Abstract

Steel-to-glass laminated connections, which have recently been developed, limit stress intensifications on the glass and combine strength and transparency. Transparent Structural Silicone Adhesive (TSSA) connections have been used in several projects worldwide; however, the hyperelastic and viscoelastic nature of the material has to date not been fully investigated. In this work, the first objective is to investigate the mechanical response of TSSA connections under static and cyclic loading by means of experimental tests. Firstly, the shear behaviour of TSSA circular connections is characterized by means of monotonic and cyclic loading tests. The adhesive exhibits significant stress-softening under repeated cycles that becomes more severe as the maximum load increases. Secondly, TSSA circular connections are subjected to monotonic and cyclic tensile loading of increasing maximum load. The way whitening propagates on the adhesive surface shows some consistency comparing the cases of static and cyclic loading. The second objective is to analytically describe the deformation behaviour of the adhesive based on hyperelastic prediction models. Uniaxial and biaxial tension tests are combined with the simple shear tests, for the material characterization of TSSA. The hyperelastic material parameters are calibrated by a simultaneous multi-experiment-data-fit based on the nonlinear least squares optimization method. The softening behaviour observed in shear tests is modeled based on a simplified pseudo-elastic damage model proposed by Ogden–Roxburgh. A first attempt is also made to model the actual softening response of the adhesive. A less conservative approach proposed by Guo, also based on the theory of pseudo-elasticity, proved to give a good approximation of the actual cyclic response of the adhesive.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

1.1 Transparent Structural Silicone Adhesive

Transparent Structural Silicone Adhesive is a crystal clear silicone adhesive film produced by Dow Corning that exhibits thermal stability and excellent weatherability (Sitte et al. 2011). It was developed for frameless glazed facade applications with steel to glass laminated adhesive connections. It is an elastomeric one-component addition cured silicone with no by-products (and no odor), characterized by nanosilica and cross-linked polymers (Santarsiero et al. 2016a). TSSA laminated connections have been used in several projects, such as the Dow Corning’s new European Distribution Centre in Belgium. In this project, TSSA frameless spider connections allowed the use of insulated glazed units, easier fabrication on site and avoided drilling the glass.

Overend et al. (2013) tested TSSA single lap joints and T-peel specimens. The results showed that TSSA exhibits sufficient strength in combination with a flexible behavior, which is unique among other transparent heat-curing foils, such as SentryGlas. In the work of Sitte et al. (2011), the tensile and shear monotonic behavior of TSSA connections was investigated at room temperature. In addition, the behaviour of TSSA bulk material was also investigated at a constant displacement rate. The results showed that TSSA exhibits a hyperelastic response. Cyclic loading tests were also performed, and results showed the appearance of the stress softening phenomenon, also referred to as Mullins effect.

In the work performed by Santarsiero et al. (2016b), TSSA dumbbell shaped specimens were subjected to uniaxial tensile tests. The tests were performed at different temperatures (\(-\,20, 23\) and \(80\,{^{\circ }}\hbox {C}\)) and displacement rates (1, 10 or 100 mm/min). A nonlinear stress–strain response was also observed, confirming the hyperelastic nature of TSSA. Temperature variations did not significantly influence the stiffness of the adhesive; however, the stress and strain at the point of failure showed a temperature dependency. Santarsiero et al. (2016a) also performed shear and tensile tests on TSSA laminated circular connections. The specimens consisted of annealed glass plates with a laminated stainless steel circular button with diameter 50 mm. The shear behaviour of those connections proved to be mainly linear until failure, a fact which was also observed in the work of Hagl et al. (2012) and Sitte et al. (2011). On the other hand, the mechanical response of laminated circular connections under tensile load appeared to be bilinear, showing a very stiff response followed by a hardening phase. The influence of temperature on the shear and tensile behaviour of the connection proved to be negligible.

Tensile tests of TSSA dumbbells and TSSA metal to glass connections (Santarsiero et al. 2016b; Sitte et al. 2011) have showed that the adhesive does not remain transparent throughout testing. Its colour changes from completely transparent to white above a certain stress level. According to the manufacturing company, Dow Corning\({\textregistered }\), the whitening phenomenon is expected when the local stress exceeds 2 MPa. In the work of Santarsiero et al. (2016a) and Sitte et al. (2011), the whitening of TSSA is clearly visible at engineering stresses close to 5 MPa.

1.2 The Mullins effect

Elastomer or rubber-like materials, such as TSSA, undergo a stress softening phenomenon under cyclic loading. More specifically, they exhibit a hysteretic behaviour, which is characterized by a difference between the loading and unloading mechanical response. This softening effect, also referred to as the Mullins effect, was first extensively studied by Mullins (1969) in the 1970’s. More specifically, the Mullins effect describes the dependency of the stress–strain curve of rubbers on the maximum load previously encountered. When the load is less than the previous maximum load, the loading response of rubbers follows the path of the undamaged ‘virgin’ material, whereas the unloading response is characterized by a softening behaviour. Whenever the load increases above its prior maximum value, the stress–strain curve changes, resulting in more severe softening behaviour.

Several physical interpretations have been proposed to understand the stress-softening phenomenon of rubbers. However, there is still no universal consensus on the origin of this phenomenon (Diani et al. 2009). Blanchard and Parkinson (1952) expressed the theory that the stress-softening effect is the result of bond ruptures taking place during stretching. According to their theory, the weaker bonds (or physical bonds) are ruptured first, followed by the stronger (or chemical) bonds. Houwink (1956) used instead the theory of molecules slipping over the surface of fillers, as a fact which causes new bonds to be created. These new bonds are of the same physical nature, but they are located at different places along the rubber molecules (Diani et al. 2009). According to this theory, the phenomenon could be reversible with exposing the rubber to elevated temperatures. Other theories have been developed by Kraus et al. (1966) who attribute the stress-softening effect to the rupture of carbon-black structure, which is used as reinforcing filler in many rubber products.

