Abstract

Introduction

Clinical information is needed to assess the causal relationship between a drug and an adverse drug reaction (ADR) in a reliable way. Little is known about the level of relevant clinical information about the ADRs reported by patients.

Objective

The aim was to determine to what extent patients report relevant clinical information about an ADR compared with their healthcare professional.

Methods

A retrospective analysis of all ADR reports on the same case, i.e., cases with a report from both the patient and the patient’s healthcare professional, selected from the database of the Dutch Pharmacovigilance Center Lareb, was conducted. The extent to which relevant clinical information was reported was assessed by trained pharmacovigilance assessors, using a structured tool. The following four domains were assessed: ADR, chronology, suspected drug, and patient characteristics. For each domain, the proportion of reported information in relation to information deemed relevant was calculated. An average score of all relevant domains was determined and categorized as poorly (≤45%), moderately (from 46 to 74%) or well (≥75%) reported. Data were analyzed using a paired sample t test and Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Results

A total of 197 cases were included. In 107 cases (54.3%), patients and healthcare professionals reported a similar level of clinical information. Statistical analysis demonstrated no overall differences between the groups (p = 0.126).

Conclusions

In a unique study of cases of ADRs reported by patients and healthcare professionals, we found that patients report clinical information at a similar level as their healthcare professional. For an optimal pharmacovigilance, both healthcare professionals and patient should be encouraged to report.

Similar content being viewed by others

Studies have demonstrated that patients are well capable of reporting possible ADRs. Little is known to what extent patients report relevant clinical information compared to their healthcare professional when reporting ADRs to a pharmacovigilance center. |

Analyzing cases of ADRs, reported by patients and their healthcare professionals, we found that the level of reporting relevant clinical information was similar between both groups. |

1 Introduction

Pharmacovigilance is the science about ‘the detection, assessment, understanding and prevention of adverse effects or any other drug related problems’ [1]. Due to the design of pre-marketing clinical trials, i.e., small and homogeneous populations monitored for short periods of time, not all possible adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are detected. Additional ADRs, some of them serious, may be identified once a drug is used more widely and under more diverse conditions, e.g., concurrent use with other drugs or problems in using drugs by patients [2].

Pharmacovigilance centers maintain the national spontaneous reporting systems. Spontaneous reports of possible ADRs are a valuable source of information, e.g., in the USA, spontaneous reports were the primary evidence source of drug safety issues resulting in drug safety communication from 2007 to 2009 [3]. Traditionally, reporting of possible ADRs was reserved for healthcare professionals. Only a few countries allowed patients to report their ADRs directly, for example, Australia since 1964 and the USA since 1969 [4]. Over the years, patient participation has increasingly been recognized as an important addition to pharmacovigilance [5, 6]. Studies demonstrated that they contributed to identifying new ADRs as well as new information about known ADRs [7–9]. More and more countries have started to accept ADR reports directly from patients, for example, the Netherlands in 2003, the UK in 2005 and Sweden in 2008 [4]. Since 2012, changes in the European pharmacovigilance legislation made it possible for patients of all European member states to report drug concerns directly to the national pharmacovigilance centers [5].

A recent review showed that patient reporting adds new information and perspectives about ADRs in a way otherwise unavailable, for example, information about the impact of ADRs on the patient’s daily life. It also identified gaps in knowledge that should be addressed to improve our understanding of the full potential and drawbacks of patient reporting [10]. One of these aspects is the quality of clinical information. To assess the causal relationship between exposure to a drug and an ADR in a reliable way, clinical information is needed [11]. Studies that have compared information reported by patients and healthcare professionals have so far focused on the completeness of information [12–24]. When it comes to causality assessment, an additional often ignored point of attention is the relevance of the clinical information provided. When a report lacks essential clinical information, it is difficult to assess the reported data. In contrast, a brief report can still provide sufficient clinical information if all relevant information has been reported for that specific case.

As far as we are aware, it has not been studied to what extent patients report relevant clinical information compared with health professionals, in particular, clinically relevant information needed to make causal assessments. The study aims to determine to what extent patients report relevant clinical information about an ADR compared with their healthcare professional.

