Abstract

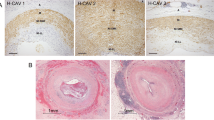

Cardiac allograft vasculopathy (CAV) is an immune and nonimmune-mediated process in which heart transplantation patients develop neointimal proliferative hyperplasia of the coronary arteries, typically starting distally and resulting in diffuse luminal narrowing. Risk factors include traditional coronary risk factors often resulting from side effects of immunosuppressive drugs, infection by cytomegalovirus and rejection, particularly antibody-mediated. Despite the advent of effective immunosuppression, CAV remains the primary cause of long-term mortality for heart transplant recipients. Patients undergo routine protocol surveillance for CAV after transplant, and various noninvasive and invasive diagnostic approaches can be employed in suspected CAV. Therapy is aimed primarily at prevention, given the incurable nature of CAV. The mainstay preventive therapies include statins and anti-proliferative immunosuppressive agents. In patients who develop CAV, treatment includes percutaneous coronary intervention and even retransplantation as CAV can result in irreversible systolic dysfunction and/or restrictive cardiomyopathy. This critical review aims to summarize our current knowledge of risk factors, diagnostic strategies, and therapy for CAV in heart transplant patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Wilhelm MJ. Long-term outcome following heart transplantation: current perspective. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(3):549.

Lund LH, Edwards LB, Kucheryavaya AY, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-first Official Adult Heart Transplant Report—2014; focus theme: Retransplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33(10):996–1008. A comprehensive report of 116,104 heart transplantations performed worldwide through June 30, 2013, including donor and recipient demographics and morbidity and mortality.

Cooper DK. Christiaan Barnard and his contributions to heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20(6):599–610.

Brink JG, Hassoulas J. The first human heart transplant and further advances in cardiac transplantation at Groote Schuur hospital and the university of cape town—with reference to: the operation. A human cardiac transplant: an interim report of a successful operation performed at Groote Schuur hospital, Cape Town. Cardiovasc J Afr. 2009;20(1):31–5.

Hunt SA, Haddad F. The changing face of heart transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(8):587–98.

Schmauss D, Weis M. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: recent developments. Circulation. 2008;117(16):2131–41.

Ramzy D, Rao V, Brahm J, Miriuka S. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: a review. Can J Surg. 2005;48(4):319.

Aranda Jr JM, Hill J. Cardiac transplant vasculopathy. CHEST J. 2000;118(6):1792–800.

Segovia J. Update on cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2002;7(3):240–51.

van Loosdregt J, van Oosterhout MF, Bruggink AH, et al. The chemokine and chemokine receptor profile of infiltrating cells in the wall of arteries with cardiac allograft vasculopathy is indicative of a memory T-helper 1 response. Circulation. 2006;114(15):1599–607.

Mehra MR, Crespo-Leiro MG, Dipchand A, et al. International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation working formulation of a standardized nomenclature for cardiac allograft vasculopathy—2010. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29(7):717–27.

Caforio AL, Tona F, Fortina AB, et al. Immune and nonimmune predictors of cardiac allograft vasculopathy onset and severity: Multivariate risk factor analysis and role of immunosuppression. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(6):962–70.

Tanaka M, Mokhtari GK, Terry RD, et al. Prolonged cold ischemia in rat cardiac allografts promotes ischemia–reperfusion injury and the development of graft coronary artery disease in a linear fashion. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24(11):1906–14.

Zhao ZQ, Nakamura M, Wang NP, et al. Reperfusion induces myocardial apoptotic cell death. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;45(3):651–60.

Weis M, von Scheidt W. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy: a review. Circulation. 1997;96(6):2069–77.

Lázaro IS, Bonet LA, López JM, et al. Influence of traditional cardiovascular risk factors in the recipient on the development of cardiac allograft vasculopathy after heart transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2008;40(9):3056–57.

Kobashigawa J. What is the optimal prophylaxis for treatment of cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2000;1(3):166–71.

Steinberg HO, Bayazeed B, Hook G, Johnson A, Cronin J, Baron AD. Endothelial dysfunction is associated with cholesterol levels in the high normal range in humans. Circulation. 1997;96(10):3287–93.

Davignon J, Ganz P. Role of endothelial dysfunction in atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2004;109(23 Suppl 1):III27–32.

Hadi HA, Carr CS, Suwaidi J. Endothelial dysfunction: cardiovascular risk factors, therapy, and outcome. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2005;1(3):183.

Delgado JF, Reyne AG, de Dios S, et al. Influence of cytomegalovirus infection in the development of cardiac allograft vasculopathy after heart transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;34(8):1112–9. This study demonstrated the relationship of CMV with CAV in a regression multivariate analysis of 166 heart transplant patients prospectively followed for CMV and CAV occurrence.

