Abstract

Purpose of Review

To provide standardized guidance for transplant programs to maximize financial reimbursement related to living donor care and to minimize financial consequences of evaluation, surgical, and follow-up care to living donor candidates and donors.

Recent Findings

In 2014, the American Society for Transplantation (AST) Live Donor Community of Practice (LDCOP) “Consensus Conference on Best Practices in Live Kidney Donation” identified inconsistencies in billing practices as a barrier to living donor financial neutrality and issued a strong recommendation that the transplant community actively pursue strategies and policies to make living donation a financially neutral act, within the framework of federal law. The LDCOP convened a multidisciplinary group of experts to review and synthesize current Medicare regulations and commercial payer practices related to billing for living donor care and the implications for transplant programs and patients. We developed guidance for transplant program staff related to strategies to: consistently and appropriately obtain reimbursement via the Medicare Cost Report by utilizing organ acquisition; coordinate available coverage for donor pretesting, evaluation, hospitalization, follow-up care, and complications; coordinate charges in kidney paired donation; and maximize coverage through private insurance contracting. We also offer recommendations to protect donor confidentiality in the context of billing and to educate and prepare donor candidates and donors about any remaining gaps in coverage related to donation.

Summary

Best practices in billing for living donation-related care should focus on balancing cost recovery, regulatory compliance, and minimized donor burden. Herein, we offer nine recommendations for best practice. We also offer a platform of seven recommendations for research and advocacy efforts to better understand the climate of living donor medical costs and to optimize billing practices that support provision of living donor transplant services to all patients who can benefit and to achieve financial neutrality for living donors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Living donor kidney transplantation (LDKT) is the best treatment for most patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD), conferring improved length and quality of life compared to dialysis or deceased donor transplantation, at lower costs to the healthcare system [1,2,3]. Of concern, living donation rates in the USA have declined or remained stagnant since the early 2000s, despite a variety of approaches to improve access (i.e., kidney paired donation (KPD), growth of non-directed living donation, and ABO-incompatible transplantation) [4].

In 2014, with the support of ten other organizations, the American Society for Transplantation (AST) Live Donor Community of Practice (LDCOP) convened a “Consensus Conference on Best Practices in Live Kidney Donation”, including 77 stakeholders representing all aspects of living donor care, to identify best practices in living donor care and knowledge gaps that might affect living donation or LDKT rates. This conference issued a strong consensus recommendation that the transplant community actively pursue strategies and policies to make living donation a financially neutral act, within the framework of federal law [5]. A definition of financial neutrality was later proposed to include coverage and/or reimbursement of all medical, travel, and lodging costs, along with lost wages, related to the act of donating an organ [6]. It is widely agreed that living donor candidates and living donors should not have to pay medical costs associated with living donor evaluation or care [5, 7,8,9].

However, living donor consensus conference attendees highlighted substantial variation in practice among transplant programs in terms of which predonation and postdonation medical costs are paid, how they are paid, and by whom [5, 8••, 10]. Such variation can in part be attributed to variable interpretation of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) regulations and can have a significant impact on expenses passed on to donors and donor candidates. As such, it was recommended that resources be developed to “provide uniform guidance to transplant programs in relation to billing options to maximize resources available to living kidney donors [about] Medicare Organ Acquisition Cost Report [and] Medicare Part B [and] private insurance [and] uniform guidance to payers on coverage for living donor care.” [8••] In April 2016, CMS offered some clarification about the utilization of the Medicare Cost Report (MCR) for living donor care, but there are few formal resources to help transplant program administrations and billing departments understand and implement the current rule with respect to donor billing. Later, publications aiming to define and achieve financial neutrality seconded the need for clarification of transplant program billing guidelines and practices [6].

Evidence across multiple studies demonstrates that living donors in the USA incur financial burdens during the donation process [11,12,13]. Up to 96% of donors have reported out-of-pocket costs with a range of $300–$8000. Costs associated with donor travel to the transplant program, unpaid time off from work during recovery, unforeseen medical costs, and incidentals have been described. In terms of medical expenses specifically, in one multicenter study, 41% of donors had healthcare costs averaging $566; 36% paid for medications averaging $77 [12]. Nearly one in four (24%) donor candidates in this same study had medical costs during the donor evaluation phase alone with an average of $190 in medical costs and $34 in medications [12]. In addition, the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network/United Network for Organ Sharing (OPTN/UNOS) living kidney donor registry data from July 2004 to July 2015 reported that 16% of living donors (with known health insurance status) lacked health insurance at the time of donation. Young adults (aged 18–34 years), men, people of color, the unemployed, single, those with less education, smokers, and those who were normotensive were more likely to lack health insurance [14]. Recent publications demonstrate that the decline in living donation has been more pronounced in lower income groups [15], leading some to posit that costs associated with donation serve as a barrier or a disincentive.

