Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) more than any other neurological disorder has experienced a tremendous progress in available evidence-based innovator disease modifying therapies (DMT). These medications include injectable complex nonbiological drugs (CNBD), the injectable biological products β-interferons-1a and -1b, and the infusible monoclonal antibodies (MAB), as well as oral synthetic therapeutic molecules. The degree of efficacy and adverse effects profile is variable. By the end of 2019, all medications have been approved for relapsing forms of MS, including five with indication for clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), two for active secondary progressive MS, and one for primary progressive MS. With the advent of the first generation or “platform” injectable DMT in the 1990s the cost of MS care increased substantially driven basically by the cost of these therapies. As new drugs licensed by health agencies appeared in the global market, the cost of these agents notably increased augmenting the economic gravamen of disease particularly in North America This industrial phenomenon has been promoted by the remarkable profits obtained by the biopharmaceutical companies producing these medications, costs increasing about seven times per patient per year in the span of two decades. The global MS drug market was valued at US$16.3 billion in 2016, expecting to reach US$27.8 billion by 2025. The societal and economic effect of these costs constitute an international concern for health systems which adjudicate an increasing portion of financial resources to MS care. This effect has had a more notorious impact in emerging countries with economies in development. In the early 2000s the industry producers of biosimilar molecules initiated the concept of manufacturing follow-on biosimilar therapeutic options for MS available at a reduced cost without affecting efficacy and safety. Latin American biotechnological companies from Mexico, Argentina and Uruguay, introduced into the regional markets biosimilar β-interferons. These products were licensed by the local regulatory agencies without challenging pharmacological profile and their claims of similarity with the innovator medications. In the licensing process, biosimilar manufactures have typically utilized published literature and phase III clinical trials data previously acquired by the brand medication (“third approval pathway’’). This has raised concerns among local neurological communities and patient organizations in the area. This situation is compounded by the fact that no discernible health cost savings have resulted since their introduction in Latin American countries. In some European countries where the health care system, public and private systems, regulated by Ministries of Health, negotiate with the pharmaceutical industry drug pricing and payment systems. The business scenario has stimulated local industries to produce follow-on biosimilar medications, theoretically to compete or replace the original brands. Countries such as Iran who have experienced a substantial increase in MS prevalence (101.19 per 100,000 inhabitants) has enabled their national Food and Drug Organization (FDO) to license locally produced biosimilar interferon 1-a and 1-b based on somewhat limited clinical studies. The Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, approved the first biosimilar β-interferon-1a (44 mcg subcutaneous administration) manufactured in the country and developed in accordance to the guidelines of the European Medicine Agency (EMA) for phase I and phase III studies. The EMA, however, along with other international licensing agencies: United States Food and Drug Agency (FDA), Health Canada, the Japanese Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHPRA), and others, have produced strict guidelines regulating registration of biosimilar medicines. Thus far these agencies have not approved any interferon or MAB for MS based on these principles. The main obstacles for the approval of biosimilar medications by international health agencies is their consistent inability to demonstrate therapeutic equivalence through physiochemistry, biology, immunogenicity aspects, molecular behavior and clinical studies, preferably through a controlled phase III study, or ideally, utilizing a comparative head-to-head trial with the innovator. Recommendations proposed by experts from the Latin American region to guarantee production quality of biosimilar products, efficacy and safety, include strict application of current regulations; avoid uncontrolled interchangeability; implement strong pharmacovigilance; educate healthcare professionals and regulatory officials on the different issues involved in the biosimilarity concept and use evidence-based decision for therapy selection. The main priority should always be the protection and well-being of the patient irrespectively of therapy availability or pharmacoeconomic issues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Commentary

Advance in knowledge on the multifactorial mechanism contributing to the development of MS has consequently reflected in progress developing therapies addressing the increasing identification of molecular mechanisms of disease. This has resulted in a tremendous impact in the natural evolution of disease. The advent in 1993 of the first bonafide specific biological disease modifying therapy (DMT) for MS, β-interferon-1b, initiated the epoch of designed targeted molecular pathways and specific treatments for the disease. By the end of 2019, 14 unique molecules providing pharmacological basis to 20 different products licensed by international health agencies, constitute the therapeutic armamentarium potentially available for management of relapsing and progressive MS. This is a remarkable scientific and industrial achievement, which has been more notorious in the MS field than in other neurological discipline. Licensing medications by health agencies is based on results on efficacy and safety procured from phase I and II studies, culminating with large placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized, phase III studies. This modern design for MS therapy clinical trials starting in the 1990s became the standard approach for studies to come, including (with some updates and amendments, i.e., incorporation of active comparator) the most recent studies performed in the actual era resulting in the approval of more modern and advanced DMT.

