Abstract

Background

Alirocumab, a human monoclonal antibody, inhibits proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) to significantly reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels; pharmacokinetics (PK) are governed by non-linear, target-mediated drug disposition (TMDD).

Objectives

We aimed to develop and qualify a population PK (PopPK) model to characterize the PK profile of alirocumab, evaluate the impact of covariates on alirocumab PK and on individual patient exposures, and estimate individual predicted concentrations for a subsequent PK/pharmacodynamic (PD) analysis.

Methods

Data from 13 phase I–III trials of 2799 healthy volunteers or patients with hypercholesterolemia treated with intravenous or subcutaneous alirocumab (13,717 alirocumab concentrations) were included; a Michaelis–Menten approximation of the TMDD model was used to estimate PK parameters and exposures. The final model comprised two compartments with first-order absorption. Elimination from the central compartment was described by linear (CLL) and non-linear Michaelis–Menten clearance (Vm and Km). The model was validated using visual predictive check and bootstrap methods. Patient exposures to alirocumab were computed using individual PK parameters.

Results

The PopPK model was well-qualified, with the majority of observed alirocumab concentrations in the 2.5th–97.5th predicted percentiles. Covariates responsible for interindividual variability were identified. Body weight and concomitant statin administration impacted CLL, whereas time-varying free PCSK9 concentrations and age affected Km and peripheral distribution volume (V3), respectively. No covariates were clinically meaningful, therefore no dose adjustments were needed.

Conclusions

The model explained the between-subject variability, quantified the impact of covariates, and, finally, predicted alirocumab concentrations (subsequently used in a PopPK/PD model, see Part II) and individual exposures.

Similar content being viewed by others

The population pharmacokinetic model successfully allowed the prediction of the pharmacokinetic properties of alirocumab in the target population, as well as individual exposures. |

Covariates that impacted on the interindividual variability of alirocumab were identified, with the most important effect being the impact of body weight and coadministration of statins on the linear clearance rate. |

The impact of covariates did not have any clinically significant effect. |

1 Introduction

High levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) are a causative risk factor for cardiovascular disease (CVD), a disease that is recognized as a leading cause of premature mortality worldwide [1, 2]. Statin monotherapy is widely used for the treatment of hypercholesterolemia; however, statin intolerance and the inability to achieve target cholesterol levels with statin therapy alone has highlighted a need for novel therapeutic agents [1]. The proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitor alirocumab has been approved by the US FDA as an adjunct to diet and maximally tolerated statin therapy for the treatment of adults with clinical atherosclerotic CVD or heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) who require additional LDL-C lowering. Furthermore, the European Medicines Agency has approved alirocumab for those with either heterozygous FH or non-FH and mixed dyslipidemia, as an adjunct to diet and in combination with a statin ± other lipid-lowering therapies (LLTs) in patients unable to reach LDL-C goals with the maximally tolerated dose of a statin, who are statin-intolerant, or for whom a statin is contraindicated [3, 4].

In humans, PCSK9 (a member of the subtilisin family of serine proteases) is primarily expressed in the liver [5, 6], where it binds to low-density lipoprotein receptors (LDL-R) and targets them for internalization and degradation. Alirocumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody, prevents LDL-R degradation by binding to and inhibiting PCSK9, resulting in increased LDL-R levels on the surface of hepatocytes, and increased LDL-C clearance [7]. Clinical studies have shown that treatment with alirocumab reduces LDL-C levels by up to 61% when added to background statins [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15].

