Abstract

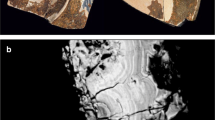

A lead-glazed porcelain teapot with an aluminous-silicic body recovered from an 18th-century privy in Philadelphia developed a partly crystallized (alkali feldspar) integrated body-glaze layer (IBGL) during kiln firing. Experiments on compositional analogs of the teapot show that a mineralogically and microstructurally similar ware can be created by firing for 48 hours at a peak kiln temperature of 1370oC. An IBGL, also with alkali feldspars, formed between the glaze and its ceramic substrate during >5 hours firing at 1000oC. The IBGL formed as alkalis and lead fluxed the substrate. These results confirm that very high temperatures were required to vitrify aluminous-silicic (“true” or “hard paste”) porcelain pastes, and indicate that heat was not invariably dumped from the glost kiln as soon as lead-rich glazes melted. Although relatively aluminous, the uptake of alumina by the glaze was less than that shown by lead-rich glazes on phosphatic porcelain fired at lower temperatures (~1250oC), evidently because this component is largely sequestered in a relatively refractory mineral (mullite) in true porcelain.

Abstracto

Una tetera de porcelana esmaltada con plomo y con cuerpo de silicio aluminoso recuperada de un retrete del siglo XVIII, en Filadelfia, desarrolló una capa integral de esmalte corporal (IBGL por sus siglas en inglés) (feldespato alcalino) parcialmente cristalizada durante el horneado. Los experimentos con análogos de composición de la tetera muestran que se puede crear una cerámica mineralógica y microestructuralmente similar horneando durante 48 horas (h) a una temperatura de horno máxima (T) de 1370°C. Se formó una capa IBGL, también con feldespatos alcalinos, entre el esmalte y su sustrato cerámico durante un horneado de >5 h a 1000°C. La capa IBGL se formó como álcalis y el plomo actuó como fundente del sustrato. Estos resultados confirman que para esmaltar las pastas de porcelana aluminosa-silícica ("verdadera" o "pasta dura") se requerían temperaturas muy altas, e indican que el calor no siempre se redujo rápidamente en el horno glost tan pronto como se fundieron los esmaltes ricos en plomo. Aunque relativamente aluminoso, la absorción de alúmina por el esmalte fue menor que la mostrada por esmaltes ricos en plomo en porcelana fosfática horneada a una T menor (~1250°C), evidentemente porque en porcelana verdadera este componente es secuestrado en gran parte en un mineral relativamente refractario (mullita).

Résumé

Une théière en porcelaine à glaçure plombifère avec corps alumineux siliceux provenant de toilettes du 18e siècle de Philadelphie a développé une couche de glaçure intégrée (integrated body-glaze layer ou IBGL en anglais) partiellement cristallisée (feldspath alcalin) durant sa cuisson au four. Des expériences menées sur des répliques compositionnelles de la théière démontrent qu’un article similaire aux points de vue minéralogique et microstructurel peut être créé à une température de pointe de 1 370 °C après 48 heures (h) de cuisson. Une IBGL, comportant aussi des feldspaths alcalins, s’est formée entre la glaçure et son substrat céramique durant >5 h de cuisson à 1 000 °C. L’IBLG s’est formée en tant qu’alcalis et le plomb a fluxé le substrat. Ces résultats confirment que des températures très élevées étaient requises pour vitrifier les pâtes de porcelaine alumineuse siliceuse (« dures » ou « pâtes dures »), et indiquent que la chaleur n’était pas invariablement évacuée du four de deuxième cuisson dès que les glaçures riches en plomb fondaient. Quoique relativement alumineuse, l’absorption d’oxyde d’aluminium par la glaçure était inférieure à celle notée pour les glaçures riches en plomb appliquées sur de la porcelaine phosphatée cuite à des températures inférieures (~1 250 °C), évidemment puisque cet élément est largement séquestré dans un minerai relativement réfractaire (mullite) à l’intérieur de la porcelaine dure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

All major element cation oxide data are reported as weight percent.

References

Hamer, Frank, and Janet Hamer 1997 The Potter’s Dictionary of Materials and Techniques, 4th edition. A&C Black, London.

Hunter, Robert, and Juliette Gerhardt 2016 An Eighteenth-Century American True-Porcelain Punch Bowl. In Ceramics in America 2016, Robert Hunter, editor, pp. 179–199. Chipstone Foundation, Milwaukee, WI.

Hunter, Robert, J. Victor Owen, Deborah Miller, John D. Greenough, and Brandon Boucher 2018 In Plain Sight: Rewriting Philadelphia’s 18th Century Porcelain History. In Ceramics in America 2018 (forthcoming), Robert Hunter, editor. Chipstone Foundation, Milwaukee, WI.

McBirney, Alexander R. 1985 Igneous Petrology. McGraw Hill, New York.

Owen, J. Victor 2002 Antique Porcelain 101: A Primer on the Chemical Analysis and Interpretation of Eighteenth-Century British Wares. In Ceramics in America 2002, Robert Hunter, editor, pp. 39–61. Chipstone Foundation, Milwaukee, WI.

Owen, J. Victor, and Jacob J. Hanley 2017 Bartlam Porcelain Re-created. American Ceramic Circle Journal 19:67–95.

Owen, J. Victor, Joe Petrus, and Xiang Yang 2016 Bonnin and Morris Revisited: The Geochemistry of a True-Porcelain Punch Bowl Excavated in Philadelphia. In Ceramics in America 2016, Robert Hunter, editor, pp. 200–219. Chipstone Foundation, Milwaukee, WI.

Ramsay, William R. H., and Elizabeth G. Ramsay 2008 A Case for the Production of the Earliest Commercial Hard-Paste Porcelains in the English-Speaking World by Edward Heylyn and Thomas Frye in about 1743. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Victoria 120(1):236–256.

Yamin, Rebecca, Alexander B. Bartlett, Tod L. Benedict, Kevin C. Bradley, Juliette Gerhardt, Timothy Mancl, Claudia L. Milne, Meagan Ratini, Leslie E. Raymer, and Kathryn Wood 2016 Archeology of the City—The Museum of the American Revolution Site. Archeological Data Recovery, Third and Chestnut Streets, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (Volume 1). Report to the Museum of the American Revolution, Philadelphia, from the Commonwealth Heritage Group, Inc., West Chester, PA.

Zumbulyadis, Nicholas 2010 Boettger’s Eureka! New Insights into the European Rediscovery of Porcelain. Bulletin of Historical Chemistry 35(1):24–32.

Acknowledgments:

A piece of teapot V.213 was made available courtesy of the Museum of the American Revolution. We thank Rod Jellicoe for his comments concerning the similarity of the teapot with Liverpool examples. We also thank Randolph Corney for preparing at short notice the carbon coated polished slides of our samples, and for drafting services. Xiang Yang ensured that the SEM ran smoothly. This paper was supported by funds made available by the Chipstone Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Owen, E.M., Owen, J.V., Hanley, J.J. et al. Development of an Integrated Body-Glaze Layer on an 18th-Century Lead-Glazed True Porcelain Teapot from Philadelphia: Insights from Kiln Firing Experiments on Compositional Analogs. Hist Arch 52, 617–626 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41636-018-0118-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41636-018-0118-7