2 Method

2.1 Study Setting and Design

We used the database of the Dutch Pharmacovigilance Center Lareb. Both patients and healthcare professionals are able to report possible drug concerns directly to Lareb by means of an electronic or paper reporting form. These forms contain standardized questions, of which some are mandatory in the electronic form. Also, reporters can give additional information in a free-text field. Both reporting forms obtain the same information, with the exception of a question about medical history, which is only present on the healthcare professionals reporting form. Reports from patients and healthcare professionals are handled in the same way for the case-by-case analysis, follow-up actions and signal detection.

The number of reports to the Dutch pharmacovigilance center continues to grow. In 2015, Lareb received about 8000 reports directly from patients and 6600 from healthcare professionals [25]. In the majority of cases, the ADR is either reported by the patient or the healthcare professional. Rarely, the patient and the patient’s healthcare professional send reports independently on the same case. For this study, we conducted a retrospective analysis of all reports on the same case, i.e., reported by the patient and the patient’s healthcare professional. This provided us the unique situation to directly compare the differences in clinical information reported by both groups.

Cases were identified as follows: all incoming reports were assessed case by case by a trained pharmacovigilance assessor. During this assessment, the reports were automatically screened for other reports on the same case by checking the reported ADR (based on the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities MedDRA ® Higher Level Term coding) [26], suspected drug, and patient’s date of birth and gender, using a time frame maximum of 1 year between both reporting dates. Using these data, the pharmacovigilance assessor determined if the reports were on the same case and labeled them accordingly in the database. This procedure is part of routine screening of all reports in the pharmacovigilance center Lareb.

2.2 Study Population

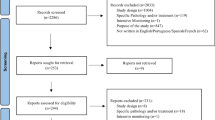

All cases of reports that were made on the same case in the period April 1, 2003 until October 1, 2015 were selected from the Lareb database. When a case had more than two reporters, e.g., one patient report and two healthcare professional reports, the case was included twice: patient versus healthcare professional 1 and patient versus healthcare professional 2. Exclusion criteria were as follows: all cases not including a patient report or a healthcare professional report; any cases received through pharmaceutical companies, since these were not directly sent to Lareb (e.g., other reporting forms may be used).

2.3 Outcomes

Our primary outcome was a comparison of the level of reporting of clinical information between patients and healthcare professionals. This was determined using a clinical documentation tool (ClinDoc) [27]. This tool was recently developed and tested by Lareb as part of the WEB-RADR project, work package 4 [28]. It provides a structured approach to assess the level at which relevant clinical data has been reported. Four domains were assessed: (1) description of the ADR, (2) chronology of the ADR, (3) suspected drug, and (4) patient characteristics. Each domain consisted of several subdomains (Table 1). To use this tool, first, the assessor indicated which subdomains were relevant in order to assess the report. Subsequently, the assessor indicated if this relevant information was present or absent. A score was calculated for each domain by dividing the number of subdomains with information present by the number of subdomains deemed relevant. The final score was the sum of the domain scores of all domains deemed relevant. The final score was categorized into one of three reporting level categories: well (≥75%), moderately (46–74%) or poorly (≤45%).

As a secondary outcome, we explored whether the proportions of information present in relation to the information deemed relevant was different for the individual (sub)domains. Because differences in the level of reporting for serious versus non-serious cases may be expected, we did a sub-analysis for (non)serious cases. Seriousness was assessed according to Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMs) criteria, which include ADRs leading to (prolongation of) hospitalization, life-threatening events, reactions leading to death, disabling events or congenital abnormalities or other events considered serious by medical judgment [29].

All included reports were scored by two pharmacovigilance assessors independently. All reports were reformatted so that the assessors were kept blind as to whether reports originated from a patient or a healthcare professional. In total, six experienced pharmacovigilance assessors were involved. Reports about the same case, i.e., the report of the patient and the one of the healthcare professional, were scored by the same assessors but were presented to them at random. Differences between scores for each domain were discussed until consensus was reached. Prior to scoring, all assessors were trained how to use the ClinDoc tool by means of scoring and discussing 15 reports.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

General characteristics of the included cases were explored using descriptive statistics. We used a paired sample t test for normally distributed data and a Wilcoxon signed rank test for non-parametric testing. Data normality was tested graphically using a histogram and numerically using Shapiro–Wilk test and a test for skewness. Statistical significance was based on p < 0.05. Data were analyzed using the statistical software program SPSS Statistics, version 22.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA).

