Abstract

Multiple sclerosis (MS) management presently aims to reach a state of no (or minimal) evidence of disease activity. The development and commercialization of new drugs has led to a renewed interest in family planning, since patients with MS may face a future with reduced (or no) disease-related neurological disability. The advice of neurologists is often sought by patients who want to have children and need to know more about disease control at conception and during pregnancy and the puerperium. When MS is well controlled, the simple withdrawal of drugs for patients who intend to conceive is not an option. On the other hand, not all treatments presently recommended for MS are considered safe during conception, pregnancy and/or breastfeeding. The objective of the present study was to summarize the practical and evidence-based recommendations for family planning when our patients (women and men) have MS.

Funding TEVA Pharmaceutical Brazil.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) treatment has evolved tremendously over the last two decades. Whereas a patient diagnosed with MS 30 years ago had very little hope of a future without severe neurological disability, most patients who receive the diagnosis now have access to a variety of pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments that can modify their disease evolution [1]. In the present scenario, MS management aims to reach a state of no (or minimal) evidence of disease activity in patients [2]. Therefore, while individuals with MS might not have considered parenthood in the past due to the potential disability, patients nowadays seem to have a different attitude towards having children. Family planning for patients with MS includes advice from neurologists regarding disease control at conception and during pregnancy and the puerperium. Since reactivation of well-controlled MS may lead to relapses and accumulated neurological disability, simple withdrawal of drugs for patients who intend to conceive is not an option. On the other hand, not all treatments presently recommended for MS are considered safe during conception, pregnancy and/or breastfeeding [3]. The objective of the present study was to summarize the practical and evidence-based recommendations for neurologists, obstetricians and urologists who discuss family planning with women and men with MS.

A panel of neurologists with experience in MS reviewed several aspects of the disease with regard to human reproduction. Their recommendations were established based on published evidence and the specialists’ expert opinion. The review of the literature was not limited by date and included specific words for each individual subject reviewed by the specialists. The authors used PubMed, Medline, SciELO, LILACS, the Cochrane Library and Google Scholar to identify relevant papers. Only papers with a title and abstract in English were reviewed; from the articles selected, the lists of references were further searched for potentially relevant citations. After 2 months of reviews, the panel met for a full day of discussions and elaboration of the material below. All recommendations presented here are evidence-based and were included with the approval of at least 80% of the authors.

This paper is a comprehensive review of medical literature on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors. All statements regarding the literature are cited in the references.

Level of Evidence

For obvious ethical reasons, there are no double-blind or placebo-controlled randomized studies on men or women with MS who intend to conceive, or on pregnant and/or breastfeeding women. The papers selected for this article typically come from anecdotal reports, case series, observational studies and national or international databases, using retrospective, prospective or cross-sectional cohorts of patients. Therefore, there is no evidence coming from Class I or II studies in this population of patients with MS, and all recommendations in the literature are, at best, Level C [4].

General Recommendations for Patients with MS Who Want to Have Children

Although both men and women with MS should have the disease under control before conceiving a child, this recommendation is particularly important for women. The risk of relapses in the post-natal period showed an independent correlation with the 12-month [5] and 24-month [6] annualized relapse rate preceding pregnancy. In addition, a higher number of postnatal relapses increased the risk of disability progression in women with MS [5]. Therefore, it is of essence that women with MS who intend to become pregnant have their disease under control for at least 1 year before conceiving. Should the patient have a new diagnosis of MS, the recommendation is to wait for at least 1 year in order to attempt to control disease activity before conceiving.

Antenatal Care for Women with MS

Pregnancy in a woman with MS does not constitute a case of “high-risk” pregnancy. Antenatal care follows the general recommendations, with the same scheme of dietary supplementation of folic acid, vitamins, minerals and iron that pregnant women need to have. Likewise, cessation of alcohol and tobacco use is important [7]. One aspect of antenatal care that may give rise to greater controversy is supplementation of vitamin D among pregnant women with MS. The plasma levels of vitamin D have not been found to be associated with the postnatal relapse rate in MS [8, 9], and general obstetric and neonatal outcomes seem to have little relationship to vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy [10]. Therefore, there is no particular reason to aim for high plasma levels of vitamin D in pregnant women with MS.

In summary, antenatal care for women with MS should follow the general recommendations of the gynecology and obstetrics societies of each country.

Vaccines

Obstetricians and gynecologists have very good opportunities to incorporate vaccination into the standard clinical care for women [11]. They specifically care for pregnant women who, along with their fetuses, can be particularly vulnerable to vaccine-preventable diseases and their related complications [12]. In patients with MS, vaccination can have peculiarities related to the disease itself and its treatment [13, 14].

Vaccination should be discussed with the patient before conception and should follow the recommendations and immunization calendar of each country. In general, if the woman has not been previously exposed or vaccinated against a certain disease, the risk/benefit of immunization during pregnancy should be assessed individually [15]. Inactivated vaccines, such as seasonal influenza and tetanus, can be used safely even during pregnancy. Vaccines with bacteria and those with attenuated viruses can be used before the woman conceives and may be used in the final trimester of pregnancy. These include Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) against tuberculosis, oral typhoid, measles-mumps-rubella (MMR), varicella/zoster and rotavirus [16]. Other vaccines that may be used during pregnancy on an exception basis include pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine and hepatitis B. The healthcare staff need to be aware that patients with MS should not receive live-virus vaccine (for example, yellow fever). These patients should be immunized only in some very specific situations, through case-by-case indication.

The Effect of Pregnancy on MS Relapses (Short-Term Outcomes)

Acute demyelinating relapses of MS can be worrisome during pregnancy and the puerperium. While pregnancy status typically reduces the number of clinical relapses, this number is not zero, and some patients may require treatment while pregnant. Reactivation of MS inflammatory activity is a characteristic feature of the postnatal period, and treatment of relapses may be necessary in the puerperium.

The mechanism underlying the changes in relapse rate during gestation and after delivery are ultimately a function of cytokine and hormone levels in the woman. Pregnancy is associated with downregulation of cell-mediated immunity, ultimately resulting in a shift towards a T-helper 2 (Th2) cytokine profile [17]. This shift leads to reduced levels of Th1 cytokines (interferon gamma and tumor necrosis factor alpha) and increased levels of Th2 cytokines (interleukins IL-4 and IL-10), which are essential for tolerance of the fetus during pregnancy [18]. In addition, the beneficial immunomodulatory effects of high levels of estrogen during pregnancy [19] may explain the overall reduction in MS activity during gestation.

Management of Relapses During Pregnancy

Fortunately, most women with MS will not develop neurological symptoms during or after pregnancy [20]. Relapses occurring during pregnancy, particularly in the first trimester, should be treated with corticosteroids only when they significantly affect the mother’s activities of daily living [21]. Although conflicting data have been published, corticosteroids used during pregnancy have been associated with orofacial cleft [22, 23]. There are no reports of other therapies (including immunoglobulin) for treatment of relapses during the gestational period in women diagnosed with MS.

Summarizing the recommendations regarding therapy for MS relapses during pregnancy, intravenous 3-day pulse of methylprednisolone (1 g/day) can be used if necessary. Prolonged oral administration of prednisone should be avoided, as well as the use of corticosteroids with placental effects, such as dexamethasone or betamethasone [24].

Management of Relapses After Delivery

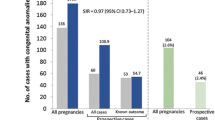

Studies from various countries show that relapses occur in 12–39% of women with MS during the puerperium [20, 25,26,27,28]. A low relapse rate preceding pregnancy [6, 21] and exposure to immunomodulatory drugs at the time of conception [6, 29] appear to be the only factors associated with lower numbers of postnatal relapses.

Following studies with conflicting results regarding the role of breastfeeding in preventing postnatal relapse [30, 31], a meta-analysis concluded that this protective effect, if present, is modest [32]. The recommendation is to encourage breastfeeding for its beneficial effect as a whole [33], with the important exception of (re)starting MS therapy with drugs that are detectable in breast milk. These drugs will be discussed later in this paper.

The use of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) has generated conflicting results in published papers. Although IVIG has a good safety profile, a recent meta-analysis demonstrated an ineffective cost–benefit profile from prescribing IVIG for prevention of relapses during the puerperium [34]. Different therapeutic schemes have been used; there are some uncontrolled studies and some studies controlled with 30-year-old historical patient data [34]. Briefly, using the present information on IVIG, approximately six women must be treated to avoid one relapse, which translates into a cost of over US$80,000 to prevent of a single postnatal MS relapse. Therefore, the evidence-based recommendation does not include IVIG in the management of postnatal reactivation of MS.

