Abstract

Background

Current guidelines recommend prophylaxis with granulocyte colony-stimulating factors (G-CSFs) for patients with cancer who are at greater risk of febrile neutropenia (FN) while receiving chemotherapy. G-CSF biosimilars are available and represent a savings opportunity; however, their uptake has thus far been low.

Objective

Our objective was to evaluate prescribing patterns for G-CSFs in the prevention of chemotherapy-related FN and to evaluate the impact of regional guidance on G-CSF prescription.

Methods

We conducted an observational drug-utilization study in the Lazio region of Italy using the Electronic Therapeutic Plan Registry, which collects information on G-CSF prescriptions reimbursed by the regional health service. This registry includes information on demographics, tumour, indication for G-CSF use and previous G-CSF exposure. All therapeutic plans (TPs) registered from 1 July 2015 to 30 June 2016 were selected. A pharmaceutical policy intervention was implemented in November 2015. We evaluated temporal trends regarding G-CSF substances and compared the frequency of TPs for each G-CSF substance during the pre- and post-intervention periods.

Results

A total of 7082 TPs were eligible for the analysis, corresponding to 6592 patients. The frequency of TPs prescribed after the intervention indicated a significant increase in the use of a filgrastim biosimilar (% difference: 14.4; p < 0.001) and significant decreases in the use of lenograstim (% difference: –6.0; p < 0.001) and pegfilgrastim (% difference: –7.8; p < 0.001). The temporal trends analysis showed an increase in TPs using a filgrastim biosimilar (from 34.4% in July 2015 to 49.8% in June 2016; p < 0.0001) and a decrease in TPs using lenograstim and pegfilgrastim.

Conclusions

This study shows it is possible to change attitudes towards the prescription of less expensive G-CSFs in the FN setting when the prescriber’s decision-making processes are supported by evidence that includes both regulatory and clinical information and the analysis of clinical practice data.

Similar content being viewed by others

This study investigated the prescribing patterns for granulocyte colony-stimulating factors (G-CSFs) in a large real-world population included in a registry that was set up for clinical research purposes and included information on the indication for use (prevention of chemotherapy-related febrile neutropenia [FN]) and the clinical settings (naïve and experienced). |

Temporal trends showed a significant increase in the use of filgrastim biosimilars over time, rising to 50% in June 2016. |

The economic impact of guidance is estimated to save €500,000 per year, corresponding to almost 5% of the total yearly expenditure on G-CSFs in the Lazio region of Italy. |

1 Introduction

In patients with cancer undergoing myelosuppressive chemotherapy, which impairs the production of neutrophil granulocytes, febrile neutropenia (FN) is a potentially life-threatening complication with an estimated incidence of 10–50% of treated patients [1, 2]. FN often requires hospitalization and may result in reductions in chemotherapy doses and delays in chemotherapy regimens or surgery. FN also impairs antineoplastic treatment outcomes and is associated with an increased risk of serious infections and increased morbidity, mortality, and healthcare costs [3–5]. The mortality risk associated with FN is estimated at 5% for solid cancers and 11% for haematological cancers [6].

Current national and international guidelines recommend the prophylactic administration of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factors (G-CSFs) in patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy who have a ≥20% risk of FN [2, 7–9]. Moreover, patients with cancer and additional risk factors such as comorbidities or advanced age are eligible for G-CSF prophylaxis even if their risk of FN is <20%.

G-CSFs are biological growth factors that promote the proliferation, differentiation and activation of neutrophils in the bone marrow and include filgrastim, lenograstim, pegfilgrastim and lipegfilgrastim, all indicated to reduce the duration of neutropenia and the incidence of FN in patients with non-myeloid malignancies receiving myelosuppressive chemotherapy [10].