The pharmacokinetics (PK) of alirocumab are described by parallel linear and non-linear processes; non-linear processes are governed by PCSK9 production, alirocumab–PCSK9 complex formation, and lysosomal degradation of the alirocumab–PCSK9 complex. Therefore, alirocumab is characterized by target-mediated drug disposition (TMDD) with kinetics that are related to its mechanism of action. PCSK9, and thereby the alirocumab–PCSK9 complex, is involved in an endosomal-lysosomal transport and degradation process by the same mechanism as for the PCSK9–LDL-R complex. At low concentrations, alirocumab is eliminated through its binding to PCSK9 via lysosomal degradation [16], while at high alirocumab concentrations, PSCK9 becomes saturated and alirocumab elimination occurs via a linear, non-saturable proteolytic pathway. The kinetics of both alirocumab and PCSK9 have been described by a population PK (PopPK) model of alirocumab that was developed by taking into account the mechanistic TMDD process. The model accurately predicted both alirocumab and total PCSK9 concentrations in patients and healthy subjects, and revealed a significant relationship between linear alirocumab clearance and statin coadministration [17], demonstrating the utility of PopPK–TMDD models in characterizing the PK profile of alirocumab in its target population.

In this analysis, we present a PopPK model that was developed to characterize the PK of alirocumab in both healthy individuals and patients with FH and non-FH, based on pooled data from phase I–III clinical studies. Potential covariates affecting alirocumab PK explored include PCSK9 concentrations, patient/subject demographics, coadministration of LLTs, antidrug antibody (ADA) status, disease status (FH vs. non-FH), administration site, injection device, relevant biologic constants, and renal function. The effect of these covariates were investigated using a Michaelis–Menten approximation of a TMDD model for alirocumab so that individual patient PK parameters and exposures [area under the concentration–time curve (AUCτ) and maximum concentration (Cmax)] could be estimated. Ultimately, the individual predicted concentrations were used as input values for a subsequent PopPK/pharmacodynamic (PD) study [18].

2 Methods

2.1 Clinical Study Design

Data were derived from phase I (NCT01026597, NCT01074372, NCT01161082 [19], NCT01448317, and NCT01723735), phase II (NCT01288443, NCT01288469 [20, 21], NCT01812707, and NCT01576484), and phase III (NCT01644188 [ODYSSEY COMBO II] [10], NCT01644474 [ODYSSEY MONO] [8], NCT01623115 [ODYSSEY FH I] [9], and NCT01507831 [ODYSSEY LONG TERM] [11]) clinical studies. The dataset was composed of healthy individuals as well as patients with FH and non-FH.

Across the studies, alirocumab was administered either as a single subcutaneous dose or multiple subcutaneous doses, except for one phase I study that used a single intravenous dose. Alirocumab doses ranged from 0.3 to 12 mg/kg for the intravenous study, and from 50 to 300 mg for the subcutaneous studies. Doses were administered every 2 weeks or every 4 weeks over a period of up to 104 weeks; however, the current analyses used PK data obtained up to 24 weeks. A summary of alirocumab doses and dosing regimens of the clinical studies included in this analysis are presented in Table 1.

These studies were performed in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and all applicable amendments by the World Medical Assemblies, and the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

2.2 Bioanalysis

Assay methods for total alirocumab and free and total PCSK9 were previously described [22], as were methods for anti-alirocumab antibodies [23]. Further details of assay methods are provided in the electronic supplementary material.

2.3 Pharmacokinetic Exclusion Criteria

Patients and healthy individuals receiving placebo treatment were excluded from the overall database of randomized and treated subjects. For subjects treated with alirocumab, data were excluded due to missing alirocumab concentrations, missing dosing dates and times, or values below the lower limit of quantification. Missing covariate values were replaced by the previous values from the same individual [last observation carried forward (LOCF)]. However, missing data for ADA status were not replaced using the LOCF imputation, but instead were always considered missing. In addition, all baseline values for ADAs were set to a negative ADA status.

2.4 Population Model Development

The PopPK analysis was performed using the NONMEM® computer program (version 7.2; ICON Development Solutions, San Antonio, TX, USA) running on a LINUX cluster of multiprocessor computers [24]. All runs were performed using the first-order conditional estimation with interaction method.

2.5 Pharmacostatistical Model Development

As a first step, an accurate screening for outliers was performed on the analysis dataset using a preliminary, non-qualified model. Once outliers were detected and, if appropriate, excluded from the database, the preliminary model was used as a basis for building the pharmacostatistical model. Several potential structural models were investigated [one or two compartments, first- or zero-order absorption constant, linear or Michaelis–Menten elimination or a combination of both, and a TMDD model with a quasi-steady-state (QSS) approximation]. In addition, several variations from the preliminary model were tested by adding or removing interindividual variability terms, or testing additive or proportional variability models.

