Abstract

Sexual strategies theory indicates women prefer mates who show the ability and willingness to invest in a long-term mate due to asymmetries in obligate parental care of children. Consequently, women’s potential mates must show they can provide investment – especially when women are seeking a long-term mate. Investment may be exhibited through financial and social status, and the ability to care for a mate and any resulting offspring. Men who care for children and pets (hereafter “dependents”) are perceived as high-quality mates, given that dependents signal an ability to invest; however, no studies have examined how dependents are associated with short-term and long-term mating strategies. Here, online dating profiles were used to test the predictions that an interactive effect between sex and mating strategy will predict displays of dependents, with long-term mating strategy predicting for men but not women. Moreover, this pattern should hold for all dependent types and, due to relative asymmetries in required investment, differences will be strongest regarding displays of children and least in non-canine pets. As expected, men seeking long-term mates displayed dependents more than men seeking short-term mates, but both men and women seeking long-term mates displayed dependents similarly. This pattern was driven mostly by canines. These findings indicate that men adopting a long-term mating strategy display their investment capabilities more compared to those seeking short-term mates, which may be used to signal their mate value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Evolutionary theories about mating behavior highlight sex-specific preferences, interest, strategies, and choices which largely stem from different challenges and opportunities that each sex faces in relation to their obligatory parental investment (Buss, 1989; Trivers, 1972). Women invest more in terms of metabolically expensive egg production, a relatively small number of viable ova, gestation and lactation, which results in a more limited reproductive potential than men (Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Clutton-Brock & Scott, 1991; Trivers, 1972). In contrast, men’s obligatory investment is far smaller, and instead their reproductive potential is limited by access to mates (Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Trivers, 1972). Male investment can involve the provision of emotional and physical care for offspring, as well as resources such as financial stability and social status (Buss & Schmitt, 1993, 2016). Paternal provisioning may increase the likelihood of offspring survival and subsequent reproduction (Clutton-Brock & Scott, 1991) and helps reduce a woman’s inter-birth interval (Szabó et al., 2017), allowing her to produce more children and increase the reproductive success of both parents in a monogamous system (Buss, 1989; Buss & Schmitt, 2016; Clutton-Brock & Scott, 1991).

Sexual strategies theory (SST) refers to long- and short-term mating strategies used by both sexes, as influenced by differences in parental investment (Buss & Schmitt, 1993, 2016). Long-term mating strategies are characterized by commitment and biparental investment, while short-term mating strategies are typified by brief affairs with multiple mates resulting in minimal investment in mates and, for males at least, offspring (Buss & Schmitt, 1993, 2016). According to Buss and Schmitt (1993), men tend toward short-term mating while women tend to prefer long-term mates. As predicted by SST, the conjecture that women prefer men who can provide investment (e.g., resources) has been demonstrated in laboratory experiments (Brase, 2006; Dunn & Hill, 2014; Dunn & Searle, 2010; Thomas & Stewart-Williams, 2018) and observational studies involving speed-dating (Asendorpf et al., 2011), “traditional” dating (Gray et al., 2015), and personal advertisements (Jagger, 1998; Gonzales & Meyers, 1993; Butler-Smith et al., 1998; Bereczkei et al., 2010; Strassberg & English, 2014), including online dating platforms (Gallant et al., 2011; Guadagno et al., 2012; Hitsch et al., 2010; Ingram et al., 2019; Toma et al., 2008).

Female Expectations of Investment

When adopting a short-term mating strategy, women evaluate male traits that will offset the costs of raising offspring alone because of fundamental differences in parental investment. In this context, females seek direct benefits from short-term mates such as immediate financial gains and social status (Buss & Schmitt, 2016; Greiling & Buss, 2000). For example, Buss and Schmitt (1993) showed that females assessed frugal men as unattractive and preferred potential mates who were willing to give gifts early in their encounters. By contrast, women adopting a long-term mating strategy prefer traits of a good companion—and potentially good parent—including love, kindness, agreeableness, and skills necessary for raising a child (Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Jackson & Kirkpatrick, 2007; Li & Kenrick, 2006). For instance, women select altruistic men as their ideal choice when faced with multiple potential long-term mates (Norman & Fleming, 2019). Indeed, even women’s acceptance of a date increases when a man has indicators of high financial and social status (Guéguen & Lamy, 2012).

Dependents as Displays of Male Investment Capacity

Dependents (i.e., alive beings who depend on someone for care: Serpell & Paul, 2011; such as children: Belk, 1988; or pets: Sanders, 1990) may serve as a signal of an ability and willingness to provide resources and care—or investment capacity—for individuals seeking mates. Such cues are especially salient for men, such that men with children (Guéguen, 2014; Roney et al., 2006) and pets (Gray et al., 2015; Tifferet et al., 2013) are seen as being more attractive mates than those without. This can occur because children and canine pets may indicate high financial and social status, as well as caring abilities (Beverland et al., 2008; Kemkes, 2008; Mosteller, 2008; Serpell & Paul, 2011; Tifferet et al., 2013). In addition, children and canine pets require significant material investment (Corso, 2007; Mosteller, 2008; Prendergast & Wong, 2003) and are highly social beings (Maleki et al., 2019; Zasloff, 1996). Other types of pets (such as felines) require less care and social interaction (Gray et al., 2015; Kogan & Volsche, 2020; Zasloff, 1996), and thus might not be as strong a signal of male investment.