Monthly pulses of 1 g methylprednisolone have been proposed for prevention of relapse during the puerperium, but only two case series have been published [35, 36]. This approach has shown good results and is potentially safe, since the corticosteroid virtually disappears from breast milk within 4 h [36, 37]. Milk from this period could be discharged and the baby could be breastfed 4 h after the mother’s infusion. It is an inexpensive option that could be studied in detail and thus could become part of the recommendations for protection against puerperal relapses.

The Effect of Pregnancy on Disability (Long-Term MS Outcomes)

Pregnancy does not, in itself, negatively affect the course of MS [38]. While there are studies showing that parity was associated with better outcomes regarding disability progression in MS [39], others have not obtained the same results [40]. Irrespective of this divergence, the recommendation regarding pregnancy for women with MS remains a matter of reaching disease control before conception.

The Effect of MS on Obstetric, Neonatal and Delivery Outcomes

There are studies reporting higher rates of premature birth and lower birth weight among babies born to women with MS [38, 41, 42], while other studies did not show such results [43, 44]. All authors seem to agree that there is a higher rate of cesarean section among women with MS. This finding might be a reflection of fatigue, spasticity of lower limbs, slower progression of labor and/or pelvic organ dysfunction, which can all be features of MS [45]. The recommendation is that it is the obstetrician’s prerogative to indicate induced labor or a cesarean section.

There are no reported negative outcomes from the use of epidural, peridural, caudal, spinal, subarachnoid or intrathecal analgesia in MS [46]. Epidural analgesia can be safely used in women with MS who are giving birth [47]. Pregnancies in women with MS do not need to be classified as “high-risk” pregnancy. However, it is our recommendation that hospital-assisted delivery is a better option than “natural home birth”, “labor and delivery alone”, “water birth” and similar alternatives.

Symptomatic Drugs Often Used for Patients with MS

Patients with MS often present other conditions such as depression, fatigue, spasticity or gait abnormalities, which can all worsen during and after pregnancy. The drugs used to treat these conditions typically consist of small molecules taken orally. Except for antidepressants, data on the safety of these treatments are sparse.

Large-cohort studies [48,49,50,51] on the use of antidepressants by pregnant women and nursing mothers have indicated that these drugs are not particularly teratogenic. Conflicting data in the literature have suggested that antidepressants may have a small effect on fetal growth, while associations between paroxetine and cardiac defects, between citalopram and craniofacial malformations, and between venlafaxine and pulmonary hypertension in newborns have been described [51,52,53,54]. Women who use antidepressants late in pregnancy do not have lower production of breast milk, as was reported in the past [55].

The pharmacological profile of sertraline suggests that this drug might be an appropriate choice when antidepressant treatment is required during pregnancy. Sertraline has little interaction with other systems and presents linear pharmacokinetic characteristics, with a half-life of 24–26 h. Sertraline is also considered to be a good option for treating depression in nursing mothers [56].

Amantadine is often used to manage fatigue in MS, although its effect is disputable, and the recommendation of amantadine for this purpose is off-label [57, 58]. There are only anecdotal reports of exposure to amantadine during pregnancy, but due to teratogenicity in animal studies and occasional reports of severe malformation in humans, this drug should not be prescribed for pregnant women [59,60,61].

Modafinil is another drug used off-label for treatment of fatigue and cognitive dysfunction in MS [62, 63]. The effect of modafinil in MS, if any, is small and is poorly studied. There are no data in humans justifying its use during pregnancy, given that the effects on the mother and child are virtually unknown.

Fampridine is recommended for improving gait velocity for patients with MS. There is only one literature report regarding fampridine exposure during pregnancy, which showed good outcomes [64]. The recommendation is not to prescribe fampridine to women who intend to have children, or to pregnant or breastfeeding patients with MS.

Baclofen is a gamma-aminobutyric acid agonist used primarily as a muscle relaxant to improve spasticity. Although intrathecal baclofen seems to be a safe alternative during pregnancy in very specific cases [65], oral baclofen should not be prescribed at all [66]. There are no formal contraindications for breastfeeding while using baclofen, as the drug is detected only in small amounts in breast milk [65].

Men with MS Who Want to Have Children

While research on pregnancy among women with MS has increased considerably over recent decades, investigations in men with MS who father children still have a long way to go. Men with MS may present fertility impairment and sexual dysfunction, while semen itself may be affected by drugs.

Relative to control subjects, men with MS have been reported to have lower baseline levels of luteinizing hormone (LH), follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and testosterone [67]. Total sperm count, sperm motility and percentage of normal sperm morphology have been found to be lower in patients with MS than in controls [67]. These findings indicate that men with MS may exhibit a state of hypogonadotropic hypogonadism that can affect their fertility. It is interesting to observe that men with hypogonadism showed a higher risk of developing MS in large-population studies [68, 69], while low baseline levels of testosterone in men with MS were associated with worse disability outcomes [70]. Another large-population study showed that infertile men were at higher risk of developing not only MS, but also rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis and thyroiditis [71].

In addition to hormonal changes associated with MS, it is well known that 50–90% of men affected by MS can experience erectile dysfunction, ejaculatory dysfunction, orgasmic dysfunction and/or reduced libido [72, 73]. Higher rates of depression and fatigue have been described in patients with MS and sexual dysfunction [74, 75].

There are few studies on the potential effect of MS therapy on men who have fathered children. The use of interferon beta and glatiramer acetate by the father has not been associated with worse neonatal outcomes [76,77,78]. There is still a lack of data on other therapeutic options for MS.

Assisted Reproductive Technology

Assisted reproductive technology (ART) is used to treat infertility, in relation to both the woman’s ovule and the man’s sperm. While ART does not seem to influence the risk of MS relapses in men [79], women can have higher MS activity when undergoing the same procedure [80]. At least in theory, the use of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonists should be a better option for women with MS undergoing ART [80]. GnRH antagonists have the same clinical outcomes as GnRH agonists, without leading to a decrease in estrogen [81]. The potential protective effect of estrogen and estradiol in MS has been known for a few years [82].

The Effect of MS Therapy on Childbearing

The majority of studies on pregnancy and MS have reported on relapse rates among the mothers and on the effect of disease-modifying drugs (DMDs) on newborns. A recent comprehensive review by Vaughn et al. [83] summarized the data regarding the potential risks of the use of DMDs during pregnancy and their prescribing recommendations. All the published data come from observational reports and may not be considered very robust [84]. On the other hand, the overly simplistic solution of withdrawing all treatments from women who intend to conceive (or are already pregnant) does not take into consideration the potential severity of MS [85]. Severe rebounding of MS activity may occur when fingolimod or natalizumab is withdrawn during pregnancy (or at the time of pregnancy planning) [86,87,88,89,90,91]. In the modern era, when decision-making relating to MS does not allow for anything less than optimal disease control [92], it is unacceptable that young women are simply told to stop therapy without being informed of the consequences of this action. Furthermore, as previously discussed, low relapse rates in the postpartum period are associated with good disease control at conception [6]. The present knowledge on DMDs can serve as guidance for specific recommendations for men and women with MS who want to have children. For easier understanding of this complex subject, DMDs are classified and presented here as “self-injectable drugs”, “oral drugs” or “monoclonal antibodies”. A summary of the data on each drug is shown in Table 1. More detailed information is presented below.

It is extremely important to understand that the data presented in this paper are not necessarily true for biosimilar drugs (interferon beta and monoclonal antibodies), follow-on glatiramer acetate and generic oral drugs. The information reported in the present review comes from the original patented drugs.

Self-Injectable DMDs

The “older” category of immunomodulatory drugs used for treating MS comprises interferon beta and glatiramer acetate. Long-term data and the large number of cases of maternal exposure to these drugs have provided reassuring results regarding their safety during pregnancy. There are no specific recommendations for discontinuation of these treatments within the context of family planning.

