Abstract

Charges of religion-related employment discrimination have doubled in the past decade. Multiple factors are likely contributing to this trend, such as the increased religious diversity of the US population and the increased interest of employees and some employers in bringing religion to work. Using national survey data we examine how the presence of religion in the workplace affects an individual’s perception of religious discrimination and how this effect varies by the religious tradition of the individual. We find that the more an individual reports that religion comes up at work, the more likely it is that the individual will perceive religious discrimination. This effect remains even after taking into account the individual’s own religious tradition, religiosity, and frequency of talking to others about religion. This effect is stronger, however, for Catholics, Mainline Protestants, and for the religiously unaffiliated. In workplaces where religion is said to never come up these groups are among the least likely to perceive religious discrimination. Jews, Muslims, Hindus, and Evangelical Protestants are more likely to perceive religious discrimination in the workplace even if they say that religion never comes up at work, which makes the effect of exposure to religion in the workplace weaker for these groups. These results show that keeping religion out of the workplace will largely eliminate perceptions of religious discrimination for some groups, but for other groups the perceptions will remain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Other factors they highlight include legal uncertainties surrounding religion in the workplace and the unique nature of religion relative to race, sex, age, and other categories protected from employment discrimination.

Some of the research we will review looked at experienced or actual discrimination, such as through differential interview rates in field experiments. Other research looks at self-reported discrimination that is more akin to perceptions of discrimination. As we will discuss, our own research is more the latter than the former.

The 2003 American Mosaic Project survey (Hartmann et al. 2003) did ask a national sample of respondents more generally, “Have you ever experienced any discrimination because of your religion?” Note that this question is not specifically about workplace discrimination. Hammer et al. (2012) did ask a volunteer sample of self-identified atheists specifically about experiences with being “denied employment, promotion, or educational opportunities because of my Atheism.” Similarly, Cragun et al. (2012) asked a sample of individuals identifying as non-religious in the American Religious Identification Survey whether, “In the past 5 years, have you personally experienced discrimination because of your lack of religious identification or affiliation in any of the following situations: in your workplace.” Both of these latter studies are obviously limited in the population that they represent.

Drydakis (2010) conducted a similar study in Greece and find that religious minorities, particularly Jehovah’s Witnesses, evangelicals, and Pentecostals, were less likely than Greek Orthodox individuals to receive a job interview even when their applications were identical.

It is important to recognize that this is in relation to the average workplace in the United States. There are undoubtedly specific workplaces or even occupations in which the predominant religion amongst employees is Muslim, atheist, or some other non-Christian tradition. It would be valuable for future research to examine such contexts.

The specific question they asked was, “In the past 5 years, have you personally experienced discrimination because of your lack of religious identification or affiliation in any of the following situations: in your workplace.” They did not ask this question of the religious respondents in their sample.

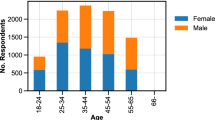

The specific benchmarks are for gender, race and Hispanic ethnicity, education, household income, region, household internet access, and household primary language.

The offered choices included thirteen options, including Just a Christian, Eastern Orthodox, Buddhist, Hindu, Agnostic, and Atheist, in addition to those mentioned in the question wording.

Of course, this assumption is a probabilistic one. There may be examples of individuals who talk to others about religion a great deal outside of work but feel like such talk is inappropriate in the workplace. It is possible that adherence to such a norm might vary by religious tradition, workplace, or other factors. This would be an issue worth examining in future research.

Ideally, we would like to have many more measures of religious expression, such as measures of wearing religious jewelry, clothing, displaying religious symbols or texts, and so forth. Unfortunately, the survey data do not have such measures.

One limitation of these religiosity measures is that they are most applicable to the religious population. For the non-religious it might be ideal to have questions that might serve as similar proxies. These questions might ask about the frequency of visiting certain websites or reading certain books associated with, say, atheism.

Since these religiosity items are clearly going to be correlated with each other, we examined variance inflation factors to assess for potential collinearity problems. None of these inflation factors were above 3.0, which is well below the typical level of concern (Regression with Stata 2016).

As a reader noted, religion coming up at work could be a function of the respondent’s own willingness to talk to others about his or her religion, which we also include a measure of in the analysis. We examined whether these two measures would be too highly correlated to include in the same models. The correlation is .33 (p < .01). While these two measures are related, they do not seem to be prohibitively correlated for the purpose of including both in the analysis.