Mating Strategies, Dependents, and Online Dating

Online dating has become increasingly popular in the past two decades, leading to a growth of research regarding how it affects human mating behavior (Finkel et al., 2012). Researchers have examined how individuals display their own physical traits (Gallant et al., 2011; Gonzales & Meyers, 1993; Ingram et al., 2019; Toma et al., 2008; Whitty, 2008), as well as external displays (Dawson & McIntosh, 2006), which includes children (Butler-Smith et al., 1998; Kisilevich & Last, 2010; Lin & Lundquist, 2013) and pets (Gray et al., 2015; Ingram et al., 2019). Findings have typically supported SST; on personal advertisements, men display traits relevant to their ability to accrue and provide finances, status, and care, while women display physical attractiveness (Jagger, 1998; Dawson & McIntosh, 2006; Gallant et al., 2011; Gray et al., 2015; Kogan & Volsche, 2020; also see Abramova et al., 2016 for review). Moreover, the previous work reviewed has largely ignored how pets and children are displayed under naturalistic mating contexts. Thus, the goal of the current research is to address how dependents are used as advertisements of mate quality in online dating. Dependents signal parental abilities, but also correlate with other traits of high-value mates; thus, it is expected that sex- and strategy-specific differences exist in terms of how they are presented on dating profiles.

This study will investigate this issue in two ways. First, how pets and children (under the banner of “dependents”) are displayed will be examined. Past findings have indicated that men are expected to show they can provide investment to a mate and resulting offspring, especially when adopting long-term mating strategies (e.g., material goods, time, and status; Buss & Schmitt, 1993). Thus, men should display dependents more than women, and should display them the most under long-term mating contexts (i.e., compared to those facing lower demands from potential mates regarding investment capacity). Thus, we would expect an interactive effect of sex and mating strategy to predict displays, whereby there is a difference in displays of dependents between sexual strategies for men, but not for women. (Unfortunately, our population did not have a sufficient number of women seeking short-term mates, and thus, we present pairwise predictions to compare sexual strategies in men, and between-sex differences for those seeking long-term mates). We tested the following between-mating strategy predictions:

-

a.

Men adopting a long-term mating strategy will be more likely to have a dependent present on their dating profiles than men adopting a short-term mating strategy.

-

b.

Men adopting a long-term mating strategy who display a dependent will display them with higher frequency on their dating profiles than men adopting a short-term mating strategy.

We also propose two between-sex predictions:

-

a.

Men adopting a long-term mating strategy will be more likely to have a dependent present on their dating profiles than women adopting a long-term mating strategy.

-

b.

Men adopting a long-term mating strategy who display a dependent will display them with higher frequency on their dating profiles than women adopting a long-term mating strategy.

Second, the types of dependents displayed were categorized into three groups: children, canines, and other pets (e.g., felines, rodents, and birds) to explore whether types of dependents may be displayed with different frequency depending on mating strategy and sex, given the categories vary with the level of investment and time commitment. Given this, we can expect that the pattern will match the previous predictions (regarding dependents in general); however, given the relative investment required for the different types of dependents, we expect that the difference between groups will be largest for children, moderate for canines, and weakest for other pets.

Methods

Data Collection

Between July and August 2020, two free accounts (one male and one female) on an online dating platform were created. The platform is popular in Canada, and profiles contain a wealth of information about a user (users are encouraged—but not forced—to discuss a multitude of facets regarding their family, occupational, and personal lives during profile construction).

The account was used to access profiles of the opposite-sex, with the search function used to set parameters for the selection of subjects—hereafter referred to as “daters”. The age of potential daters was left unrestricted. Daters were categorized according to the type of connection they sought. They could indicate they were seeking a long-term relationship or a casual encounter with no commitment; these designations were used as proxies for mating strategies, with the former defined as a long-term mating strategy, and the latter a short-term mating strategy.

Daters were then filtered by geographic location so that all were situated in Nova Scotia, Canada. Given that this study was performed during the SARS-COV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic, we sampled this province because of its relatively low and consistent case numbers compared to other parts of the country (see Public Health Agency of Canada, 2021). Every second profile was selected to systematically increase the coverage of daters if the platform sorted profiles by similarity to our constructed profiles (e.g., by proximity or age). Information from selected profiles was recorded as long as it contained photographs of the individual—those with generic photos (i.e., quotes, stock photos of animals, nature scenes without a person), as well as spam accounts (e.g., profiles advertising spam websites) and profiles whose connection (i.e., “mating strategy”) was unclear (e.g., profiles “seeking a relationship” but also indicated elsewhere they wanted to find “friends” or “something casual”) were ignored. If a profile did not fit these criteria, then the next profile that did was recorded.

The resulting sample comprised of 225 men and 225 women who were seeking a relationship, and 225 men who were not seeking a relationship (N = 721). For the sake of completeness, women who were not seeking a relationship were also sampled; only 46 of these women had profiles on the platform in Nova Scotia (i.e., 2019 provincial population size estimate 969,747; Government of Nova Scotia, 2020). Though no a priori predictions were made regarding these women, they have been included in analyses found in the Appendix.

Dater mating strategy and sex was recorded. Their displays of dependents were quantified based on photographs or written statements indicating the type of dependent: children, dogs and/or pets (i.e., cats and others such as birds and rodents) were in the care of the dater. Lastly, age, education level, and whether the dater wanted children were documented (see Table 1).