Interferon Beta

Different formulations of interferon beta have been used for treating MS, and outcomes relating to exposure during pregnancy have been reported from all of them. Two of the formulations consist of the naturally occurring amino acid sequence of interferon beta and are known as interferon beta-1a, with the commercial names Avonex® (intramuscular administration) and Rebif® (subcutaneous administration). The third formulation is known as interferon beta-1b (Betaseron®) and consists of a modified amino acid sequence, presenting a cysteine-to-serine mutation at amino acid 17, along with a deletion of the amino terminal methionine [93].

Interferon beta targets immune cells, which gives rise to reduced antigen presentation and T-cell proliferation and induces altered cytokine and matrix metalloproteinase expression that culminates in suppression of inflammation [94]. The interferon beta molecule is over 20 kDa in size and is not believed to cross the placenta [95]. Pegylation of interferon beta results in a prolonged half-life of the active substance, with an extended dosage interval, thus enabling fewer injections and improving adherence to treatment [96]. Pegylation stabilizes the molecule by protecting it from degradation and proteolysis [97], thereby leading to better bioavailability, with a potential beneficial impact on efficacy [98]. This new formulation is also available for treating MS under the commercial name Plegridy®.

In total, over 3000 reports of the use of interferon beta during any stage of pregnancy can be found in the literature, and the outcomes are not considered deleterious. Earlier reports on exposure to interferon beta during pregnancy pointed towards a higher risk of spontaneous abortion and low birth weight [99, 100], but later data seem reassuring. More recent papers with higher numbers of patients have suggested that the percentages of live births, spontaneous abortions and malformations resulting from exposure to interferon beta are similar to those observed in the general population [101,102,103,104,105]. Although some later studies do correlate interferon beta exposure with lower birth weight, the newborns in those studies were still over 3200 g on average [106]. The World Health Organization defines “low birth weight” as “weight at birth of less than 2500 g” [107]. Therefore, the widespread notion that interferon beta can lead to low birth weight in newborns is not correct. Higher incidence of cesarean deliveries and pre-term (37 weeks) birth have also been correlated with exposure to interferon beta in some reports [45].

The European Medicines Agency and the US Food and Drug Administration label interferon beta as a drug that should be avoided during pregnancy unless the benefits of its use outweigh the risks. The recommendation is to maintain use of the drug irrespective of the patient`s wish to conceive. Once the diagnosis of pregnancy has been established, the use of interferon beta throughout gestation will be a decision made jointly by the physician in charge and the patient, taking into consideration the risk/benefit profile of this therapeutic option.

The proportion of interferon beta that is transferred to breast milk is very low, and the estimate breastfed infant dose is 0.006% of the maternal dose [108]. In addition, when given orally, interferon beta has shown no systemic biological effect [109]. Therefore, women who intend to breastfeed may use interferon beta without concerns that this might affect the child.

Few cases have been reported among men undergoing treatment with interferon beta who father children, and there is no compelling evidence of obstetric or neonatal risks [77, 78].

Glatiramer Acetate

Glatiramer acetate consists of acetate salts of synthetic polypeptides, containing four naturally occurring amino acids: l-glutamic acid, l-alanine, l-tyrosine and l-lysine. This complex molecule has an average length of 45–100 amino acids, with a molecular weight of 5–9 kDa. A substantial percentage of the therapeutic dose of glatiramer acetate is hydrolyzed at the site of the injection and interacts locally with peripheral blood lymphocytes [110]. This drug has been used worldwide for two decades and has shown no teratogenic or mutagenic effects [111]. In late 2016, the European Medicines Agency updated the label for Copaxone®, such that it is no longer considered contraindicated during pregnancy. According to the Food and Drug Administration, Copaxone® is a “Category B” drug, meaning that no risks have been shown in animal fetuses, but there are no well-controlled studies related to human pregnancy. Reports on over 5000 cases of branded Copaxone® exposure during pregnancy reinforce the lack of teratogenic effects [112, 113]. These findings provide important knowledge for better counseling for women with MS who intend to become pregnant and should not forgo the use of DMDs while attempting to conceive. Continuous use of glatiramer acetate throughout pregnancy can also be discussed with patients who may require this particular approach [114].

Breastfeeding while using glatiramer acetate is potentially safe. This drug is rapidly degraded after subcutaneous injection and cannot be detected in the plasma, urine or feces [115].

There are only two specific reports on men undergoing treatment with glatiramer acetate who fathered children [77, 78]. No association between paternal exposure to glatiramer acetate at the time of conception and a risk of adverse outcomes was shown.

Oral Drugs

While the “older” self-injectable DMDs discussed above are large molecules that generally do not cross the placenta or have any presence in breast milk, the “newer” oral drugs are small molecules that behave differently. Fingolimod freely crosses the blood–brain barrier [116] and the placental barrier [117]. Teriflunomide can cross the placental barrier [117] and should not be used by men or women with MS who intend to conceive. It is likely that dimethyl fumarate can cross the placenta as well [117], while it is still uncertain whether cladribine can reach the fetus [118]. It is generally better to avoid the use of small molecules that can potentially reach the fetus among women who want to have children. The amount of data in pregnancy exposure registries on the use of these oral drugs for treating MS remains insufficient. As safety data accumulates through pharmacovigilance programs, the recommendation for avoiding oral drugs during pregnancy may change.

The washout period for these oral drugs varies; for fingolimod it has been established as 2–3 months. In order to decrease the period between DMD withdrawal and conception, discontinuation of oral MS therapy should be planned such that it is only implemented 2 or 3 months after withdrawal of oral contraceptives. Pregnancy after stopping the use of birth control pills may be achieved after only one cycle in approximately 20% of women, and may take up to 1 year for 80% [119].

Fingolimod

Fingolimod was the first oral drug to be approved for MS therapy [120, 121]. It is a sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor modulator that is administered orally once daily, and its use leads to a reduction in the number of circulating lymphocytes by preventing their egress from secondary lymph organs [120]. This oral therapy has been shown to be effective at a dose of 0.5 mg/day in double-blind, placebo-controlled studies and in trials comparing it with interferon beta-1a. Studies continue to assess the long-term efficacy and safety of newer DMDs, including fingolimod, as Faissner and Gold reinforce in a comprehensive 2018 review [121].

Animal data on exposure to fingolimod during gestation suggests that birth malformation can occur, possibly due to the influence of sphingosine-1-phosphate on embryogenetic vascular formation [122]. Data in relation to human pregnancy are scarce, but fetal abnormalities have been reported at higher rates than what would be expected for the general population [123]. The present recommendation is to discontinue fingolimod for at least 2 months prior to conception [123, 124]. As fingolimod can be identified in human breast milk, this treatment should not be resumed if the mother intends to breastfeed [125].

Regarding fingolimod withdrawal in the context of pregnancy planning, the neurologist needs to be aware of the risks of disease rebound following fingolimod discontinuation [86, 91, 126]. There are no predictive factors defining the rebound risk group, and patients should be closely monitored after stopping fingolimod [126].

Dimethyl Fumarate

Dimethyl fumarate derives from free fumaric acid, a substance that has poor gastrointestinal absorption [127]. The ester derivatives of fumaric acid have better absorption but may still lead to gastrointestinal symptoms that affect tolerance to the drug [127]. Although relatively new for treating MS, fumarates have been used to treat psoriasis since the mid-1990s [128].

Dimethyl fumarate targets antioxidant mechanisms and exerts anti-inflammatory effects through stimulation of regulatory T lymphocytes [129]. The drug can modify a variety of proteins involved in T-cell activation through its electrophilic activity [130]. Dimethyl fumarate can reduce the production of nitric oxide synthase and decrease the levels of proinflammatory cytokines, including those that depend on mediation by nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) [131]. It is likely that the drug can induce a wider spectrum of immunological changes in patients with MS, but the studies performed so far suggest that the main mechanism of action involves elimination of proinflammatory activated T cells [129].

The data on fetal exposure to dimethyl fumarate are very limited, but no increased risk of fetal abnormalities or adverse pregnancy outcomes have been observed thus far [83, 132]. It is not known whether dimethyl fumarate or its metabolites are present in human milk.

There are no reports in the literature suggesting acute reactivation of MS following discontinuation of dimethyl fumarate. Likewise, the drug is known to have a short half-life, and there is no evidence of its accumulation [133]. Therefore, pregnancy planning following withdrawal from dimethyl fumarate should not pose the same concerns observed with other drugs, as discussed above.

