Abstract

I review Lorentzian causality theory paying particular attention to the optimality and generality of the presented results. I include complete proofs of some foundational results that are otherwise difficult to find in the literature (e.g. equivalence of some Lorentzian length definitions, upper semi-continuity of the length functional, corner regularization, etc.). The paper is almost self-contained thanks to a systematic logical exposition of the many different topics that compose the theory. It contains new results on classical concepts such as maximizing curves, achronal sets, edges, horismos, domains of dependence, Lorentzian distance. The treatment of causally pathological spacetimes requires the development of some new versatile causality notions, among which I found particularly convenient to introduce: biviability, chronal equivalence, araying sets, and causal versions of horismos and trapped sets. Their usefulness becomes apparent in the treatment of the classical singularity theorems, which is here considerably expanded in the exploration of some variations and alternatives.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Let us consider a differentiable manifold M and a convex sharp cone distribution \(x\rightarrow C_x\subset T_xM\backslash 0\). Causality theory is the study of the global qualitative properties of the differential inclusion

where \(x\rightarrow C_x\) is upper semi-continuous and x(t) is absolutely continuous. This rather abstract point of view does a good job in mathematically framing Causality Theory but provides little insights on the motivations that brought researchers from mathematical relativity to its study.

Causality theory really developed within general relativity. Here the spacetime is a time oriented Lorentzian manifold (M, g), with g a metric of Lorentzian signature, i.e. \((-,+,\ldots , +)\). The cone \(C_x\) is then the future causal cone, namely a connected component of the double cone \(\{y\in T_xM\backslash 0:g(y,y)\le 0\}\) and so it is really round (it has ellipsoidal section). In general relativity g is usually assumed to be \(C^2\) in such a way that the Riemannian curvature is continuous. Often, depending on the application, stronger assumptions are contemplated. Since this work aims to introduce causality theory to the reader interested in general relativity we shall stick to the \(C^2\) Lorentzian metric case in the whole work.

1.1 History and peculiarities of causality theory

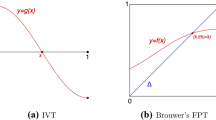

We can identify the birth of Lorentzian causality theory with the publication of the paper “Conformal treatment of null infinity” by Penrose (1964) and most notably with his landmark paper “Gravitational collapse and space-time singularities” (Penrose 1965a) (see also the review by Senovilla and Garfinkle 2015). In it Penrose employed global methods from differential geometry to predict the formation of singularities in the universe. Relevant but less geometrical ideas were contained in previous work by Raychaudhuri (1955). In short Penrose showed that if the geometry of spacetime is so bent that lightlike geodesics issued normally from a closed codimension two surface converge, then the spacetime develops a future geodesic singularity. Such special surfaces were termed trapped by Penrose.

In Penrose’s theorem there appeared many ingredients that today are recognized as characteristics of causality arguments entering singularity theorems (Senovilla 1998): an energy condition (the null convergence condition); a causality condition (global hyperbolicity); some special (hyper)surface which is believed to form under sufficient concentration of mass-energy (trapped surface).

Hawking soon realized that the approach could be adapted to study the singularities of the Universe as a whole, by replacing the trapped surface with a Cauchy hypersurface with diverging normal vector field (Hawking 1966b). This condition of expansion of the universe was indeed justified by the observed validity of the local Hubble law. His theorem predicted that under suitable energy conditions there had to be an initial singularity at the beginning of the Universe. The result caused a sensation in the public and in the subsequent years mathematical relativity began to develop at a fast pace. This early development is associated to the names of Penrose, Hawking, Geroch and Tipler. Within few years most relevant concepts, from global hyperbolicity to conformal completions, were identified and in fact, after only seven years from Penrose’s theorem, Penrose’s book (Penrose 1972; Lerner 1972) and the classic book by Hawking and Ellis (1973) signaled that mathematical relativity had transitioned to a mature theory.

It must be said that most of the community of theoretical physicists looked at these developments with interest but a bit from a distance. The tools from global differential geometry were at the time perceived as far too new and technical to be shared by large communities of researchers. The subsequent results by Bekenstein, Hawking and others on the thermodynamical interpretation of black holes attracted much more interest as they bridged different fields of physics. In fact, methods familiar from quantum field theory such as Bogoliubov transformations could be employed. Many theoretical physicists began to investigate the physics of black holes, as they were regarded as the new atoms of the late twentieth century: they could give hints on the unification between gravity and the other fundamental forces of nature.

Meanwhile smaller communities of mathematical physicists and mathematicians began to systematize mathematical relativity. In fact, the early heroic years had been a bit too frenetic. Some subtle issues, most notably those connected with differentiability of Cauchy hypersurfaces and horizons, had been incompletely or incorrectly treated. Several variations of singularity theorems were explored. Topology change and formation of closed timelike curves were studied. Analysts, in particular, began to obtain significant results on the Cauchy problem for general relativity, and Penrose’s conjectured inequality led to a flourishing of results broadly belonging to geometrical analysis. This phase really continues up to this day.

However, only a few of the mentioned developments pertain to causality theory as this theory mostly focuses on cones. It is easy to prove that the distribution of cones determines the Lorentzian metric only up to a conformal factor. To give an example, of the previous ingredients entering Penrose’s theorem, neither the energy condition nor the notion of trapped surface is really conformally invariant. In fact neither are Einstein’s equations, thus although mathematically one might try to identify causality theory with the body of conformally invariant results of mathematical relativity, it is often the case that it becomes impossible to disentangle causality theory from non-conformally invariant results, and for one good reason: the latter are necessary to make contact with Physics and so to motivate the very study of causality theory.

Though it is a bit difficult to draw the boundary of causality theory within mathematical relativity, by working in causality theory one ends up recognizing some features which distinguish this topic.

Inequalities are more important than equalities: in causality theory Einstein’s equations are seldom used, what are important are really the energy inequalities deduced from those. As a consequence, causality theory is rather robust and largely independent of the dynamical equations of gravity. One might suppose that the Einstein equations should have some implications on causality, but in fact, they are not particularly restrictive. This was recognized long ago with the Gödel solution, and while the causality conditions were refined, many exact solutions with specific causality properties or violations were found (the exact gravitational waves provide a nice laboratory). What is true is that the mentioned energy inequalities restrict the development of causal pathologies provided the Universe starts from causally well behaved conditions.

Causality theory is the least Riemannian among the subjects pertaining to mathematical relativity: while tensorial analogies are useful and might serve to translate results from Riemannian to Lorentzian geometry, the presence of cones and their orientation really leads to a qualitative dynamics which has no analog in the Riemannian world. In fact, it is generically incorrect to regard Lorentzian geometry as a minor, perhaps annoying, variation of Riemannian geometry, as Lorentzian geometry is in fact richer than Riemannian geometry. In fact, it is easy to prove that Riemannian geometry is contained within Lorentzian geometry. Let \((S,g_R)\) be a Riemannian manifold. The product manifold \(M=\mathbb {R} \times S\) endowed with the direct sum metric

is a Lorentzian manifold (M, g) which encodes all the information of \((S,g_R)\). For instance, geodesics on M project to geodesics on S and every geodesic on S comes from such a projection. In practice in Lorentzian geometry the Riemannian manifolds can be identified with instances of product spacetimes (hence static). The converse inclusion does not hold since Riemannian manifolds do not encode any cone dynamics, i.e. any causality theory.

This review aims to give an updated account of causality theory. For each result we tried to present the strongest version, often improving those available in the literature. As for previous references, the most important books containing extensive discussions are Penrose (1972), Lerner (1972), Hawking and Ellis (1973), O’Neill (1983), Wald (1984b), Joshi (1993), Beem et al. (1996) and Kriele (1999). Other more specific review papers with an objective similar to our own are Senovilla (1998), García-Parrado and Senovilla (2005), Minguzzi and Sánchez (2008) and Chruściel (2011).

Since the subject is extensive we could not include the proofs of all the presented results, however, we tried to include almost all proofs with a causality flavor. For instance, we omitted some proofs on the exponential map, Gauss lemma or on the existence of convex neighborhoods. We made this choice because the proofs are lengthy and pertain more to the field of Analysis. They really use analytic arguments and tools that do not show up again in the study of causality theory.

Some specific or technical topics of causality theory have not been discussed in this review. I give a list here pointing the reader to some literature

Chronology violation (time machines) and topology change (Geroch 1967; Tipler 1974, 1977; Yodzis 1972, 1973; Galloway 1983b, 1995; Kriele 1989; Hawking 1992; Ori 1993, 2007; Borde 1997, 2004; Krasnikov 1995, 2002; Minguzzi 2015a, 2016a; Larsson 2015; Lesourd 2018).

Spacetime boundaries (Penrose 1964, 1965c; Schmidt 1971a, b; Geroch et al. 1972; Sachs 1973; Budic and Sachs 1974; Geroch 1977a; Szabados 1987, 1988; Rácz 1987, 1988; Kuang and Liang 1988, 1992; Scott and Szekeres 1994; Harris 1998, 2000, 2004, 2017; Marolf and Ross 2003; García-Parrado and Senovilla 2005; Low 2006; Flores 2007; Flores and Sánchez 2008; Flores and Harris 2007; Sánchez 2009; Chruściel 2010; Flores et al. 2011; Minguzzi 2013; Whale et al. 2015).

Horizons and lightlike hypersurfaces (including regularity issues, area theorem, splitting) (Moncrief and Isenberg 1983; Borde 1984; Isenberg and Moncrief 1985; Kupeli 1987; Chruściel and Isenberg 1993, 1994; Beem and Królak 1998; Friedrich et al. 1999; Galloway 2000; Budzyński et al. 1999, 2001, 2003; Chruściel and Galloway 1998; Chruściel 1998; Chruściel et al. 2001, 2002; Minguzzi 2014, 2015a; Krasnikov 2014; Moncrief and Isenberg 2018).

