Abstract

The present study focuses on the Rayleigh equation derived in the case of a Hall thruster plasma having dust contamination, produced near the exit of the channel due to the finite divergence of the accelerated ions and the sputtering of the walls. In the presence of negatively charged dust particles, a modified form of the well-known Rayleigh equation of fluid dynamics is realized. The modified equation takes the form of the Rayleigh equation for a particular band of oscillation frequency, revealing that the Rayleigh instability shall occur in the thruster only for the oscillations having frequencies within this band. For better understanding, the variation of frequency band with various parameters, viz. dust density, dust charge number, dust mass, electron temperature and ion density, has been traced out.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hall thrusters are coaxial plasma accelerators regarded as one of the most streamlined and combative electric propulsion devices having numerous spacecraft applications in telecommunications satellites and other commercial space missions [1]. In general, these consist of three parts, namely discharge region (anode), cathode and magnetic field. The insulated discharge region is cylindrical chamber called channel, in which ionization and acceleration of the propellant are performed in the presence of crossed axial electric field and radial magnetic field. Cathode is located externally around the channel, and gas is fed through the base into the channel and dispersed eventually. Electrons trying to reach the anode experience a transverse magnetic field, which decreases their mobility and traps them; hence, the electrons trace out spiral motion along the axis of the thruster in the E × B direction, constituting the Hall current. Trapped electrons in the channel undergo collisions with the propellant atoms, creating ions. Ions so produced experience the electric field produced between the channel (positive) and the ring of electrons (negative) and accelerate out of the thruster as a strong ion beam. These ions impart force to the electron cloud due to which thrust is generated, which is transferred to the magnetic field and hence to the magnetic circuit of the thruster [2,3,4]. Bombardment of the electrons and the ions erodes the walls of the channel, which leads to the addition of dust to the chamber that is likely to affect the efficiency and lifetime of the Hall thrusters [5, 6]. Further, the major flaw of Hall thrusters is large exhaust-beam divergence, which may cause electrostatic charging and thus the communication interference of satellites [7]. Hence, for the efficient and hassle-free thrusters operations, a number of parameters are to be checked and fixed, for example, lower beam divergence, minimum erosion rate and optimum thrust-to-power ratio. Above all, the major challenge is to handle or suppress the oscillations produced in the chamber, which gives rise to different types of instabilities.

Choueiri [8] has discussed different types of discharge instabilities in Hall thrusters ranging from 103 to 109 Hz domain. Theoretical model of ion beam instability which arises due to the influence of boundaries with fixed electrical potentials on an ion flux in Hall thrusters was developed by Kapulkin et al. [9]. Lafleur et al. [10] have investigated characteristics and transport effects of the electron drift instability in Hall-effect thrusters. Lazurenko et al. [11] have explored anomalous electron transport phenomena and high-frequency instability in a Hall thruster. Chable and Rogier [12] have carried out numerical investigation for low-frequency oscillations in the SPT with regard to Buneman’s instabilities. Further, gradient-driven Rayleigh-type instabilities, by neglecting the thermal motions of the plasma species in Hall thrusters, have been analytically studied by Litvak and Fisch [13]. In the Hall thrusters, due to the drift velocities difference between the ions and the electrons, an electric field is also produced in the azimuthal direction, which generates the electrostatic waves in the same direction; these waves can gain free energy from the density gradient, grow up and become unstable in the plasma. Hence, one can think of the performance of the Hall thrusters in a better manner by having in-depth understanding of physical phenomena responsible for these instabilities. Therefore, the study of instabilities has always been the prime focus of concerned fraternity from time to time with the development of this device [14,15,16,17,18,19].

In the present article, we focus on the Rayleigh instability occurring due to the gradients in densities, velocities and the fields. In view of the erosion of the walls of the channel due to ion sputtering, we also include the dust particles, which are generally negatively charged [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Special focus is on the derivation of Rayleigh equation in the Hall thruster plasma and the frequency band condition of the oscillations of Rayleigh instability in the presence of dust contamination.