1.3 Objectives

The monotonic response of TSSA dumbbell specimens and TSSA laminated circular connections has been already investigated by Hagl et al. (2012), Santarsiero et al. (2016b) and Sitte et al. (2011). However, very few experimental data exist on the cyclic behaviour of TSSA, and the appearance of the Mullins effect.

In this study, TSSA laminated circular connections with diameter 50 mm are subjected to a series of monotonic and cyclic-shear and tensile tests. The first objective is to study the mechanical response of these connections under loading cycles and to observe if they exhibit the stress-softening phenomenon. Secondly, the development of the whitening phenomenon will be compared under monotonic and cyclic loading. Thirdly, the propagation of whitening both for the cases of static and cyclic loading and the recovery of the phenomenon when removing the load is studied.

Even though significant research has been performed on the mechanical response and the stress state of circular TSSA connections, as well as a generalized failure criterion has been developed by Santarsiero et al. (2018), limited information can be found in literature on the non-linear TSSA constitutive law. This makes it difficult to produce a finite element model that sufficiently describes the behaviour of TSSA laminated connections under certain specific stress states. The behaviour of elastomeric materials, such as TSSA, can be described by a broad range of hyperelastic non-linear constitutive laws, most of which can be implemented in finite element software to describe the behaviour of elastomers. The accuracy of the predicted mechanical response largely depends on the chosen model. Therefore, the final objective of this study is the calibration of several material models based on experimental data and the assessment of the suitability of each model to describe the stress–strain response of the adhesive.

2 Method

2.1 Materials and specimens

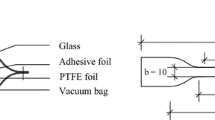

The tested specimens (see Fig. 1) consist of a solid 316L stainless steel connector with diameter 50 mm, height 20 mm and tolerance h9 [ISO 286] (Santarsiero et al. 2016a). The connector is located in the center of a \(150\,\times \,150\) mm annealed glass plate of 15 mm thickness. The TSSA foil is 1 mm thick. The connector has a circular shape, which is favorable as in this way stress concentrations at the edges are avoided, unlike the case of rectangular connectors (Santarsiero et al. 2016b). The bonded surface was machined (uni-directional polishing) with roughness of 8 micron, to ensure good contact of the materials (Santarsiero et al. 2016a). Prior to lamination, the substrates were cleaned with isopropanol and primed with a heptane based solvent specially developed for Dow Corning\(^{\textregistered }\) TSSA (Dow Corning\(^{\textregistered }\) 92-023 Primer).

2.2 Shear test set-up

Tests are performed with a SCHENCK testing machine and a 10 KN load cell at the Stevin Laboratory at the Faculty of Civil Engineering and Geosciences at TU Delft. A specially designed steel set-up (see Fig. 2) is made to ensure that the test approximates, as much as possible a simple shear stress state. The shear load is transferred via a 10 mm thick steel plate with a circular hole (diameter 50.1 mm) in the middle. The circular hole renders possible to impose inverse shear loading to the connection. The steel plate is connected to a steel rod which in turn is connected to the load cell and fixed to the upper part of the machine. The rest of the steel set-up ensures that the glass specimen is rigidly fixed to the machine base. The base can move upwards and downwards and introduces in this way the shear load into the system. The steel plate that transfers the shear load to the connection is aligned to the interface between the glass plate and the adhesive. Its thickness is reduced to 3 mm close to the circular hole (see Fig. 3). In this way, the eccentricity of the shear load is minimized (Santarsiero et al. 2016b), in order to approach, as much as possible a simple shear stress state. Aluminium plates with 2 mm thickness are placed on the interfaces of glass and steel to reduce the probability of glass breakage during the test.

The relative displacement between the glass and the connector is measured by two Linear Variable Differential Transformers (LVDTs) with a stroke of \(\pm \,5\,\hbox { mm}\) which are placed on the right and left side of the connector. The LVDTs stand on two small aluminium L-profiles, which are bonded on the glass surface. In this way, it is possible to measure the relative displacement of glass and steel and thus the displacement of the adhesive. The behaviour of TSSA in shear is recorded on video during the tests, as the set-up allows visual inspection of the adhesive through the glass pate.

A series of static and cyclic tests are performed at average room temperature of \(27\,\pm \,0.04\,{^{\circ }}\hbox {C}\). The monotonic tests are performed in displacement control at a displacement rate of 1 mm/min. The cyclic tests are conducted in force control and loading cycles are performed from 0 to +P or from −P to +P (where P refers to the maximum load level of the cycle) at 0.1 or 1 Hz. The loading pattern is based on the guideline ETAG 002 (EOTA Recommendation 2001), which specifies a trapezoidal-shaped function with time for mechanical fatigue tests of structural sealants. The guideline describes a linear increase of load with time, followed by a stable phase where the maximum (or minimum load) remains constant to counteract creep effects. When unloaded, a steady state of zero (or nearly zero) loading follows. In this way, the mechanical response of the adhesive is isolated, as much as possible, from viscoelastic effects related to creep or relaxation, in order to derive the time-independent response of TSSA. Cycles are performed at different load levels that begin from a loading loop of 0 to 1 or \(-1\) to 1 kN, which is repeated 50 times. Subsequently the maximum (and minimum) load increases in absolute terms with a step of 1 kN every 50 cycles. Loading cycles are performed up to 8 kN. Performing cycles up to this load level would avoid failure of the specimen during cyclic loading, since previously recorded failure loads range between 9.3 and 11.9 kN (Santarsiero et al. 2016a). Data are acquired with a frequency of 10 Hz.