In general, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medicines Agency (EMA) are the regulatory institutions possessing the more effective resources to advice, assess and provide appropriate warnings and contraindications on the drug proposed for approval before is released to the public, along with post-marketing safety surveillance. Other European regulatory agencies counting with adequate evaluatory resources, functioning independently from EMA, but maintaining effective interaction, include the United Kingdom Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA), and the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Australia, Canada and Japan, all have active regulatory offices. Practically every industrialized and country-in-development in the world include at present in their national health system a department, office, or agency on charge of regulatory approval of medicines. Each country’s health program has a different design and is governed by a national legal framework. Theoretically, an ideal licensing acquisition would be that each proposed medication presented by the developer or the manufacturing company to the responsible authorities, should provide significant efficacy and safety results based on evidence, obtained through appropriate basic studies and well-designed clinical controlled trials. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Industrial and Scientific Divergent Missions

The main professional and scientific motivations of researchers and clinical investigators contributing to pre-approval, pre-marketing studies and investigational efforts, are directed to develop increasingly sophisticated and efficacious MS therapies to eventually translate into options for practitioners to treat their patients in the real world. On the other hand, the motivation of the pharmaceutical industry supporting therapeutic development and research is targeted towards the potential commercial possibilities and profitability. The elevated cost of these medications enabled by market tolerance and loose national and international legislative control, has been an issue provoking considerable discussion and societal concern.

The first DMT generation, also called platform therapies, are all injectable drugs: subcutaneous β-interferon-1b (approved in 1993); intramuscular β-interferon-1a (1995); subcutaneous glatiramer acetate (1997), and subcutaneous β-interferon-1a (2002). From 1993 to 2014, the price paid by Medicaid (US health coverage for low-income and disabled individuals, administered by stat es, according to federal requirements) increased from US$9000 to US$60,000 per patient per year. The prices paid by another US health institution, the Veterans Administration System, started lower and increased lower than those paid by Medicaid over the course of this epoch. DMT prices paid in Canada, Australia and the United Kingdom are lower than Medicaid prices [1].

The global MS drug market was valued at US$16.3 billion in 2016, and is expected to reach US$27.8 billion by 2025 expanding at a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 6.3% from 2017 to 2025. North America holds the largest MS drugs market share [2]. These earnings estimations apply strictly to innovator brand medications, and include all medications licensed up to 2016: the four injectable platform therapies, three oral agents, a pegylated subcutaneous 13-interferon-1a, and two infusible “second-line or third-line” monoclonal antibodies (MAB). Except for glatiramer acetate and the oral molecules approved for relapsing MS (RMS) during this interval (fingolimod, teriflunomide and dimethyl fumarate), the rest, one β-interferon-1b (250 mcg by subcutaneous injection every-other-day) and β-interferon-1a (30 mcg weekly intramuscular injection or 44 mcg subcutaneous inject ion three times a week), the MAB natalizumab (anti-cell adhesion molecule a4-integrin), and alemtuzumab (anti-CD52), are innovator biological products.

Most recent MS drugs entering the therapeutic scenario: ocrelizumab (2017), siponimod and cladribine (2019) are not included in the above cost appreciation. Ocrelizumab is a biological anti-CD20 B-cell inhibitor MAB with indications in RMS and the first agent approved for primary progressive MS [3].

Siponimod (S1P1 receptor modulator) and cladribine (nucleoside metabolic inhibitor) are synthetic molecules with the novel indication for active secondary MS, defined as progressive course with clinical relapses, presence of T1 gadolinium enhancing MRI lesions, and/or new or enlarging T2 MRI lesions [4].

Siponimod is also indicated for clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) and RMS [5]. Cladribine is approved as second-line therapy, but not for CIS [6].

International Impact of Biosimilar Follow-on Medications

The compelling business scenario forecast by the pharmaceutical industry encouraged the entrance into the market competition biosimilar producers, focusing initially on interferon production.

