Abstract

Background and Objectives

Sepsis is characterised by an excessive release of inflammatory mediators substantially affecting body composition and physiology, which can be further affected by intensive care management. Consequently, drug pharmacokinetics can be substantially altered. This study aimed to extend a whole-body physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) model for healthy adults based on disease-related physiological changes of critically ill septic patients and to evaluate the accuracy of this PBPK model using vancomycin as a clinically relevant drug.

Methods

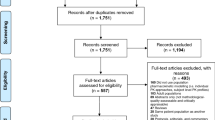

The literature was searched for relevant information on physiological changes in critically ill patients with sepsis, severe sepsis and septic shock. Consolidated information was incorporated into a validated PBPK vancomycin model for healthy adults. In addition, the model was further individualised based on patient data from a study including ten septic patients treated with intravenous vancomycin. Models were evaluated comparing predicted concentrations with observed patient concentration–time data.

Results

The literature-based PBPK model correctly predicted pharmacokinetic changes and observed plasma concentrations especially for the distribution phase as a result of a consideration of interstitial water accumulation. Incorporation of disease-related changes improved the model prediction from 55 to 88% within a threshold of 30% variability of predicted vs. observed concentrations. In particular, the consideration of individualised creatinine clearance data, which were highly variable in this patient population, had an influence on model performance.

Conclusion

PBPK modelling incorporating literature data and individual patient data is able to correctly predict vancomycin pharmacokinetics in septic patients. This study therefore provides essential key parameters for further development of PBPK models and dose optimisation strategies in critically ill patients with sepsis.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Daniels R. Surviving the first hours in sepsis: getting the basics right (an intensivist’s perspective). J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66 Suppl. 2:ii11–23. doi:10.1093/jac/dkq515.

Vincent JL, Sakr Y, Sprung CL, et al. Sepsis in European intensive care units: results of the SOAP study. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(2):344–53.

Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(16):1546–54. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa022139.

Dombrovskiy VY, Martin AA, Sunderram J, Paz HL. Rapid increase in hospitalization and mortality rates for severe sepsis in the United States: a trend analysis from 1993 to 2003. Crit Care Med. 2007;35(5):1244–50. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000261890.41311.E9.

Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis: the ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. Chest. 1992;101(6):1644–55.

Lee WL, Slutsky AS. Sepsis and endothelial permeability. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(7):689–91. doi:10.1056/NEJMcibr1007320.

Fishel RS, Are C, Barbul A. Vessel injury and capillary leak. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(8 Suppl.):S502–11. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000081431.50015.46.

Allen KS, Sawheny E, Kinasewitz GT. Anticoagulant modulation of inflammation in severe sepsis. World J Crit Care Med. 2015;4(2):105–15. doi:10.5492/wjccm.v4.i2.105.

Abdel-Razzak Z, Loyer P, Fautrel A, et al. Cytokines down-regulate expression of major cytochrome P-450 enzymes in adult human hepatocytes in primary culture. Mol Pharmacol. 1993;44(4):707–15.

Nicholson JP, Wolmarans MR, Park GR. The role of albumin in critical illness. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85(4):599–610.

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(2):165–228. doi:10.1007/s00134-012-2769-8.

De Paepe P, Belpaire FM, Buylaert WA. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations when treating patients with sepsis and septic shock. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41(14):1135–51. doi:10.2165/00003088-200241140-00002.

Gonzalez D, Conrado DJ, Theuretzbacher U, Derendorf H. The effect of critical illness on drug distribution. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011;12(12):2030–6.

Hosein S, Udy AA, Lipman J. Physiological changes in the critically ill patient with sepsis. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011;12(12):1991–5.

Edginton AN, Theil FP, Schmitt W, Willmann S. Whole body physiologically-based pharmacokinetic models: their use in clinical drug development. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2008;4(9):1143–52. doi:10.1517/17425255.4.9.1143.

Valentin J. Basic anatomical and physiological data for use in radiological protection: reference values. Ann ICRP. 2002;32(3–4):1–277.

Edginton AN, Willmann S. Physiology-based simulations of a pathological condition: prediction of pharmacokinetics in patients with liver cirrhosis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47(11):743–52. doi:10.2165/00003088-200847110-00005.

Bjorkman S, Wada DR, Berling BM, Benoni G. Prediction of the disposition of midazolam in surgical patients by a physiologically based pharmacokinetic model. J Pharm Sci. 2001;90(9):1226–41.

Xia B, Heimbach T, Gollen R, et al. A simplified PBPK modeling approach for prediction of pharmacokinetics of four primarily renally excreted and CYP3A metabolized compounds during pregnancy. AAPS J. 2013;15(4):1012–24. doi:10.1208/s12248-013-9505-3.

Edginton AN, Schmitt W, Willmann S. Development and evaluation of a generic physiologically based pharmacokinetic model for children. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2006;45(10):1013–34. doi:10.2165/00003088-200645100-00005.