In 2017, the AST LDCOP convened a multidisciplinary workgroup of experts in transplant administration and living donation clinical care to provide guidance regarding billing practices for living donor care. Specifically, the workgroup considered ways for transplant programs to appropriately maximize recovery of costs incurred, adhere to rules and regulations of such cost recovery, limit charges to donors, provide appropriate education to donor candidates about any remaining gaps, and complement and extend the clarifications issued by CMS in April 2016 [23]. This manuscript is a work product of the AST’s LDCOP and has been endorsed by the AST Board of Directors.

Herein, we provide standardized guidance for transplant programs to maximize coverage for donation-related care and minimize financial consequences to donors and donor candidates, consistent with current regulations and commercial payor practices. We offer recommendations on how to (1) consistently and appropriately obtain reimbursement via the MCR by utilizing Organ Acquisition Cost Centers (OACC); (2) coordinate billing and payment for donor pretesting, evaluation, hospitalization, follow-up care, and complications; (3) coordinate charges in kidney paired donation; (4) maximize insurance contracting; (5) honor confidentiality; and (6) prepare living donor candidates for any remaining gaps in coverage. We believe that by implementing these recommendations, transplant program administrative practices will be streamlined, care-related expenses to donor candidates and donors will be reduced, and donor candidates will be better prepared for financial impacts of the donation process. We do so via nine specific recommendations for practice. We also suggest areas of research and advocacy to optimize billing practices to support provision of living donor transplant services as the preferred ESRD treatment option and to achieve financial neutrality for donors.

Clarification of Terms and Usage: Medicare Cost Report Reimbursement of Charges for Donor Care, Organ Acquisition Cost Center, and the Standard Acquisition Charge

Organ acquisition costs, including living kidney donor acquisition, represent those costs incurred by transplant programs related to living donation. Transplant programs are required to establish an OACC in which all costs for organ acquisition are recorded. These are the costs for all recipients, regardless of payor. The costs of all potential and actual living donors are aggregated in an OACC. Annually, hospitals capture these costs on the Worksheet D-4 of the MCR, along with the number of Medicare usable organs (organs provided to Medicare beneficiaries). Medicare reimburses the hospital for these costs, proportionate to the number of Medicare usable organs to total usable organs.

The CMS Provider Reimbursement Manual requires transplant programs to establish a Standard Acquisition Charge (SAC), which represents the average cost of obtaining a living donor organ per transplant recipient [16]. It should be emphasized that expenses associated with the evaluation of all donor candidates, not just those who donated, are recorded to the OACC and used in calculating the SAC. The SAC is included on the transplant recipient’s hospital claim for all payors. For recipients with other health insurance coverage, services provided to the living donor for the purposes of evaluation and donation are not directly billed to the recipient’s payor, but rather are aggregated into the SAC. The SAC is the mechanism to reimburse transplant programs to recover the organ acquisition costs related to living donation. However, it is important to note that not all aspects of donor care are covered via organ acquisition. Appropriate coverage mechanisms for costs for donor evaluation and surgery, by inpatient versus outpatient source, are summarized in Table 1.

All costs, both hospital and physician services (internal and external), for living donor evaluations are eligible as organ acquisition costs by the intended recipient’s transplant program. These costs are retained by the original recipient’s transplant program regardless of whether the living donor candidate donates to that original intended recipient, to another recipient identified through KPD, or does not donate at all. Table 2 provides examples of living donor services appropriately categorized as organ acquisition costs, and services that are not organ acquisition costs.

Recommendation #1: All transplant programs can utilize a SAC with all payors, to avoid additional financial liability and inconvenience to donors, and to reinforce recording all donor expenses to the OACC so as to maximize Medicare reimbursement to the transplant program.

