Abstract

Purpose of Review

The present study aimed to review the literature concerning the relationship between problematic online gaming (POG) and social anxiety, taking into account the variables implicated in this relationship. This review included studies published between 2010 and 2020 that were indexed in major databases with the following keywords: Internet gaming, disorder, addiction, problematic, social phobia, and social anxiety.

Recent Findings

In recent years, scientific interest in POG has grown dramatically. Within this prolific research field, difficulties associated with social anxiety have been increasingly explored in relation to POG. Indeed, evidence showed that individuals who experience social anxiety are more exposed to the risk of developing an excessive or addictive gaming behavior.

Summary

A total of 30 studies satisfied the initial inclusion criteria and were included in the present literature review. Several reviewed studies found a strong association between social anxiety and online gaming disorder. Furthermore, the relationships among social anxiety, POG, age, and psychosocial and comorbid factors were largely explored. Overall, the present review showed that socially anxious individuals might perceive online video games as safer social environments than face-to-face interactions, predisposing individuals to the POG. However, in a mutually reinforcing relationship, individuals with higher POG seem to show higher social anxiety. Therefore, despite online gaming might represent an activity able to alleviate psychopathological symptoms and/or negative emotional states, people might use online gaming to counterbalance distress or negative situations in everyday life, carrying out a maladaptive coping strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The social anxiety disorder (SAD), also known as social phobia, is an anxiety disorder characterized by fear in one or more social situations, leading to considerable distress, over-estimation of possible consequences of negative social evaluation, and impaired ability to face feared social situations [1, 2]. As several previous studies highlighted [3,4,5], socially anxious individuals might consider Internet as a safer social context than face-to-face interactions due to the lack of physical and auditory contacts, frequently developing a preference for online social interactions [6,7,8,9]. Later studies found that problematic Internet-related activities were strongly associated with individuals’ social anxiety, especially if younger [10,11,12,13,14]. Among the Internet-related activities, specific structural characteristics of gaming (such as design and narrative, achievements, online social interactions, and motivations) appeared particularly fascinating for individuals who attempt to escape the boredom of common life [15]. Indeed, videogames seem to help individuals to escape real life and reduce stress, problems, and isolation also through online social interactions [16,17,18,19]. In this regard, according to the compensatory Internet use model [20••], online videogames might offer other alternative virtual environments where highly socially anxious individuals transfer most of their social activities (such as the formation of strong friendships), alleviate their stressful life event-related negative feelings, and feel safer and more comfortable than in face-to-face socialization [21]. However, as Lo et al. [22] stated, online games reduce social anxiety only temporarily, dangerously reducing social experiences in face-to-face contexts [23]. Furthermore, several recent studies explored the association between problematic online gaming and social anxiety as well as depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and loneliness [24,25,26,27,28,29]. Indeed, despite online gaming might offer an alternative context in which individuals can reduce emotional distress, psychosocial problems, and isolation through online social interactions [16,17,18,19, 30], the excessive engagement in online gaming might represent a maladaptive coping strategy leading to negative outcomes [31,32,33].

Concerning the online gaming, in the last decade, it has been described as a social and not problematic activity for the majority of gamers [34] and concerns regarding the potential overpathologization of casual gamers have been raised [31, 33, 35, 36••, 37, 38••, 39, 40]. However, scientific research increasingly focused on problematic and potentially pathological Internet gaming [41,42,43]. In this regard, already in 2013, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) [44] provisionally included the Internet Gaming Disorder (IGD) in the Section III of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5), as condition that requires further research to be definitely included in the manual [44], adopting the substance use diagnostic criteria (i.e., preoccupation, withdrawal, tolerance) [45, 46]. Then, only more recently, the World Health Assembly officially declared Gaming Disorder (GD) as a diagnostic category to be included in the International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11) [47]. Nevertheless, a theoretical and methodological classification of the Internet gaming disorder is still lacking due to uncertainty in conceptualization, measurement, and clinical assessment [i.e., 35, 40, [48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58]. Furthermore, evidence suggested to address attention toward comorbidity factors associated with problematic gaming, since it may be present along with other pathologies [38••]. In addition to social anxiety, deficient self-regulation, negative mood, and affective disorders (e.g. anxiety and panic, distress, depression), psychosocial difficulties such as isolation, intense shyness, and consistent preference for online social interactions have been frequently associated with problematic online gaming [51, 59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67], especially among young individuals. Indeed, young people have been found typically engaged in high sensation-seeking and risky behaviors [68, 69] and they have been defined as a vulnerable population for problematic online gaming, with potential negative outcomes for their psychological, social, and physical health [61, 70].

In summary, in the past decade, the Internet gaming has dramatically grown becoming a widespread and often daily activity. However, individuals who experience social anxiety have been found more exposed to the risk of developing problematic online gaming because this online activity may help them to avoid and escape from difficulties and anxieties related to face-to-face social interactions [1, 71, 72]. A better understanding of the social anxiety-problematic online gaming relationship (and the possible related psychosocial difficulties) might provide several practical implications, especially considering the recent evidence about the association between social isolation and problematic gaming [73, 74]. Therefore, in light of this evidence, the present study aimed at reviewing the scientific studies published in the last ten years specifically focusing on the relation between problematic online gaming and social anxiety.

Materials and Methods

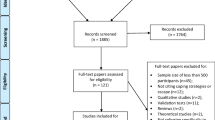

The review has been conducted using Web of Science, Scopus, and ScienceDirect as the main research databases, entering the following keywords: internet gaming* problematic* social anxiety*/ internet gaming* disorder* social anxiety*/ internet gaming* addict* social anxiety*/ internet gaming* problematic* social phobia*/ internet gaming* disorder* social phobia*/ internet gaming* addict* social phobia. The present literature review is in compliance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [75]. Progressive exclusion was performed by reading the abstract and, finally, the full text. The inclusion criteria for the present review were (i) studies containing quantitative empirical data, (ii) studies concerning Internet Gaming, (iii) studies published from 2010 to 2020, and (iv) studies providing a full-text article published in English. For comparison purposes, exclusion criteria were (i) studies focusing on the general Internet use, (ii) reviews, conference abstracts, letters, or editorials, and (iii) doctoral dissertations. Strong heterogeneity in reported studies’ findings and statistical information lead us to adopt a systematic narrative approach to report key outcomes.

Results

A total of 784 papers were initially identified. Subsequently, 754 papers that did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded. Thus, 30 studies that met the initial inclusion criteria were included in the present literature review (Fig. 1).

Different Perspectives on Problematic Online Gaming Research: Frameworks and Measures

Concerning the diagnostic instruments used to assess problematic video gaming (Table 1), several assessment tools based on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for IGD and focused on traditional online gaming addiction on desktop computers have been used. More specifically, two studies administered the Gaming Addiction Scale (GAS) [76,77,78] and two studies adapted the GAS for mobile gaming [79, 80]. Four studies used the Internet Gaming Disorder Scale (IGDS) [28, 72, 81,82,83] and Starcevic et al. [84] developed a semi-structured diagnostic interview consisting of nine items corresponding to the nine criteria for IGD. Moreover, Müller et al. [85] used the Scale for the Assessment of Internet and Computer game Addiction (AICA-S) [86] and Wei et al. [15] utilized the Chen’s Internet Addiction Scale (CIAS) [87]. Furthermore, Lopez-Fernandez et al. [88], Marino et al. [89], Severo et al. [90], and Wang and Cheng [91] tested the 9-item short form of IGDS (IGDS9-SF) [29]. Kircaburun et al. [92] used the 10-item Internet Gaming Disorder Test (IGDT-10) [93]. Finally, Van Rooij et al. [94] used the Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS) [95] to evaluate the adolescents’ online video game addiction, and later, other studies employed the Video game Addiction Test (VAT) [43, 96,97,98], a modified version of CIUS referred specifically to gaming.

