Abstract

There is growing evidence that positive psychology interventions (PPIs) are effective in enhancing mental well-being and reducing depressive symptoms. However, there is a knowledge gap regarding the motives of people to seek such PPIs. This study qualitatively identifies help-seeking motives and quantitatively examines which motives relate to client satisfaction, adherence and an impact on mental well-being, anxiety and depressive symptoms. We analyzed 123 introductory emails of people with suboptimal levels of mental well-being who assigned to a comprehensive 9-week PPI with email support, of which its efficacy was investigated in a randomized controlled trial. Results showed that 49% mentioned mainly suffering-related motives (i.e. distress and stressful events/circumstances) and 51% mentioned mainly growth-related motives (i.e. mental well-being and developing resources). Hardly any motive was significantly related to beneficial outcomes, albeit developing resources and suffering were positively—though weak—correlated with adherence. The present study indicates that this PPI was effective for a broad audience, namely for those with suffering-related and with growth-related motives. This finding underscores the great relevance of PPIs to reach people who might be at risk for future mental disorders who otherwise do not seek help.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the last decades, a growing number of interventions have been developed to promote mental well-being in different non-clinical and clinical populations. The concept of mental well-being dates back from ancient times (Aristotle 1925), although the current progress in empirical evidence and interest for mental well-being in clinical and counseling practice has emerged since the foundation of the positive psychology movement in the beginning of this century (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000). The precise conceptualization of mental well-being is rather complex because there are many theories using different terminology (Huta and Waterman 2013). However, it is now widely recognized that mental well-being comprises subjective well-being or emotional well-being (i.e. feelings of happiness, life-satisfaction and a positive-negative affect balance), psychological well-being (e.g. self-acceptance, personal growth and purpose in life) and social well-being (e.g. social contribution and social coherence; Diener 1984; Diener and Ryan 2009; Keyes 1998; Ryff 1989). In other words, subjective well-being mirrors ‘feeling good’ (hedonia), while psychological and social well-being refer to ‘living well’ (eudaimonia) (Deci and Ryan 2006; Ryan and Deci 2001).

The growing number of well-being interventions usually target aspects of positive psychology such as positive emotions, gratitude, self-compassion, personal growth and positive relations with others. The primary aim of these so called positive psychology interventions (PPIs) is to increase positive feelings, cognitions and behaviors (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000) albeit the underlying aim is to reduce psychological distress and to prevent the onset of mental disorders. Despite growing evidence about the efficacy of PPI’s on both enhancing mental well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms (e.g. Layous and Lyubomirsky 2012; Bolier et al. 2013b; Weiss et al. 2016; Sin and Lyubomirsky 2009), mainstream counseling and clinical practice still primarily use cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT)-based programs for reducing psychological distress. Research has shown that most people with symptoms of distress do not seek professional help for various reasons (Andrews et al. 2001; Mojtabai et al. 2002). For example, people prefer to self-manage distress (Thompson et al. 2004), have a lack of willingness to self-disclose personal thoughts and feelings (Vogel and Wester 2003), experience stigma associated with mental health disorders (Vogel et al. 2007a) or believe that they do not have a (serious) mental health problem (Mojtabai et al. 2002). Not seeking help may lead to a further decrease in quality of life and a further increase in suffering.

Positive psychology-based interventions have the potential to reach other types of clients than traditional mental health services, for instance, because they might be less associated with stigma or with having a mental disorder. PPIs could attract clients who display a broad range of mental health problems and, therefore, seem to fit seamlessly on counseling practice and public mental health (Lent 2004). An understudied topic is, however, why people seek positive counseling and what implications such help-seeking motives have for participants’ engagement in the intervention and—in the end—for the efficacy of the intervention.

Positive Psychology Interventions and its Users

Thus far, the majority of scientific studies have focused on whether well-being enhancing interventions are effective (Layous and Lyubomirsky 2012; Bolier et al. 2013b; Weiss et al. 2016; Sin and Lyubomirsky 2009), but not whether they attract a different audience. Parks et al. (2012) were the first to examine the question ‘who are likely users of PPIs?’. They conducted a cross-sectional study with 912 ‘online happiness seekers’—people who were interested to participate in a one-week web-based positive psychology exercise. They received questionnaires to assess depressive symptoms and subjective well-being. Cluster analyses revealed two subgroups: (1) people who display severe depressive symptoms in combination with below average life-satisfaction scores (49.5% of the total sample) and (2) people who display average depressive symptoms and average life-satisfaction scores (50.5% of the total sample; Parks et al. 2012). These two different groups of ‘distressed’ versus ‘non-distressed’ people have recently been replicated through cluster analyses in two large samples of people who participated in a 1 or 3-week intervention of online positive psychology exercises (Sergeant and Mongrain 2015). This study also revealed that the distressed cluster showed a larger decrease in depressive symptoms and a larger increase in life-satisfaction after completing the exercises than the non-distressed cluster.