Figure 4 illustrates the load versus time relation. The left graph describes the tests that involve reverse shearing, whereas the right graph describes shearing in only one direction. The duration of the steady state of the load is indicated either with t1, when the load is maximum, or t2, when the load is nearly zero. The values of t1 and t2 (t1 \(=\) t2) are 2 or 0.2 s corresponding to frequencies 0.1 and 1 Hz.

2.3 Tensile test set-up

Tests were performed with a SCHENCK testing machine and a 10 kN load cell. A steel set-up is made to restrain the glass plate during loading. More specifically, a 35 mm thick steel plate with a circular hole (diameter 80 mm) in the middle is bolted onto two UPE 100 sections (European Standard U Channels with Parallel Flanges), which in turn are fixed onto the machine base (see Fig. 5). The glass specimen is positioned right underneath the thick steel plate. The UPE sections allow the placement of a camera right below the glass specimen. For safety reasons, two pieces of timber uphold the glass plate. Between the steel and glass plates an aluminium ring is placed to ensure that the force is equally distributed (see Fig. 6). The ring has an external diameter of 120 mm and has a width of 20 mm. A cardboard mould was used to make sure that the aluminium ring is always positioned in the center of the specimen. The stainless steel button is connected to a hinge with a M10 steel rod. The hinge is used to make sure that the force is well centered relative to the specimen. The tensile force is introduced to the system by displacing the machine base (Fig. 7). The displacements are measured by means of three LVDTs with a stroke of \(\pm \,1\hbox { mm}\), uniformly distributed around the stainless steel button. This is to consider possible rotations induced by fabrication tolerances or imperfections (Santarsiero et al. 2016b). The LVDTs are mounted onto an aluminium ring, which in turn is rigidly fixed onto the stainless steel button.

A series of static and cyclic tests are performed at average room temperature of \(23.7\,\pm \,2.3\,{^{\circ }}\hbox {C}\). It must be noted that room temperature differences are not expected to influence the results, since TSSA exhibits stability against temperature variations (Santarsiero et al. 2016a). The static tests are performed in displacement control at a displacement rate of 1 mm/min. The cyclic tests are conducted in force control and the specimens are subjected to loading cycles under two different frequencies of 0.1 and 1 Hz. The loading pattern follows again the trapezoidal form described in the guideline ETAG 002. Loading cycles are performed at different load levels. The cycles begin from a loading loop of 0 to 1 kN that is repeated 50 times. Subsequently, the maximum load increases with a step of 1 kN every 50 cycles. The specimens are loaded up to a maximum load of 8 kN. Data are acquired with a frequency of 10 Hz.

2.4 Tests summary

The summary of the tests performed is given in Table 1.

3 Experimental results

3.1 Shear test results

The monotonic response of TSSA connections under shear load is shown in Fig. 8. This is in agreement with the results of Hagl et al. (2012), Santarsiero et al. (2016b) and Sitte et al. (2011). From the video recording, very slight whitening is visible starting approximately at a load of 7 kN. The deformation behaviour of TSSA in shear exhibits considerable difference under static and cyclic loading. Figure 9 plots the first (\(1{\mathrm{st}})\) and the last (\(50{\mathrm{th}})\) cycles for each load level for tests where repeated loading cycles were performed from 0 to +P at 0.1 Hz. The stress-softening phenomenon is observed even at loading cycles performed at low load levels and it becomes more critical as the maximum load increases. A relation is observed between the magnitude of softening and the permanent deformations at the stress-free state, as for higher damage due to softening, larger permanent deformations are observed. Isolating the cycles for each load level, the damage appears to increase with the number of cycles. In addition, throughout the test, very slight whitening of the adhesive surface takes place, which is barely visible.

Figures 10 and 11 compare the deformation behaviour of the adhesive when loaded cyclically from −P to \(+\)P under two different frequencies. Figure 10 illustrates the mechanical response of specimens loaded at a frequency of 0.1 Hz. The softening response resembles the one of Fig. 9. Most of the tested specimens failed to reach loading cycles up to 8 kN, unlike the case of shearing in only one direction. Specimens imposed to a higher frequency of 1 Hz, also exhibit a stress softening behaviour during unloading. However, in this case, the stiffness appears to increase during the loading phase (see Fig. 11).

Figure 12 compares the mechanical response of the adhesive when a shear load is applied in both directions. “Positive” and “negative” shear refer to the direction of the load. The loads and displacements, corresponding to negative shear, are converted to their absolute values and compared with the results taken from positive shear. When the adhesive undergoes negative shear, a small decrease of the absolute deformations is observed. This is in the range of 6% and presumably it is due to the fact that negative shear also recovers the permanent deformations caused by the previous positive shearing.

3.2 Tensile test results

Figure 13 illustrates the stress–strain graph obtained by the tensile static tests. The graph is divided into two phases and resembles the experimental results obtained at \(23\,{^{\circ }}\hbox {C}\) in the research performed by Hagl et al. (2012) and Santarsiero et al. (2017). The mechanical response starts from a linear behaviour up to approximately 8 kN. Then, the second phase starts where the stiffness is significantly reduced and the behaviour of the adhesive exhibits an approximately linear behaviour until failure.

As expected, the whitening phenomenon of TSSA is observed during the tensile test. The whitening starts to be visible in small dots at approximately 80% of the connection radius (see Fig. 14), a fact which is completely in line with the observations of Santarsiero et al. (2017). Subsequently, it forms a crescent shape that propagates towards the middle of the connection and finally covers the entire surface. The only part that remains transparent is a very thin outer ring of the connecting surface. In the work of Santarsiero et al. (2017), the propagation of whitening on a circular connection subjected to tensile loading is extensively investigated and for the sake of brevity not repeated here.