Valantine HA. The role of viruses in cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(2):169–77.

Grattan MT, Moreno-Cabral CE, Starnes VA, Oyer PE, Stinson EB, Shumway NE. Cytomegalovirus infection is associated with cardiac allograft rejection and atherosclerosis. JAMA. 1989;261(24):3561–6.

Valantine HA, Gao SZ, Menon SG, et al. Impact of prophylactic immediate posttransplant ganciclovir on development of transplant atherosclerosis: a post hoc analysis of a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Circulation. 1999;100(1):61–6.

Taylor DO, Edwards LB, Boucek MM, et al. Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Twenty-third Official Adult Heart Transplantation Report—2006. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25(8):869–79.

Costanzo MR, Naftel DC, Pritzker MR, et al. Heart transplant coronary artery disease detected by coronary angiography: a multiinstitutional study of preoperative donor and recipient risk factors. Cardiac transplant research database. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1998;17(8):744–53.

Johnson DE, Alderman EL, Schroeder JS, et al. Transplant coronary artery disease: histopathologic correlations with angiographic morphology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17(2):449–57.

Bangalore S, Bhatt DL. Coronary intravascular ultrasound. Circulation. 2013;127(25):e868–74.

St Goar FG, Pinto FJ, Alderman EL, et al. Intracoronary ultrasound in cardiac transplant recipients. In vivo evidence of “angiographically silent” intimal thickening. Circulation. 1992;85(3):979–87.

Tuzcu EM, Hobbs RE, Rincon G, et al. Occult and frequent transmission of atherosclerotic coronary disease with cardiac transplantation. Insights from intravascular ultrasound. Circulation. 1995;91(6):1706–13.

Spes CH, Klauss V, Rieber J, et al. Functional and morphological findings in heart transplant recipients with a normal coronary angiogram: an analysis by dobutamine stress echocardiography, intracoronary Doppler and intravascular ultrasound. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999;18(5):391–8.

Terashima M, Kaneda H, Suzuki T. The role of optical coherence tomography in coronary intervention. Korean J Intern Med. 2012;27(1):1–12.

Lowe HC, Narula J, Fujimoto JG, Jang I. Intracoronary optical diagnostics: current status, limitations, and potential. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2011;4(12):1257–70.

Gutierrez-Chico JL, Alegria-Barrero E, Teijeiro-Mestre R, et al. Optical coherence tomography: from research to practice. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;13(5):370–84.

Garrido IP, García-Lara J, Pinar E, et al. Optical coherence tomography and highly sensitivity troponin T for evaluating cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2012;110(5):655–61.

Khandhar SJ, Yamamoto H, Teuteberg JJ, et al. Optical coherence tomography for characterization of cardiac allograft vasculopathy after heart transplantation (OCTCAV study). J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(6):596–602.

Schubert S, Abdul-Khaliq H, Wellnhofer E, et al. Coronary flow reserve measurement detects transplant coronary artery disease in pediatric heart transplant patients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27(5):514–21.

Smart FW, Ballantyne CM, Cocanougher B, et al. Insensitivity of noninvasive tests to detect coronary artery vasculopathy after heart transplant. Am J Cardiol. 1991;67(4):243–7.

Pollack A, Nazif T, Mancini D, Weisz G. Detection and imaging of cardiac allograft vasculopathy. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(5):613–23. This JACC State-of-the-Art Paper provides a comprehensive review of existing and developing imaging modalities for the detection and surveillance of CAV.

Aranda Jr JM, Weston MW, Puleo JA, Fontanet HL. Effect of loading conditions on myocardial relaxation velocities determined by Doppler tissue imaging in heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1998;17(7):693–7.

Dandel M, Hummel M, Muller J, et al. Reliability of tissue Doppler wall motion monitoring after heart transplantation for replacement of invasive routine screenings by optimally timed cardiac biopsies and catheterizations. Circulation. 2001;104(12 Suppl 1):I184–91.

Miller CA, Chowdhary S, Ray SG, et al. Role of noninvasive imaging in the diagnosis of cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2011;4(5):583–93.

Pethig K, Heublein B, Kutschka I, Haverich A. Systemic inflammatory response in cardiac allograft vasculopathy: High-sensitive C-reactive protein is associated with progressive luminal obstruction. Circulation. 2000;102(19 Suppl 3):III233–6.

Labarrere CA, Lee JB, Nelson DR, Al-Hassani M, Miller SJ, Pitts DE. C-reactive protein, arterial endothelial activation, and development of transplant coronary artery disease: a prospective study. Lancet. 2002;360(9344):1462–7.