2.6 Covariate Screening

The relationship between the individual estimates and the following covariates was investigated: demographic characteristics, such as body weight, body mass index (BMI), age, sex, race, renal function (evaluated by creatinine clearance [calculated using the Cockcroft–Gault formula] and the estimated glomerular filtration rate [calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation]), and albumin concentrations. In addition, the coadministration of other LLTs, free and total PCSK9 concentrations in serum, type of disease (FH or non-FH), presence of ADAs, type of injection device (prefilled syringe and vials or autoinjector device), and the site of injection were also included as covariates. A complete list of covariates investigated, along with relevant codings, is given in the electronic supplementary Methods. When available, the time-varying values of covariates were used in addition to baseline values. The influence of continuous covariates was evaluated on model parameters using the following coding:

-

TVPARAM = θ(1) + θ(x) × COV

-

TVPARAM = θ(1) + θ(x) × (COV/Median COV)

-

TVPARAM = θ(1) + θ(x) × (COV − Median COV)

-

TVPARAM = θ(1) × (COV/Median COV) ** θ(x)

-

TVPARAM = θ(1) × COV/(θ(x) + COV)

where TVPARAM is the typical value (population parameter) and COV is the value of the considered continuous covariate.

To evaluate the potential influence of categorical covariates (CAT) on the model parameters, the following coding was used:

-

TVPARAM = θ(1) × CAT + θ(x) × (1 − CAT)

-

TVPARAM = θ(1) + θ(x) × CAT

-

TVPARAM = θ(1) × θ(4)**CAT

The selected covariates were added individually to the model in a forward selection method and tested for statistical significance. Covariates providing a significant change (p < 0.05, log likelihood ratio test) in the objective function value (OFV) were retained. After each covariate–parameter relationship tested, the best model in terms of OFV (and quality criteria) was selected for the next step. A backward deletion was then performed to assess the covariate parameter relationships. Only covariates associated with a significant change in the OFV, with a p value < 0.001, were retained in the final model. The population parameters were then re-estimated considering the relationship with the covariates. The impact of covariate inclusion on interindividual variability was measured by the percentage of decrease in the variance of each model parameter ([ω2before covariate inclusion − ω2after covariate inclusion]/ω2before covariate inclusion). Statistically significant covariates were also assessed in terms of biological plausibility and clinical implications.

2.7 Model Qualification

Before qualification, model verification was performed by examination of the goodness-of-fit plots and estimation of several quality criteria, such as bias, precision, or average fold error. Goodness-of-fit plots and quality criteria were provided for both the pharmacostatistical model and final model to allow a comparison. Validation of the predictive ability of the PopPK model was performed using different approaches, including examination of individual concentration versus time curves, visual predictive check, and bootstrap methods.

2.8 Computation of Individual Parameters

Once the model was qualified, model parameters were used to compute the individual alirocumab PK parameter estimates for phase III patients. Steady-state exposure variables (Cmax and AUCτ) were then derived on weeks 22–24 (or weeks 10–12 if not available, as steady state was already reached at this time). Descriptive statistics were provided for each dose administered in the phase III studies (75 or 150 mg every 2 weeks) and by covariates of interest.

3 Results

3.1 Final Population Pharmacokinetic Model

Data from 2799 individuals, consisting of 13,817 alirocumab concentrations over time, were included in this PopPK analysis. The exclusion of 100 outlier concentration–time points resulted in a total dataset of 13,717 samples.

