Abstract

Purpose of Review

Cryptosporidium spp. (C. hominis and C. parvum) are a major cause of diarrhea-associated morbidity and mortality in young children globally. While C. hominis only infects humans, C. parvum is a zoonotic parasite that can be transmitted from infected animals to humans. There are no treatment or control measures to fully treat cryptosporidiosis or prevent the infection in humans and animals. Our knowledge on the molecular mechanisms of Cryptosporidium-host interactions and the underlying factors that govern infectivity and disease pathogenesis is very limited.

Recent Findings

Recent development of genetics and new animal models of infection, along with progress in cell culture platforms to complete the parasite lifecycle in vitro, is greatly advancing the Cryptosporidium field.

Summary

In this review, we will discuss our current knowledge of host-parasite interactions and how genetic manipulation of Cryptosporidium and promising infection models are opening the doors towards an improved understanding of parasite biology and disease pathogenesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The protozoan parasite Cryptosporidium spp. (C. hominis and C. parvum) is recognized as a leading cause of diarrhea and mortality in young children and immunocompromised individuals globally [1,2,3]. Repeated episodes of cryptosporidiosis in children living in resource-poor settings have been associated with malnutrition and growth defects [1, 4, 5]. While C. hominis infects only humans, C. parvum is a zoonotic pathogen and can infect both humans and animals [6]. Cryptosporidium parvum is an important veterinary parasite and a major cause of diarrheal disease in ruminant livestock, especially neonatal calves [7,8,9]. Transmission of Cryptosporidium infection occurs via the fecal-oral route upon ingestion of oocysts from contaminated food or water or via animal contact. These thick-walled infectious oocysts are resistant to routine disinfection procedures such as chlorination, thus making them difficult to eliminate from swimming pools, animal housing facilities, and the environment [8, 10]. Due to their resilience to disinfection and highly infectious nature of oocysts, large outbreaks have occurred as a result of contamination of drinking water supply, and frequent outbreaks associated with treated recreational water facilities are reported from developed countries [11,12,13].

There are no drugs to effectively treat cryptosporidiosis and no vaccine to prevent the infection in young children, HIV/AIDS patients, and animals [14,15,16]. The only available and FDA approved drug, nitazoxanide, has limited efficacy in children and is not effective in immunocompromised individuals [17, 18]. Thus, it is critical to gain an in-depth understanding of Cryptosporidium biology and host-parasite interactions in order to develop effective drugs and vaccines to curb cryptosporidiosis. There have been several recent major technological advances in the field of Cryptosporidium that is rapidly expanding our fundamental knowledge on parasite lifecycle and disease pathogenesis. These include the development of molecular genetics to manipulate the parasite genome using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat/ CRISPR associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) system that has unveiled new aspects of parasite biology and validation of drug targets, promising in vitro models for parasite propagation and new animal infection models to study host-parasite interactions [19••, 20••, 21••, 22••, 23••, 24•, 25, 26, 27•].

The simple life cycle of Cryptosporidium

The lifecycle of Cryptosporidium is simple since both the asexual and sexual stages are completed within a single host, and the target of infection is the intestinal epithelial cell in the case of C. parvum [28, 29]. This is in contrast to related apicomplexan parasites such as Toxoplasma gondii and Plasmodium falciparum that have a complex life cycle which requires separate hosts to complete asexual and sexual development, and also these parasites are capable of infecting multiple cell types.

Interestingly, Cryptosporidium has a unique blend of features that it has adapted from Plasmodium and Toxoplasma as well as from gut-infecting gregarine apicomplexan parasites of invertebrates during evolution [30,31,32,33]. Although there are differences in terms of host cell specificity and lifecycle completion, Cryptosporidium has conserved features that are typical of apicomplexans such as apical secretory organelles (rhoptry, micronemes, and dense granules) for parasite invasion, as well as similar replicating and cyst stages. However, it lacks many components of the moving junction machinery that allows active invasion of Toxoplasma and Plasmodium and has also lost its apicoplast and mitochondrion and is dependent on glycolysis for its energy requirements [34, 35]. The absence of some conserved invasion components is not surprising, since Cryptosporidium does not become totally intracellular after invasion, but displays this peculiar epicellular localization upon encapsulation by the host cell membrane [31, 32]. The molecular mechanisms from both the host and parasite side that lead to this epicellular niche are not known.