These studies showed that PPIs seem to attract a broad target population, but only used quantitatively measured psychological constructs. To gain more insight into the reasons why people participate in a PPI, qualitative research is also needed. To our knowledge, such qualitative research has not been done before. In addition, the participants in both of the aforementioned studies were instructed to practice only one particular positive psychology exercise during the study period (Parks et al. 2012; Sergeant and Mongrain 2015). However, more enduring effects on mental well-being and depression can be expected for comprehensive programs, especially when guided by a counselor (Andersson and Cuijpers 2009; Fledderus et al. 2012; Pots et al. 2016).

Comprehensive PPIs are often based on a theoretical framework and typically include psycho-education, numerous positive psychology-based exercises and involvement of a therapist or counselor, although a precise definition of a comprehensive or multicomponent PPI is currently lacking. Examples of effective comprehensive well-being programs are the 14-session Positive Psychotherapy program (Rashid 2014; Seligman et al. 2006) and a 10-session group PPI (Chaves et al. 2016) for clinical populations, the 6-week Working for Wellness group program for employees (Page and Vella-Brodrick 2012), and the 9-week This is Your Life self-help program for the general public (Schotanus-Dijkstra et al. 2015; Schotanus-Dijkstra et al. 2017a). Such intensive comprehensive programs require persistence to continue practice and a willingness to invest time. Hence, people who seek such programs need to have a certain amount of motivation and need for help. However, the (qualitative) motives of users of comprehensive positive psychology-based programs and their relationship with treatment engagement and impact have not yet been studied. The current study will address these gaps in the literature.

Present Study

The current study is based on a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of an email guided comprehensive PPI for people with low or moderate levels of mental well-being recruited in the general population (Schotanus-Dijkstra et al. 2017a; Schotanus-Dijkstra et al. 2015). The aim of this study is to (1) qualitatively identify the motives of a self-selected sample of people who were interested in participating in the comprehensive self-help intervention, of which the motives were derived from introductory emails to their counselors, (2) to quantitatively examine which motives relate to client satisfaction and adherence to the program and (3) to quantitatively examine which motives relate to change scores in mental well-being, anxiety and depressive symptoms at 3 and 6 months after baseline. In line with the studies of Parks et al. (2012) and of Sergeant and Mongrain (2015), we expected to find motives related to suffering as well as motives related to mental well-being. We expected that the latter type of motives might significantly relate to client satisfaction and adherence because the aim of a PPI fits well with the desire to be happier and more meaningful. On the other hand, the former motives might significantly relate to more beneficial mental health outcomes because the people with distress-related motives might suffer more than people with hedonic or eudaimonic motives and thereby have more room to grow by participating in a PPI.

Method

Design

Both qualitative and quantitative data were collected and analyzed of an intervention group who participated in a RCT about the efficacy of a comprehensive PPI called This is Your Life, aimed at enhancing mental well-being and flourishing mental health (Schotanus-Dijkstra et al. 2017a, b). In the current study, the introductory emails of participants to their personal counselor were qualitatively analyzed using content analysis to identify motives of people to participate in this comprehensive PPI. In addition, the main motives as revealed by the content analysis were quantitatively related to client satisfaction and adherence to the program, and to improvement in mental well-being, anxiety and depressive symptoms. Assessments took place at baseline (T0), at post-intervention, approximately 3 months after baseline (T1) and at follow-up, 6 months after baseline (T2). The RCT-study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Twente (no. 13212) and registered in The Netherlands Trial Register (NTR4297). All participants gave online informed consent before participating in the study, including informed consent regarding the use of the email messages for scientific purposes.

Intervention

This is Your Life is a self-help book and consists of eight chapters covering six key components of mental well-being: positive emotion, discovering and using strengths, optimism and hope, self-compassion, resilience and positive relations. Each chapter contains psycho-education and a wide variety of positive psychology-based exercises such as ‘the three good things’ (savor the things that went well that day), ‘imagine you best possible self’ (visualize yourself in the personal, relational and professional domain); and ‘active-constructive responding’ (positively and actively respond to good news shared by others). The chapters were spread out over 9 weeks in a time-schedule and the participants were encouraged to practice at least two of the recommended exercises per week (see for more details our prior publications: Schotanus-Dijkstra et al. 2015; Schotanus-Dijkstra et al. 2017a). Participants could spend a maximum of 12 weeks on the program (taken holidays and personal circumstances into account) and received weekly email support of a personal counselor during the weeks they worked on the program. The counselors were masters students in the Department of Psychology, Health and Technology at the University of Twente. They received weekly supervision and were instructed to give tailored feedback about to process and progression of the participants.