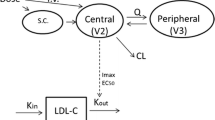

The pharmacostatistical model (refer to Fig. 1 for schematic) was a two-compartment model with an absorption constant (Ka, 1/h), characterizing the first-order absorption process from the depot to the central compartment, described by an apparent distribution volume (V2, L). The peripheral compartment was related to the central compartment by an intercompartmental clearance (Q, L/h) and described by an apparent distribution volume (V3, L). The elimination was characterized by a first-order process described as an apparent linear clearance (CLL, L/h) and a parallel non-linear process described by the two Michaelis–Menten parameters, Vm (mg/h) and Km (mg/L). Lag time (LAG) and the bioavailability factor (F) completed the set of fixed-effect model parameters (θs).

Schematic of the pharmacostatistical model, a two-compartment model characterized by a first-order absorption process from the depot to the central compartment. The first-order absorption process was described by an absorption constant. The two compartments are represented by a distribution volume (V2 and V3) and are linked by an intercompartmental clearance. Two elimination processes from the central compartment are possible: a linear process, represented by linear elimination clearance, and a parallel non-linear process, represented by the two Michaelis–Menten parameters (Vm and Km). A lag-time and the bioavailability factor associated with subcutaneous administration of alirocumab complete the set of fixed-effect model parameters, θs. Ka absorption constant, V2 distribution volume from the depot to the central compartment, V3 distribution volume from the central to peripheral compartments, Q intercompartmental clearance, CLL linear clearance, LAG lag time, F bioavailability factor, SC subcutaneous

The interindividual variability was modeled through an exponential error model for all parameters except LAG, Q, Ka, and Vm, for which no interindividual term could be provided. A combined proportional plus additive error model was used to model the residual variability. The influence of the estimation of covariance between ηs within an ω-block was evaluated on the structural model, and the difference in OFV (ΔOFV) was significant (ΔOFV = 76.9) for the block Km/V3. After examination of the goodness-of-fit plots (left part of electronic supplementary Figs. 1–4) and computation of quality criteria (upper part of electronic supplementary Table 1), this model was considered the final pharmacostatistical model (Table 2).

After extensive covariate screening, the final PopPK model included four covariates (Table 2): two [body weight (WT) and statin coadministration (STATIN)] on the linear elimination clearance (L/h), one [time-varying free PCSK9 (FPCSK9) levels] on the Michaelis–Menten parameter Km, and one [subject/patient age (AGE)] on the volume of distribution of the peripheral compartment V3, according to the following equations (TV = typical value; COVx = coefficient for the covariate effect):

-

CLL = TVCLL + COV1 × (WT − 82.9) + COV2 × STATIN

-

Km = TVKm + COV3 × (FPCSK9/72.9)

-

V3 = TVV3 × (AGE/60) COV4

After covariate inclusion, the interindividual terms were decreased for CLL, Km, and V3 (42.3, 11.6, and 51.3% decrease, respectively), confirming the impact of covariates (see Table 2). For F, the interindividual variability estimated in the logit space was 103%; back calculation in normal space around the median of individual values (0.866) gave 0.674 < F < 0.913 (5th–95th percentiles).

The quality of the final model was graphically evaluated using goodness-of-fit plots (right part of electronic supplementary Figs. 1–4) and the quality criteria (lower part of electronic supplementary Table 1). The robustness of the final model and the accuracy of parameter estimates (standard error computation) were validated using a bootstrap and a visual predictive check method. The parameter values of the final model were very close to the median bootstrap values (estimated on 381 successfully minimized runs obtained from the 1000 launched runs) and were included in the 95% confidence interval computed from the bootstrap (electronic supplementary Table 2). Using visual predictive check, a large majority of the observed concentrations were within the range of the 2.5th to 97.5th predicted percentiles (Fig. 2). This represents a good qualification of the PopPK model developed in the current analysis.

Visual predictive check of results per study. Linear scale. Dark blue dots represent observations, solid red line represents median of observations, solid dashed lines represent 5th and 95th percentiles of observations, pink and blue areas represent confidence intervals of the median and 5th and 95th percentiles of predictions, respectively. STUD study

3.2 Impact of Covariates on Model Parameters

Body weight and coadministration of statins were found to impact alirocumab CLL significantly. CLL decreased by 78% in subjects weighing 50 kg, and increased by 40% in subjects weighing 100 kg, compared with a typical patient weighing 82.9 kg (median body weight). In a patient of median body weight, CLL was increased by 52% when statins were coadministered with alirocumab.