The Cryptosporidium lifecycle begins with the oral ingestion of infective form, the thick-walled oocysts, and each oocyst contains four sporozoites [36]. These oocysts undergo excystation due to change in temperature, pH, action of bile salts, and parasite proteases, along with other unknown triggering factors. The released sporozoites glide and invade intestinal epithelial cells (enterocytes) and transform into a uninucleated trophozoite. Trophozoites undergo three rounds of asexual replication (merogony) to produce a mature type I meront with eight merozoites. Merozoites released from the type I meront invade adjacent intestinal epithelial cells to yield additional type I meronts or transform into type II meronts that contain four merozoites. Merozoites from type II meronts are thought to transform into the sexual stages, the macrogamont (female) and microgamont (male). The macrogamont has a large, eccentric nucleus and in its cytoplasm stores amylopectin granules, lipid vacuoles, and wall forming bodies. The microgamont gives rise to 16 non-flagellated, bullet-shaped male gametes that find female gametes by unknown mechanisms, resulting in fertilization [36, 37]. The fusion of the male and female nuclei results in the formation of a diploid zygote that undergoes meiosis and sporogony to form four haploid sporozoites within an oocyst. This sporulated oocyst is then passed in the feces to be taken up by another host for the cycle to continue.

Each sequential step in the Cryptosporidium developmental cycle has to be precisely programmed for the successful completion of its lifecycle. This highly regulated programming has been demonstrated by time course infection experiments and immunofluorescence microscopy in cell culture by infecting human ileocecal adenocarcinoma cells (HCT-8) with genetically engineered C. parvum strains and also by using a combination of 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU) labeling and monoclonal antibodies against different parasite stages [37,38,39,40]. Asexual stages have been reported to be predominant up to 36 h of infection, and after that, there is a dramatic shift towards development of sexual stages. At 36 h post infection, microgamonts begin to emerge, followed by macrogamonts and these stages are abundant at 48 h of infection [37, 39]. Although we now recognize that parasite development is timed and all steps occur in a coordinated manner, we still do not know the signals that the parasite senses and the regulatory mechanisms that control progression from one stage to another. Transcriptomics studies have revealed a stage-specific expression of Cryptosporidium genes during the parasite developmental stages. There are clearly different gene expression profiles at asexual stage versus female gametocytes; and genes required for genetic recombination, amylopectin, trehalose metabolism and oocyst wall formation have been reported to be highly upregulated in the female gametocytes [37, 41]. Recent studies have also reported the emerging role of long non-coding RNAs (lncRNA) delivered by Cryptosporidium into the host cell to manipulate host gene expression and pathogenesis [42,43,44,45].

The requirement of Cryptosporidium to complete the entire lifecycle in a single host has been challenging to mimic in the laboratory for continuous culture of the parasite. The commonly used HCT-8 cells only allow a short window of 72 h to maintain C. parvum growth, and the culture arrests at this point with no new oocyst formation. Using the power of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, reporter strains were generated to track Cryptosporidium development in HCT-8 cells and in IFN-gamma knockout (IFN-γ KO) mice [37]. After 48 h of infection, sexual stages of the parasite were reported to predominate in culture, but fertilization of male and female gametes did not occur. This block in fertilization could be overcome in infected IFN-γ KO mice, where productive fertilization of gametes resulted in oocyst formation [37]. There have been increasing efforts in recent years for the development of in vitro systems that can allow completion of the entire lifecycle of the parasite in the laboratory and sustain long-term growth for viable oocyst production [24•]. These include three-dimensional bioengineered system utilizing immortalized cancerous Caco-2 and HT29-MTX cells, human intestinal enteroids (HIE) derived from intestinal tissues, human small intestine and lung organoids, and stem-cell derived cultures of mouse intestinal epithelial cells under air-liquid interface (ALI) conditions [21••, 23••, 46, 47]. In the ALI culture system, transgenic fluorescent parasite lines were generated using CRISPR/Cas9 editing and used to demonstrate genetic crossing in vitro [21••]. Furthermore, the long-term growth of C. parvum in ALI culture system has been employed to test anti-cryptosporidial compounds for time-dependent killing of the parasite in order to define cidal versus static activity of these compounds [39].

