Abstract

Low back pain is one of the most common causes for seeking medical treatment and it is estimated that one in two people will experience low back pain at some point during their lifetimes. Management of low back pain includes pharmacological and non-pharmacological approaches. Non-pharmaceutical treatments include interventions such as acupuncture, spinal manipulation, and psychotherapy. The latter is especially important as patients who suffer from low back pain often have impaired quality of life and also suffer from depression. Depressive symptoms can appear because back pain limits patients’ ability to work and engage in their usual social activities. The aim of this systematic review was to overview the behavioral approaches that can be used in the management of patients with low back pain. Approaches such as electromyography (EMG) biofeedback, cognitive behavioral therapy, and mindfulness-based stress reduction are discussed as non-pharmacological options in the management of low back pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is defined as pain and discomfort below the costal margin and above the inferior gluteal folds [1]. It is one of the most common causes for seeking medical treatment and it is estimated that 1 in 2 people will experience low back pain at some point during their lifetimes [1].

The temporal evolution of symptoms divides low back pain into acute (symptoms lasting < 4 weeks), sub-acute (symptoms lasting 4–12 weeks) or chronic (symptoms lasting at least 3 months). Chronic LBP will affect at least 10% of low back pain sufferers [2].

Further classification of LBP depends on whether it shows a specific correlation to an underlying pathology. Specific LBP correlates with a local infection, injury, trauma or structural deformity, whereas in non-specific LBP no causal pathology is found. In such cases, factors other than anatomic probably play an important role in generating pain. Such factors include muscle spasms and back strains [1].

Management of low back pain includes pharmacological [3] and non-pharmacological approaches. Non-pharmaceutical treatments include interventions such as acupuncture, spinal manipulation, and psychotherapy. The latter is especially important, as patients who suffer from low back pain often suffer from depression [4] and have impaired quality of life, as they are unable to work and engage in their usual social activities because of their disability.

The aim of this paper was to systematically review the evidence regarding the effectiveness of behavioral approaches in the management of patients with LBP.

Overview of Behavioral Therapy Approaches

Behavioral therapy is a broad term referring to clinical psychotherapy that uses techniques derived from behaviorism and is often used in conjunction with cognitive psychology. Over the years, behavioral therapy has evolved and currently three “waves” of behavioral therapy are recognized, the characteristics of which are summarized in Table 1.

First Wave

Classic behavioral therapy is considered as the “first wave” of behavioral therapy approaches. This kind of psychotherapy is based on behavioral learning in which the therapist assists the patient to overcome stressful situations by teaching relaxation skills. The therapy aims to reduce maladaptive behaviors and simultaneously encourage the patient to adopt new behaviors that facilitate their day-to-day lives by providing social and problem-solving skills training [5].

Second Wave

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), the most commonly used and studied type of psychotherapy, represents the second wave of behavioral approaches. CBT focuses on the development of individual strategies aiming to solve current problems and to change unhelpful patterns in cognitions (i.e., thoughts and beliefs), behaviors, and emotional regulation [6].

CBT can be delivered in different ways: as an individual face-to-face therapy, the success of which relies to a significant degree on the patient—therapist relationship; as a self-administered therapy, which can be done by using materials (i.e., reading books or using the Internet) teaching how to implement CBT without the guidance of a mental health professional [7]; or as a group treatment. The latter is notable, as it confronts social isolation, which is an important aspect in the case of chronic pain. It is well known that the interaction with other people is a powerful way of creating a shift out of pain pathways leading to decreased pain perception [8].

Third Wave

Third wave therapies prioritize the holistic promotion of health and well-being and are less focused on reducing psychological and emotional symptoms. These therapies abandon key assumptions associated with traditional cognitive therapy informed by emerging research in cognitive psychology and neuroscience. Concepts such as metacognition, acceptance, mindfulness, personal values, and spirituality are frequently incorporated into what might otherwise be considered traditional behavioral interventions [9].

Literature Search Strategy

Literature Search Strategy

A systematic computer-based literature search was conducted on February 19, 2018, on PubMed database. For the search we used two Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms in either title or abstract. Term A was “low back pain” and Term B was “behavioral therapy” or “behavioral therapy”. We also perused the reference lists of the papers in order to find papers not found through the search strategy.