The impact of time-varying free PCSK9 concentrations on Km was also significant. For the 5th (0 ng/mL) and 95th (392 ng/mL) percentiles of time-varying FPCSK9 levels in the study population, Km was 7.73 ng/mL and 4.82 ng/mL, respectively. Although age was also identified as a significant covariate impacting peripheral volume of distribution in the PopPK model, the effect of age was minimal. The peripheral volume of distribution increased from 2.79 L for a patient aged 60 years, to 2.86 L for a patient aged 65 years and 2.99 L for a patient aged 75 years.

3.3 Impact of Covariates on Alirocumab Exposure

The impact of the four significant covariates included in the final PopPK model (body weight, coadministration of statin, age, and time-varying FPCSK9 concentrations) was evaluated on alirocumab steady-state exposure, as shown in Fig. 3 (AUC336) and Fig. 4 (Cmax). Increased body weight was associated with reduced alirocumab exposure for both the 75 and 150 mg every 2 weeks dosing regimens. In patients weighing more than 100 kg, alirocumab AUC336 after administration of 75 and 150 mg doses every 2 weeks decreased by 29 and 36%, respectively, compared with patients weighing between 50 and 100 kg (AUC336 = 2170 mg·h/L). In a patient of median body weight, coadministration of a statin resulted in a 28–29% decrease in AUC336 after both the 75 and 150 mg doses compared with patients receiving monotherapy. The impact of FPCSK9 concentrations at baseline only slightly impacted alirocumab exposure at steady state. Alirocumab exposure after 75 and 150 mg every 2 weeks was 9 and 19% lower, respectively, for patients whose FPCSK9 baseline concentrations were above the median baseline concentration (283 ng/mL) than those with baseline concentrations below the median. Patient age was associated with small differences in alirocumab steady-state exposure at both the 75 and 150 mg every 2 weeks dosing regimens. There was an 8% increase in alirocumab exposure in patients between 65 and 75 years of age compared with those who were 65 years of age or younger. Alirocumab exposure also increased by 10–36% in patients older than 75 years of age compared with patients younger than 65 years of age.

Overview of covariate impact on alirocumab steady-state exposures in patients from phase III trials. aNumber of patients in the 75/150 mg dose category. Blue diamonds represent the median of the 75 mg dose category, red diamonds represent the median of the 150 mg dose category. AUC area under the concentration–time curve, BMI body mass index, CI confidence interval, PCSK9 proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9

Box plot of Cmax values for patients included in the phase III study as a function of several covariates. aNumber of patients in the 75 mg/150 mg dose category. Blue diamonds represent the median of the 75 mg dose category, red diamonds represent the median of the 150 mg dose category. BMI body mass index, CI confidence interval, Cmax maximum concentration, PCSK9 proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9

Covariates of interest not identified as significant in the PopPK model included race, sex, renal function, BMI, and presence of ADAs (Figs. 2, 3).

4 Discussion

A two-compartment Michaelis–Menten PopPK model, parameterized with a first-order absorption process and two elimination processes (one linear and one non-linear), was developed and qualified in a dataset of 2799 healthy subjects or patients with hypercholesterolemia enrolled in phase I, II, and III studies. This analysis showed that the PK of alirocumab can be accurately predicted using this model. Agreement between model-predicted and observed serum concentrations was noted, allowing characterization of alirocumab PK properties in the target population as well as individual exposures.