Filgrastim biosimilars have been authorized in the EU since 2008 [10], and a specific approval pathway for biosimilars, including a comprehensive comparability exercise, ensures similarity to the originator is demonstrated in terms of quality characteristics, biological activity, safety and efficacy [11]. Biological medicines, with their higher costs, have become a major concern for national healthcare systems operating in limited resource environments [12]. Recent analysis found filgrastim biosimilars to be cost efficient compared with other G-CSF originators, yielding potential budget savings that may then be allocated to newer antineoplastic therapies and improving patient access to them [13].

The market availability of biosimilars increases competition within the whole drug class and thus drives down prices. Substantial savings can be obtained, even when uptake of biosimilars is low [14]. The introduction of filgrastim biosimilars resulted in price reductions of almost 30% for the G-CSF class in the EU, albeit the price reduction was smaller in Italy.

Utilization data for Italy showed that, in 2015, filgrastim biosimilars represented 30.2% of the consumption and 15.3% of the expenditure for the entire G-CSF therapeutic class [15]. A wide variation in biosimilar consumption across Italian regions has also been documented; the Lazio region had one of the lowest uptakes of biosimilars in Italy [16].

In November 2015, the Lazio region issued a specific guidance with the aim of improving the appropriate prescription of G-CSFs [17]. The guidance considered all G-CSFs (biosimilar or not) therapeutically equivalent for the prevention of chemotherapy-related FN. As part of this process, a specific programme was established to monitor the implementation of the guidance using an existing Electronic Therapeutic Plan Registry (ETPR; set up in July 2015).

To our knowledge, no studies have evaluated the ability of guidance to change prescribing attitudes in real-world practice.

The objectives of this population-based study were to evaluate prescribing patterns for the use of G-CSFs in the prevention of chemotherapy-related FN and to evaluate the impact of the regional guidance on G-CSF prescription. As such, we conducted both a pre-post comparison analysis and a trends evaluation analysis and also explored intra-regional variability in the use of G-CSFs among different prescribing centres in the pre-post guidance period.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Source

We conducted an observational drug-utilization study in Lazio, a large Italian region with a resident population of approximately 6 million.

The study cohort was enrolled using the ETPR, which collects information on G-CSF prescriptions reimbursed and dispensed by the regional health service. Current Italian guidance [9] requires specialists to provide information to this registry for each patient treated with a G-CSF.

The ETPR collects information on patients’ demographic characteristics (age, sex), clinical data (tumour type, indication for G-CSF), G-CSF information (drug tradename, number of dispensed packages), therapy regimen (date of activation and duration of therapeutic plan [TP], in months) and prescribing centres as well as whether it is the first G-CSF prescription for each patient. Patient-level data are anonymized and de-identified prior to being released to investigators for analysis. Drug dispensing is coded according to the anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification system.

2.2 Study Population

We selected from the ETPR all TPs registered from 1 July 2015 to 30 June 2016 with G-CSF prescriptions for the prevention of chemotherapy-related FN, and we excluded TPs that lacked information on previous G-CSF exposure. The resulting cohort comprised two subpopulations: (1) treatment-naïve patients (incident patients without previous exposure to G-CSFs) and (2) treatment-experienced patients (prevalent patients previously exposed to G-CSFs).

2.3 Study Drugs

The study included all G-CSFs available in the region during the study period, as identified through the ATC code L03AA. In particular, we considered the following substances: (1) filgrastim originator (ATC: L03AA02; Granulokine®, Neupogen®); (2) filgrastim biosimilar (ATC: L03AA02; Nivestim®, Tevagrastim®, Zarzio®); (3) pegfilgrastim (ATC: L03AA13; Neulasta®); (4) lenograstim (ATC: L03AA10; Granocyte®, Myelostim®); and (5) lipegfilgrastim (ATC: L03AA14; Lonquex®). All these medicines are approved for the reduction of the duration of neutropenia and the incidence of FN in patients treated with cytotoxic chemotherapy.