Recommendation #2: All costs associated with living donor evaluation can be recorded as an organ acquisition cost on the MCR and aggregated within a SAC, or individually billed to recipient’s commercial insurance plans.

Coverage of Living Donor Evaluation

In April 2016, CMS clarified guidelines for including donor costs in the living donor OACC and explicitly described donor evaluations as included [16]. This coverage includes initial screenings for cross matching, blood typing, blood pressure monitoring, and hemoglobin A1C, and includes internal and external costs incurred by the donor hospital to determine a donor candidate’s suitability for donation. This would also include all OPTN/UNOS requirements for living kidney donor evaluation, as long as the test or service determines suitability for donation [17].

There are differing interpretations regarding recording cancer screenings as these are normal adult health maintenance, and as such not unique to the donor evaluation. The transplant program should be consistent in either billing these to the donor’s insurance or recording prior to the OACC, and in informing donor candidates of this practice at the initial visit. Similarly, any diagnostic testing or treatment related to an abnormality discovered during the evaluation should be billed to the donor’s insurance. This can be somewhat ambiguous if the abnormality would not usually be pursued if the individual were not considering donation but becomes important in determining the donor’s risk or suitability. In general, all tests required solely to determine a living donor’s medical suitability and that would not be required otherwise can be recorded as an organ acquisition cost on the MCR and aggregated within a SAC or individually billed to the recipient’s commercial insurance plan.

Commercial/private payors (insurance companies) vary substantially in coverage practices for living donor evaluations. Differences can exist between insurance payors and between transplant program agreements with the same payors. Commercial payors may only provide coverage if initial testing is completed at healthcare facilities considered ‘in network’ or by the transplant program itself.

Transplant program practices may also vary regarding:

-

How much donor testing to complete at another facility and how early in the evaluation process.

-

The number of potential donor candidates the transplant program will evaluate simultaneously.

-

Whether or not to complete Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) testing, also known as tissue typing, prior to in-person donor evaluation.

Coverage of Living Donor Evaluation Components at Outside Facilities

The 2014 “Consensus Conference on Best Practices in Live Kidney Donation” recommended that referring nephrologists and primary care physicians should participate to improve efficiencies in the donor evaluation and selection process [18]. Though this may be ideal, we acknowledge that coordinating donor testing with outside facilities and providers, and arranging payment for related costs to outside facilities, can be logistically complicated. Transplant program practice may vary on the degree to which predonation testing can be coordinated with an outside facility, such as another transplant program.

Some transplant programs have systems and/or agreements in place to reimburse an outside facility at an agreed-upon rate, such as the local Medicare rate, and then add these expenses to their organ acquisition costs for reimbursement through their MCR [19]. For example, some transplant programs contract with outside companies (such as lab services or home health agencies) to facilitate blood-work and/or blood pressure monitoring elsewhere. Whatever payment agreement is determined, it is essential that it be consistent for external and internal facilities. For example, if a transplant program contracts with affiliated physicians to pay a discount on charges for professional fees related to evaluation, contractual agreements with outside physicians must be at that same rate [19].

Recommendation #3: For best practice, transplant programs can build partnerships with outside facilities, and potentially with one another, so as to reduce travel burdens for donor candidates early in the evaluation process [18].

Coverage of Living Donor Hospitalization

All hospital costs incurred during the admission for donation surgery, including perioperative care and complications prior to discharge, are recorded to the OACC. Costs for CMS mandated consults such as dietary, pharmacy, and social work are generally indirectly reimbursed as part of the hospital’s charge per day. If the consultant is employed by the transplant program directly, their salary can be included in the acquisition costs on the MCR. The CMS Provider Reimbursement Manual Publication 15-1 provides detailed instructions on using time studies to capture and document pretransplant salaries allowable for charge to the OACC [19•].

Once the donor is admitted to the hospital for the purposes of donation surgery, all professional fees are Part B expenses and billed directly to the recipient’s Medicare account. Commercial payors are usually directly billed, unless payment for donor professional services is included in a global payment for the transplant. Preoperative professional fees are covered by the global surgical fee in most cases as well.