Hopefully, they will be covered in future versions of this work.

For what concerns the study of singularities, the literature is so vast that we decided to present just a few results beyond the classical ones. Nevertheless, we devoted some space to the exploration and improvement of the classical theorems, for instance we were able to weaken considerably the assumptions in Penrose’s theorem, cf. Theorem 6.33. The new theorem could be useful in the study of black hole evaporation. We have also obtained a singularity theorem sufficiently versatile to be applicable in astrophysics and cosmology, cf. Theorem 6.52.

The review introduces some new causality concepts which we found particularly convenient e.g.: biviability, chronal equivalence, araying sets, causal versions of horismos and trapped sets (Sect. 2.17).

As for the prerequisites, the reader is assumed to be familiar with basic results on differential geometry and on the notion of (pseudo-)Riemannian space, hence with the notions of metric, affine connection, curvature tensor, Lie differentiation, exterior forms and integration over manifolds.

1.2 Notation and terminology

Greek indices run from 0 to n, where \(n+1\) is the dimension of the spacetime manifold M. Latin indices run from 1 to n. We might use the notation \(\mathbf {x}:=(x^1,\ldots ,x^n)\). The Lorentzian signature is \((-,+,\ldots ,+)\). The Minkowski metric is denoted by \(\eta \), so in canonical coordinates \(\eta _{00}=-1\), \(\eta _{ij}=\delta _{ij}\) for \(i,j=1,\ldots , n\), \(\eta _{0 i}=0\), for \(i=1,\ldots , n\). Sometimes for brevity we set \(F(v)=\sqrt{-g(v,v)}\) and \(L=-F^2/2\). Terminologically we might not distinguish between a curve and its image, the intended meaning will be clear from the context. Often, given a sequence \(x_n\), a subsequence \(x_{n_k}\) might simply be denoted \(x_k\). The boundary of a set S can be denoted \(\dot{S}\) or \(\partial S\), the latter choice being sometimes less ambiguous but also less compact. The subset symbol is reflexive, \(S\subset S\). The index placement for the notable tensors is consistent with Misner et al. (1973), the convention on the wedge product is \(\alpha \wedge \beta =\alpha \otimes \beta -\beta \otimes \alpha \) where \(\alpha \) and \(\beta \) are 1-forms (i.e. that of Spivak 1979, which is different from that of Kobayashi and Nomizu 1963). (Sub)manifolds, e.g. hypersurfaces, do not have boundary unless otherwise stated.

1.3 The notion of spacetime

Let V be an \(n+1\)-dimensional vector space, and let \(g:V\times V\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) be a scalar product of Lorentzian signature, that is \((-,+,\ldots ,+)\). We can find a basis \(\{e_\alpha , \alpha =0,1,\ldots , n\}\) of V and associated (canonical) coordinates \(\{v^\alpha \}\) so that if \(v=v^\alpha e_\alpha \) the scalar product reads

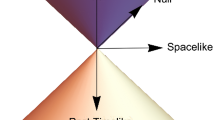

where \(\eta _{\alpha \beta }=0\) if \(\alpha \ne \beta \), \(\eta _{00}=-1\) and \(\eta _{ii}=1\). A vector is calledFootnote 1

Causal vectors might also be called nonspacelike, though this terminology is less common. The coordinate expression for g clarifies that the timelike locus is the union of two disjoint open cones, one in the region \(v^0>0\) and the other in the region \(v^0<0\). We say that V is time-oriented, and simply denoted (V, g), if a choice of cone, termed future, has been made. The other cone is called past. In this case we assume that the above coordinates have been chosen so that the future cone lies in \(v^0>0\) (if this is not the case just redefine \(v^0\rightarrow -v^0\)). The causal vectors are now future or past (directed) depending on the sign of \(v^0\), either positive or negative.

The observer space or indicatrix is

and geometrically is a hyperboloid \(\mathbb {H}^n\).

Definition 1.1

The Minkowski space is the pair (V, g) understood as time oriented.

The Minkowski space serves as a model for the tangent space of a spacetime.

A Lorentz map is an endomorphism \(\varLambda :V\rightarrow V\) which preserves g, i.e. for every \(v,w\in V\),

If \(\varLambda \) sends the future timelike cone into the future timelike cone then it is said to be orthochronous. If V has an orientation and \(\varLambda \) preserves the orientation then \(\varLambda \) is said to be proper.

1.4 Reverse triangle and Cauchy–Schwarz inequalities

In this section \(F:C\rightarrow [0,\infty )\), where \(F(v):=\sqrt{-g(v,v)}\). The following results really extend by continuity to include the case with \(v_1=0\) or \(v_2=0\).

Theorem 1.2

(Reverse Cauchy–Schwarz inequality) Let (V, g) be Minkowski space and \(C\subset V\) the future causal cone. If \(v_1,v_2\in C\) then

where equality holds iff \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) are proportional.

Proof

Let \(v_1\in C\) be timelike and let us choose canonical coordinates such that \(e_0\propto v_1\), then

where equality holds only if \(v_2^i=0\) for all \(i\ge 1\), that is, only if \(v_2\) is proportional to \(v_1\). The inequality for \(v_1\) lightlike follows by continuity. It remains to prove that \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) are proportional if they are both lightlike and the inequality holds with the equality sign, i.e., \(g(v_1,v_2)=0\). Let us choose the canonical coordinates so that \(v_1=a (e_0+e_1)\), \(a>0\), then \(g(v_1,v_2)=0 \Rightarrow v^0_2=v^1_2\), and since \(v_2\) is lightlike \(v_2^k=0\) for \(k\ge 2\), that is, \(v_2 \propto v_1\). \(\square \)

Theorem 1.3

(Reverse triangle inequality) Let (V, g) be Minkowski space and \(C\subset V\) the future causal cone. For every \(v_1,v_2\in C\) we have

with equality if and only if \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) are proportional.

Proof

Let \(v=v_1+v_2\); since v is twice the average of \(v_1,v_2\in C\) and C is strictly convex we have that \(v\in \mathrm {Int} C\) unless \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) are proportional and lightlike. In the latter case the inequality is clear so let us suppose that such case does not apply and hence that v is timelike. We have

Dividing by F(v) we get

where we used the reverse Cauchy–Schwarz inequality. Now notice that if equality holds and v is timelike then in this chain of inequalities the only way of obtaining a final equality is with the Cauchy–Schwarz inequalities used with the equality sign, which means \(v\propto v_1\) and \(v \propto v_2\), which implies that \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) are proportional. If v is instead lightlike we have already shown that \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) are proportional and lightlike. \(\square \)

Notice that F is positive homogeneous: for every \(a>0\), \(F(av)=a F(v)\). We have also

Corollary 1.4

Function \(F:C\rightarrow [0,\infty )\) is concave.

Proof

In fact if \(a,b\in [0,1]\), \(a+b=1\), \(F(av_1+bv_2)\ge F(av_1)+F(bv_2)=a F(v_1)+bF(v_2)\). \(\square \)

It is also easy to prove that the properties of positive homogeneity and concavity imply the reverse triangle inequality (Minguzzi 2019, Proposition 3.4).

1.5 Manifolds

In this work we shall assume the reader to be familiar with the notion of real smooth manifold (Lee 2012). It is also understood that the definition of manifold includes the properties Hausdorff and second countability. All our manifolds will be without boundary unless otherwise specified. Since every real manifold is locally homeomorphic with an open subset of \(\mathbb {R}^{n+1}\), with \(n+1\) the dimension of the manifold, it is also locally compact.

It is useful to recall a few definitions and results from topology (Willard 1970). A topological space is Hausdorff if the open sets separate points. A Hausdorff space is regular if points and disjoint closed sets are separated by open sets. A topological space is metrizable if there is a distance function that induces the topology.

A Hausdorff locally compact space is regular (in fact completely regular). Moreover, every Hausdorff second-countable regular space is metrizable, thus every manifold is metrizable. Every locally compact Hausdorff second-countable space is paracompact, thus every manifold is paracompact.

It is worth to recall that a topological space is paracompact if every open cover admits a locally finite refinement. A Hausdorff topological space is paracompact if and only if it admits a partition of unity, thus manifolds admit partitions of unity. Partitions of unity are really important, for instance they help to define integration over manifolds or to obtain continuous selections of convex bundles over manifolds.

A Lorentzian manifold is just a pair (M, g), where M is a smooth manifold and \(g:M\rightarrow T^*M\otimes _M T^*M\) is a \(C^2\) metric of Lorentzian signature.

The assumptions within the definition of manifold are rather reasonable for our purposes. Suppose second countability and paracompactness were dropped. Due to a theorem by Marathe (1972) paracompactness would be recovered from the assumption of the existence of a pseudo-Riemannian metric or of a connection, ingredients which are clearly necessary for Lorentzian geometry, see also Palomo and Romero (2006). Paracompactness would imply the existence of a partition of unity and hence that of a Riemannian metric, and from here the metrizability of the topological space. Finally, a result in topology states that any connected and locally compact metrizable space is second countable, so both properties are recovered.

1.6 Auxiliary Riemannian metrics

A Riemannian manifold has a definition similar to that of Lorentzian manifold, where now the metric h has Euclidean signature. Given a metric the length of the \(C^1\) curve \(x:[0,1]\rightarrow M\), \(t\mapsto x(t)\), is

while the distance between two points is the infimum over the connecting curves

Sometimes we might denote them \(l_0\) and \(d_0\). The topology of the manifold coincides with the topology induced by \(d^h\), in particular \(d^h\) can be shown to be continuous. The Hopf–Rinow theorem gives some equivalent characterizations for the completeness of (M, h), i.e., in terms of the completeness of \(d^h\)-Cauchy sequences, compactness of closed balls, and completeness of geodesics (Klingenberg 1982; Gallot et al. 1987).

