Abstract

In this paper, the constitutive framework of hypoplasticity is used to model long-term deformations and stress relaxations of weathered and moisture sensitive rockfill materials. The state of weathering of the material is represented by a so-called solid hardness in the sense of a continuum description. The time-dependent degradation of the solid hardness is a result of progressive weathering caused for instance by hydro-chemical reactions of fluid with the solid material. The degradation of the solid hardness can lead to collapse settlements and creep deformations, which are also called wetting deformations. In contrast to a previous version, a new evolution equation for a more refined modelling of the degradation of the solid hardness is proposed. With respect to a pressure-dependent relative density, the influence of the pre-compaction of the material and also the influence of the pressure level on the stiffness can be modelled in a unified manner using a single set of constants. The performance of the new model is validated by comparison of the numerical simulations with experiments data.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

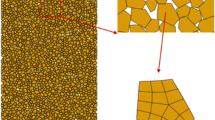

Wetting deformations in the form of collapse and long-term creep settlements are observed in rockfill dams and laboratory experiments. For coarse-grained and weathered rockfills, a change in the moisture content can lead to an acceleration of the propagation of micro-cracks of weathered grains and consequently to grain fragmentation and a reorientation of the grain skeleton into a denser state. The mechanical behaviour of rockfill material can be different for the dry state and the wet state of the material [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. The mechanical properties not only depend on the type of the rock material and its mineralogical composition, but also on the grain size distribution, the compaction, the moisture content, the stress state at contact areas between the grains, and the time-dependent degradation of the solid hardness due to the chemical reaction of the grain material with moisture. Experiments with coarse-grained and weathered rockfills show that wetting deformations cannot be explained based on the concept of effective stresses. This is also obvious for partly saturated coarse-grained materials where the effect of capillary forces between neighbouring particles can be neglected. Thus, the understanding of the physical and thermo-chemical mechanisms of the time-dependent process of weathering is important for an accurate interpretation of the data obtained from monitoring and experiments as well as for numerical modelling.

The focus of this paper is on modelling the properties of weathered rockfill materials using a continuum approach. In particular, a hypoplastic model is used which takes into account the influence of pressure, density, state of weathering and the rate of deformation on the time-dependent, non-linear and inelastic stress–strain behaviour. The state of weathering and the influence of a change in the moisture on the stiffness of the material is related to the solid hardness. To take into account solid hardness as a state variable in the constitutive model, the solid hardness is defined in the sense of a continuum description. In particular, the solid hardness is a measure of the pressure level of the grain assembly under isotropic compression where grain crushing becomes dominant [11, 12]. While in the version by Bauer [13], the time-dependent degradation of the solid hardness is modelled in a simplified manner using only three material parameters, a more sophisticated evolution equation is proposed in this paper. The benefit of the extended evolution equation is a refined distinction of the degradation of the solid hardness related to collapse settlements and to long-term deformations.

2 Constitutive Modelling of Wetting Deformation

In the present constitutive model, the solid hardness is a key parameter to reflect the different stiffnesses of weathered and moisture-sensitive rockfill materials under dry and wet conditions. With respect to a continuum description, the solid hardness is related to the grain assembly under monotonic isotropic compression. More precisely, the solid hardness is a parameter in the following compression law by Bauer [11, 12]:

where \(p\) denotes the mean pressure, i.e. \(p= - {\sigma _{kk}}{\kern 1pt} /{\kern 1pt} 3\), \({e_{{\text{io}}}}\) denotes the void ratio for \(p \approx 0\) and hs is the solid hardness, which is defined for the mean pressure where the compression curve in a semi-logarithmic representation shows the point of inflection as illustrated in Fig. 1a. Parameter n is related to the inclination of the compression curve at the point of inflection.

As the solid hardness is related to a pressure level where grain crushing becomes dominant, isotropic compression experiments have to be carried out up to rather high pressures to calibrate the parameters hs and n. However, in standard laboratories, isotropic compression tests under high pressures are usually more difficult to carry out than high pressure oedometer experiments. In this context, it can be noted that the data of the compression curve obtained from oedometric compression can alternatively be used for the calibration of the solid hardness as outlined in [12].

