Abstract

Background

The aim of this paper was to explore disparities associated with the route of hysterectomy in the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) health system and to evaluate whether the hysterectomy clinical pathway implementation impacted disparities in the utilization of minimally invasive hysterectomy (MIH).

Methods

We performed a retrospective medical record review of all the patients who have undergone hysterectomy for benign indications at UPMC-affiliated hospitals between fiscal years (FY) 2012 and 2014.

Results

A total number of 6373 hysterectomy patient cases were included in this study: 88.7% (5653) were European American (EA), 11.02% (702) were African American (AA), and the remaining 0.28% (18) were of other ethnicities. We found that non-EA, women aged 45–60, traditional Medicaid, and traditional Medicare enrollees were more likely to have a total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH). Residence in higher median income zip code (> $61,000) was associated with 60% lower odds of undergoing TAH. Both FY 2013 and 2014 were associated with significantly lower odds of TAH. Logistic regression results from the model for non-EA patients for FY 2012 and FY 2014 demonstrated that FY and zip code income group were not significant predictors of surgery type in this subgroup. Pathway implementation did not reduce racial disparity in MIH utilization.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that there is a significant disparity in MIH utilization, where non-EA and Medicaid/Medicare recipients had higher odds of undergoing TAH. Further research is needed to investigate how care standardization may alleviate healthcare disparities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Racial and ethnic minorities often receive inferior healthcare quality compared to non-minorities, even after adjusting for access-related factors, such as income and insurance status [1]. A similar situation is oftentimes the case for individuals from lower socioeconomic status [2]. According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), quality healthcare is “doing the right thing, at the right time, in the right way, for the right person, and having the best possible results” [3]. Various factors contribute to the existing healthcare disparities, such as the health systems’ policies, the healthcare professionals’ attitudes and biases, and the patients’ knowledge on how to access healthcare and their ability to actively take part in the clinical decision-making process [1, 4]. The Institute of Medicine defines healthcare disparity as “racial or ethnic differences in the quality of healthcare that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, preferences, and appropriateness of intervention” [1].

Previously published research documented healthcare disparities in many healthcare areas [5,6,7,8,9]. These healthcare disparities span a broad range of conditions and interventions, from routine influenza vaccinations [10] to critical cardiac revascularization surgeries [11]. The obstetrics and gynecology field is no exception to healthcare disparities, where significant healthcare disparities exist among women of various ethnicities when it comes to prenatal care, access to minimally invasive surgery, etc. [12,13,14,15]. Previous publication demonstrated that for endometrial cancer care, insurance type and race were important predictors of the use of robotic surgery with European American (EA) women from high socioeconomic status being more likely to get the robotic surgery [16].

Benign gynecologic conditions, such as prolapse, heavy bleeding, pelvic pain, fibroids, endometriosis, and others, affect a large percentage of women as they age. There are many factors that may be associated with the onset of benign gynecologic conditions. Some of these factors include age, heredity, hormonal factors, and obesity [17]. A recent systematic review suggested that uterine fibroids occur in 70% of women [18]. The Women’s Health Initiative Hormone Replacement Therapy Clinical Trial suggested a 14% prevalence of uterine prolapse among the research participants [19]. Africian American (AA) women may bear a greater burden of disease than their EA counterparts and oftentimes experience disparities due to access to care [20]. In particular, AA women present with larger, more numerous, and more rapidly growing fibroids than EA women [15]. AA women are more likely to report severe pelvic pain [21] and are two times as likely to have complications from surgery for fibroids [22]. As suggested by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines and our previously published paper, one of the best practices to treat these conditions in women who are not good candidates for pharmacological management is same-day minimally invasive surgery, which decreases the rate of complications [23, 24]. In 2012, the UPMC Health System introduced a computer-based evidence-based hysterectomy decision-making algorithm for benign gynecologic indications with the aim of reducing abdominal hysterectomy rates, improving patient outcomes, and decreasing costs [23, 25, 26] that physicians need to follow before making treatment decisions. Within 3 months of the pathway introduction, UPMC hospitals implementing the pathway were complete, with the exception of a few hospitals which were intentionally delayed. The aim of this study was to explore disparities associated with the route of hysterectomy utilization in the UPMC system and to evaluate whether the clinical pathway impacted disparities in minimally invasive hysterectomy (MIH) utilization.