Displays of Dependents: Statistical Analyses

To test our predictions, dependents were categorized as a binary, categorical variable based on whether daters indicated that they had children or pets (hereon called “presence”). Then, for daters who indicated a dependent, the frequency with which dependents were displayed was recorded by tallying the number of times they were present (hereon called “frequency”). For example, a profile with a picture containing the dater and two dogs, as well as an indication they had two dogs in the description would be assigned four points, whereas a separate profile with only a picture or description of a cat—with no reference to it in the description or a picture, respectably—would be assigned one.

Generalized linear models were used to assess the effect of sex and mating strategy on the presence and frequency of dependency displays. Binary variables (i.e., presence/absence of dependents) were modeled using a binomial distribution, while counts of dependents followed a Poisson distribution. Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used to assess which model best fit the data. We ranked all possible predictors of dependents for each model; these included the influence of dater’s mating strategy for the between mating strategy comparison, and the dater’s sex for the between sex comparison. Conventionally, models whose AIC value is the lowest and has a difference greater than two compared to the next lowest model is the best fit to the data and holds significant predictive value (Akaike, 1974). Post hoc comparisons were performed using least squared means. Statistical tests were performed using RStudio, version 1.3.959 (R Core Team, 2020).

Displays of Dependent Types: Statistical Analyses

To explore the potential for mating strategy or sex to influence the types of dependents that are displayed on dating profiles, we examined a subset of data including only those daters who showed at least one dependent on their profiles. For this analysis, AIC was used again to investigate the interactive effect of either mating strategy or sex and dependent type on the frequency with which dependents (children, dogs, or other pets) were displayed. As these are count data, we used a Poisson error distribution for our models. We used frequencies only in this analysis, rather than proportion displaying, as the subset captured the daters who did not display one or two of the three types of dependents. Assessment criteria were the same as for other models. Again, statistical tests were performed using RStudio, version 1.3.959 (R Core Team, 2020).

Results

Total Displays of Dependents

Men: Between Mating Strategy Comparison

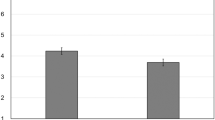

For the between-mating strategy comparison of men adopting long- and short-term strategies, a dependent was significantly more likely to be present on the profiles of the former than the latter (84.44% and 53.78% displayed, respectively; Table 2, Fig. 1a). For daters who displayed a dependent, we examined the frequency of these displays. A similar pattern emerged; men adopting a long-term strategy displayed dependents at a significantly higher frequency (M = 2.19, SD = 1.29) than those pursuing a short-term approach in their profiles (M = 1.59, SD = 0.98; see Table 2, Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1 Between-mating strategy comparison: influence of male dater’s mating strategy on the displays of dependents on dating profiles; asterisks denote significant difference between comparison (ΔAICC ≥ 2). (a) Comparison of proportion of daters with dependent present on their profile; vertical lines denote 95% confidence interval. (b) Comparison of daters who displayed a dependent regarding the frequency of such displays; plot thickness proportional to density of corresponding y-values, diamonds denote mean, dots denote median

Long-Term Mating Strategy: Between Sex Comparison

For the between-sex comparison of men and women adopting a long-term mating strategy, both men and women were equally likely to have a child or pet present on their profile (88.44% of women displayed; Table 2, Fig. 2a). Additionally, when examining the frequency of displayed dependents, there was no difference between men and women (M = 2.01, SD = 1.17) adopting a long-term strategy (see Table 2, Fig. 2b).

Between-sex comparison: influence of sex regarding daters adopting long-term mating strategies on the displays of dependents on dating profiles; asterisks denote significant difference between comparison (ΔAICC ≥ 2). (a) Comparison of proportion of daters with dependent present on their profile; vertical lines denote 95% confidence interval. (b) Comparison of daters who displayed a dependent regarding the frequency of such displays; plot thickness proportional to density of corresponding y-values, diamonds denote mean, dots denote median

Types of Dependents

Men: Between-Mating Strategy Comparison

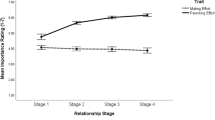

Both mating strategy and type (children, dogs, or other pets) influenced the total number of displays of dependents (see Table 3). Within males, our model selection process revealed an ambiguous result between an additive and interactive relationship; nevertheless, we discuss some important post hoc comparisons here. First, men using a long-term mating strategy showed dogs (M = 0.86, SD = 1.08) at a higher frequency than those using short-term mating strategies (M = 0.54, SD = 0.88; see Fig. 3a). Second, men adopting a long-term strategy showed children (M = 0.79, SD = 0.97) and dogs more than other pets on their dating profiles (see Fig. 3a). No such differences were found between short-term oriented men; they displayed children (M = 0.55, SD = 0.71), dogs, and other pets (M = 0.50, SD = 0.58) with similar frequency (see Fig. 3a).

Fig 3. Asterisks denote significant difference between comparison, diamond denotes mean, dot denotes median. (a) Between-mating strategy comparison: influence of male dater’s mating strategy on the displays of dependent types on dating profiles. (b) Between-sex comparison: influence of sex regarding daters adopting a long-term mating strategy on the displays of dependent types on dating profiles

Long-Term Mating Strategy: Between-Sex Comparison

For daters adopting a long-term mating strategy, patterns differed between the sexes (Table 3). Men described or showed photos of dogs with higher frequency than women (see Fig. 3b). Furthermore, women tended to show children more frequently (M = 0.93, SD = 0.73) than either type of pet (dog: M = 0.50, SD = 0.87; other pets: M = 0.59, SD = 0.71; see Fig. 3b). Moreover, pets such as cats were displayed less than children and canines by men—there was no difference in the frequency with which the latter were displayed (Fig. 3b).

