Abstract

Purpose of Review

To summarize findings about the emergence and characteristics of canonical babbling in children with late detected developmental disorders (LDDDs), such as autism spectrum disorder, Rett syndrome, and fragile X syndrome. In particular, we ask whether infants’ vocal development in the first year of life contains any markers that may contribute to earlier detection of these disorders.

Recent Findings

Only a handful studies have investigated canonical babbling in infants with LDDDs. With divergent research paradigms and definitions applied, findings on the onset and characteristics of canonical babbling are inconsistent and difficult to compare. Infants with LDDDs showed reduced likelihood to produce canonical babbling vocalizations. If achieved, this milestone was more likely to be reached beyond the critical time window of 5–10 months.

Summary

Canonical babbling appears promising as a potential marker for early detection of infants at risk for developmental disorders. In-depth studies on babbling characteristics in LDDDs are warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Speech-language acquisition typically follows a defined domain-specific pathway cascading from one milestone to the next one, increasing in complexity, accuracy, and stability. During the first year of life, infants’ receptive and productive capacities develop from being universal to language-specific [1,2,3,4]. Early vocal development follows a sequence to build up our complex human speech capacity [5,6,7,8,9,10,11] as well as language and socio-communicative functions (e.g., lexical acquisition, phonological awareness, literacy skills [12,13,14,15]). Irrespective of differences in underlying theoretical linguistic frameworks or explanatory models, there is agreement that it all starts with the first cry, followed by the production of vegetative and quasi resonant sounds before the first cooing sounds occur at around 3 months of age. Infants typically move on to produce fully resonant sounds, raspberries, and marginal syllables, and then canonical syllables which form the basis of first spoken words that usually appear around the first birthday. In the second year of life, complexity of vocal production increases [9,10,11, 16], and the initially rather slow growth of the expressive vocabulary rapidly increases to a vocabulary spurt or similar fast-mapping related vocabulary growth patterns and first word combinations [17,18,19,20]. The continuously increasing proficiency of the speech-language and communicative capacity across all linguistic levels—phonetics, phonology, semantics, morphology, syntax, and pragmatics—leads up to evolving fairly competent speakers at school age.

The most prominent and among the most extensively studied speech-language milestones before the first spoken words is the emergence of canonical syllables [3, 7, 21, 22•]. In contrast to precanonical vocalizations (e.g., quasi-resonant sounds, cooing sounds, fully-resonant sounds or raspberries), canonical syllables consist of a consonant- and a vowel-like part. Additionally, canonical syllables are target-language-like and thus differ from marginal syllables, which are produced with slow or erratic formant transitions [7, 11, 23]. Canonical babbling is characterized by syllables with at least one vowel-like element and one supraglottal consonant-like element with a rapid, adult-like formant transition between consonant and vowel (phonetical representation: e.g., [ba], [di], [ata], [nunu], [dada]; [24, 25]). The rapid transition between consonants and vowels is a defining feature of the difference between precanonical and canonical syllable productions. Infants gradually develop the oral-motor skills necessary to produce adult-like consonant-vowel-syllables, which, in turn, are the prerequisite to uttering conventional words [7, 26]. Another characteristic of vocalizations in the babbling period is multisyllabicity [8, 21]. Notably, some authors have differentiated between reduplicated (e.g., [dada], [mamamam]) and variegated babbling (e.g., [abababedada]; [5, 6]) while others have subsumed both under the term canonical babbling [11]. Given this inconsistence in terminology, in this paper, we use the term canonical babbling to embrace single consonant-vowel-syllables as well as disyllables and strings of syllables, either reduplicated or variegated.

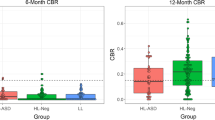

In addition to these divergent definitions, there are also inconsistencies in the parameters chosen to define the onset of canonical babbling. While some researchers used the definition of a consonant-vowel-syllable with rapid transition between the consonant and the vowel and defined a canonical babbling ratio (CBR) of 0.20 (CBRutt = number of canonical syllables/total number of utterances; [27]) or 0.15 (CBRsyl = number of canonical syllables/total number of syllables; [28] and CBRUTTER = number of utterances containing canonical syllables/total number of utterances; [29]) as the onset, others considered canonical babbling as established if at least one or two canonical syllables or strings of canonical syllables occur in a speech sample of 10–45 min length [21, 30, 31]. Additionally, Schauwers et al. suggested a stability parameter required for the establishment of the canonical babbling phase defined through the presence of at least two vocalizations with multiple articulatory movements in one respiration cycle over three consecutive months [31], labeled MULTI by Molemans et al. [32]. Also, studies differ, for example, in whether to include [11, 27, 28] or exclude the approximants [ʋ] and [j] as true consonants in canonical syllables [33, 34]. Based on the exclusion of these phonetic realizations, a true canonical babbling ratio (TCBR) of 0.20 (TCBRutt = number of true canonical syllables/total number of utterances; [32]) and 0.15 (TCBRsyl = number of true canonical syllables/total number of syllables; [34]) was proposed as onset measurement.