Procedure

Participants were recruited for the RCT in The Netherlands by advertisements placed in national newspapers and in an online newsletter of a popular psychology magazine in January 2014. Recruitment messages were positively framed: (1) ‘Get the best out of yourself and improve your resilience and well-being with a free self-help course’ and (2) ‘Become happy and stay happy? Improve your resilience and well-being with a free self-help course (Schotanus-Dijkstra et al. 2015). Eligible participants were self-selected adults of 18 years or older who were motivated to work on their well-being and resilience for approximately 4 h per week. Eligible participants had to have a valid email address and sufficient Internet connection for the email counseling and for filling out the online questionnaires. After registration, participants who gave online informed consent received a screening questionnaire to assess the level of mental well-being and the level of anxiety and depressive symptoms. Participants were excluded when they were classified as having flourishing mental health (i.e. combination of high levels of hedonic well-being and high levels of eudaimonic well-being) as measured with the Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) and using the cut-off values for flourishing as proposed by Keyes (Keyes 2006; Keyes et al. 2008). Participants were also excluded when they scored above 10 on either the anxiety or depression subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), indicating moderate or severe symptoms (Zigmond and Snaith 1983; Spinhoven et al. 1997). The recruitment strategy attracted many participants in a short amount of time, resulting in 518 participants who assigned to the program during 3 weeks recruitment. After screening, the total sample of the RCT-study consisted of 275 participants (Schotanus-Dijkstra et al. 2017a). 137 participants were randomly assigned to the intervention group who received the self-help book This is Your Life with email support from a counselor. The other 138 participants were randomly assigned to the wait-list control group who received the self-help book (without email support) after 6 months.

On February 122,014, all participants in the intervention group received an email from their personal counselor. The five masters students each guided 25 participants. The remaining participants were guided by the first author. In this first email, participants were warmly thanked for their participation in the study about resilience and well-being. The novice counselor introduced herself briefly (‘My name is X. I am currently in the last phase of my Psychology study at the University of Twente. I am educated in positive psychology among other things and I hope that I can guide you in a good way’), mentioned that the participant could start reading the first chapter of the book, and explained the procedure of the email support. The introduction email ended with the following question: ‘Can you already send me a brief email next Sunday or Monday wherein you introduce yourself and write what you hope to achieve with this course?’ The answer to this question in the first email from each participant was the basis for the content analysis.

Participants

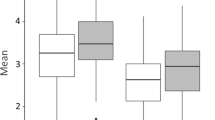

The current sample consisted of 123 participants from the intervention group who had sent an introductory email to their personal counselor. The average age of the current sample was 48.6 years (SD = 11.04). They were mainly female (87.8%), higher educated (73.2%), married (43.1%), in paid employment (67.5%) and of Dutch nationality (89.4%). These characteristics are compatible with the total intervention group (n = 137) and the total sample (n = 275) of the RCT-study (Schotanus-Dijkstra et al. 2017a). In addition, the mean number of modules that participants spent at least some time on was 6.6 (SD = 2.17). Also, client satisfaction was high with a mean score of 3.1 (SD = .60) on a scale from 1 to 4 and the level of mental well-being was moderate (M = 2.58, SD = .63) which is slightly lower than the population norm (Lamers et al. 2011). Due to the inclusion criteria, the level of anxiety (M = 7.1, SD = 2.42) and depression (M = 5.7, SD = 2.51) were low but approximately 2 points higher than the population norm (Spinhoven et al. 1997). All of the excluded participants (n = 14) had sent an email, but these emails did not contain any information of introducing themselves. Most of these participants just wanted to inform the counselor that they resigned from the program (n = 9). On average, these 14 excluded messages consisted of 58 words (18–141 words).

Qualitative Data

Coding Scheme

All email correspondence was anonymously saved in word documents per participant number, removing the opening (‘Dear X’) and closing (‘Greetings, X’) sentences. Other information that is traceable to the person was also removed, such as their own or family-member names, or their place of residence. The number of words from each introductory email was counted. Then, all unnecessary demographic information and technical issues were removed and long citations were shortened to obtain feasible fragments for coding. Both direct motives (‘My goal for this course is to …’) and indirect motives (personal stories about their life or current situation) for participating in the intervention were coded, which from now on is referred to as ‘motives’. From each participant, this adjusted introductory email was saved and uploaded as separate file in the software package Atlas.ti, version 7.

Qualitative Analyses

A conventional coding approach was used, meaning that the coding scheme was derived from the text (open or inductive coding) rather than theory (Hsieh and Shannon 2005). Each email could contain multiple codes, but each code could only be assigned once to an introductory email of one participant. The first two authors independently read and coded 16 introductory emails to obtain a draft version of the coding scheme. This draft version was tested on 8 new introductory emails by independent coding, adjusted and then tested on another 8 introductory emails. Differences between both raters were discussed until consensus was reached. This process was repeated until no new codes were found (saturation). The final coding scheme is presented in Table 1. Secondly, two broad codes were further refined in separate coding schemes: ‘distress aspects’ (Table 2) and ‘mental well-being aspects’ (Table 3). At the end of the coding procedure of each email, we attempted to classify the overall impression of the participant into (1) only suffering, (2) predominantly suffering, (3) predominantly searching for growth, and (4) only searching for growth. The final schemes were used by the first author to code all introductory emails. 35% of these emails (n = 43) were also coded by the second author to test the inter-rater reliability. Cohen’s kappa varied between .68 for the code overall impression and 1.00 for the codes suffering and mental well-being, indicating substantial to perfect kappa.

Quantitative Data

Measures

Client satisfaction was measured with the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-short form (CSQ-8) (Attkisson and Zwick 1982) which was completed at 3 months (T1). Answers are given on a 4-point scale with different answer options. Higher total mean scores indicate higher satisfaction with the offered intervention.