Derivation of modified Rayleigh equation

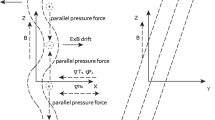

In the proposed model, Hall thruster plasma channel consists of ions, electrons and dust particles. The plasma is subjected to an axial electric field \(\vec{E}\) (along x-axis) and radial magnetic field \(\vec{B}\) (along z-axis). The strength of magnetic field is chosen in such a manner that the electrons get magnetized and the ions and dust particles remain unmagnetized in the channel. The electrons will experience \(\vec{E}\) × \(\vec{B}\) drift in the azimuthal direction (y-axis), whereas the ions and the dust particles are restricted axially (x-axis) by electric field \(\vec{E}\). Parameters defining all the three species completely are mass, velocity, density and temperature, symbolically represented as (\(M_{\text{i}}\), \(\vec{\upsilon }_{\text{i}}\), \(n_{\text{i}}\), \(T_{\text{i}}\)), (\(M_{\text{e}}\), \(\vec{\upsilon }_{\text{e}}\), \(n_{\text{e}}\), \(T_{\text{e}}\)) and (\(M_{\text{d}}\), \(\vec{\upsilon }_{\text{d}}\), \(n_{\text{d}}\), \(T_{\text{d}}\)) with subscripts \(i\), \(e\) and \(d\) for the ions, the electrons and the dust particles, respectively.

The thermal motion of the ions has been neglected (\(T_{\text{i}} = 0\)), and thus, the pressure gradient term in the equation of motion of the ion fluid is ignored. The unperturbed densities and velocities of the species are represented as (\(n_{\text{i0}}\), \(n_{\text{e0}}\), \(n_{\text{d0}}\)) and (\(\upsilon_{\text{i0}}\), \(\upsilon_{\text{e0}}\), \(\upsilon_{\text{d0}}\)) where their perturbed parts are taken as (\(n_{\text{i1}}\), \(n_{\text{e1}}\), \(n_{\text{d1}}\)) and (\(\vec{\upsilon }_{\text{i1}}\), \(\vec{\upsilon }_{\text{e1}}\), \(\vec{\upsilon }_{\text{d1}}\)). The perturbed value of the electric field is taken as \(\vec{E}_{1}\) (associated potential \(\phi_{1}\)). The fundamental equations are as follows:

This is to be noted that the collisions between the electrons and neutrals have been neglected in view of the fact that the Rayleigh instability arises due to the density gradient in the channel. The oscillations of the perturbed quantities are represented as ~ \(e^{{i(\omega t - k_{y} y)}}\), where \(\omega\) is the frequency of oscillations and \(k_{y}\) is the propagation constant. With the help of linearized equations of motion, x and y components of the ion velocities, electron velocities and dust velocities are obtained as:

Here, \(\varOmega = \frac{eB}{{M_{\text{e}} }}\) is the electron cyclotron frequency and \(\hat{\omega } = \omega - k_{y} \upsilon_{\text{e0}} .\)

Together with Eqs. (7) to (12), we solve the linearized continuity equation for the ions, electrons and dust particles for obtaining the perturbed ion, electron and dust density, respectively. We further make use of the following linearized form of the Poisson’s equation:

By using the perturbed densities of the ions, the electrons and the dust particles in the above Poisson’s equation and using the symbol \(\phi_{1} ''\) for \(\frac{{\partial^{2} \phi_{1} }}{{\partial x^{2} }}\), we obtain the following:

Now we notice that the quantity \(e\sqrt {\frac{{n_{\text{i0}} }}{{M_{\text{i}} \varepsilon_{0} }}}\) is the ion plasma frequency, say \(\omega_{\text{i}}\), \(e\sqrt {\frac{{n_{\text{e0}} }}{{M_{\text{e}} \varepsilon_{0} }}}\) is the electron plasma frequency, say \(\omega_{\text{e}}\), and \(eZ_{\text{d}} \sqrt {\frac{{n_{\text{d0}} }}{{M_{\text{d}} \varepsilon_{0} }}}\) is the dust plasma frequency, say \(\omega_{\text{d}}\). With these symbols and some other mathematical simplifications, Eq. (14) reads

Conditions for Rayleigh instability: Frequency band

In the present work, we assume the ion and the electron densities to be maximum in the middle of the acceleration channel, i.e., \(\eta_{j0} = \eta_{j00} \exp \left[ { - 18\left( {x/d} \right)^{2} } \right]\), where \(\eta_{j00}\) is the peak value of \(n_{\text{i0}}\) and \(n_{\text{e0}}\). The dust density is considered to be maximum toward the exit of the chamber, given by \(n_{\text{d0}} = n_{\text{d00}} \exp \left[ { - 18\left\{ {(x - 0.025)/d} \right\}^{2} } \right]\), where \(n_{\text{d00}}\) is the maximum dust density. The drift velocity distribution of the electron is taken as step-like profile \(\upsilon_{\text{e0}} = \upsilon_{\text{e00}} \left[ {1 + \exp \left( {3 - 55(x/d)} \right)} \right]^{{ - \frac{1}{8}}} .\)

Now we examine the perturbed part of Eq. (15), which takes the following form:

This can be seen that Eq. (16) is a modified form of the Rayleigh equation frequently used in the fluid dynamics, as the original form of the Rayleigh equation there reads \(\frac{{\partial^{2} \phi }}{{\partial x^{2} }} - k^{2} \phi + \frac{k\phi }{\omega - kV}\left( {\frac{{\partial^{2} V}}{{\partial x^{2} }}} \right) = 0\). Equation (16) can achieve this form under certain conditions. This also follows that the oscillations will grow into the Rayleigh instability only when their frequency falls within a frequency band governed by the following inequality:

Equation (17) gives a range of frequencies lying in the band. It is apparent from this frequency band that the higher cutoff frequency attains larger values for the higher temperature of the electrons and the dust particles. Therefore, a wider frequency band is observed in a more practical situation. This frequency band is of utmost importance and has not been explored earlier [32,33,34] in the dusty Hall thruster plasma, and hence, this is a novel result.

Results and discussion

In order to analyze the frequency band of the oscillations in the channel, the upper and lower cutoff frequencies \(\omega_{\text{cutoff}}\) have been plotted graphically based on Eq. (17) with the parameters commonly used in the Hall thrusters [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42]. The electron density profile, density gradient profile, electron velocity profile and the second derivative of the velocity profile are shown in Figs. 1, 2. The upper and lower frequencies with axial distance (channel length), dust density, electron density and magnetic field have been shown graphically in Figs. 3, 4, 5 and 6.

Variation of cutoff frequency \(\omega_{\text{cutoff}}\) with the axial distance \(x\) in the plasma having Xe ions (M = 131 amu), when \(B = 0.010\) T, \(Z_{\text{d}}\) = 800, \(T_{\text{e}} = 20\) eV, \(T_{\text{d}} = 0.01\) eV, \(n_{\text{i0}} = 10^{18}\) /m3, \(n_{\text{d0}} = 5 \times 10^{13}\) /m3, \(n_{e0} = n_{i0} - Z_{d} n_{d0}\), \(\upsilon_{e0} = 10^{5}\) m/s, \(\upsilon_{\text{i0}} = 10^{4}\) m/s, \(m_{\text{d}}\) = \(10^{ - 25}\) kg, \(k_{y} = 400\) /m, \(Y_{\text{e}} =\)\(Y_{\text{i}} = Y_{\text{d}} =\)\(2\) and \(d = 7.0\) cm

Variation of cutoff frequency \(\omega_{\text{cutoff}}\) with the dust density \(n_{\text{d0}}\) for different masses of dust particles in the plasma having Xe ions, when the other parameters are the same as in Fig. 3

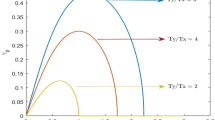

Variation of cutoff frequency \(\omega_{\text{cutoff}}\) with the electron density \(n_{\text{e0}}\) for different dust charge number and electron temperature in the plasma having Xe ions, when the other parameters are the same as in Fig. 3

Variation of cutoff frequency \(\omega_{\text{cutoff}}\) with the magnetic field \(B\) for different density of ions in the plasma having Xe ions, when the other parameters are the same as in Fig. 3

Figure 3 shows the variation of the upper and the lower cutoff frequencies in the channel of Hall thruster, which indicates that there is negligible difference between the lower and upper cutoff frequencies toward the anode, which means the frequency band carries negligible width this side. However, after the middle (\(x\) = 0) of the chamber, the frequency band is found to increase toward the exit. This implies that oscillations with comparatively higher frequency or smaller wavelength will be unstable toward the exit plane of the channel.

Figure 4 shows the effect of dust particles’ density on the \(\omega_{\text{cutoff}}\) for their different masses. The upper cutoff frequency is found to be of higher magnitude in the case of higher dust density, but the lower frequency remains constant since it is independent of density of the dust particles (please see the lines marked as upper frequency (\(m_{\text{d}}\) = \(10^{ - 25}\) kg) and lower frequency (common) (\(m_{\text{d}}\) = \(10^{ - 25}\) kg)). In the case of heavy dust particles, the upper cutoff frequency is found to be smaller; as a result, the frequency band is reduced. It means the oscillations with comparatively higher frequency or smaller wavelength will be unstable in the presence of lighter dust particles in the thruster. However, if the mass of the dust particles is higher, the oscillations of relatively lower frequency would also be unstable.

Figure 5 shows the impact of the electron density on \(\omega_{\text{cutoff}}\) for different dust charge number \(Z_{\text{d}}\) and electron temperature Te. The upper cutoff frequency attains lower values in the case of larger electron density, but it acquires higher values for the larger electron temperature [39] as well as with the larger dust charge. This follows that thermal motion of the electrons and the dust charge raise the frequency band of the instability. It means that the oscillations with comparatively higher frequency or smaller wavelength will be unstable in the presence of higher electron temperature and larger dust charge number.