In 2004 a Mexican biopharmaceutical enterprise obtained access to the Mexican health institutional and public markets for the first biosimilar β-interferon-1b for MS, follow-on of the brand innovator licensed since 1993. Despite the attractive premise of providing a less expensive, but equally effective and safe product as the innovator medication, local patients support groups and neurologists raised concerns regarding the replacement of the original medication, considering that many patients, particularly beneficiaries of the Mexican Institute of Social Security, were already been treated with the innovator interferon [7]. This concern was compounded by the absence of data from phase I-III studies not available from the proposed new MS product.

Latin America is one of the regions where the advent of biosimilar drugs for MS have exerted a notable impact, not just in the market share, but as integral part of pharmacological products available in the institutional pharmacy formularies in many of the countries of the area. At present there are nine follow-on β-interferon formulations replacing or competing with the three-interferon innovator products [8]. Thus far, the only other biosimilar product which was temporarily available as an anti-CD20 B-cell inhibitor MAB competing directly with Rituximab, was a Mexican product, which was removed from the market in 2014 due to litigation arguing intellectual property rights and lack of clinical studies [9]. Rituximab, despite studies showing efficacy in RMS [10], has not been approved by the FDA for this indication although it is often prescribed off-label. Rituximab is internationally licensed for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia and granulomatosis with polyangiitis.

The advent of biosimilar medications in Latin America has been enabled by the effective marketing and distribution of follow-on interferons for MS by several Mexican and Argentinean and one Uruguayan biopharmaceutical companies. Except for a few instances, the approval process of these products have proceeded for the most part unchallenged by the licensing agencies in the region, regardless of the patent status viability of the brand product.

Typically, since biosimilar interferons do not possess their own clinical studies, the companies applying for medicine registration have utilized the extensive data previously obtained by the innovator through their controlled phase Ill clinical trials. In fact, in most cases, the respective package inserts (regulatory prescribing information) read almost verbatim. In this context, regulatory agencies from Latin American countries have adopted the “third approval pathway” granting approval to biosimilars based on literature references from the innovator. If molecular similarity comparable data is provided supporting the follow-on molecule licensing application, data from their own clinical trials are not required. Only five Latin American countries (Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Panama and Venezuela) have health legalization limiting approval of biosimilars if clinical data are not available. An excellent recent paper (Neurology and Therapy, May 2019) [11] addresses practical issues concerning the approval and use of biosimilar drugs for the treatment of multiple sclerosis in Latin America. The study emphasizes the need for regulation, risk management, and pharmacovigilance of these products on the American continent. Increasing prevalence of MS in the world has stimulated local industries to produce follow-on biosimilar medications theoretically to compete (or replace) the original expensive brands manufactured elsewhere. An example of this effort is reflected in Iran, where the frequencies of disease have increased notoriously in recent years. The most recent epidemiologic study showed a prevalence in the Tehran’s area of 101.39 per 100,000 Inhabitants [12]. A small study comparing head-to-head the efficacy and side effects of a weekly intramuscular Iranian version of β-interferon-1a (CinnoVex®) with the brand molecule, disclosed no differences [13]. The Iranian Food and Drug Organization (FDO) licensed this product. The FDO enforces the national pharmaceutical laws as the health department on charge of licensing medicines, and by utilizing preliminary studies, it has approved another nationally-produced biosimilar 13-interferon-1b [14], which is used thus far in limited and on investigational basis.

While these agents are not widely distributed internationally (Iran is not a member of the World Trade Organization), CinnoVex ® has been available in Russia since 2010 after the “Seven Diseases” (Orphan Diseases) Federal Program provided free medications for MS patients living in Moscow. The public and Russian neurological communities, however, have been wary on a perceived reduced efficacy and side effects experienced with foreign-produced biosimilar interferon medications. A study based on patient-event reporting in a Moscow’s cohort comparing CinnoVex® with another biosimilar interferon-1a (subcutaneous Genfaxon®44 mcg) produced by an Argentinean company, disclosed high frequency treatment withdrawal due to perceived clinical failure and subjective intolerance [15]. The Russian government has encouraged local enterprises (i.e., Biocad) to enter the biosimilar industry scenario. These efforts encompass the production of other therapeutic biologicals including the MAB Rituximab indicated in this case strictly for hematologic malignancies and registered in 2014. The Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation licensed in 2017 the first biosimilar β-interferon-1a, 44 mcg by subcutaneous injection three times a week, produced by Biocad. This is the only MS biosimilar product registered in Russia and worldwide developed in accordance with the EMA guidelines.