Figure 15 illustrates the response of the adhesive recorded during the first and last cycle for each maximum load level at a frequency of 0.1 Hz. The results show that for loading cycles up to 6 kN, the loading and unloading curves overlap, meaning that response of the material is (almost) perfectly linear. When the maximum load increases to 7 kN, a very small deviation between the curves representing the \(1{\mathrm{st}}\) (continuous line) and the \(50{\mathrm{th}}\) cycle (dotted line) is observed, a fact which indicates the beginning of the stress-softening effect. More severe softening is observed during the loading cycles up to 8 kN. The softening behaviour of the material appears to increase dramatically as the maximum load increases from 7 to 8 kN and continuous to increase with the number of cycles. Nevertheless, TSSA does not exhibit any permanent deformations under cyclic loading.

Figure 16 illustrates the development of the whitening phenomenon under loading cycles. For loading cycles up to 6 kN, whitening appears in a crescent shape at 80% of the radius. As the cycles increase, whitening appears in the same position and shows a small spread around this point. When the maximum stress exceeds 6 kN, the whitening effect seems to spread faster and in the end covers the entire surface, leaving a small ring at the perimeter still transparent. It must be noted that in all of the cycles performed, the whitening completely disappeared when the load was removed, leaving no trace of whitened surface. The propagation of whitening and the stress level it appears proved to be consistent for most of the specimens. Inconsistencies are observed in defected specimens that failed earlier than expected and showed more sever softening behaviour. In the work of Sitte et al. (2011), this is considered as a positive feature, as the propagation of whitening may provide an indication of the quality of bonding without destroying the connection.

4 Analytical modeling

When numerically analyzing adhesive point-fixings using a finite element software, the accuracy of the results largely depends on the predefined material model. The glass and steel elements can be simulated with linear elastic properties; however, adhesives, such as TSSA, require specific mathematical expressions to describe their behaviour. The suitability of the model is assessed by curve fitting various mathematical expressions to experimental data that is generated in the current paper and experimental data derived from literature.

4.1 Theoretical background

Nonlinear elasticity problems are often solved using strain energy functions (Marckmann and Verron 2006). The constitutive models are expressed as a function of the deformation gradient tensor. Most hyperelastic material models are based on the assumption that elastomers are perfectly incompressible. Even though rubber-like materials have a Poisson’s ratio very close to 0.5, it is not correct to assume that their behaviour is incompressible. Rubbers still exhibit volume changes, especially when they are under a confined state. For this reason, the mathematical modeling of the mechanical behaviour of elastomers requires the strain energy function to be broken down to an isochoric and a volumetric part. The decoupled strain energy function is written as

where W, the strain energy density (or potential) or the strain per unit of reference volume; F, the deformation gradient tensor; \(W_{iso} (\overline{F} )\), the isochoric part of the strain energy function, corresponding to the case of perfect incompressibility; \(W_{vol} (J)\), the volumetric part of the strain energy function, accounting for volume changes.

The majority of hyperelastic material models that assume incompressible behaviour are based on the volume-preserving deformation tensor \(\bar{\hbox {F}}\). A model that is solely based on this assumption can only be considered acceptable for non-confined cases, such as uniaxial tension or compression, simple shear and biaxial stress states. Most finite element codes express the strain energy function in terms of the principal invariants of the left Cauchy–Green tensor \(\bar{\hbox {B}}\) or in terms of the principal extension ratios \(\lambda _{1}\),\(\lambda _{2}\),\(\lambda _{3}\), as

where

4.2 Method

The curve fitting process requires the reformulation of the strain energy functions in terms of engineering stresses and strains. In large strain problems, based on the finite deformation theory, the stress state of rubbers can be expressed either in terms of the Cauchy (or true) stress tensor \({\varvec{\upsigma }}\) or of the \(1{\mathrm{st}}\) Piola–Kirchhoff tensor P. The relation between the stress tensors is

where J, the Jacobian of the deformation gradient tensor (J \(=\) det(F)); \(\upsigma \), the Cauchy stresses tensor.

The Cauchy stress tensor defines the stress state of the body in the deformed state, whereas the \(1{\mathrm{st}}\) Piola–Kirchhoff tensor defines the stress state relative to the reference configuration. The \(1{\mathrm{st}}\) Piola–Kirchhoff stresses are also referred to as engineering stresses. In literature (Drass et al. 2017a; Guo and Sluys 2006; Ogden et al. 2004), one can find the stress state of rubbers expressed also in Biot (or nominal) stresses \(\hbox {t}_{\mathrm{i}}\). For common deformation states, such as uniaxial or biaxial tension and compression or simple shear, the Biot stresses are equal to the \(1{\mathrm{st}}\) Piola–Kirchhoff stresses, since no rotation of the rigid body takes place under these stress states.

where T, the Biot (or nominal) stress tensor; \(\hbox {R}^{\mathrm{T}}\), the transpose of the rotation matrix (the rotation matrix R is equal to the identity matrix I for commonly tested deformation states).

It is common to assess the behaviour of elastomeric materials based on their undeformed state since experimental data are expressed in terms of engineering stresses and strains. For this reason, the derivation of the \(1{\mathrm{st}}\) Piola–Kirchhoff stress is considered more suitable for the curve fitting process. However, this tensor does not provide any physical interpretation and thus the Cauchy stress tensor provides better insight when numerically analyzing rubber materials. The relation of the principal Cauchy stresses \(\upsigma _{\mathrm{i}}\) with the strain energy density is

The relation of the Cauchy stress tensor with the corresponding Biot (or engineering) stresses (Drass et al. 2017b; Guo and Sluys 2006; Marckmann and Verron 2006; Mooney 1940; Ogden et al. 2004), which are measured directly in experiments, is

In this study, the results of the shear tests are combined with data from uniaxial tension and biaxial tests conducted by Drass et al. (2017a) and Santarsiero et al. (2016a), respectively. Drass et al. performed biaxial bulge tests, where water pressure was applied to the TSSA foil. In this way, a biaxial deformation state was induced in the adhesive, based on the principle of an inflating balloon. Santarsiero et al. performed uniaxial tension tests on dumbbell specimens at a displacement rate of 1 mm/min. The size of the dumbbell specimens was based on EN ISO 37-type 2 (International Organization for Standardization 2011), with only the transversal dimensions increased with a factor of 2.5. Both tests were performed at room temperature.