References

Abercrombie & Fitch Liable for Religious Discrimination in EEOC Suit, Court Says. 2013. San Francisco, CA: U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Retrieved 24 Feb 2015. (http://eeoc.gov/eeoc/newsroom/release/9-9-13.cfm).

Acquisti, Alessandro and Fong, Christina M. 2014. An experiment in hiring discrimination via online social networks. Available at Social Science Research Network. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2031979.

Allport, Gordon W. 1954. The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Aquino, Karl, Steven L. Grover, Murray Bradfield, and David G. Allen. 1999. The effects of negative affectivity, hierarchical status, and self-determination on workplace victimization. Academic of Management Journal 42(3): 260–272.

Arthur, Linda B. 1999. Religion, dress and the body. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Baker, Joseph O’Brian, and Buster Smith. 2009a. None too simple: Examining issues of religious nonbelief and nonbelonging in the United States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 48(4): 719–733.

Baker, Joseph O., and Buster Smith. 2009b. The nones: Social characteristics of the religiously unaffiliated. Social Forces 87(3): 1251–1263.

Baylor University. 2007. The Baylor religion survey, wave II. Waco, TX: Baylor Institute for Studies of Religion. (producer).

Banerjee, Neela. 2006. At bosses’ invitation, chaplains come into workplace and onto payroll. The New York Times, 4 Dec A16. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/04/business/04chaplain.html.

Bierman, Alex. 2006. Does religion buffer the effects of discrimination on mental health? Differing effects by race. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 45(4): 551–565.

Bowling, Nathan A., and Terry A. Beehr. 2006. Workplace harassment from the victim’s perspective: A theoretical model and meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 91(5): 998–1012.

Boynton, Linda Louise. 1989. Religious orthodoxy, social control and clothing: Dress and adornment as symbolic indicators of social control among holdeman mennonite women. Presentation at the Annual Meeting of the American Sociological Association.

Chang, Linchiat, and Jon A. Krosnick. 2009. National surveys via RDD telephone interviewing versus the internet: Comparing sample representativeness and response quality. Public Opinion Quarterly 73(4): 641–678.

“Charge Statistics.” U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. http://eeoc.gov/eeoc/statistics/enforcement/charges.cfm.

Conlin, Michelle. 1999. Religion in the workplace: The growing presence of spirituality in corporate America. Business Week, 150–158.

Cragun, Ryan T., Barry Kosmin, Ariela Keysar, Joseph H. Hammer, and Michael Nielsen. 2012. On the receiving end: Discrimination toward the nonreligious in the United States. Journal of Contemporary Religion 27(1): 105–127.

de Castro, Arnold B., Gilbert C. Gee, and David T. Takeuchi. 2008. Workplace discrimination and health among Filipinos in the United States. American Journal of Public Health 98(3): 520–526.

Dean, James Joseph. 2013. Heterosexual masculinities, anti-homophobias, and shifts in hegemonic masculinity: The identity practices of black and white heterosexual men. The Sociological Quarterly 54(4): 534–560.

Deitch, Elizabeth A., Adam Barsky, Rebecca M. Butz, Suzanne Chan, and Arthur P. Brief. 2003. Subtle yet significant: The existence and impact of everyday racial discrimination in the workplace. Human Relations 56(11): 1299–1324.

D’Augelli, Anthony R., Neil W. Pilkington, and Scott L. Hershberger. 2002. Incidence and mental health impact of sexual orientation victimization of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths in high school. School Psychology Quarterly 17: 148–167.

Doan, Long, Annalise Loehr, and Lisa R. Miller. 2014. Formal rights and informal privileges for same-sex couples: Evidence from a national survey experiment. American Sociological Review 79(6): 1172–1195.

Drydakis, Nick. 2010. Religious affiliation and employment bias in the labor market. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 49: 477–493.

Edgell, Penny, Joseph Gerteis, and Douglas Hartmann. 2006. Atheists as ‘other’: Moral boundaries and cultural membership in American Society. American Sociological Review 71(2): 211–234.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Abercrombie & Fitch Stores, Inc. Supreme Court of the United States. No 14-86. Argued 25, 2015—Decided June 1, 2015.

Gebert, Diether, Sabine Boerner, Eric Kearney, James E. King Jr., K. Zhang, and Lynda Jiwen Song. 2014. Expressing religious identities in the workplace: Analyzing a neglected diversity dimension. Human Relations 67(5): 543–563.

Ghaffari, Azadeh, and Ayşe Çiftçi. 2010. Religiosity and self-esteem of Muslim immigrants to the United States: The moderating role of perceived discrimination. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 20(1): 14–25.