Cryptosporidium—host cell interactions

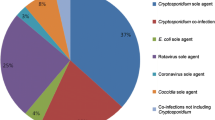

The interaction of Cryptosporidium with its host is complex; and an interplay of several parasite and host factors determines disease pathogenesis or protection from infection (Fig. 1). Therefore, it is critical to understand these interactions in order to identify key biological mechanisms that can be targeted for the future development of effective vaccines and drugs against cryptosporidiosis. However, our current knowledge on parasite attachment, invasion, replication, and gametocyte development is very limited.

On the parasite side, there are only a handful of factors that have been identified until date to play a role in host-parasite interactions [29, 48]. These include the thrombospondin related adhesive protein (TRAP-C1), circumsporozoite-like protein (CSL), P23, CP47, Cpa135, CPS-500, mucins (CpMuc4, CpMuc5) and mucin-like glycoproteins GP900, GP60 (proteolytically cleaved into GP40/15 mature glycopeptides), and C-type lectin (CpClec) [29, 48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57]. These proteins have been reported to localize to the apical end or on the surface of sporozoite, and many of these are shed in trails during gliding motility of sporozoites. Thus, based on their localization, binding to host cell or antibody-based inhibition of infection, these proteins have been implicated to play a role in the initial attachment and invasion process [48, 51, 58]. We still do not fully understand the gamut of parasite secreted proteins that interact with the host for a productive zoite attachment and invasion process, and the molecular mechanism underlying these interactions. Moreover, it is not known if the genes encoding for these Cryptosporidium proteins during the invasion process, proliferating asexual stages, and gametogenesis are essential for parasite survival. These challenges can now be overcome due to the availability of molecular tools to genetically manipulate the parasite genome and conditional protein degradation system that allows investigation of essential gene function [27•, 59].

On the host front, a key role of signaling and cytoskeletal remodeling resulting in accumulation of host filamentous actin upon Cryptosporidium invasion at the interface of this interaction has been reported [60,61,62,63]. Another cellular structure that has been identified is the membranous “feeder organelle” at this interface, and this organelle is thought to function in the uptake of host metabolites by the parasite. The parasite has reduced biochemical synthesis pathways and lacks enzymes for synthesis of amino acid, sugars, and nucleotides, but has many transporters encoded in its genome [34, 35, 64]. Although it has a highly streamlined metabolism, Cryptosporidium can directly acquire metabolites from the host or the gut environment. A recent study has identified neonatal mouse gut metabolites and their role in modulating C. parvum growth in vitro [65]. Medium or long-chain saturated fatty acids were reported to inhibit parasite growth, while omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids promoted parasite invasion and growth [65].

The parasite can also scavenge some precursor metabolites and encodes enzymes to convert these precursors and generate nucleotides, fatty acids, and amylopectin. Many of these conversion enzymes in Cryptosporidium such as the thymidine kinase (TK) and inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase (IMPDH) for nucleotide pathways and type I fatty acid synthesis enzymes have been acquired from bacteria via horizontal gene transfer making them attractive drug targets [66, 67]. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genetic manipulation of Cryptosporidium has allowed targeted deletion of genes encoding for TK and dihydrofolate reductase-thymidylate synthase (DHFR-TS) and revealed the role of TK in providing an alternative route to pyrimidine nucleotide synthesis in the absence of DHFR-TS [19••, 26, 68]. Also, multiple enzymes in the single purine nucleotide synthesis pathway such as IMPDH, GMP synthase (GMPS), adenosine kinase (AK), and the adenosine transporter (AT) can be genetically ablated without any effect on parasite growth, thus demonstrating that the parasite imports purine nucleotides from the host cell [26].