For weathered rockfills, the solid hardness is usually lower for the wet material than for the dry material as illustrated in Fig. 1b. Wetting of the dry material leads to a degradation of the solid hardness accompanied by collapse settlements, creep and/or stress relaxation. The following evolution equation for the irreversible degradation of the solid hardness was proposed by Bauer [13]:

where \({\dot {h}_{\text{st}}}=\text{d}{h_{\text{st}}}{\text{/d}}t\) denotes the change of the solid hardness with the time t, hst denotes the current value of the solid hardness, hsw is the value of the solid hardness in the asymptotical state for time \(t \to \infty\), and c has the dimension of time and is related to the degradation velocity. With respect to an initial solid hardness of hso, the integration of Eq. (2) leads to:

For rockfill materials with pronounced deformation immediately after changing the moisture content or after full saturation, it could be convenient to distinguish between short-term deformations, also called collapse settlements, and long-term deformations called creep. To distinguish these two effects, the degradation of the solid hardness is decomposed into a part \({\dot {h}_{{\text{st}}1}}\), which is related mainly to collapse settlements, and a part \({h_{{\text{sw}}2}}\), which is related mainly to the long-term deformations. In the modified model, the two parts are combined to obtain a smooth transition between collapse deformations and long-term deformations. The corresponding evolution equations read:

with

and

Herein, the constitutive parameters \({c_{\text{1}}} \leq {c_{\text{2}}}\) and \({h_{{\text{sw1}}}} \geq {h_{{\text{sw2}}}}\) can be obtained by back analysis of creep curves obtained in experiments. For modelling wetting deformations, i.e. long-term deformations, depending on the state of weathering, the solid hardness was implemented into particular models based on the concept of hypoplasticity [14] and generalized plasticity [15]. The performance of the concept of degradation of the solid hardness based on the evolution Eq. (2) has been demonstrated for different rockfill materials by comparing the results obtained from numerical simulations with laboratory experiments, e.g. [16,17,18,19]. For this paper, the extended evolution Eq. (4) was implemented into a simplified hypoplastic constitutive model, which is similar to the one shown by Li et al. [14]. The main constitutive relations can be summarized as follows.

The objective stress rate tensor, \({{{}^{o}}}\sigma\), depends on the current void ration, \(e\), the current state of the solid hardness, \({h_{{\text{st}}}}\), the rate of the solid hardness, \({\dot {h}_{{\text{st}}}}\), the effective Cauchy stress tensor, \(\sigma\), and the rate of deformation tensor, \(\dot {\varepsilon }\). With respect to a Cartesian co-ordinate system, the components of the stress rate read:

Herein, \({\hat {\sigma }_{ij}}={{{\sigma _{ij}}} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\sigma _{ij}}} {{\sigma _{kk}}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\sigma _{kk}}}}\)and \(\hat {\sigma }_{{ij}}^{*}={\sigma _{ij}} - {\delta _{ij}}/3\) denote the normalized Cauchy stress \({\sigma _{ij}}\), and the normalized deviatoric part of \({\sigma _{ij}}\), respectively. Factors \({f_{\text{s}}}\) and \({f_{\text{d}}}\) are functions of the pressure-dependent relative density. The scalar function \(\hat {a}\) is related to the stress limit condition given by Masuoka and Nakai [20] and depends on the critical friction angle \({\varphi _{\text{c}}}\) [21]. With respect to the last term on the right hand side of Eq. (7), creep and stress relaxation can be modelled in a unified manner [13]. \({\delta _{ij}}\)is the Kronecker delta, and parameter \(\kappa\) controls the magnitude and direction of the creep strain [18]. In contrast to the model proposed in [13], simplified representations of factors \({f_{\text{s}}}\) and \({f_{\text{d}}}\) are used in this paper, i.e.

and

in which the term \({h_{\text{i}}}\) is obtained from a consistency condition [13]. The pressure-dependent maximum void ratio \({e_{\text{i}}}\) and critical void ratio \({e_{\text{c}}}\) are modelled as:

and

Herein, \({e_{\text{io}}}\) and \({e_{\text{co}}}\) are the corresponding values for the nearly stress-free state. In contrast to previous versions of the hypoplastic model for weathered rockfill materials, the solid hardness \({h_{{\text{st}}}}\) for isotropic compression is different from the solid hardness \({h_{{\text{sc}}}}\) for the critical void ratio. In particular, \({h_{{\text{sc}}}}<{h_{{\text{st}}}}\), which can be explained by a more pronounced grain damage under deviatoric loading. This is also justified by experimental data for sandstone considered in [14].