Figure 6 shows the impact of the magnetic field on \(\omega_{\text{cutoff}}\) for different ion density in the plasma. The upper cutoff frequency increases with the increasing magnetic field and the decreasing ion density [39], but lower frequency decreases slightly with the magnetic field. This implies that the stronger magnetic field raises the oscillation frequency band of the said instability, and the oscillations with broad range frequencies would be prone to the instability. On the other hand, a comparison of the upper lines marked as upper frequency (\(n_{\text{i0}}\) = 1 × 1018/m3 and \(n_{\text{i0}}\) = 1.5 × 1018/m3) reveals that the frequency band for the Rayleigh instability is reduced for the larger number of the ions in the acceleration channel.

Conclusions

The frequency band of oscillations for the Rayleigh instability was explored analytically, and the variation of lower and upper frequencies of the oscillations with various parameters was graphically analyzed. It was found that the higher-frequency oscillations are more unstable for the higher values of the dust density and the dust charge number, larger thermal motion of the electrons, lower ion density and the stronger magnetic field. However, the lower-frequency oscillations are found to be more unstable when the heavy dust particles are created in the Hall thruster plasma or the density of the electrons is increased.

References

Boeuf, J.P.: Tutorial: physics and modeling of Hall thrusters. J. Appl. Phys. 121, 011101 (2017)

Goebel, D.M., Katz, I.: Fundamentals of Electric Propulsion: Ion and Hall Thrusters. Jet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology (2008)

Staack, D., Staack, Y., Fisch, N.J.: Temperature gradient in Hall thrusters. Appl. Phys. Lett. 84, 3028 (2004)

Frisbee, R.H.: Advanced space propulsion for the 21st century. J. Propul. Power 19, 1129 (2003)

Goebel, D.M., Katz, I.: Fundamentals of Electric Propulsion: Ion and Hall Thrusters, pp. 385–392. Wiley, Hoboken (2008)

Zhurin, V.V., Kaufman, H.R., Robinson, R.S.: Physics of closed drift thrusters. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 8, R-1 (1999)

Keidar, M., Boyd, I.D.: Effect of a magnetic field on the plasma plume from Hall thrusters. J. Appl. Phys. 86, 4786 (1999)

Choueiri, E.Y.: Plasma oscillations in Hall thrusters. Phys. Plasmas 8, 1411 (2001)

Kapulkin, A., Behar, E.: Ion beam instability in hall thrusters. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 43, 1 (2015)

Lafleur, T., Baalrud, S.D., Chabert, P.: Characteristics and transport effects of the electron drift instability in Hall-effect thrusters. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 26, 024008 (2017)

Lazurenko, A., Krasnoselskikh, V., Bouchoule, A.: Experimental insights into high-frequency instabilities and related anomalous electron transport in Hall thrusters. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 36, 1977 (2008)

Chable, S., Rogier, F.: Numerical investigation and modeling of stationary plasma thruster low frequency oscillations. Phys. Plasmas 12, 033504 (2005)

Litvak, A.A., Fisch, N.J.: Rayleigh instability in Hall thrusters. Phys. Plasmas 11, 1379 (2004)

Tsikata, S., Cavalier, J., Héron, A., Honoré, C., Lemoine, N., Grésillon, D., Coulette, D.: An axially propagating two-stream instability in the Hall thruster plasma. Phys. Plasmas 21, 072116 (2014)

Frias, W., Smolyakov, A.I., Kaganovich, I.D., Raitses, Y.: Long wavelength gradient drift instability in Hall plasma devices. I. Fluid theory. Phys. Plasmas 19, 072112 (2012)

Barral, S., Makowski, K., Peradzyński, Z., Dudeck, M.: Transit-time instability in Hall thrusters. Phys. Plasmas 12, 073504 (2005)

Frias, W., Smolyakov, A.I., Kaganovich, I.D., Raitses, Y.: Long wavelength gradient drift instability in Hall plasma devices. II. Applications. Phys. Plasmas 20, 052108 (2013)

Tyagi, J., Singh, S., Malik, H.K.: Effect of dust on tilted electrostatic resistive instability in a Hall thruster. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 12, 39 (2018)

Malik, H.K., Singh, S.: Conditions and growth rate of Rayleigh instability in a Hall thruster under the effect of ion temperature. Phys. Rev. E 83, 036406 (2011)