Animal models of infection to study virulence, host-parasite interactions, and disease pathogenesis

Neonatal calves can be naturally infected with C. parvum and thus serve as an ideal model to assess clinical illness signs of cryptosporidiosis. The calf model has been successfully used for evaluating the protection potential of colostrum, recombinant parasite proteins, and monoclonal antibodies in passive immunization studies as well as for testing the therapeutic efficacy of anti-cryptosporidial compounds [8, 69,70,71,72]. For C. hominis, the gnotobiotic piglet model of acute diarrhea has been the only available model for human cryptosporidiosis due to the high similarity of anatomy, physiology, and immunology between pigs and humans and clinical diarrheal signs [73].

Although these are efficient infection models for studying vaccine potential, they come with their own challenges such as requirement of specialized handling facilities for infection and challenge studies. On the flip side, small animal models such as immunocompromised IFN-γ KO mice that are relatively easy to handle are not suited to understand immune responses to Cryptosporidium infection and the key players that provide protection from disease. Thus, the lack of facile immunocompetent rodent models has been a major roadblock for evaluating the potential of putative virulence antigens in infectivity, disease pathogenesis, and immune protection. Moreover, there has been no single animal model that can be used to test for both C. parvum and C. hominis immunogens.

These two roadblocks have been overcome recently by breakthrough studies that report development of two animal models of infection, utilizing immunocompetent mice and rats to mimic human disease progression. The immunocompetent mouse model is based on using a naturally isolated and laboratory-adapted C. tyzzeri strain that can be genetically manipulated to track disease progression and study immune correlates of protection [20••]. Cryptosporidium tyzzeri strain infects the small intestine of C57BL/6 immunocompetent mice and closely resembles C. parvum and C. hominis in terms of its high sequence identity at the nucleotide level and similar intestinal pathology such as villus blunting, crypt hyperplasia, and lymphocyte aggregation as observed with human cryptosporidiosis.

Using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing, the C. tyzzeri strain was genetically engineered to create a reporter parasite strain that enabled measurement of parasite burden in mouse over time. This natural mouse model in which both host and parasite are genetically tractable has allowed to unravel the role of IFN-γ during early stage of infection and the pivotal role of T cells in parasite clearance [20••, 74]. Genetically engineered C. tyzzeri strains have also been instrumental in defining the innate mechanism for control of Cryptosporidium infection by NOD-like receptor family pyrin domain containing 6 (NLRP6) inflammasome dependent release of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-18 [75]. The C. tyzzeri mouse model will allow future studies to assess the immunogenic potential of vaccine candidate antigens by uncovering the key molecular interactions between the parasite and the host, immune responses to Cryptosporidium, and the immunoregulatory mechanisms that confer development of protective immunity.

Recently, an immunocompetent rat model for C. parvum and C. hominis has been developed for testing of future vaccine candidate antigens [22••]. This model used the intratracheal route to deliver C. parvum and C. hominis sporozoites to successfully infect tracheal epithelial cells and reported the generation of a Cryptosporidium-specific immune response. The systemic antigen-specific response was assessed by IFN-γ production, while the humoral immune response was evaluated by serum IgM and IgG production at day 10 and day 14 post infection. The applicability of this model for vaccine studies was evaluated by performing challenge studies. Rats infected with C. parvum sporozoites that had cleared infection showed complete protection against disease upon re-infection by intratracheal inoculation, thus demonstrating the suitability of this model for vaccine development [22••].

Conclusion

Advances in genetics, cell culture platforms, and new animal infection models are providing valuable insights into the basic biology of Cryptosporidium. These technological advancements will allow us to understand the molecular underpinnings of host-parasite interactions, mechanisms of generation of immune response against Cryptosporidium and disease pathogenesis, for the future development of a vaccine against cryptosporidiosis.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Khalil IA, Troeger C, Rao PC, et al. Morbidity, mortality, and long-term consequences associated with diarrhoea from Cryptosporidium infection in children younger than 5 years: a meta-analyses study. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e758–68.

