Abstract

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is an inflammatory arthropathy that exhibits heterogeneity in clinical presentation and severity of skin and joint symptoms. This heterogeneity results in an incomplete understanding of the relationship between the skin and joint components of PsA, and their relative impact on PsA disease activity and patient-reported outcomes. The objective of the study was to Investigate the clinical presentation of joint and active skin symptom involvement and the associated impact on physician- and patient-reported outcomes [patient global assessment (PtGA), health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and physical function), and healthcare resource burden in patients with PsA.

Methods

This was a retrospective analysis of the Adelphi 2015 PsA Disease Specific Programme, a real-world, cross-sectional survey of rheumatologists and their consulting PsA patients from the USA and Europe (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and UK). The sample included data collected during the fourth quarter of 2015, on 1201 patients from 410 rheumatologists. Physician-reported joint and active skin symptom involvement were investigated for associations with clinical outcomes, patient/physician-reported outcomes, and healthcare resource utilization (HCRU).

Results

The majority of patients with PsA with documented skin involvement had both joint and active skin involvement (80.9%, njoint+skin = 515, njoint only = 122, noverall = 637). Patients with skin involvement possessed a more severe global clinical profile, and the PsA clinical symptom severity profile positively correlated with skin severity. Physician global assessment scores were not significantly different in patients with joint-only involvement vs. joint with active skin involvement. Patients with skin involvement in PsA possessed significantly worse PtGA scores and increased HCRU.

Conclusion

Patients with PsA involving both joint and active skin symptoms exhibit a more severe overall disease state, worse patient-reported outcomes, and increased HCRU relative to patients with joint-only involvement in PsA. These results indicate that treating skin involvement should be considered along with treating joint involvement in patients with PsA.

Funding

Eli Lilly and Company.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA) is an inflammatory arthropathy characterized by peripheral and/or axial joint inflammation, enthesitis, and dactylitis [1, 2]. Joint symptoms typically present after psoriasis (PsO) skin symptoms, but in some cases PsA is diagnosed before or at the same time as PsO. PsA may also feature skin involvement including nail involvement [3]. In PsA, heterogeneity in clinical presentation and severity of symptoms result in an incomplete understanding of the relationship between the skin and joint components of the disease, and their relative contribution to PsA disease activity and patient-reported outcomes [4].

Correlations between skin and joint symptoms have been investigated in PsA, but conflicting evidence exists in the literature. In a post hoc analysis of baseline clinical trial data from 221 patients with PsA involving at least three joints, Cohen and colleagues identified a weak correlation between the total number of active joints involved (joint tenderness and swelling on a scale of more than 2 points out of 4 points) and body surface area and between the total number of active joints involved and skin severity [5]. In a study of 70 patients with PsA who visited a rheumatology clinic, Elkayam and colleagues [6] identified a significant association between psoriasis area severity index (PASI) and the number of deformed joints. Similarly, Sokoll and Helliwell observed that skin severity (assessed clinically as either mild, moderate, or severe) was associated with HAQ-DI and EQ-5D outcomes in a study involving 47 patients with psoriatic arthritis [7]. Conversely, in a study of 100 patients with PsA who visited a rheumatology clinic, Jones and colleagues [8] observed no association between psoriasis activity (PASI) and joint severity. In this study, peripheral joint disease severity was assessed by counting the number of peripheral joints involved (either clinically or radiographically), as mild (fewer than 10 joints), moderate (10–20 joints), or severe (more than 20 joints) [8]. In an open-label clinical trial involving 1122 patients with PsA, Gottlieb and colleagues [9] also observed no correlations between skin and joint symptoms at baseline as measured by patient global assessment of skin disease and patient-assessed HAQ-DI, respectively. Thus, evidence is conflicting with regards to whether or not a correlation exists between the severity of skin and joint symptoms in PsA. In addition, it is not clear whether the presence of both skin and joint symptoms in PsA has a greater impact on health outcomes and health-related quality of life (HRQoL) than having either symptom alone.

