods

From an initial pool of 147 reliable recommendations, 20 were chosen by a structured selection process for inclusion in a Delphi process to define a list of five top recommendations for geriatric medicine. 12 experts in the field of geriatric medicine scored the recommendations in two Delphi rounds.

Results

The final five recommendations are concerning urinary catheters in elderly patients, percutaneous feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia, antipsychotics as the first choice to treat behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, and screening for breast, colorectal, prostate, or lung cancer, and the use of antimicrobials to treat asymptomatic bacteriuria.

Conclusions

The selected recommendations have the potential to improve medical care for older patients, to reduce side effects caused by unnecessary medical procedures, and to save costs in the health care system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Currently, Europe has the largest proportion of people in the age of 60 years and above in the world [1]. The oldest population group of people 80 years and older is expected to grow from 137 million in 2017 to 425 million in the year 2050 worldwide [1]. Higher age is a major risk factor for multiple morbidities and impaired functional capacities [2].

Health care systems, traditionally focussing on single disease management, have not yet fully adapted to the changing health care needs of an aging population presenting with multimorbidity and associated polypharmacy, geriatric syndromes, and reduced functional resilience [3,4,5,6]. Lack of coordination between attending physicians of different medical disciplines can result in the ineffective and inadequate treatment of multimorbid and frail persons [7]. Geriatric medicine, as a specialty of internal medicine, is not yet established in some European countries. Chronic care for older patients is in the hands of primary care physicians and other specialties not specifically trained for the distinct care needs of older patients. In several European countries, the undergraduate education and training in geriatric medicine has been reported as inadequate in various studies [8,9,10,11]. Efforts to include geriatric content in curricula for the training of medical doctors are ongoing across Europe. However, it will take years until changes in education and training will result in sustainable changes in daily practice focussed on older people.

One option to accelerate change towards better care for older patients is the introduction of practice guidelines into clinical work [12]. In 2012, the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation (ABIMF) launched an initiative called “Choosing Wisely” questioning the impact of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in certain clinical situations and with specific target groups. “Top five” lists of medical procedures performed too often and without supporting evidence in daily clinical practice were developed on evidence- and eminence-based criteria by medical specialty societies [13]. The ongoing Choosing Wisely initiative aims at fostering communication between patients and physicians about what is appropriate and beneficial treatment. Choosing Wisely has published about 500 recommendations regarding 75 medical specialty societies, including the American Geriatrics Society [14]. During the last few years, Choosing Wisely initiatives have been launched in several other countries [15]. It is the aim of the work presented in this publication to develop in a national Choosing Wisely initiative called “gemeinsam gut entscheiden” recommendations for the management of geriatric patients in Austria. Geriatric patients were defined according to the definition of the European Union of Medical Specialists [16].

Methods

Literature search

All published recommendations of the US Choosing Wisely initiative were identified through the website of the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation [17]. Additionally, a search for recommendations from Mid-European Choosing Wisely initiatives through the websites of the DianaHealth project of the Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Epidemiología y Salud Pública [18] and the Less is More project was performed [19]. The literature searches were performed in April 2017. Recommendations were judged to be trustworthy if they had equivalent recommendations in German S3-guidelines or if the development process was judged to be of high methodological quality and meta-literature supporting the recommendation was cited [20].

Selection of experts

Raters for the consensus process were selected according to clinical and academic expertise in the field of geriatric medicine. An attempt was made to collect the broadest possible range of national expert opinion. The core group included geriatricians with academic background and working in university setting, geriatricians with focus on clinical work in acute geriatric wards and in primary care as well as one clinical pharmacist working in an acute care hospital and dealing with older patients across various specialties in hospital. All of the experts who were invited were members of the academic or executive board and of expert groups of the Austrian Society of Geriatrics and Gerontology at the time of their invitation [21]. The experts were invited by e-mail and asked for their willingness to participate in the consensus process. All of the experts signed a conflict of interest form to substantiate their neutrality in evaluating the items.