Methods

We performed a retrospective medical record review of all patients who have undergone hysterectomy for benign indications at the UPMC-affiliated hospitals between fiscal years (FY) 2012 and 2014. A total number of 6569 hysterectomies for non-cancerous indications were performed across 14 UPMC Health System-affiliated hospitals between FY 2012 and FY 2014. This study was considered exempt by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board (no human subject involvement, Internal Review Board #PRO15030115). Study data were gathered from the following sources within the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center system: (1) Medipac (HBO Corporation, Atlanta, Georgia); (2) EpicCare (Epic Systems, Verona, Wisconsin); (3) Crimson (The Advisory Board Company, Austin,Texas); and (4) Cerner (Cerner Corporation, Kansas City, Missouri). Using the International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision codes, eligible cases were identified, and hysterectomy routes were documented.

We collected information regarding patients’ age, race/ethnicity (EA, AA, and others including Hispanic/Latino, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Native American), insurance status (commercial, traditional Medicaid, managed Medicaid, traditional Medicare, managed Medicare, and others), residential zip code, and type of hysterectomy (total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH), laparoscopic, vaginal, and robotic). Patients were categorized into three groups based on their age (< 45, 45–60, and > 60 years). They were also categorized based on their self-identified race/ethnicity, into EA and non-EA (including AA and other races) groups. We used residential zip codes as a proxy for annual median household income (based on 2010–2014 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates), by using the US Census Bureau, American FactFinder [27], and for residence place. After performing analysis by zip code, patients were classified into four groups based on the median annual household income in their zip code residential areas: ≥ $61,000, $46,000–$60,999, $37,000–$45,999, and <$37,000.

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the overall data distribution, and analysis of variance was used to compare the mean ages of the patients for each fiscal year. A Wald chi-square test in a stepwise logistic regression model was used to assess the independent association of sociodemographic variables with undergoing TAH compared to MIH for all 3 years jointly. To examine whether the pathway implementation was associated with a reduction in racial disparity, we checked for fiscal year by race interaction for FY 2012 and FY 2014. Two logistic regression models were used to assess the independent association of sociodemographic variables with undergoing TAH compared to MIH for FY 2012 and FY 2014 among EA and non-EA, separately. Data analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). All tests were two-sided, and significance level was set at α = 0.05.

Results

From FY 2012 to FY 2014, 6569 hysterectomies for non-cancerous indications were performed at the UPMC-affiliated hospitals. A total number of 196 cases had missing data and were excluded from the analyses. The mean age of all 6373 participants across the 3 years was 48.68 years (standard deviation 11.69). The mean age of participants by year was 48.9, 48.2, and 48.8 years for FY 2012, FY 2013, and FY 2014, respectively (P = .083). Overall, 88.7% (5653) were EA, 11.02% (702) were AA, and 0.28% (18) were of other ethnicities; 23.41% (1492) of hysterectomies were total abdominal, 44.41% (2830) laparoscopic, 13.18% (840) robotic, and 19% (1211) vaginal. Seventy percent (4478) of patients had commercial insurance, 10.56% had managed Medicaid, 9.37% had managed Medicare, and 10.0% had traditional Medicare, traditional Medicaid, or other insurances. In this population, 42.7% of participants were in the 45–60-year age group, 40.5% were < 45 years, and 16.8% were > 60 years. Of all the participants, 34% (2170) had an average zip code-associated annual household income of $46,000–$60,999, followed by 32.9% with $37,000–$45,999, while 13.8% had < $37,000, and 19.2% had > $61,000. Over 99% of the patients were English speakers. Table 1 shows the general characteristics of the study population by fiscal year and route of surgery.