The number of sent emails and the self-reported number of completed modules were used as indicators of engagement (adherence) to the program. The latter was measured at T1 by asking the participants: ‘How much time did you spent on module …[module 1-8]?’ Answers were given on a 5 point scale for each module, that ranged from 1 (no time spent) to 5 (spent a lot of time). When participants spent no time (1) or little time (2) on a module, this was coded as not-completed.

We used the MHC-SF to measure mental well-being as defined by Keyes et al. (2008), wherein emotional well-being, social well-being and psychological well-being are integrated. Each of the 14-items were rated on a scale from 0 (never) to 5 ((almost) always) which slightly differs from its original scale that runs from 0 (never) to 5 (every day). Higher total mean scores indicate higher levels of mental well-being. The internal consistency at baseline was good (α = .88), in agreement with prior validation studies (Keyes et al. 2008; Lamers et al. 2011).

Anxiety and depressive symptoms were only measured at baseline and at 6 months, with the subscales of the HADS, the HADS-A and HADS-D respectively (Spinhoven et al. 1997; Zigmond and Snaith 1983). Each subscale consists of 7 items with scores ranging from 0 to 3. Higher total summed scores (0–21) indicate higher symptom levels. The internal consistency was good (α = .76 for both subscales), in agreement with prior validation studies (Bjelland et al. 2002; Spinhoven et al. 1997).

Quantitative Analyses

Missing data on the T1 and T2 outcome measures of the intervention group were imputed using the estimation maximization (EM) algorithm. We calculated the change scores per time-point. For mental well-being, these change scores were calculated by subtracting the T0 score from the T1 score (post-test) and subtracting the T0 score from the T2 score (follow-up). A positive change score on mental well-being means an increase in mental well-being over time. Anxiety and depression were not measured at T1, so for these outcomes the change scores were calculated by subtracting the T0 score from the T2 score. A negative change score on anxiety and depressive symptoms means a decrease in these symptoms. Each main code derived from the qualitative analysis was correlated with (1) the number of words of the introductory email, (2) the T1 scores of client satisfaction and adherence, and (3) the change scores in mental well-being, anxiety and depression using Spearman’s rho (rs). The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL).

Results

The length of the introductory emails of the 123 participants varied greatly, from 58 words to 999 words (M = 280, SD = 175). Participants’ motives could be divided into three overarching motives: suffering, desire for growth and other (Table 1). The first category, suffering, included negative or distressed feelings as well as stressful events or circumstances. Distress feelings contained being unhappy, experiencing negative or depressed feelings, but also having low self-esteem, being self-critical or feeling insecure (Table 2). Our analyses revealed that a large number of participants (89%) mentioned at least some suffering in their introductory emails. Sometimes the distress motive was highly related to stressful events or circumstances: ‘The reason I am interested in your course is that more than a year ago, I had a burn-out after being employed for 40 years. In consultation with my employer I have decided to quit my job.’. Most frequent subcategories of suffering were feeling unhappy, negative or depressed (42%), stress from work mainly due to a (threatening) of job loss (37%), family-related stress such as the loss of a loved one, relationship problems or taking care of a family member (28%), feeling worried, restless or anxious (24%) and feeling tired or not in balance (20%).

The second category, growth, consisted of motives related to a wish or desire for improving mental well-being aspects and developing resources (see Table 1). Developing resources were also considered as growth because such factors might be beneficial for maintaining or enhancing mental well-being. An overview of mental well-being aspects can be found in Table 3 and shows that these motives can vary widely, from more general (desire to feel happier or improving ‘mental well-being and resilience’) to more specific (give life new meaning or improving relationships). A large percentage of our participants mentioned one or more growth-related motives (92%) in their introductory email, of which the following subcategories were most frequent: having one or more hobbies (30%), a desire to be more sensitive to positive things in life (37%), desire for being more mindful, relaxed and self-compassionate (36%), desire to improve their resilience to better cope with (future) adversity (24%) and being a positive or resilient person (23%).

The last category, other, contains prior experiences with treatment (‘I have worked through the first book Living to the full in a group’), course-related motives (‘I find it interesting to see whether the approach of positive psychology and the exercises can help me to stay more steady and more positive’) and (professional) curiosity (‘Personally but also from my profession as a return-to-work consultant I am very interested in the topic of developing resilience’).

Overall Impression

Based upon the raters’ overall impression, participants were also divided into (1) only suffering (17%), (2) predominantly suffering (32%), (3) predominantly searching for growth (38%) or (4) only searching for growth (13%). Notably, it was sometimes difficult to determine the overall impression when both suffering and searching for growth motives were described in the email. Cohen’s kappa for this category was lowest (.68), yet sufficient.

Writing more words in the introductory email was significantly correlated with the overall impression as (predominantly) suffering (rs = −.27) and with its corresponding categories (suffering, feelings of distress and stressful events or circumstances, rs between .19 and .44). The number of words was also significantly and positively associated with developing resources (rs = .36) and other motives (rs = .34).

Who Benefited Most?

