Abstract

Introduction

Several different types of drugs acting on the central nervous system (CNS) have previously been associated with an increased risk of suicide and suicidal ideation (broadly referred to as suicide). However, a differential association between brand and generic CNS drugs and suicide has not been reported.

Objectives

This study compares suicide adverse event rates for brand versus generic CNS drugs using multiple sources of data.

Methods

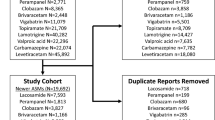

Selected examples of CNS drugs (sertraline, gabapentin, zolpidem, and methylphenidate) were evaluated via the US FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) for a hypothesis-generating study, and then via administrative claims and electronic health record (EHR) data for a more rigorous retrospective cohort study. Disproportionality analyses with reporting odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were used in the FAERS analyses to quantify the association between each drug and reported suicide. For the cohort studies, Cox proportional hazards models were used, controlling for demographic and clinical characteristics as well as the background risk of suicide in the insured population.

Results

The FAERS analyses found significantly lower suicide reporting rates for brands compared with generics for all four studied products (Breslow–Day P < 0.05). In the claims- and EHR-based cohort study, the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) was statistically significant only for sertraline (HR 0.58; 95% CI 0.38–0.88).

Conclusion

Suicide reporting rates were disproportionately larger for generic than for brand CNS drugs in FAERS and adjusted retrospective cohort analyses remained significant only for sertraline. However, even for sertraline, temporal confounding related to the close proximity of black box warnings and generic availability is possible. Additional analyses in larger data sources with additional drugs are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

World Health Organization. America’s State of Mind Report 2011 [cited 2017 Feb 09]. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js19032en/.

BBC. Research. Therapeutic Drugs for Central Nervous System (CNS) Disorders: Technologies and Global Markets 2010 [cited 2017 Feb 09]. http://www.bccresearch.com/market-research/pharmaceuticals/drugs-central-nervous-system-disorders-phm068a.html.

Fischer MA, Avorn J. Potential savings from increased use of generic drugs in the elderly: what the experience of Medicaid and other insurance programs means for a Medicare drug benefit. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2004;13(4):207–14.

Haas JS, Phillips KA, Gerstenberger EP, Seger AC. Potential savings from substituting generic drugs for brand-name drugs: medical expenditure panel survey, 1997–2000. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(11):891–7.

Express Scripts. Drug Trend Report 2016 [cited 2017 Feb 09]. https://lab.express-scripts.com/lab/drug-trend-report.

Gagne JJ, Choudhry NK, Kesselheim AS, Polinski JM, Hutchins D, Matlin OS, et al. Comparative effectiveness of generic and brand-name statins on patient outcomes: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(6):400–7.

Shrank WH, Hoang T, Ettner SL, Glassman PA, Nair K, DeLapp D, et al. The implications of choice: prescribing generic or preferred pharmaceuticals improves medication adherence for chronic conditions. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(3):332–7.

Shrank WH, Cox ER, Fischer MA, Mehta J, Choudhry NK. Patients’ perceptions of generic medications. Health Aff. 2009;28(2):546–56.

Brennan TA, Lee TH. Allergic to generics. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(2):126–30.

Crawford P, Feely M, Guberman A, Kramer G. Are there potential problems with generic substitution of antiepileptic drugs?: a review of issues. Seizure. 2006;15(3):165–76.

Desmarais JE, Beauclair L, Margolese HC. Switching from brand-name to generic psychotropic medications: a literature review. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2011;17(6):750–60.

Kesselheim AS, Darrow JJ. Hatch–Waxman turns 30: do we need a re-designed approach for the modern era. Yale J Health Pol’y L Ethics. 2015;15:293.

Danzis SD. The Hatch–Waxman act: history, structure, and legacy. Antitrust Law J. 2003;71(2):585–608.

Del Tacca M, Pasqualetti G, Di Paolo A, Virdis A, Massimetti G, Gori G, et al. Lack of pharmacokinetic bioequivalence between generic and branded amoxicillin formulations. A post-marketing clinical study on healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;68(1):34–42.