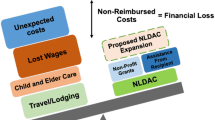

Coverage of Living Donation-Related Travel

Although coverage of donor travel costs is allowable under the National Organ Transplant Act NOTA [30], coverage via a payor is relatively rare. Some private payors may offer reimbursement for donor travel, up to a specified amount [10]. Medicare does not provide separate reimbursement for donor travel costs and these are not allowable as an organ acquisition cost on the MCR. If a donor or donor candidate will incur travel costs to get to the transplant program, resources such as the examples in Table 3 may be explored.

Recommendation #4: Transplant programs should prioritize service linkage to all avenues for donor travel cost reimbursement, including utilization of any available insurance benefits, and the National Living Donor Assistance Center (NLDAC).

Coverage for Living Donor Postoperative Care

Appropriate coverage mechanisms for costs of postdonation care, by inpatient versus outpatient source, are summarized in Table 4. Coverage of the costs for postoperative outpatient follow-up and any post discharge complications is more varied across transplant program practices.

-

Expenses incurred by the transplant program for routine, early postoperative follow-up care are included in the transplant program’s OACC. Follow-up services performed by the operating physician are included in the 90-day global payment for the surgery.

-

Follow-up services billed by a physician other than the operating physician for up to 3 months following donation surgery should be billed under the recipient’s health insurance claim number.

-

Follow-up services more than 3 months post donation are billed using the recipient’s health insurance claim number.

Coverage for Routine Postdonation Follow-up, as Mandated by OPTN/UNOS

Current OPTN/UNOS policy requires transplant programs to achieve specific thresholds for collection and timely reporting of clinical and laboratory follow-up data (now at thresholds of 80% for clinical data and 70% for laboratory data) at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years postdonation [20]. The policy was informed by a Joint Societies Work Group and community-wide public comment, which included debate over logistical and financial challenges for transplant programs and donors [21, 22].

In April 2016, CMS revised the Provider Reimbursement Manual to specifically exclude the costs of the OPTN/UNOS mandated routine donor follow-up at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years from organ acquisition and also to disallow billing these services to the recipient’s Medicare insurance [23]. Recovering the costs of mandated follow-up is complicated and likely varies by transplant program.

Currently, there is no formal mechanism to reimburse donors or programs for the costs of complying with this follow-up mandate. Practice variation across programs in terms of interpretation and use of the MCR, and in access to other resources, can dramatically impact costs passed on to donors [8••, 10]. Although donor follow-up and care may be appropriately performed by a primary care provider (PCP) for the convenience of the donor, this generally requires donors to use their own insurance (which may incur copayments). Thus, options for covering the costs of follow-up include:

-

1.

Billing the non-Medicare beneficiary recipient’s insurance. These costs can also be included in the fee that is charged to commercial payors if not explicitly excluded by contract.

-

2.

Covering the costs with institutional or charitable funds at the transplant program [24]. For example, the Yale Center for Living Organ Donors recently described their new integrated follow-up initiative which partners with their hospital to pay the costs of a complete metabolic panel and spot urine protein ($14 per donor) [25].

-

3.

Allowancing donor costs at the transplant program level and deeming them “uncollectable or un-reimbursable,” necessary expenses to comply with a regulatory mandate.

-

4.

Billing the donor or donor’s insurance (for service either at the program or with a PCP). Notably, even since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, approximately 9% of US living kidney donors lack health insurance [14]. As such, some donors may be paying full costs for this follow-up or simply not complying.

Coverage for Living Donor Complications

Unfortunately, there is wide variation in coverage of costs associated with treating living donor complications. Coverage depends on recipient payer plans, individual transplant program practices, and varying definitions of what constitutes a complication of living donation.

Medicare will cover donor complications for an unlimited period of time, even if the recipient has died [26]. This coverage is not by means of the MCR, but by a standard claim filing by the provider and/or the facility to Medicare Part A (hospital) and Part B (professional fees), as applicable. Living donor complications can be billed to the recipient’s Medicare plan, excluding Medicare Advantage plans, provided the recipient was enrolled in Medicare at time of transplant or enrolls within 1 year of the transplant admission.

In general, commercial/private payors will not pay costs for living donor complications outside of the perioperative period, though in rare circumstances, this coverage is written into a contract. Commercial/private payors (insurers) generally consider early complications as covered by the global or bundled payment. Fee-for-service plans may cover early perioperative complications.

