Abstract

Introduction

Existing research tackling the influence of pharmaceutical trade-name types upon physician prescription behavior is rather minimal.

Objective

The aim of this study was to investigate physicians’ perception of pharmaceutical trade (brand) names in Jordan’s private sector using two approaches—a real-world setting approach, and another simulated approach.

Methods

For the real-world setting approach, 13 trade-name types were used to test physician perception versus their prescription predictors (clarified benefits, conveyed efficacy, enhanced memorability, and reduced confusion), then linked to physician perception in terms of prescription behavior, as measured by increased prescription preference for each of the trade-name types. Regarding the simulated approach, a sample of 100 pharmaceutical product trade names was utilized to demonstrate the relationship between their unit-wise sales and the type of trade name to which they belong.

Results

Results for the real-world setting approach revealed that physicians had a favorable perception of names that are derived from the site of action, those that are experiential, and functional names. A neutral perception was demonstrated for name types with a hint of competitive advantage, as well as short names. An unfavorable perception was observed for evocative names, geographical location-derived names, fricative names, manufacturer-derived names, and poetic and plosive names. As for the simulated approach, unit-wise sales were highest for functional as well as evocative trade-name types.

Conclusions

The pharmaceutical trade-name types that are most favorable are those that reflect the drug’s site of action, experiences delivered, and function. It was recommended that pharmaceutical companies choose more appropriate trade names for their products based on physicians’ preference.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kotler P, Armstrong G. Principles of marketing. Upper Saddle, NJ: Pearson in; 2011.

Keller KL. Strategic brand management: building, measuring, and managing brand equity. Upper Saddle, NJ: Pearson Education; 1998.

Lane SD. Interpersonal communication: competence and contexts. Upper Saddle, NJ: Pearson; 2010.

Robin R. Brand matters: the lingua franca of pharmaceutical brand names. First published in Pharmaceutical Branding Strategies: Thoughtleader perspectives on Brand Building, Global Business Insights; 2006.

Robertson K. Strategically desirable brand name characteristics. J Consum Mark. 1989;6:61–71.

Bloomfield L. Language. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1984.

Merriam L. Styles and types of company and product names. Merriam Associates, Inc. Brand Strategies; 2009.

Building the perfect beast. The Igor naming guide. San Francisco: Igor; 2010.

Krechevsky C, Ciotola MP. Selecting a brand name that shines: avoiding the perils and pitfalls. Corp Couns. 2012;4:1–2.

Kenagy JW, Stein GC. Naming, labeling, and packaging of pharmaceuticals. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2001;58(21):2033–41.

Team HHCT. Jordan national health accounts 2010–2011: technical report no. 4. High Health Council; 2013.

Jordan pharmaceutical index. Intercontinental marketing services (IMS) Health; 2013.

Moss G, Schuiling I. A brand logic for pharma? A possible strategy based on FMCG experience. Int J Med Mark. 2004;4:55–62.

Building the perfect beast: the Igor naming guide. San Francisco: Igor; 2010.

Gangwal A, Gangwal A. Naming of drug molecules and pharmaceutical brands. J Curr Pharm Res. 2011;7:1–5.

Tavakol M, Dennick R. Making sense of Cronbach’s alpha. Int J Med Educ. 2011;2:53–5.

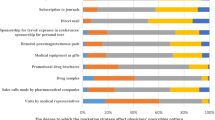

Ghaith A, Ibrahim ALA, Hani ALD. Investigating the effect of pharmaceutical companies’ gifts on doctors’ prescribing behavior in Jordan. Eur J Soc Sci. 2013;36:528–36.

Krejcie RV, Morgan DW. Determining sample size for research activities. Educ Psychol Meas. 1970;30:607–10.

Peterson RA, Ross I. How to name new brands. J Advert Res. 1972;12:29–34.

Klink RR. Creating brand names with meaning: the use of sound symbolism. Market Lett. 2000;11:5–20.

Shimp TA. Promotion management and marketing communications. Fort Worth (TX): The Dryden Press; 1993.

Pavia TM, Costa JA. The winning number: consumer perceptions of alpha-numeric brand names. J Mark. 1993;57:85–98.

Kohli C, Suri R. Brand names that work: a study of the effectiveness of different types of brand names. Mark Manag J. 2000;10:112–20.

Hillenbrand P, Alcauter S, Cervantes J, Barrios F. Better branding: brand names can influence consumer choice. J Prod Brand Manag. 2013;22:300–8.

Paivio A. Imagery and verbal processes. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York; 1971.

Lutz KA, Lutz RJ. Effects of interactive imagery on learning: application to advertising. J Appl Psychol. 1977;62:493–8.

Lowrey TM, Shrum LJ, Dubitsky TM. J Advert. 2003;32:7–17.

Heath TB, Chatterjee S, France KR. Using the phonemes of brand names to symbolize brand attributes. In: Bearden W, Parasuraman A, editors. The AMA EDUCATOR’S proceedings: enhancing knowledge development in marketing. Chicago: American Marketing Association; 1990;38–42.

Vandenbergh B, Adler K, Oliver L. Linguistic distinction among top brand names. J Advert Res. 1987;27:39–44.

Acknowledgments

This research received no grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. Hamsa Al-Aqqad, Muhammed Al-Zweiri, and Ibrahim Alabbadi declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Aqqad, H., Al-Zweiri, M. & Alabbadi, I. An Investigation of Physicians’ Perception of Pharmaceutical Trade Names in Jordan’s Private Sector Using Real-World and Simulated Approaches. Pharm Med 29, 169–178 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40290-015-0098-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40290-015-0098-2