This model also enabled identification of covariates that explained part of the interindividual variability of the compound. CLL was related to body weight and statin coadministration, whereas Km was related to free time-varying PCSK9 concentrations in serum, and V3 was related to age. The greater effect of body weight on alirocumab steady-state exposure at 150 mg every 2 weeks, compared with 75 mg every 2 weeks, is consistent with the observation that body weight only impacts the linear part of the clearance, which is prominent at the highest alirocumab exposures when the target mediated clearance is saturated (Fig. 5). Statins were anticipated to impact non-linear clearance of alirocumab through the upregulation of PCSK9 concentrations that is typically observed with statin therapy [25]. Conversely, in this population analysis, the effect of statins was observed on the CLL. Similar observations have been reported for evolocumab, another anti-PCSK9 monoclonal antibody, where statins significantly increased evolocumab clearance [26]. We also recently showed a significant relationship between CLL and statin coadministration [17], resulting in a 1.27-fold higher CLL when statins were coadministered. We proposed two hypotheses to explain these findings. The first related to the upregulation of PCSK9 by statins, as previously reported [25, 27]; however, there was no significant relationship between any model parameter and baseline PCSK9 levels. The second hypothesis was linked to previous findings that showed that statins have proangiogenic effects, via the acceleration of re-endothelialization and the mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells [28, 29]. Indeed, the main catabolic pathway for monoclonal antibodies representing the CLL occurs via the reticuloendothelial system [30]. The proangiogenic effects of statins was suggested to result in a significantly higher CLL. As alirocumab is eliminated through target-mediated clearance, the concentration of FPCSK9 was expected to influence alirocumab PK. In support of this, the time-varying FPCSK9 concentration was identified as a significant covariate affecting alirocumab PK, through its impact on the Michaelis–Menten constant in the PopPK model. Although age was a significant covariate, the impact of the inclusion of this covariate on V3 was very limited, translating into a small to no effect on alirocumab exposure. This limited impact of age on post hoc assessment of alirocumab exposure remained within the exposure ranges observed across clinical studies of alirocumab [16, 22, 31]. In addition, this did not translate into clinically meaningful differences in efficacy and safety profiles assessed across all age categories. Therefore, no dose adjustments are recommended in elderly patients.

Dependence of predicted total, linear, and non-linear clearance on alirocumab concentration in patients coadministered with statins from phase III studies. Cmax maximum change from baseline, Ctrough difference between baseline and value before next alirocumab dose, FPCSK9 time-varying free proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9, KM Michaelis–Menten parameter

Consistent with other monoclonal antibodies, the large size of the alirocumab molecule is expected to prevent filtration through the glomerulus and, consequently, elimination via the renal route is expected to be insignificant [32,33,34]. Indeed, renal function was not identified as a significant covariate influencing alirocumab population parameters in this analysis. Differences in body weight are also likely to account for the small differences in sex, another non-significant covariate, on alirocumab steady-state exposure observed in this study.

One limitation of this model is that it is based on a Michaelis–Menten approximation of a TMDD model. A more mechanistic TMDD model, such as a QSS approximation of a model, could be used to characterize the functionality of alirocumab and PCSK9 kinetics. Separate from this analysis, a TMDD-QSS model has been developed and qualified [17]. In such a model, both alirocumab concentration and PCSK9 total concentrations are used as dependent variables; the consequence is that even if the global quality criteria computed for this model (for alirocumab and PCSK9) are fairly good overall, the quality of the estimation for alirocumab concentrations remained lower than the one obtained using the Michaelis–Menten approximation, with an average fold error of 1.21 for TMDD–Michaelis–Menten and 1.35 for TMDD–QSS. This debase for alirocumab concentrations was expected as the TMDD–QSS model must fit both alirocumab and PCSK9 concentrations in a single step. It should also be mentioned that model stability was better with the Michaelis–Menten approximation, leading to easier exploration of the covariate/parameter relations. Moreover, the duration of the runs was at least two times longer for the QSS approximation. As the main objectives of this work were to explain the between-patient variability of alirocumab, and to provide the best individual estimates for a PK/PD analysis, the Michaelis–Menten approximation of the TMDD model was finally retained.