Inclusion Criteria

To be included in the review, the articles had to meet the following criteria:

-

1.

to be original research (including trials, observational studies, and case series),

-

2.

to study human adult subjects,

-

3.

to be in english,

-

4.

to primarily focus on the effectiveness of behavioral therapy,

-

5.

to involve patients with low back pain.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

Search Results

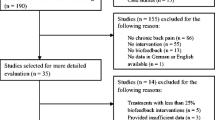

Our search strategy resulted in the identification of 132 articles. After eligibility assessment, 98 articles were excluded. Scanning the reference lists yielded eight more papers. In total, 42 papers met the inclusion criteria and were used for this review [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51]. The characteristics of these studies are summarized in Table 2. Figure 1 illustrates the study selection process.

Biofeedback

The predominant, purely behavioral, individual approach that has been studied in LBP is biofeedback. Biofeedback is a relaxation technique that focuses on educating patients to alter brain activity, blood pressure, heart rate, and other autonomic nervous system functions that normally are not controlled voluntarily [52, 53].

Electromyography (EMG) biofeedback has been successful in reducing standing levels of paraspinal muscle tension in patients with chronic low back pain [44]; however studies of EMG-biofeedback in LBP have not provided robust data supporting a direct analgesic effect [45].

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

CBT is the most common type of psychotherapy that has been applied in LBP, in adults of all age groups [36].

Four components summarize the theoretical background of CBT in the management of LBP: (1) the patient’s knowledge and understanding about pain and pain perception, (2) the use of active coping skills, (3) the maintenance of behavioral pain-coping strategies (such as activity pacing and pleasant activity scheduling), and (4) problem-solving methods that enable patients to analyze and develop plans for dealing with pain or other challenging situations [54].

Cognitive relearning aims to shift attention from incorrect and erratic thoughts and fears to adaptive thought patterns. In patients with LBP, activity pacing and graded exposure to situations that they have previously avoided may lead to increases in the levels of activity [55]. The main assumption is that patients’ thoughts and beliefs about their disease or symptoms will influence their feelings and physiological reactions and consequently their behaviors [56]. Congruently, a strong link between negative beliefs and increased pain perception has been shown in several studies of chronic LBP patients [57]. In addition, chronic LBP can lead to functional alterations in the circuitry underlying the cognitive control of pain [11]. The link between pain-related thought suppression and brain morphology may provide a new perspective on the understanding of the cognitive control of pain in chronic LBP, which may help improve the outcomes of cognitive behavioral therapy [11].

The Role of Patients’ Expectations

A psychological factor that is an important prognostic determinant in LBP is health locus of control [58, 59]. Health locus of control is defined as patients’ perception of who is responsible for their condition. There are three types of health locus of control: internal (patients believe that they are responsible for their own condition), external (patients believe that others are responsible for their condition), and chance (patients believe that their condition is determined by chance) [60]. People with LBP with higher levels of external locus of control have a poorer prognosis and have greater expectations from treatment. It has been shown that patients’ expectations [32, 34] and patients’ preferences for the type treatment [35] influence the outcome in patients with chronic LBP.

Patients with an external locus of control have difficulty coping with their symptoms [54]. CBT interventions have the scope to address a patient’s health locus of control perception and coping skills [55]. Adaptive coping, as a personality trait, is associated with better pain-related functioning [30], and CBT as part of rehabilitation can encourage such beneficial pain coping behavior by altering patients’ pain perception, thereby reducing the adverse effects of pain [20, 38]. Therefore, the modification of patients’ beliefs about the nature and treatment of their pain may be associated with improvements in patients’ perceptions of the level of their disability [38].

Graded Activity and Exposure

Graded activity and graded exposure incorporate behavioral and cognitive approaches to improve activity tolerance [61]. Such approaches have been tested in both individual [24, 31] and group [16] sessions.

Individual-graded activity sessions have shown similar effectiveness compared to physiotherapy [24] and motor control exercises [31] in patients with chronic nonspecific LBP. In an observational study of patients with chronic LBP, group sessions of graded activity showed significant improvement in pain intensity [16].