In Lorentzian geometry several constructions make use of an auxiliary Riemannian metric h. This approach might seem unnatural, however Riemannian metrics, particularly complete ones, are indeed useful when it comes to express results which are local, i.e. which hold only over compact sets. To this end the following theorem by Nomizu and Ozeki (1961) is handy

Theorem 1.5

Let M be a connected (second countable) differentiable manifold, then it admits a complete Riemannian metric. If every Riemannian metric is complete then M must be compact.

Since the bundle of Riemannian metrics over M is convex, and since every point admits a Riemannian metric in its neighborhood (as it is clear by using the Euclidean metric in local coordinates), the use of a partition of unity immediately gives that every manifold admits a Riemannian metric. The proof then really shows that for every Riemannian metric there is a complete Riemannian metric in the same conformal class.

1.7 Time orientation

A Lorentzian manifold is said to be time orientable if at every point we can make a choice of future cone for \((T_xM,g_x)\) in such a way that the choice is continuous in \(x\in M\). Here continuity can be understood in several equivalent ways. Let \(C_x\subset T_xM\backslash 0\) be the causal future cone at x, then \(C=\cup _x C_x\) is a continuous cone bundle, that is \(\partial C\backslash 0\) is a continuous hypersurface of the slit tangent bundle \(TM\backslash 0\). Equivalently, it is possible to find a continuous (global) timelike vector field \(x\mapsto v(x)\). With it we can call future that half of the timelike double cone which contains v.

Notice, that in every Lorentzian manifold we can find a local timelike vector field. In fact, given \({\bar{x}} \in M\), we can find a local chart \(\{x^\alpha \}\) in a neighborhood of \({\bar{x}}\) such that \(g(\partial _\alpha ,\partial _\beta )\vert _{{\bar{x}}}=\eta _{\alpha \beta }\). Then, by continuity, \(\partial _0\) is timelike in a neighborhood of \({\bar{x}}\). Since we have a partition of unity at our disposal we could hope to patch together the local fields to get a global timelike vector field. In general this is not possible the obstruction being precisely the condition of time orientability. Nevertheless, every Lorentzian manifold admits a (at most double) covering which is time orientable. Over a connected component it is constructed as follows (Geroch 1970). Let \(p_0\in M\) be a reference point, and consider the family of pairs

Let us introduce the equivalence relation \((p,\gamma )\sim (p',\gamma ')\) if \(p=p'\) and a timelike vector at p, when continuously transferred from p to \(p_0\) along \(\gamma \) and then back to p along \(\gamma '\), does not reverse its time direction. The set of equivalence classes defines a new manifold, called by Geroch the Lorentzian covering. It is really a double covering of the original Lorentzian manifold (M, g). Moreover, it is really M if the Lorentzian manifold is time orientable.

A time orientable Lorentzian manifold is said to be time oriented if a choice of time orientation has been made.

Definition 1.6

A spacetime is a connected non-compact time oriented Lorentzian smooth manifold. It is still denoted (M, g).

It can be noticed that the tangent space \((T_xM,g_x)\) to a spacetime is a Minkowski space. The simplest spacetime is Minkowski spacetime: M admits a single chart whose image is the whole \(\mathbb {R}^{n+1}\), and in the coordinates \(\{x^\mu \}\) of \(\mathbb {R}^{n+1}\),

and \(\partial _0\) is future directed. In other words, the Minkowski spacetime is an affine space modeled over the Minkowski space. The mentioned coordinates are the canonical coordinates for the Minkowski spacetime. Sometimes the notions of Minkowski space and Minkowski spacetime are not distinguished terminologically though the former is a vector space while the latter is an affine space endowed with a translationally invariant metric.

Compact time-oriented Lorentzian manifolds will be referred to as compact spacetimes while, unless otherwise specified, a spacetime will always be non-compact. The physics community has been oriented towards this definition of spacetime by the simple result that compact spacetimes contain closed timelike curves (time travel), cf. Proposition 4.18. It is unlikely that they could represent our actual Universe. Nevertheless, many mathematicians have investigated compact spacetimes. They have some interesting mathematical peculiarities. The reader is referred to the works by Tipler (1979), Galloway (1984, 1986a), Guediri (2002, 2003, 2007), Romero and Sánchez (1995), Sánchez (1997, 2006) and references therein.

Remark 1.7

We recall the famous words of Minkowski: “Henceforth space by itself, and time by itself, are doomed to fade away into mere shadows, and only a kind of union of the two will preserve an independent reality”. This union is the spacetime, which terminologically, in our opinion, should be written as a single word, and not as space-time, precisely due the fact that spacetime cannot be canonically split as the union of space and time. The very word of spacetime reminds us of the main accomplishment of relativity theory, the unification of space and time.

1.8 Existence of Lorentzian metrics

We have recalled that every manifold admits a Riemannian metric. We wish to find conditions that guarantee the existence of a Lorentzian metric.

A continuous line field is a continuous distributions of lines. Let h be a Riemannian metric, then a line field is locally determined by a continuous h-unit vector field v (or \(-v\)) which generates the line.

A manifold M which admits a continuous line field admits a Lorentzian metric. Indeed, \(g=h-2v^\flat \otimes v^\flat \), with \(v^\flat (\cdot )=h(v,\cdot )\), is Lorentzian, for as a quadratic form it is positive on the hyperplane h-orthogonal to v and negative on v. Notice that it does not depend on the sign of v.

The converse holds true as well. If the manifold admits a Lorentzian metric g then it admits a double covering which is time orientable. Thus over the double covering we have a timelike (hence non-vanishing) global vector field v. Let \(x_1\) and \(x_2\) be the counterimages of the point \(x\in M\), and let \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) be the values of v at these points, so that their projections to M belong to different halves of the timelike double cone. The assignment at x of the line generated by the vector \(v_1-v_2\) provides a line field on M (notice that it is independent of which counterimage is called \(x_1\)) .

Similarly, a slight modification of the above argument proves that the existence of a non-vanishing continuous vector field is equivalent to the existence of a spacetime structure (Lorentzian metric plus time orientation), for in the above construction the vector field v is timelike with respect to g.

In fact, the equivalence can be further improved as follows (Steenrod 1970, Theorem 39.7; O’Neill 1983, Proposition 37; Palomo and Romero 2006).

Theorem 1.8

For a smooth manifold M the following properties are equivalent:

- 1.

existence of a Lorentzian metric,

- 2.

existence of a continuous line field,

- 3.

existence of a non-vanishing continuous vector field,

- 4.

existence of a spacetime structure,

- 5.

either M is non-compact, or M is compact and has zero Euler characteristic.

It is worth to recall that a compact manifold whose dimension \(n+1\ge 2\) is odd has zero Euler characteristic.

Example 1.9

(A non-time orientable Lorentzian manifold) Consider \(\mathbb {R}^2\) with Cartesian coordinates (x, y) and metric

Then \(M=[0,1]\times (-1,1)\) where the segment \(\{0\}\times (-1,1)\) is glued to the segment \(\{1\}\times (-1,1)\) with a twist (see Fig. 1), and where the metric is the induced one provides the example we were looking for. This example is really non-orientable. To get an orientable example, glue \(\{0\}\times (-1,1)\) to \(\{2\}\times (-1,1)\) without a twist.

Example 1.10

(A non-orientable spacetime) Start with \((\mathbb {R}^2,g)\) as before but this time let \(M=[0,3]\times (-1,1)\) and the segment \(\{0\}\times (-1,1)\) is glued to the segment \(\{3\}\times (-1,1)\) with a twist. The topology is that of a Möbius strip.

One can ask whether a non-compact manifold admits Lorentzian metrics with stronger properties, say existence of continuous increasing functions (time functions) or bounds on the Ricci tensor of physical relevance. The strongest result in this direction is due to Kokkendorff (2002). The proof makes use of Gromov’s h-principle.

Theorem 1.11

Any noncompact manifold can be given a spacetime structure admitting a time function and such that the sectional curvature is negative over every timelike plane, so in particular \(R(v,v) >0\) for every timelike tangent vector.

1.9 Cone distributions and conformal invariance

In this section we clarify the connection between causal structure and conformal invariance. We need a simple algebraic result (Wald 1984b, Appendix D).

Proposition 1.12

Let V be an \(n+1\)-dimensional vector space, \(n\ge 1\), and let g and \({\bar{g}}\) be two Lorentzian bilinear forms over it. The forms g and \({\bar{g}}\) induce the same (double) cone of causal vectors if and only if there is a constant \(\varOmega ^2>0\) such that \({\bar{g}}=\varOmega ^2 g\).

Proof

The if part is obvious, so let us assume that g and \({\bar{g}}\) induce the same (double) cone of causal vectors, and hence the same double cone of lightlike vectors. There is a basis \(\{e_\mu \}\) of V such that \(g(e_\mu , e_\nu )=\eta _{\mu \nu }\). For every i, \(e_0 \pm e_i\) is g-lightlike, thus

which implies \({\bar{g}}(e_i,e_i)=-{\bar{g}}(e_0,e_0)\), \({\bar{g}}(e_0,e_i)=0\), where \({\bar{g}}(e_0,e_0)<0\) since \(e_0\) is g-timelike and hence \({\bar{g}}\)-timelike. Moreover, for \(i\ne j\), \(e_0 +\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} (e_i+e_j)\) is lightlike, thus

In summary \({\bar{g}}(e_\mu ,e_\nu )=[-{\bar{g}}(e_0,e_0)] \eta _{\mu \nu }\), which concludes the proof. \(\square \)

It has the following important consequence.

Corollary 1.13

Two spacetimes (M, g), \((M,{\bar{g}})\) based on the same manifold M share the same causal cones if and only if there is a function \(\varOmega :M\rightarrow (0,\infty )\) such that \({\bar{g}}=\varOmega ^2 g\), i.e. \({\bar{g}}\) and g are conformally related.