Four studies adapted the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for substance dependence or pathological gambling to the online game addiction. In particular, according to previous studies [99], Hyun et al. [100] and Park et al. [101] employed 5 criteria: (i) online game playing for more than 4 h per day or 30 h per week; (ii) scores higher than 50 in the Internet Addiction Scale score [102]; (iii) irritability, anxiety, and aggressive behaviors when forced to stop online gaming; (iv) impaired behaviors or distress, economic problems, or maladaptive patterns of regular life due to excessive online gaming; and (v) altered diurnal rhythms and consequent outcomes in life patterns (i.e., online gaming at night and sleeping during the day, irregular meals, failure in personal hygiene, school truancy, or loss of job). Moreover, Karaca et al. [103] utilized the Computer Game Addiction Scale for Children (CGASC) [104]. Finally, following Gentile [105], Gentile et al. [106] evaluated the pathological video game use.

According to the cognitive behavioral model of problematic Internet use [6, 107, 108], Cole and Hooley [10] and Lee and Leeson [1] tested the Generalized Problematic Internet Use Scale (GPIUS) [107] on MMOs and MMORPGs players, respectively.

In an alternative conceptualization termed compensatory internet use, Kardefelt-Winther [20••, 109] problematized the common research methodology in studies on excessive internet use developing the Excessive Online Gaming Scale (EOGS) [109]. As well, Sheng and Wang [79] employed the EOGS.

Three studies developed ad hoc measures to explore gaming habits [110], game experience and game behaviors [71], and engagement and addiction to World of Warcraft [111, 112].

Measures of Social Phobia and Social Anxiety

Concerning the social phobia and social anxiety, the most employed self-report measure was the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) [15, 71, 83, 106, 110, 111, 113] and two studies used the SPIN short form (MINI SPIN) [85, 90, 114, 115] to evaluate the social phobic symptoms such as social situations fear, avoidance of social situations or performances, and physiological discomfort in social contexts. Marino et al. [89] used the Italian version of the Social Phobia Inventory (I-SPIN) [116]. Five studies used the Social Anxiety Scale for children (CSAS) [43, 80, 94, 97, 98, 117,118,119] aiming to explore how children deal with social avoidance and distress in new and known situations. Six studies [10, 72, 82, 84, 91, 109] utilized the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale and Social Phobia Scale measures (SIAS/SPS) or its short form [120, 121], and two companion scales aimed at measuring two related facets of social fears/anxiety. Furthermore, three studies utilized the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS) [1, 77, 78, 122] to assess social anxiety disorder and two Korean studies [100, 101] employed the Social Avoidance and Distress Scale (SADS) [123] to explore the fear of negative evaluation by others and the tendency to avoid social situations due to distress in the presence of others. Karaca et al. [103] and Sheng and Wang [79] used two different measures for children: the Social Anxiety Scale for Children (SASC) [124] and the Child Social Anxiety Scale [125], respectively. Finally, Kircaburun et al. [92] utilized the Social Anxiety Scale for adolescents short form (SAS-A) [126], Lopez-Fernandez et al. [88] the social phobia items of the Symptom Checklist-27-Plus (SCL-27-Plus) [127], and Khalil et al. [81] employed the Social Anxiety subscale of the MINI International Neuropsychiatry Interview for children and adolescents (MINI KID) [128].

Problematic Online Gaming and Social Anxiety

Several reviewed studies found a strong association between social anxiety and problematic online gaming [1, 15, 43, 71, 72, 77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85, 88,89,90, 94, 97, 98, 100, 101, 103, 106, 110, 111] among both young and adult individuals. More specifically, some studies highlighted significant differences between at-risk/problematic online gamers and no problematic/engaged video games users [43, 77, 81, 83, 85, 94, 100, 101, 111]. Indeed, problematic users, especially males [80], scored significantly higher in social anxiety compared with no problematic peers. Colder Carras et al. [97] used the latent class analysis to identify distinct classes of gamers (normative, problematic, at-risk, social at-risk, extensive, and social engaged gamers) and explored the association between social and non-social video gaming and social anxiety in both male and female adolescents. Interestingly, they found that while male social gamers had no significant associations with social anxiety, females’ engagement in social games reduced social anxiety, whereas non-social at-risk and extensive male gamers reported high social anxiety. Recently, Starcevic et al. [84] compared IGD patient group and general gamer group highlighting that patient group reported significantly higher social anxiety compared to general gamers. Finally, findings suggested that individuals with high level of social phobia spent more hours and played online video games during the weekends more than participants with lower social phobia [15].

Some correlational studies reported significant positive co-occurrence between social anxiety and problematic online gaming [79, 81, 82, 90, 98]. Kardefelt-Winther [109] suggested that social anxiety might be correlated with problematic video game use and that excessive use might be more usefully framed and considered as a coping strategy instead of as a compulsive behavior. Accordingly, Wei et al. [15] stated that socially anxious individuals might use games as an escape mechanism, avoiding face-to-face contact but significantly increasing online relationships.

Several studies explored the predictive effect of social anxiety on problematic online gaming, highlighting that gamers affected by social phobic symptoms were more prone to be engaged in virtual reality of online games, likely to avoid face-to-face social distress [1, 15, 72, 78, 88, 89]. Accordingly, Cole and Hooley [10] identified trait anxiety and social phobia as best predictors of problematic Internet use among online gamers, suggesting that generally anxious individuals who have difficulties in social situations are the people most likely to have problems online gaming. Similarly, Karaca et al. [103] reported that high social anxiety was a pivotal risk factor for both problematic gaming and online gaming addiction. On the contrary, only Kircaburun et al. [92] failed to identify social anxiety as a risk factor for IGD.

Inversely, two studies tested the predictive role of problematic online gaming on social anxiety [80, 106]. In a longitudinal growth model, Gentile et al. [106] found that the weekly amount of video game play significantly predicted the number of pathological gaming symptoms and that children who began with more pathological gaming symptoms demonstrated higher levels of social phobia. Similarly, the recent Wang et al.’s [80] findings reported that males addicted to mobile games tended to suffer more social anxiety. In addition, Wang and Cheng [91] found that gaming disorder measure did not explain a significant proportion of social anxiety. In a study focused on the MMORPG World of Warcraft (WoW), Martončik and Lokša [71] found that WoW players experienced less social anxiety in online world, especially in presence of and playing with known people. Similarly, Sauter et al. [110] found that individuals who played with known friends were less susceptible toward social anxiety. In Kardefelt-Winther’s [109] study, social anxiety did not predict WoW-related negative outcomes.

Problematic Online Gaming, Social Anxiety, and the Associated Factors

Three main orders of factors have been found to be associated with problematic online gaming and social anxiety: online gaming-related variables, psychosocial factors, and comorbid symptoms.