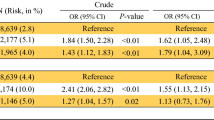

There were several factors that were associated with the odds of undergoing TAH compared to MIH in the multivariate model (Table 2). Women aged 45–60 had 50% higher odds of undergoing TAH compared to women < 45 years (P < .001). Compared to commercial health insurance, traditional Medicaid recipients had the highest odds (odds ratio [OR], 3.66; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.62–5.1; P < .001) of undergoing TAH, followed by “others” (OR, 2.0; 95% CI, 1.3–3.0; P < .001) and traditional Medicare (OR, 1.4; 95% CI, 1.1–1.9; P = .006). A significant interaction effect between race and median zip code income level was observed (P = .05). Among EA, those with median zip income level of $37,000–$45,999 had 31% higher odds of having TAH (OR, 1.3; 95% CI, 1.0–1.6; P = .015) as compared to a reference group of women residing in zip codes with the median income of under $37,000, while those with a median zip income level > $61,000 had 55% lower odds of undergoing TAH (OR, 0.45; 95% CI, 0.035–0.59; P < .001). Among non-EA, there was no significant difference in the odds of having TAH between different income levels. At each income level, non-EA had higher odds of undergoing TAH (ranging from 1.38 in the $37,000–$45,999 income bracket to 2.87 in the > $61,000 income bracket) compared to EA of the same zip code income level. Controlling for race, age, insurance type, income, and race-by-income interaction effect, FY 2013 was associated with lower odds of TAH (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.7–0.9; P = .007), while FY 2014 was associated with even lower odds of TAH (OR, 0.5; 95% CI, 0.4–0.6; P < .001) compared to FY 2012.

We added a fiscal year-by-race interaction term to the logistic regression model described above for FY 2012 and FY 2014 to see if disparity level changed between FY 2012 and FY 2014. Controlling for race, age, insurance type, income, and race-by-income interaction effect, a Wald chi-square test for the fiscal year-by-race interaction effect showed a non-significant result (P = .111).

The association between the odds of MIH and other factors differing by race was also tested. Although none of the interaction effects with race achieved statistical significance, we fit separate models by race. The results of the logistic regression model for non-EA patients for FY 2012 and FY 2014 showed that fiscal year and income groups were not significant predictors of the type of surgery. The final model only included insurance types and age groups (Table 3). Women aged 45–60 years had higher odds of having TAH compared to women < 45 years (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.1–2.4; P = .010). In non-EA patients, those with “traditional Medicaid” had more than five times higher odds of TAH (OR, 5.8; 95% CI, 1.8–18.7; P = .003) compared to those with “commercial” insurance. There was no significant difference between other insurance types compared to “commercial” (Table 3).

Lastly, the logistic regression results from the model run for EA patients for FY 2012 and FY 2014 (Table 4) demonstrated that EA women aged 45–60 years had higher odds of undergoing TAH compared to women < 45 years (OR, 1.6; 95% CI, 1.4–2.0; P < .001). The income group of > $61,000 had 0.6 lower odds of TAH, compared to the income group of < $37,000. Traditional Medicare, traditional Medicaid, and “other” insurances had two to four times higher odds of having TAH compared to the “commercial” insurance group. Overall, controlling for age group, insurance type, and annual household income, EA women had 0.47 times lower odds of undergoing TAH in FY 2014 compared to FY 2012.

Discussion

Consistent with previous studies [28, 29], this study demonstrated that age, income, insurance type, and race/ethnicity are independent factors that were associated with the odds of undergoing TAH. This study showed that after implementing the hysterectomy pathway, “fiscal year” becomes another predictor for TAH utilization, potentially suggesting that TAH has been decreasing after more physicians became exposed to pathway. The same factors mentioned above were associated with the odds of TAH in EA; however, only age and insurance group significantly contributed to the odds of TAH compared to MIH for non-EA. This study corroborated previous reports suggesting that the Medicare recipients may not always be getting the same care as carriers of other insurance types [30, 31]. This study identified an interesting finding where for EA women, a median income level of $37,000–$45,999 for the zip code of residence was associated with highest odds of having an opened procedure, as compared to lower or higher zip code income groups. This finding warrants further investigation.