Every non-degenerate bilinear form g on an oriented vector space V induces an alternating multilinear form given by

where \(\epsilon =1\) if the n-ple \((X_0, X_1, \ldots , X_n)\) is positively oriented, and \(\epsilon =-1\) if it is negatively oriented (the determinant on the right-had side vanishes if it is not a basis).

If V is identified with the tangent space to the spacetime manifold \(T_xM\), \(\mu \) is called the volume form associated to the metric g. It can be observed that if \({\bar{g}}=\varOmega ^2 g\) then \({\bar{\mu }}=\varOmega ^{n+1} \mu \), so by fixing the volume form we fix the conformal factor.

Corollary 1.14

Two spacetimes (M, g), \((M,{\bar{g}})\) based on the same oriented manifold M share the same causal cones and the same volume form if and only if \({\bar{g}}= g\), that is, iff they are actually the same spacetime.

This result establishes that a Lorentzian spacetime is nothing but a distribution of round cones and a volume form.

It is interesting to compare the connection, geodesics and curvature for conformally related metrics, \({\bar{g}}=\varOmega ^2 g\). This detailed study can be found in Wald (1984b, Appendix D). Here we just mention the fact that unparametrized lightlike geodesics are really independent of the conformal factor while the affine parameter changes as follows

where c is a constant. It can be observed that the exponent does not coincide with that entering the transformation of proper time: \(\frac{\mathrm{d}{\bar{\tau }} }{\mathrm{d}\tau }=\varOmega \).

1.10 Abstract relations

A relation on M is a subset of the Cartesian product: \(R\subset M\times M\). The relation is closed if it is closed in the product topology and similarly for open. Given two relations \(R_1\) and \(R_2\) the composition is

A relation is transitive if \(R\circ R\subset R\) and idempotent if \(R\circ R=R\). The diagonal \(\varDelta :=\{(p,p):p\in M\}\) acts as an identity for the composition \(\varDelta \circ R=R\circ \varDelta =R\). We say that R is reflexive if \(\varDelta \subset R\). A reflexive and transitive relation is called a preorder and it is idempotent. The inverse or transpose relation is \(R^{-1}:=\{(p,q):(q,p)\in R\}\). A relation is antisymmetric if

or equivalently \(R\cap R^{-1}=\varDelta \). An order or a partial order is an antisymmetric preorder. A total order is an order for which any two elements are comparable: \(R\cup R^{-1}=M\times M\). We also define the increasing hull or R-future of a point by

and the decreasing hull or R-past of a point by

They extend to the R-future (past) of a set as follows

An R-diamond is a set of the form \(R^+(p)\cap R^-(q)\) for some \(p,q\in M\).

1.11 Causality relations

In Sect. 1.3 we have given the definition of causal, timelike and lightlike vector. A piecewise \(C^1\) curve \(x:I \rightarrow M\), \(t \mapsto x(t)\), \(I\subset \mathbb {R}\) an interval of the real line, is said to be causal, timelike or lightlike if the tangent vector has the corresponding future causal character at every point. Notice that by our definition of causal vector we have \(\dot{x} \ne 0\) at every point of differentiability, i.e. causal curves are regular. Notice also that all our causal curves will be future directed unless otherwise specified. The concatenation of causal curves gives a causal curve, and similarly in the timelike or lightlike cases.

On spacetime we can define relations connected to the notions of causal or timelike curves. They are the causal relation

and the chronological relation

Clearly, \(I\cup \varDelta \subset J\). As an example, the chronological relation for Minkowski spacetime is given by the open set

while the causal relation is obtained by replacing > with \(\ge \).

The horismos relation is the difference \(\mathcal {E}=J\backslash I\). We shall also write

\(p\le q\) for \((p,q)\in J\),

\(p<q\) for “\(p\le q\) and \(p\ne q\)”,

\(p\ll q\) for \((p,q)\in I\), and

\(p\rightarrow q\) for \((p,q)\in J\backslash I\).

For the relation J the J-future and J-past of a point are denoted \(J^\pm (p)\) and we speak of causal future (past) of the point. Similarly \(I^+(p)\) denotes the chronological future of p, and \(E^+(p):=J^+(p)\backslash I^+(p)=\mathcal {E}^+(p)\) denotes the future horismos of p. We stress that given a set S, we write

We introduced a calligraphic notation for the relation \(J\backslash I\) precisely to avoid conflicts with the general notation introduced in Eq. (1.2).

Lemma 1.15

Let S be any set then \(E^{+}(S) \subset \mathcal {E}^+(S)\).

Proof

If \(q \in E^{+}(S)\subset J^{+}(S)\) then there is \(p\in S\) such that \(q \in J^{+}(p)\), but we cannot have \(q \in I^{+}(p)\), as it would imply \(q \in I^{+}(S)\). Thus \(q \in E^{+}(p)\). \(\square \)

The J-diamonds, i.e. the sets of the form \(J^+(p)\cap J^{-}(q)\) for \(p,q\in M\), are also called causal diamonds.

Sometimes we might need to consider the causal relation for a subset \(U\subset M\), which is defined as above but with the causal curves having image in U. Such a causal relation is denoted \(J_U\) or \(J_{(U,g)}\) and must not be confused with \(J\cap (U\times U)\). Also \(J^+_U(p)\) might be denoted \(J^+(p, U)\) and similarly in the past and chronological cases. Sometimes we might need to consider different metrics \(g'\), in which case we might write \(J_{g'}\) or \(J_{(M,g')}\) for the corresponding causal relation.

Given two Lorentzian metrics over M we write \(g\le g'\) if at every point the future causal cone of g is included in the future causal cone of \(g'\), and we write \(g<g'\) if the future causal cone of g is included in the future timelike cone of \(g'\).

Proposition 1.16

The causal relation J is transitive and reflexive. The chronological relation I is transitive and open.

Notice that the openness of I implies that of \(I^+(p)\) and \(I^-(p)\) for every point p and hence that of \(I^+(S)\) and \(I^-(S)\) for every subset \(S\subset M\).

Proof

The only non-trivial statement is the openness of I. Let \((p,q)\in I\) then there is a timelike curve \(\gamma \) from p to q. Let \(v={\dot{\gamma }}\in T_q M\) be the tangent to the curve at q. Let us introduce local coordinates in a neighborhood U of q such that \(g_q=-(\mathrm{d}x^0)^2+\sum _i (\mathrm{d}x^i)^2\), and let \({\bar{g}}=-(1-\epsilon )(\mathrm{d}x^0)^2+\sum _i (\mathrm{d}x^i)^2\) where \(\epsilon >0\) is so small that v is both g-timelike and \({\bar{g}}\)-timelike. By continuity, in a neighborhood \(V\subset U\) of q, \({\dot{\gamma }}\) is \({\bar{g}}\)-timelike and the \({\bar{g}}\)-causal cone is contained in the g-timelike cone, i.e. \({\bar{g}}<g\). As shown previously, the chronological relation is open in a Minkowski spacetime, thus taking \(r\in \gamma \cap V\backslash \{q\}\), the points of a whole neighborhood \(U_q\) of q can be reached from r with \({\bar{g}}\)-timelike (and hence g-timelike) curves. The argument can be repeated time-dually for p, by taking \(r'\) sufficiently close to p so that \((r',r)\in I\). Then by concatenating the timelike curves we conclude \(U_p\times U_q\subset I\). \(\square \)

The causal relation is not necessarily closed (cf. Fig. 2), a fact which ultimately is responsible for the variety of different causality conditions that can be placed on a spacetime. Later on we shall introduce two closed and transitive relations, namely the Seifert’s relation \(J_S\) and Sorkin and Woolgar’s K relation.

1.12 Non-decreasing functions

We introduce families of non-decreasing functions over causal curves which will be useful in what follows.

Definition 1.17

A function \(t:M\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) which satisfies \(p\le q \Rightarrow t(p)\le t(q)\) is said to be isotone or causal.

The notion of isotone function might be defined for any relation R on M, not just \(R=J\). One says that the function t is a R-utility if it is R-isotone and additionally: \((p,q)\in R\) and \((q,p)\notin R\) \(\Rightarrow t(p)<t(q)\).

Proposition 1.18

If an isotone function is differentiable at p, then \(\nabla t(p)\) is past directed causal or zero.

Proof

If \(w=-\nabla t(p)\) is non zero and not future directed causal then we can find a future directed timelike vector v such that \(g(w,v)> 0\), hence \(-\mathrm{d}t(v)=-g(\nabla t,v)> 0 \), which contradicts the fact that t cannot decrease over timelike curves with tangent v at p. \(\square \)

Monotone functions on the real line are known to be (Fréchet-)differentiable almost everywhere. An analogous result holds true for isotone functions.

Theorem 1.19

Every isotone function \(f:M\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) on (M, g) is almost everywhere continuous and almost everywhere differentiable. Moreover, it is differentiable at \(p\in M\) iff it is Gâteaux–differentiable at p. Finally, if \(x:I\rightarrow M\) is a timelike curve, the isotone function f is upper/lower semi-continuous at \(x_0=x(t_0)\) iff \(f\circ x\) has the same property at \(t_0\).

A similar result is contained in Rennie and Whale (2016) but, unfortunately, the proof of the non-trivial almost differentiability statement is incorrectFootnote 2 (cf. their Lemma A.4-5). The proof below takes advantage of a previous proof on the product order of \(\mathbb {R}^k\) by Chabrillac and Crouzeix (1987). Notice that our proof remains unaltered for continuous distributions of closed cones with non-empty interior as considered in Minguzzi (2019). Also we might replace in the statement the isotone assumption with the weaker condition \(p\ll q \Rightarrow f(p)\le f(q)\).

