Abstract

The need for patient-centered care has become a focal point of healthcare improvement initiatives. Shared decision making—in which patients and clinicians communicate about various treatment options and goals and patient input is considered when making treatment decisions—has been associated with improved health and quality of life. A method of treatment evaluation allowing incorporation of patient-specific goals and perspectives is of increasing interest to healthcare providers, payers, and patients. An approach that allows incorporation of shared goal setting is possible via use of an instrument called the Goal Attainment Scale (GAS). This scale provides the structure for measuring progress toward treatment goals set through patient–clinician collaboration. The goal attainment approach has been used as a primary outcomes measure in numerous studies but not in major depressive disorder (MDD). As MDD is a complex, multidimensional disorder affecting each patient differently, the use of GAS methodology is a relevant framework for setting personalized meaningful treatment goals. Initial research into the feasibility of using the GAS in MDD (GAS-D) to measure patient-centric outcomes that may be neglected when more traditional scales are used has been encouraging. The objective of this Commentary is to provide background and rationale for implementation of the GAS-D in clinical practice.

Funding Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd., and Lundbeck LLC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Patient-Centered Care

Clinical practice has been increasingly focused on incorporation of the patient voice. This has led to the need to develop assessments that more closely capture outcomes that are relevant to the patient, rather than simply inventories of classic symptoms. Historically, outcomes of major depressive disorder (MDD) have been evaluated using standardized clinician rating scales, such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) or the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) [1, 2]. Because these measures are traditional symptom inventories assessing fixed constructs, such as sadness, sleep difficulty, anhedonia, or pessimistic/suicidal thoughts, they may not capture the most meaningful outcomes from the perspective of individual patients. Each patient is likely to have a different perspective on which symptomology is most troublesome and what represents treatment success. The focus of this paper is to describe the rationale and development of a more specific, patient-tailored instrument for depression, namely, the adaptation of the Goal Attainment Scale (GAS) for depression, the GAS-D. Data supporting this development have been published elsewhere and are reviewed within this Commentary. This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

The evolution of personalized medicine, namely, a medical model based on tailoring a therapeutic strategy to the characteristics of an individual at the time of treatment [3], has resulted in changes in the clinical encounter. While one component of personalized care may focus on a patient’s physiological or genetic characteristics to guide treatment selection, other aspects of personalized care might involve a more holistic approach to a patient’s situation. As part of continuous improvement in health care, clinicians are endeavoring to more actively involve their patients and families in decisions about their care to achieve outcomes desired by the patient, focusing on treatment effectiveness and achieving what the patient considers to be a meaningful outcome [4]. This approach is actively supported in the current climate, where organizations such as the European Union (and individual member countries), the World Health Organization, and the Institute of Medicine recommend that healthcare providers (HCPs) practice patient-centered care [3, 5,6,7]. Increased patient engagement with shared decision making between the patient and clinician is associated with better patient experience, health, and quality of life, and better economic outcomes [1, 7, 8]. In addition, a recent guidance document issued by the Food and Drug Administration recommends consideration of patients’ perspectives in the overall benefit–risk profile for treatments and in the decision-making process before product approvals [9]. These guidance documents highlight the need for patient-centered care. Conversation between the patient and clinician should be encouraged above and beyond the simple provision of information and options [10].

However, delivering patient-centered care also requires training and a formal framework to be effective [8]. Although patient-centered care starts at a systems level, it is important to cultivate a culture that encourages HCP–patient communication, engagement of patients in the treatment decision-making process, and the assessment of treatment outcomes using both patient-reported and clinical measures [11]. Furthermore, eliciting patients’ preferences and values can be difficult, variable across time, and influenced by the methodology used to assess those preferences and values.

Current Outcome Measures for MDD: Patient vs Clinician Assessment of Remission

MDD spans multiple domains of functioning; patients experience emotional, physical, and cognitive symptoms [12]. MDD affects more than 300 million individuals globally, and its impact is burdensome. Worldwide, it is the leading cause of disability [13].