Teriflunomide

Teriflunomide is the active metabolite of leflunomide, a drug that has been successfully used for treating rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis for many years [134], and has been approved for treating MS. It induces reversible inhibition of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase, a critical enzyme in the synthesis of pyrimidine. Lymphocytes require pyrimidine for proliferation, and thus teriflunomide limits the number of circulating peripheral lymphocytes. In addition, this drug affects the antigen presentation of dendritic cells and stimulates the Th1–Th2 shift in the lymphocyte profile [134].

Teriflunomide was originally labeled as a substance with high teratogenic effects. The drug label states that it should be avoided at all costs among men and women with MS who intend to have children [135]. Animal studies on maternal exposure to pyrimidine inhibitors have shown that the drug can induce neural tube defects, cleft palate, tail deformities, limb malformations, abnormalities in vertebrae (cervical to sacral), membranous ventricular septum defect and persistent truncus arteriosus [136]. The abnormalities observed in animal fetuses have been dose-dependent, and very high doses rendered the fetus unviable. Malformations were a function of dihydroorotate dehydrogenase inhibition, and early exposure gave rise to the possibility of multiple congenital abnormalities [137]. Since teriflunomide can be detected at low levels in human semen, it is recommended that men undergoing therapy with this drug avoid reproduction [138].

Despite all the concerns regarding teratogenicity, no adverse outcomes relating to human pregnancy have been seen with leflunomide [139, 140] or teriflunomide [138]. The number of pregnancies studied remains small, but the initial findings have been reassuring to mothers and fathers who might be overwhelmed with worries after reading the drug label.

Elimination of teriflunomide is slow, and the drug may still be detected in human blood 2 years after discontinuation [141]. Accelerated elimination of teriflunomide with activated charcoal, cholestyramine or colestipol hydrochloride is recommended when the drug needs to be eliminated rapidly [141, 142]. Particularly in relation to pregnancy planning, the recommendation for accelerated elimination of the drug is important, but this also needs to be implemented as soon as a pregnancy is diagnosed in women with MS who are using teriflunomide.

Accelerated elimination can be achieved through the following schemes: (1) cholestyramine 8 g three times daily for 11 days; or (2) activated charcoal 50 g twice daily for 11 days; or (3) colestipol (colesevelam hydrochloride), four 625-mg tablets in the morning plus three 625-mg tablets in the evening [141]. It would be of great help to physicians if the company commercializing teriflunomide for treatment of MS could guarantee provision of the full dose of an accelerated elimination drug whenever necessary.

Teriflunomide is contraindicated during breastfeeding [138].

Cladribine

Cladribine is a chlorinated deoxyadenosine prodrug that is activated by intracellular phosphorylation to become an active purine nucleoside analogue [143]. Oral cladribine may have beneficial immunological effects in the treatment of MS through the targeting of specific lymphocyte populations [144, 145]. In addition, cladribine appears to reduce the availability of vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) and E-selectin, all of which are important for lymphocyte transit through the blood–brain barrier [146]. Despite initial concerns regarding adverse events during the use of cladribine (lymphocytopenia, herpes zoster infections and malignancies), this drug has been approved for treating MS in several countries now.

The recommended dose of cladribine in MS is 3.5 mg/kg body weight over 2 years, or 1.75 mg/kg per year. Each course of treatment consists of two treatment weeks: one at the beginning of the first month and one at the beginning of the second month of the respective treatment years (4 or 5 days of 10 mg or 20 mg as a single daily dose, depending on body weight). Although this therapeutic scheme is very convenient, the long-term systemic effects of the drug may raise concerns regarding pregnancy over this 2-year period. Data on pregnancy and cladribine are scarce, and despite the lack of reported adverse outcomes, this drug should be avoided among patients who intend to conceive [147]. Men and women using cladribine should not conceive for at least 6 months after the last dose. Recent research strongly suggests that cladribine can exert its effects mainly via B-cell depletion [148]. Therefore, with caution and attention to all potential differences there may exist among drugs, data on pregnancy in patients with MS using other drugs with similar mechanisms of action might ultimately help building a “B-cell depletion” safety database.

Cladribine is contraindicated for women who breastfeed [147].

Monoclonal Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies are increasingly being used for disease management. However, experience with and data on the potential reproductive and developmental toxicities relating to these agents remain sparse [149]. Monoclonal antibodies cannot be transported across the placenta by means of simple diffusion, since they are hydrophilic molecules with a molecular mass exceeding 100 kDa. They require active transportation across the placental barrier via a specific receptor-mediated mechanism [150], which may not take place until after several weeks of placental development [151]. Therefore, it would be expected that early maternal exposure to monoclonal antibodies does not negatively affect fetal organogenesis [152]. This consideration is important, since women with MS undergoing therapy with monoclonal antibodies tend to be patients with more aggressive neurological disease. Discontinuation of their therapy might lead to severe disease reactivation, and therefore, planning for conception and pregnancy among these patients is an extra challenge for the physician in charge.

Natalizumab

Natalizumab was the first monoclonal antibody developed for treating MS and is still one of the most potent therapies for disease control. Natalizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody that binds to integrins of both α4β1 (very late antigen 4, VLA-4) and α4β7 (lymphocyte Peyer’s patch adhesion molecule 1, LPAM-1) [153]. This unique mechanism of action blocks leukocyte attachment to cerebral endothelial cells, thus reducing inflammation at the blood–brain barrier and inside the central nervous system [154]. The main impediments to more widespread use of this drug relate to potential development of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) in patients with MS undergoing therapy with natalizumab [155]. The recommended dose of natalizumab is 300 mg administered by means of infusion every 4–8 weeks [156].

Over 350 cases of maternal exposure to natalizumab have been reported with complete outcomes [157]. This database shows that although the overall rate of birth defects was higher than that expected for a healthy population (5.05%), there were no specific patterns of malformations that would suggest a drug effect [157]. The babies’ weights were within expected values, and no differences in the spontaneous abortion rate or gestational age at delivery were observed relative to the general population [157].

In Germany and Italy, case series of early exposure to natalizumab during pregnancy have been reported [158,159,160,161]. The obstetric and neonatal outcomes have been unremarkable in these cases of early exposure (up to 12 weeks of pregnancy). On the other hand, the use of natalizumab in the third trimester of pregnancy has been systematically correlated with hematological abnormalities in babies [162, 163]. In two newborns, long-term in utero exposure to natalizumab resulted in a reduced T-lymphocyte chemotaxis rate, which may have compromised their early-life host defense [164]. Reactivation of MS (observed clinically and/or via MRI) was reported in 95.5% of patients with MS who discontinued natalizumab due to pregnancy [165]. The same study showed worsening of disease disability in 27.3% of these patients. Disease reactivation is one of the most difficult aspects of discontinuing natalizumab in any patient, and during pregnancy it poses an additional challenge [166]. There are reports of severe MS reactivation after withdrawal of natalizumab in relation to pregnancy planning [89] and after pregnancy was diagnosed [87, 88, 90]. At least in theory, natalizumab might be administered until the 30th week of pregnancy in cases of very aggressive disease, but this recommendation is based upon very few cases in the literature [157, 159].

In order to avoid serious complications over the course of the treatment with natalizumab, family planning needs to be discussed with the patient before treatment initiation.

Breastfeeding is not recommended during natalizumab use, since the drug can be identified in breast milk [153, 167, 168]. Although the levels of natalizumab in breast milk are minute, breastfeeding safety cannot be determined at this time [168].

Alemtuzumab

In 1983, a group of researchers in Cambridge, UK, developed an IgM rat antibody that depleted lymphocytes, thus improving the chances of success in organ transplantation [169]. This antibody evolved to an IgG2b CAMPATH-1 Mab compound, called Cambridge Pathology 1 (CAMPATH-1), and it proved to be a very potent immunosuppressive drug targeting only white blood cells [169]. CAMPATH-1 was later studied for a possible role in purging of lymphocytes prior to autologous transplantation to treat acute lymphocytic leukemia [170]. Subsequently, it became clear that the antibody of this potent drug targeted CD52 [171]. Nomenclature standards for biological therapies led to changing the name of the drug to alemtuzumab. Alemtuzumab not only results in dramatic depletion of the T-cell population, but also seems to affect the complex reconstitution of lymphocytes in the immune repertoire [172]. Although alemtuzumab has only recently been incorporated into the therapeutic options for treating MS, a group in Cambridge has used it to treat MS since the early 1990s [173]. The drug was approved by the European Medicines Agency and the Food and Drug Administration in 2014 as therapy for MS with cytolytic properties against CD52 of lymphocytes. It is used in infusions of 12 mg/day for five consecutive days in the first year, and for three consecutive days 12 months later.