Concerning the online gaming-related variables, some studies reported a significant relationship between problematic online gaming and time spent video gaming [1, 43, 79, 82, 94, 103]. More specifically, findings stated that an increase in young individuals’ online gaming time raised the risk of addiction [90, 103], which in turn might gradually increase the time spent on video gaming [103]. On the contrary, according to Kardefelt-Winther [109], Lee and Leeson [1] showed that time spent playing was not indicative of problematic MMORPG usage. Other studies explored the motivations for online gaming using the Online Game Motivation Scale [129]. In this regard, assuming a compensatory view on MMO play, Kardefelt-Winther [109] evaluated the predictive effect of escapism, achievement, and social interactions motives underlying WoW-related negative outcomes and found that only escapism and achievement had significant effect. Furthermore, entering motivations in the regression model, the social anxiety lost the significant predictive effect on negative outcomes related to WoW play. Lehenbauer-Baum et al. [111] compared addicted and engaged players and showed that addicted gamers displayed higher achievement and immersion scores than engaged gamers. In a recent study focused on female gamers [88], the achievement and social motivations were detected as unique predictors of IGD, as well as strictly related to the identification with the avatar when playing videogames. Furthermore, Marino et al. [89] highlighted that social anxiety was directly associated with four escape, coping, fantasy, and recreation motives, but only escapism mediated the relationship between social anxiety and IGD. Finally, Sioni et al. [72] found that higher level of social phobia promoted stronger identification with gamers’ own avatar, which in turn exacerbated IGD symptoms.

The second order of factors refers to the psychosocial factors, including personality characteristics as well as social and family variables. More specifically, among the internal and personality factors, loneliness has been frequently explored [43, 71, 79, 80, 92, 94, 98, 109]. A strong association between loneliness, social anxiety, and problematic online gaming has been confirmed [43, 79, 80, 94, 98, 109]. Kardefelt-Winther [109] and Kircaburun et al. [92] failed to identify the predictive effect of loneliness on problematic online gaming, whereas this latter emerged as a pivotal predictive factor of loneliness in the Wang et al.’s [80] study. Martončik and Lokša [71] indicated that online gamers might experience less loneliness and social discomfort in virtual contexts. Other several psychosocial factors have been explored, such as perceived quality of life and life satisfaction [77, 83, 98, 110, 111], loneliness, stress [109], impulsivity [100, 101, 106], metacognitions [89], self-esteem [43, 92, 94, 98, 100, 101], the true self [1], and personality traits [10, 111]. Among the social variables, perceived social support [1], friendship quality [97], and social competence and skills [106] have been explored. Furthermore, the quality of parent–child relationship has been considered [100, 101, 106]. Also, cognitive factors have been explored [100, 101].

Finally, concerning the comorbid symptoms, the association among depression, anxiety, social anxiety, and problematic online gaming has been the most explored [10, 15, 43, 77,78,79,80,81,82, 84, 85, 88, 90,91,92, 94, 97, 98, 100, 101, 106, 110, 111]. In particular, depression symptoms as well as social anxiety have been found positively co-occurred with problematic online gaming [15, 79, 82] and problematic or addicted online gamers showed higher level of depression than engaged or non-problematic gamers [43, 85, 90, 94, 111], especially female gamers [77] and arcades games, sports online games, and casual games players [101]. Furthermore, depression has been reported also as a pivotal risk and predictive factor of problematic online gaming [15, 78, 92, 97, 98, 100], whereas, inversely, Gentile et al. [106] and Wang et al. [80] found that young individuals who became pathological gamers ended up with increased levels of depression, anxiety, loneliness, and social phobia. Wang and Cheng [91] found that gaming disorder measure did not explain a significant proportion of depression. Finally, only in two studies [84, 88], the depressive symptoms did not emerge as a predictor of problematic online gaming. According to Gentile et al. [106], also Müller et al. [85] found a strict relationship between problematic online gaming and anxiety and other studies showed the predictive role of anxious symptoms on problematic online gaming [10, 100]. Only Starcevic et al. [84] did not found confirmed this predictive role and Sauter et al. [110] found that gaming habits significantly predicted generalized anxiety but with negligible practical relevance. Finally, other studies explored comorbid symptoms including obsessive–compulsive disorder [84], ADHD [84, 100, 101], sleep quality and suicidal ideation [90], psychoactive substance use [43], Internet addiction [81, 84], problematic social media use [81, 89], and mobile phone addiction [79].

Problematic Online Gaming and Social Anxiety at Different Ages

Among the reviewed studies, some age-related differences emerged in the relationship between social anxiety and problematic online gaming, showing mixed findings. Only two studies focused on children’s problematic online gaming [103, 106]. More specifically, Karaka et al. [103] identified older age as a risk factor for online gaming addiction and Gentile et al. [106] confirmed that children with lower social competence and greater impulsivity showed increased pathological gaming symptoms, which in turn, over time, lead to higher levels of depression, anxiety, and social phobia. Several studies focused on adolescent samples. Phan et al. [77] highlighted that the incidence of IGD symptoms was similar before and after the age of 15 among both male and female adolescents, whereas Khalil et al. [81] found that gaming addicted adolescents had statistically significantly higher age and male sex. Other studies did not discuss their findings according to the adolescent age [43, 80, 94, 97, 98]. Six studies involved samples composed by adolescents and young adults. More specifically, Müller et al. [85] found that late adolescents sought treatment for online gaming more than for other Internet-based activities, whereas Kircaburun et al. [92], Severo et al. [90], and Wei et al. [15] reported that age was not significantly associated with Internet Gaming Disorder. Differently, Sheng and Wang [79] and Starcevic et al. [84] did not discuss the role of age in the problematic online gaming. Furthermore, some studies focused their research on emerging adult samples [10, 88, 101], but only two studies discussed their findings according to age, showing that there were no differences between problematic and non-problematic online gamers [10] and among different kind of games players, respectively [101]. Seven studies involved young adult and adult participants. Vanzoelen and Caltabiano [78] found that, as age increased, levels of social anxiety, behavioral inhibition, depression, and gaming addiction decreased, Sigerson et al. [82] tested and confirmed the strict measurement invariance of IGD scale for age, whereas in Sioni et al.’s study [72], age was not a significant factor. Similarly, Marino et al. [89] highlighted that age was not significantly associated with IGD. Lee and Leeson [1], Sauter et al. [110], and Wang and Cheng [91] did not explore age-based differences in association with problematic online gaming. Finally, other studies focused on a large range of age, including adolescents, young adults, and adults. In particular, despite findings did not highlight significant age-related differences between problematic and non-problematic gamers [100, 111] and 109 found that age was not significantly associated with online gaming-related negative outcomes, Subramaniam et al. [83] reported that increasing age was a significant risk factor for IGD. Martončik and Lokša [71] did not discuss their findings according to age.