Malik, R., Malik, H.K.: Compressive solitons in a moving e-p plasma under the effect of dust grains and an external magnetic field. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 7, 65 (2013)

Tomar, R., Bhatnagar, A., Malik, H.K., Dahiya, R.P.: Evolution of solitons and their reflection and transmission in a plasma having negatively charged dust grains. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 8, 138 (2014)

Kumar, R., Malik, H.K., Singh, K.: Effect of dust charging and trapped electrons on nonlinear solitary structures in an inhomogeneous magnetized plasma. Phys. Plasmas 19, 012114 (2012)

Saha, A., Pal, N., Saha, T., Ghorui, M.K., Chatterjee, P.: A study on dust acoustic traveling wave solutions and quasiperiodic route to chaos in nonthermal magnetoplasmas. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 10, 271 (2016)

Javan, N.S.: Negative and positive dust grain effect on the modulation instability of an intense laser propagating in a hot magnetoplasma. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 11, 235 (2017)

Tyagi, J., Malik, H.K., Elskens, Y., Lemoine, N., Doveil, F.: Low frequency resistive instability in a dusty Hall thruster plasma. arXiv:1709.04200 (2017)

Sabetkar, A., Dorranian, D.: Effect of obliqueness and external magnetic field on the characteristics of dust acoustic solitary waves in dusty plasma with two-temperature nonthermal ions. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 9, 141 (2015)

Sikdar, A., Khan, M.: Effects of Landau damping on finite amplitude low-frequency nonlinear waves in a dusty plasma. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 11, 137 (2017)

El-Hanbaly, A.M., El-Shewy, E.K., Sallah, M., Darweesh, H.F.: Linear and nonlinear analysis of dust acoustic waves in dissipative space dusty plasmas with trapped ions. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 9, 167 (2015)

Chahal, B.S., Ghai, Y., Saini, N.S.: Low-frequency shock waves in a magnetized superthermal dusty plasma. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 11, 181 (2017)

Shahmansouri, M.: Gradient effects on dust lattice waves in paramagnetic dusty plasma crystals. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 6, 2 (2012)

Tomar, R., Malik, H.K., Dahiya, R.P.: Reflection of ion acoustic solitary waves in a dusty plasma with variable charge dust. J. Theor. Appl. Phys. 8, 126 (2014)

Wei, L., Jiang, B., Wang, C., Li, H., Yul, D.: Characterization of coupling oscillation in Hall thrusters. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 18, 045020 (2009)

Barral, S., Ahedo, E.: Low-frequency model of breathing oscillations in Hall discharges. Phys. Rev. E 79, 046401 (2009)

Esipchuck, Y.V., Tilinin, G.N.: Drift instability in a Hall-current plasma accelerator. Sov. Phys. Tech. Phys. 21, 417 (1976)

Litvak, A.A., Fisch, N.J.: Resistive instabilities in Hall current plasma discharge. Phys. Plasmas 8, 648 (2001)

Singh, S., Malik, H.K., Nishida, Y.: High frequency electromagnetic resistive instability in a Hall thruster under the effect of ionization. Phys. Plasmas 20, 102109 (2013)

Singh, S., Malik, H.K.: Growth of low-frequency electrostatic and electromagnetic instabilities in a Hall thruster. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 39, 1910 (2011)

Malik, H.K., Singh, S.: Resistive instability in a Hall plasma discharge under ionization effect. Phys. Plasmas 20, 052115 (2013)

Singh, S., Malik, H.K.: Role of ionization and electron drift velocity profile to Rayleigh instability in a Hall thruster plasma. J. Appl. Phys. 112, 013307 (2012)

Smirnov, A., Raitses, Y., Fisch, N.J.: Plasma measurements in a 100 W cylindrical Hall thruster. J. Appl. Phys. 95, 2283 (2004)

Hagelaar, G.J.M., Bareilles, J., Garrigues, L., Boeuf, J.P.: Role of anomalous electron transport in a stationary plasma thruster simulation. J. Appl. Phys. 93, 67 (2003)

Smirnov, A., Raitses, Y., Fisch, N.J.: Parametric investigation of miniaturized cylindrical and annular Hall thrusters. J. Appl. Phys. 92, 5673 (2002)

Acknowledgement

The Indo-French Centre for the Promotion of Advanced Research (IFCPAR/CEFIPRA), New Delhi (Proj-5204-3/RP03052), is gratefully acknowledged for providing the financial assistance to conduct this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tyagi, J., Sharma, D. & Malik, H.K. Discussion on Rayleigh equation obtained for a Hall thruster plasma with dust. J Theor Appl Phys 12, 227–233 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40094-018-0300-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40094-018-0300-5