A focus of MDD treatment has been on achieving remission, with recovery from all symptoms [14]. Approximately half of all patients with MDD do not respond to first-line antidepressants [15]. Even among those who do experience some relief or remission from depressive symptoms, complete remission with full functional recovery may not always be achieved with drug therapy and/or psychotherapy [14, 16].

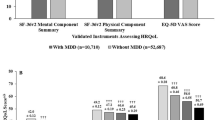

Although patients’ and clinicians’ treatment objectives may appear equivalent in that both aim for remission, or in plain English, treatment success, their definitions of remission and how remission may be measured are not equivalent [17]. Common rating scales used to define remission in a clinical trial or clinical practice setting may focus on depressive symptoms but not on a return to a pre-morbid level of functioning [18]. It is feasible that on tracking a patient’s score over time, a clinician may believe that the patient is in remission, while the patient may continue to experience a low level of symptoms and may not consider himself/herself to have achieved a full functional recovery [19, 20].

Patients consider many domains to be important in achieving remission in addition to mood-related symptoms, including features of positive mental health, coping ability, functioning, and a general sense of well-being and satisfaction with their lives [21]. Depressed patients may also cite other mental health characteristics, such as feeling like one’s normal self, when considering remission status [18]. For example, in a study in which the treatment goals of depressed outpatients were examined, researchers found that most goals related to the patients’ day-to-day functioning, including improvements in family/social relationships, increases in positive health behaviors, and finding a job or organizing their homes [22].

Given the variations in the definition of “treatment success”, flexible measures are important. A single rating scale that can capture the heterogeneity of MDD does not exist, whether it is because of insufficient item coverage or the need for certain signs, symptoms, or desired outcomes to be assessed by clinical observation, clinical interview, or patient self-report [23]. Clinicians may want to consider a broader conceptualization of functional and symptom-based outcomes to guide them in their treatment decision making [18]. The approach of shared decision making between the patient and clinician for the evaluation of progress toward remission allows flexibility in defining and measuring a successful treatment outcome.

The Goal Attainment Approach

The Goal Attainment Scale (GAS)

With the disease treatment landscape becoming more patient-centric, an individualized approach to evaluating a treatment intervention is of great interest to all healthcare stakeholders [24]. One measurement tool, the GAS, allows a patient to work jointly with his/her HCP to set up individualized treatment goals. These goals may differ from patient to patient, but the goal attainment approach offers a standardized assessment of a treatment intervention in a heterogeneous group of patients [24, 25].

The GAS was first introduced in 1968 by Kiresuk and Sherman and was intended for use in the evaluation of mental health services [26]. Since then, the GAS has been used in a broad range of healthcare and non-healthcare applications, such as mental health, education and social service, rehabilitation, randomized clinical trials in neuroscience, and geriatrics [24, 27,28,29,30].

Goal Setting and Scoring

Use of the GAS involves a semiquantitative approach, characterized by first identifying problems specific to an individual patient, and then framing these problems into goals that are specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, and time-bound (SMART) [24, 25, 31]. The HCP typically would work with his/her patient to develop treatment goals, which are then scaled using a basic evaluation design with outcomes ranging from the least to the most favorable [26]. For example, possible values may include − 2, − 1, 0, 1, and 2, where − 2 signifies baseline performance, 0 denotes targeted performance achieved, and 2 denotes outstanding goal achievement (Fig. 1) [26]. Each individual’s progress toward goal attainment can then be converted into a standardized T score [26]. This method allows for assignment of a single score for a patient with multiple goals and permits comparisons between patients and between treatment modes [26]. Thus, although GAS methodology is typically applied at an individual level to measure goal attainment, results may also be analyzed at a group level.

Scoring the Goal Attainment Scale (GAS). Collaborative goal-setting exercise as a means of tracking individual progress over time. Goals must be meaningful to the subject. Good goals are characterized by being specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time-bound. Progress is measured against equidistant benchmarks ranging from − 2 to + 2

Implementation of GAS Methodology Across Therapeutic Disciplines

Ruble et al. [27] analyzed data from two randomized clinical trials that used the goal attainment approach to assess whether a parent–teacher consultation/planning framework was effective in helping children with autism meet their educational goals. Their intention was to evaluate specific assumptions about GAS scoring, comparability across groups, and whether scores were reliable and comparable when applying different behavioral observation methods. Indeed, the researchers found that scores were reliably coded and stressed the importance of study personnel practicing goal writing and development, setting goals at study onset, and testing for goal equivalency prior to study initiation to ensure methodological quality [27].