With respect to the balance equation of mass, the following relation between the rate of the void ratio and the volume strain rate holds:

For calibration of the constitutive constants, the following strategy can be used. In a first step, the mechanical behaviour of the dry material, i.e. the state of the material before wetting takes place, is considered. For this state the constitutive Eq. (7) reduces to:

Based on Eq. (13) and with respect to the experimental data for the initial dry material, the parameters \({\varphi _{\text{c}}}\), \({n_{}}\), \({h_{{\text{so}}}}\), \({e_{{\text{io}}}}\), \({e_{{\text{co}}}}\), \({h_{{\text{sc}}}}\) and \({\alpha _{}}\)can be calibrated as outlined in more detail for a similar version of the hypoplastic model by Bauer [12] and Gudehus [22]. In the second step, the parameters \({h_{{\text{sw}}}}\), \(c\) and \(\kappa\) in Eq. (2), and for the extended creep model the parameters \({h_{{\text{sw1}}}}\), \({c_1}\), \({h_{{\text{sw2}}}}\) and \({c_2}\)in Eqs. (5) and (6) can be adapted from creep experiments. For the special case of pure creep, i.e. no stress relaxation, the stress rate in Eq. (7) becomes zero and the corresponding constitutive equation reads:

On the other hand, under constant volume the degradation of the solid hardness leads to the following equation for stress relaxation:

For mixed boundary conditions, usually a combination of creep deformation and stress relaxation will take place, which can be computed using the full representation of the constitutive Eq. (7).

3 Verification of the Proposed Model

For verification of the proposed hypoplastic model, the constitutive parameters were calibrated based on data from laboratory tests with broken sandstone [10]. For the dry state of the material, the solid hardness is constant and the values of the corresponding constitutive parameters are summarized in Table 1. More detailed information about the calibration can be found in [14]. It should be noted that the model can capture the influence of the pressure level on the incremental stiffness using only a single set of constants. A comparison of the results of numerical simulations with experimental data obtained from triaxial compression tests is shown in Fig. 2. As can be seen, the proposed hypoplastic model simulates well the essential mechanical properties for different confining stresses with the same set of constants. In particular, the model takes into account the influence of the confining stress on the stiffness at the beginning of deviatoric loading, the peak friction angle, strain softening and the volume strain behaviour.

When wetting of the rockfill material takes place, the incremental stiffness is also influenced by the time-dependent process of degradation of the solid hardness. In the following, the performance of the proposed model (7) is investigated for two different evolution equations for modelling the degradation of the solid hardness. In particular, the evolution Eq. (2) is compared with the extended version (4). The calibration leads to the following two sets of constants:

Constants related to the evolution Eq. (2):

\({h_{{\text{sw}}}}\) = 78.5 MPa; \(c\) = 4.0 h; \(\kappa\) = 0.6.

Constants related to the evolution Eq. (4):

\({h_{{\text{sw1}}}}\) = 90.5 MPa; \({c_{\text{1}}}\) = 0.6 h; \({h_{{\text{sw2}}}}\) = 12.0 MPa; \({c_{\text{2}}}\) = 8.0; \(\kappa\) = 0.6.

In Fig. 3, the numerical results of simulation of creep tests under different isotropic stress states and different deviatoric stress states are compared with the experimental data. In particular, the dashed curves are related to the evolution Eq. (2), the solid curves are related to the extended evolution Eq. (4) and the markers represent the experimental data. A comparison of the creep curves shows that the amount of creep deformation is much higher under higher confining stress states. Furthermore, the creep deformation is also more pronounced under higher vertical stresses. Although the evolution Eq. (2) can capture the dependency of the amount of creep strain for different confining stresses and vertical stresses, the extended evolution equation (4) obviously allows a significant refined modelling. In particular, the deformation during the initial creep period can be better adapted. The latter becomes important for rockfill materials after wetting that exhibit pronounced collapse settlements which occur within a rather short time.

4 Conclusions

This paper proposes a constitutive model for simulation of wetting deformations and stress relaxation in which the solid hardness is a key parameter to reflect the state of weathering of rockfill material. In this model, the solid hardness is defined as a measure of the stress level of the grain assembly under isotropic compression where grain crushing becomes dominant. The time-dependent and irreversible reduction of the solid hardness caused by wetting or other environmental effects is described by an evolution equation depending on the current state of weathering and the degradation velocity. To simulate the evolution of creep deformation and/or stress relaxation, the rate of degradation of the solid hardness is linked to a hypoplastic constitutive equation. In this paper, the performance of two different evolution equations for describing the degradation of the solid hardness is investigated and compared with data from creep experiments. It is shown that the extended evolution equation allows a refined modelling of collapse and long-term settlements in a unified manner.