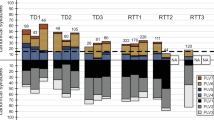

Nevertheless, based on parental reports and video-analysis at home or in laboratory settings, canonical babbling onset (CBO) in typically developing (TD) infants has been observed between 5 and 10 months of age [6, 35]. Moreover, this age range for CBO appears to be relatively consistent across languages, as reported for English, Dutch, Swedish, Spanish, and German, to name but a few [9,10,11, 32, 36]. Data from Mandarin- or Cantonese-learning infants revealed a similar age range of CBO [37], with slightly higher CBRsyl-values as compared to English-learning infants [38••]. Thus, like many other developmental phenomena, age of CBO may reveal considerable individual variation, while nevertheless pointing to a critical window before 10 months of age. The conditions that lead to late babbling may set off a cascade, negatively affecting a variety of additional linguistic capabilities down the road. The core problem that causes late babbling could generalize to other aspects of language and literacy development. Thus, the absence of canonical babbling and persistence of precanonical vocalizations as the predominant vocalization pattern beyond 10–12 months of age may indicate atypical vocal development and precede later speech and language deviations [25, 39]. Indeed, Oller et al. reported that infants who did not produce canonical syllables at 10–12 months also had a reduced expressive vocabulary at 18, 24, and 30 months of age [24]. Eilers and Oller found that infants with hearing impairment failed to produce canonical syllables until 11 months of age, while all TD infants reached this milestone by 10 months [35]. Delayed or deviant babbling in infants with hearing impairment has also been reported in other studies [40,41,42,43,44]. A later onset of canonical babbling has also been observed in other developmental disorders such as in infants with Williams syndrome [45, 46], Cri du Chat syndrome [47], and childhood apraxia of speech ([48]). Interestingly, in infants with Down syndrome, evidence exists both for and against a delay in CBO [49,50,51,52], suggesting that achieving the canonical babbling milestone within the critical time window does not necessarily lead to typical speech and language outcome.

While Down syndrome can be identified prior to or at birth, and early developmental profiles can thereafter be easily documented, great challenges arise when dealing with developmental disorders commonly diagnosed beyond toddlerhood. Prodromal development in babbling has received much less attention in late detected developmental disorders (LDDDs), such as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), Rett syndrome (RTT), and fragile X syndrome (FXS). The methodological difficulties of looking back on the pre-diagnostic development are further exacerbated by the fact that many LDDDs are also rare diseases, leaving few participants available for investigation [53,54,55, 56••]. Nonetheless, as delayed or atypical babbling is often associated with later verbal deficits [24, 25, 33, 57], infants with LDDDs and associated speech-language and socio-communicative deficits may well exhibit peculiarities in vocal development early in life. Understanding typical and atypical characteristics and trajectories of vocal development in the first year of life may in turn contribute to detecting these LDDDs at an earlier time. In a recent paper, Roche et al. reviewed studies on early vocalizations of infants with such LDDDs [58••]. While not exclusively focused on babbling, the authors suggested a reduced likelihood that infants with LDDDs would reach the canonical babbling stage. In this article, we chose to focus on infants later diagnosed with ASD, RTT, and FXS—conditions sharing deviances in speech-language and socio-communicative development. We aim to provide an overview of studies investigating the onset and characteristics of canonical babbling in children with these LDDDs. We highlight the importance of investigating such early markers which may prove to be valuable components of early screening and diagnosis of infants at risk for developmental disorders.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Autism spectrum disorder is a developmental disorder characterized by persistent deficits in social interaction and communication, and the presence of restrictive and repetitive behaviors [59]. In the USA, ASD prevalence was reported to be 16.8 in 1000 children aged 8 years [60]. The specific causes driving the atypical neurodevelopment of ASD remain poorly understood. A number of candidate genes (e.g., NRXN, PTCHD1, SHANK; [61]) as well as environmental factors (e.g., maternal infections or medication during pregnancy, advanced parental age, environmental pollutants; [62, 63] are assumed to play a role in the etiology of ASD. A recent parent survey found the mean age of ASD diagnosis remains rather late in the toddlerhood [64].