Regardless of whether an association between skin and joint disease severity exists in PsA, the concomitant presence of skin and joint disease may have an added impact on health outcomes and a negative effect on HRQoL. PsA has a negative impact on HRQoL and studies by others [10, 11] indicate that patients with PsA have a poorer quality of life than patients with PsO [12]. Results from clinical trials indicate that skin and joint components of the disease may contribute to patient outcomes, as indicated by observations that the greatest improvements in HRQoL and work productivity are achieved when both skin and joint symptoms improve as a result of treatment [13, 14]. These studies indicate that both the individual skin and joint disease components may contribute to PsA disease severity and patient-reported outcomes. Our objective was to investigate the impact of joint and active skin symptoms in PsA on disease activity, HRQoL, and healthcare-resource utilization (HCRU).

Methods

Study Design

The study was a retrospective, cross-sectional study that used a combination of physician survey, physician-completed medical record data abstraction, and patient survey using the methodology previously published by Anderson and colleagues [15]. The study was conducted in accordance with national market research and privacy regulations (European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act).

Data Source

Data were obtained from the Adelphi PsA Disease Specific Programme and included data obtained in the USA and Europe (France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and UK) from physician surveys, patient record forms (completed by physicians), and patient self-completion questionnaires. Physicians were identified and interviewed as previously published [15]. All responses were anonymized to preserve respondent (physician and patient) confidentiality. Data used for this study were collected in the fourth quarter of 2015.

Patient Selection Criteria and Reporting

Physicians participating in the study must have seen at least three PsA patients per month and have been qualified as a rheumatologist between 1979 and 2012. Participating physicians were asked to report on three consecutive adult patients consulting with a diagnosis of PsA for whom they were actively involved in drug management. Clinical diagnosis of PsA was based upon the rheumatologists’ individual judgment with no restrictions on how the diagnosis was determined for inclusion in the study. Reporting was performed via completion of patient record forms. The patient record form included detailed data on demographic characteristics (including comorbidities), clinical characteristics (including disease timeline, current disease severity, current disease status, current PsA symptoms, presence and severity of PsO, and remission status), clinical outcome measures, treatment patterns, PsA-related HCRU (outpatient visits, assessments and tests conducted, procedures performed within last 12 months). Patients for whom a physician completed a patient record form were asked to fill out a patient self-completion questionnaire, but this was not mandatory and included data on general health, PsA history, PsA symptoms, medications, and patient-reported outcome measures (see below). Patients provided informed consent prior to participating in this study and did not provide any personal identifiable information. As such, formal consent to release information was not required for this study. As a result of the non-interventional nature of the data collection method used in this study, patients were not placed at risk because of participation in the study.

Clinical Outcome Measures

Physicians assessed PsA severity using the physician global assessment (PGA) visual analogue scale (VAS), a 0–100 scale, with 0 being equivalent to the worst possible health assessment. In addition, PsA assessments included joint counts. Psoriasis severity was assessed via the PASI [16] and percentage body surface area (BSA) of psoriasis involvement. Separately, as part of the survey, rheumatologists rated the severity of patients’ current joint and skin severity as either “none”, “mild”, “moderate”, “severe”, or “don’t know” according to their own definition/interpretation of skin severity. PGA, PASI, and BSA assessments were not performed specifically for this study, but as part of usual patterns of clinical practice.

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measures

General HRQoL was assessed using the EuroQoL 5D (EQ-5D)-3L instrument [17]. The EQ-5D VAS served as the patient global assessment (PtGA) in this study and individuals rated their health state on the day of the consultation using the 0–100 scale with 0 being equivalent to the worst possible health state assessment. Physical function was assessed using the health assessment questionnaire disability index (HAQ-DI) [18].

Statistical Analyses

Patients were subgrouped according to whether they had PsA with joint symptoms alone (including patients with no history of psoriasis and those with a history, but no active psoriasis at the time of patient assessment for this study) or joint and active skin symptoms. In addition, for some analyses, patients were further subgrouped according to PsO skin severity (none, mild, moderate, and severe) according to the rheumatologists’ own definition/interpretation of skin severity. The t test was used for pairwise comparisons between two groups with numerical outcomes. Pairwise comparisons between two groups with dichotomous or categorical outcomes utilized Fisher’s exact test or the chi-squared test, respectively. Relationships between skin severity and characteristics of PsA and were investigated using Spearman’s rank correlation. To account for potential joint effects, propensity score matching (PSM) was applied to a number of outcomes with patients from each group matched on the basis of the number of affected joints to determine if the effect was independent of joint involvement. Multivariable regression analyses were utilized to investigate the relationship between outcomes (dependent variable) and skin severity independent of the number of affected joints. Independent variables for the regression analyses were skin severity and the number of affected joints. Regression analyses p values were based upon the skin severity variable. All tests were performed with a significance level of 0.05, were two-sided, and with no adjustments for multiplicity. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata (version 14.1).