References

Brauns J, Kast K, Blinde A (1980) Compaction effects on the mechanical and saturation behavior of disintegrated Rockfill. Proc Int Conf Compaction Paris 1:107–112

Ovalle C, Dano C, Hicher PY, Cisternas M (2015) An experimental framework for evaluating the mechanical behaviour of dry and wet crushable granular materials based on the particle breakage ratio. Can Geotech J 52:1–12

Alonso E, Oldecop LA (2000) Fundamentals of rockfill collapse. In: Rahardjo H, Toll DG, Leong EC (eds) Proceedings of the 1st Asian conference on unsaturated soils. Balkema Press, Rotterdam, pp 3–13

Alonso E, Cardoso R (2009) Behaviour of materials for earth and rockfill dams. Perspective from unsaturated soil mechanics. In: Bauer E, Semprich S, Zenz G (eds) Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on long term behaviour of dams. Graz University of Technology, Graz, pp 1–38

Fang XS (2005) Test study and numerical simulation on wetting deformation of gravel sand. Master thesis, Hohai University, Nanjing (in Chinese)

Oldecop LA, Alonso E (2004) Testing rockfill under relative humidity control. Geotech Test J 27(3):1–10

Li GX (1988) Triaxial wetting experiments on rockfill materials used in Xiaolangdi earth dam. Research report 17-1-2-88031. Tsinghua University, Beijing

Oldecop LA, Alonso EE (2007) Theoretical investigation of the time-dependent behavior of rockfill. Geotechnique 57(3):289–301

Fang XS (2005) Test study and numerical simulation on wetting deformation of gravel sand. Dissertation for the Master Degree, Hohai University, Nanjing (in Chinese)

Fu H, Ling H (2009) Experimental research on the engineering properties of the fill materials used in the Cihaxia concrete faced rockfill dam. Research report. Nanjing Hydraulic Research Institute, Nanjing (in Chinese)

Bauer E (1995) Constitutive modelling of critical states in hypoplasticity. In: Pande GN, Pietruszczak S (eds) Proceedings of the 5th international symposium on numerical models in geomechanics. Balkema Press, Rotterdam, pp 15–20

Bauer E (1996) Calibration of a comprehensive hypoplastic model for granular materials. Soils Found 36(1):13–26

Bauer E (2009) Hypoplastic modelling of moisture-sensitive weathered rockfill materials. Acta Geotech 4:261–272

Li L, Wang Z, Liu S, Bauer E (2016) Calibration and performance of two different constitutive models for rockfill materials. Water Sci Eng 9(3):227–239 (pp. 1–12)

Wang ZJ, Chen SS, Fu ZZ (2015) Dilatancy behaviors and a generalized plasticity model of rockfill materials. Rock Soil Mech 36(7):1931–1938 (in Chinese)

Fu Z, Bauer E (2009) Hypoplastic constitutive modeling of the long term behaviour and wetting deformation of weathered granular materials. In: Bauer E, Semprich S, Zenz G (eds) Proceedings of the 2nd international conference on long-term behaviour of dams. Graz University of Technology, Graz, pp 437–478

Bauer E, Fu ZZ, Liu SH (2010) Hypoplastic constitutive modelling of wetting deformation of weathered rockfill materials. Front Archit Civ Eng China 4(1):78–91

Bauer E, Fu ZZ, Liu SH (2012) Influence of pressure and density on the rheological properties of rockfills. Front Struct Civ Eng 6(1):25–34

Bauer E, Fu Z, Liu S (2011) Constitutive modelling of rheological properties of materials for rockfill dams. In: Pina E, Portela J, Gomes J (eds) Proceedings of the 6th international conference on dam engineering, Lisbon, Portugal (CD ROM). CI-Premier Pte Ltd, Singapore, pp 1–14

Matsuoka H, Nakai T (1997) Stress–strain relationship of soil based on ‘SMP’. In: Proceedings of Specialty Session 9, IX international conference on soil mechanics and foundation engineering, Tokyo, pp 153–162

Bauer E (2000) Conditions for embedding Casagrande’s critical states into hypoplasticity. Mech Cohes Frict Mater 5:125–148

Gudehus G (1996) A comprehensive constitutive equation for granular materials. Soils Found 36(1):1–12

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by Graz University of Technology. The author wishes to thank Dr. Z. Z. Fu from the Nanjing Hydraulic Research Institute for providing experimental data. Mr. L. Li and Mr. M. Khosravi supported this paper with some drawings and numerical calculations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bauer, E. Constitutive Modelling of Wetting Deformation of Rockfill Materials. Int J Civ Eng 17, 481–486 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40999-018-0327-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40999-018-0327-7