Seoane-Vazquez E, Rodriguez-Monguio R, Hansen R. Interchangeability, safety and efficacy of modified-release drug formulations in the USA: the case of opioid and other nervous system drugs. Clin Drug Investig. 2016;36(4):281–92.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Bupropion Hydrochloride Extended-Release 300 mg Bioequivalence Studies 2014 [cited 2017 Feb 09]. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/postmarketdrugsafetyinformationforpatientsandproviders/ucm322161.htm.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Methylphenidate Hydrochloride Extended Release Tablets (generic Concerta) made by Mallinckrodt and Kudco 2014 [cited 2017 Feb 09]. http://www.fda.gov/drugs/drugsafety/ucm422568.htm.

Borgheini G. The bioequivalence and therapeutic efficacy of generic versus brand-name psychoactive drugs. Clin Ther. 2003;25(6):1578–92.

Collett GA, Song K, Jaramillo CA, Potter JS, Finley EP, Pugh MJ. Prevalence of central nervous system polypharmacy and associations with overdose and suicide-related behaviors in Iraq and Afghanistan War veterans in VA care 2010–2011. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2016;3:45–52.

Valuck RJ, Libby AM, Sills MR, Giese AA, Allen RR. Antidepressant treatment and risk of suicide attempt by adolescents with major depressive disorder. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(15):1119–32.

Mosholder AD, Willy M. Suicidal adverse events in pediatric randomized, controlled clinical trials of antidepressant drugs are associated with active drug treatment: a meta-analysis. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(1–2):25–32.

Mihanovic M, Restek-Petrovic B, Bodor D, Molnar S, Oreskovic A, Presecki P. Suicidality and side effects of antidepressants and antipsychotics. Psychiatr Danub. 2010;22(1):79–84.

Rihmer Z, Gonda X. Suicide behaviour of patients treated with antidepressants. Neuropsychopharmacol Hung. 2006;8(1):13–6.

Fergusson D, Doucette S, Glass KC, Shapiro S, Healy D, Hebert P, et al. Association between suicide attempts and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: systematic review of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2005;330(7488):396.

Lavigne JE, Au A, Jiang R, Wang Y, Good CP, Glassman P, et al. Utilization of prescription drugs with warnings of suicidal thoughts and behaviours in the USA and the US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2009. J Pharm Health Serv Res. 2012;3(3):157–63.

Los Angeles Times. Generic drugs' hidden downside [cited 16 March 2017]. Available from: http://articles.latimes.com/2007/dec/17/news/OE-WAX17.

Vergouwen A, Bakker A. Adverse effects after switching to a different generic form of paroxetine: paroxetine mesylate instead of paroxetine HCl hemihydrate. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2002;146(17):811–2.

Margolese HC, Wolf Y, Desmarais JE, Beauclair L. Loss of response after switching from brand name to generic formulations: three cases and a discussion of key clinical considerations when switching. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(3):180–2.

Mofsen R, Balter J. Case reports of the reemergence of psychotic symptoms after conversion from brand-name clozapine to a generic formulation. Clin Ther. 2001;23(10):1720–31.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration. What is FAERS 2016 [cited 2016 June 15]. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/default.htm.

Sakaeda T, Tamon A, Kadoyama K, Okuno Y. Data mining of the public version of the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10(7):796–803.

Hansen RA, Qian J, Berg RL, Linneman JG, Seoane-Vazquez E, Dutcher S, et al. Comparison of outcomes following a switch from a brand to an authorized vs. independent generic drug. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/cpt.591.

Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: new-user designs. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;158(9):915–20.

Activities MDfR. Standardised MedDRA Queries 2017 [cited 2017 June 25]. http://www.meddra.org/how-to-use/tools/smqs.

Finley EP, Bollinger M, Noël PH, Amuan ME, Copeland LA, Pugh JA, et al. A national cohort study of the association between the polytrauma clinical triad and suicide-related behavior among US Veterans who served in Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(2):380–7.