5 Conclusions

Alirocumab PK can best be described as non-linear, with target-mediated clearance, although the deviation from linearity is modest. The PopPK model presented here was well-qualified and, although not fully mechanistic, allowed the characterization of alirocumab PK properties in its target population, as well as the estimation of alirocumab exposure in individual patients. Four covariates were found to be significant and were retained in the final PopPK model, i.e. body weight, coadministration of statin, age, and time-varying PCSK9 concentrations. However, their limited impact on exposure did not translate into any clinically meaningful difference in efficacy or safety, in part because dose uptitration accommodates for any potential difference in exposure. Therefore, no adjustments are recommended according to patient body weight, age, or concomitant statin use. The alirocumab concentrations predicted by this model have been used to build a PopPK/PD model (see Part II of this series) to facilitate further characterization of the PK/PD of alirocumab and the effect of LDL-C reduction [18].

References

Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, et al. ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: the task force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;2016:2999–3058.

Yadav K, Sharma M, Ferdinand KC. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors: present perspectives and future horizons. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;26(10):853–62.

Sanofi. Praluent prescribing information (US). 2015. http://products.sanofi.us/praluent/praluent.pdf. Accessed 19 July 2016.

Sanofi. Praluent Summary of Product Characteristics. 2015. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/003882/WC500194521.pdf. Accessed 19 July 2016.

Zaid A, Roubtsova A, Essalmani R, et al. Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9): hepatocyte-specific low-density lipoprotein receptor degradation and critical role in mouse liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2008;48(2):646–54.

Seidah NG, Benjannet S, Wickham L, et al. The secretory proprotein convertase neural apoptosis-regulated convertase 1 (NARC-1): liver regeneration and neuronal differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(3):928–33.

Cariou B, Le May C, Costet P. Clinical aspects of PCSK9. Atherosclerosis. 2011;216(2):258–65.

Roth EM, Taskinen MR, Ginsberg HN, et al. Monotherapy with the PCSK9 inhibitor alirocumab versus ezetimibe in patients with hypercholesterolemia: results of a 24 week, double-blind, randomized Phase 3 trial. Int J Cardiol. 2014;176(1):55–61.

Kastelein JJ, Ginsberg HN, Langslet G, et al. ODYSSEY FH I and FH II: 78 week results with alirocumab treatment in 735 patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(43):2996–3003.

Cannon CP, Cariou B, Blom D, et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in high cardiovascular risk patients with inadequately controlled hypercholesterolaemia on maximally tolerated doses of statins: the ODYSSEY COMBO II randomized controlled trial. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(19):1186–94.

Robinson JG, Farnier M, Krempf M, et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in reducing lipids and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(16):1489–99.

Kereiakes DJ, Robinson JG, Cannon CP, et al. Efficacy and safety of the proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitor alirocumab among high cardiovascular risk patients on maximally tolerated statin therapy: the ODYSSEY COMBO I study. Am Heart J. 2015;169(6):906-15.e13.

Farnier M, Jones P, Severance R, et al. Efficacy and safety of adding alirocumab to rosuvastatin versus adding ezetimibe or doubling the rosuvastatin dose in high cardiovascular-risk patients: the ODYSSEY OPTIONS II randomized trial. Atherosclerosis. 2016;244:138–46.

Bays H, Gaudet D, Weiss R, et al. Alirocumab as add-on to atorvastatin versus other lipid treatment strategies: ODYSSEY OPTIONS I randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(8):3140–8.

Ginsberg HN, Rader DJ, Raal FJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of alirocumab in patients with heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia and LDL-C of 160 mg/dl or higher. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2016;30(5):473–83.

European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment Report (EPAR) WC500194524. 2015. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/003882/WC500194524.pdf. Accessed Oct 2016.

Djebli N, Martinez JM, Lohan L, et al. Target-mediated drug disposition population pharmacokinetics model of alirocumab in healthy volunteers and patients: pooled analysis of randomized phase I/II/III studies. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2017;56(10):1155–71.

Nicolas X, Djebli N, Rauch C, et al. Population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic analysis of alirocuamb in healthy volunteers or hypercholesterolemic subjects using an indirect response model to predict low-density lipoprotein cholesterol lowering: Support for a Biologics License Application submission: Part II. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-018-0670-5.