The Delphi process

The Delphi technique is a well-established consensus-finding method that is used to determine the extent of agreement among panellists regarding a specific query [22,23,24]. The authors used a modified Delphi process with the aim of creating a top five list of tests and treatments that have little or no demonstrable benefit, or that can be harmful. The survey was conducted anonymously in German from November 2017 to January 2018 using the online survey platform Survey Monkey™. In the Delphi survey rounds, experts were asked to rate each item regarding its clinical relevance using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (less important) to 5 (very important). For each recommendation, a mean score of Likert scale assessments and standard deviations was calculated. All expert ratings from the first round of the Delphi survey were summarized and ranked by their mean score. The items were transcribed then into a new version of the template and all 20 items were sent out along with an overall result from the first round to all raters for a second evaluation. To assess the degree of consistency among the experts’ scores, an intra-class correlation coefficient based on a two-way random effect model using IBM SPSS ( International Business Machines Corporation—Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) was calculated.

Results

Selection of medical recommendations for the Delphi process

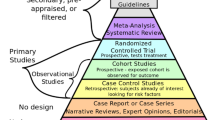

Figure 1 displays the process for selecting Choosing Wisely recommendations from those published in the scientific literature, and on authorized web-based platforms and homepages. 147 recommendations were identified by our initial literature search. We excluded 42 duplicates (identical recommendations from various medical specialist societies) and 21 recommendations with similar content. Another 18 recommendations were excluded as they were not relevant for older people: recommendations for children and adolescents (8 items), young women and pre-menopausal women (3 items), occupational medicine (5 items), and obstetrics (2 items). In addition, two recommendations without a specific target group were excluded, as in both cases, a special recommendation for older, geriatric people already existed. From the remaining pool of 64 items, a core study group selected the most relevant recommendations for avoiding unnecessary tests and therapy in daily clinical practice that should be considered for further evaluation. Finally, 20 trustworthy recommendations were available for the top five lists and for assessment by experts (Fig. 1). The 20 recommendations used in the primary template for the Delphi process are shown in Table 1.

First Delphi round

From the 15 experts in geriatric medicine who were invited to participate in the consensus-finding process, 12 experts responded and took part in the whole process. From the 20 recommendations presented in the first Delphi round, the following items received the highest mean scores: the overuse of urinary catheters in older patients, the percutaneous feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia, the use of antipsychotics as the first choice for treating the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, the screening for breast, colorectal, prostate, or lung cancer in people with limited life expectancy, and the use of antimicrobials to treat asymptomatic bacteriuria. The results of the first round of the Delphi process are shown in Table 2.

However, there was inconsistency in the ratings by the experts during the first Delphi round. While each of the five items with the highest mean value achieved scores of 4 or 5 with at least 75% of the raters, one item was rated with a score of 1 by one panel member and two items were given a score of 2 indicating the necessity for a second consensus round. The intra-class correlation coefficient of the ratings was 0.79, 95% CI 0.59–0.92.

Second Delphi round

All raters participating in round one also completed Delphi round two. In the second round, a consensus for the five most important recommendations could be defined (Table 3). The second Delphi round demonstrated an even broader agreement on the top five recommendations from round one with over 90 percent of the top five items from round one receiving scores of 4 or 5 (mean scores 4.5–4.8, standard deviation 0.4–0.7). The calculated intra-class correlation coefficient of the raters’ votes of Delphi round two was 0.73, 95% CI 0.52–0.89.

Discussion

Evaluations of care pathways for older patients in Austria recorded potentially harmful diagnostic and therapeutic procedures in geriatric patients without expected benefit or medical indication [25]. Therefore, national care providers and the Austrian Society of Geriatrics and Gerontology in collaboration with two public universities in Austria initiated the development of Choosing Wisely recommendations for the management of geriatric patients in Austria. These recommendations have become necessary in medicine as rapid advances in diagnostic and therapeutic options have increased not only the appropriate use of those options, but also their unnecessary and sometimes harmful use [26]. The Choosing Wisely initiative aims at promoting greater patient involvement in the decision-making and treatment planning process. In other countries also, several similar campaigns have started with the same purpose [27,28,29]. However, Choosing Wisely top five lists may be confronted with criticism for lacking strict methodological requirements in the process of their development [30]. This uncertainty about evidence has an impact on their acceptance and application by physicians, and uncertain evidence of recommendations can possibly lead to harm for patients. For this reason, various expert groups have developed top five lists on the basis of solid scientific evidence and well-defined selection processes [31, 32]. For the development of the Austrian top five lists for geriatric medicine as presented here, only recommendations that fulfilled the methodological quality criteria of German S3 guidelines and guidelines based on a methodologically well-performed development process were included [20]. This strengthens the trustworthiness and the safety of these recommendations.