The number of pregnancies with alemtuzumab exposure is relatively small and has not yet reached 200 cases [174]. The data on these pregnancies have typically been presented at congresses and conferences, and no definitive recommendations can be made at this time. No adverse outcomes have been associated with the use of alemtuzumab.

Alemtuzumab has a short half-life, ranging from 2 to 32 h after the first administration and 1–14 days after the last dose in patients with leukemia, who use higher doses than those used for MS cases [175]. As with other monoclonal antibodies, alemtuzumab will not cross the placental barrier in the first weeks of embryogenesis. Therefore, at least in theory, conception occurring while alemtuzumab is being used should raise no particular concerns regarding disease in the fetus, and no particular recommendations for washout should be necessary. However, the autoimmune disorders that the mother may develop during therapy with alemtuzumab may pose a problem [176]. For example, autoimmune thyroid disease, which affects 30–40% of patients undergoing therapy with alemtuzumab [177], may translate into hypothyroidism during pregnancy.

Breastfeeding is contraindicated during the use of alemtuzumab, but infusions can be organized in such a way as to overcome this problem.

Ocrelizumab

Until recently, T cells were considered to be the main players in inflammation leading to demyelination and degeneration in MS. Trials with rituximab, which provides B-cell depletion, yielded conflicting results, and DMD development continued to target T lymphocytes [178]. Although trials with rituximab did not yield very favorable results in MS cases [178], some groups have had good experience with this drug in treating their own patients [179].

Ocrelizumab was developed for the purpose of targeting B lymphocytes in MS and is the most recently approved drug for MS therapy. It is a humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody that depletes B cells through antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity [180]. It is used in infusions at doses of 300 mg (first infusion) and 300 mg (second infusion) 2 weeks later. Thereafter, the dose is 600 mg every 6 months.

The data on exposure to ocrelizumab during pregnancy amounts to only 13 cases with clear exposure to the drug during the embryogenetic period [181]. For rituximab, there have been approximately 200 cases of exposure to autoimmune diseases in general [182]. Clear exposure within 6 months of the infusion has been reported in 102 cases, seven of which were patients with MS [183]. Therefore, there are no data to define the safety of maternal exposure. The half-life of rituximab is 21 days [184], and it is 26 days for ocrelizumab [185]. Again, at least in theory, conception occurring during the use of B-cell-depleting therapy should not raise any particular concerns regarding disease in the fetus and thus should avoid concerns regarding washout periods. When used throughout pregnancy, rituximab has been associated with B-cell depletion in the baby [183, 186] and lymphoid tissue abnormalities in exposed animals [187]. Babies with this hematological finding showed spontaneous recovery of B-cell levels after 6 months and had no complications.

Breastfeeding is contraindicated during the use of ocrelizumab, but scheduling postnatal infusions can overcome this problem.

Conclusion

The present study summarizes recommendations for physicians who discuss family planning with women and men with MS. The authors believe that reproductive issues in MS will remain an important issue for researchers and clinicians. Results from real-world databases and pharmacovigilance will add to the knowledge on this subject and will continue to change family planning for people with MS. A disease that once was a reason not to have children is now a potentially controllable disease. Medications with unknown effects on fetuses are now extensively studied regarding maternal and paternal exposure at conception. Fetal exposure to drugs used for MS treatment do not constitute a reason for abortion due to fear of the unknown.

References

Doshi A, Chataway J. Multiple sclerosis, a treatable disease. Clin Med (Lond). 2017;17:530–6. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.17-6-530.

Giovannoni G, Tomic D, Bright JR, et al. “No evident disease activity”: the use of combined assessments in the management of patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017;23:1179–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517703193.

Vukusic S, Marignier R. Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy in the ‘treatment era’. Nat Rev Neurol. 2015;11:280–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2015.53.

Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M, et al. Developing clinical guidelines. West J Med. 1999;170:348–51.

Portaccio E, Ghezzi A, Hakiki B, et al. Postpartum relapses increase the risk of disability progression in multiple sclerosis: the role of disease modifying drugs. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014;85:845–50. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2013-306054.

Hughes SE, Spelman T, Gray OM, et al. Predictors and dynamics of postpartum relapses in women with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2014;20:739–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458513507816.

Amato MP, Bertolotto A, Brunelli R, et al. Management of pregnancy-related issues in multiple sclerosis patients: the need for an interdisciplinary approach. Neurol Sci. 2017;38:1849–58. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-017-3081-8.

Langer-Gould A, Huang S, Van Den Eeden SK, et al. Vitamin D, pregnancy, breastfeeding and postpartum multiple sclerosis relapses. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:310–3. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2010.291.

Runia TF, Neuteboom RF, de Groot CJ, et al. The influence of vitamin D on postpartum relapse and quality of life in pregnant multiple sclerosis patients. Eur J Neurol. 2015;22:479–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12594.

Roth DE, Leung M, Mesfin E, et al. Vitamin D supplementation during pregnancy: state of the evidence from a systematic review of randomised trials. BMJ. 2017;359:j5237. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j5237.

Leader S, Perales PJ. Provision of primary-preventive health care services by obstetrician-gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:391–5.

Swamy GK, Heine RP. Vaccinations for pregnant women. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:212–26. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000581.

Frederiksen JL, Topsøe Mailand M. Vaccines and multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2017;136:49–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.12837.

Pellegrino P, Carnovale C, Perrone V, et al. Efficacy of vaccination against influenza in patients with multiple sclerosis: the role of concomitant therapies. Vaccine. 2014;32:4730–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.06.068.

Keller-Stanislawski B, Englund JA, Kang G, et al. Safety of immunization during pregnancy: a review of the evidence of selected inactivated and live attenuated vaccines. Vaccine. 2014;32:7057–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.09.052.

Wiley K, Regan A, McIntyre P. Immunization and pregnancy—who, what, when and why? Aust Prescr. 2017;40:122–4. https://doi.org/10.18773/austprescr.2017.046.

Al-Shammri S, Rawoot P, Azizieh F, et al. Th1/Th2 cytokine patterns and clinical profiles during and after pregnancy in women with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2004;222:21–7.

Kidd P. Th1/Th2 balance: the hypothesis, its limitations, and implications for health and disease. Altern Med Rev. 2003;8:223–46.

Gold SM, Voskuhl RR. Estrogen treatment in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2009;286:99–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2009.05.028.

Alroughani R, Alowayesh MS, Ahmed SF, et al. Relapse occurrence in women with multiple sclerosis during pregnancy in the new treatment era. Neurology. 2018;90:e840–6. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000005065.

Miller DH, Fazekas F, Montalban X, et al. Pregnancy, sex and hormonal factors in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2014;20:527–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458513519840.

Smets I, Van Deun L, Bohyn C, et al. Corticosteroids in the management of acute multiple sclerosis exacerbations. Acta Neurol Belg. 2017;117:623–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13760-017-0772-0.

Xiao WL, Liu XY, Liu YS, et al. The relationship between maternal corticosteroid use and orofacial clefts—a meta-analysis. Reprod Toxicol. 2017;69:99–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2017.02.006.

Vackova Z, Vagnerova K, Libra A, et al. Dexamethasone and betamethasone administration during pregnancy affects expression and function of 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 in the rat placenta. Reprod Toxicol. 2009;28:46–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2009.02.006.

Hellwig K, Beste C, Schimrigk S, et al. Immunomodulation and postpartum relapses in patients with multiple sclerosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2009;2:7–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1756285608100416.

Finkelsztejn A, Fragoso YD, Ferreira ML, et al. The Brazilian database on pregnancy in multiple sclerosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2011;113:277–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2010.11.016.

Fares J, Nassar AH, Gebeily S, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in Lebanese women with multiple sclerosis (the LeMS study): a prospective multicentre study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e011210. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011210.

Jesus-Ribeiro J, Correia I, Martins AI, et al. Pregnancy in multiple sclerosis: a Portuguese cohort study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;17:63–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2017.07.002.

Fragoso YD, Boggild M, Macias-Islas MA, et al. The effects of long-term exposure to disease-modifying drugs during pregnancy in multiple sclerosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2013;115:154–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.04.024.