Discussion

The present study reviewed the scientific literature published in the last ten years exploring the relationship between problematic online gaming, social anxiety, and other variables potentially implicated in this relationship. First, a large number of conceptual, theoretical, and/or methodological mixed approaches about problematic online gaming have been confirmed, thus showing the heterogeneity of conceptual and psychometric properties of the assessment tools largely used to measure problematic online gaming. According to recent findings by King et al. [38••], the IGD criteria have been found as privileged by the largest part of the studies [15, 72, 77,78,79,80, 82,83,84,85, 88, 90, 92, 100, 101, 103, 106], but other studies assumed different perspectives [1, 10, 43, 60, 71, 79, 94, 97, 98, 109, 111]. Concerning the frequency of use of online games, despite several reviewed studies reported a significant relationship between problematic online gaming and time spent video gaming [1, 43, 79, 82, 90, 94, 103], according to Kardefelt-Winther [109] and Lee and Leeson [1], the playing time variable should be used as a screening, rather than a diagnostic tool. Furthermore, mixed findings emerged concerning the relationship between age and problematic online gaming. As previous studies highlighted [49, 70, 78, 130, 131], the problematic online gaming has been found consistently associated with gamers’ younger age. On the contrary, among the reviewed studies, several studies found no significant age-related differences among problematic online (and offline) gamers [10, 15, 77, 82, 90, 92, 100, 101, 109, 111] and other studies showed that, as age increased, levels of problematic online gaming also increased [83, 85, 103]. Likely, according to Kardefelt-Winther [109], online gaming is increasingly becoming common across the age groups, and therefore also the correlated risks. Further research on this issue is needed.

Overall, despite the several different frameworks concerning the problematic online gaming, the association between problematic online gaming and social anxiety has been largely confirmed [1, 15, 43, 71, 72, 77,78,79,80, 82,83,84,85, 88, 90, 94, 97, 98, 100, 101, 103, 106, 111].

Previous research suggested that socially anxious individuals might perceive the Internet as a safer social environment than face-to-face interactions [3,4,5,6, 8], often developing a preference for online socialization [9, 132,133,134,135]. Subsequently, this psychosocial vulnerability [108] might predispose individuals to the online gaming. In this regard, the literature of the last ten years largely showed that individuals with a serious tendency for problematic or addicted online gaming reported significantly higher social anxiety levels than non-problematic or engaged gamers [43, 77, 80, 83,84,85, 94, 97, 100, 101, 111]. Furthermore, in a possible bidirectional relationship [136], problematic online gaming and levels of social anxiety might mutually affect and reinforce each other. Indeed, as Lo et al. [22] found that the amount of social anxiety might increase when individuals spent more time playing online games, Wang et al. [80] and the longitudinal findings of Gentile et al. [106] showed the predictive role of the problematic (mobile) online gaming on social anxiety, especially among younger individuals. Nevertheless, overall, social anxious symptoms emerged as a pivotal risk and predictive factor of problematic online gaming [1, 10, 15, 72, 78, 88, 103]. In this regard, online gamers who suffer from social phobic symptoms appeared more likely to indulge in the virtual reality and more prone to develop a problematic online gaming, likely to avoid real life face-to-face social distress [73]. Therefore, the mutual predictive effect of social anxiety and problematic online gaming has been largely explored and frequently found in both young and adult individuals.

Several studies have defined social anxiety, depressive symptoms, self-esteem, and loneliness as strongly inter-related constructs [137] that have been extensively treated as risk factors for or of problematic Internet-related activities [7, 9, 22, 138,139,140,141]. More specifically, in addition to social anxiety, the problematic online gaming has been explored in association with depression, self-esteem, and loneliness [24,25,26,27,28, 131]. Similarly, the reviewed studies confirmed a strong association and a mutual relationship between these psychosocial and comorbid factors (especially depression and loneliness) and problematic online gaming [15, 43, 78,79,80, 94, 97, 98, 100, 106]. Furthermore, interestingly, Martončik & Lokša [71] reported a reduction of social anxiety and loneliness among the WoW gamers, suggesting that likely online players who do not feel accepted in offline world might turn to the video games’ worlds where they might perceive less threat to their social status. These controversial findings seem to reflect the complexity of the relationship between problematic online gaming and psychosocial/comorbidity issues [94]. Overall, the problematic online gaming might be defined as a complex psychological health condition which involves a feature of everyday life activities with potential negative outcomes. Indeed, although online gaming might offer an alternative context in which individuals can experiment personal social competences, reducing stress, problems, and isolation through online social interactions [16,17,18,19, 30], it might concurrently limit social experiences in face-to-face contexts when the online life starts to overshadow the offline one [23, 80, 94, 106]. Consequently, following the theoretical work of Caplan [7], some gamers might find refuge in online games with decreasing depressive symptoms, social anxiety, and loneliness, whereas, in other gamers’ experiences, these correlates might increase, ensuring online socialization but failing in providing the needed face-to-face interactions.

Finally, in a compensatory Internet use model [20••, 98] by which addictive Internet-related activities might represent coping mechanisms to alleviate psychopathological symptoms and/or negative emotional states, people might use online gaming to counterbalance distress or negative situations in everyday life, carrying out a maladaptive coping strategy [31,32,33]. In this regard, according to the Yee’s [129] construct of motivations to play, the escapism has been identified as motivation to play that strongly predicts problematic gaming [16, 31, 32, 142,143,144], especially in interaction with negative affects [111, 143, 145,146,147,148]. Overall, in line with previous studies [36••, 37, 74, 112], a new conceptualization of problematic online gaming and its related screening and assessment tools distinguishing between high engagement and pathological involvement in online videogames appear crucial.

Limitations and Conclusions

The results of the present review should be considered in view of the examined studies’ limitations. Firstly, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits the formal test of causality between social anxiety and problematic online gaming; thus, more longitudinal studies are needed to clarify the direction of their relationship. Secondly, studies largely used self-report methods which might be influenced by well-known bias, such as the lack of answer accuracy and social desirability. Furthermore, future studies should evaluate the relationship between social anxiety and problematic online gaming in interactions with other variables, contributing to the research field concerning the protective and predictive factors of problematic videogames use. Finally, the problematic online gaming among female users and gender-related differences in gaming habits are still understudied issues. However, the specific limitations of the present review should be considered. Firstly, the problematic online gaming research field is extremely prolific and largely explored and only studies published within the last ten years have been included in the present study. Consequently, this review might have excluded some relevant studies published more than ten years ago. Secondly, due to the electronic search of the studies, some not non-indexed papers into in the involved databases might have been missed. Finally, this review was based on English-language studies which excluded a significant proportion of the literature (especially East Asian).

Despite the limitations, the present review examined the literature of the last ten years concerning the association between problematic online gaming and social anxiety. According to King et al. [38••], studies on gaming behavior should include measures of comorbidity, thus addressing questions regarding the presence of other mental disorders. The current review of the literature confirmed a strong relationship among online gaming disorder and other psychosocial and comorbid factors, especially social anxiety, depression, and loneliness, thus reinforcing that great attention should be paid to the problematic or excessive online gaming as a maladaptive coping strategy for the psychopathological symptoms and/or negative emotional states regulation.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Lee BW, Leeson PRC. Online gaming in the context of social anxiety. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;29(2):473–82. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000070.

Rapee RM, Heimberg RG. A cognitive-behavioral model of anxiety in social phobia. Behav Res Ther. 1997;35(8):741–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967[97]00022-3.

McKenna KY, Bargh JA. Causes and consequences of social interaction on the Internet: a conceptual framework. Media Psychol. 1999;1(3):249–69. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532785xmep0103_4.

Ng BD, Wiemer-Hastings P. Addiction to the internet and online gaming. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2005;8(2):110–3. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2005.8.110.

Peters CS, Malesky LA Jr. Problematic usage among highly-engaged players of massively multiplayer online role playing games. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11(4):481–4. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.0140.

Caplan SE. Preference for online social interaction: a theory of problematic Internet use and psychosocial well-being. Commun Res. 2003;30(6):625–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650203257842.