2.4 Pharmaceutical Policy Intervention

All Italian residents are covered by the Italian National Health Service, which provides comprehensive hospital and outpatient care. Regions are responsible for organizing the service at the local level, including the development and implementation of drug policies. In May 2015, the Lazio region set up an ad hoc scientific committee (the biosimilar working group) to promote the rational and appropriate use of biosimilars. This committee reviewed both scientific literature and regulatory documents comparing the efficacy and safety of different G-CSFs and concluded that all G-CSFs (biosimilar or not) can be considered therapeutically equivalent for the prevention of chemotherapy-related FN. They developed evidence-based guidance to improve the appropriate use of G-CSFs in the Lazio region, and recommended a cost-effective approach for the procurement and prescription of G-CSFs. Finally, specific monitoring of guidance implementation via the existing ETPR was planned. The guidance entered into force in November 2015 [17].

2.5 Data Analysis

The index date was defined as the date of the activation of the first TP for a G-CSF, which is equivalent to the prescription date.

Both naïve and experienced users were described on the basis of demographic factors (age, sex), catchment area (Rome or other regional territories), tumour type and stage, setting of use (primary/secondary prophylaxis) and TP duration.

The pre- and post-pharmaceutical policy intervention periods were defined as July 2015–October 2015 and December 2015–June 2016, respectively. TPs issued in November 2015 (i.e. the month of policy intervention) were excluded.

We compared the frequency of TPs for each G-CSF during the pre- and post-intervention periods using the χ2 test for categorical variables in the two subpopulations.

We also calculated the temporal trends for G-CSF TPs by month in each population for each drug during the overall timeframe of July 2015–June 2016 using the Cochran–Armitage Trend Test.

Intra-regional variability was also evaluated, describing pre- and post-intervention changes in terms of percentages of TPs for different G-CSFs, across prescribing centres. Only centres prescribing at least 40 TPs during the study period were included in this analysis.

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software (version 9.2; Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

3 Results

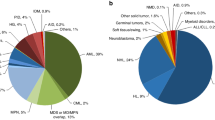

During the study period, we retrieved more than 8500 TPs for G-CSFs for chemotherapy-related FN (Fig. 1). After applying quality controls and the pre-defined inclusion criteria, 7082 TPs (83%) were eligible for analysis, corresponding to 6592 patients. This cohort comprised two subpopulations: TPs for treatment-naïve patients (n = 5261) and TPs for experienced patients (n = 1331). Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics, retrieved from the index TP, for the overall patient population by G-CSF. The majority of patients (42.2%) were receiving filgrastim biosimilars, followed by pegfilgrastim (26.4%) and lenograstim (17.0%). The mean age (60 years) was similar across the different G-CSFs. The prevalence of TPs was higher in women and in people from urban Rome. The most frequent tumour types at baseline were breast cancer (2001 of 6952), haematological malignancies (1387 of 6952) and lung cancers (933 of 6952).

There was substantial heterogeneity across different G-CSF TPs according to tumour type. The majority (66.9%) of patients presented with advanced-stage tumours, and the prevalence of TPs was similar across the substances except for filgrastim originator, which peaked at 85.5%. At least 60% of the patients received a G-CSF for the primary prophylaxis of FN, with a peak over 90% for pegfilgrastim and lipegfilgrastim; the prescription of a G-CSF to reduce the duration of FN was negligible (3.5%). The mean duration of TPs was similar across substances, ranging from 3.32 to 4.57 months. Descriptive analyses in the two subpopulations (naïve and experienced) found comparable results across the G-CSFs, except for lipegfilgrastim, where differences may be due to the very small patient population (Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] Tables 1 and 2).

Table 2 provides a comparison of the frequency of TPs prescribed before and after the policy intervention. The number of TPs using the filgrastim biosimilar increased significantly after the intervention (% difference: 14.4; p < 0.001), whereas TPs for lenograstim and pegfilgrastim significantly decreased (% difference: –6.0 and –7.8%, respectively; both p < 0.001). Similar results were obtained when the analyses were repeated in both subpopulations, although they appeared more sustained in the naïve setting (ESM Tables 3 and 4).