In an exploratory pilot study, the GAS was integrated into a work-related behavioral intervention for chronically depressed individuals with persistent work dysfunction as a way to structure the treatment intervention and track progress toward desired outcomes. Examples of desired outcomes included goals relating to work or school, such as finding a job or improving productivity, as well as health-related goals, such as weight loss or taking care of medical problems [32]. For the majority of patients, improvements in work functioning and in the ability to meet social and interpersonal goals were realized, and the GAS was determined to be an appropriate tool for tracking individual progress toward predetermined goals [32].

The GAS also demonstrated utility as a primary outcome measure to assess clinically meaningful progress toward goals preset by patients/caregivers and their treating physicians in a 12-month open-label trial of donepezil hydrochloride in 108 patients with Alzheimer disease [29]. GAS scores were shown to correlate modestly with standard outcome measures. However, the authors concluded that the GAS was most valuable when incorporating patient preferences alongside other standard measures, allowing for a broader understanding of treatment benefit [29].

The responsiveness of the GAS in measuring outcomes is likely related to its design, offering greater sensitivity and covering more domains than standard measures [30]. In a randomized, double-blind trial of a specialized intervention targeted at frail, community-dwelling elderly adults, the GAS was more responsive than other standard measures of functional improvement, such as the Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) [30]. The GAS was able to detect differences in a patient’s function, safety, activity, and medication use that standard measures failed to capture [30]. Furthermore, the authors maintain that the study’s randomized, double-blind design is the strongest argument against any suggestion that the GAS may be over-responsive or measures trivial changes of little clinical importance [30].

This small sampling of applications of the GAS approach illustrates its potential for assessing patient-desired outcomes across a range of therapeutic disciplines and practical applications.

Need for Patient-Centric, Goal-Oriented Approach in MDD

Each patient with MDD tends to have a unique view of their disease severity, comorbidities, and treatment needs. Efforts to define desired treatment outcomes with patients may reveal cultural differences and the impact of any stigma associated with mental illness [33]. A patient-centered approach that incorporates the patient’s desires, values, and preferences into a personalized treatment plan encourages communication between the patient and his/her HCP and is an essential aspect of collaborative care [34, 35].

Efforts to incorporate treatment goals have been attempted in some instances of care for patients with depression, but not in a systematic manner such as the GAS-D allows. Improved clinical outcomes have been reported in the management of comorbid depression when care coaches were used to promote patient-centric self-efficacy and optimal patient care [36]. Furthermore, goal-focused interventions, such as goal setting and planning, have proven to be useful for patients with depression because they serve to increase their levels of well-being and reduce depressive symptoms [37]. In addition, in the primary care setting, there seems to be a large degree of variation in the extent to which shared decision making is experienced by depressed patients; elderly patients and those who have been in treatment for an extended amount of time (6 weeks or more) were less likely to report participation in shared decision making [35]. Certainly, compared with clinical studies of depression treatments, the opportunity for extended dialogue between the patient and clinician may be limited in clinical practice. The opportunity to utilize the GAS approach in the primary care setting should allow for a structured clinical backdrop or framework in which shared decision making can exist. With increased patient input, it is more likely that goals set will be meaningful and that even minor progress detected may be of great significance to the patient [24].

Adapting the GAS for Depression (GAS-D)

Feasibility of Using the GAS for MDD

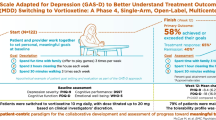

In a recent study to evaluate whether the GAS approach would be feasible in MDD, patients were surveyed using the PatientsLikeMe (PLM) platform, a patient-powered online network that allows for real-time patient input into clinical research [38]. This survey study aimed to better understand the experiences of patients with MDD in clinical goal setting and demonstrated that although patients had treatment goals, they rarely used any formal goal-setting process [39]. This study also aimed to learn about patients’ receptiveness toward the GAS approach by describing treatment goal-setting methods within various domains, providing examples, and describing how the goals would be jointly determined by patients and their clinicians, as well as how they are benchmarked and scored. An example of the GAS adapted for the subdomain relating to social functioning (Fig. 2) was also presented in order to gain feedback. In response to the example presented, patients noted that they saw value in the GAS approach because it would allow them to give input into the design of their treatment plans and provide a backdrop against which progress could be measured [39].