Caplan SE. Relations among loneliness, social anxiety, and problematic Internet use. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2007;10(2):234–42. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9963.

Caplan SE. Theory and measurement of generalized problematic Internet use: a two-step approach. Comput Hum Behav. 2010;26(5):1089–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.012.

Lee BW, Stapinski LA. Seeking safety on the internet: relationship between social anxiety and problematic internet use. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26(1):197–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.11.001.

Cole SH, Hooley JM. Clinical and personality correlates of MMO gaming: anxiety and absorption in problematic internet use. Soc Sci Comput Rev. 2013;31(4):424–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439312475280.

Dalbudak E, Evren C, Aldemir S, Evren B. The severity of Internet addiction risk and its relationship with the severity of borderline personality features, childhood traumas, dissociative experiences, depression and anxiety symptoms among Turkish university students. Psychiatry Res. 2014;219(3):577–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.02.032.

Fayazi M, Hasani J. Structural relations between brain-behavioral systems, social anxiety, depression and internet addiction: with regard to revised Reinforcement Sensitivity Theory (r-RST). Comput Hum Behav. 2017;72:441–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.068.

Harman JP, Hansen CE, Cochran ME, Lindsey CR. Liar, liar: Internet faking but not frequency of use affects social skills, self-esteem, social anxiety, and aggression. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2005;8(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2005.8.1.

Pilling S, Mayo-Wilson E, Mavranezouli I, Kew K, Taylor C, Clark DM. Recognition, assessment and treatment of social anxiety disorder: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ. 2013;346: f2541. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f2541.

Wei HT, Chen MH, Huang PC, Bai YM. The association between online gaming, social phobia, and depression: an internet survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):92. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-12-92.

Billieux J, Van der Linden M, Achab S, Khazaal Y, Paraskevopoulos L, Zullino D, Thorens G. Why do you play World of Warcraft? An in-depth exploration of self-reported motivations to play online and in-game behaviours in the virtual world of Azeroth. Comput Hum Behav. 2013;29(1):103–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.021.

Demetrovics Z, Urbán R, Nagygyörgy K, Farkas J, Zilahy D, Mervó B, Harmath E. Why do you play? The development of the motives for online gaming questionnaire (MOGQ). Behav Res Methods. 2011;43(3):814–25. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-011-0091-y.

Mills, D. J., Li, W., & Marchica, L. (2019). Original paper negative affect, life satisfaction, and internet gaming disorder: exploring the mediating effect of coping and the moderating effect of passion. World, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.22158/wjssr.v6n1p45

Schneider LA, King DL, Delfabbro PH. Maladaptive coping styles in adolescents with Internet gaming disorder symptoms. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2018;16(4):905–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9756-9.

•• Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014a). A conceptual and methodological critique of internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31 (1), 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059 [Not done in the last 3 years—but the article is important since it proposed a new conceptualization of Internet and its applications use, by suggesting that people might use Internet to counterbalance distress or negative situations in real-life experiences].

Giardina, A., Di Blasi, M., Schimmenti, A., King, D. L., Starcevic, V., & Billieux, J. (2021). Online gaming and prolonged self-isolation: evidence from Italian gamers during the COVID-19 outbreak. https://doi.org/10.36131/cnfioritieditore20210106

Lo VH, Wei R. Exposure to Internet pornography and Taiwanese adolescents’ sexual attitudes and behavior. J Broadcast Electron Media. 2005;49(2):221–37. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15506878jobem4902_5.

Hussain Z, Griffiths MD. Excessive use of massively multi-player online role-playing games: a pilot study. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2009;7(4):563. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-009-9202-8.

Andreassen CS, Billieux J, Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Demetrovics Z, Mazzoni E, Pallesen S. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: a large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(2):252. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000160.

Bargeron AH, Hormes JM. Psychosocial correlates of internet gaming disorder: psychopathology, life satisfaction, and impulsivity. Comput Hum Behav. 2017;68:388–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.029.

Beard CL, Wickham RE. Gaming-contingent self-worth, gaming motivation, and internet gaming disorder. Comput Hum Behav. 2016;61:507–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.046.

Laconi S, Pirès S, Chabrol H. Internet gaming disorder, motives, game genres and psychopathology. Comput Hum Behav. 2017;75:652–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.012.

Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM, Gentile DA. The Internet gaming disorder scale. Psychological Assessment. 2015;27(2):567. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000062.

Pontes HM, Griffiths MD. Measuring DSM-5 Internet gaming disorder: development and validation of a short psychometric scale. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;45:137–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.12.006.

Jansz J, Martens L. Gaming at a LAN event: the social context of playing video games. New media & Society. 2005;7(3):333–55. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1461444805052280.

Di Blasi M, Giardina A, Giordano C, Lo Coco G, Tosto C, Billieux J, Schimmenti A. Problematic video game use as an emotional coping strategy: evidence from a sample of MMORPG gamers. Journal of Behavioural Addictions. 2019;8(1):25–34. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.02.

Di Blasi M, Giardina A, Coco GL, Giordano C, Billieux J, Schimmenti A. A compensatory model to understand dysfunctional personality traits in problematic gaming: the role of vulnerable narcissism. Personality Individ Differ. 2020;160: 109921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.109921.

Schimmenti A, Guglielmucci F, Barbasio CP, Granieri A. Attachment disorganization and dissociation in virtual worlds: a study on problematic Internet use among players of online role playing games. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2012;9(5):195–202.

Bean AM, Nielsen RK, Van Rooij AJ, Ferguson CJ. Video game addiction: the push to pathologize video games. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2017;48(5):378. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000150.

Aarseth, E., Bean, A. M., Boonen, H., Colder Carras, M., Coulson, M., Das, D., … & Van Rooij, A. (2017). Scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 Gaming Disorder proposal. Journal of Behavioral Addictions. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.088.

•• Billieux, J., Flayelle, M., Rumpf, H. J., & Stein, D. J. (2019). High involvement versus pathological involvement in video games: a crucial distinction for ensuring the validity and utility of gaming disorder. Current Addiction Reports, 6(3), 323–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-019-00259-x [The paper highlighted the crucial distinction between high engagement and pathological involvement in online videogames].

Billieux J, King DL, Achab S, Bowden-Jones H. Functional impairment matters in the screening and diagnosis of gaming disorder. Journal of Behavioural Addictions. 2017;6(3):285–9. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.036.

King, D. L., Chamberlain, S. R., Carragher, N., Billieux, J., Stein, D., Mueller, K., ... & Delfabbro, P. H. (2020b). Screening and assessment tools for gaming disorder: a comprehensive systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 77, 101831. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101831 [The review of the several measures used to assess the problematic gaming suggested that the gaming disorder research field would benefit from a standard international tool].

Van Rooij AJ, Van Looy J, Billieux J. Internet Gaming Disorder as a formative construct: Implications for conceptualization and measurement. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2017;71(7):445–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12404.

Van Rooij, A.J., Ferguson, C.J., Colder Carras, M., Bean, A. M., Helmersson, B., Etchells, P. J., ... & Przybylski, A. K. et al. (2018) A weak scientific basis for gaming disorder: let us err on the side of caution. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 7, 1–9. https://akjournals.com/view/journals/2006/7/1/article-p1.xml. Accessed March 2021.