Kotloff KL, Nataro JP, Blackwelder WC, et al. Burden and aetiology of diarrhoeal disease in infants and young children in developing countries (the Global Enteric Multicenter Study, GEMS): a prospective, case-control study. Lancet. 2013;382:209–22.

Platts-Mills JA, Babji S, Bodhidatta L, et al. Pathogen-specific burdens of community diarrhoea in developing countries: a multisite birth cohort study (MAL-ED). Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3:e564–75.

Kotloff KL, Nasrin D, Blackwelder WC, et al. The incidence, aetiology, and adverse clinical consequences of less severe diarrhoeal episodes among infants and children residing in low-income and middle-income countries: a 12-month case-control study as a follow-on to the Global Enteric Multicenter Study (GEMS). Lancet Glob Health. 2019;7:e568–84.

Korpe PS, Valencia C, Haque R, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors for cryptosporidiosis in children from 8 low-income sites: results from the MAL-ED study. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:1660–9.

Xiao L. Molecular epidemiology of cryptosporidiosis: an update. Exp Parasitol. 2010;124:80–9.

Santín M, Trout JM, Upton SJ. A longitudinal study of cryptosporidiosis in dairy cattle from birth to 2 years of age. Vet Parasitol. 2008;155:15–23.

Thomson S, Hamilton CA, Hope JC, Katzer F, Mabbott NA, Morrison LJ, et al. Bovine cryptosporidiosis: impact, host-parasite interaction and control strategies. Vet Res. 2017;48:42–16.

Santín M. Cryptosporidium and Giardia in ruminants. Vet Clin N Am Food Anim Pract. 2020;36:223–38.

Fayer R. The general biology of Cryptosporidium. In: Fayer R, Xiao L, editors. Cryptosporidium and Cryptosporidiosis. 2nd edition. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2007. p. 1–42.

Mac Kenzie WR, Hoxie NJ, Proctor ME, Gradus MS, Blair KA, Peterson DE, et al. A massive outbreak in Milwaukee of Cryptosporidium infection transmitted through the public water supply. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:161–7.

Widerström M, Schönning C, Lilja M, et al. Large outbreak of Cryptosporidium hominis infection transmitted through the public water supply, Sweden. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:581–9.

Jameson PB, Hung Y-T, Kuo CY, Bosela PA. Cryptosporidium Outbreak (Water Treatment Failure): North Battleford, Saskatchewan, Spring 2001. J Perform Constr Facil. 2008;22:342–7.

Checkley W, White AC, Jaganath D, et al. A review of the global burden, novel diagnostics, therapeutics, and vaccine targets for Cryptosporidium. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:85–94.

Innes EA, Chalmers RM, Wells B, Pawlowic MC. A one health approach to tackle cryptosporidiosis. Trends Parasitol. 2020;36:290–303.

Shahiduzzaman M, Daugschies A. Therapy and prevention of cryptosporidiosis in animals. Vet Parasitol. 2012;188:203–14.

Amadi B, Mwiya M, Musuku J, Watuka A, Sianongo S, Ayoub A, et al. Effect of nitazoxanide on morbidity and mortality in Zambian children with cryptosporidiosis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360:1375–80.

Amadi B, Mwiya M, Sianongo S, Payne L, Watuka A, Katubulushi M, et al. High dose prolonged treatment with nitazoxanide is not effective for cryptosporidiosis in HIV positive Zambian children: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:195.

•• Vinayak S, Pawlowic MC, Sateriale A, Brooks CF, Studstill CJ, Bar-Peled Y, et al. Genetic modification of the diarrhoeal pathogen Cryptosporidium parvum. Nature. 2015;523:477–80. Development of genetics for Cryptosporidium using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing and immunocompromised mouse infection model.

•• Sateriale A, Slapeta J, Baptista R, et al. A genetically tractable, natural mouse model of cryptosporidiosis offers insights into host protective immunity. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;26:135–146.e5.. Development of C. tyzzeri natural mouse model of cryptosporidiosis.