Studies on the emergence and production of canonical babbling in infants later diagnosed with ASD report inconsistent findings, in part, due to the different research methods applied and definitions used. For example, Werner et al. retrospectively analyzed home videos and found no different frequencies of canonical syllables per minute between the ASD and the control group at 8–10 months, yet found a group difference at 12 months in frequencies of complex babbling [65]. Chericoni et al., also using retrospective video analysis (RVA), studied infants from 0 to 18 months. They categorized infants’ vocal behaviors into four groups: (1) vocalizations (vowels or non-reduplicated consonants and vowels), (2) long reduplicated babbling (three or more units), (3) two-syllable babbling, and (4) first words [66]. In contrast to the previous findings by Werner et al., while between 6 and 12 months, infants with ASD and TD infants did not differ in rate (counts per minute) of producing canonical syllables (i.e., group (2) and (3)), infants with ASD produced less precanonical vocalizations (i.e., group (1)) than the controls. In yet another RVA study, however, Patten et al. calculated the CBRs of infants aged 9–12 and 15–18 months [67]. They found significantly lower CBRs and lower volubility for the infants with ASD compared to TD controls. In a prospective study, Paul et al. examined vocalizations in infants with an older sibling diagnosed with ASD (i.e., the high-risk group) [68]. They investigated the percentage of canonical syllables (number of true consonant-vowel-syllables/total number of speech-like vocalizations) and found a significantly lower CBR at 9 months in the high-risk group than in the low-risk controls. At the age of 12 months, however, this difference disappeared. In another prospective study, Pokorny et al. reported that out of ten infants with ASD aged 10 months, four produced vocalizations more complex than single canonical syllables, which was comparable to typical controls [69•]. Neither did the authors find a significant difference in volubility of overall vocalizations between the two groups. LeBarton and Iverson videotaped infants at high risk for ASD with their primary caregivers monthly between 5 and 14 months of age [70]. They found that 33 of 37 infants at high risk for ASD reached the canonical babbling milestone (i.e., first observation of reduplicative babbling). Mean onset age of canonical babbling was 7.67 months (SD 1.76, range 5–12). Iverson and Wozniak, on the other hand, found a mean onset age of canonical babbling (i.e., regular use of reduplicative babbling) between 5 and 18 months for high-risk infants and between 5 and 9 months for low-risk controls, with a significantly higher portion of the high-risk infants showing a CBO at the later end of the age range [71]. In sum, while infants with ASD often achieve the canonical babbling milestone, the onset time, rate, and other characteristics of their babbling development frequently reveal deviations.

Rett Syndrome (RTT)

Rett syndrome is an X-linked genetic disorder with a prevalence of approximately 1 in 10,000 female births [72]. The main genetic cause of RTT are de novo mutations in the Methyl-CpG-binding protein 2 gene (MECP2; [73]). For a long time, RTT was characterized by a rather inconspicuous early development followed by the partial or complete loss of already acquired purposeful hand skills and spoken language. However, as MECP2 mutations potentially affect prenatal and postnatal brain development [74, 75], a perspective change was called for to acknowledge an earlier onset of symptoms opposing the typical early development assumption [76,77,78,79,80,81,82]. Based on the consensus criteria released in 2010, RTT is divided into typical/classic and atypical RTT/variants [81]. A relatively mild RTT phenotypical appearance associated with comparably better speech-language capacities (i.e., use of a number of single words or even word combinations/phrases) than seen in typical RTT, relatively better functional hand use, and milder intellectual disability is the preserved speech variant (PSV; [81, 83,84,85]). Still, individuals with PSV follow an atypical speech-language development including the loss of acquired functions [79, 82, 85, 86]. The current mean age of diagnosis is 2.7 years for typical RTT and 3.8 years for atypical RTT [87].

Systematic research on early vocalizations in general and canonical babbling in particular in individuals with RTT is scarce. When parents were asked to recall their child’s earlier development, the majority were convinced that the child had produced canonical babbling or first words prior to regression [88, 89]. More objective analyses utilizing RVA to assess canonical babbling, to the best of our knowledge, has been described in only three studies [79, 90, 91]. Overall, results revealed that girls with RTT show poor verbal development and they are likely to achieve the canonical syllables milestone with delay, if at all. Out of six infants with PSV (four Italian- and two German-speaking) investigated by Marschik et al., five failed to produce well-formed syllables/canonical babbling-like vocalizations until 12 months of age [90], two did not show CB until the second birthday, and only one girl of the six infants in this study produced canonical babbling at an age of 7 months, which falls within the typical age range. This girl achieved extraordinarily high language proficiency very rarely seen in RTT [86, 92]. Einspieler et al. studied a pair of monozygotic twins with typical RTT (Portuguese-speaking) [91]. They did not observe canonical babbling until the children were 21 months. A third study revealed that six out of 15 individuals with RTT did not produce any canonical babbling during their first 24 months of life [79]. While half of the infants with typical RTT reached this milestone (5/10 cases), the proportion was significantly higher in the comparably milder PSV (4/5 cases). It is important to note that the authors not only reported absence or delay of achieving expressive verbal milestones but also qualitative differences or typical vocalizations interspersed with atypical phonetic realizations (e.g., vocalizations on inspiratory airstream, high pitched crying; [79, 90, 91, 93, 94]. As only retrospective studies on vocal behaviors could be conducted thus far, the age of CBO in RTT is yet to be determined, since complete sampling is not obtainable. Also, CBRs or volubility counts have not been reported for RTT to date. In sum, a proportion of infants with RTT do reach the canonical babbling stage, yet the majority of them experiences considerable deviation and delay.

Fragile X Syndrome (FXS)

Fragile X syndrome is the leading cause of inherited intellectual disability and the most common monogenic cause of ASD [95,96,97,98]. FXS was estimated to occur in 1 of 5000 males and in 1 of 4000 to 8000 females [99]. FXS results from the excessive repeat of a trinucleotide CGG at the Xq 27.3 site on the Fragile X Mental Retardation-1 gene (FMR1; [98, 100]). The mean age of FXS diagnosis remains at about 3 years [101].