We investigated the temporal trends for TPs in the overall TP cohort over the study period according to G-CSF (Fig. 2). This analysis showed an increasing trend for TPs using the filgrastim biosimilar (from 34.4% in July 2015 to 49.8% in June 2016; p < 0.0001) compared with a decreasing trend for TPs using lenograstim (from 22.6% in July 2015 to 12.3% in June 2016; p < 0.0001) and pegfilgrastim (from 26.8% in July 2015 to 20.6% in June 2016; p < 0.0001). Similar trends were observed in the analyses of the two subpopulations (ESM, Figs. 1 and 2).

Temporal trends of the therapeutic plans prescribed to the overall patient population over the study period according to granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Cochran–Armitage Trend Test: filgrastim biosimilar p < 0.0001; filgrastim originator p = 0.0019; lenograstim p < 0.0001, lipegfilgrastim p < 0.0001; pegfilgrastim p < 0.0001

Figure 3 shows the intra-regional variability in TPs issued by centre pre- and post-intervention. In the overall TP cohort, 15 centres were responsible for more than 80% of the TPs using a G-CSF in the Lazio region; 13 of these were based in the Municipality of Rome. Both the overall and the subpopulation analyses found substantial heterogeneity in the prescription of G-CSFs across centres during both the pre- and the post-intervention periods. In the pre-intervention period, only two centres had at least 50% of TPs using the filgrastim biosimilar (Regina Elena—S. Gallicano Hospital, Rome, and SS Trinità Hospital, Sora), which increased to seven centres in the post-intervention period. After the intervention, four centres continued to have <30% of TPs using biosimilars (Campus biomedico, Rome; Sandro Pertini Hospital, Rome; S. Pietro Fatebenefratelli Hospital, Rome; IDI hospital, Rome); in addition, two of these centres (Sandro Pertini Hospital, Rome; S. Pietro Fatebenefratelli Hospital, Rome) had an increase of 55% in TPs using pegfilgrastim and one centre (IDI hospital, Rome) registered close to 30% of TPs using lipegfilgrastim. Repeating the analysis in the two subpopulations provided comparable results (ESM, Figs. 3 and 4).

4 Discussion

4.1 General Statement

This study investigated prescribing patterns for marketed G-CSFs in a large real-world population. Data were gathered from a registry established to collect information for clinical purposes on G-CSF use, such as indications for use (prevention of chemotherapy-related FN) and clinical settings (naïve and experienced). Specifically, a before–after analysis evaluating the impact of a policy intervention showed that the use of a filgrastim biosimilar increased after the intervention, whereas the use of lenograstim and pegfilgrastim decreased. Temporal trends also showed a significant increase in the use of filgrastim biosimilars over time, rising to 50% by June 2016. Intra-regional variability among prescribing centres was high both before and after the intervention, although we observed a growing number of centres with TPs prescribing at least 50% filgrastim biosimilars in the post-intervention period. The study findings were similar whether the analyses were conducted in naïve or experienced settings.

Our study confirmed that sharing evidence with prescribers and clinicians with the aim to deliver specific guidance on the appropriate use of drugs can induce significant changes in prescribing behaviours. Furthermore, we highlighted that regional guidance may reduce variability in prescribing patterns across centres, thus increasing appropriate drug use. We are also aware that reducing variability in prescribing patterns requires a longer follow-up to evaluate whether the effect of the guidance is stable over time and acknowledge that interventions aimed at changing prescribing behaviours to increase appropriate drug use must be sustained by further activities such as specific audit of less compliant centres.

4.2 Comparison with Other Studies

In the Lazio region in the pre-intervention period (July–October 2015), filgrastim biosimilars accounted for almost 33.8% of G-CSF use. This finding was in line with Italian utilization data for 2015, showing that filgrastim biosimilars represented almost 30% of G-CSF use. The intervention had a positive effect: the use of filgrastim biosimilars increased to almost 50% of G-CSFs.

Very few studies have evaluated prescribing patterns for G-CSF biosimilars. Two observational studies [18, 19] in clinical practice and involving almost 3000 patients investigated patterns for and outcomes of filgrastim biosimilars; their results were comparable with those historically reported for the originator drug. Neither study included a control group that received another G-CSF, as they were prospective surveillance studies for patients receiving filgrastim biosimilars.