Walkup JT, Townsend L, Crystal S, Olfson M. A systematic review of validated methods for identifying suicide or suicidal ideation using administrative or claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(Suppl 1):174–82.

Simon GE, Rutter CM, Peterson D, Oliver M, Whiteside U, Operskalski B, et al. Does response on the PHQ-9 depression questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death? Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(12):1195–202.

Olfson M, Marcus SC, Tedeschi M, Wan GJ. Continuity of antidepressant treatment for adults with depression in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(1):101–8.

Faught E, Duh MS, Weiner JR, Guerin A, Cunnington MC. Nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs and increased mortality: findings from the RANSOM Study. Neurology. 2008;71(20):1572–8.

van de Vrie-Hoekstra NW, de Vries TW, van den Berg PB, Brouwer OF, de Jong-van den Berg LT. Antiepileptic drug utilization in children from 1997–2005—a study from the Netherlands. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;64(10):1013–20.

Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130–9.

Almenoff J, Tonning JM, Gould AL, Szarfman A, Hauben M, Ouellet-Hellstrom R, et al. Perspectives on the use of data mining in pharmacovigilance. Drug Saf. 2005;28(11):981–1007.

Spruance SL, Reid JE, Grace M, Samore M. Hazard ratio in clinical trials. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48(8):2787–92.

Bewick V, Cheek L, Ball J. Statistics review 12: survival analysis. Crit Care. 2004;8(5):389–94.

Andermann F, Duh MS, Gosselin A, Paradis PE. Compulsory generic switching of antiepileptic drugs: high switchback rates to branded compounds compared with other drug classes. Epilepsia. 2007;48(3):464–9.

Shrank WH, Liberman JN, Fischer MA, Girdish C, Brennan TA, Choudhry NK. Physician perceptions about generic drugs. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(1):31–8.

Miller M. Questions & answers. I’ve been taking Zoloft Recently, my pharmacist filled my prescription with a generic form of the drug. Does the brand name matter? Harv Ment Health Lett Harv Med Sch. 2007;23(8):8.

Lane RM. SSRI-induced extrapyramidal side-effects and akathisia: implications for treatment. J Psychopharmacol. 1998;12(2):192–214.

Bohn J, Kortepeter C, Muñoz M, Simms K, Montenegro S, Dal Pan G. Patterns in spontaneous adverse event reporting among branded and generic antiepileptic drugs. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2015;97(5):508–17.

Iyer G, Marimuthu SP, Segal JB, Singh S. An algorithm to identify generic drugs in the FDA adverse event reporting system. Drug Saf. 2017;40(9):799–808.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

In the past 3 years, Richard A. Hansen has provided expert testimony for Daiichi Sankyo. Richard Hansen and Jingjing Qian also have received grant funding from US FDA Grant U01FD005272 and contract HHSF2232015101102C, and these grants are directly related to the general topic of this manuscript. Dr. Hansen also received funding from National Institute of Health grant 2R01GM097618-04, which is related to but did not directly fund this work. Ning Cheng, Md. Motiur Rahman, Yasser Alatawi, Jingjing Qian, Peggy L. Peissig, Richard L. Berg, and David Page have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study. Views expressed in written materials or publications and by speakers do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the Department of Health and Human Services; nor does any mention of trade names, commercial practices, or organization imply endorsement by the United States Government.

Funding

This study was supported by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration through Grant U01FD005272 and contract HHSF2232015101102C. A National Institute of Health Grant 2R01GM097618-04 provided related support but did not directly fund this study.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Auburn University Institutional Review Board for research involving human subjects (protocol 14-465 EP1410).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cheng, N., Rahman, M.M., Alatawi, Y. et al. Mixed Approach Retrospective Analyses of Suicide and Suicidal Ideation for Brand Compared with Generic Central Nervous System Drugs. Drug Saf 41, 363–376 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-017-0624-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-017-0624-0