Proof

It is sufficient to prove the result in a neighborhood of a chosen point \(q\in M\). Let \(\{e_a\}\) be a holonomic basis of future directed timelike vector fields, where \(e_a=\partial /\partial x^a\), \(x^a(q)=0\), \(a=0,1,\ldots , n\). By using these coordinates we can identify a neighborhood of q with a neighborhood of \(O\ni 0\), \(O\subset \mathbb {R}^{n+1}\). At every point the future timelike cone contains the cone \(K=\{v^a e_a: v^a \ge 0, a=0,\ldots , n\}\), thus the spacetime isotone function \(f:O \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) is isotone also for the canonical product order \((x_0, \ldots , x_n) \le (y_0,\ldots , y_n)\) iff \(x_a\le y_a\) for every a. The main statement is now a consequence of the results in Chabrillac and Crouzeix (1987), Theorems 6 and 14. The proof of the last statement is as in Proposition 5 of the mentioned reference, it is sufficient to replace \(\le \) with the causal order and \(f(x_0+td)\) with f(x(t)). \(\square \)

Definition 1.20

A continuous function \(t:M\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) such that \(p\ll q \Rightarrow t(p)<t(q)\) is a semi-time function.

We shall see later (Theorem 2.27) that \(J\subset {\bar{I}}\), thus by continuity we have that the semi-time functions are isotone. Semi-time functions were introduced by Seifert (1977), see also Ehrlich and Emch (1992b).

Definition 1.21

A continuous function \(t:M\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) which satisfies \(p< q \Rightarrow t(p)<t(q)\) is a time function.

Every time function is a semi-time function, hence isotone.

Definition 1.22

A \(C^1\) function \(t:M\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) such that \(\mathrm{d}t\) is positive over the future causal cone (equivalently \(\nabla t\) is past directed) is called temporal function.

Temporal functions are time functions.

Theorem 1.23

For a function t differentiable at \(p\in M\) the inequalities at p

- (a)

for every future directed causal vector v, \(\mathrm{d}t(v) \ge \sqrt{-g(v,v)}\),

- (b)

\(-g(\nabla t,\nabla t)\ge 1\), and \(\nabla t\) is past directed (clearly timelike).

are equivalent.

I mention that in Finslerian theories (a) \(\Rightarrow \) (b) does not necessarily hold without conditions on the behavior of the Finsler function at the boundary of the causal cone.

Proof

(b) \(\Rightarrow \) (a). Let v be future directed causal, then by the reverse Cauchy-Schwarz inequality

thus if \(-g(\nabla t,\nabla t)\ge 1\) then t satisfies (a).

(a) \(\Rightarrow \) (b). Condition (a) implies that f is isotone so \(\nabla f\) is past directed causal or zero. Moreover, over future directed timelike vectors (a) implies \(\mathrm{d}f \ne 0\). Suppose that \(w=-\nabla f(p)\) is lightlike, so that \(\mathrm{d}f(w)=0\). Let n be a null vector such that \(g(n,w)=-1/2\), then the vector \(v(s)=w+sn\), \(g(v,v)=-s\), for \(s\ge 0\), is causal, thus by the steep condition \(s \mathrm{d}f(n)=\mathrm{d}f(v(s))\ge \sqrt{s}\), which is impossible for sufficiently small s. We conclude that \(\nabla f\) is past directed timelike. Now, \(\mathrm{d}t(v)\ge \sqrt{-g(v,v)}\) holds also for \(v=-\nabla t\), which, using the fact that \(\nabla t\) is timelike, gives \(-g(\nabla t,\nabla t) \ge 1\). \(\square \)

Definition 1.24

A function t which satisfies the equivalent conditions in the previous theorem is steep at p. A \(C^1\) function \(t:M\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) which is steep at every point is a steep function.

Steep functions first appeared in a work by Parfionov and Zapatrin (2000) on the Lorentzian analog of Connes distance formula though the terminology comes from Müller and Sánchez (2011). These functions also proved useful in the study of the isometric embedding problem (Müller and Sánchez 2011; Minguzzi 2019).

Proposition 1.25

An isotone function \(f:M\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) is almost everywhere steep iff

Proof

If f is almost everywhere steep then for almost every p, \(\sqrt{-g(\nabla f,\nabla f)}(p)\) \( \ge 1\), that is, Eq. (1.4). Conversely, if f is isotone and Eq. (1.4) holds, then by Proposition 1.18 and Theorem 1.19 f is differentiable almost everywhere with past directed causal or zero gradient, but by Eq. (1.4) it satisfies \(-g(\nabla t,\nabla t)\ge 1\) almost everywhere thus it has a.e. past directed timelike gradient, and hence it is almost everywhere steep. \(\square \)

The remainder of the section uses the notion of Lorentzian distance and some of its basic properties, c.f. Sect. 2.9.

Definition 1.26

A function \(f:M\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) which satisfies for every \((p,q)\in I\)

is a rushing function. A rushing time function is a rushing time.

If a rushing function exists then the spacetime is chronological because d is finite.

The codomain of f could be extended to \([-\infty , +\infty ]\), but the previous statement would not hold. In order to simplify the following statements we shall not consider this generalization.

Our terminology here comes from the fact that given a proper time–parameterized timelike curve \(\gamma :I \rightarrow M\), introduced the f-time \(f(\gamma (t))\), we have for every \(t_1\le t_2\), \(f(\gamma (t_2))\ge f(\gamma (t_1))+ \varDelta t\), i.e. the f-clock is faster than the physical proper time clock. So we are just asking the f-time to be rushing for every observer. Clearly, rushing functions are isotone hence almost everywhere continuous and differentiable.

Proposition 1.27

For a \(C^0\) rushing function Eq. (1.5) holds for \((p,q)\in {\bar{J}}\).

Proof

Let \((p,q)\in \bar{J}\), let \(p_n\ll p\), \(p_{n+1}\gg p_n\), be a sequence such that \(p_n\rightarrow p\), and similarly, let \(q_n\gg q\), \(q_{n+1}\ll q_n\), be a sequence such that \(q_n\rightarrow q\). Since I is open, \((p_n,q_n)\in I\) (here we are making use of Theorem 2.24 that shall be proved later on), thus \(f(q_n)-f(p_n)\ge d(p_n,q_n)\), so \(f(p)-f(q)=\liminf _n [f(q_n)-f(p_n)]\ge \liminf _n d(p_n,q_n) \ge d(p,q)\). \(\square \)

A theorem analogous to the following one can be found in Rennie and Whale (2016). We give this version because theirs uses a different ‘norm’ and because their proof runs into some problems (see the previous footnote).

Theorem 1.28

The rushing functions are precisely the isotone almost everywhere steep functions. The \(C^1\) rushing functions are precisely the steep functions. The \(C^0\) rushing functions are precisely the \(C^0\) almost everywhere steep functions.

Notice that it is not true that the almost everywhere steep functions are isotone (just suitably change a \(C^1\) steep function at some points).

Proof

Let f be rushing and let p be a differentiability point of t. We have already proved that (M, g) is chronological thus \(d(p,p)=0\). Let C be a convex neighborhood of p, let \(d^C\) be the Lorentzian distance of \((C,g\vert _C)\), and let \(v\in T_pM\) be future directed timelike, then

where \(s\mapsto x(s)\) is the geodesic starting from p with velocity v, and where we used the fact that \(d\vert _{C\times C}\ge d^C\). By continuity the inequality extends to v lightlike, thus the inequality proves that f is an almost everywhere steep function.

For the converse, let \((p,q)\in I\), by the lower semi-continuity of the Lorentzian distance for every \(\epsilon >0\) there are open neighborhoods \(U\ni p\), \(V\ni q\), such that for every \((p',q')\in U\times V\), \(d(p',q')\ge d(p,q)-\epsilon \), if d(p, q) is finite, or \(d(p',q')>1/\epsilon \) if d(p, q) is infinite. Let \({\bar{p}}\in I^+(p,U)\) and \({\bar{q}}\in I^-(q,V)\), be such that \(({\bar{p}},{\bar{q}})\in I\). Let \(\epsilon >0\) and let \(x:[0,1] \rightarrow M\), \(x(0)={\bar{p}}\), \(x(1)={\bar{q}}\), be a \(C^1\) timelike curve such that \(\ell (x)> d({\bar{p}},{\bar{q}})-\epsilon \), if \(d({\bar{p}},{\bar{q}})\) is finite, or \(\ell (x)>1/\epsilon -\epsilon \) if \(d({\bar{p}},{\bar{q}})\) is infinite. So if d(p, q) is infinite we have \(\ell (x)>1/\epsilon -\epsilon \) independently of the finiteness of \(d({\bar{p}},{\bar{q}})\).