Results

A total of 1201 patients were selected to participate in the study, 291 (24%) from the USA and 910 (76%) from Europe (Table S1). A total of 410 rheumatologists participated in the study, 101 (25%) from the USA and 309 (75%) from Europe. Of these patients, 637 had sufficient information for us to be able to assess current active skin disease and were included in the joint-only involvement vs. joint and active skin involvement analyses (Table 1). Patients were not included if the reported skin and joint statuses were unknown. A total of 515 (81%) patients were reported to possess joint and active skin involvement in PsA. Joint-only involvement in PsA was reported for 122 (19%) patients. Patient demographics and characteristics are provided for the population when stratified according to joint and active skin symptom involvement in Table 1 and for the total population in Tables S1 and S2. The majority of patients had no prior diagnosis of comorbidities, but the percentage of patients with no comorbidities was significantly higher in the group of patients with joint-only involvement in PsA [77% (joint only) vs. 57% (joint + skin); p < 0.0001; Table 1]. In addition, patients with joint and active skin symptom involvement had numerically higher percentages in the majority of comorbidity categories (Table 1). Significant differences between the sub groups were observed in the comorbidity categories including anxiety, depression, hypertension, and no comorbidities. Additionally, it should be noted that some significant differences in comorbidities were observed between patients that were included in the skin and joint involvement analyses and those that were not included because of inadequate documentation (Table S2). These differences included anxiety [13% (included) vs. 5.1% (not included); p < 0.0001], atopic dermatitis [2.4% (included) vs. 0.71% (not included); p = 0.03], depression [12% (included) vs. 5.3% (not included); p = 0.0001], hypertension [22% (included) vs. 16% (not included); p = 0.003], and patients reporting no comorbidities [61% (included) vs. 70% (not included); p = 0.0007].

Physician-reported PsA-associated manifestations were investigated (Table 2). Patients with joint and active skin symptom involvement exhibited higher percentages of physician-reported associated manifestations in the majority of categories including stiffness in the morning [43% (joint only) vs. 60% (joint + skin); p = 0.001], fatigue/exhaustion [20% (joint only) vs. 40% (joint + skin); p < 0.0001], and pain on movement [26% (joint only) vs. 38% (joint + skin); p = 0.02] relative to patients with joint-only involvement. All physician-reported PsA-associated manifestations identified as being significantly higher were also found to be significant when we controlled for the number of joints affected by the disease.

General characteristics of PsA were also investigated. A similar number of joints were affected in patients, regardless of active skin involvement [3.4 ± 2.4 (joint only) vs. 3.7 ± 2.2 (joint + skin); p = 0.2; Fig. 1a]. Compared to patients with joint involvement only, patients with joint and active skin symptom involvement had significantly higher mean current levels of pain [2.8 ± 1.8 (joint only) vs. 3.6 ± 1.8 (joint + skin); p < 0.0001; Fig. 1b], and number of current PsA symptoms [0.9 ± 1.0 (joint only) vs. 2.4 ± 1.6 (joint + skin); p < 0.0001; Fig. 1c]. The overall number of other current symptoms (e.g., pain and stiffness-related joint symptoms, fatigue, nocturnal wakening, loss of grip, psychological disorders/thoughts, etc.) was significantly higher in patients with joint and active skin symptom involvement [1.5 ± 1.7 (joint only) vs. 2.7 ± 2.3 (joint + skin); p < 0.0001; Fig. 1d]. The percentage of patients who exhibited any flares in the past 12 months was significantly higher in PsA patients with joint and active skin symptom involvement [19% (joint only, nincluded = 119, nmissing = 3) vs. 39% (joint + skin, nincluded = 477, nmissing = 38); p < 0.0001] and the percentage of patients currently reported in remission was significantly lower in patients with joint and active skin symptom involvement in PsA [60% (joint only, n = 122) vs. 34% (joint + skin, n = 515); p < 0.0001]. When we controlled for number of joints affected, current levels of pain, current number of PsA symptoms, and the current number of other symptoms were all found to be significantly impacted by physician-perceived current skin severity (all p < 0.0001).