Hoff RA, Howell JC, Wampler J, Krishnan-Sarin S, Potenza MN. Differences in associations between problematic video-gaming, video-gaming duration, and weapon-related and physically violent behaviors in adolescents. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;121:47–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.11.005.

Holtz P, Appel M. Internet use and video gaming predict problem behavior in early adolescence. J Adolesc. 2011;34(1):49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.02.004.

Van Rooij AJ, Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD, Shorter GW, Schoenmakers TM, Van De Mheen D. The (co-) occurrence of problematic video gaming, substance use, and psychosocial problems in adolescents. J Behav Addict. 2014;3(3):157–65. https://doi.org/10.1556/jba.3.2014.013.

American Psychiatric Association (APA). Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed) (DSM). Washington, DC: Author; 2013.

King DL, Delfabbro PH. Internet gaming disorder treatment: a review of definitions of diagnosis and treatment outcome. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2014;70(10):942–55. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22097.

Zajac K, Ginley MK, Chang R, Petry NM. Treatments for Internet gaming disorder and Internet addiction: a systematic review. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2017;31(8):979. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000315.

World Health Organization (2019) Addictive behaviours: Gaming disorder. Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/q-a-detail/addictive-behaviours-gaming-disorder. Accessed March 2021.

Billieux J, Schimmenti A, Khazaal Y, Maurage P, Heeren A. Are we overpathologizing everyday life? A tenable blueprint for behavioral addiction research. J Behav Addict. 2015;4(3):119–23. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.009.

Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Billieux J, Pontes HM. The evolution of Internet addiction: a global perspective. Addict Behav. 2016;53:193–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.11.001.

Kardefelt‐Winther, D., Heeren, A., Schimmenti, A., van Rooij, A., Maurage, P., Carras, M., ... & Billieux, J. (2017). How can we conceptualize behavioural addiction without pathologizing common behaviours?. Addiction, 112(10), 1709-1715. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13763

King DL, Delfabbro PH. Issues for DSM-V: Video-gaming disorder? Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;47:20–2. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0004867412464065.

King DL, Billieux J, Carragher N, Delfabbro PH. Face validity evaluation of screening tools for gaming disorder: scope, language, and overpathologizing issues. J Behav Addict. 2020;9(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00001.

Ko CH, Lin HC, Lin PC, Yen JY. Validity, functional impairment and complications related to Internet gaming disorder in the DSM-5 and gaming disorder in the ICD-11. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;54(7):707–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0004867419881499.

Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD, Pontes HM. Chaos and confusion in DSM-5 diagnosis of Internet Gaming Disorder: issues, concerns, and recommendations for clarity in the field. J Behav Addict. 2017;6(2):103–9. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.062.

Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD, Pontes HM. DSM-5 Diagnosis of Internet Gaming Disorder: some ways forward in overcoming issues and concerns in the gaming studies field. Response to the commentaries. Journal of Behavioural Addictions. 2017;6(2):133–41. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.032.

Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Lopez-Fernandez O, Pontes HM. Problematic gaming exists and is an example of disordered gaming: commentary on: Scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 Gaming Disorder proposal (Aarseth et al.). Journal of Behavioral Addictions. 2017;6(3):296–301. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.037.

Pontes HM. Investigating the differential effects of social networking site addiction and Internet gaming disorder on psychological health. J Behav Addict. 2017;6(4):601–10. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.075.

Starcevic V, Billieux J. Does the construct of Internet addiction reflect a single entity or a spectrum of disorders? Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2017;14(1):5–10.

Haagsma MC, Caplan SE, Peters O, Pieterse ME. A cognitive-behavioral model of problematic online gaming in adolescents aged 12–22 years. Comput Hum Behav. 2013;29(1):202–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.08.006.

Lemos IL, Cardoso A, Sougey EB. Cross-cultural adaptation and evaluation of the psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the Video Game Addiction Test. Computers in Human Behaviour. 2016;55:207–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.019.

Männikkö N, Billieux J, Kääriäinen M. Problematic digital gaming behavior and its relation to the psychological, social and physical health of Finnish adolescents and young adults. J Behav Addict. 2015;4(4):281–8. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.4.2015.040.

Milani, L., Camisasca, E., Ionio, C., Miragoli, S., & Di Blasio, P. (2019). Video games use in childhood and adolescence: social phobia and differential susceptibility to media effects. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 1359104519882754. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1359104519882754

Kashdan TB, Herbert JD. Social anxiety disorder in childhood and adolescence: current status and future directions. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2001;4(1):37–61. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009576610507.

King DL, Delfabbro PH, Griffiths MD, Gradisar M. Assessing clinical trials of Internet addiction treatment: a systematic review and CONSORT evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31:1110–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.06.009.

Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Internet gaming addiction: a systematic review of empirical research. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2012;10:278–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-011-9318-5.

Peng W, Liu M. Online gaming dependency: a preliminary study in China. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010;13(3):329–33. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0082.

Thomas NJ, Martin FH. Video-arcade game, computer game and Internet activities of Australian students: participation habits and prevalence of addiction. Aust J Psychol. 2010;62:59–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530902748283.

American Psychological Association. (2021). Developing adolescents: A reference for professionals. http://www.apa.org/topics/teens/developing-adolescents-professionals-reference.

Vannucci A, Simpson EG, Gagnon S, Ohannessian CM. Social media use and risky behaviors in adolescents: a meta-analysis. J Adolesc. 2020;79:258–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.01.014.

Fam JY. Prevalence of internet gaming disorder in adolescents: a meta-analysis across three decades. Scand J Psychol. 2018;59:524–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12459.

Martončik M, Lokša J. Do World of Warcraft (MMORPG) players experience less loneliness and social anxiety in online world (virtual environment) than in real world (offline)? Comput Hum Behav. 2016;56:127–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.035.

Sioni SR, Burleson MH, Bekerian DA. Internet gaming disorder: social phobia and identifying with your virtual self. Computers in Human Behaviour. 2017;71:11–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.044.

Rosliana, L., & Widiandari, A. (2020). Online Game and the Hikikomori Phenomenon in Japan. In E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 202, p. 07080). EDP Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1051/e3sconf/202020207080

Stavropoulos V, Anderson EE, Beard C, Latifi MQ, Kuss D, Griffiths M. A preliminary cross-cultural study of Hikikomori and Internet Gaming Disorder: the moderating effects of game-playing time and living with parents Addictive Behaviors Reports. 2019;9: 100137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abrep.2018.10.001.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7): e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

Lemmens JS, Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Development and validation of a game addiction scale for adolescents. Media Psychol. 2009;12(1):77–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213260802669458.

Phan O, Prieur C, Bonnaire C, Obradovic I. Internet gaming disorder: exploring its impact on satisfaction in life in PELLEAS adolescent sample. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17010003.

Vanzoelen D, Caltabiano ML. The role of social anxiety, the behavioural inhibition system and depression in online gaming addiction in adults. Journal of Gaming & Virtual Worlds. 2016;8(3):231–45. https://doi.org/10.1386/jgvw.8.3.231_1.

Sheng, J. R., & Wang, J. L. (2019). Development and psychometric properties of the problematic mobile video gaming scale. Current Psychology, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00415-6

Wang HZ, Sheng JR, Wang JL. The association between mobile game addiction and depression, social anxiety, and loneliness. Front Public Health. 2019;7:247. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00247.