Let us construct a tubular neighborhood of x, of coordinates \((t,{\varvec{x}})\), having the topology \(C:=[0,1]\times B\) of a cylinder, where \(B\subset \mathbb {R}^n\) is a ball. We can find the radius of the ball so small that \(\partial _t\) is timelike over the cylinder and the balls \(t=0\) and \(t=1\), namely the bases of the cylinder, are contained in \(I^+(p,U)\) and \(I^-(q,V)\). Let \(x(t,{\varvec{x}})\) be the point determined by the coordinates \((t,{\varvec{x}})\). We regard f as a function over the coordinated cylinder. The curves \(t\mapsto x_{{\varvec{x}}}(t)=x(t, {\varvec{x}})\) (we have a curve for any choice of constants \({\varvec{x}}\)) that thread the cylinder are timelike, start from \(I^+(p,U)\) and end in \(I^-(q,V)\). Notice that \(\partial _t\) is continuous so the length of the curves is a continuous function of \(\mathbf{x}\). The radius of the ball can be chosen so small that they all have length larger than \(\ell (x)-\epsilon \). Now, let E be the subset of the cylinder at which f is differentiable, and for every \({\varvec{x}}\in B\), let \(E_{{\varvec{x}}}\subset [0,1]\) be the set of those s, such that f is differentiable at \(x_{{\varvec{x}}}(s)\). Then the coordinate volume of the cylinder coincides with the volume of E, a condition which by Fubini-Tonelli reads \(\int _B \mathrm{d}x^1 \ldots \mathrm{d}x^n[\int _{E_{{\varvec{x}}}} \mathrm{d}t-1]=0\), so for almost every \(\mathbf{x}\), \(E_{{\varvec{x}}}\) has full measure 1. So there is a timelike curve \(s \mapsto {\tilde{x}}(s)\) with tangent \(\partial _t\) over whose image f is differentiable almost everywhere. Let \({\tilde{p}}\) and \({\tilde{q}}\) be its endpoints. We have

where in the first inequality we used the fact that f is isotone (one can avoid to use the isotone property in the first inequality, provided one assumes continuity of f and takes U and V so small that the final inequality gets corrected by some \(2\epsilon \). Proceeding in this one one proves the last statement of the theorem). But if d(p, q) is finite then \(d({\bar{p}},{\bar{q}})\) is finite and we have

so by the arbitrariness of \(\epsilon \) we get that \(f(q)-f(p)\ge d(p,q)\). If instead, d(p, q) is infinite we get

so by the arbitrariness of \(\epsilon \) we get that f cannot be finite. The contradiction proves that if there is an isotone almost everywhere steep function f, then the Lorentzian distance is finite and that the function f is rushing. \(\square \)

We have the following relative strengths for functions \(f:M\rightarrow \mathbb {R}\)

A last useful definition is

Definition 1.29

A Cauchy time function is a time function such that each of its level sets is intersected by every causal curve.

In particular, Cauchy time functions have image \(\mathbb {R}\).

Other special time functions have been introduced in the literature, e.g. quasi-time functions (Ehrlich and Emch 1992b) and cosmological time functions (Andersson et al. 1998).

1.13 Recovering causality relations

We have seen that in a spacetime it is quite natural to define the triple of binary relations I, J and \(\mathcal {E}\) (or \(\ll \), \(\le \) and \(\rightarrow \)). Since \(\mathcal {E}\) is just the difference of the other two, it is clear that given two relations it is possible to recover the third.

Later on we shall prove that some causality conditions on spacetime guarantee that these binary relations can be recovered from just one causality relation of the triple. Kronheimer and Penrose (1967) suggested to define two new relations starting from a given one as follows.Footnote 3

Definition 1.30

Let \(\ll , \le , \rightarrow \) (\(I, J, \mathcal {E}\)) be binary relations on a set M (here the relations and M are abstract entities, possibly unrelated to a Lorentzian manifold). We define the associated relations

- 1.

Starting from \(\le \):

- (a)

\(p\rightarrow ^{(\le )} q\) \(\Leftrightarrow \) \(p\le q\) and any proper subset \(J^+(p')\cap J^-(q')\) of \(J^+(p)\cap J^-(q)\) ordered by \(\le \) is order homeomorphic to [0, 1].

- (b)

\(p \ll ^{(\le )} q\) \(\Leftrightarrow \) \(p \le q\) and not \(p \rightarrow ^{(\le )} q\).

- (a)

- 2.

Starting from \(\rightarrow \):

- (a)

\(p \le ^{(\rightarrow )} q\) \(\Leftrightarrow \) \(p=p_1 \rightarrow p_2 \dots \rightarrow p_{n-1}\rightarrow p_n=q\) for some finite sequence \(p_1, \dots ,p_n \in M\).

- (b)

\(p \ll ^{(\rightarrow )} q\) \(\Leftrightarrow \) \(p \le ^{(\rightarrow )} q\) and not \(p \rightarrow q\).

- (a)

- 3.

Starting from \(\ll \):

- (a)

\(p \le ^{(\ll )} q\) \(\Leftrightarrow \) \( I^+(p) \supset I^+(q) \) and \(I^-(p) \subset I^-(q)\).

- (b)

\(p \rightarrow ^{(\ll )} q\) \(\Leftrightarrow \) \(p\le ^{(\ll )} q\) and not \( p \ll q\).

- (a)

It is worth to recall that the empty set admits just one relation (the empty set) which is a total order.

We anticipate the result which establishes under which causality conditions recovery of the triple is really possible. Notice that the causality condition in 2 has been improved with respect to the paper by Kronheimer and Penrose (1967) (and Minguzzi and Sánchez 2008) (they assumed strong causality).

Theorem 1.31

Let (M, g) be a (Lorentzian) spacetime and let \(\ll ,\le ,\rightarrow \) be the usual chronological, causal, and horismos relations.

- 1.

In a causal spacetime (Theorem 4.33)

$$\begin{aligned} \rightarrow ^{(\le )}=\rightarrow , \qquad \ll ^{(\le )}=\ll . \end{aligned}$$ - 2.

In a distinguishing spacetime (Theorem 4.66)

$$\begin{aligned} \le ^{(\rightarrow )}=\le , \qquad \ll ^{(\rightarrow )}=\ll , \end{aligned}$$ - 3.

In a causally simple spacetime

$$\begin{aligned} \le ^{(\ll )} = \le , \qquad \rightarrow ^{(\ll )}=\rightarrow \end{aligned}$$

1.14 Causal convexity and first causality properties

Definition 1.32

Given two sets \(U\subset V\subset M\), we say that U is causally convex in V (or simply causally convex if \(V=M\)) if every causal curve \(x:[0,1]\rightarrow V\) such that \(x(0),x(1)\in U\) has image contained in U.

Clearly, if U is causally convex in V, and V is causally convex in W then U is causally convex in W. Notice that if U is causally convex

The converse does not hold: let M be \(1+1\) Minkowski spacetime of coordinates \(\{t,x\}\), and let \(U=\{p:x(p)=0\}\).

We say that a point \(p\in M\) admits an arbitrarily small neighborhood U with property P, if for every neighborhood \(V\ni p\), we can find \(U\subset V\), \(p\in U\), satisfying property P.

Lemma 1.33

At every point \(p\in M\) we can find local coordinates \(\{x^\mu \}\) such that \(x^\mu (p)=0\), \(\{e_\mu :=\partial _\mu \}\) is a canonical basis of \((T_pM,g_p)\), i.e., \(g(e_\mu , e_\nu )=\eta _{\mu \nu }\) with \(e_0\) future directed, and defining \(g^\epsilon =-(1+\epsilon ) (\mathrm{d}x^0)^2+ \mathrm{d}\mathbf {x}^2\), \(\epsilon \in (-1,1)\), we can find \(\epsilon _+>0\) and \(\epsilon _-<0\), such that in a neighborhood of p, \(g^{\epsilon _-}<g<g^{\epsilon _+}\). Moreover, in this neighborhood for every g-causal vector v

Proof

The inclusion of the cones can be easily checked at p, so the validity in a neighborhood follows by continuity. Every g-causal vector is \(g^{\epsilon _+}\)-timelike, thus \((1+\epsilon _+) [\mathrm{d}x^0(v)]^2>(\mathrm{d}\mathbf {x})^2(v)\). \(\square \)

A closed causal curve \(x:[0,1]\rightarrow M\) is one for which \(x(0)=x(1)\) (possibly \(\dot{x}(0)\ne \dot{x}(1)\)). A similar definition holds in the timelike case. Clearly no point in a closed causal curve can admit arbitrarily small causally convex neighborhoods.

We need to define a few basic causality properties.

Definition 1.34

A spacetime is

- 1.

chronological: if it does not admit any closed timelike curve,

- 2.

causal: if it does not admit any closed causal curve,

- 3.

strongly causal: if it admits arbitrarily small causally convex neighborhoods at every point.

Observe that the properties are ordered from the weakest to the strongest, and that in 3 arbitrarily small is important, for the set M is causally convex and a neighborhood for every point.

Theorem 1.35

Every point \(p\in M\) admits a local basis \(\{V_k, k\ge 1\}\), for the topology such that for every k

- (a)

\(\overline{V_{k+1}} \subset V_k\),

- (b)

\(V_{k+1}\) is causally convex in \(V_k\) (and hence in \(V_1\)),

- (c)

\((V_k,g)\) is strongly causal,

- (d)

Let h be a Riemannian metric; on \((V_k,g)\) the h-arc length of any causal curve contained in \(V_k\) is bounded by a positive constant c(k) which goes to zero for \(k\rightarrow +\infty \),

- (e)

\(V_k\) is relatively compact.

Moreover, if (M, g) is strongly causal then \(V_1\) can be chosen causally convex so all the elements of the local basis are causally convex.

Proof

Let \(g^{\epsilon _+}\) be the metric in a neighborhood U of p mentioned in Lemma 1.33. Let \(q_n\) be such that \(x^0(q_n)=1/n\), \(x^i(q_n)=0\), and similarly let \(r_n\) be such that \(x^0(r_n)=-1/n\), \(x^i(r_n)=0\). Let

then for sufficiently large N, \(\partial V_k\cap \partial U=\emptyset \). The properties (a)-(c) are easily checked since if A is causally convex in B with respect to a metric g then the same holds using a metric \(g'<g\). Property (d) follows from the inequality (1.6), from the fact that \(\vert x^0\vert <1/n\) on \(V_n\), and from the Lipschitz equivalence of Riemannian norms over compact sets.

If (M, g) is strongly causal then p admits a causally convex set W contained in \(V_1\). For some sufficiently large k, \( V_k\subset W\), and any causal curve \(\sigma \) with endpoints in \(V_k\) has endpoints in W thus \(\sigma \) is contained in W and hence in \(V_1\), but since \(V_k\) is causally convex in \(V_1\), \(\sigma \) is contained in \(V_k\), i.e. \(V_k\) is causally convex. Now renumber the sequence starting from \(V_k\rightarrow V_1\). \(\square \)

Remark 1.36

The construction appearing in the proof of this theorem contains much more information than is conveyed by the statement. For instance, it can be observed that the function \(x^0:V_k \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) is a continuous function which increases over every causal curve of \((V_k,g^{\epsilon _+})\) and hence of \((V_k,g)\) (we shall see later that this property is known as stable causality and that in fact, \((V_k,g)\) shares the strongest causality property according to the causal ladder of spacetimes, namely globally hyperbolicity).