Compared to recommendations already existing to avoid medical overuse in the management of geriatric patients from the US [33], Canada [34], and Australia [35], the Austrian recommendations are in line with the major international topics in geriatric care. Interestingly, Austrian geriatricians see a strong demand to avoid overuse of urinary catheter placements in geriatric patients. Recently, Rossi and colleagues could show in an Italian cohort of 427 older in-hospital patients that the placement of urinary catheters was a predictor of intercurrent clinical events, such as delirium and infections, and therefore, prolonged hospital stays and worsened clinical outcomes [36]. The ESAMED study group found similar data, demonstrating an additional functional decline following hospital stays in patients unnecessarily treated with urinary catheters [37].

Recommendation number five from the Austrian “gemeinsam gut entscheiden” list for geriatric patients differs from all of the other published recommendations and addresses the overuse of diagnostic procedures to detect malignancies in the elderly population on a routine basis. There is currently no evidence in the literature that cancer screening programs are effective and efficient in the care of geriatric patients. In Austria, the national health care system provides access to such diagnostic procedures up to an advanced age without cost to the patient. The panel members of the “gemeinsam gut entscheiden” committee found this issue to be so significant and common in the care of older people in Austria that they included this recommendation in the top five lists. Obviously, due to different health care systems, this recommendation is not listed as a priority in other lists of Choosing Wisely initiatives for geriatric patients. This fact underlines the importance of developing national recommendations for certain patient groups. Patients with complex care needs are major consumers in health care systems and account for a high percentage of the costs in the health systems. Integration of care pathways for those clients has become a priority for many health care systems [38]. A shared guide for standards of practice will be useful in the treatment of geriatric patients when “traditional” guidelines fail to address their complex needs. This is the first step towards a common effort to drive health care systems towards integrated care at least for geriatric patients [39]. Especially in those countries where geriatric medicine is not yet established as a medical specialty, recommendations of Choosing Wisely initiatives may help to raise awareness regarding the complexity of care for geriatric patients in daily clinical work.

Finally, it will be important to inform a broad public audience and to enhance older people’s and patients’ acceptance of the recommendations. As shown in the literature, physicians’ perceptions of the unacceptability for patients of applying Choosing Wisely recommendations appear to be a major barrier towards implementation [40]. Geriatricians will have to share their professional expertise with other physicians to modify their practice styles and to inform patients in a shared decision-making process to support patients and to avoid unnecessary and possibly harmful medical procedures. It may also be argued that the lack of indicators measuring the impact of recommendations on quality of care is a major drawback of the work presented, but there are already data in the literature that addresses this issue. Colleagues from the Harvard Medical School, Department of Health Care Policy, have tried to address this challenge creating 26 indicators, clustered in 6 categories, to determine low value services for patients in the surgical care setting using Choosing Wisely criteria. Implementing those indicators and aligning outcomes with costs, they found that the recommendations affected only a modest percentage of the expenses, while affecting a substantial proportion of care beneficiaries [41]. So far, comparable data for the effects of Choosing Wisely recommendations in the geriatric care management are missing in literature.

It can be concluded that the recommendations from the list of the Austrian Choosing Wisely initiative “gemeinsam gut entscheiden” have the potential to improve medical care for older patients and to reduce side effects caused by unnecessary medical procedures. In addition, the application of these guidelines can save costs in the health care system, which has not been evaluated in studies up until now. Future studies should focus on the economic effects of Choosing Wisely initiatives.