•• Wilke G, Funkhouser-Jones LJ, Wang Y, et al. A stem-cell-derived platform enables complete Cryptosporidium development in vitro and genetic tractability. Cell Host Microbe. 2019;26:123–134.e8. This study reports the development of air-liquid interface cultures derived from mouse intestinal epithelial stem cells for long-term propagation of Cryptosporidium.

•• Dayao DA, Sheoran A, Carvalho A, Xu H, Beamer G, Widmer G, et al. An immunocompetent rat model of infection with Cryptosporidium hominis and Cryptosporidium parvum. Int J Parasitol. 2020;50:19–22. This study describes the development of a rat model of infection for C. hominis and C. parvum.

•• Heo I, Dutta D, Schaefer DA, et al. Modelling Cryptosporidium infection in human small intestinal and lung organoids. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3:814–23. This study reports the development of organoid culture to propagate Cryptosporidium.

• Bhalchandra S, Lamisere H, Ward H. Intestinal organoid/enteroid-based models for Cryptosporidium. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2020;58:124–9. A recent comprehensive review on organoid and enteroid models for long-term propagation of Cryptosporidium.

Vinayak S, Jumani RS, Miller P, et al. Bicyclic azetidines kill the diarrheal pathogen Cryptosporidium in mice by inhibiting parasite phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase. Sci Transl Med. 2020;12:eaba8412.

Pawlowic MC, Somepalli M, Sateriale A, Herbert GT, Gibson AR, Cuny GD, et al. Genetic ablation of purine salvage in Cryptosporidium parvum reveals nucleotide uptake from the host cell. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:21160–5.

• Vinayak S. Recent advances in genetic manipulation of Cryptosporidium. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2020;58:146–52. A recent review that summarizes CRISPR/Cas9 editing of Cryptosporidium and new genetic advancements.

Current WL, Reese NC. A comparison of endogenous development of three isolates of Cryptosporidium in suckling mice. J Protozool. 1986;33:98–108.

Bouzid M, Hunter PR, Chalmers RM, Tyler KM. Cryptosporidium pathogenicity and virulence. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2013;26:115–34.

Barta JR, Thompson RCA. What is Cryptosporidium? Reappraising its biology and phylogenetic affinities. Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:463–8.

Valigurová A, Jirků M, Koudela B, Gelnar M, Modrý D, Slapeta J. Cryptosporidia: epicellular parasites embraced by the host cell membrane. Int J Parasitol. 2008;38:913–22.

Bartošová-Sojková P, Oppenheim RD, Ward GE, Lukes J. Epicellular apicomplexans: parasites “on the way in”. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1005080.

Aldeyarbi HM, Karanis P. The ultra-structural similarities between Cryptosporidium parvum and the gregarines. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 2016;63:79–85.

Abrahamsen MS, Templeton TJ, Enomoto S, et al. Complete genome sequence of the apicomplexan, Cryptosporidium parvum. Science. 2004;304:441–5.

Xu P, Widmer G, Wang Y, et al. The genome of Cryptosporidium hominis. Nature. 2004;431:1107–12.

Guérin A, Striepen B. The biology of the intestinal intracellular parasite Cryptosporidium. Cell Host Microbe. 2020;28:509–15.

Tandel J, English ED, Sateriale A, Gullicksrud JA, Beiting DP, Sullivan MC, et al. Life cycle progression and sexual development of the apicomplexan parasite Cryptosporidium parvum. Nat Microbiol. 2019;4:2226–36.

Wilke G, Ravindran S, Funkhouser-Jones L, Barks J, Wang Q, VanDussen KL, et al. Monoclonal antibodies to intracellular stages of Cryptosporidium parvum define life cycle progression in vitro. mSphere. 2018;3:957.

Funkhouser-Jones LJ, Ravindran S, Sibley LD. Defining stage-specific activity of potent new inhibitors of Cryptosporidium parvum growth in vitro. mBio. 2020;11:997.

Jumani RS, Hasan MM, Stebbins EE, et al. A suite of phenotypic assays to ensure pipeline diversity when prioritizing drug-like Cryptosporidium growth inhibitors. Nat Commun. 2019;10:1862.