2 Some preliminaries

In this section we explore the local properties of the exponential map and its consequences. Some of these results are really quite technical already in the \(C^2\) case, in fact most proofs found in the literature are given for the \(C^\infty \) metric case. A closer investigation shows that the results of this section really require just a \(C^{1,1}\) assumption on the metric, so that most of causality theory can be generalized to this regularity class (Minguzzi 2015b; Kunzinger et al. 2014a, b). For most of the proofs we shall follow Minguzzi (2015b).

2.1 The exponential map

A geodesic is a stationary point of the functional (with a prime we denote differentiation, typically with respect to a parameter s, if the parameter is t we often use a dot)

where \(x\in C^1([s_0,s_1])\) and \(L(x,v)=\frac{1}{2} g_x(v,v)\).

Let \(x^\mu :U\rightarrow \mathbb {R}^{n+1}\) be a local chart where U is an open subset. Every chart induces a chart \((x^\mu , v^\mu ):\pi ^{-1}(U)\rightarrow \mathbb {R}^n\times \mathbb {R}^n\), on the tangent bundle \(\pi : TU\rightarrow U\).

The Euler–Lagrange equations determining the geodesic read, in the local chart, as a second order ODE defined just over U

where \(\varGamma _{\alpha \beta }^\mu \) is the Christoffel symbol for the Levi-Civita connection. Since g is \(C^2\) the right-hand side is Lipschitz and so by the Picard–Lindelöf theorem for any given initial condition \(x(0)=x_0\), \(\dot{x}(0) = \dot{x}_0\) the solution exists and is unique. In fact, since \(\varGamma \) is \(C^1\) the geodesics are \(C^3\) and the dependence on initial conditions is \(C^1\).

The Lagrangian L is constant over the geodesics because, using the Euler–Lagrange equations and the positive homogeneity of degree two of L

Its constancy implies that the causal character of the tangent vector is preserved throughout the whole domain of definition of the geodesic, so geodesics are said to be timelike, lightlike or spacelike depending on the causal character of their tangent vector.

Let \(v\in TM\backslash 0\), and let \(\gamma _v(t)\) be the unique geodesic which starts from \(\pi (v)\) with velocity v. The set \(\varOmega \) is given by those v for which the geodesic exists at least for \(t\in [0,1]\). The exponential map \(\exp :\varOmega \rightarrow M\times M\) is given by

while the pointed exponential map at \(p \in M\), is \(\exp _p:\varOmega _p \rightarrow M\), \(\varOmega _p=\varOmega \cap \pi ^{-1}(p)\), \(\exp _p v:=\gamma _v(1) =\pi _2(\exp v) \). By the homogeneity of degree two of \(\varGamma ^\mu _{\alpha \beta } v^\alpha v^\beta \) on velocities we have

thus the set \(\varOmega \) (and \(\varOmega _p\)) is star-shaped in the sense that if \(v\in \varOmega \) then \(s v\in \varOmega \) for every \(s\in [0,1]\). Equation (2.3) clarifies that it makes sense to call affine the geodesic parameter, for any affine reparametrization of a geodesic gives a curve which solves the geodesic equation.

The following result is consequence of the inverse function theorem on the diagonal of \(M\times M\).

Theorem 2.1

Let M be a manifold endowed with a \(C^1\) connection.

- \((\exp )\):

The set \(\varOmega \) is open in the topology of TM. The exponential map \(\exp :\varOmega \rightarrow M\times M\), \(\varOmega \subset TM\), provides a \(C^1\) diffeomorphism between an open star-shaped neighborhood of the zero section and an open neighborhood of the diagonal of \(M\times M\).

- \((\exp _p)\):

For every \(p\in M\) the set \(\varOmega _p\) is open in the topology of \(T_pM\). The pointed exponential map \(\exp _p:\varOmega _p \rightarrow M\), \(\varOmega _p \subset T_pM\), provides a \(C^1\) diffeomorphism from a star-shaped open subset of \(\varOmega _p\) and an open neighborhood of p.

A proof can be found in Minguzzi (2015b).

2.2 Convex neighborhoods

Definition 2.2

An open neighborhood N of \(p\in M\) is called normal if there is an open star-shaped subset \(N_p\subset \varOmega _p\) such that \(\exp _p:N_p \rightarrow {N}\) is a \(C^1\) diffeomorphism.

Definition 2.3

An open set \(C\subset M\) is called convex normal if it is a normal neighborhood of each of its points. We shall say that C is strictly convex normal if C is convex normal and any two points of \(\bar{C}\) are connected by a unique geodesic contained in C but for the endpoints.

Theorem 2.4

Let M be a manifold endowed with a \(C^1\) connection. Let O be an open neighborhood of \(p\in M\). Then there is a strictly convex normal neighborhood C of p contained in O, such that \(\exp \) establishes a \(C^1\) diffeomorphism between an open star-shaped subset of TC and \(C\times C\).

Moreover, for every chart \(\{x^\mu \}\) defined in a neighborhood of p, C can be chosen equal to the open ball \(B(p,\delta )\) for any sufficiently small \(\delta \) (the ball is defined through the Euclidean norm induced by the coordinates).

The local length minimization property of geodesics in Riemannian spaces, or the local Lorentzian length maximization property of causal geodesics in Lorentzian manifolds, are proved passing through Gauss’ Lemma.

Definition 2.5

Let C be a convex normal set, let \(p,q\in C\) and let \(x: [0,1]\rightarrow C\), \(x(0)=p\), \(x(1)=q\), be the unique geodesic connecting them. The vector \(\dot{x}(1)\) is denoted P(p, q) and called position vector.

Theorem 2.6

(Gauss’ Lemma) Let \(p\in M\), let N be a normal neighborhood of p and let \(v\in \exp _p^{-1}\!\! N\backslash 0\). Let \(w\in T_p M\sim T_v(T_p M)\). Then

Moreover, the function \(D^2_p:N \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) defined by

is \(C^{2}\) in q and

where \(P(p,q):= \gamma '_{\exp ^{-1}_p q}(1)\) is the position vector of q with respect to p. Thus the level sets of \(D^2_p\) are orthogonal to the geodesics issued from p. Finally, on a convex normal set C the function \(D^2:C\times C \rightarrow \mathbb {R}\) defined by

is \(C^2\) and its differential is

where \(v_p\in T_pM\), \(v_q\in T_qM\).

A proof of the previous result can be found in Minguzzi (2015b, Theorem 5).

The following result was proved only recently in Minguzzi (2015b, Corollary 2). The proof is quite technical so it is omitted. In short it states that the topological basis can be chosen to have the best convexity and causality properties.

Theorem 2.7

The basis \(\{V_k\}\) for the topology mentioned in Theorem 1.35 can really be chosen so that, additionally, the sets \(V_k\) are strictly convex normal and globally hyperbolic.

Without this result one is forced to phrase some arguments by using a few nested neighborhoods, some convex and other globally hyperbolic, so as to get some desired property. This sort of involved construction is common in references devoted to causality theory. Thus, although this result is not necessary for the development of causality theory, it might be used to simplify some proofs.

2.3 Causal AC-curves

So far we considered only piecewise \(C^1\) curves, but for what follows we need to weaken their differentiability properties so as to work with a family which is closed under a suitable notion of limit.

A curve \(\sigma :[a,b]\rightarrow M\) will be called absolutely continuous (an AC-curve for short) if its components in one (and hence every) local chart are locally absolutely continuous. Equivalently, introducing a complete Riemannian metric on M, and denoting by \(\rho \) the corresponding distance, \(\sigma \) is absolutely continuous if it satisfies locally the usual definition of absolute continuity between (topological) metric spaces. Since every pair of Riemannian metrics over a compact set are Lipschitz equivalent, and M is locally compact, this definition does not depend on the metric chosen. Analogously, we can define the concept of Lipschitz curve.

We shall say that an AC-curve \(\sigma :[a,b]\rightarrow M\), \(t\mapsto \sigma (t)\), is a (future directed) causal AC-curve if \({\dot{\sigma }}\) is (future directed) causal almost everywhere. We do not need to define a notion of timelike AC-curve.

Remark 2.8

Lipschitz reparametrizations. Over every compact set \(A\subset U\) we can find a constant \(a>0\) such that for every \(x\in A\), \(y\in T_xM\), \(\Vert y\Vert _h=\sqrt{h_{\alpha \beta } y^\alpha y^\beta } \le a \sum _\mu \vert y^\mu \vert \). As each component \(x^\mu (t)\) is absolutely continuous, each derivative \(\dot{x}^\alpha \) is integrable and so \(\Vert \dot{x}\Vert _h\) is integrable. The integral

is the Riemannian h-arc length. Observe that by definition causal vectors are not zero so the argument of the integral is positive almost everywhere so the map \(t\mapsto s(t)\) is increasing and absolutely continuous. Its inverse \(s\mapsto t(s)\) is differentiable wherever \(t\mapsto s(t)\) is with \(\dot{s}\ne 0\), in fact \(t'= \dot{s}^{-1}=\Vert \dot{x}\Vert _h^{-1}\) at those points, where a prime denotes differentiation with respect to s. By Sard’s theorem for absolutely continuous functions (Montesinos et al. 2015) and by the Luzin N property of absolutely continuous functions, a.e. in the s-domain the map \(s\mapsto t(s)\) is differentiable and \( \dot{x}(t(s))\in C_{x(t(s))}\). At those points \( x'= \dot{x}/\Vert \dot{x}\Vert _h^{-1}\in C_{x(t(s))}\) so \(\Vert x'\Vert _h=1\) and the map \(s \mapsto x(t(s))\) is really Lipschitz. The discussion shows that by a change of parameter we can pass from absolutely continuous causal curves to Lipschitz causal curves parametrized with respect to h-arc length (see also the discussion in Petersen 2006, Sect. 5.3).