If the recipient insurance plan lacks coverage for living donor complications, transplant program practice varies. Options include billing the recipient personally, billing the facility or transplant program (when services are provided outside of the transplant program), billing the donor’s insurance, or utilizing a charity fund.

Recommendation #5: Transplant programs should verify a coverage plan for living donor complications as part of the financial clearance process prior to living donation. Whatever the transplant program policy, it is imperative that the details of who will be responsible for paying the costs of any donor complications should be discussed and documented before the donation and transplant occur. Having the donor (and the recipient if he or she will be responsible) confirm their receipt and understanding of this information is strongly recommended.

Recommendation #6: Transplant programs should strongly encourage, or mandate, eligible recipients to obtain Medicare Parts A and B to ensure coverage for living donor complications.

Coverage for the Costs of Kidney Paired Donation and “Remote” Donation

When a living donor candidate and an original, intended recipient elect to participate in a KPD program, the costs of the initial living donor evaluation are retained by the original intended recipient’s transplant program, regardless of whether the living donor donates to the original intended recipient, a recipient in KPD, or does not donate at all. Just as with directed donation, the costs of all hospital and physician services for predonation/pretransplant living donor and recipient evaluations become organ acquisition costs and are included in the MCR of the recipient’s transplant program [23]. In a KPD program, once the donor candidate is matched with a recipient, any additional tests requested by the matched recipient’s transplant program but performed by the donor’s program are billed to the matched recipient’s transplant program (with charges reduced to cost) and included as organ acquisition costs on the MCR of the matched recipient’s transplant program. This is true regardless of whether or not an actual donation occurs.

“Remote” kidney donation allows someone who wishes to donate a kidney to an intended recipient in a distant city to do so without traveling to the transplant program in the distant city [27]. Just as with KPD, the predonation costs of all hospital and physician services for the living donor evaluation should be sent to the recipient’s transplant program and are included as acquisition costs on the MCR of the recipient’s program.

When a living donor program procures and transports a kidney to a recipient’s transplant program, the living donor programs bills the recipient’s transplant program for the costs associated with procuring, packaging, and transporting the kidney. The living donor program records these costs on its MCR as organ acquisition costs and offsets any payments received from the recipient’s transplant program against its organ acquisition costs. The recipient’s transplant program records as part of its organ acquisition costs the amounts billed by the donor recovery program for the costs associated with procuring, packaging, and transporting the organ as well as any additional testing performed and billed by the donor’s program.

When a living donor travels to the recipient’s transplant program for the surgery, the hospitalization costs are included on the MCR of the recipient’s transplant program.

Adult transplant programs that perform donor evaluations and procedures for children’s hospitals do so under contract and are not treated the same as KPD. The adult hospital generally bills either direct costs or a SAC to the children’s hospital which in turn bills the recipient via the cost report or SAC.

Considerations for Contracting with Commercial/Private Payors

As mentioned, commercial/private payors (insurance companies) vary substantially in coverage of costs related to living donor care. Transplant programs should review the contractual agreements to determine core elements with respect to living donation and LDKT (Fig. 1). Once transplant programs are informed of the structure and content of contracts, they may be able to work with their hospital’s contracting team as well as payors to negotiate contracts that include language and reimbursement for costs associated with living donor care that may not be presently covered.

Recommendation #7: Transplant programs should review contractual agreements to determine core elements with respect to living donation and LDKT, as well as the possibility of including language specific to the reimbursement of claims for living donor care.

Confidentiality and Living Donor Service Billing

Transplant program personnel are often confused and concerned about the breach of confidentiality that might occur with sharing living donor information in the billing process. The primary reason why transplant programs need to establish a process for accessing and sharing donor information with respect to billing and claims payment is to comply with Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) hospital policy about confidentiality obligations.

There are distinct differences in sharing information in deceased donation compared to living donation. Living donors are capable of making their own decisions regarding how much information they are willing to share with recipients and these disclosures are protected under HIPAA. Although in some cases, the identities of living donors and recipients are known to one another, the details of protected health information (PHI) remain protected under HIPAA [16, 28].

Transplant programs should create a system with their facility’s admissions and billing staff to remove PHI from living donor bills prior to sending them to a third-party.

Recommendation #8: Establish a process to protect living donor confidentiality in billing practices.

The following are examples of systems and processes that may protect living donor confidentiality in billing practices:

-

1.