Willmann S, Hohn K, Edginton A, et al. Development of a physiology-based whole-body population model for assessing the influence of individual variability on the pharmacokinetics of drugs. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2007;34(3):401–31. doi:10.1007/s10928-007-9053-5.

Willmann S, Lippert J, Sevestre M, et al. PK-Sim®: a physiologically based pharmacokinetic ‘whole-body’ model. Biosilico. 2003;1(4):121–4. doi:10.1016/S1478-5382(03)02342-4.

PK-Sim® software manual. http://www.pk-sim.com. Accessed 22 Aug 2016.

Cutler NR, Narang PK, Lesko LJ, et al. Vancomycin disposition: the importance of age. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1984;36(6):803–10.

Blouin RA, Bauer LA, Miller DD, et al. Vancomycin pharmacokinetics in normal and morbidly obese subjects. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1982;21(4):575–80.

Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16(1):31–41.

Usman M, Hempel G. Development and validation of an HPLC method for the determination of vancomycin in human plasma and its comparison with an immunoassay (PETINIA). SpringerPlus. 2016;5:124. doi:10.1186/s40064-016-1778-4.

Beckmann J, Kees F, Schaumburger J, et al. Tissue concentrations of vancomycin and Moxifloxacin in periprosthetic infection in rats. Acta Orthop. 2007;78(6):766–73. doi:10.1080/17453670710014536.

Kees MG, Wicha SG, Seefeld A, et al. Unbound fraction of vancomycin in intensive care unit patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;54(3):318–23. doi:10.1002/jcph.175.

Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-5-13.

Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:135. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-14-135.

Pea F, Furlanut M, Negri C, et al. Prospectively validated dosing nomograms for maximizing the pharmacodynamics of vancomycin administered by continuous infusion in critically ill patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53(5):1863–7. doi:10.1128/AAC.01149-08.

McNamara PJ, Alcorn J. Protein binding predictions in infants. AAPS PharmSci 4. 2002;1:E4. doi:10.1208/ps040104.

Sun H, Maderazo EG, Krusell AR. Serum protein-binding characteristics of vancomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37(5):1132–6.

Haussinger D, Roth E, Lang F, Gerok W. Cellular hydration state: an important determinant of protein catabolism in health and disease. Lancet. 1993;341(8856):1330–2.

Margarson MP, Soni NC. Effects of albumin supplementation on microvascular permeability in septic patients. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2002;92(5):2139–45. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00201.2001.

Margarson MP, Soni NC. Changes in serum albumin concentration and volume expanding effects following a bolus of albumin 20% in septic patients. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92(6):821–6. doi:10.1093/bja/aeh111.

Fleck A, Raines G, Hawker F, et al. Increased vascular permeability: a major cause of hypoalbuminaemia in disease and injury. Lancet. 1985;1(8432):781–4.

Fournier T, Medjoubi NN, Porquet D. Alpha-1-acid glycoprotein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1482(1–2):157–71.

Shedlofsky SI, Israel BC, McClain CJ, et al. Endotoxin administration to humans inhibits hepatic cytochrome P450-mediated drug metabolism. J Clin Invest. 1994;94(6):2209–14. doi:10.1172/JCI117582.

Shedlofsky SI, Israel BC, Tosheva R, Blouin RA. Endotoxin depresses hepatic cytochrome P450-mediated drug metabolism in women. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;43(6):627–32.

Carcillo JA, Doughty L, Kofos D, et al. Cytochrome P450 mediated-drug metabolism is reduced in children with sepsis-induced multiple organ failure. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(6):980–4. doi:10.1007/s00134-003-1758-3.

Novotny AR, Emmanuel K, Maier S, et al. Cytochrome P450 activity mirrors nitric oxide levels in postoperative sepsis: predictive indicators of lethal outcome. Surgery. 2007;141(3):376–84. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2006.08.011.

Kruger PS, Freir NM, Venkatesh B, et al. A preliminary study of atorvastatin plasma concentrations in critically ill patients with sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(4):717–21. doi:10.1007/s00134-008-1358-3.

Aitken AE, Morgan ET. Gene-specific effects of inflammatory cytokines on cytochrome P450 2C, 2B6 and 3A4 mRNA levels in human hepatocytes. Drug Metab Dispos. 2007;35(9):1687–93. doi:10.1124/dmd.107.015511.

Finn PJ, Plank LD, Clark MA, et al. Progressive cellular dehydration and proteolysis in critically ill patients. Lancet. 1996;347(9002):654–6.

Plank LD, Connolly AB, Hill GL. Sequential changes in the metabolic response in severely septic patients during the first 23 days after the onset of peritonitis. Ann Surg. 1998;228(2):146–58.

Cheng AT, Plank LD, Hill GL. Prolonged overexpansion of extracellular water in elderly patients with sepsis. Arch Surg. 1998;133(7):745–51.