Khalil, S. A., Kamal, H., & Elkouly, H. (2020). The prevalence of problematic internet use among a sample of Egyptian adolescents and its psychiatric comorbidities. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 0020764020983841. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020983841

Sigerson L, Li AYL, Cheung MWL, Luk JW, Cheng C. Psychometric properties of the Chinese internet gaming disorder scale. Addict Behav. 2017;74:20–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.05.031.

Subramaniam M, Chua BY, Abdin E, Pang S, Satghare P, Vaingankar JA, Chong SA. Prevalence and correlates of Internet gaming problem among Internet users: results from an Internet survey. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2016;45(5):174–83.

Starcevic V, Choi TY, Kim TH, Yoo SK, Bae S, Choi BS, Han DH. Internet gaming disorder and gaming disorder in the context of seeking and not seeking treatment for video-gaming. J Psychiatr Res. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2020.06.007.

Müller KW, Beutel ME, Dreier M, Wölfling K. A clinical evaluation of the DSM-5 criteria for Internet Gaming Disorder and a pilot study on their applicability to further Internet-related disorders. J Behav Addict. 2019;8(1):16–24. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.7.2018.140.

Wölfling, K., Beutel, M. E., & Müller, K. W. (2016). OSV-S–skala zum onlinesuchtverhalten [AICA-S–Scale for the assessment of internet and computer game addiction]. Diagnostische Verfahren in der Psychotherapie [Diagnostic Measures in Psychotherapy], 362–366.

Chen SH, Weng LJ, Su YJ, Wu HM, Yang PF. Development of a Chinese Internet addiction scale and its psychometric study. Chinese Journal of Psychology. 2003;45(3):279–94.

Lopez-Fernandez O, Williams AJ, Kuss DJ. Measuring female gaming: gamer profile, predictors, prevalence, and characteristics from psychological and gender perspectives. Front Psychol. 2019;10:898. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00898.

Marino C, Canale N, Vieno A, Caselli G, Scacchi L, Spada MM. Social anxiety and Internet gaming disorder: the role of motives and metacognitions. J Behav Addict. 2020;9(3):617–28. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00044.

Severo, R. B., Soares, J. M., Affonso, J. P., Giusti, D. A., de Souza Junior, A. A., de Figueiredo, V. L., ... & Pontes, H. M. (2020). Prevalence and risk factors for internet gaming disorder. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 42(5), 532-535. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2019-0760

Wang HY, Cheng C. Psychometric evaluation and comparison of two gaming disorder measures derived from the DSM-5 and ICD-11 frameworks. Front Psych. 2020;11:1490. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.577366.

Kircaburun K, Griffiths MD, Billieux J. Psychosocial factors mediating the relationship between childhood emotional trauma and internet gaming disorder: a pilot study. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2019;10(1):1565031. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1565031.

Bányai, F., Zsila, Á., Király, O., Maraz, A., Elekes, Z., Griffiths, M. D., ... & Demetrovics, Z. (2017). Problematic social media use: results from a large-scale nationally representative adolescent sample. PLoS One, 12(1), e0169839. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0169839

Van Rooij AJ, Schoenmakers TM, Van de Eijnden RJ, Van de Mheen D. Compulsive internet use: the role of online gaming and other internet applications. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(1):51–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.12.021.

Meerkerk GJ, Van Den Eijnden RJ, Vermulst AA, Garretsen HF. The compulsive internet use scale (CIUS): some psychometric properties. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2009;12(1):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0181.

Van Rooij AJ, Schoenmakers TM, Van den Eijnden RJ, Vermulst AA, van de Mheen D. Video game addiction test: validity and psychometric characteristics. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2012;15(9):507–11. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2012.0007.

Colder Carras M, Van Rooij AJ, Van de Mheen D, Musci R, Xue QL, Mendelson T. Video gaming in a hyperconnected world: a cross-sectional study of heavy gaming, problematic gaming symptoms, and online socializing in adolescents. Comput Hum Behav. 2017;68:472–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.060.

Van Rooij AJ, Ferguson CJ, Van de Mheen D, Schoenmakers TM. Time to abandon Internet Addiction? Predicting problematic Internet, game, and social media use from psychosocial well-being and application use. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2017;14(1):113–21.

Ko CH, Liu GC, Hsiao S, Yen JY, Yang MJ, Lin WC, et al. Brain activities associated with gaming urge of online gaming addiction. J Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:739–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.09.012.

Hyun GJ, Han DH, Lee YS, Kang KD, Yoo SK, Chung US, Renshaw PF. Risk factors associated with online game addiction: a hierarchical model. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;48:706–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.008.

Park JH, Han DH, Kim BN, Cheong JH, Lee YS. Correlations among social anxiety, self-esteem, impulsivity, and game genre in patients with problematic online game playing. Psychiatry Investig. 2016;13(3):297. https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2016.13.3.297.

Young KS. Psychology of computer use: XL. Addictive use of the Internet: a case that breaks the stereotype. Psychological Reports. 1996;79(3):899–902. https://doi.org/10.2466/2Fpr0.1996.79.3.899.

Karaca, S., Karakoc, A., Gurkan, O. C., Onan, N., & Barlas, G. U. (2020). Investigation of the online game addiction level, sociodemographic characteristics and social anxiety as risk factors for online game addiction in middle school students. Community Mental Health Journal, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00544-z

Horzum, M. B., Tuncay, A. R. A. S., & BALTA, Ö. Ç. (2008). Computer game addiction scale for children. Türk Psikolojik Danışma ve Rehberlik Dergisi, 3(30), 76–88. Retrieved from https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/tpdrd/issue/21450/229637. Accessed March 2021.

Gentile D. Pathological video-game use among youth ages 8 to 18: A national study. Psychological Science. 2009;20(5):594–602. https://doi.org/10.1111/2Fj.1467-9280.2009.02340.x.

Gentile DA, Choo H, Liau A, Sim T, Li D, Fung D, Khoo A. Pathological video game use among youths: a two-year longitudinal study. Pediatrics. 2011;127(2):e319–29. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-1353.

Caplan SE. Problematic Internet use and psychosocial well-being: development of a theory-based cognitive-behavioural measurement instrument. Computers in Human Behaviour. 2002;18:553–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(02)00004-3.

Davis RA. A cognitive-behavioural model of pathological Internet use. Computers in Human Behaviour. 2001;17:187–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(00)00041-8.

Kardefelt-Winther D. Problematizing excessive online gaming and its psychological predictors. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;31:118–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.017.

Sauter M, Braun T, Mack W. Social context and gaming motives predict mental health better than time played: an exploratory regression analysis with over 13,000 video game players. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2021;24(2):94–100. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2020.0234.

Lehenbauer-Baum M, Klaps A, Kovacovsky Z, Witzmann K, Zahlbruckner R, Stetina BU. Addiction and engagement: an explorative study toward classification criteria for internet gaming disorder. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2015;18(6):343–9. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0063.

Charlton, D. P., & Danforth, I. D. W. (2007). Distinguishing addiction and high engagement in the context of online game playing. Psychology: Journal Articles (Peer-Reviewed). Paper 3. http://digitalcommons.bolton.ac.uk/psych_journalspr/3. Accessed March 2021.

Connor KM, Davidson JR, Churchill LE, Sherwood A, Weisler RH, Foa E. Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN): new self-rating scale. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176(4):379–86. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.176.4.379.