To the best of our knowledge, only two RVA studies have investigated babbling in infants with FXS [102•, 103•]. In one study, two out of seven infants (5 monolingual German-, 2 bilingual German-Spanish-speaking) were found to produce canonical babbling between 9 and 12 months of age [103]. In the other study, none of the ten infants (English-speaking households) reached the milestone of canonical babbling (defined as reaching or exceeding a CBRsyl of .15; [102•]). In this study, however, eight of the 14 typically developing controls aged 9–12 months also failed to reach this milestone.

Discussion

With this paper, we aimed to provide an overview of studies on canonical babbling in infants with late diagnosed developmental disorders. We exemplarily chose ASD, RTT, and FXS, as all these LDDDs are speech- and language-related disorders. Leaving aside issues of methodological differences and definitions used for the relevant measures, the few existent studies reviewed here suggest that infants with ASD, RTT, or FXS are likely to show deviant patterns of babbling development compared to TD infants.

To understand the prediagnostic development of LDDDs, many researchers have relied on RVA for good reasons [54]. It is only in the last decade that prospective studies have boomed rapidly, providing us novel opportunities to investigate speech-language development from early on (i.e., high-risk ASD studies). As has been discussed elsewhere, RVA inherently suffers from sampling limits [54, 104, 105], making determination of the onset and the presence/absence of a specific behavior (e.g., canonical babbling) elusive. While prospective studies are certainly the method of choice to study high-risk cohorts, less prevalent disorders or disorders with unknown etiology or without hereditary pathways will—at least for now—still be studied applying retrospective approaches.

Findings of the scarce babbling studies on ASD, RTT, and FXS were, in the face of all methodological difficulties, in line with previous studies investigating infants with or at risk for developmental disorders [24, 25, 33, 57]. The production of canonical syllables is an essential and necessary step in a child’s pathway to the spoken world. A delayed CBO or deviant canonical babbling pattern appeared to be a precursor of further atypical speech-language development. Notably, in all our targeted groups (i.e., ASD, RTT, and FXS), there were infants who did achieve the babbling milestones within the typical time window. This suggests that although absent or delayed canonical babbling proved alarming, the presence of babbling before 10 months of age does not predict later intact speech and language skills. It remains possible that adverse characteristics of this early vocal behavior might hide behind a timely CBO, and qualitative distinctions in babbling may associate with the severity of later language deficits. This deserves further in-depth research with more advanced methodology.

Deviances or delay in canonical babbling is highly specific but not sensitive enough to refer to atypical language development. A deficit in early development, however unfortunately, appears seldom alone. A deleterious sign might often precede or coexist with the others. As distressful as it can be for the individual of concern, if one sign appears subtle or elusive, multiple signs within and across domains might flag atypical development of an infant to caregivers and practitioners, which solicits earlier detection and intervention.

Conclusions

The increasing evidence of “babbling-alterations” in infants with LDDDs indicated that canonical babbling, as one of several milestones bootstrapping speech-language development, may prove to be another valuable marker for earlier detection of these disorders. Beyond the investigation of the presence or absence, and the onset age of canonical babbling in infants with LDDDs, it might be of clinical importance to examine the potential qualitative differences of infant babbling and its relation to later language outcomes. Upcoming research may benefit from capturing acoustic representations of babbling and other infant vocal behaviors in LDDDs [56••, 69•, 94, 106,107,108,109]. Combining concurrent audio signal processing methods with machine learning technology [110] is a promising approach for objective automated recognition of peculiarities and deviances in atypical development. Future systematic approaches netting canonical babbling and other markers in early development may facilitate better understanding and timely identification of different pathways leading to specific disorders.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Kuhl PK. Early language acquisition: cracking the speech code. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(11):831–43. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1533.

Jusczyk PW. The discovery of spoken language. Cambridge: MIT-Press; 1997.

Vihman MM. Phonological development: the first two years. 2nd ed. Wiley-Blackwell: Malden; 2014.

Werker JF, Hensch TK. Critical periods in speech perception: new directions. Annu Rev Psychol. 2015;66:173–96. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015104.

Stark RE. Stages of speech development in the first year of life. In: Yeni-Komshian G, Kavanagh JF, Ferguson CA, editors. Child phonology. New York: Academic Press; 1980. p. 73–90.

Oller DK. The emergence of sounds of speech in infancy. In: Yeni-Komshian G, Kavanagh JF, Ferguson CA, editors. Child phonology. New York: Academic Press; 1980. p. 93–112.

Oller DK. The emergence of the speech capacity. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2000.

Koopmans-van Beinum FJ, van der Stelt JM. Early stages in the development of speech movements. In: Lindblom B, Zetterström R, editors. Precursors of early speech. New York: Stockton; 1986. p. 37–50.

Roug L, Landberg I, Lundberg LJ. Phonetic development in early infancy: a study of four Swedish children during the first eighteen months of life. J Child Lang. 1989;16(1):19–40.

Papousek M. Vom ersten Schrei zum ersten Wort. Anfänge der Sprachentwicklung in der vorsprachlichen Kommunikation. Bern: Hans Huber; 1994.