References

United Nations (2017) World population prospects. The 2017 revision. United Nations, New York

Boyd CM, Fortin M (2010) Future of multimorbidity research: how should understanding of multimorbidity inform health system design? Public Health Rev 32:451–474

Marengoni A, Angleman S, Melis R, Mangialasche F, Karp A, Garmen A, Meinow B, Fratiglioni F (2011) Aging with multimorbidity: a systematic review of the literature. Ageing Res Rev 10:430–439

American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity (2012) Guiding principles for the care of older adults with multimorbidity: an approach for clinicians. J Am Geriatr Soc 60:1–25

American Geriatrics Society Expert Panel on the Care of Older Adults with Multimorbidity (2012) Patient-centered care for older adults with multiple chronic conditions: a stepwise approach from the American geriatrics society. J Am Geriatr Soc 60:1957–1968

World Health Organization. World report on ageing and health. 2015. http://www.who.int/ageing/events/world-report-2015-launch/en/. Accessed 10 May 2018

Rechel B, Grundy E, Robine JM, Cylus J, Mackenbach JP, Knai C, McKee M (2013) Ageing in the European Union. Lancet 381:1312–1322

Michel JP, Huber P, Cruz-Jentoft AJ (2008) Europe-wide survey of teaching in geriatric medicine. J Am Geriatr Soc 56:1536–1542

Gordon AL, Blundell AG, Gladman JR, Masud T (2010) Are we teaching our students what they need to know about ageing? Results from the UK National Survey of Undergraduate Teaching in Ageing and Geriatric Medicine. Age Ageing 39:385–388

Singler K, Sieber CC, Biber R, Roller RE (2013) Considerations for the development of an undergraduate curriculum in geriatric medicine. Gerontology 59:385–391

Singler K, Holm EA, Jackson T, Robertson G, Müller-Eggenberger E, Roller RE (2015) European postgraduate training in geriatric medicine: data of a systematic international survey. Aging Clin Exp Res 27:741–750

Kredo T, Bernhardsson S, Machingaidze S, Young T, Louw Q, Ochodo E, Grimmer K (2016) Guide to clinical practice guidelines: the current state of play. Int J Qual Health Care 28:122–128

Wolfson D, Santa J, Slass L (2014) Engaging physicians and consumers in conversations about treatment overuse and waste: a short history of the choosing wisely campaign. Acad Med 89:990–995

American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. Choosing Wisely. Facts and figures. 2018. http://www.choosingwisely.org/our-mission/facts-and-figures. Accessed 8 Apr 2018

Levinson W, Born K, Wolfson D (2018) Choosing wisely campaigns: a work in progress. JAMA. 319(19):1975–1976. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.2202

European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS) (2008) Geriatrics Section. Definition of geriatrics. http://uemsgeriatricmedicine.org/www/land/definition/english.asp. Accessed 25 Aug 2018

American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation (2017) Choosing Wisely. Promoting conversations between patients and clinicians. http://www.choosingwisely.org. Accessed 8 Apr 2017

Clinical Epidemiology Program of the Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red de Epidemiología y Salud Pública (2017) DianaHealth—dissemination of initiatives to analyse appropriateness in Healthcare. http://dianasalud.com/index.php. Accessed 8 Apr 2017

Otte J (2017) Less is more medicine: projects & initiatives. http://www.lessismoremedicine.com/projects/. Accessed 8 Apr 2017

Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften (2017). http://www.awmf.org/leitlinien/awmf-regelwerk/ll-entwicklung/awmf-regelwerk-01-planung-und-organisation/po-stufenklassifikation/klassifikation-s3.html. Accessed 8 Apr 2017

Österreichische Gesellschaft für Geriatrie und Gerontologie (2018). https://www.geriatrie-online.at/gesellschaft/vorstand/. Accessed 8 May 2018

Hsu CC, Sandford BA (2007) The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Practical Assessment Research and Evaluation. http://pareonline.net/pdf/v12n10.pdf. Accessed 4 Apr 2018

Preston CC, Colman AM (2000) Optimal number of response categories in rating scales: reliability, validity, discriminating power, and respondent preferences. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 104:1–15

Vernon W (2009) The Delphi technique: a review. Int J Ther Rehabil 16:69–76

Gogol M, Siebenhofer A (2016) Choosing Wisely – Gegen Überversorgung im Gesundheitswesen – Aktivitäten aus Deutschland und Österreich am Beispiel der Geriatrie. Wien Med Wochenschr 166:155–160

American Geriatrics Society Choosing Wisely Workgroup (2013) American Geriatrics Society identifies five things that healthcare providers and patients should question. J Am Geriatr Soc 61:622–631

Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften e.V. (AWMF) (2016) Gemeinsam Klug Entscheiden. http://www.awmf.org/medizin-versorgung/gemeinsam-klug-entscheiden.html. Accessed 4 Apr 2018