Relat RMB, O'Connor RM. Cryptosporidium: host and parasite transcriptome in infection. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2020;58:138–45.

Li Y, Baptista RP, Kissinger JC. Noncoding RNAs in Apicomplexan Parasites: an update. Trends Parasitol. 2020;36:835–49.

Wang Y, Gong A-Y, Ma S, Chen X, Li Y, Su C-J, et al. Delivery of parasite RNA transcripts into infected epithelial cells during Cryptosporidium infection and its potential impact on host gene transcription. J Infect Dis. 2017;215:636–43.

Zhao G-H, Gong A-Y, Wang Y, Zhang X-T, Li M, Mathy NW, et al. Nuclear delivery of parasite Cdg2_FLc_0220 RNA transcript to epithelial cells during Cryptosporidium parvum infection modulates host gene transcription. Vet Parasitol. 2018;251:27–33.

Li M, Gong A-Y, Zhang X-T, Wang Y, Mathy NW, Martins GA, et al. Induction of a long noncoding RNA transcript, NR_045064, promotes defense gene transcription and facilitates intestinal epithelial cell responses against Cryptosporidium infection. J Immunol. 2018;201:3630–40.

DeCicco RePass MA, Chen Y, Lin Y, Zhou W, Kaplan DL, Ward HD. Novel bioengineered three-dimensional human intestinal model for long-term infection of Cryptosporidium parvum. Infect Immun. 2017;85:e00731–16.

Cardenas D, Bhalchandra S, Lamisere H, Chen Y, Zeng X-L, Ramani S, et al. Two- and three-dimensional bioengineered human intestinal tissue models for Cryptosporidium. Methods Mol Biol. 2020;2052:373–402.

Wanyiri J, Ward H. Molecular basis of Cryptosporidium–host cell interactions: recent advances and future prospects. Future Microbiol. 2006;1:201–8.

Riggs MW, Stone AL, Yount PA, Langer RC, Arrowood MJ, Bentley DL. Protective monoclonal antibody defines a circumsporozoite-like glycoprotein exoantigen of Cryptosporidium parvum sporozoites and merozoites. J Immunol. 1997;158:1787–95.

Barnes DA, Bonnin A, Huang JX, Gousset L, Wu J, Gut J, et al. A novel multi-domain mucin-like glycoprotein of Cryptosporidium parvum mediates invasion. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;96:93–110.

Cevallos AM, Zhang X, Waldor MK, Jaison S, Zhou X, Tzipori S, et al. Molecular cloning and expression of a gene encoding Cryptosporidium parvum glycoproteins gp40 and gp15. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4108–16.

Bhalchandra S, Ludington J, Coppens I, Ward HD. Identification and characterization of Cryptosporidium parvum Clec, a novel C-type lectin domain-containing mucin-like glycoprotein. Infect Immun. 2013;81:3356–65.

O'connor RM, Burns PB, Ha-Ngoc T, Scarpato K, Khan W, Kang G, et al. Polymorphic mucin antigens CpMuc4 and CpMuc5 are integral to Cryptosporidium parvum infection in vitro. Eukaryot Cell. 2009;8:461–9.

O'connor RM, Wanyiri JW, Cevallos AM, Priest JW, Ward HD. Cryptosporidium parvum glycoprotein gp40 localizes to the sporozoite surface by association with gp15. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;156:80–3.

Langer RC, Riggs MW. Cryptosporidium parvum apical complex glycoprotein CSL contains a sporozoite ligand for intestinal epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5282–91.

Perryman LE, Jasmer DP, Riggs MW, Bohnet SG, McGuire TC, Arrowood MJ. A cloned gene of Cryptosporidium parvum encodes neutralization-sensitive epitopes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;80:137–47.

Spano F, Putignani L, Naitza S, Puri C, Wright S, Crisanti A. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of a Cryptosporidium parvum gene encoding a new member of the thrombospondin family. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;92:147–62.

Smith HV, Nichols RAB, Grimason AM. Cryptosporidium excystation and invasion: getting to the guts of the matter. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:133–42.