Reprinted with permission from McNaughton et al. [42]. Published by Dove Medical Press Ltd

Goal Attainment Scale (GAS) example.

Electronic versions of the GAS are being developed to facilitate shared decision making and progress assessment. As these efforts begin to extend across therapeutic indications and clinicians’ familiarity with this methodology increases, it is believed that the goal attainment approach will become more accessible, and thus used more frequently to help patients reach their goals successfully.

GAS-D and Patient-Centric Research

The goal attainment approach offers a number of advantages compared with traditional clinical or patient-reported measures because it permits assessment of patient-centric outcomes that may be neglected when traditional clinical or patient-reported scales are used [40].

Involving patients and their families in treatment decisions and the goal-setting process can motivate patients to become more involved in their treatment and may support the development of more realistic goals [41]. In addition, certain drawbacks observed with traditional outcome measures may be overcome. For instance, “floor” and “ceiling” effects may be avoided, because the goal attainment approach itself is designed to measure a range of expected treatment outcomes, limiting the chance for observed effects to fall outside the range of measurement [41]. Furthermore, the problem of reduced sensitivity to capturing clinically significant change may also be avoided, because items assessed are inherently important to the patient without being overshadowed by items included in the traditional outcome measures that may not reflect an individual patient’s presentation and/or are of lesser importance to the patient [41].

Successful implementation and validation of the GAS-D should allow for continued and increased use of this tool in both the clinical research and clinical practice settings, providing another measure for within- and between-group comparisons of patients with regard to treatment success. In addition, the GAS-D may offer a valuable framework by which clinicians and patients in real-world clinical practice can work together to establish meaningful treatment goals and quantify progress toward these goals [40].

The GAS-D has been implemented in a recently completed clinical study (NCT02972632) as a primary outcome measure intended to assess the progress of participants toward achieving their individual goals after a change in antidepressant medication for the treatment of MDD [40]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to use GAS-D as the primary outcome measure to assess achievement of patient-centric outcomes in MDD, and both primary and secondary GAS-D endpoints are being evaluated for consistency with outcomes assessed using more traditional measures.

Conclusions

Increased awareness of the need for patient-centric care and shared decision making may serve to drive the development of new, or adaptation of existing, tools to aid both patients and their clinicians in treatment evaluation that goes beyond the traditional focus on clinical symptom improvement. The goal attainment approach is a promising methodology that allows patients to work with their HCPs in setting individualized meaningful treatment goals. This approach allows for the assessment of patient-centric outcomes that may be neglected when more traditional assessment scales are used. The heterogeneous nature of MDD lends itself to the goal attainment approach, which ensures that goals set are relevant to each patient’s symptomatology and are reflective of overall improvement in MDD.

References

Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62.

Montgomery SA, Asberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–9.

European Commission. Personalised medicine. Background, conference reports, publications and links related to personalise medicine. https://ec.europa.eu/research/health/index.cfm?pg=policy&policyname=personalised. Accessed 14 May 2019.

Epstein R, Teagarden JR. Comparative effectiveness and personalized medicine: evolving together or apart? Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1783–7. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0642.

Institute of Medicine. Best care at lower cost: the path to continuously learning health care in America. Washington (DC): The National Academies Press; 2013. https://doi.org/10.17226/13444.

Légaré F, Witteman HO. Shared decision making: examining key elements and barriers to adoption into routine clinical practice. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:276–84. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1078.

World Health Organization. Sixty-ninth world health assembly: provisional agenda item 16.1; 15 April 2016. Framework on integrated, people-centred health services. https://www.who.int/servicedeliverysafety/areas/people-centred-care/framework/en/. Accessed 14 May 2019.