Malhotra A, Maughan D, Ansell J, Lehman R, Henderson A, Gray M, Stephenson T, Bailey S (2015) Choosing Wisely in the UK: the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges’ initiative to reduce the harms of too much medicine. BMJ 350:h2308

Levinson W, Kallewaard M, Bhatia RS, Wolfson D, Shortt S, Kerr EA (2015) “Choosing Wisely”: a growing international campaign. BMJ Qual Saf 24:167–174

Strech D, Follmann M, Klemperer D, Lelgemann M, Ollenschläger G, Raspe H, Nothacker M (2014) When Choosing Wisely meets clinical practice guidelines. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 108:601–603

McMahon LF Jr, Beyth RJ, Burger A, Chopra V, Feldstein D, Korenstein D, Subramanian U, Sussman J, Petty B, Tice J (2014) Enhancing patient-centered care: SGIM and choosing wisely. J Gen Intern Med 29:432–433

Schuur JD, Carney DP, Lyn ET, Raja AS, Michael JA, Ross NG, Venkatesh AK (2014) A top-five list for emergency medicine: a pilot project to improve the value of emergency care. JAMA Intern Med 174:509–515

American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation (2018) Recommendations of American Geriatrics Society. http://www.choosingwisely.org/clinicianlists/#keyword=geriatric&parentSociety=American_Geriatrics_Society. Accessed 12 May 2018

Choosing Wisely Canada (2018) Geriatrics. Five things physicians and patients should question. https://choosingwiselycanada.org/geriatrics/. Accessed 12 May 2018

Choosing Wisely Australia (2018) Australian and New Zealand Society for Geriatric Medicine: tests, treatments and procedures clinicians and consumers should question. http://www.choosingwisely.org.au/recommendations/anzsgm. Accessed 12 May 2018

Rossi PD, Bilotta C, Consonni D, Nobili A, Damanti S, Marcucci M, Mannucci PM, Mari D, REPOSI Investigators (2016) Predictors of clinical events occurring during hospital stay among elderly patients admitted to medical wards in Italy. Eur J Intern Med 32:38–42

Palese A, Gonella S, Moreale R, Guarnier A, Barelli P, Zambiasi P, Allegrini E, Bazoli L, Casson P, Marin M, Padovan M, Picogna M, Taddia P, Salmaso D, Chiari P, Frison T, Marognolli O, Benaglio C, Canzan F, Ambrosi E, Saiani L, ESAMED Group (2016) Hospital-acquired functional decline in older patients cared for in acute medical wards and predictors: findings from a multicentre longitudinal study. Geriatr Nurs 37:192–199

Bhattacharyya O, Schull M, Shojania K, Stergiopoulos V, Naglie G, Webster F, Brandao R, Mohammed T, Christian J, Hawker G, Wilson L, Levinson W (2016) Building bridges to integrate care (BRIDGES): incubating health service innovation across the continuum of care for patients with multiple chronic conditions. Healthc Q 19:60–66

Briggs AM, Valentijn PP, Thiyagarajan JA, Araujo de Carvalho I (2018) Elements of integrated care approaches for older people: a review of reviews. BMJ Open 8:e021194

Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Kullgren JT, Fagerlin A, Klamerus ML, Bernstein SJ, Kerr EA (2017) Perceived barriers to implementing individual Choosing Wisely® recommendations in two national surveys of primary care providers. J Gen Intern Med 32:210–217

Schwartz AL, Landon BE, Elshaug AG, Chernew ME, McWilliams JM (2014) Measuring low-value care in Medicare. JAMA Intern Med 174:1067–1076

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Medical University of Graz.

Funding

The work was supported by a restricted grant from the Main Association of Austrian Social Security Institutions (Hauptverband der Österreichischen Sozialversicherungsträger) and the Department of Health and Welfare of the province of Styria (Steirischer Gesundheitsfond) for administration of the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

The local ethics committee at Medical University of Graz stated that this study does not need any approval as no personal data are required.

Informed consent

For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Schippinger, W., Glechner, A., Horvath, K. et al. Optimizing medical care for geriatric patients in Austria: defining a top five list of “Choosing Wisely” recommendations using the Delphi technique. Eur Geriatr Med 9, 783–793 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-018-0105-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-018-0105-8