Uehara M, Plank LD, Hill GL. Components of energy expenditure in patients with severe sepsis and major trauma: a basis for clinical care. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(7):1295–302.

Clark MA, Plank LD, Connolly AB, et al. Effect of a chimeric antibody to tumor necrosis factor-alpha on cytokine and physiologic responses in patients with severe sepsis: a randomized, clinical trial. Crit Care Med. 1998;26(10):1650–9.

Ritz P, Vol S, Berrut G, et al. Influence of gender and body composition on hydration and body water spaces. Clin Nutr. 2008;27(5):740–6. doi:10.1016/j.clnu.2008.07.010.

Marx G. Fluid therapy in sepsis with capillary leakage. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2003;20(6):429–42.

Clark MA, Hentzen BT, Plank LD, Hill GI. Sequential changes in insulin-like growth factor 1, plasma proteins, and total body protein in severe sepsis and multiple injury. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1996;20(5):363–70.

Abu-Zidan FM, Plank LD, Windsor JA. Proteolysis in severe sepsis is related to oxidation of plasma protein. Eur J Surg. 2002;168(2):119–23. doi:10.1080/11024150252884359.

Cohn SH, Vartsky D, Yasumura S, et al. Compartmental body composition based on total-body nitrogen, potassium, and calcium. Am J Physiol. 1980;239(6):E524–30.

Cohn SH, Vartsky D, Yasumura S, et al. Indexes of body cell mass: nitrogen versus potassium. Am J Physiol. 1983;244(3):E305–10.

Wang Z, Shen W, Kotler DP, et al. Total body protein: a new cellular level mass and distribution prediction model. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(5):979–84.

Vartsky D, Ellis KJ, Cohn SH. In vivo measurement of body nitrogen by analysis of prompt gammas from neutron capture. J Nucl Med. 1979;20(11):1158–65.

Burkinshaw L, Morgan DB, Silverton NP, Thomas RD. Total body nitrogen and its relation to body potassium and fat-free mass in healthy subjects. Clin Sci (Lond). 1981;61(4):457–62.

Lukaski HC, Mendez J, Buskirk ER, Cohn SH. A comparison of methods of assessment of body composition including neutron activation analysis of total body nitrogen. Metabolism. 1981;30(8):777–82.

Young JD. The heart and circulation in severe sepsis. Br J Anaesth. 2004;93(1):114–20. doi:10.1093/bja/aeh171.

Hunter JD, Doddi M. Sepsis and the heart. Br J Anaesth. 2010;104(1):3–11. doi:10.1093/bja/aep339.

Carlsson M, Andersson R, Bloch KM, et al. Cardiac output and cardiac index measured with cardiovascular magnetic resonance in healthy subjects, elite athletes and patients with congestive heart failure. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2012;14:51. doi:10.1186/1532-429X-14-51.

Tristani FE, Cohn JN. Studies in clinical shock and hypotension. VII. Renal hemodynamics before and during treatment. Circulation. 1970;42(5):839–51.

Brenner M, Schaer GL, Mallory DL, et al. Detection of renal blood flow abnormalities in septic and critically ill patients using a newly designed indwelling thermodilution renal vein catheter. Chest. 1990;98(1):170–9.

Prowle JR, Molan MP, Hornsey E, Bellomo R. Measurement of renal blood flow by phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging during septic acute kidney injury: a pilot investigation. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(6):1768–76. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318246bd85.

Lucas CE, Rector FE, Werner M, Rosenberg IK. Altered renal homeostasis with acute sepsis: clinical significance. Arch Surg. 1973;106(4):444–9.

Rector F, Goyal SC, Rosenberg IK, Lucas CE. Renal hyperemia in association with clinical sepsis. Surg Forum. 1972;23:51–3.

Zacho HD, Henriksen JH, Abrahamsen J. Chronic intestinal ischemia and splanchnic blood-flow: reference values and correlation with body-composition. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19(6):882–8. doi:10.3748/wjg.v19.i6.882.

Madsen JL, Sondergaard SB, Moller S. Meal-induced changes in splanchnic blood flow and oxygen uptake in middle-aged healthy humans. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2006;41(1):87–92. doi:10.1080/00365520510023882.

Takala J. Determinants of splanchnic blood flow. Br J Anaesth. 1996;77(1):50–8.

Sime FB, Udy AA, Roberts JA. Augmented renal clearance in critically ill patients: etiology, definition and implications for beta-lactam dose optimization. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2015;24:1–6. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2015.06.002.

Zarbock A, Gomez H, Kellum JA. Sepsis-induced acute kidney injury revisited: pathophysiology, prevention and future therapies. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2014;20(6):588–95. doi:10.1097/MCC.0000000000000153.

Abduljalil K, Furness P, Johnson TN, et al. Anatomical, physiological and metabolic changes with gestational age during normal pregnancy: a database for parameters required in physiologically based pharmacokinetic modelling. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2012;51(6):365–96. doi:10.2165/11597440-000000000-00000.