Besides the effect on pain intensity, behavioral-graded activity has also proven to be a successful method of restoring occupational function and facilitating return to work in patients with sub-acute LBP [41].

Individual CBT

In a randomized prospective study, Brox et al. compared focused CBT intervention for physical activation with spine fusion surgery for LBP. CBT had similar effects with fusion surgery, but at 12 months the CBT group showed less fear avoidance [47]. A longer-term follow-up confirmed these findings even at 4-years [62].

In the majority of the studies, CBT was implemented as part of an add-on multidisciplinary approach [13, 14, 18, 26,27,28,29, 37]. However, the effectiveness of a multidisciplinary approach incorporating CBT in reducing pain intensity compared to standard care remains controversial.

Some studies report significantly greater improvements in mean pain intensity when CBT was used [28, 29]; however in other studies, the multidisciplinary approach had no significant impact on pain management [10, 18, 26, 27, 37, 46]. Moreover, the multidisciplinary rehabilitation program including CBT has been found to be superior to the usual care practice alone. This superiority has been observed in aspects such as reducing disability and kinesiophobia, decatastrophizing [22, 28], and enhancing quality of life of LBP sufferers [22, 27, 37].

Possible explanations about the controversy in these findings include the heterogeneity of the studied populations, the differences between the multidisciplinary approaches and the CBT characteristics per se. It is of interest that there were less psychotherapy sessions (ranging from 3 to 8 sessions) in the studies showing no analgesic effect of CBT compared to those studies where CBT effectively reduced pain intensity (total number of sessions ranged from 10 to 36).

Group CBT

Group-based CBT has been used to address environmental, social, and emotional influences on pain experience, depression, and decreased activity from chronic LBP [43].

A group-based, multidisciplinary, cognitive behavioral rehabilitation program was found to be superior to traditional exercises in reducing pain and kinesiophobia, decatastrophizing, and enhancing quality of life of subjects with chronic LBP, with the effects lasting for at least 2 years after the end of the intervention [22]. However, small-group CBT showed similar effects with no significant differences either post-treatment or at 6-month follow-up, when compared to EMG biofeedback [40].

Outpatient group CBT, based on the negative reinforcement of pain behaviors, effectively reduced pain intensity for up to 12 months post treatment. When combined with aerobic exercise, pain intensity was shown to improve sooner [42].

CBT in Acute LNP

Catastrophic thinking and fear-avoidance beliefs can negatively influence severe acute pain following surgical operation, which can lead to delayed ambulation and discharge [21]. Preoperative CBT appears to facilitate mobility in the acute post-surgical phase; despite high levels of acute post-surgical pain reported by patients, there was a slightly lower intake of rescue painkillers in the CBT group. This evidence may suggest an overall improved ability to cope with pain post-surgically following pre-operative CBT intervention in patients with acute LBP [21].

In an interesting study comparing individual CBT and EMG biofeedback in patients with acute LBP, Hasenbring et al. showed that both techniques are effective; however CBT was superior to EMG biofeedback intervention in pain relief [39]. Overall, individually scheduled, risk factor-based CBT could be a beneficial treatment modality that can be offered, in addition to medical treatment, as it may be an effective way to prevent chronification in these patients [39].

Other Forms of CBT

Neither telephone-based CBT [12] nor the use of a cognitive behavioral videotape, as an adjunct to treatment, was found to be superior to standard care in the management of LBP [33].

Additional Effects of CBT in the Management of LBP

CBT can also target other symptoms in addition to pain in patients with LBP. For example, poor sleep quality is common in LBP patients; however, it is still debatable whether lack of sleep exacerbates pain or whether pain prevents sleep [63]. One study showed that poor sleep is a better predictor of disability than the actual severity of pain [64]. Insomnia-focused CBT is an example of a problem-focused therapy intended to improve the quality of sleep [65].

Similarly, depression and stress augment perception of pain [66, 67]. Targeting anxiety and depression can therefore indirectly decrease pain perception. Furthermore, working on pain de-catastrophizing through CBT sessions can help patients regain their functionality [68].