Nathani S, Ertmer DJ, Stark RE. Assessing vocal development in infants and toddlers. Clin Linguist Phon. 2006;20(5):351–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699200500211451.

Vihman MM, DePaolis RA, Keren-Portnoy T. The role of production in infant word learning. Lang Learn. 2014;64(s2):121–40.

McCune L, Vihman MM. Early phonetic and lexical development: a productivity approach. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2001;44(3):670–84.

Mann VA, Foy JG. Speech development patterns and phonological awareness in preschool children. Ann Dyslexia. 2007;57(1):51–74.

Farquharson K, Hogan TP, Hoffman L, Wang J, Green KF, Green JR. A longitudinal study of infants’ early speech production and later letter identification. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0204006. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0204006.

De Boysson-Bardies B, Vihman MM. Adaptation to language: evidence from babbling and first words in four languages. Language. 1991;67:297–319.

Hirsh-Pasek K, Golinkoff RM, Hollich G. An emergentist coalition model for word learning: mapping words to objects is a product of the interaction of multiple cues. In: Golinkoff RM, Hirsh-Pasek K, Bloom L, Smith LB, Woodward AL, Akhtar N, et al., editors. Becoming a word learner: a debate on lexical acquisition. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. p. 136–64.

Kauschke C, Hofmeister C. Early lexical development in German: a study on vocabulary growth and vocabulary composition during the second and third year of life. J Child Lang. 2002;29:735–57. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000902005330.

Marschik PB, Einspieler C, Garzarolli B, Prechtl HF. Events at early development: are they associated with early word production and neurodevelopmental abilities at the preschool age? Early Hum Dev. 2007;83(2):107–14.

Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Bates E, Thal DJ, Pethick SJ. Variability in early communicative development. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 1994;59(5):1–185.

Fagan MK. Mean length of utterance before words and grammar: longitudinal trends and developmental implications of infant vocalizations. J Child Lang. 2009;36(3):495–527. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000908009070.

• Morgan L, Wren YE. A systematic review of the literature on early vocalizations and babbling patterns in young children. Commun Disord Q. 2018;40(1):3–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740118760215. Recent systematic review on canonical babbling between 9 and 18 months of age.

Nathani S, Oller DK. Beyond ba-ba and gu-gu: challenges and strategies in coding infant vocalizations. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2001;33(3):321–30.

Oller DK, Eilers RE, Neal AR, Schwartz HK. Precursors to speech in infancy: the prediction of speech and language disorders. J Commun Disord. 1999;32(4):223–45.

Oller DK, Eilers RE, Neal AR, Cobo-Lewis AB. Late onset canonical babbling: a possible early marker of abnormal development. Am J Ment Retard. 1998;103(3):249–63. https://doi.org/10.1352/0895-8017(1998)103<0249:locbap>2.0.co;2.

Stoel-Gammon C. Prelinguistic vocal development: measurement and predictions. In: Ferguson CA, Menn L, Stoel-Gammon C, editors. Phonological development: models, research, implications. Timonium: York Press, Inc.; 1992. p. 439–56.

Oller DK, Eilers RE. The role of audition in infant babbling. Child Dev. 1988;59(2):441–9.

Oller DK, Eilers RE, Steffens ML, Lynch MP, Urbano R. Speech-like vocalizations in infancy: an evaluation of potential risk factors. J Child Lang. 1994;21(1):33–58.

Nyman A, Lohmander A. Babbling in children with neurodevelopmental disability and validity of a simplified way of measuring canonical babbling ratio. Clin Linguist Phon. 2018;32(2):114–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699206.2017.1320588.

Schramm B, Bohnert A, Keilmann A. The prelexical development in children implanted by 16 months compared with normal hearing children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(12):1673–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.08.023.

Schauwers K, Gillis S, Daemers K, De Beukelaer C, Govaerts PJ. Cochlear implantation between 5 and 20 months of age: the onset of babbling and the audiologic outcome. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25(3):263–70.

Molemans I, Van den Berg R, Van Severen L, Gillis S. How to measure the onset of babbling reliably? J Child Lang. 2012;39(3):523–52. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000911000171.

Stoel-Gammon C. Prespeech and early speech development of two late talkers. First Lang. 1989;9:207–24.

Chapman KL, Hardin-Jones M, Schulte J, Halter KA. Vocal development of 9-month-old babies with cleft palate. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2001;44:1268–83.

Eilers RE, Oller DK. Infant vocalizations and the early diagnosis of severe hearing impairment. J Pediatr. 1994;124(2):199–203.

Karousou A, López-Ornat S. Prespeech vocalizations and the emergence of speech: a study of 1005 spanish children. Span J Psychol. 2013;16(e32):1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2013.27.

Chen LM, Kent RD. Segmental production in mandarin-learning infants. J Child Lang. 2010;37(2):341–71. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0305000909009581.

•• Lee CC, Jhang Y, Relyea G, Chen LM, Oller DK. Babbling development as seen in canonical babbling ratios: a naturalistic evaluation of all-day recordings. Infant Behav Dev. 2018;50:140–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2017.12.002. Presents a novel prospective approach to study infants vocalizations.