Analysis only includes daters who displayed a dependent on their dating profile. AICC is the Akaike information criterion value, ΔAICC is the change in relation to the lowest AICC, ωAICC is the relative predictive power of each model compared to all other models. The best model differs from others by ΔAICC of 2 or greater and are shown in bold; if less than 2, both models had similar predictive power.

Discussion

To begin, it should be noted that few women in our population declared interest in a short-term mate, which is consistent with previous work (e.g., Buss & Schmitt, 1993) as, due to differences in obligate parental investment, women tend toward a long-term mating strategy while men tend to seek short-term mates. This finding suggests that men’s mating strategies may be more flexible relative to women’s strategies. Also, it points to the need for future research on relationships, given Schacht and Borgerhoff-Mulder (2015) found that men and women reported being equally interested in short-term mating.

Displays of Dependents

We supported our predictions regarding the display of dependents as influenced by mating strategies. Men who were seeking long-term mates displayed dependents on their profiles significantly more than men seeking short-term mates. Men seeking long-term relationships may show dependents as a way of advertising their parenting abilities and willingness to provide resources, which align with women’s mate preferences (e.g., Bereczkei et al., 2010; Buss & Schmitt, 1993; Li & Kenrick, 2006). These preferences are generally stronger in women when seeking long-term relationships, as compared to women adopting short-term mating strategies, who tend to place a greater importance on physical attractiveness (Li & Kenrick, 2006, see also humor and sociability: Mehmetoglu & Määttänen, 2020) rather than resource and care provisioning (Buss & Schmitt, 1993).

These results show evidence of cross-sex mind-reading. Geher (2009) posits that it is advantageous for heterosexual individuals to determine the mate preferences of potential mates and then advertise those desired features. Cross-sex mind-reading may be a form of mating intelligence, whereby one anticipates what potential mates desire, leading to more successful courtship. Geher (2009) proposes that there are different types of cross-sex mind-reading that are relevant here: men’s ability to know the short- and long-term preferences of women, and women’s ability to know the short- and long-term preferences of men. His findings largely indicate that of these four types, the most accurate form is men reading women’s long-term preferences. His reasoning is that, “given the notoriously discriminating nature of females’ choices in mate selection…coupled with strong tendencies for females to pursue long-term mating strategies…there may be particularly strong pressure on males to ‘get it right’ when it comes to long-term desires of females” (p. 344). This study’s findings align well with those of Geher (2009), as well as his explanation. That is, men may be showing dependents when seeking a long-term mate because they know that women prefer men who show these abilities in this relationship context.

Predictions regarding the between-sex comparisons were, however, not supported: men and women seeking long-term mates displayed dependents in a similar fashion. The types of investment dependents may signal regarding their carer are irrelevant to men, apart from caring abilities: qualities of a good parent are valued by men seeking long-term mates (e.g., Jackson & Kirkpatrick, 2007) to maximize return (in terms of reproductive success) of their investment (e.g., Buss & Schmitt, 1993). Consequently, women may be displaying their dependents to advertise their caring abilities to entice men into a long-term commitment (i.e., cross-sex mind-reading; Geher, 2009). This explanation is supported by Goetz (2013), who showed women seeking long-term mates were more likely to present indicators of their parenting abilities than women seeking short-term mates, and compared to men seeking any mate, in their online personal advertisements.

Displays of Dependent Types

How daters displayed their dependents varied by type (e.g., canine, feline), though our prediction was unsupported: not only did the pattern in which children, canines, and other pets were displayed differ, but the magnitude of between-group differences was similar. However, the results do paint an informative picture; different dependents have specific qualities about them that may explain our findings.

Children were among the most frequently displayed dependents by men seeking long-term mates. Such findings are logical as Kemkes (2008) showed men pictured with children are perceived as having elevated financial and social status, as well as parenting abilities. Men enjoy this elevation of perceived status as children in Canada take, on average, roughly $250,000 to raise to adulthood (Brown, 2015), and financial status is linked with social standing, thus making them an indicator of their parent’s ability to accrue and provide financial resources (on top of caring abilities). Moreover, such investment is strongly desired by women seeking long-term mates (e.g., Buss & Schmitt, 1993), which could explain these men’s propensity to display them so frequently. Children were also the most frequently displayed dependent on the profiles of women seeking long-term mates. Children require considerable care, which mothers typically provide more than fathers (e.g., while their partners performed childcare on non-workdays, fathers engaged in leisure activities 47% of this time: Kamp Dush et al., 2017), making them strong signals of a woman’s caring abilities (Kemkes, 2008). Furthermore, women are presumably most likely to display a child given 80% of separated Canadian women have primary custody of their children (Government of Canada, 2015). Therefore, women may be using children to showcase their caring abilities (as men seek qualities of a good parent in long-term mates: Buss & Schmitt, 1993), to honestly inform a prospective mate of her current familial situation, or even to signal fecundity if said dater was in her reproductive prime.