Nor the overall impression of the introductory emails, neither the main motives were significantly associated with client satisfaction or adherence to the program. In addition, none of the motives were significantly related to changes in mental well-being or anxiety or depressive symptoms between baseline and 3 or 6 months follow-up (Table 4). The only exception was found for the number of completed modules, which was positively correlated with more mentioning of developing resources and more suffering. However, both yielded small correlations of rs = .20 and .19 respectively. Overall, the results indicate that the intervention was effective for a group of participants with a great variety of motives.

Discussion

In this paper we explored the motives of users participating in a comprehensive positive psychology self-help intervention with email support. The content analysis of introductory emails sent by people with low or moderate levels of mental well-being to their personal counselors showed motives related to (1) suffering from feelings of distress (76%, e.g. negative mood, worrying, having low self-esteem) and suffering from stress related events or circumstances (61%, e.g. loss of work or relationship, taking care of a relative), (2) a desire to grow on mental well-being aspects (82%, e.g. being more sensitive to positive things in life, improving resilience to better cope with future adversity, being more self-compassionate) and having one or more developing resources (55% e.g. hobbies, being a resilient or positive person), and (3) other motives (46%, e.g. the positive character of the program, curiosity or positive experiences with prior treatments). Based on these different types of motives, we also classified people in one of four groups: people who mentioned predominantly growth motives (38%), people who mentioned predominantly suffering motives (32%), people who mentioned only suffering motives (17%) and people who mentioned only growth motives (13%). None of these subgroups were significantly more engaged in the intervention program or benefited more from it compared to the other groups. These findings suggest that a comprehensive PPI can be beneficial for a diverse group of ‘happiness-seekers’.

Suffering Versus Growth Motives

In accordance with our hypothesis, the current study revealed both suffering and growth motives. This seems also in agreement with a review of Lent (2004). He has argued that people who self-initiate counseling may have a hedonic well-being oriented help-seeking motive (‘desire for symptom relief and restoration of life-satisfaction’) or a eudaimonic well-being oriented motive (‘desire for growth, learning, change or understanding’). The former seems to mirror our suffering and stress-related motives, while the latter seems to mirror our growth motives. However, we interpreted the hedonic well-being motives somewhat differently while coding the emails. Most people did not seem to describe a clear desire to restore life-satisfaction because they formulated hedonic related motives more in positive developmental goals (‘I want to have happier moments’, ‘I want to be more satisfied about the way I work’) rather than an (indirect) motive for symptom relief (‘I feel unhappy’). These findings indicate that suffering and growth motives seems distinguishable but do overlap on the boundaries of each definition, at least in written text wherein no non-verbal cues are present and some interpretation depends on the researcher’s perspective.

Lent (2004) also believes that growth motives are probably not the initial motives with which people come into counseling practice, but may emerge when treatment is progressing. Yet, we found such motives already in the introductory emails which were sent before the start of the intervention. This might have been a consequence of the positive nature of the intervention or the positive formulated recruitment message. This might indicate that we were able to reach a broader target group: not merely the people who would eventually seek treatment because of increased suffering, but also those who want to grow to prevent symptoms of distress in the future. However, our study could only use data of those people who had participated in This is Your Life. Future research should gain more insight in whether PPIs are indeed able to reach a broader target group in counseling practice compared to other programs based on mindfulness or CBT. Such studies can help answer for whom a PPI is indicated and for whom contraindicated (Dobkin et al. 2012).

In fact, we found no support for our hypothesis that people who participated in a PPI because of growth-related motives were more likely to be satisfied with the program or adhered to it. We also found no relation between suffering-related motives and health outcomes. This means that we found that none of the motives were associated with better or worse treatment outcomes. The exception was that we found that participants who mentioned developing resources in their introductory email were more likely to complete a larger number of modules. This indicates that it may be beneficial for treatment adherence that counselors develop a sensitivity for gaining insight and utilize resources of their clients to keep them engaged in therapy.

Help-Seeking Process

Various studies have shown that many people do not seek psychological treatment for symptoms of distress (Andrews et al. 2001; Mojtabai et al. 2002). The help-seeking process is complex and the final decision for seeking help (or not) will depend on the interplay between ‘approach’ and ‘avoidance’ factors (Vogel et al. 2007b; Vogel and Wester 2003). The current study focused on the reasons why people had assigned to this PPI (approach factors) and found somewhat similar reasons as have been previously found for seeking mental health services in general. For instance, the level of suffering from distress and prior positive experiences with treatment seem important determinants of help-seeking behavior (Mojtabai et al. 2002; Vogel et al. 2007a, b), which were also present in the current study. Concern about self-disclosure in counseling, and especially concern about emotional self-disclosure, have been found to be among the most important reasons not to seek help from a counselor (Vogel and Wester 2003). Interestingly, the people in the current study were quite open in their first email to their counselor, suggesting that we mainly recruited people who felt comfortable in self-disclosing personal information, including one’s emotions. On the other hand, it could also be that the anonymous, online counseling had facilitated openness.