Rittirsch D, Hoesel LM, Ward PA. The disconnect between animal models of sepsis and human sepsis. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;81(1):137–43. doi:10.1189/jlb.0806542.

Michie HR. The value of animal models in the development of new drugs for the treatment of the sepsis syndrome. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1998;41 Suppl. A:47–9.

Poli-de-Figueiredo LF, Garrido AG, Nakagawa N, Sannomiya P. Experimental models of sepsis and their clinical relevance. Shock. 2008;30(Suppl. 1):53–9. doi:10.1097/SHK.0b013e318181a343.

The DrugBank database. http://www.drugbank.ca/drugs/DB00512. Accessed 31 Jul 2015.

Jia Z, O’Mara ML, Zuegg J, et al. Vancomycin: ligand recognition, dimerization and super-complex formation. FEBS J. 2013;280(5):1294–307. doi:10.1111/febs.12121.

Rybak M, Lomaestro B, Rotschafer JC, et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin in adult patients: a consensus review of the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66(1):82–98. doi:10.2146/ajhp080434.

Udy AA, Putt MT, Boots RJ, Lipman J. ARC: augmented renal clearance. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011;12(12):2020–9.

Lopes JA, Jorge S, Resina C, et al. Acute kidney injury in patients with sepsis: a contemporary analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;3(2):176–81. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2008.05.1231.

Oppert M, Engel C, Brunkhorst FM, German Competence Network S, et al. Acute renal failure in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: a significant independent risk factor for mortality: results from the German Prevalence Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(3):904–9. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfm610.

Dolton M, Xu H, Cheong E, et al. Vancomycin pharmacokinetics in patients with severe burn injuries. Burns. 2010;36(4):469–76. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2009.08.010.

Medellin-Garibay SE, Ortiz-Martin B, Rueda-Naharro A, et al. Pharmacokinetics of vancomycin and dosing recommendations for trauma patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(2):471–9. doi:10.1093/jac/dkv372.

Launay-Vacher V, Izzedine H, Mercadal L, Deray G. Clinical review: use of vancomycin in haemodialysis patients. Crit Care. 2002;6(4):313–6.

Dykhuizen RS, Harvey G, Stephenson N, et al. Protein binding and serum bactericidal activities of vancomycin and teicoplanin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39(8):1842–7.

Wittendorf RW, Swagzdis JE, Gifford R, Mico BA. Protein binding of glycopeptide antibiotics with diverse physical-chemical properties in mouse, rat, and human serum. J Pharmacokinet Biopharm. 1987;15(1):5–13.

Chen Y, Norris RL, Schneider JJ, Ravenscroft PJ. The influence of vancomycin concentration and the pH of plasma on vancomycin protein binding. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 1992;28(1):57–60.

Takács-Novák K, Noszál B. Acid-base properties and proton-speciation of vancomycin. Int J Pharm. 1993;89(3):261–3.

Magid E, Guldager H, Hesse D, Christiansen MS. Monitoring urinary orosomucoid in acute inflammation: observations on urinary excretion of orosomucoid, albumin, alpha1-microglobulin, and IgG. Clin Chem. 2005;51(11):2052–8. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2005.055442.

Ho JT, Al-Musalhi H, Chapman MJ, et al. Septic shock and sepsis: a comparison of total and free plasma cortisol levels. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(1):105–14. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0265.

Zeitlinger MA, Dehghanyar P, Mayer BX, et al. Relevance of soft-tissue penetration by levofloxacin for target site bacterial killing in patients with sepsis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(11):3548–53.

Sauermann R, Delle-Karth G, Marsik C, et al. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of cefpirome in subcutaneous adipose tissue of septic patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(2):650–5. doi:10.1128/AAC.49.2.650-655.2005.

Martin CP, Talbert RL, Burgess DS, Peters JI. Effectiveness of statins in reducing the rate of severe sepsis: a retrospective evaluation. Pharmacotherapy. 2007;27(1):20–6. doi:10.1592/phco.27.1.20.

Dahn MS, Mitchell RA, Lange MP, et al. Hepatic metabolic response to injury and sepsis. Surgery. 1995;117(5):520–30.

Doise JM, Aho LS, Quenot JP, et al. Plasma antioxidant status in septic critically ill patients: a decrease over time. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2008;22(2):203–9. doi:10.1111/j.1472-8206.2008.00573.x.

van der Flier M, van Leeuwen HJ, van Kessel KP, et al. Plasma vascular endothelial growth factor in severe sepsis. Shock. 2005;23(1):35–8.

Joynt GM, Lipman J, Gomersall CD, et al. The pharmacokinetics of once-daily dosing of ceftriaxone in critically ill patients. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2001;47(4):421–9.