Lohmander A, Holm K, Eriksson S, Lieberman M. Observation method identifies that a lack of canonical babbling can indicate future speech and language problems. Acta Paediatr. 2017;106(6):935–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13816.

von Hapsburg D, Davis BL. Auditory sensitivity and the prelinguistic vocalizations of early-amplified infants. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2006;49(4):809–22. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2006/057).

Koopmans-van Beinum FJ, Clement CJ, van den Dikkenberg-Pot I. Babbling and the lack of auditory speech perception: a matter of coordination? Dev Sci. 2001;4(1):61–70.

Moeller MP, Hoover B, Putman C, Arbataitis K, Bohnenkamp G, Peterson B, et al. Vocalizations of infants with hearing loss compared with infants with normal hearing: part I - phonetic development. Ear Hear. 2007;28(5):605–27.

Nathani Iyer S, Oller DK. Prelinguistic vocal development in infants with typical hearing and infants with severe-to-profound hearing loss. Volta Rev. 2008;108(2):115–38.

Shehata-Dieler W, Ehrmann-Mueller D, Wermke P, Voit V, Cebulla M, Wermke K. Pre-speech diagnosis in hearing-impaired infants: how auditory experience affects early vocal development. Speech Lang Hear. 2013;16(2):99–106. https://doi.org/10.1179/2050571X13Z.00000000011.

Masataka N. Why early linguistic milestones are delayed in children with Williams syndrome: late onset of hand banging as a possible rate-limiting constraint on the emergence of canonical babbling. Dev Sci. 2001;4:158–64.

Velleman SL, Currier A, Caron T, Curley A, editors. Phonological development in Williams syndrome. Annual meeting of the ICPLA; 2006 31 May - 3 June; Dubrovnik, Croatia.

Sohner L, Mitchell P. Phonatory and phonetic characteristics of prelinguistic vocal development in cri du chat syndrome. J Commun Disord. 1991;24(1):13–20.

Overby M, Caspari SS. Volubility, consonant, and syllable characteristics in infants and toddlers later diagnosed with childhood apraxia of speech: a pilot study. J Commun Disord. 2015;55:44–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcomdis.2015.04.001.

Cobo-Lewis AB, Oller DK, Lynch MP, Levine SL. Relations of motor and vocal milestones in typically developing infants and infants with Down syndrome. Am J Ment Retard. 1996;100(5):456–67.

Lynch MP, Oller DK, Steffens ML, Levine SL, Basinger DL, Umbel V. Onset of speech-like vocalizations in infants with Down syndrome. Am J Ment Retard. 1995;100(1):68–86.

Steffens ML, Oller DK, Lynch M, Urbano RC. Vocal development in infants with Down syndrome and infants who are developing normally. Am J Ment Retard. 1992;97(2):235–46.

Kent RD, Vorperian HK. Speech impairment in Down syndrome: a review. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2013;56(1):178–210. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2012/12-0148).

Marschik PB, Einspieler C, Sigafoos J, Enzinger C, Bölte S. The interdisciplinary quest for behavioral biomarkers pinpointing developmental disorders. Dev Neurorehabil. 2016;19(2):73–4.

Marschik PB, Einspieler C. Methodological note: video analysis of the early development of Rett syndrome--one method for many disciplines. Dev Neurorehabil. 2011;14(6):355–7.

Ozonoff S, Young GS, Carter A, Messinger D, Yirmiya N, Zwaigenbaum L, et al. Recurrence risk for autism spectrum disorders: a baby siblings research consortium study. Pediatrics. 2011;128:488–95.

•• Marschik PB, Pokorny FB, Peharz R, Zhang D, O’Muircheartaigh J, Roeyers H, et al. A novel way to measure and predict development: a heuristic approach to facilitate the early detection of neurodevelopmental disorders. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2017;17(43). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-017-0748-8. Presents a multidisciplinary approach to enhance early detection of neurodevelopmental disorders.

Stark RE, Ansel BM, Bond J. Are prelinguistic abilities predic tive of learning disability? A follow-up study. In: Masland RL, Masland M, editors. Preschool prevention of reading failure. Parkton: York Press; 1988.

•• Roche L, Zhang D, Bartl-Pokorny KD, Pokorny FB, Schuller BW, Esposito G, et al. Early vocal development in autism spectrum disorder, Rett syndrome, and fragile X syndrome: insights from studies using retrospective video analysis. Adv Neurodev Disord. 2018;2(1):49–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41252-017-0051-3. Comprehensive review on early verbal development in late detected developmental disorders.

Bölte S, Hallmayer J. Autism spectrum conditions. Cambridge: Hogrefe; 2011.

Baio J, Wiggins L, Christensen DL, Maenner MJ, Daniels J, Warren Z, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years – autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep Surveill Summ. 2018;67(6):1–23.

Human Gene Module. https://gene.sfari.org/database/human-gene/. Accessed April 9, 2019.