Langer-Gould A, Huang SM, Gupta R, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding and the risk of postpartum relapses in women with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:958–63. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2009.132.

Portaccio E, Ghezzi A, Hakiki B, et al. Breastfeeding is not related to postpartum relapses in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2011;77:145–50. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e318224afc9.

Pakpoor J, Disanto G, Lacey MV, et al. Breastfeeding and multiple sclerosis relapses: a meta-analysis. J Neurol. 2012;259:2246–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-012-6553-z.

Holla-Bhar R, Iellamo A, Gupta A, Smith JP, Dadhich JP. Investing in breastfeeding—the world breastfeeding costing initiative. Int Breastfeed J. 2015;10:18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-015-0032-y.

Rosa GR, O’Brien AT, Nogueira EA, et al. There is no benefit in the use of postnatal intravenous immunoglobulin for the prevention of relapses of multiple sclerosis. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2018;76:361–6. https://doi.org/10.1590/0004-282x20180041.

de Seze J, Chapelotte M, Delalande S, et al. Intravenous corticosteroids in the postpartum period for reduction of acute exacerbations in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2004;10:596–7.

Boz C, Terzi M, Zengin Karahan S, et al. Safety of IV pulse methylprednisolone therapy during breastfeeding in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517717806.

Cooper SD, Felkins K, Baker TE, et al. Transfer of methylprednisolone into breast milk in a mother with multiple sclerosis. J Hum Lact. 2015;31:237–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334415570970.

Hellwig K. Pregnancy in multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol. 2014;72:39–42. https://doi.org/10.1159/000367640.

Masera S, Cavalla P, Prosperini L, et al. Parity is associated with a longer time to reach irreversible disability milestones in women with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2015;21:1291–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458514561907.

McCombe PA, Callaway LK. Multiparity in women with multiple sclerosis causes less long-term disability: no. Mult Scler. 2014;20:1435–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458514541979.

Dahl J, Myhr KM, Daltveit AK, et al. Pregnancy, delivery, and birth outcome in women with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;65:1961–3.

Chen YH, Lin HL, Lin HC. Does multiple sclerosis increase risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes? A population-based study. Mult Scler. 2009;15:606–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458508101937.

Mueller BA, Zhang J, Critchlow CW. Birth outcomes and need for hospitalization after delivery among women with multiple sclerosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:446–52.

Ferrero S, Pretta S, Ragni N. Multiple sclerosis: management issues during pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;115:3–9.

Lu E, Wang BW, Guimond C, et al. Disease-modifying drugs for multiple sclerosis in pregnancy: a systematic review. Neurology. 2012;79:1130–5. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182698c64.

Bornemann-Cimenti H, Sivro N, Toft F, et al. Neuraxial anesthesia in patients with multiple sclerosis—a systematic review. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2017;67:404–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjan.2016.09.015.

Pastò L, Portaccio E, Ghezzi A, et al. Epidural analgesia and cesarean delivery in multiple sclerosis post-partum relapses: the Italian cohort study. BMC Neurol. 2012;12:165. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-12-165.

Furu K, Kieler H, Haglund B, et al. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and venlafaxine in early pregnancy and risk of birth defects: population based cohort study and sibling design. BMJ. 2015;17(350):h1798. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h1798.

Huybrechts KF, Palmsten K, Mogun H, et al. National trends in antidepressant medication treatment among publicly insured pregnant women. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2013;35(3):265–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2012.12.010.

Yonkers KA, Forray A, Smith MV. Maternal antidepressant use and pregnancy outcomes. JAMA. 2017;318(7):665–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.9182.

Berard A, Zhao JP, Sheehy O. Antidepressant use during pregnancy and the risk of major congenital malformations in a cohort of depressed pregnant women: an updated analysis of the Quebec Pregnancy Cohort. BMJ Open. 2017;7(1):e013372. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013372.

Ross LE, Grigoriadis S, Mamisashvili L, et al. Selected pregnancy and delivery outcomes after exposure to antidepressant medication: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(4):436–43. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.684.

Huybrechts KF, Bateman BT, Palmsten K, et al. Antidepressant use late in pregnancy and risk of persistent pulmonary hypertension of the newborn. JAMA. 2015;313(21):2142–51. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.5605.

Udechuku A, Nguyen T, Hill R, et al. Antidepressants in pregnancy: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(11):978–96. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048674.2010.507543.

Grzeskowiak LE, Leggett C, Costi L, et al. Impact of serotonin reuptake inhibitor use on breast milk supply in mothers of preterm infants: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84(6):1373–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/bcp.13575.

Orsolini L, Bellantuono C. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors and breastfeeding: a systematic review. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2015;30:4–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.2451.

Generali JA, Cada DJ. Amantadine: multiple sclerosis-related fatigue. Hosp Pharm. 2014;49:710–2. https://doi.org/10.1310/hpj4908-710.

Pucci E, Branãs P, D’Amico R, et al. Amantadine for fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD002818. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD002818.

Kranick SM, Mowry EM, Colcher A, et al. Movement disorders and pregnancy: a review of the literature. Mov Disord. 2010;25:665–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/mds.23071.

Seier M, Hiller A. Parkinson’s disease and pregnancy: an updated review. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2017;40:11–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.05.007.

Pandit PB, Chitayat D, Jefferies AL, et al. Tibial hemimelia and tetralogy of Fallot associated with first trimester exposure to amantadine. Reprod Toxicol. 1994;8:89–92.

Shangyan H, Kuiqing L, Yumin X, et al. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of modafinil versus placebo in the treatment of multiple sclerosis fatigue. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;19:85–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2017.10.011.

Ford-Johnson L, DeLuca J, Zhang J, et al. Cognitive effects of modafinil in patients with multiple sclerosis: a clinical trial. Rehabil Psychol. 2016;61:82–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039919.

Maillart E, Gout O, Lubetzki C, et al. Favorable outcome of a pregnancy after fampridine exposition during the first month. J Neurol Sci. 2016;370:158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jns.2016.09.033.

Tandon SS, Hoskins I, Azhar S. Intrathecal baclofen pump—a viable therapeutic option in pregnancy. Obstet Med. 2010;3:119–20. https://doi.org/10.1258/om.2010.100016.

Baclofen and pregnancy: birth defects and withdrawal symptoms. Prescrire Int. 2015;24:214.

Safarinejad MR. Evaluation of endocrine profile, hypothalamic–pituitary–testis axis and semen quality in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:1368–75.

Pakpoor J, Goldacre R, Schmierer K, et al. Testicular hypofunction and multiple sclerosis risk: a record-linkage study. Ann Neurol. 2014;76:625–8.

Glazer CH, Tottenborg SS, Giwereman A, et al. Male fator infertility and risk of multiple sclerosis: a register-based cohort study. Mult Scler. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517734069.

Bove R, Musallam A, Healy BC, et al. Low testosterone is associated with disability in men with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2014;20:1584–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458514527864.

Brubaker WD, Li S, Baker LC, et al. Increased risk of autoimmune disorders in infertile men: analysis of US claims data. Andrology. 2018;6:94–8.

Prévinaire JG, Lecourt G, Soler JM, et al. Sexual disorders in men with multiple sclerosis: evaluation and management. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2014;57:329–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2014.05.002.

Fode M, Krogh-Jespersen S, Brackett NI, et al. Male sexual dysfunction and infertility associated with neurological disorders. Asian J Androl. 2012;14:61–8.

Marck CH, Jelinek PL, Weiland TJ, et al. Sexual function in multiple sclerosis and associations with demographic, disease and lifestyle characteristics: an international cross-sectional study. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:210.

Balsamo R, Arcaniolo D, Stizzo M, et al. Increased risk of erectile dysfunction in men with multiple sclerosis: an Italian cross-sectional study. Cent Eur J Urol. 2017;70:289–95. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/9820245.

Hellwig K, Haghikia A, Gold R. Parenthood and immunomodulation in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2010;257:580–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-009-5376-z.

Pecori C, Giannini M, Portaccio E, et al. Paternal therapy with disease modifying drugs in multiple sclerosis and pregnancy outcomes: a prospective observational multicentric study. BMC Neurol. 2014;14:114. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2377-14-114.

Lu E, Zhu F, Zhao Y, et al. Birth outcomes in newborns fathered by men with multiple sclerosis exposed to disease-modifying drugs. CNS Drugs. 2014;28:475–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-014-0154-6.