Reportedly, no statistically meaningful differences in pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD) In phase I studies were detected, while safety and efficacy equivalence to the reference medicine in phase III trials were found. Phase I and II studies are being conducted for a pegylated form of interferon by Biocad [16].

International licensing agencies, FDA, EMA, Health Canada, the Japanese PMDA (Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency), the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency, and others, have produced strict guidelines for approval of biosimilar medicines (including 13-interferons for MS) requiring rigorous preclinical studies, comparable PK and PD with the reference product, and a randomized, controlled, phase III clinical study. In MS trials the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS), other measurements of neurological performance, and MRI parameters must be included in the trial. In theory, for biosimilar medications efficacy and safety should be demonstrated to be at least comparable, “non-inferior” to the innovator. Thus far, these organizations have not approved biosimilars for MS. These guidelines do not apply to NBCD and copies of laboratory synthesized molecules demonstrating bioequivalence. Clinical trials in these cases are not required.

Challenges Posed to Biosimilar Medications

The attractive alternative of biosimilar medications affecting positively pharmacoeconomic aspects of MS care, from diagnosis to management, has not crystalized. While costs are driven mostly by the price of medicines, tangible and intangible costs confound the economic burden. Except for a few cases the advent of biosimilar medications for MS has not impacted the economy of taking care of MS. Because of their consistent approval in emergent countries, market tolerance and business vocation, the follow-on molecules have in fact competed effectively with the brand products. In most cases, the savings to health systems have been only nominal or symbolic. The major hindrances for wider acceptance of these formulations remain the absence of appropriate studies supporting their production quality and justification for utilization. Except for the Russian products that apparently have satisfied regulatory guidelines, the immense majority, if not all biosimilar β-interferons for MS offered in Latin America and other areas of the world, lack these essential data.

In the Iranian case, national pharmaceutical companies do not have access to the same complex manufacturing processes as those used for producing originators including cell cultures, fermentation and purification procedures. Studies utilizing reverse-phase liquid chromatography coupled with proteomic technology using mass spectrometry analysis applying to a Mexican version of β-interferon-1b compared with the innovator, demonstrated glycation of the follow-on product, not detected in the brand medication. The investigators felt this structural chemical change would potentially lead to different PD and PK profiles affecting safety [17]. The clamor of similarity is not sustainable in these cases. Some investigators feel these follow-on medications in fact should be considered as new products, hence they should be proposed utilizing a New lnvestigational Drug (IND) application [18].

Other molecular differences have been found by diverse techniques. Chemical aggregates to the composition of the biosimilar agent favor diminution pharmacological potency, inconsistent biological activity from batch to batch, and potential to increase risk of immunogenicity and development of neutralizing antibodies (NABs) [19, 20].

Failure to demonstrate equivalence and lack of clinical evidence from biosimilar products have been carefully studied issues for almost two decades resulting in these proposed medicines for MS not being considered or included in current international therapeutic guidelines [21,22,23,24,25].

Final Considerations

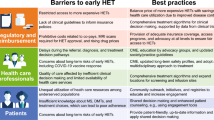

Biosimilar medications for MS including β-interferons and MAB offer an industrial and commercial opportunity to impact the accelerating costs of disease. This premise has not reflected in real-life expectations particularly in the Latin American region [26]. In countries where the national health care systems negotiates drug prices with the pharmaceutical industry, the savings are substantial. Biosimilar products need to resolve the same licensing regulatory challenges that innovators face. Except for a few cases manufacturers have adhered to internationally established guidelines. The Latin American study group [11] emphasizes the need for implementation of current regulations to be applied to the registration of biosimilar drug products. The group proposes adequate national and multinational studies in the region to demonstrate similarity along with a strict post-marketing pharmacovigilance program. An international consensus would help to disseminate neurological and community information and expectations regarding these concerns. Essential to accomplish effectively these goals imply education of health professionals and officials responsible for the licensing processes. The patient’s well-being and safety remain as the fundamental principles in treating MS.

References

Hartung DM, Bourdette DN, Ahmed SM, et al. Neurology. 2015;84(21):2185–92.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS) drugs-global market projections to 2023: Key players are bayer, Biogen, Merck, Novartis, and Sano fi-Resear chAndMark ets.com (Published Mar 22, 2019). Press Release. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20190320052014/en/. Accessed 23 June 2019.

https://www.ocrevus.com. Accessed 23 June 2019.