This work aims to calibrate only the material parameters for the isochoric part of TSSA, which are suitable for non-confined deformation states. For this purpose, material models with maximum three parameters are going to be considered, since larger number of parameters also requires a larger experimental database to be fitted. The deformation gradient tensor and the stress reformulations for each deformation state (uniaxial, shear and biaxial) are summarized in Table 2. For future research, it is recommended that oedometric tests are performed, in order to calibrate the bulk modulus of TSSA (see “Appendix A”).

The calibration of the material parameters is based on the non-linear least square optimization method. The stress–strain curves derived from the shear tests are averaged by means of a Matlab\(^{\textregistered }\) script that interpolates between the ordinate values of each dataset and subsequently averages the corresponding abscissa values. A Matlab\(^{\textregistered }\) script is also developed for the curve fitting process. The accuracy of the material model is increased when datasets from multiple deformation states are taken into account, because in this case a single set of material parameters is used to describe all deformations states. The fitting process is based on the least squares method that calibrates the material constants by minimizing the value of the error function E. The Matlab\(^{\textregistered }\) functions Lsqcurvefit and Lsqnonlin were used for this purpose. Matlab\(^{\textregistered }\) also offers the option to minimize the error either using the ’Trust-region-reflective’ or the ‘Levenberg–Marquardt’ algorithm. For both cases the results were the same. The error function is

where, \(\hbox {n}_{\mathrm{UT}}\), \(\hbox {n}_{\mathrm{S}}\), \(\hbox {n}_{\mathrm{ET}}\)—the number of data points of uniaxial tension, shear and equibiaxial tension tests, respectively.

The fitting of each model to the experimental data is assessed by introducing the coefficient of determination \(\hbox {R}^{2}\), which takes the value of 1 in case of perfect fitting.

where \(y_i ,\hat{{y}}_i \) and \(\overline{y_i } \), the test data—the model data and the average value of the test data, respectively.

4.3 Modeling the stress-softening phenomenon

Several continuum mechanics and pseudo-elastic models exist that describe the stress-softening phenomenon observed in elastomers. In practice, few of them are used and are commercially available in finite element analysis software. Such modes were proposed by Simo (1987), Govindjee and Simo (1991), Ogden and Roxburgh (1999), Chagnon et al. (2004), Qi and Boyce (2004) and many others. It must be noted that these models can describe only a small fraction of the structural properties of elastomers, since the mechanical response of these materials changes constantly with the number of cycles. The models based on continuum mechanics theory are considered complex and computationally demanding. On the other hand, most finite element software make use of pseudo-elastic material models (see “Appendix B”) that make use of a damage parameter to describe the loading path with a common strain energy function and the unloading and reloading paths with a different strain energy function that is based on the undamaged situation.

5 Discussion

Figure 17 shows the performance of several hyperelastic models (see “Appendix A”) for describing the uniaxial, shear and biaxial stress state of the adhesive. It is evident that the Yeoh model fails to reproduce all three deformation states, as well as that the three-parameter Mooney–Rivlin model fails to approach the biaxial stress–strain behaviour of TSSA. This can be explained by the fact that higher order material models, such as the Yeoh and the three-parameter Mooney–Rivlin model, are intended for large deformations and often show poor performance at small strains. TSSA exhibits maximum strains of the order of 140–200%, whereas high order models, such as the Yeoh model, are intended for fitting over a large strain range, such as 400–700%. The rest of the models show a very good performance in shear, but they become weaker in uniaxial and even more in biaxial tension. The Gent–Thomas model appears to reproduce better the uniaxial tension data, whereas for the case of biaxial tension it is difficult to clearly distinguish which model performs best. The performance of the Gent–Thomas and the two parameter Mooney–Rivlin model though appears to be very similar and gives good results for stretches up to 180%. The calibrated material parameters and the corresponding coefficients of determination are given in Table 3.

The next step is to calibrate the damage models for the simulation of the stress-softening phenomenon. Cyclic shear tests showed that the deformation behaviour of the adhesive changes according to the maximum load applied and the number of cycles. This means that there is a need to calibrate different damage parameters for every maximum load tested. Furthermore, energy dissipation analysis was conducted, to understand if the constant shift the stress–strain response to the right tends to stabilize after a certain number of cycles.

In Fig. 18, the calculated dissipated energy in MPa (or \(10^{-6}\,\hbox {J/m}^{3})\) is plotted against the number of cycles. It is typical in rubbers exhibiting the stress softening phenomenon, that during the first cycle a large amount of energy is dissipated. This is in fact observed in the work of Sitte et al. (2011), where TSSA was subjected to uniaxial, shear and equibiaxial cyclic tests. After the first cycles the dissipated energy of rubbers either gradually decreases, in case of displacement controlled tests, due to relaxation, or increases, in case of force controlled tests, due to creep. The latter is in fact observed in the shear test results performed for purpose of this study, since the tests are carried out in force control.