Profile of psoriatic arthritis disease in patients when stratified according to joint involvement without active skin symptoms (joint only, n = 122) and joint involvement with active skin symptoms (skin and joint, n = 515) measured by a number of affected joints, b current level of pain, c number of psoriatic arthritis symptoms, d number of other current symptoms. *p < 0.0001, p values from Student’s t test. SD standard deviation

In addition, we investigated correlations between some general characteristics of PsA and PsO skin severity, as determined by physician perception of current PsO skin severity. Both PASI (Fig. S1A) and BSA (Fig. S1B) results are positively correlated with physician-perceived skin severity (both p < 0.0001). Interestingly, physician-perceived skin severity was positively correlated with the total number of joints affected (p = 0.003; Fig. 2a), current level of pain (p < 0.0001; Fig. 2b), current number of PsA symptoms (p < 0.0001; Fig. 2c), and the current number of other symptoms (p < 0.0001; Fig. 2d). When regression analyses were performed to control for the number of affected joints, significant relationships were observed between skin severity and current levels of pain, current number of PsA symptoms, and the current number of other symptoms (all p < 0.0001).

Profile of psoriatic arthritis disease in patients according to physician classification of current skin severity [none (n = 170), mild (n = 538), moderate (n = 340), severe (n = 55)] as measured by a total number of affected joints, b current level of pain, c number of psoriatic arthritis symptoms, and the d number of other current symptoms. *p < 0.01, **p < 0.0001 both calculated from Spearman’s correlation. SD standard deviation

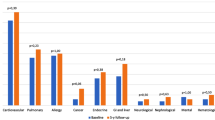

PsA disease state, HRQoL, and physical function were investigated in patients when stratified according to joint and active skin symptom involvement. PsA disease state was investigated using PtGA and PGA. PtGA was significantly lower (worse disease state) in patients with joint and active skin symptom involvement relative to patients with joint-only involvement in PsA [74 ± 23 (joint only) vs. 67 ± 21 (joint + skin); p = 0.03; Fig. 3a]. When PGA was used to investigate PsA disease status, no significant difference was observed between patients with joint symptoms alone and patients with joint and active skin involvement [66 ± 30 (joint only) vs. 63 ± 23 (joint + skin); p = 0.2; Fig. 3b]. HRQoL was investigated using the EQ-5D index, but no significant difference was observed between patients with joint and active skin involvement relative to patients with joint-only involvement in PsA [0.81 ± 0.25 (joint only) vs. 0.75 ± 0.24 (joint + skin); p = 0.1; Fig. 3c]. Physical function was investigated using HAQ-DI, but no significant difference was observed between patients with joint and active skin involvement relative to patients with joint-only involvement in PsA [0.50 ± 0.62 (joint only) vs. 0.68 ± 0.72 (joint + skin); p = 0.09; Fig. 3d]. When we controlled for number of joints affected, the differences observed for PtGA (p = 0.27), PGA (p = 0.08), EQ-5D (p = 0.46), and HAQ-DI (p = 0.54) were not significant.

Disease state, health-related quality of life, and physical function as measured by a patient global assessment, b physician global assessment, c EuroQoL (EQ)-5D, and d health assessment questionnaire disability index (HAQ-DI) in PsA patients when stratified according to joint involvement without active skin symptoms (joint only) and joint involvement with active skin symptoms (skin and joint). Some measures were missing for some patients; in these instances, the numbers of missing patients and included patients are displayed in the figure. *p < 0.05 vs. joint-only subgroup. p values from Student’s t test. n number of patients, SD standard deviation