Furthermore, almost all of the identified subcategories of distress in the current study (Table 2) were also present in a list of 50 most frequently mentioned characteristics of a typical person (prototype) who seek help from a psychologist, as has been described by students (Hammer and Vogel 2013). In contrast to our findings, this list consists of mainly negative characteristics such as being stressed, unhappy, worried, indecisive, lonely or having low self-esteem, while our study also revealed different growth motives and developing resources. For example, people mentioned that they wanted to change, develop and know themselves better, improve their resilience and to be more mindful and self-compassionate. To our knowledge, such growth motives for seeking treatment have not been systematically described in prior research. Our findings suggest that a PPI may succeed in reaching a broader group of people, although more studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this study included the large sample size for RCT studies, the use of both qualitative and quantitative data and the broad and open question to participants about a personal introduction of themselves and their goals for the program, which seems to mirror a typical starting question in (online) counseling practice. In addition, the sample of mainly higher educated and middle-aged women seems a realistic target population of early interventions in public mental health and counseling practice because of our open recruitment approach in the general population. These sample characteristics are also in line with prior research (e.g. Parks et al. 2012; Bolier et al. 2013a; Gander et al. 2012). For future implementation, it is important to realize that a self-help book requires a certain level of reading ability. Also, the counseling via email required sufficient writing skills as well as the ability to give words to emotional feelings (Barak et al. 2009; Richards and Vigano 2013). When researchers or practitioners want to reach less educated groups, more simplistic strategies are needed to reach these people through adjustment of the content and delivery of the intervention as well as in the recruitment strategy. In light of this, it seems important to examine the motives of people to participate in scientific research in general as well. For example, financial compensation was not an important motive of cardiac patients to participate in research but this factor might be important for less educated groups of people (Soule et al. 2016).

An important limitation of our study was that the frequencies of the motives derived from the content analysis, as well as its correlations with client satisfaction, adherence and treatment outcomes should be interpreted with some care. We found it sometimes difficult to make a distinction between subcategories within the main category and between the overall impression categories. The interrater reliability was adequate but not optimal, although discrepancies were solved by discussion after the calculation of kappa. Nevertheless, we recommend researchers to use both an open question about people’s motives as well as closed questions to indicate one or more help-seeking motives at screening or after the first (online) counseling session. The categories of motives derived from our content analysis can be used to design the answer categories of closed questions.

Another limitation is that we could only examine the motives of the people who indeed participated in the intervention. Also, the sample was self-selected, consisted of mainly higher-educated women and we decided a priori to exclude people with moderate or severe anxiety and depressive symptoms. This latter decision has reduced variability in participants. More research is needed using a more heterogeneous group, for example to test whether similar motives are found for people with more severe mental health complaints. It would also be interesting to examine whether PPIs attract a broader target population than usual care: who would choose a more traditional CBT-based intervention and who would choose a mindfulness or PPI-based intervention? Why? Furthermore, motives to seek such help as well as not to seek such help should be investigated.

A final limitation is that the participants’ motives might have been colored a bit by the fact that they have written the introductory emails after they have received the self-help book. Also, the self-selected sample and the written motives of these participants may have been influenced by the wordings used in the ad wherein people were recruited (i.e. improve resilience and well-being; become happy and stay happy). Some participants seemed to echo these recruitment messages, of which some persons mentioned this explicitly: ‘What I hope to achieve is what the title harbors: that my mental resilience will increase and thereby also my well-being’.

Practical Implications and Conclusion

Our study showed that the comprehensive PPI attracted a heterogeneous group of both people who are suffering as well as people who have a desire for growth. Moreover, the intervention was equally effective for both groups. This is important as it suggests that comprehensive PPIs have the potential to reach a larger group than traditional therapies. First, people who suffer, but who reject help because of stigma (Vogel et al. 2007a), may be willing to accept this form of help. Second, people who do not suffer may use this type of help to increase their resilience and mental well-being, and prevent future psychiatric morbidity (Schotanus-Dijkstra et al. 2017c; Keyes et al. 2010; Schotanus-Dijkstra et al. 2017c). Therefore, our study is of importance from a public health point of view as well as for counseling practice. An interesting direction for future research might concern who prefer PPI-based interventions and who prefer CBT-based of mindfulness-based interventions, and whether preference for certain types of interventions is related to better mental health outcomes. In this regard it is interesting to note that there are some tentative indications that PPIs and CBT programs work equally well in decreasing depressive symptoms (Chaves et al. 2016; Parks and Szanto 2013).

Another direction for future research may lie in automatic text coding, which is expanding in the literature. Our study consisted of 123 emails which was a good amount to handle by human coding. However, email support has previously been added to other types of psychological interventions as well (Fledderus et al. 2012; Pots et al. 2016; Paxling et al. 2013; Svartvatten et al. 2015; Holländare et al. 2016). To be able to compare email counseling in different interventions and/or different study populations, automatic text coding of such large amounts of text data might be beneficial. Different text processing methods exist, such as the software program Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC), the latent Dirichlet allocation technique (LDA) (Carpenter et al. 2016) and word clouds analysis (McNaught and Lam 2010). However, these methods or programs only detect single words rather than its context (Tausczik and Pennebaker 2010). This might be a problem in the type of study that we did because the word ‘happy’ would be coded as a positive emotion in both of the following sentences: ‘What I want to achieve is to be happier’ and ‘though there are days that you do not feel happy because of various circumstances’. We interpreted the former as a desire to be more positive in life and the latter as feeling unhappy, negative or depressed mood. Developing systems to detect emotional language within its context seems a challenge for future researchers.