For maximum engineering stresses up to 2 kN, the material does not show significant creep effects and this is the reason the dissipated energy remains almost stable after the first cycle. For loading cycles performed above 2 kN the effect of creep becomes clearly visible, as the dissipated energy does not remain stable after the first cycle but shows an increase. In most cases the rate of increase seems to decrease as we approach the \(50{\mathrm{th}}\) cycle, meaning that the dissipated energy tends to stabilize with the number of cycles. For cycles performed up to 3 kN, the dissipated energy has almost stabilized until the \(50{\mathrm{th}}\) cycle, a fact which indicates that the unloading and reloading response will not further keep shifting to the right. For cycles above 3 kN, the dissipated energy tends to stabilize approaching \(50{\mathrm{th}}\) cycle; however, it is clearly not stabilized yet. In this case, more cycles are required to detect the point where the dissipated energy and thus the mechanical response of TSSA stabilize. It must be noted that for the calibration of the damage factor for the simulation of the stress-softening phenomenon, the dataset of the stabilized response should be considered. This is because, creep effects may prove to be decisive for the deformation state of the adhesive, and thus it is important that the model reproduces the behaviour of the adhesive at its stabilized state.

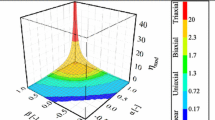

Figure 19 shows the fitting of the Ogden–Roxburgh model to the experimental data, which appears to describe the response of TSSA fairly accurate. This model though does not consider permanent deformations at the stress-free state and this is the reason it becomes weaker in describing the deformations of the adhesive at low stress levels. The Ogden–Roxburgh model does not account for different unloading and reloading branches and thus for cases such as the one observed for TSSA, the problem should be further simplified. On the other hand, Guo and Sluys (2006) proposed a model that considers this differennce in loading and reloading mechanical response. Figure 20 shows the performance of the Guo model in describing the actual response of TSSA under cyclic shear loading, accounting for the divergence in the unloading and reloading paths. Here, the fitting of cycles up to maximum loads of 1, 3, 4 and 5 kN is indicatively given. The model reproduces well the behaviour of the adhesive at moderate stress levels, while showing some weakness at cycles performed at very low or very high stresses. The calibrated coefficients based on the Ogden–Roxburgh and Guo models are given in Tables 4 and 5, respectively.

6 Conclusion

This research focused on investigating the static and cyclic mechanical response of TSSA laminated circular connections under shear and tensile loading. The shear cyclic response showed significant stress softening that depends on the maximum load previously encountered and the applied frequency. This softening behaviour deviates from the static response, which appears to be mainly linear, and thus a nonlinear constitutive law is needed to simulate the cyclic response of TSSA. The mechanical response of the connections subjected to reverse shearing appears to be the same in both directions, meaning that there is no need to account for any divergence of the response between “positive” and “negative” shear, when it comes to the simulation of the deformation behaviour. Tensile cyclic loading tests showed that the stress-softening phenomenon starts to develop at very high stress levels above the working limit of the connection. Furthermore, the propagation of the whitening phenomenon appeared to be similar under static and cyclic loading. Whitening completely disappears when the load is removed, a fact which must be carefully considered in case the phenomenon is utilized as a warning for overloading. In civil engineering practice, stress peaks usually appear instantaneously, a fact which means that whitening is expected to occur instantly. Nevertheless, the propagation of the whitening effect shows some consistency, a fact which is considered advantageous as it may be used as an indicator of the quality of bonding in non-destructive quality assurance testing. Finally, the shear tests were combined with uniaxial and biaxial test data to calibrate various hyperelastic models for the simulation of the mechanical response of TSSA. The softening behaviour observed in shear tests was modeled based on the simplified approach proposed by Ogden and Roxburgh. A less conservative approach was suggested based on the model of Guo, which provides a good approximation of the actual cyclic response of the adhesive. This model may be implemented in FE analysis through a user-defined subroutine and be used to predict the changes in stiffness observed during the tests.

References

Ali, A., Hosseini, M., Sahari, B.B.: A review of constitutive models for rubber-like materials. Am. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 3(1), 232–239 (2010)

Besdo, D., Ihlemann, J.: A phenomenological constitutive model for rubberlike materials and its numerical applications. Int. J. Plast. 19, 1019–1036 (2003)

Blanchard, A.F., Parkinson, D.: Breakage of carbon-rubber networks by applied stress. Ind. Eng. Chem. 44, 799–812 (1952)

Chagnon, G., Marckmann, G., Verron, E.: A comparison of the Hart–Smith model with Arruda–Boyce and gent formulations for rubber elasticity. Rubber Chem. Technol. 77(4), 724–735 (2004)

Diani, J., Fayolle, B., Gilormini, P.: A review on the Mullins effect. Eur. Polym. J. 45(3), 601–612 (2009)

Dias, V., Odenbreit, C.: Investigation of hybrid steel-glass beams with adhesive silicone shear connection. Steel Constr. 9(3), 207–221 (2016)

Dispersyn, J., Hertele, S., De Waele, W., Belis, J.: Assessment of hyperelastic material models for the application of adhesive point-fixings between glass and metal. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 77, 102–117 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijadhadh.2017.03.017

Drass, M., Schwind, G., Schneider, J., Kolling, S.: Adhesive connections in glass structures—part I: experiments and analytics on thin structural silicone. Glass Struct. Eng. 3, 39–54 (2017a). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40940-017-0046-5

Drass, M., Schwind, G., Schneider, J., Kolling, S.: Adhesive connections in glass structures-part II: material parameter identification on thin structural silicone. Glass Struct. Eng. 3, 55–74 (2017b). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40940-017-0048-3

European Organisation for Technical Approvals: ETAG 002 - Guideline for European Technical approval for Structural Sealant Glazing Systems (SSGS) Part 1: Supported and Unsupported System (2001)

Gent, A.N., Thomas, A.G.: Forms for the stored (strain) energy function for vulcanized rubber. J. Polym. Sci. 28(118), 625–628 (1958)

Govindjee, S., Simo, J.: A micro-mechanically based continuum damage model for carbon black-filled rubbers incorporating Mullins effect. J. Facade Des. Eng. 39, 87–112 (1991)

