Abstract

Marriage patterns of immigrants can serve as an indicator of the degree of immigrant integration into their host countries. Literature on the economics of the household has focused on the role of the sex-ratio as an important determining factor in marriage market outcomes. Therefore, it is important to understand if and how the sex-ratio has changed over time and the mechanisms that may drive that change. In this paper, we explore recent changes in the sex-ratio among immigrants to the USA, focusing on the 24 highest sending countries of immigrants. First, building upon previous research, we document the non-gender-neutral nature of declining immigration to the USA. We approach this study from two different dimensions to document some of the forces driving this change in the sex-ratio. The first approach, focusing on changes between birth cohorts, demonstrates that immigration is declining more quickly for men than it is for women, leading to a decrease in the sex-ratio from above 100 and thus bringing about more gender-balanced migration. Second, we present results from an analysis of data on recently granted green cards, which suggests that the sex-ratio among this population is increasing from below 100, also bringing about more gender balance among immigrants. The period of study allows us to capture changes taking place pre- and post-Great Recession. We find declines in migration for both men and women during the Great Recession, but sharper recovery for women. Additionally, while migration has declined for both men and women in traditional receiving states, the stock of women has increased in non-traditional immigrant-receiving states.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We thank an anonymous referee for the suggestion to explore heterogeneity in our results in this dimension.

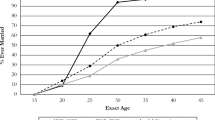

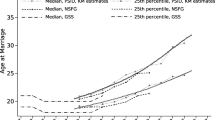

We find negative age gaps for only 26.13% of men and positive age gaps for only 9.99% of women. Men are married to women their own age, 1, 2, and 3 years older to themselves at rates of 12.65%, 12.40%, 11.39%, and 9.72%, respectively. For women, these figures are 10.56%, 10.74%, 10.38%, and 9.49%. A histogram displaying these results is presented in the Appendix in Fig. 10.

We do show that we can reject a null hypothesis of a constant sex-ratio at the 10% level for 1- or 2-year lags in our preferred specification in Appendix Table 5, where instead of using a linear time trend for birth cohorts we instead run a regression with birth cohort indicator variables and present the p values on an F test of joint significance of these parameters.

With the weighted regression, we show that we can reject a null hypothesis of a constant sex-ratio at the 1% level from zero up to three lags in Appendix Table 6.

As before, we also examine changes at the state level. In Appendix Tables 7 through 10, we repeat our analysis at the state level. Tables 7 and 8 show that the expected pattern of a decline in the sex-ratio among similarly aged immigrants, coupled with an increase in the sex-ratio for large age gaps between men and women is not found in the average marriage market, but is found for the average immigrant when using variation at the state level. Tables 9 and 10 demonstrate that there is strong evidence for a changing sex-ratio in both the weighted and unweighted regressions, at least when focusing on sex ratios with zero, 1 or 2 years of lags.

Prior data, such as the 1990 census, only provided an intervaled variable for arrival in the USA (e.g. 1980–1982. However, all data we employ here provides the exact year of arrival.

Details of each estimation are presented in Appendix Figs. 11 through 13. Together, the three figures present results from an analysis conducted separately for each of the 24 countries that we examine. Cell sizes here are of course even smaller than in the above analysis, so we expect that there may be some large outliers, especially for the later cohorts. A note at the bottom of the figure for each country also reports a p value on an F test of equality in the birth year indicator variables. We observe that there has been significant variation at the 5% level in the sex-ratio between birth cohorts using our more reliable weighted regressions for 13 of the 24 countries that we examine: Mexico, Honduras, Cuba, Germany, Russia, Japan, China, Taiwan, Korea, Laos, the Philippines, Vietnam and India. In addition, we also reject our null at the 10% but not 5% level for Haiti and El Salvador.

References

Amuedo-Dorantes, C, Grossbard S. Cohort-level sex ratio effects on women’s labor force participation. Rev Econ Househ 2007;5(3):249–78.

Angrist, J. How do sex ratios affect marriage and labor markets? Evidence from America’s second generation. Q J Econ 2002;117(3):997–1038.

Borjas, GJ. Assimilation, changes in cohort quality, and the earnings of immigrants. J Labor Econ 1985;3(4): 463–89.

Borjas, GJ. Heaven’s door, 2nd edn. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1999.

Card, D, Lewis E. The diffusion of Mexican immigrants in the 1990s: patterns and impacts. In: Borjas, GJ. Mexican immigration to the United States: University of Chicago Press 2007, pp. 193–228.

Çelikaksoy, A, Lena N, Rashid S. Assortative mating by ethnic background and education among individuals with an immigrant background in Sweden. ZfF–Zeitschrift für Familienforschung/J Fam Res. 2010;22(1).

Chi, M. Does intermarriage promote economic assimilation among immigrants in the United States? Int J Manpower 2015;36(7):1034–57.