Levinson W, Lasser CS, Epstein RM. Developing physician communication skills for patient-centered care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1310–8. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0450.

US Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration, Center for Devices and Radiological Health; Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Patient preference information—voluntary submission, review in premarket approval applications, humanitarian device exemption applications, and de novo requests, and inclusion in decision summaries and device labeling: guidance for industry, Food and Drug Administration staff, and other stakeholders. 2016. https://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/deviceregulationandguidance/guidancedocuments/ucm081752.htm. Accessed 10 Sept 2018.

Hargraves I, LeBlanc A, Shah ND, Montori VM. Shared decision making: the need for patient-clinician conversation, not just information. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35:627–9. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1354.

Santana MJ, Manalili K, Jolley RJ, Zelinsky S, Quan H, Lu M. How to practice person-centred care: a conceptual framework. Health Expect. 2018;21:429–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12640.

Otte C, Gold SM, Penninx BW, et al. Major depressive disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16065. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2016.65.

World Health Organization. Depression: fact sheet. 2017. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/. Accessed 13 Nov 2017.

Trivedi MH. Major depressive disorder: remission of associated symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 6):27–32.

O’Leary OF, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. Faster, better, stronger: towards new antidepressant therapeutic strategies. Eur J Pharmacol. 2015;753:32–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2014.07.046.

Garcia-Toro M, Ibarra O, Gili M, et al. Adherence to lifestyle recommendations by patients with depression. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2012;5:236–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2012.04.003.

Cuijpers P, Li J, Hofmann SG, Andersson G. Self-reported versus clinician-rated symptoms of depression as outcome measures in psychotherapy research on depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:768–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.06.001.

Montoya A, Lebrec J, Keane KM, et al. Broader conceptualization of remission assessed by the remission from depression questionnaire and its association with symptomatic remission: a prospective, multicenter, observational study. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:352. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-1067-3.

Zimmerman M, Martinez JA, Attiullah N, et al. Why do some depressed outpatients who are in remission according to the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale not consider themselves to be in remission? J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(6):790–5. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.11m07203.

Kennedy S. Full remission: a return to normal functioning. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2002;27(4):233–4.

Zimmerman M, Martinez JH, Attiullah N, et al. A new type of scale for determining remission from depression: the Remission from Depression Questionnaire. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(1):78–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2012.09.006.

Battle CL, Uebelacker L, Friedman MA, Cardemil EV, Beevers CG, Miller IW. Treatment goals of depressed outpatients: a qualitative investigation of goals identified by participants in a depression treatment trial. J Psychiatr Pract. 2010;16(6):425–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000390763.57946.93.

Vares EA, Salum GA, Spanemberg L, Caldieraro MA, Fleck MP. Depression dimensions: integrating clinical signs and symptoms from the perspectives of clinicians and patients. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136037. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136037.

Gaasterland CM, Jansen-van der Weide MC, Weinreich SS, van der Lee JH. A systematic review to investigate the measurement properties of goal attainment scaling, towards use in drug trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2016;16:99. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0205-4.

Jones M, Kharawala S, Langham J, Gandhi P. Goal Attainment Scaling: a useful individualized clinical outcome measure. Value Health. 2014;17:A585 (abstract PRM239).

Kiresuk TJ, Sherman RE. Goal attainment scaling: a general method for evaluating comprehensive community mental health programs. Community Ment Health J. 1968;4(6):443–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01530764.

Ruble L, McGrew JH, Toland MD. Goal attainment scaling as an outcome measure in randomized controlled trials of psychosocial interventions in autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42:1974–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1446-7.

Rockwood K, Fay S, Song X, MacKnight C, Gorman M, Video-Imaging Synthesis of Treating Alzheimer’s Disease (VISTA) Investigators. Attainment of treatment goals by people with Alzheimer’s disease receiving galantamine: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2006;174:1099–105. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.051432.

Rockwood K, Graham JE, Fay S, ACADIE Investigators. Goal setting and attainment in Alzheimer’s disease patients treated with donepezil. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:500–7.