Choudhary HH, Nava MG, Gartlan BE, Rose S, Vinayak S. A conditional protein degradation system to study essential gene function in Cryptosporidium parvum. mBio. 2020;11:e01231–20.

Forney JR, DeWald DB, Yang S, Speer CA, Healey MC. A role for host phosphoinositide 3-kinase and cytoskeletal remodeling during Cryptosporidium parvum infection. Infect Immun. 1999;67:844–52.

Elliott DA, Clark DP. Cryptosporidium parvum induces host cell actin accumulation at the host-parasite interface. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2315–22.

Chen X-M, Huang BQ, Splinter PL, Cao H, Zhu G, McNiven MA, et al. Cryptosporidium parvum invasion of biliary epithelia requires host cell tyrosine phosphorylation of cortactin via c-Src. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:216–28.

Chen X-M, Splinter PL, Tietz PS, Huang BQ, Billadeau DD, LaRusso NF. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and frabin mediate Cryptosporidium parvum cellular invasion via activation of Cdc42. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31671–8.

Rider SD, Zhu G. Cryptosporidium: genomic and biochemical features. Exp Parasitol. 2010;124:2–9.

VanDussen KL, Funkhouser-Jones LJ, Akey ME, Schaefer DA, Ackman K, Riggs MW, et al. Neonatal mouse gut metabolites influence Cryptosporidium parvum infection in intestinal epithelial cells. mBio. 2020;11:e02582–20.

Striepen B, Pruijssers AJP, Huang J, Li C, Gubbels M-J, Umejiego NN, et al. Gene transfer in the evolution of parasite nucleotide biosynthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:3154–9.

Zhu G, Li Y, Cai X, Millership JJ, Marchewka MJ, Keithly JS. Expression and functional characterization of a giant type I fatty acid synthase (CpFAS1) gene from Cryptosporidium parvum. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;134:127–35.

Pawlowic MC, Vinayak S, Sateriale A, Brooks CF, Striepen B. Generating and maintaining transgenic Cryptosporidium parvum parasites. Curr Protocol Microbiol. 2017;46:20B.2.1–20B.2.32.

Burton AJ, Nydam DV, Jones G, Zambriski JA, Linden TC, Cox G, et al. Antibody responses following administration of a Cryptosporidium parvum rCP15/60 vaccine to pregnant cattle. Vet Parasitol. 2011;175:178–81.

Askari N, Shayan P, Mokhber-Dezfouli MR, Ebrahimzadeh E, Lotfollahzadeh S, Rostami A, et al. Evaluation of recombinant P23 protein as a vaccine for passive immunization of newborn calves against Cryptosporidium parvum. Parasite Immunol. 2016;38:282–9.

Riggs MW, Schaefer DA. Calf clinical model of cryptosporidiosis for efficacy evaluation of therapeutics. Methods Mol Biol. 2020;2052:253–82.

Perryman LE, Kapil SJ, Jones ML, Hunt EL. Protection of calves against cryptosporidiosis with immune bovine colostrum induced by a Cryptosporidium parvum recombinant protein. Vaccine. 1999;17:2142–9.

Lee S, Beamer G, Tzipori S. The piglet acute diarrhea model for evaluating efficacy of treatment and control of cryptosporidiosis. Hum Vaccine Immunother. 2019;15:1445–52.

Marzook NB, Sateriale A. Crypto-Currency: investing in new models to advance the study of Cryptosporidium infection and immunity. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2020;10:441.

Sateriale A, Gullicksrud JA, Engiles JB, et al. The intestinal parasite Cryptosporidium is controlled by an enterocyte intrinsic inflammasome that depends on NLRP6. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;118:1–8.

Funding

Our research is supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health (R21AI142380) and start-up funds from the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign to S.V.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Derek Pinto and Sumiti Vinayak declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Parasitology

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pinto, D.J., Vinayak, S. Cryptosporidium: Host-Parasite Interactions and Pathogenesis. Curr Clin Micro Rpt 8, 62–67 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40588-021-00159-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40588-021-00159-7