Brink AJ, Richards GA, Schillack V, et al. Pharmacokinetics of once-daily dosing of ertapenem in critically ill patients with severe sepsis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2009;33(5):432–6. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.10.005.

Dolecek M, Svoboda P, Kantorova I, et al. Therapeutic influence of 20% albumin versus 6% hydroxyethylstarch on extravascular lung water in septic patients: a randomized controlled trial. Hepatogastroenterology. 2009;56(96):1622–8.

Memis D, Gursoy O, Tasdogan M, et al. High C-reactive protein and low cholesterol levels are prognostic markers of survival in severe sepsis. J Clin Anesth. 2007;19(3):186–91. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2006.10.008.

Joukhadar C, Klein N, Mayer BX, et al. Plasma and tissue pharmacokinetics of cefpirome in patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(7):1478–82.

Molnar Z, Mikor A, Leiner T, Szakmany T. Fluid resuscitation with colloids of different molecular weight in septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(7):1356–60. doi:10.1007/s00134-004-2278-5.

Joukhadar C, Frossard M, Mayer BX, et al. Impaired target site penetration of beta-lactams may account for therapeutic failure in patients with septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(2):385–91.

Crenn P, Neveux N, Chevret S, et al. Plasma L-citrulline concentrations and its relationship with inflammation at the onset of septic shock: a pilot study. J Crit Care. 2014;29(2):315 e311–6. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.11.015.

Bilgrami I, Roberts JA, Wallis SC, et al. Meropenem dosing in critically ill patients with sepsis receiving high-volume continuous venovenous hemofiltration. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(7):2974–8. doi:10.1128/AAC.01582-09.

Sallisalmi M, Tenhunen J, Kultti A, et al. Plasma hyaluronan and hemorheology in patients with septic shock: a clinical and experimental study. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2014;56(2):133–44. doi:10.3233/CH-131677.

Marx G, Vangerow B, Burczyk C, et al. Evaluation of noninvasive determinants for capillary leakage syndrome in septic shock patients. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(9):1252–8.

Iglesias J, Marik PE, Levine JS, Norasept II. Study Investigators. Elevated serum levels of the type I and type II receptors for tumor necrosis factor-alpha as predictive factors for ARF in patients with septic shock. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;41(1):62–75. doi:10.1053/ajkd.2003.50024.

Memis D, Kargi M, Sut N. Effects of propofol and dexmedetomidine on indocyanine green elimination assessed with LIMON to patients with early septic shock: a pilot study. J Crit Care. 2009;24(4):603–8. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.10.005.

Charpentier J, Mira J-P. Efficacy and tolerance of hyperoncotic albumin administration in septic shock patients: the EARSS study. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(Suppl. 1):S115.

Xiao K, Su L, Yan P, et al. alpha-1-Acid glycoprotein as a biomarker for the early diagnosis and monitoring the prognosis of sepsis. J Crit Care. 2015;30(4):744–51. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2015.04.007.

Barroso-Sousa R, Lobo RR, Mendonca PR, et al. Decreased levels of alpha-1-acid glycoprotein are related to the mortality of septic patients in the emergency department. Clinics. 2013;68(8):1134–9. doi:10.6061/clinics/2013(08)12.

Brinkman-van der Linden EC, van Ommen EC, van Dijk W. Glycosylation of alpha 1-acid glycoprotein in septic shock: changes in degree of branching and in expression of sialyl Lewis(x) groups. Glycoconj J. 1996;13(1):27–31.

Juncal VR, Britto Neto LA, Camelier AA, et al. Clinical impact of sepsis at admission to the ICU of a private hospital in Salvador. Brazil. J Bras Pneumol. 2011;37(1):85–92.

Reggiori G, Occhipinti G, De Gasperi A, et al. Early alterations of red blood cell rheology in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(12):3041–6. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181b02b3f.

Piagnerelli M, Boudjeltia KZ, Brohee D, et al. Modifications of red blood cell shape and glycoproteins membrane content in septic patients. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;510:109–14.

Davies GR, Mills GM, Lawrence M, et al. The role of whole blood impedance aggregometry and its utilisation in the diagnosis and prognosis of patients with systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis in acute critical illness. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e108589. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0108589.

Alt E, Amann-Vesti BR, Madl C, et al. Platelet aggregation and blood rheology in severe sepsis/septic shock: relation to the Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2004;30(2):107–15.

Kirschenbaum LA, Aziz M, Astiz ME, et al. Influence of rheologic changes and platelet-neutrophil interactions on cell filtration in sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(5):1602–7. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9902105.

Sanchez M, Jimenez-Lendinez M, Cidoncha M, et al. Comparison of fluid compartments and fluid responsiveness in septic and non-septic patients. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2011;39(6):1022–9.

Plataki M, Kashani K, Cabello-Garza J, et al. Predictors of acute kidney injury in septic shock patients: an observational cohort study. Clin J Am Soc Neprhol. 2011;6(7):1744–51. doi:10.2215/CJN.05480610.