Third Wave Approaches

Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction

Mindfulness is a fundamental construct in the practice of Buddhist meditation but has also been described as a specific state of consciousness. This state is defined as a non- elaborative, non-judgmental, moment-to-moment awareness or an ability to trust one’s own experience [69].

Mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) is the most common mindfulness-based intervention. Methods of this practice include sitting and walking meditation, yoga, and body scan, a sustained mindfulness practice that promotes greater awareness of the body by sequential focus on different parts of the body [69].

LBP patients have shown promising results in mindfulness-based meditation programs [17, 48,49,50]. Supplementary therapy with MBSR rather than usual care alone can result in greater improvement in back pain and functional limitations [15, 23]. Mindfulness-based interventions are also feasible, acceptable, and safe in opioid-treated chronic LBP [19, 51]. Based on this evidence and the successful use of this type of intervention in older adults [49, 50], mindfulness-based interventions provide a valuable approach to pain management that is applicable to the whole spectrum of patients with LBP.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

The acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) targets ineffective pain control strategies and experiential avoidance [70]. Using ACT, patients learn how to accept unpleasant feelings, sensations, and thoughts. Although negative pain-associated thoughts are targeted, there is no effort to change their irrational content in this form of therapy [70]. Developing mindfulness is one of the fundamental strategies in ACT along with value clarification and developing the patients’ ability to commit to these values in their daily lives.

Pain reduction is not the target of acceptance-based therapies. Participants learn to let go of ineffective pain control strategies and work with the therapist on how to accept pain. Therefore, whether pain intensity is an appropriate outcome measure for acceptance-based interventions in chronic pain patients remains debatable. Upcoming research should not only rely on pain intensity as an outcome but also include other parameters such as interference of pain with daily life [71].

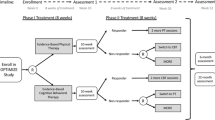

Studies of ACT in LBP are lacking. Currently, a randomized controlled trial of physiotherapy informed by acceptance and commitment therapy (PACT) versus usual physiotherapy for adults with chronic LBP is underway [72].

Contextual Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

Contextual cognitive behavioral therapy (CCBT) is a treatment approach that has also been tried in LBP, and combines CBT with ACT [25]. The content of each session in CCBT is not structured and the specific features of CCBT deemed appropriate for each patient are at the discretion of the therapist. For example, the first session is dedicated to building a good relationship with patients and determining the expectations about the content and the rationale of subsequent sessions. Subsequent sessions include a mixture of techniques based on enhancing acceptance through experiential, exposure-based and mindfulness-based methods using present moment focus and directed awareness [25].

Conclusions and Future Directions

This systematic review indicates the following key points:

-

1.

Behavioral therapy approaches are effective in patients with LBP particularly in altering pain perception and helping patients to regain their functionality.

-

2.

Treatment outcomes can be improved if the treatments are personalized to individual patients’ needs [73, 74].

-

3.

A multidisciplinary approach is the future. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation includes more than just physical treatment. A team approach accounting for several aspects within the bio-psychosocial model is more likely to help individuals with chronic LBP compared to standard care alone.

-

4.

CBT is the type of psychotherapy that has been most studied in patients with LBP. Although most of the other behavioral therapy interventions have been tried in randomized trials in other conditions, more trials of such approaches are needed in patients with LBP.

-

5.

Future research, however, must focus on the improvement of specific outcomes, using not only measures of pain intensity but also using measures of pain acceptance, reduction of medication used, disability, and quality of life to assess efficacy. Also, a comparison of the effectiveness of the different psychotherapy approaches on the different outcomes is important to tailor the therapeutic approach to a patient’s specific needs.

References

Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Thomas S. Diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. BMJ. 2006;332(7555):1430–4.

Meucci RD, Fassa AG, Faria NM. Prevalence of chronic low back pain: systematic review. Rev Saude Publ. 2015;49. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-8910.2015049005874.

Zis P, Bernali N, Argira E, Siafaka I, Vadalouka A. Effectiveness and impact of capsaicin 8% patch on quality of life in patients with lumbosacral pain: an open-label study. Pain Phys. 2016;19(7):E1049–53.