Labarrere CA, Nelson DR, Cox CJ, Pitts D, Kirlin P, Halbrook H. Cardiac-specific troponin I levels and risk of coronary artery disease and graft failure following heart transplantation. JAMA. 2000;284(4):457–64.

Labarrere CA, Pitts D, Nelson DR, Faulk WP. Vascular tissue plasminogen activator and the development of coronary artery disease in heart-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(17):1111–6.

Labarrere CA, Nelson DR, Faulk WP. Endothelial activation and development of coronary artery disease in transplanted human hearts. JAMA. 1997;278(14):1169–75.

Labarrere CA, Nelson DR, Faulk WP. Myocardial fibrin deposits in the first month after transplantation predict subsequent coronary artery disease and graft failure in cardiac allograft recipients. Am J Med. 1998;105(3):207–13.

Park MH, Scott RL, Uber PA, Harris BC, Chambers R, Mehra MR. Usefulness of B-type natriuretic peptide levels in predicting hemodynamic perturbations after heart transplantation despite preserved left ventricular systolic function. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90(12):1326–9.

Mehra MR, Uber PA, Walther D, et al. Gene expression profiles and B-type natriuretic peptide elevation in heart transplantation: more than a hemodynamic marker. Circulation. 2006;114(1 Suppl):I21–6.

Mehra MR, Uber PA, Potluri S, Ventura HO, Scott RL, Park MH. Usefulness of an elevated B-type natriuretic peptide to predict allograft failure, cardiac allograft vasculopathy, and survival after heart transplantation. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94(4):454–8.

Potena L, Grigioni F, Magnani G, et al. Prophylaxis versus preemptive anti-cytomegalovirus approach for prevention of allograft vasculopathy in heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28(5):461–7.

Corsini A, Raiteri M, Soma MR, Gabbiani G, Paoletti R. Simvastatin but not pravastatin has a direct inhibitory effect on rat and human myocyte proliferation. Clin Biochem. 1992;25(5):399–400.

Meiser BM, Wenke K, Thiery J, et al. Simvastatin decreases accelerated graft vessel disease after heart transplantation in an animal model. Transplant Proc. 1993;25(2):2077–9.

Kobashigawa JA, Katznelson S, Laks H, et al. Effect of pravastatin on outcomes after cardiac transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(10):621–7.

Kobashigawa JA, Moriguchi JD, Laks H, et al. Ten-year follow-up of a randomized trial of pravastatin in heart transplant patients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24(11):1736–40.

Wenke K, Meiser B, Thiery J, et al. Simvastatin initiated early after heart transplantation: 8-year prospective experience. Circulation. 2003;107(1):93–7.

Greenway SC, Butts R, Naftel DC, et al. Statin therapy is not associated with improved outcomes after heart transplantation in children and adolescents. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2015;35(4):457–65.

Mehra MR, Uber PA, Vivekananthan K, et al. Comparative beneficial effects of simvastatin and pravastatin on cardiac allograft rejection and survival. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40(9):1609–14.

Sanchez de Miguel L, De Frutos T, González-Fernández F, et al. Aspirin inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase expression and tumour necrosis factor-α release by cultured smooth muscle cells. Eur J Clin Invest. 1999;29(2):93–9.

Zhu J, Gao B. Simvastatin combined with aspirin increases the survival time of heart allograft by activating CD4 CD25 treg cells and enhancing vascular endothelial cell protection. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2015;24(3):173–8.

Fang JC, Kinlay S, Beltrame J, et al. Effect of vitamins C and E on progression of transplant-associated arteriosclerosis: a randomized trial. Lancet. 2002;359(9312):1108–13.

Mehra MR, Ventura HO, Smart FW, Stapleton DD. Impact of converting enzyme inhibitors and calcium entry blockers on cardiac allograft vasculopathy: from bench to bedside. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1995;14(6 Pt 2):S246–9.

Schroeder JS, Gao S, Alderman EL, et al. A preliminary study of diltiazem in the prevention of coronary artery disease in heart-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(3):164–70.

Carrier M, Rivard M, Kostuk W, et al. The Canadian study of cardiac transplantation. Atherosclerosis. Investigators of the CASCADE study. Can J Cardiol. 1999;15(12):1337–44.

Lijkwan MA, Cooke DT, Martens JM, et al. Cyclosporine treatment of high dose and long duration reduces the severity of graft coronary artery disease in rodent cardiac allografts. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2005;24(4):439–45.