Reinelt H, Radermacher P, Fischer G, et al. Effects of a dobutamine-induced increase in splanchnic blood flow on hepatic metabolic activity in patients with septic shock. Anesthesiology. 1997;86(4):818–24.

Udy AA, Roberts JA, Shorr AF, et al. Augmented renal clearance in septic and traumatized patients with normal plasma creatinine concentrations: identifying at-risk patients. Crit Care. 2013;17(1):R35. doi:10.1186/cc12544.

Wilhelm J, Hettwer S, Schuermann M, et al. Severity of cardiac impairment in the early stage of community-acquired sepsis determines worse prognosis. Clin Res Cardiol. 2013;102(10):735–44. doi:10.1007/s00392-013-0584-z.

Spanos A, Jhanji S, Vivian-Smith A, et al. Early microvascular changes in sepsis and severe sepsis. Shock. 2010;33(4):387–91. doi:10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181c6be04.

Guarracino F, Ferro B, Forfori F, et al. Jugular vein distensibility predicts fluid responsiveness in septic patients. Crit Care. 2014;18(6):647. doi:10.1186/s13054-014-0647-1.

Jakob SM, Ruokonen E, Takala J. Effects of dopamine on systemic and regional blood flow and metabolism in septic and cardiac surgery patients. Shock. 2002;18(1):8–13.

Michalopoulos A, Stavridis G, Geroulanos S. Severe sepsis in cardiac surgical patients. Eur J Surg. 1998;164(3):217–22. doi:10.1080/110241598750004670.

Klinzing S, Simon M, Reinhart K, et al. Moderate-dose vasopressin therapy may impair gastric mucosal perfusion in severe sepsis: a pilot study. Anesthesiology. 2011;114(6):1396–402. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e318219d74f.

Edul VS, Ince C, Navarro N, et al. Dissociation between sublingual and gut microcirculation in the response to a fluid challenge in postoperative patients with abdominal sepsis. Ann Intensive Care. 2014;4:39. doi:10.1186/s13613-014-0039-3.

Lorente JA, Landin L, De Pablo R, et al. Effects of blood transfusion on oxygen transport variables in severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 1993;21(9):1312–8.

Sair M, Etherington PJ, Peter Winlove C, Evans TW. Tissue oxygenation and perfusion in patients with systemic sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1343–9.

Wilkman E, Kaukonen KM, Pettila V, et al. Association between inotrope treatment and 90-day mortality in patients with septic shock. Acta Anaesth Scand. 2013;57(4):431–42. doi:10.1111/aas.12056.

Slagt C, de Leeuw MA, Beute J, et al. Cardiac output measured by uncalibrated arterial pressure waveform analysis by recently released software version 3.02 versus thermodilution in septic shock. J Clin Monit Comput. 2013;27(2):171–7. doi:10.1007/s10877-012-9410-9.

Hernandez G, Bruhn A, Luengo C, et al. Effects of dobutamine on systemic, regional and microcirculatory perfusion parameters in septic shock: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, crossover study. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(8):1435–43. doi:10.1007/s00134-013-2982-0.

Enrico C, Kanoore Edul VS, Vazquez AR, et al. Systemic and microcirculatory effects of dobutamine in patients with septic shock. J Crit Care. 2012;27(6):630–8. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2012.08.002.

Joly LM, Monchi M, Cariou A, et al. Effects of dobutamine on gastric mucosal perfusion and hepatic metabolism in patients with septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160(6):1983–6. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.160.6.9708113.

Gordon AC, Wang N, Walley KR, et al. The cardiopulmonary effects of vasopressin compared with norepinephrine in septic shock. Chest. 2012;142(3):593–605. doi:10.1378/chest.11-2604.

De Backer D, Creteur J, Dubois MJ, et al. The effects of dobutamine on microcirculatory alterations in patients with septic shock are independent of its systemic effects. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(2):403–8.

Pathil A, Stremmel W, Schwenger V, Eisenbach C. The influence of haemodialysis on haemodynamic measurements using transpulmonary thermodilution in patients with septic shock: an observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2013;30(1):16–20. doi:10.1097/EJA.0b013e328358543a.

Rank N, Michel C, Haertel C, et al. N-acetylcysteine increases liver blood flow and improves liver function in septic shock patients: results of a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Crit Care Med. 2000;28(12):3799–807.

Ruiz C, Hernandez G, Godoy C, et al. Sublingual microcirculatory changes during high-volume hemofiltration in hyperdynamic septic shock patients. Crit Care. 2010;14(5):R170. doi:10.1186/cc9271.

Hamzaoui O, Georger JF, Monnet X, et al. Early administration of norepinephrine increases cardiac preload and cardiac output in septic patients with life-threatening hypotension. Crit Care. 2010;14(4):R142. doi:10.1186/cc9207.