Next, on the profiles of long-term oriented men, canines (alongside children) were the most frequently displayed dependent, significantly more than men seeking short- and women seeking long-term mates. This pattern follows our between-strategy and between-sex predictions and was likely the main driver of the results for dependents in general. Some studies have suggested canines are a strong signal for a male’s investment capacity and masculinity (Gray et al., 2015; Kogan & Volsche, 2020; Mitchell & Ellis, 2013; Tifferet et al., 2013), as well as dominance-related qualities (Alba & Haslam, 2015, which is also sought by women: Buss & Schmitt, 1993). The types of investment that canines signal in a male carer (i.e., social and financial status, caring abilities) are sought more by women under long-term mating contexts than short-term ones, which could explain the inclination for long-term oriented males to display them over short-term ones. This conjecture is largely supported by Tifferet et al., (2013) who found perceived dog ownership improves men’s value as long-term mates in the eyes of women. Men adopting a long-term mating strategy also displayed canines more than women adopting a long-term mating strategy. Again, this can be interpreted as men showing they can provide investment to court women which is more relevant to them than it is to men (e.g., Buss & Schmitt, 1993).

Finally, other pets—this variable mainly comprised of cats—were displayed infrequently. Men’s hesitancy to display them may in part be explained through the findings of Mitchell and Ellis (2013): men show awareness of Western perceptions of feline-ownership being more feminine, which has negative social connotations for men and may not be a trait that women seek in a potential mate (Kogan & Volsche, 2020). Moreover, if non-canine pets are weak signals of their carer’s investment capacity (as they require minimal investment), neither sex would be inclined to display them to attract a mate, which could also explain the lack of difference regarding the between-sex comparison.

Future Work and Limitations

Future work could continue to use SST to predict human behavior in naturalistic settings such as online dating profiles. Such contexts are important as they allow researchers to examine behavior that is difficult to manipulate in the laboratory and findings are more generalizable to the public (Leichsenring, 2004). Because mating motivates human behavior and cognition (Jones et al., 2013; Miller & Maner, 2011), which develop through evolutionary forces (Buss & Schmitt, 1993), understanding how humans show that they are a valuable mate can further our understanding of the underlying drives for these processes.

As an immediate next step, future research could explore whether daters who show dependents are more successful in attracting a mate. This could be done by analyzing the number of profile-clicks or time spent observing a profile by prospective mates. Such findings could support the idea that dependents are honest signals of their carer’s investment capacity if sex- and mating strategy-specific differences are found. Additionally, to support (or weaken) the argument regarding pets as signals of caring abilities, whether people with pets make better parents should be examined.

This study was also conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Though one would think this level of environmental danger could influence human mating strategies (e.g., mate selection criteria become relaxed during times of increased species mortality; Reeve et al., 2016), we do not think this played a role in our findings as sampling occurred after a sharp decrease in viral presence, resulting in restrictions on social movements being relaxed (Nova Scotia’s weekly percent positivity per 100,000 population was between 0.0 and 0.2, rest of Canada between 0.8 and 1.1; see Public Health Agency of Canada, 2021). However, we procured two other samples in the late fall of 2020 which saw a resurgence of cases and intend to collect more samples as the pandemic continues. We hope to use these data to analyze whether a global pandemic influences how men (and women) display their investment capacity (i.e., via dependents) in an online mating context.

There are two main limitations of this study. First, daters were assumed to adopt a certain mating strategy according to their intent for online dating. Though online presences permit an opportunity for deceitful self-representation, dishonest advertisement decreases as the probability of meeting increases in mating contexts (Finkel et al., 2012; Gibbs et al., 2006; Guadagno et al., 2012). Overall, it was assumed daters were relatively honest in their profile construction as their indicated reasons for being on the platform implied a future meeting with a prospective mate. Haselton et al., (2005) showed that women, more than men, report previous long-term mates misconstrued their mating intentions to coerce a sexual encounter. If this was the case in this study, we would have incorrectly categorized men adopting a short-term mating strategy as adopting a long-term mating strategy which could have produced artificial (or hidden) differences between groups if these men were or were not displaying dependents. For a more accurate understanding of a dater’s true intentions, daters could be assessed using the Sociosexual Orientation Inventory (for example, see Jackson & Kirkpatrick, 2007) to determine whether daters leaned toward short-term or long-term mating, before recording their profile’s content. Overall, using SST to predict how people display their mate value on dating profiles is a valuable avenue of exploration, given individuals are seeking mating arrangements which reflect the need for physical encounters.

Second, the age of daters was left unrestricted. Age influences mating behaviour as it correlates with fertility (Conroy-Beam & Buss, 2019): with an increase in age, women’s fecundity decreases more sharply than men’s reproductive potential (Hill & Hurtado, 1991). Consequently, motives for mating change with age as well (McWilliams & Barrett, 2012): older women report seeking younger companions who can provide an active social life—rather than resources—and feel obliged to be a caretaker in later life. Men also seek out younger mates with caregiving abilities. Therefore, how these motives influence how middle- and later-aged individuals present their mate value in mating arenas deserves future consideration. For example, an extension of the current work may entail examining how daters in their reproductive prime, as well as those pre- and post-reproductive prime, display their dependents on an online dating platform.