Guo, Z., Sluys, L.J.: Computational modelling of the stress-softening phenomenon of rubber-like materials under cyclic loading. Eur. J. Mech. A. Solids 25(6), 877–896 (2006)

Hagl, A., Dieterich, O., Wolf, A.T., Sitte, S.: Tensile loading of silicone point supports-revisited. Chall. Glass 3, 235–247 (2012)

Houwink, R.: Slipping of molecules during the deformation of reinforced rubber. Rubber Chem. Technol. 29, 888–93 (1956)

International Organization for Standardization.: ISO 37-Rubber, vulcanized or thermoplastic—determination of tensile stress–strain properties (2011)

Kraus, G., Childers, C.W., Rollman, K.W.: Stress softening in carbon black reinforced vulcanizates. Strain rate and temperature effects. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 10, 229–240 (1966)

Marckmann, G., Verron, E.: Comparison of hyperelastic models for rubber-like materials. Rubber Chem. Technol. 79(5), 835–858 (2006)

Marlow, R.S.: A general first-invariant hyperelastic constitutive model. In: Constitutive Models For Rubber-Proceedings, pp. 157–160 (2003)

Mars, W.V.: Evaluation of a pseudo-elastic model for the Mullins effect. Tire Sci. Technol. 32(3), 120–145 (2004)

Miehe, C.: Discontinuous and continuous damage evolution in Ogden-type large-strain elastic materials. Eur. J. Mech. A Solids 14, 697–720 (1995)

Mooney, M.: A theory of large elastic deformation. J. Appl. Phys. 11(9), 582–592 (1940)

Mullins, L.: Softening of rubber by deformation. Rubber Chem. Technol. 42(1), 339–362 (1969)

Ogden, R.W., Roxburgh, D.J.: A pseudo-elastic model for the Mullins effect in filled rubber. Proc. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 455, 2861–2877 (1999)

Ogden, R.W., Saccomandi, G., Sgura, I.: Fitting hyperelastic models to experimental data. Comput. Mech. 34(6), 484–502 (2004)

Overend, M., Nhamoinesu, S., Watson, J.: Structural performance of bolted connections and adhesively bonded joints in glass structures. J. Struct. Eng. 139(12) , 04013015-1–04013015-12 (2013). https://ascelibrary.org/doi/pdf/10.1061/%28ASCE%29ST.1943-541X.0000748

Peeters, F., Kussner, M.: Material law selection in the finite element simulation of rubber-like materials and its practical application in the industrial design process. In: Constitutive Models for Rubber: Proceedings of the First European Conference on Constitutive Models for Rubber, pp. 29–36 (1999)

Qi, H.J., Boyce, M.C.: Constitutive model for stretch-induced softening of the stress-stretch behavior of elastomeric materials. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 52(10), 2187–2205 (2004)

Santarsiero, M., Louter, C., Nussbaumer, A.: Laminated connections for structural glass applications under shear loading at different temperatures and strain rates. Constr. Build. Mater. 128, 214–237 (2016a). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2016.10.045

Santarsiero, M., Louter, C., Nussbaumer, A.: The mechanical behaviour of SentryGlas ionomer and TSSA silicon bulk materials at different temperatures and strain rates under uniaxial tensile stress state. Glass Struct. Eng. (2016b). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40940-016-0018-1

Santarsiero, M., Louter, C., Nussbaumer, A.: Laminated connections for structural glass applications under tensile loading at different temperatures and strain rates. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. (2017). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijadhadh

Santarsiero, M., Louter, C., Nussbaumer, A.: A novel triaxial failure model for adhesive connections in structural glass applications. Eng. Struct. 166, 195–211 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.engstruct.2018.03.058

Simo, J.C.: On a fully three-dimensional finite-strain viscoelastic damage model: formulation and computational aspects. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 60(2), 153–173 (1987)

Sitte, S., Brasseur, M.J., Carbary, L.D., Wolf, A.T.: Preliminary evaluation of the mechanical properties and durability of transparent structural silicone adhesive (TSSA) for point fixing in glazing. J. ASTM Int. 8(10), 1–27 (2011)

Steinmann, P., Hossain, M., Possart, G.: Hyperelastic models for rubber-like materials: consistent tangent operators and suitability for Treloar’s data. Arch. Appl. Mech. 82(9), 1183–1217 (2012)

Sussman, T., Bathe, K.J.: A finite element formulation for nonlinear incompressible elastic and inelastic analysis. Comput. Struct. 26, 357–409 (1987)

Yeoh, O.H.: Phenomenological theory of rubber elasticity. In: Aggarwal, S.L. (ed.) Comprehensive Polymer Science. Pergamon Press, Oxford (1995)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Glas Trösch AG Swisslamex, Dow Corning and Nuova Oxidal for the material support and fabrication of specimens. Furthermore, the assistance and support of all TU Delft Stevin Laboratory members that contributed in preparing and conducting the tests is gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Appendices

Appendix A

Isochoric part - Assumption of incompressibility:

Rubber-like material models are classified into two basic categories based on the expression of the strain energy function. The phenomenological models that provide a mathematical framework for describing the mechanical behaviour of elastomers based on continuum mechanics. The determination of the material parameters is difficult and these models may prove to be inaccurate for large deformations out of the predefined range of the model. Since they are in essence empirical expressions, they lack a physical interpretation (Dispersyn et al. 2017). The physical (or micro-mechanical) models that are based on physics of polymer chains and on statistical and kinetic theory. These models derive elastic properties from an idealized model of the structure (Guo and Sluys 2006). The strain energy function is formed based on microscopic phenomena. This study focuses on phenomenological models and compares the performance of the Mooney–Rivlin (with 2 or 3 parameters), Neo–Hooke, Yeoh and Gent–Thomas models.