Lublin F, Reingold SC, Cohen JA, et al. Defining the clinical course of multiple sclerosis. The 2013 revisions. Neurology. 2014;83:278–86.

http://www.nationalmssociety.org/ Treating-MS/Medicat ions/Mayzant. Accessed 23 June 2019.

http://www.fda.gov/new-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-neworal-treatment-multiple-sclerosis. Accessed 23 June 2019.

Rivera VM, Medina MT, Duron RM, et al. Multiple sclerosis care in latin America. Neurology. 2014;82(18):1660–1.

Skromne E, Ordonez L, Trevino-Frenk I. Disease modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis in latin America. MSJ-ETC 2017:1–8.

Sanitary Alert (Cofepris-Mexican Federal Commission for the Protection Against Sanitary Risks- revokes registration of the product “Kikuzubam”. 28 March 2014 https://www.gob.mx (accessed 23 June 2019).

He D, Guo R, Zhang E, et al. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 912:CD009130.pub3.

Steinberg J, Fragoso YD, Duran Quiroz JC, et al. Neurol Ther 2019 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-019-0139-y.

Eskandarich S, Heydarpour P, Sahralan MA. Prevalence and incidence of multiple sclerosis in Tehran, Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2017;46(5):699–704.

Nafissi S, Azimi A, Amini-Harandi A, et al. Comparing efficacy and side effects of weekly intramuscular biogeneric/biosimilar interferon beta-la with Avonex in relapsing-remit t ing multiple sclerosis: a double blind randomized clinical trial. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114:986–9.

Rahimi F, Rasekh HR, Abbasian E, et al. Patient preferences for interferon-beta in Iran: a discrete choice experiment. PLoS One 2018; https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone0193090.

Borets OG, Davydovskaya MV, Demina TL, et al. Experience in the use of the!3-lnterferon-la biosimilars CinnoVex and Genfaxon 44 at the Moscow city multiple sclerosis center. Neurosci Behav Physiol 2017;47(1):107–111.

http://www.gabionline.net/Biosimilars/News/Russian-approvaI-for-non-originator-interferon-beta-la. Accessed 23 June 2019.

Lin L. Betseron. Dev Biol Stand. 1998;96:97–104.

Rivera VM, Macias MA. Access and barriers to MS care in Latin America. MSJ- ETC 2017: 1–7 https://doi.org/10.1177/20155217317700668.

Meager A, Dolman C, Dilger P, et al. An assessment of biological potency and molecular characteristics 31of different innovator and noninnovator interferon-beta products. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011;31(4):383–92.

Farrell RA, Marta M, Gaeguta AJ, et al. Development of resistance to biologic therapies with reference to IFN-!3. Rheumatology. 2012;51(4):590–9 (tinP://rheumatology.oxfordjournals.org).

Ghezzi A. European and American guidelines for multiple sclerosis treatment. Neurol Ther 2018;7(2):189-194.

Practice Guidelines Systematic Review Summary (American Academy of Neurology): Disease-modifying Therapy for Adults with Multiple Sclerosis. April 2018 https://www.aan.com/Guidelines/home/By/Topic?topic,d=18.

The use of disease-modifying therapies in multiple sclerosis: principles and current evidence. MS coalition. www.nationa.lmssociety.org.

Montalban X, Gold R, Thompson AJ, et al. ECTRIM S/EAN Guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. MSJ-ETC. 2018;24(2):96–120.

Abad P, Nogales-Gaete J, Rivera V, et al. Documento de Consenso de LACTRIMS para el Tratamiento Farmacologico de la Esclerosis Multiple y sus Variant es Clinicas. [Treatment Consensus of Multiple Sclerosis from the Latin American Committee for Treatment and Research in M S-LACTRIMS]. Rev Neurol 2012;55(12):737–748.

Rivera VM. Multiple sclerosis: a global concern with multiple challenges in an era of advanced therapeutic complex molecules and biological medicines. Biomedicines. 2018;6:112. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines6040112.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Victor M. Rivera has nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.8567822.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rivera, V.M. Biosimilar Drugs for Multiple Sclerosis: An Unmet International Need or a Regulatory Risk?. Neurol Ther 8, 177–184 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-019-0145-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-019-0145-0