3 Results

3.1 General Information Sample Characteristics

We included 197 cases with a report from the patient and their healthcare professional. There was one case reported by the patient and two healthcare professionals. All the other cases contained one patient and one healthcare professional report. A report may contain several ADRs. In total, 227 ADRs were reported by both reporters, with most ADRs belonging to the System Organ Classes ‘Nervous system disorders,’ ‘Psychiatric disorders,’ ‘Gastrointestinal disorders’ and ‘Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders.’ Of the reported cases, 66 (33.5%) were classified as serious, according to CIOMs criteria [29]. Two examples of the description of information given by patients and healthcare professionals are provided in Table 2.

For all reports, the two assessors agreed on the level of clinical information for a mean of eight reports (range 6–11). For cases that were scored differently, the level of clinical information mostly differed by one category. Only two assessors had one report for which the score differed by two categories. Differences between scores for each domain were discussed until consensus was reached.

3.2 Overall Reporting of Clinical Information

Of all cases, for 107 (54.3%), the patient and the healthcare professional reported the clinical information at the same level. If the level was different, in most cases (87.8%), reports differed by only one category (well vs. moderate or moderate vs. poor) and rarely (12.2%) by two categories (well vs. poor). For 34 cases (17.3%), the patient scored one category higher compared with their healthcare professional. For four cases (2.0%), the patient scored two categories higher. For 45 cases (22.8%), the healthcare professional scored one category higher compared with the patient, and for seven cases (3.6%), the healthcare professional scored two categories higher (Table 3a). Wilcoxon signed rank test demonstrated no statistically significant difference in category between groups (p = 0.126). Similar results were obtained when analyzing serious and non-serious cases separately (respectively, p = 0.196 and p = 0.356). For serious reports, 29 (43.9%) from patients and healthcare professionals on the same case were classified in the same category. For non-serious reports, this number was 78 (59.5%) (Table 3b, c).

3.3 Differences in Domains Scores

For the domains ‘ADR,’ ‘chronology’ and ‘suspected drug,’ patients and healthcare professionals scored in about 40% of cases similarly (i.e., scores differed less than 10%) (Fig. 1). Healthcare professionals had higher scores for the domain ‘patient characteristics’ and probably therefore also had more often higher final scores. It has to be noted that the domain ‘drug’ was found to be relevant in only 13 cases (6.6%).

Paired sample t test and Wilcoxon signed rank test showed that healthcare professionals had a statistically significantly higher score for the domains ‘patient characteristics’ and again probably therefore a higher final score. The mean difference of the percentage score for these domains was, however, found to be small, 65.7 versus 57.1% (p = 0.003) for ‘patient characteristics’ and 77.9 versus 74.7% (p = 0.04) for final score.

When the same analysis was performed using only the serious cases, healthcare professionals had a statistically significant higher score for the domains ‘ADR’ and ‘patient characteristics.’ The mean difference for the domain ‘ADR’ was small, 84.2 versus 75.6% (p = 0.02). For the domain ‘patient characteristics,’ the mean difference was 66.1 versus 55.5% (p = 0.04). When the analysis was performed using only the non-serious cases, healthcare professionals had a statistically significant higher score for the domain ‘patient characteristics.’ The mean difference was, however, small, 58.1 versus 65.3% (p = 0.03).

3.4 Differences in Subdomain Scores

The subdomain ‘concomitant medication’ (a subdomain of the domain ‘suspected drug’) was statistically significantly more often reported by healthcare professionals than patients (75 vs. 63.5%, p = 0.017). For the other subdomains, no statistically significant differences were found.

Remarkable findings were that ‘visual material,’ ‘lab values, tests’ and ‘patient’s life style and other risk factors’ were infrequently documented by both groups. In cases where these subdomains were considered to be relevant, respectively, 19, 25 and 20% of the patient reports and 20, 39 and 25% of the healthcare professional reports contained this information.

