Abstract

Background and aims

Reduction of intestinal load of phosphorus is important for the prevention and treatment of chronic kidney disease (CKD)-mineral and bone disorder (MBD). However, this strategy is limited by patients’ poor adherence to dietary prescription and by the existence of hidden sources of phosphorus. In addition to food containing phosphate-based additives, it was recently claimed that medications may contribute to increase the load of phosphate (P), mainly present as an excipient. To identify medications containing P as an excipient, we performed a systematic screening of medications which could potentially be prescribed for chronic oral therapies in CKD patients.

Methods

We examined 311 active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and 3763 branded or generic medications, identified by the anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) international classification system.

Results

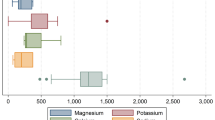

Sixty APIs (19.3 %) included at least one medication containing P as an excipient. In total, 472 medications (12.5 %) listed P as an excipient. The prevalence of medications containing phosphate as an excipient was highest for oral antidiabetic medications (23.8 %), followed by antidepressant (19.2 %), antihypertensive (17.5 %) and gastro-intestinal tract (16.4 %) medications. All other classes showed a prevalence <10 %. Within each ATC class, the APIs at risk of containing phosphate were identified as well as the prevalence of both branded and generic medications. Calcium hydrogen phosphate was the most prevalent form (77.7 %) of phosphate as an excipient.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that the prevalence of phosphate-containing medications is quite low and it is possible to identify, within each drug category, the medications containing P as an excipient. Calcium phosphate, the most prevalent form, has a lower rate of intestinal absorption than sodium phosphate salts. We did not measure the actual P content, but existing data (measured or estimated) show that it is generally low, except for a few medications that can be easily identified. Thus, the extra-phosphate load from medications may be of concern only in special cases, which could be further limited when correct information and prescriptions are given. The extra-phosphate load from P-containing food and beverages remains the main concern of hidden phosphorus sources in CKD patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Cupisti A, Kalantar-Zadeh K (2013) Management of natural and added dietary phosphorus burden in kidney disease. Seminar Nephrol 33:180–190

Galassi A, Cupisti A, Santoro A, Cozzolino M (2015) Phosphate balance in ESRD: diet, dialysis and binders against the low evident masked pool. J Nephrol 28:415–429

Moe SM, Zidehsarai MP, Chambers MA et al (2011) Vegetarian compared with meat dietary protein source and phosphorus homeostasis in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6:257–264

Karp H, Ekholm P, Kemi V, Hirvonen T, Lamberg-Allardt C (2012) Differences among total and in vitro digestible phosphorus content of meat and milk products. J Ren Nutr 22:344–349

Karp H, Ekholm P, Kemi V, Itkonen S, Hirvonen T, Närkki S, Lamberg-Allardt C (2012) Differences among total and in vitro digestible phosphorus content of plant foods and beverages. J Ren Nutr 22:416–422

Sullivan C, Sayre SS, Leon JB et al (2009) Effect of food additives on hyperphosphatemia among patients with end-stage renal disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 301:629–635

Sherman RA, Ravella S, Kapoian T (2015) A dearth of data: the problem of phosphorus in prescription medications. Kidney Int 87:1097–1099

Sultana J, Musazzi UM, Ingrasciotta Y et al (2015) Medication in an additional source of phosphate in chronic kidney disease patients. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 25:959–967

Wendt P, Rodehutscord M (2004) Investigations on the availability of inorganic phosphate from different sources with growing White Pekin ducks. Poult Sci 83:1572–1579

León JB, Sullivan CM, Sehgal AR (2013) The prevalence of phosphorus-containing food additives in top-selling foods in grocery stores. J Ren Nutr 23:265–270

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cupisti, A., Moriconi, D., D’Alessandro, C. et al. The extra-phosphate intestinal load from medications: is it a real concern?. J Nephrol 29, 857–862 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-016-0306-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40620-016-0306-5