Wiramus S, Textoris J, Bardin R, et al. Isoproterenol infusion and microcirculation in septic shock. Heart Lung Vessel. 2014;6(4):274–9.

Leone M, Boyadjiev I, Boulos E, et al. A reappraisal of isoproterenol in goal-directed therapy of septic shock. Shock. 2006;26(4):353–7. doi:10.1097/01.shk.0000226345.55657.66.

Perner A, Haase N, Wiis J, et al. Central venous oxygen saturation for the diagnosis of low cardiac output in septic shock patients. Acta Anaesth Scand. 2010;54(1):98–102. doi:10.1111/j.1399-6576.2009.02086.x.

Palizas F, Dubin A, Regueira T, et al. Gastric tonometry versus cardiac index as resuscitation goals in septic shock: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Crit Care. 2009;13(2):R44. doi:10.1186/cc7767.

Creteur J, De Backer D, Sakr Y, et al. Sublingual capnometry tracks microcirculatory changes in septic patients. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(4):516–23. doi:10.1007/s00134-006-0070-4.

Georger JF, Hamzaoui O, Chaari A, et al. Restoring arterial pressure with norepinephrine improves muscle tissue oxygenation assessed by near-infrared spectroscopy in severely hypotensive septic patients. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36(11):1882–9. doi:10.1007/s00134-010-2013-3.

Klinzing S, Simon M, Reinhart K, et al. High-dose vasopressin is not superior to norepinephrine in septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(11):2646–50. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000094260.05266.F4.

Lauzier F, Levy B, Lamarre P, Lesur O. Vasopressin or norepinephrine in early hyperdynamic septic shock: a randomized clinical trial. Intensive Care Med. 2006;32(11):1782–9. doi:10.1007/s00134-006-0378-0.

Monnet X, Jabot J, Maizel J, et al. Norepinephrine increases cardiac preload and reduces preload dependency assessed by passive leg raising in septic shock patients. Crit Care Med. 2011;39(4):689–94. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318206d2a3.

Sakka SG, Kozieras J, Thuemer O, van Hout N. Measurement of cardiac output: a comparison between transpulmonary thermodilution and uncalibrated pulse contour analysis. Br J Anaesth. 2007;99(3):337–42. doi:10.1093/bja/aem177.

Albanese J, Leone M, Garnier F, et al. Renal effects of norepinephrine in septic and nonseptic patients. Chest. 2004;126(2):534–9. doi:10.1378/chest.126.2.534.

Auxiliadora Martins M, Coletto FA, Campos AD, Basile-Filho A. Indirect calorimetry can be used to measure cardiac output in septic patients? Acta Cir Bras. 2008;23 Suppl. 1:118–25 (discussion 125).

Morelli A, Rocco M, Conti G, et al. Effects of terlipressin on systemic and regional haemodynamics in catecholamine-treated hyperkinetic septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(4):597–604. doi:10.1007/s00134-003-2094-3.

Pierrakos C, Velissaris D, Scolletta S, et al. Can changes in arterial pressure be used to detect changes in cardiac index during fluid challenge in patients with septic shock? Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(3):422–8. doi:10.1007/s00134-011-2457-0.

Meier-Hellmann A, Bredle DL, Specht M, et al. The effects of low-dose dopamine on splanchnic blood flow and oxygen uptake in patients with septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23(1):31–7.

Levy B, Nace L, Bollaert PE, et al. Comparison of systemic and regional effects of dobutamine and dopexamine in norepinephrine-treated septic shock. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25(9):942–8.

Redl-Wenzl EM, Armbruster C, Edelmann G, et al. The effects of norepinephrine on hemodynamics and renal function in severe septic shock states. Intensive Care Med. 1993;19(3):151–4.

Guerin JP, Levraut J, Samat-Long C, et al. Effects of dopamine and norepinephrine on systemic and hepatosplanchnic hemodynamics, oxygen exchange, and energy balance in vasoplegic septic patients. Shock. 2005;23(1):18–24.

Meier-Hellmann A, Specht M, Hannemann L, et al. Splanchnic blood flow is greater in septic shock treated with norepinephrine than in severe sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(12):1354–9.

Meier-Hellmann A, Bredle DL, Specht M, et al. Dopexamine increases splanchnic blood flow but decreases gastric mucosal pH in severe septic patients treated with dobutamine. Crit Care Med. 1999;27(10):2166–71.

Kiefer P, Tugtekin I, Wiedeck H, e tal. Effect of a dopexamine-induced increase in cardiac index on splanchnic hemodynamics in septic shock. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(3 Pt 1):775–9. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.161.3.9901113.

Sakka SG, Meier-Hellmann A. Reinhart K.) Do fluid administration and reduction in norepinephrine dose improve global and splanchnic haemodynamics? Br J Anaesth. 2000;84(6):758–62.