Healthcare resource utilization was also investigated (Table 3). PsA patients with joint and active skin symptom involvement had a significantly higher number of healthcare professional consultations in the last year compared to patients with joint-only involvement [6.0 ± 4.1 (joint only) vs. 8.0 ± 4.6 (joint + skin); p < 0.0001]. A significantly higher percentage of patients with joint-only involvement in PsA had undergone a hospital procedure in the last 12 months [4% (joint only) vs. 2% (joint + skin); p = 0.02]. Patients had similar numbers of tests/assessments conducted regardless of joint and active skin symptom involvement [11 ± 5.9 (joint only) vs. 12 ± 6.0 (joint + skin); p = 0.6]. Patients with joint and active skin symptom involvement received a higher total number of treatments currently [1.8 ± 1.0 (joint only) vs. 2.1 ± 1.1 (joint + skin); p = 0.003], higher number of non-advanced therapies [1.2 ± 1.0 (joint only) vs. 1.5 ± 1.1 (joint + skin), p = 0.002], however similar percentages of patients were receiving advanced therapy (62% vs. 61%, p = 0.9). Furthermore, patients with joint and active skin involvement had a significantly higher number of concomitant conditions present [0.7 ± 1.1 (joint only) vs. 1.1 ± 1.3 (joint + skin), p = 0.0005]. When we controlled for the number of joints affected, only the number of healthcare professional consultations (p < 0.0001), total number of treatments currently being received (p = 0.0166), number non-advanced therapies (p = 0.0083), number of concomitant conditions present (p < 0.0001), and the number of patients who had not undergone a hospital procedure nor were a candidate for a hospital procedure (p = 0.0252) were observed to be significantly impacted by skin symptom involvement.

Discussion

We investigated the clinical presentation of joint and active skin symptom involvement and the associated impact on PGA, patient-reported outcomes (PtGA, HRQoL, and physical function), and healthcare resource burden in PsA. We observed that the majority of patients (81%) had both joint and active skin symptom involvement. Patients with joint and active skin symptom involvement had an overall worse clinical state including a higher level of pain, a greater number of concomitant conditions, and a higher number of PsA symptoms overall, with a greater percentage of patients experiencing morning stiffness, pain on movement, and fatigue compared to patients with joint-only symptoms. When skin severity was investigated, positive correlations were observed between skin severity and the number of joints affected, level of pain, number of PsA symptoms, and the number of other symptoms and these relationships between skin and pain, PsA symptoms, and other symptoms remained significant when we controlled for the number of affected joints.

The involvement of both joint and active skin symptoms in PsA was associated with significantly reduced PtGA scores but not lower PGA scores compared to patients with joint-only symptoms, although we note that the observed difference for PtGA is not independent of joints as based upon PSM analyses. Variability between patient- and physician-reported assessments has been reported by others and it may be due to psychological components of PsA [19]. The PtGA may be more sensitive to active skin symptom involvement due to the reported psychological and social impacts of skin involvement in PsA as reported by Salaffi and colleagues [19], and as reflected by Kavanaugh and colleagues [20] finding that improvements in the SF-36 mental component summary (MCS) were most pronounced in PsA patients treated with golimumab that achieved both ACR20 and PASI75. SF-36 was not included in this study, but PtGA results indicated worse health status in patients with joint and active skin symptom involvement in PsA. Thus, patient-reported outcomes indicate that the overall disease state and perhaps the quality of life are reduced to a greater degree when PsA involves both joint and active skin symptoms.

Patients with both joint and active skin involvement in PsA had a greater impact on the healthcare system with a statistically significant higher number of visits to any healthcare professionals in the last 12 months, greater total number of treatments received, and a higher number of non-biologic therapies relative to patients with joint involvement and no active skin symptoms, and these relationships remained significant when we controlled for the number of affected joints. As such, the patient-reported outcomes and healthcare resource burden of disease were poorer and increased, respectively, in patients when joint and active skin symptom components were active.