D’El Rey GJF, Lacava JPL, Cardoso R. Internal consistency of the Portuguese version of the Mini-Social Phobia Inventory (Mini-SPIN). Archives of Clinical Psychiatry (São Paulo). 2007;34(6):266–9. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0101-60832007000600002.

Weeks JW, Spokas ME, Heimberg RG. Psychometric evaluation of the mini-social phobia inventory (Mini-SPIN) in a treatment-seeking sample. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24(6):382–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20250.

Gori, A., Giannini, M., Socci, S., Luca, M., Dewey, D. E., Schuldberg, D., et al. (2013). Assessing social anxiety disorder: psychometric properties of the Italian social phobia inventory (ISPIN). Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 10(1), 37. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/psych_pubs/11

La Greca AM, Lopez N. Social anxiety among adolescents: linkages with peer relations and friendships. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1998;26(2):83–94. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022684520514.

La Greca AM, Stone WL. Social anxiety scale for children-revised: factor structure and concurrent validity. J Clin Child Psychol. 1993;22(1):17–27. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp2201_2.

La Greca AM, Dandes SK, Wick P, Shaw K, Stone WL. Development of the Social Anxiety Scale for Children: reliability and concurrent validity. J Clin Child Psychol. 1988;17(1):84–91. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp1701_11.

Mattick RP, Clarke JC. Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36(4):455–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967[97]10031-6.

Peters L, Sunderland M, Andrews G, Rapee RM, Mattick RP. Development of a short form Social Interaction Anxiety (SIAS) and Social Phobia Scale (SPS) using nonparametric item response theory: the SIAS-6 and the SPS-6. Psychol Assess. 2012;24(1):66. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024544.

Heimberg RG, Horner KJ, Juster HR, Safren SA, Brown EJ, Schneier FR, Liebowitz MR. Psychometric properties of the Liebowitz social anxiety scale. Psychol Med. 1999;29(1):199–212.

Watson D, Friend R. Measurement of social-evaluative anxiety. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1969;33(4):448. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0027806.

Demir T, Eralp-Demir D, Türksoy N, Özmen E, Uysal Ö. Çocuklar için sosyal anksiyete ölçeğinin geçerlilik ve güvenilirliği. Düşünen Adam. 2000;13(1):42–8.

Wang, X. D.,Wang, X. L., & Ma, H. (1999). Handbook of mental health assessment scales (updated version). Chinese Journal of Mental Health, 244–246.

Nelemans SA, Meeus WH, Branje SJ, Van Leeuwen K, Colpin H, Verschueren K, Goossens L. Social Anxiety Scale for Adolescents (SAS-A) Short Form: longitudinal measurement invariance in two community samples of youth. Assessment. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116685808.

Hardt, J. (2008). The symptom checklist-27-plus (SCL-27-plus): a modern conceptualization of a traditional screening instrument. GMS Psycho-Social Medicine, 5.

Sheehan DV, Sheehan KH, Shytle RD, Janavs J, Bannon Y, Rogers JE, Wilkinson B. Reliability and validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for Children and Adolescents (MINI-KID). J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(3):313–26. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.09m05305whi.

Yee N. Motivations for play in online games. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2006;9:772–5. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9.772.

Gentile, D. A., Bailey, K., Bavelier, D., Brockmyer, J. F., Cash, H., Coyne, S. M., ... & Young, K. (2017). Internet gaming disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics, 140(Supplement 2), S81-S85. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-1758H

Griffiths, M. D., Király, O., Pontes, H. M., & Demetrovics, Z. (2015). An overview of problematic gaming. In E. Aboujaoude & V. Starcevic (Eds.), Mental health in the digital age: Grave dangers, great promise (pp. 27–45). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med/9780199380183.003.0002.

Bonetti L, Campbell MA, Gilmore L. The relationship of loneliness and social anxiety with children’s and adolescents’ online communication. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010;13(3):279–85. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0215.

Casale S, Tella L, Fioravanti G. Preference for online social interactions among young people: direct and indirect effects of emotional intelligence. Personality Individ Differ. 2013;54(4):524–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.10.023.

Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Social consequences of the Internet for adolescents: a decade of research. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2009;18(1):1–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01595.x.

Valkenburg PM, Peter J. Online communication among adolescents: an integrated model of its attraction, opportunities, and risks. J Adolesc Health. 2011;48(2):121–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.08.020.

Slater MD. Reinforcing spirals: the mutual influence of media selectivity and media effects and their impact on individual behavior and social identity. Commun Theory. 2007;17(3):281–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00296.x.

Leary MR. Responses to social exclusion: social anxiety, jealousy, loneliness, depression, and low self-esteem. J Soc Clin Psychol. 1990;9(2):221–9. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1990.9.2.221.

Boursier, V., Gioia, F., Musetti, A., & Schimmenti, A. (2020). Facing loneliness and anxiety during the COVID-19 isolation: the role of excessive social media use in a sample of Italian adults. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11. doi: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.586222

Boursier V, Musetti A, Gioia F, Flayelle M, Billieux J, Schimmenti A. Is watching TV series an adaptive coping strategy during the COVID-19 pandemic? Insights from an Italian community sample. Front Psych. 2021;12:554. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.599859.

Gioia F, Fioravanti G, Casale S, Boursier V. The effects of the fear of missing out on people’s social networking sites use during the COVID-19 pandemic: the mediating role of online relational closeness and individuals’ online communication attitude. Front Psych. 2021;12:146. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.620442.

Bozoglan B, Demirer V, Sahin I. Loneliness, self-esteem, and life satisfaction as predictors of Internet addiction: a cross-sectional study among Turkish university students. Scand J Psychol. 2013;54(4):313–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12049.

Ballabio M, Griffiths MD, Urbán R, Quartiroli A, Demetrovics Z, Király O. Do gaming motives mediate between psychiatric symptoms and problematic gaming? An empirical survey study. Addiction Research & Theory. 2017;25(5):397–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2017.1305360.

Bowditch L, Chapman J, Naweed A. Do coping strategies moderate the relationship between escapism and negative gaming outcomes in World of Warcraft (MMORPG) players? Comput Hum Behav. 2018;86:69–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.030.

Schimmenti A, Infanti A, Badoud D, Laloyaux J, Billieux J. Schizotypal personality traits and problematic use of massively-multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs). Comput Hum Behav. 2017;74:286–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.048.

Billieux, J., Deleuze, J., Griffiths, M. D., & Kuss, D. J. (2015a). Internet gaming addiction: the case of massively multiplayer online role-playing games. Textbook of Addiction Treatment: International perspectives, 1515-1525. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-88-470-5322-9_105

Chang SM, Hsieh GM, Lin SS. The mediation effects of gaming motives between game involvement and problematic Internet use: escapism, advancement and socializing. Comput Educ. 2018;122:43–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.03.007.

Király O, Griffiths MD, Demetrovics Z. Internet gaming disorder and the DSM-5: conceptualization, debates, and controversies. Curr Addict Rep. 2015;2(3):254–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0066-7.

Maroney N, Williams BJ, Thomas A, Skues J, Moulding R. A stress-coping model of problem online video game use. Int J Ment Heal Addict. 2019;17(4):845–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9887-7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gioia, F., Colella, G.M. & Boursier, V. Evidence on Problematic Online Gaming and Social Anxiety over the Past Ten Years: a Systematic Literature Review. Curr Addict Rep 9, 32–47 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-021-00406-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-021-00406-3