Zis P, Daskalaki A, Bountouni I, Sykioti P, Varrassi G, Paladini A. Depression and chronic pain in the elderly: links and management challenges. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;21(12):709–20.

Hunot V, Moore THM, Caldwell D, Davies P, Jones H, Lewis G, Churchill R. Mindfulness-based “third wave” cognitive and behavioral therapies for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;8(9):CD008704.

Beck JS. Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond. 2nd ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2011. p. 19–20.

Vallury KD, Jones M, Oosterbroek C. Computerized cognitive behavior therapy for anxiety and depression in rural areas: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(6):e139.

Lamb SE, Mistry D, Lall R, et al. Back Skills Training Trial Group. Group cognitive behavioral interventions for low back pain in primary care: extended follow-up of the Back Skills Training Trial (ISRCTN54717854). Pain. 2012;153(2):494–501.

Ost LG. Efficacy of the third wave of behavioral therapies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46(3):296–321.

Barone Gibbs B, Hergenroeder AL, Perdomo SJ, Kowalsky RJ, Delitto A, Jakicic JM. Reducing sedentary behaviour to decrease chronic low back pain: the stand back randomised trial. Occup Environ Med. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2017-104732.

Chehadi O, Rusu AC, Konietzny K, Schulz E, Köster O, Schmidt-Wilcke T, Hasenbring MI. Brain structural alterations associated with dysfunctional cognitive control of pain in patients with low back pain. Eur J Pain. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1159.

Rutledge T, Atkinson JH, Chircop-Rollick T, D’Andrea J, Garfin S, Patel S, Penzien DB, Wallace M, Weickgenant AL, Slater M. Randomized controlled trial of telephone-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy versus supportive care for chronic back pain. Clin J Pain. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000555.

Motoya R, Otani K, Nikaido T, Ono Y, Matsumoto T, Yamagishi R, Yabuki S, Konno SI, Niwa SI, Yabe H. Short-term effect of back school based on cognitive behavioral therapy involving multidisciplinary collaboration. Fukushima J Med Sci. 2017;63(2):81–9.

Arden K, Fatoye F, Yeowell G. Evaluation of a rolling rehabilitation programme for patients with non-specific low back pain in primary care: an observational cohort study. J Eval Clin Pract. 2017;23(2):272–8.

Cherkin DC, Anderson ML, Sherman KJ, Balderson BH, Cook AJ, Hansen KE, Turner JA. Two-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial of mindfulness-based stress reduction vs cognitive behavioral therapy or usual care for chronic low back pain. JAMA. 2017;317(6):642–4.

Ogston JB, Crowell RD, Konowalchuk BK. Graded group exercise and fear avoidance behavior modification in the treatment of chronic low back pain. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil. 2016;29(4):673–84.

Turner JA, Anderson ML, Balderson BH, Cook AJ, Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC. Mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic low back pain: similar effects on mindfulness, catastrophizing, self-efficacy, and acceptance in a randomized controlled trial. Pain. 2016;157(11):2434–44.

Reme SE, Tveito TH, Harris A, Lie SA, Grasdal A, Indahl A, Brox JI, Tangen T, Hagen EM, Gismervik S, Ødegård A, Fryland L, Fors EA, Chalder T, Eriksen HR. Cognitive interventions and nutritional supplements (The CINS Trial): a randomized controlled, multicenter trial comparing a brief intervention with additional cognitive behavioral therapy, seal oil, and soy oil for sick-listed low back pain patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016;41(20):1557–64.

Zgierska AE, Burzinski CA, Cox J, Kloke J, Stegner A, Cook DB, Singles J, Mirgain S, Coe CL, Bačkonja M. Mindfulness meditation and cognitive behavioral therapy intervention reduces pain severity and sensitivity in opioid-treated chronic low back pain: pilot findings from a randomized controlled trial. Pain Med. 2016;17(10):1865–81.