Mooney–Rivlin

In the work of Marckmann and Verron (2006), the Mooney–Rivlin theory is considered appropriate for rubbers exhibiting moderate deformations (lower than 200%). The strain energy function of this model is

where \(\hbox {C}_{10}\) and \(\hbox {C}_{01}\) are the material parameters (Dispersyn et al. 2017; Mooney 1940).

Neo–Hooke

The Neo–Hookean hyperelastic model is a special case of the Mooney–Rivlin model, where \(\hbox {C}_{01}\) is equal to zero and thus the strain energy function depends only on the first invariant \(\hbox {I}_{1}\) (Dispersyn et al. 2017). It is the simplest hyperelastic model and it is applicable in cases when few test data are available (Dispersyn et al. 2017). Even though a single test is needed to determine the material response, the model is not able to accurately describe the behaviour in other modes such as other multi-parameter models; however, it can still provide a good approximation (Ali et al. 2010; Marlow 2003). In addition, due to its simplified formula, this model does not accommodate differences in curvature and therefore cannot describe an S-shaped stress-deformation diagram. According to Steinmann et al. (2012) the model describes experimental data fairly accurate for small deformations(\(\lambda )\) in uniaxial tension and simple shear up to 1.5 and 1.9, respectively. The strain energy function of the Neo-Hooke model is:

Yeoh

This model is suitable to describe large deformations (Dispersyn et al. 2017) and predicts the stress–strain behaviour of different deformation states from test data coming only from uniaxial tension data (Peeters and Kussner 1999). However, the performance of the Yeoh model at low strains must be carefully examined (Yeoh 1995). The mathematical expression of the Yeoh models is

Gent–Thomas

The phenomenological model proposed by Gent and Thomas (1958) has the same material constants as the Mooney–Rivlin model, with the only difference that the natural logarithm is included in the second term. Since it does not include higher terms of \(\hbox {I}_{1}\), it is not suitable for predicting large deformations (Dispersyn et al. 2017), as the Yeoh model, but it is considered fairly accurate at small strains. The strain energy function of the Gent–Thomas model is

Volumetric part - Extension to compressibility:

In literature, one can find several models that describe volumetric changes of rubbers and which are expressed as a function of the jacobian, J, of the deformation gradient tensor. These models consist of a single material constant which is the bulk modulus, K, of the adhesive. In order to properly define the bulk modulus of rubbers, oedometric test are needed (Dias and Odenbreit 2016). An oedometric test requires inserting a piece of the adhesive, often a circular specimen, inside a rigid matrix in order to achieve a perfectly confined state by fully restraining lateral expansion. Subsequently, the upper part of the adhesive is compressed with the help of a piston in order to impose a hydrostatic stress state to the adhesive. During this process, stress and strain data are kept for the determination of the bulk modulus. The most common material model that accounts for compressible behaviour is expressed by Sussman and Bathe (1987) and is

Appendix B

Most finite element software make use of pseudo-elastic material models to describe stress-softening phenomena of elastomers. Pseudo-elastic models use the theory of pseudo-elasticity to describe the loading path with a common strain energy function and the unloading and reloading paths with a different strain energy function that is based on the undamaged situation.

Ogden–Roxburgh

The most commonly used model in finite element codes that considers cyclic stress-softening effects is based on the generalization of the Ogden and Roxburgh model (Ogden and Roxburgh 1999) proposed by Mars (2004). This model introduces a scalar variable \(\upeta \) that ranges between 0 and 1. This variable represents the damage caused by the Mullins effect. In the undamaged situation (\(1{\mathrm{st}}\) loading) \(\upeta \) is equal to 1. It must be noted that this variable does not affect the hydrostatic (volumetric) part of the strain energy function, because volume variations are very small.

where m and r, material constants, m, r > 0; b, a positive material parameter, 0 \(\le \) b \(\le \) 0.5; erf, the error function; \(\hbox {W}_{\mathrm{m}}\), the previously maximum energy encountered.

Guo

The Ogden–Roxburgh model can only describe situations that approach the “ideal Mullins effect”, where the unloading and reloading response follow the same path. In cases of diverging loading and reloading responses, a second class of models is defined. To this day, these models are not supported by finite element codes, unless they are considered via a user defined subroutine. Models accounting for this divergence of the loading and reloading paths have been developed by Miehe (1995) and Besdo and Ihlemann (2003). Recently, a damage model based on the theory of pseudo-elasticity was proposed by Guo (Guo and Sluys 2006).

Unloading branch:

where \(\hbox {W}_{0}\), strain energy of the undamaged material; \(\hbox {W}_{00}\), strain energy at the origin in the stress-free state; \(\upeta _{\mathrm{m}}\), the minimum value of the damage variable.

Reloading branch:

Where:

- \(\hbox {m}_{1}\) and \(\hbox {r}_{1}\):

-

material constants, m, r > 0

- \(\hbox {W}_{\mathrm{mr}}\) :

-

the strain energy when the material is again subjected to loading (assume 0)

Appendix C

Static tests

Cyclic tensile tests—0.1 Hz

3 consistent tests: TSSAC 158, TSSAC 159, TSSAC 189

1 non-consistent test: TSSAC 120

1 unsuccessful test: specimen failed during cyclic loading (considered non-representative): TSSAC 134

Cyclic tensile tests—1 Hz

Cyclic shear tests—0.1 Hz one direction shear

Cyclic shear tests—0.1 Hz two direction shear

Cyclic shear tests—1 Hz two direction shear

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ioannidou-Kati, A., Santarsiero, M., de Vries, P. et al. Mechanical behaviour of Transparent Structural Silicone Adhesive (TSSA) steel-to-glass laminated connections under monotonic and cyclic loading. Glass Struct Eng 3, 213–236 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40940-018-0066-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40940-018-0066-9