A recent drug-utilization study [20] found that filgrastim biosimilar use reached >60% in 2014 but varied widely between five Italian regions in which different policies were implemented between 2009 and 2014. Moreover, the study highlighted a switch rate of >20% between different G-CSFs during the first year of treatment, mainly across G-CSF originators (involving the filgrastim originator, lenograstim and pegfilgrastim). However, this study relied solely on routinely collected prescription data. Our findings are in line with those of Marcianò et al. [20]: we observed an increased trend for filgrastim biosimilar use (almost 50% of G-CSF prescriptions) post-intervention. Furthermore, in our study, all relevant information was collected specifically for clinical purposes through the ETPR, including diagnosis, indication for use and previous G-CSF exposure.

Our study confirms that switching is feasible in the context of clinical practice within the Lazio region. It also suggests that switching patterns can be influenced or managed by specific guidance. In particular, guidance that included data demonstrating the therapeutic equivalency of G-CSFs increased confidence among prescribers about the interchangeability of G-CSFs.

4.3 Economic Impact

The results obtained in the post-intervention period could also be evaluated with regard to their economic impact on regional health service drug expenditure. In 2015, expenditure on G-CSFs in the Lazio region reached €9.9 million. We estimate the impact of the guidance over 1 year would increase biosimilar consumption by 20% and decrease that of lenograstim or pegfilgrastim by 10%. Barring any variations in the price per daily dose of G-CSFs, this would translate into an immediate savings of €500,000 in 2016, corresponding to almost 5% of the total yearly expenditure on G-CSFs in this region. Maintaining the effects of the guidance with further educational activities and audits of prescribers, especially of those who are less adherent to the guidance, may further increase such savings while ensuring the same level of care.

4.4 Potential Impact on Future Policies

The most recent guideline confirms the therapeutic equivalency of G-CSFs (including biosimilars) in the prevention of chemotherapy-related FN [7]. This guideline states that the choice of agent depends on convenience, cost and clinical situation and notes no new additional trial data are available to compare G-CSFs.

On the other hand, ‘position papers’ issued over recent years by learned societies and national agencies only focus on equivalence between biosimilars and originators [21–27] and appear to be controversial, reporting different provisions regarding interchangeability and substitution between originators and biosimilars.

No study has analysed the impact of a recommendation in terms of its ability to change real-world prescribing patterns. In this context, our study showed that a structured process that included a shared evidence review between policy makers and clinical practitioners, together with a programme to monitor prescriptions, might substantially affect physicians’ attitudes to choosing between G-CSFs (biosimilars or originators). Given the therapeutic equivalency of G-CSFs in terms of efficacy and safety, the prescription of a G-CSF may be more appropriately directed towards the less expensive drug.

By directly involving health operators in the definition of common and shared documents that highlight the lack of significant clinical data to support the use of a specific G-CSF over another in the FN setting, we were able to change prescribing patterns in the Lazio region to reach national standards. Thus, we have proved that variability among geographical areas may be modified throughout interventions associated with a continuous monitoring system.

4.5 Strengths and Limitations

This study has several strengths. The data source (ETPR) was set up specifically for clinical research purposes, ensuring minimal misclassification of diagnoses, accurate identification of naïve and experienced users and a selected cohort of patients for whom G-CSFs are deemed appropriate.

Furthermore, our population-based study was conducted region-wide in the second largest Italian region by resident population and included all patients treated with a G-CSF (biosimilar or originator). Moreover, no particular group of patients receiving G-CSFs was selected.

The main limitation of this study was the narrow timeframe available for the impact analysis of the guidance; the prescribing trends we observed should be confirmed over a longer follow-up period. In addition, given the descriptive nature of the study, no hypothesis was tested via a logistic regression model, and our study did not allow an assessment of prescribing pattern changes in terms of clinical outcomes.