Lindgreen P, Rolving N, Nielsen CV, Lomborg K. Interdisciplinary cognitive-behavioral therapy as part of lumbar spinal fusion surgery rehabilitation: experience of patients with chronic low back pain. Orthop Nurs. 2016;35(4):238–47.

Rolving N, Nielsen CV, Christensen FB, Holm R, Bünger CE, Oestergaard LG. Preoperative cognitive-behavioral intervention improves in-hospital mobilisation and analgesic use for lumbar spinal fusion patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;20(17):217.

Monticone M, Ambrosini E, Rocca B, Cazzaniga D, Liquori V, Foti C. Group-based task-oriented exercises aimed at managing kinesiophobia improved disability in chronic low back pain. Eur J Pain. 2016;20(4):541–51.

Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, Balderson BH, Cook AJ, Anderson ML, Hawkes RJ, Hansen KE, Turner JA. Effect of mindfulness-based stress reduction vs cognitive behavioral therapy or usual care on back pain and functional limitations in adults with chronic low back pain: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(12):1240–9.

Magalhães MO, Muzi LH, Comachio J, Burke TN, Renovato França FJ, Vidal Ramos LA, Leão Almeida GP, de Moura Campos Carvalho-e-Silva AP, Marques AP. The short-term effects of graded activity versus physiotherapy in patients with chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Man Ther. 2015;20(4):603–9.

Pincus T, Anwar S, McCracken LM, McGregor A, Graham L, Collinson M, McBeth J, Watson P, Morley S, Henderson J, Farrin AJ, OBI Trial Management Team. Delivering an Optimised Behavioural Intervention (OBI) to people with low back pain with high psychological risk; results and lessons learnt from a feasibility randomised controlled trial of Contextual Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CCBT) vs. Physiotherapy. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16(16):147.

Guck TP, Burke RV, Rainville C, Hill-Taylor D, Wallace DP. A brief primary care intervention to reduce fear of movement in chronic low back pain patients. Transl Behav Med. 2015;5(1):113–21.

Monticone M, Ambrosini E, Rocca B, Magni S, Brivio F, Ferrante S. A multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme improves disability, kinesiophobia and walking ability in subjects with chronic low back pain: results of a randomised controlled pilot study. Eur Spine J. 2014;23(10):2105–13.

Khan M, Akhter S, Soomro RR, Ali SS. The effectiveness of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) with general exercises versus general exercises alone in the management of chronic low back pain. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2014;27(4 Suppl):1113–6.

Monticone M, Ferrante S, Rocca B, Baiardi P, Farra FD, Foti C. Effect of a long-lasting multidisciplinary program on disability and fear-avoidance behaviors in patients with chronic low back pain: results of a randomized controlled trial. Clin J Pain. 2013;29(11):929–38.

Finan PH, Burns JW, Jensen MP, Nielson WR, Kerns RD. Pain coping but not readiness to change is associated with pretreatment pain-related functioning. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(8):687–92.

Macedo LG, Latimer J, Maher CG, Hodges PW, McAuley JH, Nicholas MK, Tonkin L, Stanton CJ, Stanton TR, Stafford R. Effect of motor control exercises versus graded activity in patients with chronic nonspecific low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Phys Ther. 2012;92(3):363–77.

Sanderson KB, Roditi D, George SZ, Atchison JW, Banou E, Robinson ME. Investigating patient expectations and treatment outcome in a chronic low back pain population. J Pain Res. 2012;5:15–22.

Newcomer KL, Vickers Douglas KS, Shelerud RA, Long KH, Crawford B. Is a videotape to change beliefs and behaviors superior to a standard videotape in acute low back pain? A randomized controlled trial. Spine J. 2008;8(6):940–7.

Smeets RJ, Beelen S, Goossens ME, Schouten EG, Knottnerus JA, Vlaeyen JW. Treatment expectancy and credibility are associated with the outcome of both physical and cognitive-behavioral treatment in chronic low back pain. Clin J Pain. 2008;24(4):305–15.

Johnson RE, Jones GT, Wiles NJ, Chaddock C, Potter RG, Roberts C, Symmons DP, Watson PJ, Torgerson DJ, Macfarlane GJ. Active exercise, education, and cognitive behavioral therapy for persistent disabling low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(15):1578–85.