The current study demonstrated that even after implementing the hysterectomy pathway, non-EA still received less MIH compared to EA. The ecosocial theory, developed by Nancy Krieger [32], may potentially explain this difference. The ecosocial theory seeks to explain the distribution of disease at the population level by focusing on the impact of the social and physical societal determinants of health. Economic and social deprivation among AA women may lead to more severe medical conditions that would necessitate TAH. While the nature of the data collected from the UPMC Health Plan does not allow us to determine the social, economic, and healthcare access problems encountered by these women, these issues will become the focus of our future research studies targeting patients directly. However, one cannot attribute the observed difference solely to social issues because it has been shown that there are some differences in the presentation of benign gynecologic conditions among AA women compared to EA women. Kjerulff et al. reported that the average weight of the uterus in AA women who underwent surgery for leiomyomas was 420.8 g compared to 319.1 g in EA women (P = .001), which was due to a larger-sized uterus and a greater number of tumors [21]. In a study conducted among 101 non-parous AA and EA women, aged 18–30, with no prior diagnoses of leiomyoma or clinical symptoms of the presence of a leiomyoma, it was reported that there was a significant difference in the average uterus volume (using transvaginal ultrasound), between AA and EA women (64.4 ± 62.3 vs. 41.1 ± 14.6 cm3; P = .007) [33]. Since our pathway has a limit of 10 cm for uterus size, it is plausible to assume that some of the non-EA women did not receive MIH simply because they were not suitable candidates for it. Thus, our future research will attempt to evaluate if hysterectomy indication has an impact on these disparities, which was not possible in the context of this study.

To better understand the reasons leading to this observation, we tried to take a systematic approach to the well-established reasons of healthcare disparity. The reasons for healthcare disparities can be classified into three levels: (1) healthcare system level, (2) care delivery level, and (3) patient level [5, 34]. At the healthcare level, issues such as complexity and fragmentation of the healthcare system and linguistic barriers for those with limited English proficiency are the main ones. Care delivery level includes stereotyping, personal bias, and prejudice by healthcare providers toward patients, and clinical uncertainty and difficulties in clinical decision-making. Last, but not least, are patients’ mistrust and attitude toward the system and healthcare provider.

A particular strength of our study is its broad geographical scope; 41% of the medical–surgical market share in western Pennsylvania (29 counties) were held by the UPMC Health System in FY 2015 [35]. Also, it is encouraging that lack of language skills was not a factor in MIH utilization, as over 99% of all patients assessed in this study were English speakers. Even if the system works properly and there are no language barriers, the patient still needs to build effective communication with the providers and vice versa. Studies have shown that minorities are less likely to develop a trusting rapport with healthcare providers [36, 37], which may lead to misunderstanding their physician and the treatment plan, fear of asking questions, and believing that their physician does not listen to them make it difficult for the physician and patient to make an informed decision [38]. These trust issues can range from questioning the competence and training of the provider; the provider is prescribing a procedure based solely on their race; and the procedure is being prescribed to make money. At the present time, the literature does not offer a clear explanation as to why AA women would exhibit increased trust issues. While the study did not examine patient/provider communication, it could be a potential reason for some of the observed disparity and needs to be investigated in future studies. Pathways may potentially become a powerful tool to minimize stereotyping and clinical uncertainty; however, more research about pathway utilization is needed in the fields of gynecology. Since miscommunication of healthcare providers and patients may affect utilization of MIH, further research in this area is also warranted.

One of the limitations of this study was that we did not have sufficient minorities other than the AA group to assess the effect of the hysterectomy pathway on groups like Asian American and Latina women. According to the US Census Bureau, as of July 1, 2014, EA constituted 77.4% and AA constituted 13.2% of the Allegheny County’s population [39], which limited our study to the investigation of these two groups. Also, this study’s database did not give us an opportunity to examine differences by surgeon, as it may be possible that results differed by surgeon characteristics such as surgical volume, physician training, and physician practice location. Our dataset did not allow us to obtain reliable information on patient BMIs and uterine size prior to surgery. These limitations will be addressed in the scope of our future research.