Creating a special insurance plan code to prevent automatic third-party billing.

-

2.

Automating an electronic process to remove donor demographic information from the claim prior to its submission.

-

3.

Developing a manual process to review all donor claims prior to submission.

-

4.

Using of a SAC, which eliminates the need to identify the specific donor.

Education of Living Donor Candidates About Financial Risks

The potential for living donor candidates and donors to incur costs associated with living donation varies widely according to individual transplant program billing practices, insurance contracts, and payor mix. It is therefore vital that living donor candidates be informed at the outset of any potential for financial liability associated with living donor medical care. It is recommended that transplant programs explicitly educate living donor candidates about their coverage (under the intended recipient’s insurance) and the program-specific billing practices in the event of rejected claims or coverage denial. Education about living donor financial risks should describe:

-

1.

Coverage provided by the recipient’s payor.

-

2.

Transplant program policy about whether to proceed with donation in the absence of sufficient coverage for the living donor (such as when an intended recipient declines to get Medicare Part B).

-

3.

Any coverage gaps, program-specific billing practices, and what this might mean for liability.

-

4.

The fact that living donor billing practices may vary by transplant program.

Recommendation #9: Inform living donor candidates in writing about their coverage (under the intended recipient’s insurance) and the individual transplant program’s billing practices.

Discussion and Recommendations

The practice of LDKT incurs complex financial considerations for transplant programs. Transplant programs must consistently and appropriately obtain reimbursement via the MCR by utilizing organ acquisition; coordinating available coverage for donor pretesting, evaluation, hospitalization, follow-up care, and complications; coordinate charges in KDP; maximize coverage through private insurance contracting; protect donor confidentiality; and fully educate donor candidates about the potential financial risks of donation. The guidance offered in this report is intended to help streamline transplant program administrative practices and to reduce care-related expenses incurred by donor candidates and donors.

We also offer platforms for advocacy and for research (Fig. 2). Future research initiatives to improve the evidence base for best practices could include surveys of transplant programs on actual billing practices across phases of donor care and payor types, and add granularity regarding regional differences in donor billing practices. In addition, research on donor outcomes should include information on medical costs, particularly costs in the case of catastrophic complications.

Advancing billing for living donor care: best practices, advocacy goals, and future research needs. CTC Certified Transplant Center, MCR Medicare Cost Report, NLDAC National Living Donor Assistance Center, OACC Organ Acquisition Cost Center, OPTN/UNOS Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/United Network for Organ Sharing, SAC Standard Acquisition Charge

With regard to policy, we advocate that guidance be issued to encourage insurance contracts covering transplantation services to comprehensively reimburse the costs of living donor care, including the costs of evaluation and complications. Notably, in other disease states, laws have been passed to mandate adequate insurance coverage for necessary care (e.g., mental health parity in the Affordable Care Act; laws about dialysis staffing ratios or erythropoietin coverage) [26, 29].

In the current system, coverage gaps for living donor aftercare and complications are particularly problematic. If the transplant community is to take the goal of living donor financial neutrality seriously, it must build better systems to protect living donors in this devastating, if rare, circumstance. Although complications in the immediate postoperative period are easily identified and typically covered, there is less consensus about treatment of conditions such as new onset hypertension, postoperative depression, or a keloid scar reported 6 months postdonation. Recent publications have recommended continued discussion and establishment of a neutral body to review claims [6]. Developing mechanisms to reimburse the costs of mandated postdonation follow-up is a priority. Development of training criteria for a ‘living donor financial coordinator’ role may help ensure that transplant program staff have the knowledge and skills to optimize billing for donation services. Prioritizing use of best practices for financially efficient practice, transparency, and minimized financial risk for donors is a vital way to support opportunities for healthy, willing persons to give the gift of life. Furthermore, ongoing research and advocacy efforts related to optimizing billing practices should be prioritized.