Reid MC, Otis J, Barry LC, Kerns RD. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic low back pain in older persons: a preliminary study. Pain Med. 2003;4(3):223–30.

Lang E, Liebig K, Kastner S, Neundörfer B, Heuschmann P. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation versus usual care for chronic low back pain in the community: effects on quality of life. Spine J. 2003;3(4):270–6.

Walsh DA, Radcliffe JC. Pain beliefs and perceived physical disability of patients with chronic low back pain. Pain. 2002;97(1–2):23–31.

Hasenbring M, Ulrich HW, Hartmann M, Soyka D. The efficacy of a risk factor-based cognitive behavioral intervention and electromyographic biofeedback in patients with acute sciatic pain. An attempt to prevent chronicity. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1999;24(23):2525–35.

Newton-John TR, Spence SH, Schotte D. Cognitive-behavioral therapy versus EMG biofeedback in the treatment of chronic low back pain. Behav Res Ther. 1995;33(6):691–7.

Lindström I, Ohlund C, Eek C, Wallin L, Peterson LE, Nachemson A. Mobility, strength, and fitness after a graded activity program for patients with subacute low back pain. A randomized prospective clinical study with a behavioral therapy approach. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1992;17(6):641–52.

Turner JA, Clancy S, McQuade KJ, Cardenas DD. Effectiveness of behavioral therapy for chronic low back pain: a component analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1990;58(5):573–9.

Cohen MJ, Heinrich RL, Naliboff BD, Collins GA, Bonebakker AD. Group outpatient physical and behavioral therapy for chronic low back pain. J Clin Psychol. 1983;39(3):326–33.

Nouwen A. EMG biofeedback used to reduce standing levels of paraspinal muscle tension in chronic low back pain. Pain. 1983;17(4):353–60.

Bush C, Ditto B, Feuerstein M. A controlled evaluation of paraspinal EMG biofeedback in the treatment of chronic low back pain. Health Psychol. 1985;4(4):307–21.

Abbott AD, Tyni-Lenné R, Hedlund R. Early rehabilitation targeting cognition, behavior, and motor function after lumbar fusion: a randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2010;35(8):848–57.

Brox JI, Sørensen R, Friis A, Nygaard Ø, Indahl A, Keller A, Ingebrigtsen T, Eriksen HR, Holm I, Koller AK, Riise R, Reikerås O. Randomized clinical trial of lumbar instrumented fusion and cognitive intervention and exercises in patients with chronic low back pain and disc degeneration. Spine. 2003;28(17):1913–21.

Esmer G, Blum J, Rulf J, Pier J. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for failed back surgery syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2010;110(11):646–52.

Morone NE, Greco CM, Weiner DK. Mindfulness meditation for the treatment of chronic low back pain in older adults: a randomized controlled pilot study. Pain. 2008;134(3):310–9.

Morone NE, Rollman BL, Moore CG, Li Q, Weiner DK. A mind-body program for older adults with chronic low back pain: results of a pilot study. Pain Med. 2009;10(8):1395–407.

Zgierska AE, Burzinski CA, Cox J, Kloke J, Singles J, Mirgain S, Stegner A, Cook DB, Bačkonja M. Mindfulness meditation-based intervention is feasible, acceptable, and safe for chronic low back pain requiring long-term daily opioid therapy. mindfulness meditation-based intervention is feasible, acceptable, and safe for chronic low back pain requiring long-term daily opioid therapy. J Altern Complement Med. 2016;22(8):610–20.

Huang H, Wolf SL, He J. Recent developments in biofeedback for neuromotor rehabilitation. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2006;21(3):11.

Giggins OM, Persson UM, Caulfield B. Biofeedback in rehabilitation. J Neuroeng Rehabil. 2013;18(10):60.

Fordyce WE, Mosby CV. Behavioral methods for chronic pain and illness. Pain. 1977;3(3):291–2.

Morley S. Efficacy and effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy for chronic pain: progress and some challenges. Pain. 2011;152(3 Suppl):S99–106.

Moore JE. Chronic low back pain and psychosocial issues. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2010;21(4):801–15.