Additionally, we did not collect annual household income information and used residential zip codes as a proxy for annual household income, which has its inherent limitations. The 3-year period might not be long enough to examine this hypothesis; therefore, we would like to re-examine the overall effect of the hysterectomy clinical pathway in a longer time frame in future investigations.

The strength of this study is the wide catchment area, the high number of physicians and facilities utilizing the hysterectomy clinical pathway, and the large sample size with well-balanced procedure types. A centralized data management system made it easy to access reliable and uniform data.

Although this study did not fully support our hypothesis that implementing a clinical pathway impacts racial disparities, we believe that pathway implementation can be an effective tool for improving quality and value of care and should be further investigated by both quantitative and qualitative scientists to assess its effectiveness. More large-scale studies are also needed in the area of patient provider communications because of its potential impact on healthcare disparities.

References

Nelson AR, Smedley BD. Stith AY. Unequal treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. National Academies Press; 2002.

Adler NE, Newman K. Socioeconomic disparities in health: pathways and policies. Health Aff. 2002;21:60–76.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Your guide to choosing quality health care: a quick look at quality. 2016. http://archive.ahrq.gov/consumer/qnt/. Accessed May 1 2017.

Carter-Pokras O, Baquet C. What is a “health disparity”? Public Health Rep. 2002;117:426.

Nelson AR, Smedley BD, Stith AY, Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care (full printed version). National Academies Press; 2002.

Ahmed AT, Welch BT, Brinjikji W, Farah WH, Henrichsen TL, Murad MH, et al. Racial disparities in screening mammography in the United States: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14:157–65. e9

Doshi RP, Aseltine RH Jr, Sabina AB, Graham GN. Racial and ethnic disparities in preventable hospitalizations for chronic disease: prevalence and risk factors. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;

Musselwhite LW, Oliveira CM, Kwaramba T, de Paula PN, Smith JS, Fregnani JH, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in cervical cancer screening and outcomes. Acta Cytol. 2016;60:518–26.

Haider AH, Scott VK, Rehman KA, Velopulos C, Bentley JM, Cornwell EE 3rd, et al. Racial disparities in surgical care and outcomes in the United States: a comprehensive review of patient, provider, and systemic factors. J Am Coll Surg. 2013;216:482–92. e12

Schneider EC, Cleary PD, Zaslavsky AM, Epstein AM. Racial disparity in influenza vaccination: does managed care narrow the gap between african americans and whites? JAMA. 2001;286:1455–60.

Epstein AM, Weissman JS, Schneider EC, Gatsonis C, Leape LL, Piana RN. Race and gender disparities in rates of cardiac revascularization: do they reflect appropriate use of procedures or problems in quality of care? Med Care. 2003;41:1240–55.

Bryant AS, Worjoloh A, Caughey AB, Washington AE. Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: prevalence and determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:335–43.

Healy AJ, Malone FD, Sullivan LM, Porter TF, Luthy DA, Comstock CH, et al. Early access to prenatal care: implications for racial disparity in perinatal mortality. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:625–31.

Lee J, Jennings K, Borahay MA, Rodriguez AM, Kilic GS, Snyder RR, et al. Trends in the national distribution of laparoscopic hysterectomies from 2003 to 2010. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2014;21:656–61.

Jacoby VL, Fujimoto VY, Giudice LC, Kuppermann M, Washington AE. Racial and ethnic disparities in benign gynecologic conditions and associated surgeries. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202:514–21.

Chan JK, Gardner AB, Taylor K, Blansit K, Thompson CA, Brooks R, et al. The centralization of robotic surgery in high-volume centers for endometrial cancer patients—a study of 6560 cases in the US. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;138:128–32.

Mayo Clinic. Uterine fibroids. 2017. http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/uterine-fibroids/symptoms-causes/dxc-20212514. Accessed July 6 2017.

Stewart EA, Cookson CL, Gandolfo RA, Schulze-Rath R, Epidemiology of uterine fibroids: a systematic review. BJOG. 2017; doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14640.