Conclusion

Our study highlights an important yet overlooked way that people may signal their parenting ability in online dating. The inclusion of dependents represents a way for daters to advertise that they can, and are willing to, invest in a living being. We found that men seeking long-term mates displayed dependents (i.e., children, dogs, and other pets) on their online dating profiles more than men seeking short-term mates but did so equally when compared to women also seeking long-term mates. Dependents signal their carer’s ability and willingness to provide investment in the form of financial and social status, as well as parental care. This investment is more relevant to mates under long-term mating contexts which can explain these patterns. This pattern seems driven by displays of investment-intensive dependents of canines (but also children). Women seeking long-term mates displayed children more than men, while men displayed them more under long-term than short-term mating contexts, emphasizing the importance of caring abilities. Moreover, canines followed our predictions regarding dependents in general. Our results also highlight that women are generally absent in seeking short-term relationships on online dating sites.

Availability of Data and Material

The data collected over the duration of this work will be uploaded to the Open Science Foundation (https://osf.io/uhqa6/).

Code Availability

The code for data analysis can be found at https://osf.io/uhqa6/https://osf.io/uhqa6/.

References

Akaike, H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 19(6), 716–723. https://doi.org/10.1109/TAC.1974.1100705

Alba, B., & Haslam, N. (2015). Dog people and cat people differ on dominance-related traits. Anthrozoös, 28(1), 37–44. https://doi.org/10.2752/089279315x14129350721858

Abramova, O., Baumann, A., Krasnova, H., & Buxmann, P. (2016). Gender differences in online dating: What do we know so far? A systematic literature review. In T. X. Bui & R. H. Sprague Jr. (Eds.), Proceedings of the 49th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Services 2016 (pp. 3858–3867). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2016.481

Asendorpf, J. B., Penke, L., & Back, M. D. (2011). From dating to mating and relating: Predictors of initial and long-term outcomes of speed-dating in a community sample. European Journal of Personality, 25(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.768

Belk, R. W. (1988). Possessions and the extended self. Journal of Consumer Research, 15(2), 139. https://doi.org/10.1086/209154

Bereczkei, T., Voros, S., Gal, A., & Bernath, L. (2010). Resources, attractiveness, family commitment; Reproductive decisions in human mate choice. Ethology, 103(8), 681–699. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0310.1997.tb00178.x

Beverland, M. B., Farrelly, F., & Lim, E. A. (2008). Exploring the dark side of pet ownership: Status- and control-based pet consumption. Journal of Business Research, 61(5), 490–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.08.009

Brase, G. L. (2006). Cues of parental investment as a factor in attractiveness. Evolution and Human Behavior, 27(2), 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2005.06.003

Brown, M. (2015, April 16). The real cost of raising a child. MoneySense. https://www.moneysense.ca/save/financial-planning/the-real-cost-of-raising-a-child/.

Buss, D. M. (1989). Sex differences in human mate preferences: Evolutionary hypotheses tested in 37 cultures. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 12(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x00023992

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual Strategies Theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100(2), 204–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.100.2.204

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (2016). Sexual strategies theory. In T. K. Shackelford., & V. A. Weekes- Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-16999-6_1861-1

Butler-Smith, P., Cameron, S., & Collins, A. (1998). Gender differences in mate search effort: An exploratory economic analysis of personal advertisements. Applied Economics, 30(10), 1277–1285. https://doi.org/10.1080/000368498324896

Clutton-Brock, T., & Scott, D. (1991). The Evolution of Parental Care. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvs32ssj

Conroy-Beam, D., & Buss, D. M. (2019). Why is age so important in human mating? Evolved age preferences and their influences on multiple mating behaviors. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 13(2), 127–157. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000127

Corso, R. A. (2007, December 4). Pets are “members of the family” and two-thirds of pet owners buy their pets holiday presents. Harris Interactive. https://theharrispoll.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Harris-Interactive-Poll-Research-Pets-2007-12.pdf

Dawson, B. L., & McIntosh, W. D. (2006). Sexual strategies theory and Internet personal advertisements. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 9(5), 614–617. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.614

Dunn, M. J., & Hill, A. (2014). Manipulated luxury-apartment ownership enhances opposite-sex attraction in females but not males. Journal of Evolutionary Psychology, 12(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1556/jep.12.2014.1.1

Dunn, M. J., & Searle, R. (2010). Effect of manipulated prestige-car ownership on both sex attractiveness ratings. British Journal of Psychology, 101(1), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712609x417319

Finkel, E. J., Eastwick, P. W., Karney, B. R., Reis, H. T., & Sprecher, S. (2012). Online dating: A critical analysis from the perspective of psychological science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 13(1), 3–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1529100612436522

Gallant, S., Williams, L., Fisher, M., & Cox, A. (2011). Mating strategies and self-presentation in online personal advertisement photographs. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology, 5(1), 106–121. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0099272

Geher, G. (2009). Accuracy and oversexualization in cross-sex mind-reading: An adaptationist approach. Evolutionary Psychology, 7(2), 147470490900700. https://doi.org/10.1177/147470490900700214

Gibbs, J. L., Ellison, N. B., & Heino, R. D. (2006). Self-presentation in online personals. Communication Research, 33(2), 152–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650205285368

Goetz, C. D. (2013). What do women’s advertised mate preferences reveal? An analysis of video dating profiles. Evolutionary Psychology, 11(2), 147470491301100. https://doi.org/10.1177/147470491301100208

Gonzales, M. H., & Meyers, S. A. (1993). “Your mother would like me”: Self-presentation in the personal ads of heterosexual and homosexual men and women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19(2), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167293192001

Government of Canada, D. of J. (2015, January 7). Selected Statistics on Canadian Families and Family Law: Second Edition. Child Custody - Selected Statistics on Canadian Families and Family Law: Second Edition. https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/rp-pr/fl-lf/famil/stat2000/p4.html.