Kern H, Schroder T, Kaulfuss M, et al. Enoximone in contrast to dobutamine improves hepatosplanchnic function in fluid-optimized septic shock patients. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(8):1519–25.

Meier-Hellmann A, Reinhart K, Bredle DL, et al. Epinephrine impairs splanchnic perfusion in septic shock. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(3):399–404.

De Backer D, Creteur J, Silva E, Vincent JL. The hepatosplanchnic area is not a common source of lactate in patients with severe sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2001;29(2):256–61.

Sakka SG, Reinhart K, Meier-Hellmann A. Does the optimization of cardiac output by fluid loading increase splanchnic blood flow? Br J Anaesth. 2001;86(5):657–62.

Mazul-Sunko B, Zarkovic N, Vrkic N, Antoljak N, Bekavac Beslin M, Nikolic Heitzler V, Siranovic M, Krizmanic-Dekanic A, Klinger R. Proatrial natriuretic peptide (1-98), but not cystatin C, is predictive for occurrence of acute renal insufficiency in critically ill septic patients. Nephron Clin Pract. 2004;97(3):c103–7. doi:10.1159/000078638.

Novelli A, Adembri C, Livi P, et al. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of meropenem and imipenem in critically ill patients with sepsis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44(5):539–49.

Kitzes-Cohen R, Farin D, Piva G, De Myttenaere-Bursztein SA. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of meropenem in critically ill patients. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2002;19(2):105–10.

Lherm T, Troche G, Rossignol M, et al. Renal effects of low-dose dopamine in patients with sepsis syndrome or septic shock treated with catecholamines. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22(3):213–9.

Lipman J, Wallis SC, Rickard CM, Fraenkel D. Low cefpirome levels during twice daily dosing in critically ill septic patients: pharmacokinetic modelling calls for more frequent dosing. Intensive Care Med. 2001;27(2):363–70.

Kieft H, Hoepelman AI, Knupp CA, et al. Pharmacokinetics of cefepime in patients with the sepsis syndrome. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1993;32 Suppl. B:117–22.

Schmoelz M, Schelling G, Dunker M, Irlbeck M. Comparison of systemic and renal effects of dopexamine and dopamine in norepinephrine-treated septic shock. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anestha. 2006;20(2):173–8. doi:10.1053/j.jvca.2005.10.016.

Deruddre S, Cheisson G, Mazoit JX, et al. Renal arterial resistance in septic shock: effects of increasing mean arterial pressure with norepinephrine on the renal resistive index assessed with Doppler ultrasonography. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(9):1557–62. doi:10.1007/s00134-007-0665-4.

Buijk SE, Mouton JW, Gyssens IC, et al. Experience with a once-daily dosing program of aminoglycosides in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28(7):936–42. doi:10.1007/s00134-002-1313-7.

Voerman HJ, Stehouwer CD, van Kamp GJ, et al. Plasma endothelin levels are increased during septic shock. Crit Care Med. 1992;20(8):1097–101.

Patel BM, Chittock DR, Russell JA, Walley KR. Beneficial effects of short-term vasopressin infusion during severe septic shock. Anesthesiology. 2002;96(3):576–82.

Girbes AR, Patten MT, McCloskey BV, et al. The renal and neurohumoral effects of the addition of low-dose dopamine in septic critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2000;26(11):1685–9.

Morelli A, Lange M, Ertmer C, et al. Short-term effects of phenylephrine on systemic and regional hemodynamics in patients with septic shock: a crossover pilot study. Shock. 2008;29(4):446–51. doi:10.1097/shk.0b013e31815810ff.

Fukuoka T, Nishimura M, Imanaka H, et al. Effects of norepinephrine on renal function in septic patients with normal and elevated serum lactate levels. Crit Care Med. 1989;17(11):1104–7.

Udy AA, Lipman J, Jarrett P, et al. Are standard doses of piperacillin sufficient for critically ill patients with augmented creatinine clearance? Crit Care. 2015;19:28. doi:10.1186/s13054-015-0750-y.

Israili ZH, Dayton PG. Human alpha-1-glycoprotein and its interactions with drugs. Drug Metab Rev. 2001;33(2):161–235. doi:10.1081/DMR-100104402.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This work was financially supported by a research grant from Bayer Technology Services GmbH as part of a PhD thesis of Christian Radke. The research grant was received by Georg Hempel (between 2012 and 2015).

Conflict of interest

Michaela Meyer and Thomas Eissing were employed by Bayer Technology Services GmbH during the preparation of the manuscript and are potential stock holders of Bayer AG, the holding owning Bayer Technology Services GmbH. Dagmar Horn, Christian Lanckohr and Björn Ellger have no potential conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Radke, C., Horn, D., Lanckohr, C. et al. Development of a Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Modelling Approach to Predict the Pharmacokinetics of Vancomycin in Critically Ill Septic Patients. Clin Pharmacokinet 56, 759–779 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-016-0475-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-016-0475-3