Stein EA, Mellis S, Yancopoulos GD, et al. Effect of a monoclonal antibody to PCSK9 on LDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(12):1108–18.

Koren MJ, Kereiakes D, Pourfarzib R, et al. Effect of PCSK9 inhibition by alirocumab on lipoprotein particle concentrations determined by nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(11):e002224.

Roth EM, McKenney JM, Hanotin C, et al. Atorvastatin with or without an antibody to PCSK9 in primary hypercholesterolemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(20):1891–900.

Rey J, Poitiers F, Paehler T, et al. Relationship between low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, free proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9, and alirocumab levels after different lipid-lowering strategies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(6):e003323.

Roth EM, Goldberg AC, Catapano AL, et al. Antidrug antibodies in patients treated with alirocumab. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(16):1589–90.

Speth H. A Linux cluster for population pharmacokinetic analyses. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;42(3):189–90.

Guo YL, Zhang W, Li JJ. PCSK9 and lipid lowering drugs. Clin Chim Acta. 2014;437:66–71.

Gibbs JP, Doshi S, Kuchimanchi M, et al. Impact of target-mediated elimination on the dose and regimen of evolocumab, a human monoclonal antibody against proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9). J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;57(5):616–26.

Mayne J, Dewpura T, Raymond A, et al. Plasma PCSK9 levels are significantly modified by statins and fibrates in humans. Lipids Health Dis. 2008;7:22.

Walter DH, Rittig K, Bahlmann FH, et al. Statin therapy accelerates reendothelialization: a novel effect involving mobilization and incorporation of bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells. Circulation. 2002;105(25):3017–24.

Walter DH, Zeiher AM, Dimmeler S. Effects of statins on endothelium and their contribution to neovascularization by mobilization of endothelial progenitor cells. Coron Artery Dis. 2004;15(5):235–42.

Shi S. Biologics: an update and challenge of their pharmacokinetics. Curr Drug Metab. 2014;15(3):271–90.

Lunven C, Paehler T, Poitiers F, et al. A randomized study of the relative pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and safety of alirocumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody to PCSK9, after single subcutaneous administration at three different injection sites in healthy subjects. Cardiovasc Ther. 2014;32(6):297–301.

Wang W, Wang EQ, Balthasar JP. Monoclonal antibody pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2008;84(5):548–58.

Ryman JT, Meibohm B. Pharmacokinetics of Monoclonal Antibodies. CPT Pharmacomet Syst Pharmacol. 2017;6(9):576–88.

Berdeja J, Jagannath S, Zonder J, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of elotuzumab combined with lenalidomide and dexamethasone in patients with multiple myeloma and various levels of renal impairment: results of a phase Ib study. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2016;16(3):129–38.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants, their families, and all investigators involved in the studies used in this analysis. The following people from the study sponsors reviewed and provided editorial comments on the manuscript: Carol Hudson and Robert Pordy (Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.), and Corinne Hanotin and Michael Howard (Sanofi). Medical writing assistance and editorial support, under the direction of the authors, were provided by Rachel Dunn, PhD, of Prime (Knutsford, UK), and funded by both Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. These data were presented at the Population Approach Group Europe Congress in Lisbon, Portugal, 2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors were involved in the study design and analysis, and interpretation of the data. All authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved it for submission. The authors take full responsibility for the content of this article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was funded by both Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Open Access publication of this article was sponsored by both Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Conflict of interest

Jean-Marie Martinez, Aurélie Brunet, Fabrice Hurbin, Clémence Rauch, and David Fabre are employees of and stockholders in Sanofi. A. Thomas DiCioccio is an employee of and stockholder in Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the studies. No identifying information for individual patients is included in this article.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Martinez, JM., Brunet, A., Hurbin, F. et al. Population Pharmacokinetic Analysis of Alirocumab in Healthy Volunteers or Hypercholesterolemic Subjects Using a Michaelis–Menten Approximation of a Target-Mediated Drug Disposition Model—Support for a Biologics License Application Submission: Part I. Clin Pharmacokinet 58, 101–113 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-018-0669-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-018-0669-y