5 Conclusion

This study investigated the prescribing patterns for marketed G-CSF substances in a large real-world population and showed a significant increase in the use of filgrastim biosimilars and less variability among prescribing centres post-intervention. Analyses in both naïve and experienced settings resulted in similar findings.

This study indicates that a decision process supported by evidence that includes both regulatory and clinical information, together with the analysis of clinical practice data, can alter attitudes regarding the use of G-CSFs; in particular, we were able to shift prescriptions towards less expensive drugs in the FN setting.

This analysis also shows that pharmaceutical policy decisions should be continuously monitored over time to evaluate their impact in clinical practice.

References

Lyman GH, Kuderer N, Greene J, Balducci L. The economics of febrile neutropenia: implications for the use of colony-stimulating factors. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1857–64.

Crawford J, Caserta C, Roila F, ESMO Guidelines Working Group. Hematopoietic growth factors: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the applications. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v248–51.

Caggiano V, Weiss RV, Rickert TS, Linde-Zwirble WT. Incidence, cost, and mortality of neutropenia hospitalization associated with chemotherapy. Cancer. 2005;109:1916–24.

Crawford J, Dale DC, Lyman GH. Chemotherapy-induced neutropenia: risks, consequences, and new directions for its management. Cancer. 2004;100:228–37.

Kuderer NM, Dale DC, Crawford J, Cosler LE, Lyman GH. Mortality, morbidity, and cost associated with febrile neutropenia in adult cancer patients. Cancer. 2006;106:2258–66.

de Naurois J, Novitzky-Basso I, Gill MJ, Marti FM, Cullen MH, Roila F, ESMO, Guidelines Working Group. Management of febrile neutropenia: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(Suppl 5):v252–6.

Smith TJ, Bohlke K, Lyman GH, et al. Recommendations for the use of WBC growth factors: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:3199–212.

National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical practice guidelines in oncology: myeloid growth factors. http://www.nccn.org. Accessed 16 Dec 2016.

Associazione Italiana di Oncologia Medica. Linee guida AIOM. Gestione della tossicità ematopoietica in oncologia. Milan: AIOM; 2016. http://www.aiom.it/professionisti/documenti-scientifici/linee-guida/1,413,1. Accessed 16 Dec 2016.

European Medicines Agency. http://www.ema.europa.eu/ema/index.jsp?curl=pages/medicines/landing/epar_search.jsp&mid=WC0b01ac058001d124. Accessed 16 Dec 2016.

European Medicines Agency. Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP). Guideline on similar biological medicinal products containing biotechnology-derived proteins as active substance: non-clinical and clinical issues (EMEA/CHMP/BMWP/42832/2005 Rev1). London: EMA; 2014, p. 13. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2015/01/WC500180219.pdf. Accessed 16 Dec 2016.

Blackstone EA, Fuhr JP. The economics of biosimilars. Am Health Drug Benef. 2013;6:469–78.

Sun D, Andayani TM, Altyar A, MacDonald K, Abraham I. Potential cost savings from chemotherapy-induced febrile neutropenia with biosimilar filgrastim and expanded access to targeted antineoplastic treatment across the European Union G5 countries: a simulation study. Clin Ther. 2015;37:842–57.

IMS Health Report. The impact of biosimilar competition on price, volume and market share—updated version 2016. June 2016. http://ec.europa.eu/growth/tools-databases/newsroom/cf/itemdetail.cfm?item_id=8854. Accessed 16 Dec 2016.

Italian Medicines Agency. The Medicines Utilisation Monitoring Centre (OsMed). National report on medicines use in Italy. Year 2015. Rome: OsMed; 2016, p. 566. http://www.agenziafarmaco.gov.it/it/content/rapporti-osmed-luso-dei-farmaci-italia. Accessed 16 Dec 2016.

Traversa G (oral presentation). Italian National Institute of Health. Seminar on biosimilars. June 2015. http://www.epicentro.iss.it/farmaci/pdf/biosimilari2015/Traversa.pdf. Accessed 16 Dec 2016.