Chi, M, Drewianka S. How much is a green card worth? Evidence from Mexican men who marry women born in the US. Labour Econ 2014;31:103–16.

del Rey Poveda, A, Vono de Vilhena D. Marrying after arriving: the role of individuals’ networks for immigrant choice of partner’s origin. Adv Life Course Res 2014;19:28–39.

Donato, KM, Bankston CL III. The origins of employer demand for immigrants in a new destination: the salience of soft skills in a volatile economy. In: Massey, DS. New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration: Russell Sage Foundation; 2008.

Donato, KM, Alexander JT, Gabaccia DR, Leinonen J. Variations in the gender composition of immigrant populations: how they matter. Int Migr Rev 2011;45(3):495–526.

Fennelly, K. Prejudice Toward Immigrants in the Midwest. In: Massey, DS. New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration: Russell Sage Foundation; 2008.

Furtado, D, Theodoropoulos N. Why does intermarriage increase immigrant employment? The role of networks. BE J Econ Anal Policy. 2010;10(1).

Furtado, D, Theodoropoulos N. Interethnic marriage: a choice between ethnic and educational similarities. J Popul Econ 2011;24(4):1257–79.

Furtado, D, Trejo SJ. 15 Interethnic marriages and their economic effects. In: Constant, AF, Zimmermann, KF. International handbook on the economics of migration: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2013, pp. 276–292.

Gevrek, Z E, Gevrek D, Gupta S. Culture, intermarriage, and immigrant women’s labor supply. Int Migr 2013;51(6):146–67.

Griffith, D. New Midwesterners, New Southerners: Immigration Experiences in Four Rural American Settings. In: Massey, DS. New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration: Russell Sage Foundation; 2008.

Grossbard, S. The marriage motive: a price theory of marriage: How marriage markets affect employment, consumption, and savings. Berlin: Springer; 2015.

Grossbard-Shechtman, S. On the economics of marriage: a theory of marriage labor and divorce. Boulder: Oxford England Westview Press; 1993.

Grossbard-Shechtman, S. The economics of marriage and household formation. In: Michael JB, Michelle ES, editors. Marriage and the economy: theory and evidence from advanced industrial societies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

Hanson, GH, McIntosh C. The great Mexican emigration. Rev Econ Stat 2010;92(4):798–810.

Hanson, G, Liu C, McIntosh C. 2017. Along the watchtower: the rise and fall of US low-skilled immigration. Brookings Panel on Economic Activity.

Hofmann, ET, Reiter EM. Geographic variation in sex ratios of the us immigrant population: identifying sources of difference. Popul Res Policy Rev 2018;37(3):485–509.

Jacobsen, R, Møller H, Mouritsen A. Natural variation in the human sex ratio. Hum Reprod 1999;14 (12):3120–5.

Marrow, HB. Hispanic immigration, Black population size and intergroup relations in the rural small-town south. In: Massey, DS. New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration: Russell Sage Foundation; 2008.

Massey, DS, Hirschman C. People and places: the New American Mosaic. In: Massey, DS. New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration: Russell Sage Foundation; 2008.

Massey, DS, Durand J, Pren KA. Explaining undocumented migration to the US. Int Migr Rev 2014;48 (4):1028–61.

Meng, X, Gregory RG. Intermarriage and the economic assimilation of immigrants. J Labor Econ 2005;23 (1):135–74.

Norlander, P, Sorensen TA. 21st Century Slowdown: The Historic Nature of Recent Declines in the Growth of the Immigrant Population in the United States. Migr Lett 2018;15(3):409–22.

Passel, JS, D’Vera C, Gonzalez-Barrera A. 2013. Population decline of unauthorized immigrants stalls, may have reversed. Pew Hispanic Center.

Portes, A, Rumbaut RG. Immigrant America. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1996.

Ruggles, S, Genadek K, Goeken R, Grover J, Sobek M, Grover J, Sobek M. 2017. Integrated public use microdata series: Version 7.0 [dataset].

SEC. US Dep’t of Homeland, Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. 2002–2016.

Villarreal, A. Explaining the decline in Mexico-U.S. Migration: the effect of the great recession. Demography 2014; 51(6):2203– 28.

Winders, J. Nashville’s New “Sodino”: Latino migration and the changing politics of race. In: Massey, DS. New faces in new places: the changing geography of American immigration: Russell Sage Foundation; 2008.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for feedback received from presentations of this paper at the 2nd annual Society of Economics of the Household meetings in Paris in May of 2018, as well as from a seminar presentation at the Warsaw School of Economics in June of 2018. We also thank Sankar Mukhopadhyay and Mark Nichols for their helpful cosmments. Todd Sørensen also thanks the Warsaw School of Economics for providing housing for a research visit, during which the initial draft of this paper was written.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix: Tables

Appendix: Figures

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Castañeda, A.H., Sørensen, T.A. Changing Sex-Ratios Among Immigrant Communities in the USA. J Econ Race Policy 2, 20–42 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41996-018-0025-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41996-018-0025-5