To conclude, our study suggests that people who described only or predominantly growth motives engaged and benefited just as much from the early intervention as people who described only or predominantly suffering motives. More importantly, we did not find indications that certain subgroups of people got worse from working on improving positive emotions, strengths, optimism, self-compassion, resilience and positive relations. The current study provides further support for the notion that PPIs can reach a large and broad target group and might be of great importance for public mental health and counseling practice to prevent the onset of symptoms of distress or a worsening of complaints.

References

Andersson, G., & Cuijpers, P. (2009). Internet-based and other computerized psychological treatments for adult depression: A meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 38(4), 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506070903318960.

Andrews, G., Issakidis, C., & Carter, G. (2001). Shortfall in mental health service utilisation. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 179(5), 417–425.

Aristotle. (1925). Nicomachean Ethics (W. D. Ross, Trans.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Attkisson, C. C., & Zwick, R. (1982). The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Evaluation and Program Planning, 5(3), 233–237.

Barak, A., Klein, B., & Proudfoot, J. G. (2009). Defining internet-supported therapeutic interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 38(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-009-9130-7.

Bjelland, I., Dahl, A. A., Haug, T. T., & Neckelmann, D. (2002). The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale: An updated literature review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 52(2), 69–77.

Bolier, L., Haverman, M., Kramer, J., Westerhof, G. J., Riper, H., Walburg, J. A., et al. (2013a). An internet-based intervention to promote mental fitness for mildly depressed adults: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 15(9), e200. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2603.

Bolier, L., Haverman, M., Westerhof, G. J., Riper, H., Smit, F., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2013b). Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health, 13, 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-119.

Carpenter, J., Crutchley, P., Zilca, D. R., Schwartz, A. H., Smith, K. L., Cobb, M. A., et al. (2016). Seeing the ?Big? Picture: Big data methods for exploring relationships between usage, language, and outcome in internet intervention data. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(8), e241. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.5725.

Chaves, C., Lopez-Gomez, I., Hervas, G., & Vazquez, C. (2016). A comparative study on the efficacy of a positive psychology intervention and a cognitive behavioral therapy for clinical depression. [journal article]. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-016-9778-9.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2006). Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: An introduction. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542.

Diener, E., & Ryan, K. (2009). Subjective well-being: A general overview. South Africa Journal of Psychology, 39(4), 391–406.

Dobkin, P. L., Irving, J. A., & Amar, S. (2012). For whom may participation in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program be contraindicated? Mindfulness, 3(1), 44–50.

Fledderus, M., Bohlmeijer, E. T., Pieterse, M. E., & Schreurs, K. M. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy as guided self-help for psychological distress and positive mental health: A randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 42(3), 485–495. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711001206.

Gander, F., Proyer, R. T., Ruch, W., & Wyss, T. (2012). Strength-based positive interventions: Further evidence for their potential in enhancing well-being and alleviating depression. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(4), 1241–1259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9380-0.

Hammer, J. H., & Vogel, D. L. (2013). Assessing the utility of the willingness/prototype model in predicting help-seeking decisions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(1), 83.

Holländare, F., Gustafsson, S. A., Berglind, M., Grape, F., Carlbring, P., Andersson, G., et al. (2016). Therapist behaviours in internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy (ICBT) for depressive symptoms. Internet Interventions, 3, 1–7 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2015.11.002.

Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687.

Huta, V., & Waterman, A. S. (2013). Eudaimonia and its distinction from Hedonia: Developing a classification and terminology for understanding conceptual and operational definitions. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(6), 1425–1456. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9485-0.

Keyes, C. L. M. (1998). Social well-being. Social Psychology Quarterly, 121–140.

Keyes, C. L. (2006). Mental health in adolescence: Is America's youth flourishing? The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 76(3), 395–402. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.76.3.395.

Keyes, C. L., Wissing, M., Potgieter, J. P., Temane, M., Kruger, A., & van Rooy, S. (2008). Evaluation of the mental health continuum-short form (MHC-SF) in setswana-speaking south Africans. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 15(3), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.572.

Keyes, C. L. M., Dhingra, S. S., & Simoes, E. J. (2010). Change in level of positive mental health as a predictor of future risk of mental illness. American Journal of Public Health, 100(12), 2366–2371. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.192245.

Lamers, S. M. A., Westerhof, G. J., Bohlmeijer, E. T., ten Klooster, P. M., & Keyes, C. L. M. (2011). Evaluating the psychometric properties of the mental health continuum-short form (MHC-SF). Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(1), 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20741.

Layous, K., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2012). The how, why, what, when, and who of happiness: Mechanisms underlying the success of positive activity interventions. In J. Gruber & J. T. Moskowitz (Eds.), Positive emotion: Integrating the light sides and dark sides. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lent, R. W. (2004). Toward a unifying theoretical and practical perspective on well-being and psychosocial adjustment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(4), 482.

McNaught, C., & Lam, P. (2010). Using Wordle as a supplementary research tool. The Qualitative Report, 15(3), 630.