Government of Nova Scotia. (2020). Nova Scotia annual population estimates as of July 1, 2020. Nova Scotia Department of Finance - Statistics. https://novascotia.ca/finance/statistics/news.asp?id=16179.

Gray, P. B., Volsche, S. L., Garcia, J. R., & Fisher, H. E. (2015). The roles of pet dogs and cats in human courtship and dating. Anthrozoös, 28(4), 673–683. https://doi.org/10.1080/08927936.2015.1064216

Greiling, H., & Buss, D. M. (2000). Women’s sexual strategies: The hidden dimension of extra-pair mating. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(5), 929–963. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(99)00151-8

Griskevicius, V., Tybur, J., Sundie, J., Cialdini, R., Miller, G., & Kenrick, D. (2007). Blatant benevolence and conspicuous consumption: When romantic motives elicit costly displays. PsycEXTRA Dataset. https://doi.org/10.1037/e633982013-262

Guadagno, R. E., Okdie, B. M., & Kruse, S. A. (2012). Dating deception: Gender, online dating, and exaggerated self-presentation. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(2), 642–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.11.010

Guéguen, N. (2014). Cues of men’s parental investment and attractiveness for women: A field experiment. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 24(3), 296–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2013.820160

Guéguen, N., & Lamy, L. (2012). Men’s social status and attractiveness: Women’s receptivity to men’s date requests. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 71(3), 157–160. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185/a000083

Haselton, M. G., Buss, D. M., Oubaid, V., & Angleitner, A. (2005). Sex, lies, and strategic interference: The psychology of deception between the sexes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167204271303

Hill, K., & Hurtado, A. M. (1991). The evolution of premature reproductive senescence and menopause in human females. Human Nature, 2(4), 313–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02692196

Hitsch, G. J., Hortacsu, A., & Ariely, D. (2010). What makes you click? Mate preferences and matching outcomes in online dating. PsycEXTRA Dataset. https://doi.org/10.1037/e633982013-148

Ingram, G., Enciso, M. I., Eraso, N., Garcia, M. J., & Olivera-La Rosa, A. (2019). Looking for the right swipe: Gender differences in self-presentation on Tinder profiles. Annual Review of CyberTherapy and Telemedicine, 17. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/5skrd

Jackson, J. J., & Kirkpatrick, L. A. (2007). The structure and measurement of human mating strategies: Toward a multidimensional model of sociosexuality. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28(6), 382–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.04.005

Jagger, E. (1998). Marketing the self, buying an other: Dating in a post modern, consumer society. Sociology, 32(4), 795–814. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038598032004009

Jones, B. C., Fincher, C. L., Welling, L. L. M., Little, A. C., Feinberg, D. R., Watkins, C. D., & DeBruine, L. M. (2013). Salivary cortisol and pathogen disgust predict men’s preferences for feminine shape cues in women’s faces. Biological Psychology, 92(2), 233–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2012.11.014

Kamp Dush, C. M., Yavorsky, J. E., & Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J. (2017). What are men doing while women perform extra unpaid labor? Leisure and specialization at the transitions to parenthood. Sex Roles, 78(11–12), 715–730. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0841-0

Kemkes, A. (2008). Is perceived childlessness a cue for stereotyping? Evolutionary aspects of a social phenomenon. Biodemography and Social Biology, 54(1), 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/19485565.2008.9989130

Kisilevich, S., & Last, M. (2010). Exploring gender differences in member profiles of an online dating site across 35 countries. In M. Atsm, A. Hotho & A. Chin (Eds.), Proceedings of the International Conference on Analysis of Social Media and Ubiquitous Data (pp. 57–87). Spinger. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-23599-3_4

Kogan, L., & Volsche, S. (2020). Not the cat’s meow? The impact of posing with cats on female perceptions of male dateability. Animals, 10(6), 1007. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10061007

Leichsenring, F. (2004). Randomized controlled versus naturalistic studies: A new research agenda. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 68(2), 137–151. https://doi.org/10.1521/bumc.68.2.137.35952

Li, N. P., & Kenrick, D. T. (2006). Sex similarities and differences in preferences for short-term mates: What, whether, and why. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(3), 468–489. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.3.468

Lin, K. H., & Lundquist, J. (2013). Mate selection in cyberspace: The intersection of race, gender, and education. American Journal of Sociology, 119(1), 183–215. https://doi.org/10.1086/673129

Maleki, M., Mardani, A., Mitra Chehrzad, M., Dianatinasab, M., & Vaismoradi, M. (2019). Social skills in children at home and in preschool. Behavioral Sciences, 9(7), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs9070074

McWilliams, S., & Barrett, A. E. (2012). Online dating in middle and later life. Journal of Family Issues, 35(3), 411–436. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x12468437

Mehmetoglu, M., & Määttänen, I. (2020). Norwegian men and women value similar mate traits in short-term relationships. Evolutionary Psychology, 18(4), 147470492097962. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474704920979623

Miller, S. L., & Maner, J. K. (2011). Ovulation as a male mating prime: Subtle signs of women’s fertility influence men’s mating cognition and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(2), 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020930

Mitchell, R. W., & Ellis, A. L. (2013). Cat person, dog person, gay, or heterosexual: The effect of labels on a man’s perceived masculinity, femininity, and likability. Society & Animals, 21(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1163/15685306-12341266