Soukiasian HJ, Czer LS, Hai-Mei W, Luthringer D. Inhibition of graft coronary arteriosclerosis after heart transplantation. Am Surg. 2004;70(10):833.

Kobashigawa J, Miller L, Renlund D, et al. A randomized active-controlled trial of mycophenolate mofetil in heart transplant recipients1. Transplantation. 1998;66(4):507–15.

Kobashigawa J, Tobis J, Mentzer R, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil reduces intimal thickness by intravascular ultrasound after heart transplant: reanalysis of the multicenter trial. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(5p1):993–7.

Eisen HJ, Tuzcu EM, Dorent R, et al. Everolimus for the prevention of allograft rejection and vasculopathy in cardiac-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(9):847–58.

Keogh A, Richardson M, Ruygrok P, et al. Sirolimus in de novo heart transplant recipients reduces acute rejection and prevents coronary artery disease at 2 years: a randomized clinical trial. Circulation. 2004;110(17):2694–700.

Eisen H, Kobashigawa J, Starling R, et al. Everolimus versus mycophenolate mofetil in heart transplantation: a randomized, multicenter trial. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(5):1203–16. This landmark study in immunosuppressive therapy for heart transplantation demonstrated the advantages of mTOR inhibitor everolimus over mycophenolate mofetil, including reduction in CMV and CAV.

Kobashigawa JA, Pauly DF, Starling RC, et al. Cardiac allograft vasculopathy by intravascular ultrasound in heart transplant patients: Substudy from the everolimus versus mycophenolate mofetil randomized, multicenter trial. JACC Heart Fail. 2013;1(5):389–99.

Mancini D, Pinney S, Burkhoff D, et al. Use of rapamycin slows progression of cardiac transplantation vasculopathy. Circulation. 2003;108(1):48–53.

Andreassen A, Andersson B, Gustafsson F, et al. Everolimus initiation with early calcineurin inhibitor withdrawal in de novo heart transplant recipients: Three‐Year results from the randomized SCHEDULE study. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(4):1238–47.

Raichlin E, Bae JH, Khalpey Z, et al. Conversion to sirolimus as primary immunosuppression attenuates the progression of allograft vasculopathy after cardiac transplantation. Circulation. 2007;116(23):2726–33.

Jain SP, Ramee SR, White CJ, et al. Coronary stenting in cardiac allograft vasculopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;32(6):1636–40.

Zakliczynski M, Lekston A, Osuch M, et al. Comparison of long-term results of drug-eluting stent and bare metal stent implantation in heart transplant recipients with coronary artery disease. Transplant Proc. 2007;39(9):2859–61.

Beygui F, Varnous S, Montalescot G, et al. Long-term outcome after bare-metal or drug-eluting stenting for allograft coronary artery disease. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29(3):316–22.

Azarbal B, Arbit B, Ramaraj R, et al. Clinical and angiographic outcomes with everolimus eluting stents for the treatment of cardiac allograft vasculopathy. J Interv Cardiol. 2014;27(1):73–9.

Dasari TW, Saucedo JF, Krim S, et al. Clinical characteristics and in hospital outcomes of heart transplant recipients with allograft vasculopathy undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from the national cardiovascular data registry. Am Heart J. 2015;170(6):1086–91.

Agarwal S, Parashar A, Kapadia SR, et al. Long-term mortality after cardiac allograft vasculopathy: implications of percutaneous intervention. JACC Heart Fail. 2014;2(3):281–8.

Moss AJ, Hall WJ, Cannom DS, et al. Improved survival with an implanted defibrillator in patients with coronary disease at high risk for ventricular arrhythmia. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(26):1933–40.

Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, et al. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(12):877–83.

Bardy GH, Lee KL, Mark DB, et al. Amiodarone or an implantable cardioverter–defibrillator for congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(3):225–37.

Ptaszek LM, Wang PJ, Hunt SA, Valantine H, Perlroth M, Al-Ahmad A. Use of the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator in long-term survivors of orthotopic heart transplantation. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2(9):931–3.

Tsai VW, Cooper J, Garan H, et al. The efficacy of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in heart transplant recipients: Results from a multicenter registry. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2(3):197–201.

Goldraich L, Stehlik J, Kucheryavaya A, Edwards L, Ross H. Retransplant and medical therapy for cardiac allograft vasculopathy: International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Registry analysis. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(1):301–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Stuart Russell, Ike Okwuosa, and Nisha Gilotra declare no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Thoracic Transplantation

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gilotra, N.A., Okwuosa, I.S. & Russell, S.D. Cardiac Allograft Vasculopathy: What We Know in 2016. Curr Transpl Rep 3, 175–184 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-016-0105-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40472-016-0105-x