Walsh DA, Radcliffe JC. Pain beliefs and perceived physical disability of patients with chronic low back pain. Pain. 2002;97(1–2):23–31.

Linton SJ. A review of psychological risk factors in back and neck pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(9):1148–56.

Foster NE, Thomas E, Bishop A, Dunn KM, Main CJ. Distinctiveness of psychological obstacles to recovery in low back pain patients in primary care. Pain. 2010;148(3):398–406.

Oliveira VC, Furiati T, Sakamoto A, Ferreira P, Ferreira M, Maher C. Health locus of control questionnaire for patients with chronic low back pain: psychometric properties of the Brazilian–Portuguese version. Physiother Res Int. 2008;13(1):42–52.

Macedo LG, Smeets RJ, Maher CG, Latimer J, McAuley JH. Graded activity and graded exposure for persistent nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review. Phys Ther. 2010;90(6):860–79.

Brox JI, Nygaard ØP, Holm I, Keller A, Ingebrigtsen T, Reikerås O. Four-year follow-up of surgical versus non-surgical therapy for chronic low back pain. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(9):1643–8.

Call-Schmidt TA, Richardson SJ. Prevalence of sleep disturbance and its relationship to pain in adults with chronic pain. Pain Manag Nurs. 2003;4(3):124–33.

Zarrabian MM, Johnson M, Kriellaars D. Relationship between sleep, pain, and disability in patients with spinal pathology. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2014;95(8):1504–9.

Manber R, Edinger JD, Gress JL, San Pedro-Salcedo MG, Kuo TF, Kalista T. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia enhances depression outcome in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder and insomnia. Sleep. 2008;31(4):489–95.

Linton SJ. A review of psychological risk factors in back and neck pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(9):1148–56.

Edwards RR, Cahalan C, Mensing G, Smith M, Haythornthwaite JA. Pain, catastrophizing, and depression in the rheumatic diseases. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7(4):216–24.

Smeets RJ, Vlaeyen JW, Kester AD, Knottnerus JA. Reduction of pain catastrophizing mediates the outcome of both physical and cognitive- behavioral treatment in chronic low back pain. J Pain. 2006;7(4):261–71.

Bishop SR, Lau M, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson ND, Carmody J, Segal ZV, Abbey S, Speca M, Velting D, Devins G. Mindfulness: a proposed operational definition. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2004;11:230–41.

Dahl J, Wilson KG, Nilsson A. Acceptance and commitment therapy and the treatment of persons at risk for long-term disability resulting from stress and pain symptoms: a preliminary randomized trial. Behav Ther. 2004;35:785–801.

Veehof MM, Oskam MJ, Schreurs KM, Bohlmeijer ET. Acceptance-based interventions for the treatment of chronic pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain. 2011;152(3):533–42.

Godfrey E, Galea Holmes M, Wileman V, McCracken L, Norton S, Moss-Morris R, Pallet J, Sanders D, Barcellona M, Critchley D. Physiotherapy informed by Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (PACT): protocol for a randomised controlled trial of PACT versus usual physiotherapy care for adults with chronic low back pain. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e011548.

Turk DC. The potential of treatment matching for subgroups of patients with chronic pain: lumping versus splitting. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:44–55.

Vlaeyen JWS, Morley S. Cognitive-behavioral treatments for chronic pain: what works for whom? Clin J Pain. 2005;21:1–8.

Acknowledgements

This is a summary of independent research carried out at the NIHR Sheffield Biomedical Research Centre (Translational Neuroscience). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health. Dr. Zis is sincerely thankful to the Ryder Briggs Fund.

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published.

Disclosures

Kristallia Vitoula, Annalena Venneri, Giustino Varrassi, Antonella Paladini, Panagiota Sykioti, Joy Adewusi, and Panagiotis Zis have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article, go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.6121151.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Vitoula, K., Venneri, A., Varrassi, G. et al. Behavioral Therapy Approaches for the Management of Low Back Pain: An Up-To-Date Systematic Review. Pain Ther 7, 1–12 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-018-0099-4

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40122-018-0099-4