4 Discussion

Healthcare professionals and patients reported clinical information about the ADR on a comparable level for over half of the cases. For only one third of all cases, the patient had a lower score compared to their healthcare professional. Vice versa, patients had higher scores for almost one fifth of the reports. Rarely, we found large differences in the level of reporting of relevant information. Items included in the clinical documentation tool reflect items that are important for causality assessment. The results found in this study indicate that reports from patients are comparable to those of healthcare professionals when it comes to making a proper causality analysis.

Healthcare professionals more often reported information concerning ‘patient characteristics,’ but given the mean difference of 8.6%, we considered this finding negligible for daily pharmacovigilance practice. We saw the same pattern when analyzing serious reports separately. However, for these cases, healthcare professionals scored the domain ‘patient characteristic’ significantly higher compared with patients, with a mean difference of 10.6%. Healthcare professionals might see more need to provide this type of information. Furthermore, in cases of hospitalization or death, healthcare professionals may include the hospital discharge letter with their report. This letter provides information about patient characteristics. For patients, this hospital discharge letter is mostly not available.

Previous research about patient versus healthcare professional reporting demonstrated that overall, healthcare professionals reported more information related to the suspected drug, e.g., drug dosage and route of administration [21]. In the present study, information concerning the suspected drug was only relevant in a limited number of cases, such as a ‘brand name in case of an ADR after drug substitution.’ For these cases, mostly one subdomain was relevant for assessment of the report. Therefore, when this subdomain was present in the healthcare professional report (score of 100%) but lacking in the patient report (score of 0%), this resulted in a difference of 100%. Consequently, the mean difference (30.8%) seems to be large but has no practical relevance.

As far as we are aware, this is the first study to use reports from the patient and the patient’s healthcare professional on the same case. Due to this unique approach, we were able to directly compare the differences in clinical information reported by both groups. There may have been some selection bias, as a report had to be ‘interesting’ enough for both patients and healthcare professionals to report it independently. The motivation or reason for reporting has to be considered when exploring to what extent our results are generalizable to reports of the Lareb database as well as to other pharmacovigilance centers. Healthcare professionals as well as patients report because of the severity of the reaction and wanting to contribute to medical knowledge [30]. Patients also report because they felt their complaints were not taken seriously elsewhere or because they already reported the ADR to a healthcare professional with no result [30]. Unfortunately, we have no data on motives for reporting in the Lareb database. Regarding the generalizability, the overall characteristics, male–female ratio and reported ADR (based on System Organ Class classification) of the included reports are in line with previous studies [12, 15, 16, 19, 22, 30–35]. Not surprisingly, our study set concerned 33.5% serious reports, which is a higher percentage than the average percentage of serious reports present in the Lareb database (average of 20% serious healthcare professional reports and 18% patient reports, from 2013 to 2015) [36]. Finally, we do not know to what extent the healthcare professional and patient discussed the case and whether this had an influence on the level of information reporting. Due to these biases, results should be generalized with caution.

Some methodological issues have to be addressed. In order to analyze the level of reporting of clinical information, we used the ClinDoc tool [27]. This tool determines which information is relevant for a case and then assesses whether relevant information has been reported completely. Even though we used a standardized method of assessment, the level of clinical information remains a somewhat subjective measure, but using a structured approach was better than subjectively comparing reports of patients and healthcare professionals. For the present study, we tried to minimize variations between assessors by training assessors how to use the tool. Furthermore, each report was scored by two assessors individually and differences between domain scores were discussed until agreement was reached. In order to keep assessors ‘blind’ about the type of reporter (patient or healthcare professional), we had to remove some identifying information.

Reports by patients and healthcare professionals reflect their own experiences and perceptions of the ADR. The present study specifically compared the level of reporting of clinical information. We did not capture all possible information that can be reported in our study. Others, for example, showed that patients report more about the impact of the ADR on their daily life compared with healthcare professionals [19, 20, 37, 38]. This information is also valuable for pharmacovigilance practice. In our view, reports of both patients and healthcare professionals can contribute to optimal pharmacovigilance.