Mosteller, J. (2008). Animal-companion extremes and underlying consumer themes. Journal of Business Research, 61(5), 512–521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2007.07.004

Norman, I., & Fleming, P. (2019). Perceived attractiveness of two types of altruist. Current Psychology, 38(4), 982–990. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00266-1

Prendergast, G., & Wong, C. (2003). Parental influence on the purchase of luxury brands of infant apparel: An exploratory study in Hong Kong. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 20(2), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1108/07363760310464613

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2021, June 22). Government of Canada. Canada.ca. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection.html

R Core Team (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

Reeve, S. D., Kelly, K. M., & Welling, L. L. M. (2016). Transitory environmental threat alters sexually dimorphic mate preferences and sexual strategy. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 2, 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-015-0040-6

Roney, J. R., Hanson, K. N., Durante, K. M., & Maestripieri, D. (2006). Reading men’s faces: Women’s mate attractiveness judgments track men’s testosterone and interest in infants. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 273(1598), 2169–2175. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.3569

Sanders, R. (1990). The animal “other”: Self-definition, social identity, and companion animals. In M. Goldberg, G. Gorn, & R. W. Pollay (Eds.), Advances in Consumer Research (vol 17, pp. 662–668). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

Schacht, R., & Borgerhoff-Mulder, M. (2015). Sex ratio effects on reproductive strategies in humans. Royal Society Open Science, 2(1), 140402. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.140402

Serpell, J. A., & Paul, E. S. (2011). Pets in the family: An evolutionary perspective. Oxford Handbooks Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195396690.013.0017

Strassberg, D. S., & English, B. L. (2014). An experimental study of men’s and women’s personal ads. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(8), 2249–2255. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0428-6

Szabó, N., Dubas, J. S., Volling, B. L., & van Aken, M. (2017). The effect of paternal and alloparental support on the interbirth interval among contemporary North American families. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 11(3), 272–280. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000093

Thomas, A. G., & Stewart-Williams, S. (2018). Mating strategy flexibility in the laboratory: Preferences for long- and short-term mating change in response to evolutionarily relevant variables. Evolution and Human Behavior, 39(1), 82–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2017.10.004

Tifferet, S., Kruger, D. J., Bar-Lev, O., & Zeller, S. (2013). Dog ownership increases attractiveness and attenuates perceptions of short-term mating strategy in cad-like men. Journal of Evolutionary Psychology, 11(3), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1556/jep.11.2013.3.2

Toma, C. L., Hancock, J. T., & Ellison, N. B. (2008). Separating fact from fiction: An examination of deceptive self-presentation in online dating profiles. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(8), 1023–1036. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208318067

Trivers, R. L. (1972). Parental investment and sexual selection. In B. Campbell (Ed.), Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man, 1871–1971 (pp. 136–179). Aldine Press.

Whitty, M. T. (2008). Revealing the ‘real’ me, searching for the ‘actual’ you: Presentations of self on an internet dating site. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(4), 1707–1723. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2007.07.002

Zasloff, R. L. (1996). Measuring attachment to companion animals: A dog is not a cat is not a bird. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 47(1–2), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0168-1591(95)01009-2

Funding

This study was funded in grant held by the second author from the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Mackenzie Zinck: data collection, data analysis, literature review, concept refinement, writing. Laura Weir: data analysis, concept refinement, writing. Maryanne L. Fisher: concept refinement, literature review, writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

As previously stated, we collected data from women who indicated they were not seeking a relationship (i.e., adopting a short-term mating strategy). No a priori predictions were made regarding these women and their sample size (N = 46) was small. We performed the same analysis regarding how these women displayed dependents in relation to the other three comparison groups. Table 4 and Fig. 4 show which model predicted the presence and frequency of displays and between-comparison differences respectively. Table 5 and Fig. 5 show which model predicted the frequency of displays of dependent types and between- as well as within-comparison differences respectively.

Model comparison of the effects of sex and mating strategy, as well as their additive (“ + ”) and interactive (“ × ”) effects on whether or not daters displayed dependents, and the number of such displays on their dating profile of daters who displayed one. AIC is the Akaike information criterion value, ΔAIC is the change in relation to the best AIC, ωAIC is the relative predictive power of each model compared to all other models. The best model(s) differ from others by ΔAICC of 2 or greater and are shown in bold.

Model comparison of the effects of sex and mating strategy, as well as their additive (“ + ”) and interactive (“ × ”) effects on whether or not daters displayed different dependents, and the number of such displays on their dating profile of daters who displayed a dependent. AIC is the Akaike information criterion value, ΔAIC is the change in relation to the best AIC, ωAIC is the relative predictive power of each model compared to all other models. The best model(s) differ from others by ΔAICC of 2 or greater and are shown in bold. Only top 4 models are shown.

Different letters denote significant difference between comparison, diamond denotes mean, dot denotes median. (a) Between-mating strategy comparison: influence of male dater’s mating strategy on the displays of dependent types on POF profiles. (b) Between-sex comparison: influence of sex regarding daters adopting a long-term mating strategy on the displays of dependent types on POF profiles.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zinck, M.J., Weir, L.K. & Fisher, M.L. Dependents as Signals of Mate Value: Long-term Mating Strategy Predicts Displays on Online Dating Profiles for Men. Evolutionary Psychological Science 8, 174–188 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-021-00294-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-021-00294-w