Gruppo di lavoro regionale farmaci biosimilari. Linee di indirizzo per l’uso appropriato dei fattori di crescita leucocitaria (G-CSF) nel Lazio. 9 November 2015. http://www.deplazio.net/it/documenti-corefa/212-linee-di-indirizzo-per-luso-appropriato-dei-fattori-di-crescita-leucocitaria-g-csf. Accessed 16 Dec 2016.

Gascón P, Aapro M, Ludwig H, et al. Treatment patterns and outcomes in the prophylaxis of chemotherapy-induced (febrile) neutropenia with biosimilar filgrastim (the MONITOR-GCSF study). Support Care Cancer. 2016;24:911–25.

Tesch H, Ulshöfer T, Vehling-Kaiser U, Ottillinger B, Bulenda D, Turner M. Prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced neutropenia with the biosimilar filgrastim: a non-interventional observational study of clinical practice patterns. Oncol Res Treat. 2015;38:146–52.

Marcianò I, Ingrasciotta Y, Giorgianni F, et al. How did the introduction of biosimilar filgrastim influence the prescribing pattern of granulocyte colony-stimulating factors? Results from a multicentre, population-based study, from five Italian centres in the years 2009–2014. BioDrugs. 2016;30:295–306.

Barosi G, Bosi A, Abbracchio MP, et al. Key concepts and critical issues on epoetin and filgrastim biosimilars. A position paper from the Italian Society of Hematology, Italian Society of Experimental Hematology, and Italian Group for Bone Marrow Transplantation. Haematologica. 2011;96:937–42.

Schofield I. Boost for biosimilar switching as Finns add their backing. Scrip 2015, May 26. http://www.scripintelligence.com/policyregulation/Boost-for-biosimilar-switching-as-Finns-add-their-backing-358581. Accessed 16 Dec 2016.

Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GABI). Dutch medicines agency says biosimilars ‘have no relevant differences’ to originators. Mol: GABI; 2015. http://www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/General/Dutch-medicines-agency-says-biosimilars-have-no-relevant-differences-to-originators. Accessed 16 Dec 2016.

Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GABI). France to allow biosimilars substitution. Mol: GABI; 2014. http://gabionline.net/Policies-Legislation/France-to-allow-biosimilars-substitution. Accessed 16 Dec 2016.

European Biopharmaceutical Enterprises. French Biosimilar Law—No generics-style substitution policy. 2014. http://www.ebe-biopharma.eu/newsroom/download/54/document/ebe-bs-statement-final_24.01.2014.pdf. Accessed 16 Dec 2016.

Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GABI). Australia’s PBAC recommends substitution of biosimilars. Mol: GABI; 2015. http://www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/General/Australia-s-PBAC-recommends-substitution-of-biosimilars. Accessed 16 Dec 2016.

Generics and Biosimilars Initiative (GABI). Biosimilars policies in Italy. Mol: GABI; 2012. http://www.gabionline.net/Reports/Biosimilars-policies-in-Italy. Accessed 16 Dec 2016.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Francesco Trotta, Flavia Mayer, Alessandra Mecozzi, Laura Amato and Antonio Addis have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was based on routinely collected data that were retrospectively analysed; therefore, ethical approval was not required. Only anonymised data were used. Informed consent is not required for this type of study.

Funding

Only public employees of the regional health authorities were involved in conceiving, planning, and conducting the study; no additional funding was received.

Author Contributions

All authors made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work and/or to the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of the data. All authors were involved in developing and critically revising the content of the manuscript, and all provided final approval of the version submitted for publication. None of the results presented in the current manuscript have been published elsewhere.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Trotta, F., Mayer, F., Mecozzi, A. et al. Impact of Guidance on the Prescription Patterns of G-CSFs for the Prevention of Febrile Neutropenia Following Anticancer Chemotherapy: A Population-Based Utilization Study in the Lazio Region. BioDrugs 31, 117–124 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-017-0214-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40259-017-0214-9