5 Conclusion

In a unique study of cases of ADRs reported by patients and healthcare professionals, we found that patients report clinical information at a similar level as their healthcare professional. For an optimal pharmacovigilance, both healthcare professionals and patient should be encouraged to report.

References

World Health Organization. The importance of pharmacovigilance: safety monitoring of medicinal products. 2002 [cited 2016 Dec 1]. http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js4893e/.

US Food and Drug Administration. FDA adverse events reporting system (FAERS). 2016. [cited 2016 Feb 25]. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/UCM082196.

Ishiguro C, Hall M, Neyarapally GA, Dal PG. Post-market drug safety evidence sources: an analysis of FDA drug safety communications. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(10):1134–6.

van Hunsel F, Härmark L, Pal S, Olsson S, van Grootheest K. Experiences with adverse drug reaction reporting by patients; an 11-country survey. Drug Saf. 2012;35(1):45–60.

The EU pharmacovigilance system. 2012 [cited 2016 Feb 17]. http://ec.europa.eu/health/human-use/pharmacovigilance/index_en.htm.

Inch J, Watson MC, Anakwe-Umeh S. Patient versus healthcare professional spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2012;35(10):807–18.

Harmark L, van HF, Grundmark B. ADR reporting by the general public: lessons learnt from the Dutch and Swedish systems. Drug Saf. 2015;38(4):337–47.

Hazell L, Cornelius V, Hannaford P, Shakir S, Avery AJ. How do patients contribute to signal detection? A retrospective analysis of spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions in the UK’s Yellow Card Scheme. Drug Saf. 2013;36(3):199–206.

van Hunsel F. The contribution of direct patient reporting to pharmacovigilance. Thesis, University of Groningen, The Netherlands; 2011.

Inacio P, Cavaco A, Airaksinen M. The value of patient reporting to the pharmacovigilance system: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;83(2):227–46.

Edwards IR, Aronson JK. Adverse drug reactions: definitions, diagnosis, and management. Lancet. 2000;356(9237):1255–9.

Aagaard L, Hansen E. Consumers’ reports of suspected adverse drug reactions volunteered to a consumer magazine. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;69(3):317–8.

Chebane L, Abadie D, Bagheri H, Durrie G, Montastruc JL. Patient reporting of adverse drug reactions: experience of Toulouse Regional Pharmacovigilance Center (abstract ISoP 2012). Drug Saf. 2012;35(942):942.

Clothier H, Selvaraj G, Easton M, Lewis G, Crawford N, Buttery J. Consumer reporting of adverse events following immunization. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2014;10(12):3726–30.

de Langen J, van Hunsel F, Passier A, de Jong-van den Berg LTW, van Grootheest AC. Adverse drug reaction reporting by patients in the Netherlands, three years of experience. Drug Saf. 2008;31(6):515–24.

Durrieu G, Palmaro A, Pourcel L, Caillet C, Faucher A, Jacquet A, et al. First French experience of ADR reporting by patients after a mass immunization campaign with influenza A (H1N1) pandemic vaccines: a comparison of reports submitted by patients and healthcare professionals. Drug Saf. 2012;35(10):845–54.

Jansson K, Ekbom Y, Sjölin-Forsberg G. Basic conditions for consumer reporting of adverse drug reactions in Sweden—a pilot study (abstract 28). Drug Saf. 2006;29(10):938.

Leone R, Moretti U, D’Incau P, Conforti A, Magro L, Lora R, et al. Effect of pharmacist involvement on patient reporting of adverse drug reactions: first Italian study. Drug Saf. 2013;36(4):267–76.

McLernon DJ, Bond CM, Hannaford PC, Watson MC, Lee AJ, Hazell L, et al. Adverse drug reaction reporting in the UK: a retrospective observational comparison of yellow card reports submitted by patients and healthcare professionals. Drug Saf. 2010;33(9):775–88.

Medawar C, Herxheimer A. A comparison of adverse drug reaction reports from professionals and users, relating to risk of dependence and suicidal behaviour with paroxetine. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2003;16:5–19.