Abbreviations

- AST:

-

American Society for Transplantation

- CMS:

-

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

- CTC:

-

Certified Transplant Center

- ESRD:

-

End-Stage Renal Disease

- HIPAA:

-

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

- HLA:

-

Human Leukocyte Antigen

- HRSA:

-

Health Resources and Services Administration

- KPD:

-

Kidney Paired Donation

- LDKT:

-

Living Donor Kidney Transplant

- LDCOP:

-

Live Donor Community of Practice

- MCR:

-

Medicare Cost Report

- NLDAC:

-

National Living Donor Assistance Center

- NOTA:

-

National Organ Transplant Act

- OACC:

-

Organ Acquisition Cost Center

- OPTN/UNOS:

-

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network/ United Network for Organ Sharing

- PCP:

-

Primary Care Provider

- PHI:

-

Protected Health Information

- SAC:

-

Standard Acquisition Charge

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

U. S. renal data system. USRDS 2015 annual data report: end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the United States. Ch 7: transplantation. Available at: https://www.usrds.org/2016/view/v2_07.aspx (accessed: December 10, 2018). Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; 2016.

Axelrod DA, Schnitzler MA, Xiao H, Irish W, Tuttle-Newhall E, Chang SH, et al. An economic assessment of contemporary kidney transplant practice. Am J Transplant. 2018;18:1168–76.

Schnitzler MA, Skeans MA, Axelrod DA, Lentine KL, Randall HB, Snyder JJ, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2016 Annual Data Report: Economics. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(Suppl 1):464–503.

Hart A, Smith JM, Skeans MA, Gustafson SK, Wilk AR, Robinson A, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2016 annual data report: kidney. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(Suppl 1):18–113.

LaPointe Rudow D, Hays R, Baliga P, Cohen DJ, Cooper M, Danovitch GM, et al. Consensus conference on best practices in live kidney donation: recommendations to optimize education, access, and care. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:914–22.

Hays R, Rodrigue JR, Cohen D, Danovitch G, Matas A, Schold J, et al. Financial neutrality for living organ donors: reasoning, rationale, definitions, and implementation strategies. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:1973–81.

Leichtman A, Abecassis M, Barr M, Charlton M, Cohen D, Confer D, et al. Living kidney donor follow-up: state-of-the-art and future directions, conference summary and recommendations. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2561–8.

•• Tushla L, Rudow DL, Milton J, Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Hays R. Living-donor kidney transplantation: reducing financial barriers to live kidney donation--recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1696–702 This report by the Living Donation Financial Barriers Workgroup of the 2014 AST ‘Live Donor Consensus Conference’ assessed the financial impact of living kidney donation, analyzed employment and insurance factors, evaluated international models for addressing direct and indirect costs faced by living donors, and summarized current available resources. The workgroup issued a series of recommendations, which include the provision of standardized, vetted education to providers about options to maximize donor coverage and minimize financial effect to donors within the current climate.].

Delmonico FL, Martin D, Dominguez-Gil B, Muller E, Jha V, Levin A, et al. Living and deceased organ donation should be financially neutral acts. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:1187–91.

Lapointe Rudow D, Cohen D. Practical approaches to mitigating economic barriers to living kidney donation for patients and programs. Curr Transpl Rep. 2017;4:24–31.

Klarenbach S, Gill JS, Knoll G, Caulfield T, Boudville N, Prasad GV, et al. Economic consequences incurred by living kidney donors: a Canadian multi-center prospective study. Am J Transplant. 2014;14:916–22.

Rodrigue JR, Schold JD, Morrissey P, Whiting J, Vella J, Kayler LK, et al. Indirect costs following living kidney donation: findings from the KDOC study. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:869–76.

Wiseman JF, Jacobs CL, Larson DB, Berglund DM, Garvey CA, Ibrahim HN, et al. Financial burden borne by laparoscopic living kidney donors. Transplantation. 2017;101:2253–7.

Rodrigue JR, Fleishman A. Health insurance trends in United States living kidney donors (2004 to 2015). Am J Transplant. 2016;16:3504–11.

Gill J, Joffres Y, Rose C, Lesage J, Landsberg D, Kadatz M, et al. The change in living kidney donation in women and men in the United States (2005-2015): a population-based analysis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2018;29:1301–8.

Department of Health and Human Services. Uses and disclosures for treatment, payment, and health care operations. 45 CFR 164.506. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/privacy/guidance/disclosures-treatment-payment-health-care-operations/index.html. (Accessed: Decebmer 10, 2018).

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN)/United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). OPTN Policies, Policy 14: Living Donation. Available at: http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/governance/policies/ (Accessed: December 10, 2018).