2.4 Local maximization properties of geodesics

The Lorentzian length of a causal AC-curve is

The integral is finite, in fact locally we can find coordinates \(\{x^\mu \}\) and a constant \(a>0\) such that over causal vectors \(\sqrt{-g(v,v)}\le a v^0\), and moreover \({\dot{\sigma }}^0(t)\) belongs to to \(L^1([a,b])\) as \(\sigma (t)\) is absolutely continuous.

The proof of the following result is adapted from Minguzzi (2015b, Theorem 6). For an alternative proof of the first part see Chruściel (2011, Proposition 2.4.5).

Theorem 2.9

Let (M, g) be a spacetime for which g is \(C^{2}\). Let N be a normal neighborhood of \(p\in M\) and let \(\sigma :[0,1]\rightarrow N\) be any future directed causal AC-curve starting from p, then \(\exp ^{-1}(\sigma (s))\) is future directed causal for every \(s>0\), and if \(\exp ^{-1}(\sigma ({\hat{s}}))\) is lightlike then \(\sigma \vert _{[0,\hat{s}]}\) coincides with a future directed lightlike geodesic segment up to parametrizations.

Finally, the Lorentzian length of \(\sigma \) is smaller than that of the (unique) future directed causal geodesic connecting its endpoints, unless its image coincides with that of that geodesic. In this last case the affine parameter of the geodesic is absolutely continuous and increasing with s.

Proof

If q is a point such that \(D^2_p(q)\le 0\), the Lorentzian length of the geodesic \(\gamma \) connecting p to q is:

that is \(D^L_p(q):=(- D^2_p(q))^{1/2}\). Since \(D_p^2\) is \(C^{2}\), \(D^L_p\) is \(C^{2}\) in the region \(D_p^2< 0\).

Suppose that for some \(\tilde{s}\), \( D_p^2(\sigma (\tilde{s}))< 0\). By continuity the same inequality holds in an interval \([\tilde{s},s]\) provided s is sufficiently close to \(\tilde{s}\), which implies that \(P(p,\sigma (s'))\) is causal for \(s'\in [{\tilde{s}},s]\). The function \(D^L(\sigma (s))\) being the composition of a locally Lipschitz and an absolutely continuous function is absolutely continuous over \([\tilde{s},s]\). We have

where \({\hat{P}}:=P/\sqrt{-g_{\sigma (s)}(P,P)}\). In the last inequality we used the reverse Cauchy–Schwarz inequality.

The inequality so obtained proves that once \(\sigma \) enters the region with \(D^2_p<0\) it remains in that region (this is the region of points reachable from p with a timelike geodesic in N) for the function \(D^2_p\) can only decrease.

Now let \(\eta :[-\epsilon ,0] \rightarrow C\), \(\eta (0)=p\), be a small future directed timelike geodesic contained in a convex normal neighborhood of p, \(p\in C\subset N\). For sufficiently small s, \(\sigma (s)\in C\), and the curve obtained concatenating \(\eta \) with \(\sigma \) which connects \(\eta (-\epsilon )\) to \(\sigma (s)\) starts with a timelike geodesic, hence it enters the chronological future of \(\eta (-\epsilon )\), and hence, by the above argument there is a future directed timelike geodesic \(\nu ^{(\epsilon )}\) connecting \(\eta (-\epsilon )\) to \(\sigma (s)\). Letting \(\epsilon \rightarrow 0\), and using the continuity of the exponential map \(\exp \) at \(\sigma (s)\) we infer the existence of a geodesic connecting p to \(\sigma (s)\), which by the continuity of \(g_{\sigma (s)}(v,v)\) at \( T_{\sigma (s)}M\) must be future directed causal. As s is arbitrary we have shown that in a maximal closed interval \([0,b]\subset [0,1]\), \(b>0\), we have \(D^2_p(\sigma (s))\le 0\).

Let us prove that if for \(a\in (0,b]\), \(D^2_p(\sigma (a))=0\) then \(\sigma \vert _{[0,a]}\) is a lightlike geodesic up to parametrizations and hence that \(D^2_p=0\) over [0, a].

Observe that \(D^2_p\) is Lipschitz, thus \(D^2_p(\sigma (s))\) is absolutely continuous

Since on the region \(D^2_p\le 0\), we have \(g_{\sigma (s)}(P(p,\sigma (s)), \sigma '(s))\le 0\) for almost every s (by the reverse Cauchy–Schwarz inequality since \(\sigma '\) is future directed causal almost everywhere), thus we can have \(D^2_p(\sigma (a))=0\) only if \(\sigma '\propto P\) for almost every s in [0, a]. Let us introduce a Euclidean scalar product on \(T_pM\), and associated spherical normal coordinates \((r,\theta _1,\ldots , \theta _{n})\) over N. As this coordinate chart is \(C^1\) related to those of M, \(\sigma \) is still absolutely continuous in this chart. Thus since \(\sigma '\propto \partial _r\) almost everywhere, the angular coordinates cannot change over \(\sigma \), otherwise since \(\theta _i(\sigma (s))\) is the integral of its own derivative one would get that \(\sigma '\) is not radial in a set of non-vanishing measure, a contradiction. Thus \(\sigma \vert _{[0,a]}\) is an integral curve of P, hence a lightlike geodesic issued from p.

From now on let a be the maximum value of s for which \(D^2_p(\sigma (s))=0\).

It remains only to prove that \(b=1\). Suppose not then \(a=b\) otherwise \(D^2_p(b)<0\), which would imply the same inequality also in (b, 1], a contradiction to \(b<1\). Set \(p'=\sigma (b)\) and take a convex normal neighborhood \(C'\ni p'\), \(C'\subset N\). Arguing as above proves that for any sufficiently small \(\delta \), \(p'\) is connected to \(\sigma (b+\delta )\) by a future directed causal geodesic \(\eta : [0,1]\rightarrow C'\). This geodesic cannot be the prolongation of the lightlike geodesic \(\sigma _{[0,b]}\) for we would get \(D_p^2(\sigma (b+\alpha \delta ))\le 0\), \(\alpha \in [0,1]\), a contradiction to the maximality of b. Thus the scalar product \(g_{\eta (t)}(P(p,\eta (t)), \eta '(t))\) is negative for \(t=0\) and hence in a neighborhood of \(t=0\). Now, observe that \(D^2_p\) is \(C^1\), thus \(D^2_p(\eta (t))\) is absolutely continuous and, for sufficiently small t,

As the concatenation of \(\sigma _{\vert _{[0,b]}}\) with \(\eta \) is a causal AC-curve and on it \(D^2_p\) becomes negative at some point, and it remains so, we have at the endpoint \(D^2_p(\sigma (b+\delta ))=D^2_p(\eta (1))<0\). As \(\delta \) is arbitrary we get a contradiction to the maximality of b. The contradiction proves that \(b=1\).

If \(\sigma \) is a lightlike geodesic up to parametrization, then clearly its Lorentzian length vanishes and the inequality \(D_p^L(\sigma (1))\ge l(\sigma )\) is satisfied. Suppose that \(\sigma \) is not a lightlike geodesic up to parametrizations then \(a<1\), and its Lorentzian length is given just by the contribution of \(\sigma _{[a,1]}\). Let \(\tilde{s}\in [a,1]\) so that \(D^2_p(\sigma (\tilde{s}))<0\). By (2.8)

and taking the limit \(\tilde{s}\rightarrow a\) we obtain \(D^L_p(\sigma (1))\ge l(\sigma )\). This proves that \(\sigma \) has a Lorentzian length no larger than that of the geodesic connecting its endpoints.

Now, suppose by contradiction that they have the same Lorentzian length and that \(\sigma \) is not a causal geodesic up to parametrizations. Then necessarily \(a<1\), for otherwise it would be a lightlike geodesic. But then from (2.8), for \(\tilde{s}>a\),

Thus the equality implies that the first inequality is actually an equality, which implies the equality case for almost every \(s\in [\tilde{s}, 1]\) in the reverse Cauchy–Schwarz inequality used to deal with \(g_{\sigma (s)}(P(p,\sigma (s)),\sigma '(s))\) and hence, by the arbitrariness of \(\tilde{s}\), \(\sigma '\propto P\) for almost every \(s\in [a,1]\). Introducing again spherical normal coordinates and arguing as above proves that the image of \(\sigma \vert _{[a,1]}\) is an integral curve of P (and hence the prolongation of \(\sigma \vert _{[0,a]}\) if \(a\ne 0\)), thus it is the image of a geodesic.

Finally, suppose that the image of \(\sigma \) coincides with that of a causal geodesic \(\eta \). Since the coordinates of the spherical normal chart are Lipschitz functions, the composition r(s) is absolutely continuous. By definition r is an affine parameter over the geodesic \(\eta \). The map r(s) is necessarily increasing, for if \(r(s_2)\le r(s_1)\) for \(s_1<s_2\), then we would have \(r'\le 0\) in a subset of measure different from zero on \([s_1,s_2]\), which would imply that \(\frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}s } \sigma =(\frac{\mathrm{d}}{\mathrm{d}r } \eta ) r'\) is not future directed causal in a set of measure different from zero, a contradiction to the definition of future directed causal AC-curve. \(\square \)

Corollary 2.10

Let N be a normal neighborhood of p. Then for \(v\in \exp _p^{-1} N\subset T_pM\):

- 1.

\(\exp _p \!v \in J_N^+(p)\) iff v is future directed causal or zero,

- 2.