Karimi P, Kamali E, Mousavi SM, Karahmadi M. Environmental factors influencing the risk of autism. J Res Med Sci. 2017;22:27.

Bölte S, Girdler S, Marschik PB. The contribution of environmental exposure to the etiology of autism spectrum disorder. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2019;76(7):1275–97.

Sicherman N, Loewenstein G, Tavassoli T, Buxbaum JD. Grandma knows best: family structure and age of diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder. Autism. 2018;22(3):368–76.

Werner E, Dawson G, Osterling J, Dinno N. Brief report: recognition of autism spectrum disorder before one year of age: a retrospective study based on home videotapes. J Autism Dev Disord. 2000;30:157–62.

Chericoni N, de Brito Wanderley D, Costanzo V, Diniz-Goncalves A, Leitgel Gille M, Parlato E, et al. Pre-linguistic vocal trajectories at 6-18 months of age as early markers of autism. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1595. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01595.

Patten E, Belardi K, Baranek GT, Watson LR, Labban JD, Oller DK. Vocal patterns in infants with autism spectrum disorder: canonical babbling status and vocalization frequency. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(10):2413–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2047-4.

Paul R, Fuerst Y, Ramsay G, Chawarska K, Klin A. Out of the mouths of babes: vocal production in infant siblings of children with ASD. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52(5):588–98. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02332.x.

• Pokorny FB, Schuller BW, Marschik PB, Brueckner R, Nyström P, Cummins N, et al. Earlier identification of children with autism spectrum disorder: an automatic vocalisation-based approach. Proc Interspeech. 2017:309–13. This study evaluates the feasibility of automatic identification of 10-months-old infants with ASD.

LeBarton ES, Iverson JM. Associations between gross motor and communicative development in at-risk infants. Infant Behav Dev. 2016;44:59–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2016.05.003.

Iverson JM, Wozniak RH. Variation in vocal-motor development in infant siblings of children with autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(1):158–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0339-z.

Laurvick CL, de Klerk N, Bower C, Christodoulou J, Ravine D, Ellaway C, et al. Rett syndrome in Australia: a review of the epidemiology. J Pediatr. 2006;148(3):347–52.

Amir RE, Van den Veyver IB, Wan M, Tran CQ, Francke U, Zoghbi HY. Rett syndrome is caused by mutations in X-linked MECP2. Nat Genet. 1999;23(2):185–8.

Guy J, Cheval H, Selfridge J, Bird A. The role of MeCP2 in the brain. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:631–52.

Feldman D, Banerjee A, Sur M. Developmental dynamics of Rett syndrome. Neural Plast. 2016.

Einspieler C, Kerr AM, Prechtl HFR. Is the early development of girls with Rett disorder really normal? Pediatr Res. 2005;57:696–700.

Kerr AM. Early clinical signs in the Rett disorder. Neuropediatrics. 1995;26:67–71.

Leonard H, Bower C. Is the girl with Rett syndrome normal at birth? Dev Med Child Neurol. 1998;40:115–21.

Marschik PB, Kaufmann WE, Sigafoos J, Wolin T, Zhang D, Bartl-Pokorny KD, et al. Changing the perspective on early development of Rett syndrome. Res Dev Disabil. 2013;34:1236–9.

Naidu S, Hyman S, Harris EL, Narayanan V, Johns D, Castora F. Rett syndrome studies of natural history and search for a genetic marker. Neuropediatrics. 1995;26:63–6.

Neul JL, Kaufmann WE, Glaze DG, Christodolou J, Clarke AJ, Bahi-Buisson N, et al. Rett syndrome: revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(6):944–50.

Einspieler C, Marschik PB. Regression in Rett syndrome: developmental pathways to its onset. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;98:320–32.

Zappella M. The Rett girls with preserved speech. Brain and Development. 1992;14(2):98–101.

Renieri A, Mari F, Mencarelli MA, Scala E, Ariani F, Longo I, et al. Diagnostic criteria for the Zappella variant of Rett syndrome (the preserved speech variant). Brain and Development. 2009;31(3):208–16.

Marschik PB, Einspieler C, Prechtl HF, Oberle A, Laccone F. Relabelling the preserved speech variant of Rett syndrome? Dev Med Child Neurol. 2010;52(2):218.

Marschik PB, Einspieler C, Oberle A, Laccone F, Prechtl HFR. Retracing atypical development: the preserved speech variant of Rett syndrome. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39:958–61.

Tarquinio DC, Hou W, Neul JL, Kaufmann WE, Glaze DG, Motil KJ, et al. The changing face of survival in Rett syndrome and MECP2-related disorders. Pediatr Neurol. 2015;53(5):402–11.

Urbanowicz A, Downs J, Girdler S, Ciccone N, Leonard H. Aspects of speech-language abilities are influenced by MECP2 mutation type in girls with Rett syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2015;167A(2):354–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajmg.a.36871.

Fehr S, Bebbington A, Ellaway C, Rowe P, Leonard H, Downs J. Altered attainment of developmental milestones influences the age of diagnosis of Rett syndrome. J Child Neurol. 2011;26(8):980–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/0883073811401396.