Trofimenko V, Hotaling JM. Fertility treatment in spinal cord injury and other neurologic disease. Transl Androl Urol. 2016;5:102–16. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2223-4683.2015.12.10.

Hellwig K, Correale J. Artificial reproductive techniques in multiple sclerosis. Clin Immunol. 2013;149:219–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2013.02.001.

Al-Inany HG, Youssef MA, Ayeleke RO, et al. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone antagonists for assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;4:CD001750. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd001750.pub4.

Niino M, Hirotani M, Fukazawa T, et al. Estrogens as potential therapeutic agents in multiple sclerosis. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem. 2009;9:87–94.

Vaughn C, Bushra A, Kolb C, et al. An update on the use of disease-modifying therapy in pregnant patients with multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2018;32:161–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-018-0496-6.

Krueger WS, Anthony MS, Saltus CW, et al. Evaluating the safety of medication exposures during pregnancy: a case study of study designs and data sources in multiple sclerosis. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2017;4:139–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40801-017-0114-9.

Fragoso YD. Is it correct for a woman with multiple sclerosis to forgo medication because she may become pregnant? Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2013;71:826–7. https://doi.org/10.1590/0004-282X20130134.

Meinl I, Havla J, Hohlfeld R, et al. Recurrence of disease activity during pregnancy after cessation of fingolimod in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517731913.

Novi G, Ghezzi A, Pizzorno M, et al. Dramatic rebounds of MS during pregnancy following fingolimod withdrawal. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017;4:e377. https://doi.org/10.1212/NXI.0000000000000377.

De Giglio L, Gasperini C, Tortorella C, et al. Natalizumab discontinuation and disease restart in pregnancy: a case series. Acta Neurol Scand. 2015;131:336–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.12364.

Martinelli V, Colombo B, Dalla Costa G, et al. Recurrent disease-activity rebound in a patient with multiple sclerosis after natalizumab discontinuations for pregnancy planning. Mult Scler. 2016;22:1506–8.

Verhaeghe A, Deryck OM, Vanopdenbosch LJ. Pseudotumoral rebound of multiple sclerosis in a pregnant patient after stopping natalizumab. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2014;3:279–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msard.2013.10.001.

Sempere AP, Berenguer-Ruiz L, Feliu-Rey E. Rebound of disease activity during pregnancy after withdrawal of fingolimod. Eur J Neurol. 2013;20:e109–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12195.

Saposnik G, Montalban X. Therapeutic inertia in the new landscape of multiple sclerosis care. Front Neurol. 2018;9:174. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.00174.

Markowitz C. Development of interferon-beta as a therapy for multiple sclerosis. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2004;9:363–74.

Markowitz CE. Interferon-beta: mechanism of action and dosing issues. Neurology. 2007;68:S8–11.

Waysbort A, Giroux M, Mansat V, et al. Experimental study of transplacental passage of alpha interferon by two assay techniques. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1993;37:1232–7.

Madsen C. The innovative development in interferon beta treatments of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Brain Behav. 2017;7:e00696. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.696.

Kang JS, Deluca PP, Lee KC. Emerging PEGylated drugs. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2009;14:363–80. https://doi.org/10.1517/14728210902907847.

Hu X, Olivier K, Polack E, et al. In vivo pharmacology and toxicology evaluation of polyethylene glycol-conjugated interferon beta-1a. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338:984–96. https://doi.org/10.1124/jpet.111.180661.

Sandberg-Wollheim M, Frank D, Goodwin TM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes during treatment with interferon beta-1a in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2005;65:802–6.

Boskovic R, Wide R, Wolpin J, et al. The reproductive effects of beta interferon therapy in pregnancy: a longitudinal cohort. Neurology. 2005;65:807–11.

Patti F, Cavallaro T, Lo Fermo S, et al. Is in utero early-exposure to interferon beta a risk factor for pregnancy outcomes in multiple sclerosis? J Neurol. 2008;255:1250–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-008-0909-4.

Sandberg-Wollheim M, Alteri E, Moraga MS, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in multiple sclerosis following subcutaneous interferon beta-1a therapy. Mult Scler. 2011;17:423–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458510394610.

Amato MP, Portaccio E, Ghezzi A, et al. Pregnancy and fetal outcomes after interferon-β exposure in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2010;75:1794–802. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181fd62bb.

Coyle PK, Sinclair SM, Scheuerle AE, et al. Final results from the Betaseron (interferon β-1b) Pregnancy Registry: a prospective observational study of birth defects and pregnancy-related adverse events. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004536. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004536.

Thiel S, Langer-Gould A, Rockhoff M, et al. Interferon-beta exposure during first trimester is safe in women with multiple sclerosis—a prospective cohort study from the German Multiple Sclerosis and Pregnancy Registry. Mult Scler. 2016;22:801–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458516634872.

Weber-Schoendorfer C, Schaefer C. Multiple sclerosis, immunomodulators, and pregnancy outcome: a prospective observational study. Mult Scler. 2009;15:1037–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458509106543.

Organization WH. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems, tenth revision. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

Hale TW, Siddiqui AA, Baker TE. Transfer of interferon β-1a into human breastmilk. Breastfeed Med. 2012;7:123–5. https://doi.org/10.1089/bfm.2011.0044.

Polman C, Barkhof F, Kappos L, et al. Oral interferon beta-1a in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a double-blind randomized study. Mult Scler. 2003;9:342–8.

Messina S, Patti F. The pharmacokinetics of glatiramer acetate for multiple sclerosis treatment. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2013;9:1349–59. https://doi.org/10.1517/17425255.2013.811489.

Comi G, Moiola L. Glatiramer acetate. Neurologia. 2002;17:244–58.

Fragoso YD. Glatiramer acetate to treat multiple sclerosis during pregnancy and lactation: a safety evaluation. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13:1743–8. https://doi.org/10.1517/14740338.2014.955849.

Sandberg-Wollheim M, Neudorfer O, Grinspan A, et al. Pregnancy outcomes from the branded glatiramer acetate pregnancy database. Int J MS Care. 2018;20:9–14. https://doi.org/10.7224/1537-2073.2016-079.

Miller AE. Multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapy and pregnancy. Mult Scler. 2016;22:715–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458516642316.

Ziemssen T, Neuhaus O, Hohlfeld R. Risk-benefit assessment of glatiramer acetate in multiple sclerosis. Drug Saf. 2001;24:979–90.

Chun J, Hartung HP. Mechanism of action of oral fingolimod (FTY720) in multiple sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33:91–101. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNF.0b013e3181cbf825.

Buraga I, Popovici RE. Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy: current considerations. Sci World J. 2014;2014:513160. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/513160.

Orlowski RZ. Successful pregnancy after cladribine therapy for hairy cell leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:187–8.

Cronin M, Schellschmidt I, Dinger J. Rate of pregnancy after using drospirenone and other progestin-containing oral contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:616–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b46f54.

Brown BA, Kantesaria PP, McDevitt LM. Fingolimod: a novel immunosuppressant for multiple sclerosis. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41(10):1660–8.

Faissner S, Gold R. Efficacy and safety of the newer multiple sclerosis drugs approved since 2010. CNS Drugs. 2018;32:269–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-018-0488-6.

Lu E, Wang BW, Alwan S, et al. A review of safety-related pregnancy data surrounding the oral disease-modifying drugs for multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2014;28:89–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-013-0131-5.

Karlsson G, Francis G, Koren G, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in the clinical development program of fingolimod in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2014;82:674–80. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000000137.

Jones B. Multiple sclerosis: study reinforces need for contraception in women taking fingolimod. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:125. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrneurol.2014.22.

Alroughani R, Altintas A, Al Jumah M, et al. MS pregnancy and the use of disease-modifying therapies in patients with multiple sclerosis: benefits versus risks. Mult Scler Int. 2016;2016:1034912. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/1034912.

Yoshii F, Moriya Y, Ohnuki T, et al. Neurological safety of fingolimod: an updated review. Clin Exp Neuroimmunol. 2017;8:233–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/cen3.12397.

Linker RA, Haghikia A. Dimethyl fumarate in multiple sclerosis: latest developments, evidence and place in therapy. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2016;7:198–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/2040622316653307.

Altmeyer PJ, Matthes U, Pawlak F, et al. Antipsoriatic effect of fumaric acid derivatives. Results of a multicenter double-blind study in 100 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;30:977–81.