Rockwood K, Howlett S, Stadnyk K, Carver D, Powell C, Stolee P. Responsiveness of goal attainment scaling in a randomized controlled trial of comprehensive geriatric assessment. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:736–43.

Kiresuk TJ, Smith A, Cardillo JE. Goal attainment scaling: applications, theory and measurement. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1994.

Hellerstein DJ, Erickson G, Stewart JW, et al. Behavioral activation therapy for return to work in medication-responsive chronic depression with persistent psychosocial dysfunction. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;57:140–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2014.10.015.

Yang LH, Chen FP, Sia KJ, et al. “What matters most”: a cultural mechanism moderating structural vulnerability and moral experience of mental illness stigma. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:84–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.009.

McCusker J, Yaffe M, Sussman T, et al. Developing an evaluation framework for consumer-centred collaborative care of depression using input from stakeholders. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58(3):160–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371305800306.

Solberg LI, Crain AL, Rubenstein L, Unutzer J, Whitebird RR, Beck A. How much shared decision making occurs in usual primary care of depression? J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27(2):199–208. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2014.02.130164.

Pomerantz JI, Toney SD, Hill ZJ. Care coaching: an alternative approach to managing comorbid depression. Prof Case Manag. 2010;15:137–42. https://doi.org/10.1097/ncm.0b013e3181c00f0f (quiz 43-4).

Coote HM, MacLeod AK. A self-help, positive goal-focused intervention to increase well-being in people with depression. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2012;19:305–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1797.

DasMahapatra P, Raja P, Gilbert J, Wicks P. Clinical trials from the patient perspective: survey in an online patient community. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:166. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2090-x.

McNaughton E, Granskie J, Curran C, et al. Attitudes on goals in depression. AAFP annual meeting. Poster presented at: the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) Annual Congress; September 12–16, 2017; San Antonio, TX.

Parikh SV, Mucha L, Sarkey S, et al. A novel use of the goal attainment scale after change to vortioxetine in the treatment of major depressive disorder. Poster presented at American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology annual meeting; May 29-June 2, 2017; Miami, FL.

Turner-Stokes L. Goal attainment scaling (GAS) in rehabilitation: a practical guide. Clin Rehabil. 2009;23:362–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269215508101742.

McNaughton EC, Curran C, Granskie J, et al. Patient attitudes toward and goals for MDD treatment: a survey study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2019;13:959–67.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jennifer Schuster of Takeda Pharmaceuticals for her contributions to this manuscript.

Funding

Article processing charges were funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd., and Lundbeck LLC. All authors had full access to all of the references cited in this manuscript and take complete responsibility for the interpretation of any data presented here.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Editorial assistance in the preparation of this article was provided by Sharon J. Hirshey Dirksen, PhD, of inVentiv Medical Communications, LLC, a Syneos Health™ group company. Support for this assistance was funded by Takeda Pharmaceutical Company, Ltd. (Deerfield, IL, USA) and Lundbeck LLC (Deerfield, IL, USA).

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authorship Contributions

MM, SVP, SS, CF, AE, LM, and MO contributed to the conceptual design, and MM, AE, SS, MO, and SVP contributed to the methodological design. MM, LM, and MO completed the literature search, literature review, and data extraction. MM, SS, AE, CC, BWL, SVP, and MO participated in the analysis and interpretation of results. MM drafted the manuscript, and all authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosures

Maggie McCue is an employee of Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. Sara Sarkey is an employee of Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. Charlie Cao is an employee of Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. and Jennifer Schuster is an employee of Takeda Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc. Anna Eramo is an employee of Lundbeck LLC. Clément François was an employee of Lundbeck LLC. Lisa Mucha was an employee of Takeda Pharmaceuticals, USA, Inc. Sagar Parikh is a consultant to Takeda and Sunovion, has a research contract with Assurex Health, and owns shares in Mensante Corporation. Mark Opler is an employee of MedAvante-ProPhase. Briana Webber Lind is an employee of MedAvante-ProPhase.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9258965.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

McCue, M., Parikh, S.V., Mucha, L. et al. Adapting the Goal Attainment Approach for Major Depressive Disorder. Neurol Ther 8, 167–176 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-019-00151-w

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-019-00151-w