Marschik PB, Pini G, Bartl-Pokorny KD, Duckworth M, Gugatschka M, Vollmann R, et al. Early speech-language development in females with Rett syndrome: focusing on the preserved speech variant. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54(5):451–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2012.04123.x.

Einspieler C, Marschik PB, Domingues W, Talisa VB, Bartl-Pokorny KD, Wolin T, et al. Monozygotic twins with Rett syndrome: phenotyping the first two years of life. J Dev Phys Disabil. 2014;26(2):171–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10882-013-9351-3.

Marschik PB, Vollmann R, Bartl-Pokorny KD, Green VA, van der Meer L, Wolin T, et al. Developmental profile of speech-language and communicative functions in an individual with the preserved speech variant of Rett syndrome. Dev Neurorehabil. 2014;17(4):284–90.

Marschik PB, Einspieler C, Sigafoos J. Contributing to the early detection of Rett syndrome: the potential role of auditory gestalt perception. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33:461–6.

Pokorny FB, Bartl-Pokorny KD, Einspieler C, Zhang D, Vollmann R, Bölte S, et al. Typical vs, atypical: combining auditory gestalt perception and acoustic analysis of early vocalizations in Rett syndrome. Res Dev Disabil. 2018;82:109–19.

Hagerman RJ, Hagerman PJ. Fragile X syndrome: diagnosis, treatment, and research. 3rd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 2002.

Bagni C, Tassone F, Neri G, Hagerman R. Fragile X syndrome: causes, diagnosis, mechanisms, and therapeutics. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(12):4314–22.

Hunter J, Rivero-Arias O, Angelov A, Kim E, Fotheringham I, Leal J. Epidemiology of fragile X syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Med Genet. 2014;164(7):1648–58.

Rajaratnam A, Shergill J, Salcedo-Arellano M, Saldarriaga W, Duan X, Hagerman R. Fragile X syndrome and fragile X-associated disorders. F1000Res. 2017;6:2112. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.11885.1.

Hagerman RJ, Berry-Kravis E, Hazlett HC, Bailey DB Jr, Moine H, Kooy RF, et al. Fragile X syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17065. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2017.65.

Verkerk AJ, Pieretti M, Sutcliffe JS, Fu YH, Kuhl DP, Pizzuti A, et al. Identification of a gene (FMR-1) containing a CGG repeat coincident with a breakpoint cluster region exhibiting length variation in fragile X syndrome. Cell. 1991;65(5):905–14.

Bailey DBJ, Raspa M, Bishop E, Holiday D. No change in the age of diagnosis for fragile x syndrome: findings from a national parent survey. Pediatrics. 2009;124(2):527–33.

• Belardi K, Watson LR, Faldowski RA, Hazlett H, Crais E, Baranek GT, et al. A retrospective video analysis of canonical babbling and volubility in infants with fragile X syndrome at 9-12 months of age. J Autism Dev Disord. 2017;47(4):1193–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3033-4. Compares canonical babbling ratios of infants with fragile X syndrome and infants with typical development.

Marschik PB, Bartl-Pokorny KD, Sigafoos J, Urlesberger L, Pokorny FB, Didden R, et al. Development of socio-communicative skills in 9- to 12-month-old individuals with fragile X syndrome. Res Dev Disabil. 2014;35(3):597–602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2014.01.004.

Ozonoff S, Iosif A-M, Young GS, Hepburn S, Thompson M, Colombi C, et al. Onset patterns in autism: correspondence between home video and parent report. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;50(8):796–806.e1.

Palomo R, Ozonoff S. Autism and family home movies: a comprehensive review. Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27(2):S59–68.

Pokorny FB, Marschik PB, Einspieler C, Schuller BW. Does she speak RTT? Towards an earlier identification of Rett syndrome through intelligent pre-linguistic vocalisation analysis. Proc Interspeech. 2016:1953–7.

Orlandi S, Manfredi C, Bocchi L, Scattoni M. Automatic newborn cry analysis: a non-invasive tool to help autism early diagnosis. Proc EMBC. 2012:2953–6.

Xu D, Gilkerson J, Richards J, Yapanel U, Gray S. Child vocalization composition as discriminant information for automatic autism detection. Proc EMBC. 2009:2518–22.

Oller DK, Niyogi P, Gray S, Richards JA, Gilkerson J, Xu D, et al. Automated vocal analysis of naturalistic recordings from children with autism, language delay, and typical development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(30):13354–9. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1003882107.

Schuller B. Intelligent audio analysis. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2013.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Austrian Science Fund (FWF). This study was supported by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF; P25241, TCS24), the Austrian National Bank (OeNB; P16430), and the Leibniz ScienceCampus Primate Cognition.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Dajie Zhang and Peter B. Marschik shared corresponding and senior author

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Communication Disorders

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lang, S., Bartl-Pokorny, K.D., Pokorny, F.B. et al. Canonical Babbling: A Marker for Earlier Identification of Late Detected Developmental Disorders?. Curr Dev Disord Rep 6, 111–118 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-019-00166-w

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40474-019-00166-w