Mills EA, Ogrodnik MA, Plave A, Mao-Draayer Y. Emerging understanding of the mechanism of action for dimethyl fumarate in the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Front Neurol. 2018;23:5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.00005.

Blewett MM, Xie J, Zaro BW, et al. Chemical proteomic map of dimethyl fumarate-sensitive cysteines in primary human T cells. Sci Signal. 2016;9:rs10. https://doi.org/10.1126/scisignal.aaf7694.

Gillard GO, Collette B, Anderson J, et al. DMF, but not other fumarates, inhibits NF-kappaB activity in vitro in an Nrf2-independent manner. J Neuroimmunol. 2015;283:74–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.04.006.

Gold R, Phillips JT, Havrdova E, et al. Delayed-release dimethyl fumarate and pregnancy: preclinical studies and pregnancy outcomes from clinical trials and postmarketing experience. Neurol Ther. 2015;4:93–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-015-0033-1.

Sheikh SI, Nestorov I, Russell H, et al. Tolerability and pharmacokinetics of delayed-release dimethyl fumarate administered with and without aspirin in healthy volunteers. Clin Ther. 2013;35(1582–1594):e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2013.08.009.

Fragoso YD, Brooks JB. Leflunomide and teriflunomide: altering the metabolism of pyrimidines for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2015;8:315–20. https://doi.org/10.1586/17512433.2015.119343.

Cree BA. Update on reproductive safety of current and emerging disease-modifying therapies for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2013;19:835–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458512471880.

Fukushima R, Kanamori S, Hirashiba M, et al. Teratogenicity study of the dihydroorotate-dehydrogenase inhibitor and protein tyrosine kinase inhibitor leflunomide in mice. Reprod Toxicol. 2007;24:310–6.

Fukushima R, Kanamori S, Hirashiba M, et al. Critical periods for the teratogenicity of immune-suppressant leflunomide in mice. Congenit Anom (Kyoto). 2009;49:20–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-4520.2008.00217.x.

Kieseier BC, Benamor M. Pregnancy outcomes following maternal and paternal exposure to teriflunomide during treatment for relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. Neurol Ther. 2014;3(2):133–8.

Bérard A, Zhao JP, Shui I, et al. Leflunomide use during pregnancy and the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018;77:500–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-212078.

Weber-Schoendorfer C, Beck E, Tissen-Diabaté T, et al. Leflunomide—a human teratogen? A still not answered question. An evaluation of the German Embryotox pharmacovigilance database. Reprod Toxicol. 2017;71:101–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.reprotox.2017.04.007.

Robertson D, Dixon C, Aungst A, et al. Tolerability and efficacy of colestipol hydrochloride for accelerated elimination of teriflunomide. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2017;10:1403–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512433.2017.1395280.

Freedman MS. Teriflunomide in relapsing multiple sclerosis: therapeutic utility. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2013;4:192–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/2040622313492810.

Leist TP, Weissert R. Cladribine: mode of action and implications for treatment of multiple sclerosis. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2011;34:28–35. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNF.0b013e318204cd90.

Leist TP, Vermersch P. The potential role for cladribine in the treatment of multiple sclerosis: clinical experience and development of an oral tablet formulation. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23:2667–76. https://doi.org/10.1185/030079907X233142.

Savic RM, Novakovic AM, Ekblom M, et al. Population pharmacokinetics of cladribine in patients with multiple sclerosis. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2017;56:1245–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40262-017-0516-6.

Mitosek-Szewczyk K, Stelmasiak Z, Bartosik-Psujek H, et al. Impact of cladribine on soluble adhesion molecules in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand. 2010;122:409–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0404.2010.01330.x.

Hartung H, Aktas O, Kieseier B, et al. Development of oral cladribine for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2010;257:163–70.

Baker D, Herrod SS, Alvarez-Gonzalez C, et al. Both cladribine and alemtuzumab may effect MS via B-cell depletion. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017;4:e360. https://doi.org/10.1212/NXI.0000000000000360.

Azim HA Jr, Azim H, Peccatori FA. Treatment of cancer during pregnancy with monoclonal antibodies: a real challenge. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2010;6:821–6. https://doi.org/10.1586/eci.10.77.

Saji F, Samejima Y, Kamiura S, et al. Dynamics of immunoglobulins at the feto-maternal interface. Rev Reprod. 1999;4:81–9.

Pentsuk N, van der Laan JW. An interspecies comparison of placental antibody transfer: new insights into developmental toxicity testing of monoclonal antibodies. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol. 2009;86:328–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdrb.20201.

DeSesso JM, Williams AL, Ahuja A, et al. The placenta, transfer of immunoglobulins, and safety assessment of biopharmaceuticals in pregnancy. Crit Rev Toxicol. 2012;42:185–210. https://doi.org/10.3109/10408444.2011.653487.

Hao L, Fang-Hong S, Shi-Ying H, et al. A review on clinical pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, and pharmacogenomics of natalizumab: a humanized anti-alpha4 integrin monoclonal antibody. Curr Drug Metab. 2018. https://doi.org/10.2174/1389200219666180427165841 (E-pub).

Rudick RA, Sandrock A. Natalizumab: alpha 4-integrin antagonist selective adhesion molecule inhibitors for MS. Expert Rev Neurother. 2004;4:571–80.

Johnson KP. Natalizumab (Tysabri) treatment for relapsing multiple sclerosis. Neurologist. 2007;13:182–7.

Zhovtis Ryerson L, Frohman TC, Foley J, et al. Extended interval dosing of natalizumab in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87:885–9. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp-2015-312940.

Friend S, Richman S, Bloomgren G, et al. Evaluation of pregnancy outcomes from the Tysabri® (natalizumab) pregnancy exposure registry: a global, observational, follow-up study. BMC Neurol. 2016;16:150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-016-0674-4.

Hellwig K, Haghikia A, Gold R. Pregnancy and natalizumab: results of an observational study in 35 accidental pregnancies during natalizumab treatment. Mult Scler J. 2011;17:958–63.

Ebrahimi N, Hebstritt S, Gold R, et al. Pregnancy and fetal outcomes following natalizumab exposure in pregnancy. A prospective, controlled observational study. Mult Scler J. 2015;21:198–205.

Portaccio E, Annovazzi P, Ghezzi A, et al. Pregnancy decision-making in women with multiple sclerosis treated with natalizumab. I: fetal risks. Neurology. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000005067.

Portaccio E, Annovazzi P, Ghezzi A, et al. Pregnancy decision-making in women with multiple sclerosis treated with natalizumab. II: maternal risks. Neurology. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000005068.

Haghikia A, Langer-Gould A, Rellensmann G, et al. Natalizumab use during the third trimester of pregnancy. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:891–5.

Guilloton L, Pegat A, Defrance J, et al. Neonatal pancytopenia in a child, born after maternal exposure to natalizumab throughout pregnancy. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod. 2017;46:301–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogoh.2017.02.008.

Schneider H, Weber CE, Hellwig K, et al. Natalizumab treatment during pregnancy—effects on the neonatal immune system. Acta Neurol Scand. 2013;127:e1–4. https://doi.org/10.1111/ane.12004.

Kleerekooper I, Leurs CE, Dekker I, et al. Disease activity following pregnancy-related discontinuation of natalizumab in MS. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2018;5:e424. https://doi.org/10.1212/NXI.0000000000000424.

Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Miravalle A, Schowinsky J, et al. Update on PML and PML-IRIS occurring in multiple sclerosis patients treated with natalizumab. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2012;71:604–17. https://doi.org/10.1097/NEN.0b013e31825caf2c.

Proschmann U, Thomas K, Thiel S, et al. Natalizumab during pregnancy and lactation. Mult Scler J. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1177/1352458517728813.

Baker TE, Cooper SD, Kessler L, et al. Transfer of natalizumab into breast milk in a mother with multiple sclerosis. J Hum Lact. 2015;31:233–6.

Hale G, Bright S, Chumbley G, et al. Removal of T cells from bone marrow for transplantation: a monoclonal antilymphocyte antibody that fixes human complement. Blood. 1983;62:873–82.

Hale G, Swirsky D, Waldmann H, et al. Reactivity of rat monoclonal antibody CAMPATH-1 with human leukaemia cells and its possible application for autologous bone marrow transplantation. Br J Haematol. 1985;60:41–8.