Mojtabai, R., Olfson, M., & Mechanic, D. (2002). Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(1), 77–84.

Page, K. M., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2012). The working for wellness program: RCT of an employee well-being intervention. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14(3), 1007–1031. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9366-y.

Parks, A. C., & Szanto, R. K. (2013). Assessing the efficacy and effectiveness of a positive psychology-based self-help book. Terapia Psicológica, 31, 141–149.

Parks, A. C., Della Porta, M. D., Pierce, R. S., Zilca, R., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2012). Pursuing happiness in everyday life: The characteristics and behaviors of online happiness seekers. Emotion, 12(6), 1222–1234. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028587.

Paxling, B., Lundgren, S., Norman, A., Almlov, J., Carlbring, P., Cuijpers, P., et al. (2013). Therapist behaviours in internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy: Analyses of e-mail correspondence in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 41(3), 280–289. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465812000240.

Pots, W. T., Fledderus, M., Meulenbeek, P. A., Ten Klooster, P. M., Schreurs, K. M., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy as a web-based intervention for depressive symptoms: Randomised controlled trial. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 208(1), 69–77. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.146068.

Rashid, T. (2014). Positive psychotherapy: A strength-based approach. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(1), 25–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.920411.

Richards, D., & Vigano, N. (2013). Online counseling: A narrative and critical review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(9), 994–1011. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21974.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069.

Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Drossaert, C. H. C., Pieterse, M. E., Walburg, J. A., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2015). Efficacy of a multicomponent positive psychology self-help intervention: Study protocol of a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, Research Protocols, 4(3), e105. https://doi.org/10.2196/resprot.4162.

Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., ten Have, M., Lamers, S. M., de Graaf, R., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2016). The longitudinal relationship between flourishing mental health and incident mood, anxiety and substance use disorders. The European Journal of Public Health, ckw202.

Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Drossaert, C. H. C., Pieterse, M. E., Boon, B., Walburg, J. A., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2017a). An early intervention to promote well-being and flourishing and reduce anxiety and depression: A randomized controlled trial. Internet Interventions, 9, 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2017.04.002.

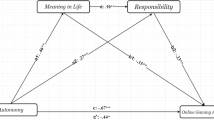

Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Pieterse, M. E., Drossaert, C. H. C., Walburg, J. A., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2017b). Possible mechanisms in a multicomponent email guided positive psychology intervention to improve mental well-being, anxiety and depression: A multiple mediation model. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1388430.

Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., ten Have, M., Lamers, S., de Graaf, R., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2017c). The longitudinal relationship between flourishing mental health and incident mood, anxiety and substance use disorders. European Journal of Public Health, 27(3), 563–568.

Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology. An introduction. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14.

Seligman, M. E., Rashid, T., & Parks, A. C. (2006). Positive psychotherapy. The American Psychologist, 61(8), 774–788. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.61.8.774.

Sergeant, S., & Mongrain, M. (2015). Distressed users report a better response to online positive psychology interventions than nondistressed users. [article]. Canadian Psychologist, 56(3), 322–331. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000034.

Sin, N. L., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: A practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 467–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20593.

Soule, M. C., Beale, E. E., Suarez, L., Beach, S. R., Mastromauro, C. A., Celano, C. M., et al. (2016). Understanding motivations to participate in an observational research study: Why do patients enroll? Social Work in Health Care, 55(3), 231–246.

Spinhoven, P., Ormel, J., Sloekers, P. P., Kempen, G. I., Speckens, A. E., & Hemert, A. M. (1997). A validation study of the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) in different groups of Dutch subjects. Psychological Medicine, 27. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291796004382.

Svartvatten, N., Segerlund, M., Dennhag, I., Andersson, G., & Carlbring, P. (2015). A content analysis of client e-mails in guided internet-based cognitive behavior therapy for depression. Internet Interventions, 2(2), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2015.02.004.

Tausczik, Y. R., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2010). The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 29(1), 24–54.

Thompson, A., Hunt, C., & Issakidis, C. (2004). Why wait? Reasons for delay and prompts to seek help for mental health problems in an Australian clinical sample. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39(10), 810–817.

Vogel, D. L., & Wester, S. R. (2003). To seek help or not to seek help: The risks of self-disclosure. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(3), 351.

Vogel, D. L., Wade, N. G., & Hackler, A. H. (2007a). Perceived public stigma and the willingness to seek counseling: The mediating roles of self-stigma and attitudes toward counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(1), 40.

Vogel, D. L., Wester, S. R., & Larson, L. M. (2007b). Avoidance of counseling: Psychological factors that inhibit seeking help. Journal of Counseling and Development, 85(4), 410–422.

Weiss, L. A., Westerhof, G. J., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2016). Can we increase psychological well-being? The effects of interventions on psychological well-being: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One, 11(6), e0158092. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158092.

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Drossaert, C.H.C. & Bohlmeijer, E.T. People’s Motives to Participate in a Positive Psychology Intervention with Email Support and Who Might Benefit Most?. Int J Appl Posit Psychol 3, 1–22 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-018-00013-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-018-00013-0