Rolfes L, van Hunsel F, Wilkes S, van Grootheest K, van Puijenbroek E. Adverse drug reaction reports of patients and healthcare professionals–differences in reported information. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(2):152–8.

van Grootheest A, Passier J, van Puijenbroek E. Direct reporting of side effects by the patient: favourable experience in the first year (article in Dutch). Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2005;149(10):529–33.

van Hunsel F, Passier A, van Grootheest AC. Comparing patients’ and healthcare professionals’ ADR reports after media attention. The broadcast of a Dutch television programme about the benefits and risks of statins as an example. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67(5):558–64.

Vilhelmsson A, Svensson T, Meeuwisse A, Carlsten A. What can we learn from consumer reports on psychiatric adverse drug reactions with antidepressant medication? Experiences from reports to a consumer association. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2011;11:16.

Netherlands Pharmacovigilance Centre Lareb. Highlights. 2015 [cited 2016 Sep 2]. http://www.lareb.nl/getmedia/412dcc1d-13fb-4b9d-83a9-a5844b6e1b79/highlights-bcl-2015-NL_1.pdf.

MedDRA®. Medical dictionary for regulatory activities. 2016. http://www.meddra.org.

Oosterhuis I, Rolfes L, Ekhart C, Muller-Hansma A, Härmark L. Development and validity testing of a clinical documentation-tool to assess individual case safety reports in an international setting (abstract 716). PDS. 2016;25(Suppl. 3):417.

WEB-RADR: recognising adverse drug reactions. 2016 [cited 2015 Aug 1]. http://www.web-radr.eu.

Counsel for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS). Reporting adverse drug reactions; definitions of terms and criteria for their use. 1999. http://www.cioms.ch/publications/reporting_adverse_drug.pdf.

van Hunsel F, van der Welle C, Passier A, van Puijenbroek E, van Grootheest K. Motives for reporting adverse drug reactions by patient-reporters in the Netherlands. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66(11):1143–50.

Rolfes L, van Hunsel F, van Grootheest K, van Puijenbroek E. Feedback for patients reporting adverse drug reactions; satisfaction and expectations. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2015;14(5):625–32.

Aagaard L, Nielsen LH, Hansen EH. Consumer reporting of adverse drug reactions: a retrospective analysis of the Danish adverse drug reaction database from 2004 to 2006. Drug Saf. 2009;32(11):1067–74.

Manso G, Salgueiro M, Jimeno F, Aguirre C, Garcia M, Etxebarria A, et al. Preliminary results for reporting of problems associated with medications in Spain. The yo notifico (I notify) project. (abstract ISP3541-41). Drug Saf. 2013;36(793):951.

Parretta E, Rafaniello C, Magro L, Coggiola PA, Sportiello L, Ferrajolo C, et al. Improvement of patient adverse drug reaction reporting through a community pharmacist-based intervention in the Campania region of Italy. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(Suppl 1):S21–9.

Povlsen K, Michan L, Frederiksen M, Kornholt J, Harder H. Characteristics and contribution of consumer reports of adverse drug reactions: experience from Denmark during the last decade (abstract P082). Drug Saf. 2012;35(10):877–970.

Netherlands Pharmacovigilance Centre Lareb. Annual statistics Lareb database (personal communication). 2016.

Rolfes L, van Hunsel F, Taxis K, van Puijenbroek E. The impact of experiencing adverse drug reaction on the patient’s quality of life: a retrospective cross-sectional study in the Netherlands. Drug Saf. 2016. (Epub ahead of print).

Vilhelmsson A, Svensson T, Meeuwisse A, Carlsten A. Experiences from consumer reports on psychiatric adverse drug reactions with antidepressant medication: a qualitative study of reports to a consumer association. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2012;13:19.

Additional Contributions

We acknowledge our colleges of Lareb who helped us with the scoring of all reports included in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Leàn Rolfes, Florence van Hunsel, Laura van der Linden, Katja Taxis and Eugène van Puijenbroek declare that they have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to the content of this study.

Funding/support

No sources of funding were used to assist in the preparation of this study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rolfes, L., van Hunsel, F., van der Linden, L. et al. The Quality of Clinical Information in Adverse Drug Reaction Reports by Patients and Healthcare Professionals: A Retrospective Comparative Analysis. Drug Saf 40, 607–614 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-017-0530-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40264-017-0530-5