Moore DR, Serur D, Rudow DL, Rodrigue JR, Hays R, Cooper M. American Society of T. Living donor kidney transplantation: improving efficiencies in live kidney donor evaluation--recommendations from a consensus conference. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10:1678–86.

• Center for Medicare & Medicaid Studies . Provider Reimbursement Manual (PRM). CMS Pub. 15–1, Chapter 31: Section 3106. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Manuals/Paper-Based-Manuals-Items/CMS021929.html (Accessed: December 10, 2018). This document clarifies and explains Medicare’s payment policy regarding organ acquisition costs and payment for live donation payment and kidney paired donation.

OPTN (Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network)/UNOS (United Network for Organ Sharing). OPTN Policies, Policy 18: Data Submission Requirements. http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/governance/policies/ (Accessed: December 10, 2018).

Waterman AD, Dew MA, Davis CL, McCabe M, Wainright JL, Forland CL, et al. Living-donor follow-up attitudes and practices in US kidney and liver donor programs. Transplantation. 2013;95:883–8.

Mandelbrot DA, Pavlakis M, Karp SJ, Johnson SR, Hanto DW, Rodrigue JR. Practices and barriers in long-term living kidney donor follow-up: a survey of US transplant centers. Transplantation. 2009;88:855–60.

Department of Health & Human Services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Provider Reimbursement Manual. Part 1, Chapter 31: Organ Acquisition Payment Policy. Transmittal 471; Date: April 1, 2016. Available at: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Guidance/Transmittals/downloads/R471pr1.pdf. Accessed: Decebmer 10, 2018.

Keshvani N, Feurer I, Rumbaugh E, Dreher A, Zavala E, Stanley M, et al. Evaluating the impact of performance improvement initiatives on transplant center reporting compliance and patient follow-up after living kidney donation. Am J Transplant. 2015;15:2126–35.

Kulkarni S, Thiessen C, Formica R, Schilsky M, Mulligan D, D'Aquila R. The long-term follow-up and support for living organ donors: a center-based initiative founded on developing a Community of Living Donors. Am J Transplant. 2016;16:3385–91.

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Essential Health Benefits, Actuarial Value and Accreditation Standards, Final rule (describes components of mental health parity act). Available at: https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Files/Downloads/ehb-av-accred-final-2-25-2013v2.pdf. (Accessed: December 10, 2018).

National Kidney Regsitry. Remote kidney donation: for living kidney donors who do not want to travel. Available at: https://www.kidneyregistry.org/info/remote-donation.php. Accessed: December 10, 2018.

Organ Procurement & Transplantation Network (OPTN). Guidance for Donor and Recipient Information Sharing. Available at: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/resources/guidance/guidance-for-donor-and-recipient-information-sharing/ (Accessed: December 10, 2018).

Texas Department of Health and Human Services. Laws and Rules - End-Stage Renal Disease Facilities Available at: https://dshs.texas.gov/facilities/esrd/laws-rules.aspx. (Accessed: December 10, 2018).

National Organ Transplant Act 1984 (1984 Pub.L. 98–507). Available at: https://history.nih.gov/research/downloads/PL98-507.pdf. (Accessed: December 10, 2018).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the AST Executive Committee, including the LDCOP past chair Didier Mandelbrot, MD, who helped form the workgroup, the AST Education Committee, and the AST Board of Directors for review and feedback.We also acknowledge the late Debbie Mast, from Stanford Healthcare, Palo Alto, CA, whose contribution to the foundational concepts of this article was of great significance.

Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by an award from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) No. R01-DK096008 (KLL). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDDK or the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors are volunteer members of the American Society of Transplantation Living Donor Community of Practice (LDCOP).

Rebecca Hays, MSW, APSW [2] consults for Novartis on living donation. The terms of this arrangement have been reviewed for objectivity in research and presentation.

Christie Thomas reports clinical trial support from Shire Viropharma, outside the submitted work.

Andrea Tietjen, Robert Howey, Krista Lentine, Gwen NcNatt, and Ursula Lebron-Banks declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Live Kidney Donation

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tietjen, A., Hays, R., McNatt, G. et al. Billing for Living Kidney Donor Care: Balancing Cost Recovery, Regulatory Compliance, and Minimized Donor Burden. Curr Transpl Rep 6, 155–166 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-019-00239-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-019-00239-0