The heterogeneity of PsA disease manifestations and symptom variability contribute to the disease burden of PsA, although the relative influence of articular vs. skin symptoms to the overall disease burden is not clearly understood. Data from clinical trials have demonstrated that maximum improvement in HRQoL is achieved in PsA patients when both a skin and joint symptom response are achieved. From the IMPACT2 study, Kavanaugh and colleagues [14] reported that after 14 weeks of infliximab therapy, patients who achieved both PASI75 and ACR20 responses, compared to only one or the other, reported the greatest improvements in the SF-36 physical and mental component summaries (PCS and MCS, respectively). Similarly, from the GO-REVEAL study, Kavanaugh and colleagues [20] reported that patients who received golimumab for 24 weeks and achieved an ACR20 and/or PASI75 response had the greatest improvements in SF-36 PCS and MCS. The authors reported that the SF-36 PCS improvements were related to joint improvement, whereas SF-36 MCS improvements were related to both skin and joint symptom improvement [20]. Lastly, in a post hoc analysis from the ADEPT trial, Mease and colleagues [13] demonstrated that after 24 weeks of adalimumab therapy in PsA patients, those who achieved joint remission (DAS28 < 2.6), but not skin remission (PASI ≤ 3), experienced worse physical and functional impairments, pain, QoL, fatigue, and physician-assessed outcomes than those who achieved both skin and joint remission. Thus, current literature from clinical trials does support improved patient outcomes and better quality of life when both skin and joint manifestations are treated.

This multinational, cross-sectional, non-interventional study of a real-world sample of PsA patients demonstrates the impact of joint and active skin symptom involvement in PsA on patient outcomes but it has some limitations due to the nature of the study design. Limitations of our study include a potential selection bias of study participants due to the minimum requirements for participation in the disease programme, reliance on accuracy of reporting by the study participants and physicians, including severity defined by physician judgment instead of objective measures, and inability to demonstrate cause/effect with certainty (related to cross-sectional design). As a result of the multinational design of this study, HCRU results are dependent upon their respective healthcare systems and, as such, may not generalize to other healthcare systems. In addition, physician selection criteria required a minimum experience level and minimum number of consulting PsA patients thereby potentially biasing the healthcare utilization results of the surveyed population. Nonetheless, despite these limitations, our results are supported by publications from other research studies investigating, at least in part, contributions of the skin and joint components of PsA to the overall disease state and health outcomes.

Conclusions

In this real-world, non-interventional study, patients with PsA involving both joint and active skin symptom disease involvement exhibited a more severe overall disease state, worse patient outcomes, and increased HCRU relative to patients with joint-only involvement. Increasing skin severity was associated with higher PsA disease impact. Rheumatologist and patient perceptions/assessment of their overall disease-status appear to be different which may be due to the psychological burden of skin involvement in disease [19]. Our results indicate that association exists between active skin symptom involvement in PsA and outcomes, indicating that treating skin involvement of PsA should be considered along with treating joint involvement. Patients with significant joint and active skin symptom involvement may benefit most if managed jointly by rheumatologists and dermatologists [21]. As such, modern guidelines and treatment recommendations for PsA should be developed in coordination with both rheumatologists and dermatologists to address both the musculoskeletal and skin components of the disease [22].

References

Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Papp KA, et al. Prevalence of rheumatologist-diagnosed psoriatic arthritis in patients with psoriasis in European/North American dermatology clinics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:729–35.

de Vlam K, Gottlieb AB, Mease PJ. Current concepts in psoriatic arthritis: pathogenesis and management. Acta Dermato-Venereol. 2014;94:627–34.

Boehncke WH, Schon MP. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2015;386(9997):983–94.

Boehncke WH. Psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: flip sides of the coin? Acta Dermato-Venereol. 2016;96(4):436–41.

Cohen MR, Reda DJ, Clegg DO. Baseline relationships between psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: analysis of 221 patients with active psoriatic arthritis. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Seronegative Spondyloarthropathies. J Rheumatol. 1999;26(8):1752–6.

Elkayam O, Ophir J, Yaron M, Caspi D. Psoriatic arthritis: interrelationships between skin and joint manifestations related to onset, course and distribution. Clin Rheumatol. 2000;19(4):301–5.

Sokoll KB, Helliwell PS. Comparison of disability and quality of life in rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2001;28(8):1842–6.

Jones SM, Armas JB, Cohen MG, Lovell CR, Evison G, McHugh NJ. Psoriatic arthritis: outcome of disease subsets and relationship of joint disease to nail and skin disease. Br J Rheumatol. 1994;33(9):834–9.

Gottlieb AB, Mease PJ, Mark Jackson J, et al. Clinical characteristics of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis in dermatologists’ offices. J Dermatol Treat. 2006;17(5):279–87.