Hendrix SL, Clark A, Nygaard I, Aragaki A, Barnabei V, McTiernan A. Pelvic organ prolapse in the Women's Health Initiative: gravity and gravidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:1160–6.

Politzer RM, Yoon J, Shi L, Hughes RG, Regan J, Gaston MH. Inequality in America: the contribution of health centers in reducing and eliminating disparities in access to care. Med Care Res Rev. 2001;58:234–48.

Kjerulff KH, Langenberg P, Seidman JD, Stolley PD, Guzinski GM. Uterine leiomyomas. Racial differences in severity, symptoms and age at diagnosis. J Reprod Med. 1996;41:483–90.

Roth TM, Gustilo-Ashby T, Barber MD, Myers ER. Effects of race and clinical factors on short-term outcomes of abdominal myomectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:881–4.

Linkov F, Sanei-Moghaddam A, Edwards RP, Lounder PJ, Ismail N, Goughnour SL, et al. Implementation of hysterectomy pathway: impact on complications. Womens Health Issues. 2017; doi:10.1016/j.whi.2017.02.004.

ACOG. Chosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. 2017. https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Gynecologic-Practice/Choosing-the-Route-of-Hysterectomy-for-Benign-Disease. Accessed July 10 2017.

Sanei-Moghaddam A, Ma T, Goughnour SL, Edwards RP, Lounder PJ, Ismail N, et al. Changes in hysterectomy trends after the implementation of a clinical pathway. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:139–47.

Mansuria SM, Comerci J, Edwards R, Sanei Moghaddam A, Ma T, Linkov F. Changes in hysterectomy trends and patient outcomes following the implementation of a clinical pathway [7]. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127(Suppl 1):3s.

Venkitaraman AR. Cancer suppression by the chromosome custodians, BRCA1 and BRCA2. Science. 2014;343:1470–5.

Jacoby VL, Autry A, Jacobson G, Domush R, Nakagawa S, Jacoby A. Nationwide use of laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with abdominal and vaginal approaches. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:1041–8.

Abenhaim HA, Azziz R, Hu J, Bartolucci A, Tulandi T. Socioeconomic and racial predictors of undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy for selected benign diseases: analysis of 341487 hysterectomies. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:11–5.

Spencer CS, Gaskin DJ, Roberts ET. The quality of care delivered to patients within the same hospital varies by insurance type. Health Aff. 2013;32:1731–9.

Hasan O, Orav EJ, Hicks LS. Insurance status and hospital care for myocardial infarction, stroke, and pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2010;5:452–9.

Krieger N. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30:668–77.

Marsh EE, Ekpo GE, Cardozo ER, Brocks M, Dune T, Cohen LS. Racial differences in fibroid prevalence and ultrasound findings in asymptomatic young women (18–30 years old): a pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2013;99:1951–7.

Betancourt J, Green A, King R, Tan-McGrory A, Cervantes M, Renfrew M. Improving quality and achieving equity: a guide for hospital leaders. Boston: Disparities Solutions Center and Institute for Health Policy, Massachusetts General Hospital; 2008.

UPMC. By the numbers: UPMC facts and figures. 2015. http://www.upmc.com/ABOUT/FACTS/NUMBERS/Pages/default.aspx. Accessed May 1 2017.

Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:2084–90.

Gordon HS, Street RL, Sharf BF, Kelly PA, Souchek J. Racial differences in trust and lung cancer patients' perceptions of physician communication. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:904–9.

Collins KS,Fund C, Diverse communities, common concerns: assessing health care quality for minority Americans. Commonwealth Fund New York; 2002.

U.S. Census Bureau. nnFacts. 2015. http://www.census.gov/quickfacts/table/PST045215/00. Accessed May 1 2017.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the “Bench at the Bedside” program of the Beckwith Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Suketu Mansuria declares speakers bureau surgeon educator with Covidien/Medtronic. All other authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. For this type of study, formal consent is not required.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was not required for this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sanei-Moghaddam, A., Kang, C., Edwards, R.P. et al. Racial and Socioeconomic Disparities in Hysterectomy Route for Benign Conditions. J. Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 5, 758–765 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0420-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-017-0420-7