Christophers E, Barker JN, Griffiths CE, et al. The risk of psoriatic arthritis remains constant following initial diagnosis of psoriasis among patients seen in European dermatology clinics. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24(5):548–54.

Rosen CF, Mussani F, Chandran V, Eder L, Thavaneswaran A, Gladman DD. Patients with psoriatic arthritis have worse quality of life than those with psoriasis alone. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2012;51:571–6.

Husted JA, Gladman DD, Farewell VT, Cook RJ. Health-related quality of life of patients with psoriatic arthritis: a comparison with patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45:151–8.

Mease PJ, Mittal M, Joshi A, Chen N, Anderson J, Bao Y. SAT0578 value of treating both skin and joint manifestations of psoriatic arthritis: post-hoc analysis of the Adept Clinical Trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74(S2):870.

Kavanaugh A, Antoni C, Krueger GG, et al. Infliximab improves health related quality of life and physical function in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:471–7.

Anderson P, Benford M, Harris N, Karavali M, Piercy J. Real-world physician and patient behaviour across countries: disease-specific programmes—a means to understand. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:3063–72.

Fredriksson T, Pettersson U. Severe psoriasis–oral therapy with a new retinoid. Dermatologica. 1978;157(4):238–44.

Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):337–43.

Bruce B, Fries JF. The health assessment questionnaire (HAQ). Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23(5 Suppl 39):S14–8.

Salaffi F, Carotti M, Gasparini S, Intorcia M, Grassi W. The health-related quality of life in rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, and psoriatic arthritis: a comparison with a selected sample of healthy people. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009;7:25.

Kavanaugh A, McInnes IB, Krueger GG, et al. Patient-reported outcomes and the association with clinical response in patients with active psoriatic arthritis treated with golimumab: findings through 2 years of a phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65:1666–73.

Boehncke WH, Anliker MD, Conrad C, et al. The dermatologists’ role in managing psoriatic arthritis: results of a Swiss Delphi exercise intended to improve collaboration with rheumatologists. Dermatology. 2015;230(1):75–81.

Gossec L, Smolen JS, Ramiro S, et al. European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations for the management of psoriatic arthritis with pharmacological therapies: 2015 update. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(3):499–510.

Acknowledgements

Funding

This study and article processing charges were funded by Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA). All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Medical writing support in the preparation of this manuscript provided by Brian S. Comer, Ph.D. of Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA). Support for this assistance was funded by Eli Lilly and Company.

Authorship

All name authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval to the version to be published.

Disclosures

Kurt De Vlam is a consultant for Eli Lilly and Company, UCB, Pfizer, AbbVie, Celgene, Novartis, J&J, Bristol Myers Squibb and a speaker for for Pfizer, Celgene, Novartis, J&J. Joseph F. Merola is a consultant for Biogen IDEC, AbbVie, Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis, Pfizer, Janssen, UCB, Samumed, Science 37, Celgene, Sanofi Regeneron, Merck, GSK, and a speaker for AbbVie. Julie Birt is a full-time employee and stockholder of Eli Lilly and Company. David Sandoval is a full-time employee and stockholder of Eli Lilly and Company. Steve Lobosco is a full-time employee of Adelphi Real World. Rachel Moon is a full-time employee of Adelphi Real World. Gary Milligan is a full-time employee of Adelphi Real World. Wolf-Henning Boehncke has received honoraria as an advisor or speaker on the occasion of company-sponsored symposia from the following companies: Abbvie, Almirall, Biogen, Celgene, Janssen, Leo, Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The study was conducted in accordance with national market research and privacy regulations (European Pharmaceutical Market Research Association, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act). Patients provided informed consent prior to participating in this study and did not provide any personal identifiable information. As such, formal consent to release information was not required for this study. As a result of the non-interventional nature of the data collection method used in this study, patients were not placed at risk because of participation in the study.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.6478187.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

de Vlam, K., Merola, J.F., Birt, J.A. et al. Skin Involvement in Psoriatic Arthritis Worsens Overall Disease Activity, Patient-Reported Outcomes, and Increases Healthcare Resource Utilization: An Observational, Cross-Sectional Study. Rheumatol Ther 5, 423–436 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-018-0120-8

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40744-018-0120-8