Ghumman, Sonia, and Linda Jackson. 2008. Between a cross and a hard place: Religious identifiers and employability. Journal of Workplace Rights 13(3): 259–279.

Ghumman, Sonia, and Linda Jackson. 2010. The downside of religious attire: The Muslim headscarf and expectations of obtaining employment. Journal of Organizational Behavior 31(1): 4–23.

Ghumman, Sonia, Ann Marie Ryan, Lizabeth A. Barclay, and Karen S. Markel. 2013. Religious discrimination in the workplace: A review and examination of current and future trends. Journal of Business and Psychology 28(4): 439–454.

Goldman, Barry M., Barbara A. Gutek, Jordan H. Stein, and Kyle Lewis. 2006. Employment discrimination in organizations: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Management 32(6): 786–830.

Grammich, Clifford, Kirk Hadaway, Richard Houseal, Dale E. Jones, Alexei Krindatch, Richie Stanley, and Richard H. Taylor. 2012. 2010 U.S. Religion census: Religious congregations & membership study. Association of Statisticians of American Religious Bodies.

Hammer, Joseph H., Ryan T. Cragun, Jesse M. Smith, and Karen Hwang. 2012. Forms, frequency, and correlates of perceived anti-atheist discrimination. Secularism and Nonreligion 1: 43–58.

Hartmann, Doug, Penny Edgell and Joseph Gerteis. American mosaic project: A national survey on diversity. Datafile and codebook. www.thearda.com. Accessed 2003.

Hein, Jeremy. 2000. Interpersonal discrimination against Hmong Americans: Parallels and variation in microlevel racial inequality. The Sociological Quarterly 41(3): 413–429.

Hicks, Douglas A. 2003. Religion and the workplace: Pluralism, spirituality, leadership. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jasperse, Marieke, Colleen Ward, and Paul E. Jose. 2012. Identity, perceived religious discrimination, and psychological well-being in Muslim immigrant women. Applied Psychology 61(2): 250–271.

Kelly, Eileen P. 2008. Accommodating religious expression in the workplace. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal 20(1): 45–56.

King, Eden B., and Afra S. Ahmad. 2010. An experimental field study of interpersonal discrimination toward Muslim job applicants. Personnel Psychology 63(4): 806–881.

Madera, Juan M., Eden B. King, and Michelle R. Hebl. 2012. Bringing social identity to work: The influence of manifestation and suppression on perceived discrimination, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 18(2): 165–170.

McDannell, Colleen. 1995. Material Christianity: Religion and popular culture in America. Hartford, CT: Yale University Press.

Miller, Lisa R., and Eric Anthony Grollman. 2015. The social costs of gender nonconformity for transgender adults: Implications for discrimination and health. Sociological Forum 30(3): 809–831.

Mitroff, Ian I., and Elizabeth A. Denton. 1999. A spiritual audit of corporate America: A hard look at spirituality, religion, and values in the workplace. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Inc.

Mythen, Gabe, Sandra Walklate, and Fatima Khan. 2009. ‘I’m a Muslim, but I’m not a Terrorist’: Victimization, risky identities and the performance of safety. British Journal of Criminology 49: 736–754.

Pavalko, Eliza K., Krysia N. Mossakowski, and Vanessa J. Hamilton. 2003. Does perceived discrimination affect health? Longitudinal relationships between work discrimination and women’s physical and emotional health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44(1): 18–33.

Pedulla, David S., and Sarah Thebaud. 2015. Can we finish the revolution? Gender, work-family ideals, and institutional constraint. American Sociological Review 80(1): 116–139.

Peek, Lori. 2010. Behind the backlash: Muslim Americans after 9/11. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Pettigrew, Thomas F. 1998. Intergroup contact theory. Annual Review of Psychology 49: 65–85.

Putnam, Robert D., and David E. Campbell. 2010. American grace: How religion divides and unites US. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Regression with Stata. UCLA: Statistical Consulting Group. http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/stata/webbooks/reg/chapter2/statareg2.htm. Accessed 12 Jan 2016.

Rippy, Alyssa, and Elana Newman. 2006. Perceived religious discrimination and its relationship to anxiety and paranoia among Muslim Americans. Journal of Muslim Mental Health 1(1): 5–20.

Roberts, Andrea, Margaret Rosario, Natalie Slopen, Jerel P. Calzo, and S. Bryn Austin. 2013. Childhood gender nonconformity, bullying victimization, and depressive symptoms across adolescence and early adulthood: An 11-year longitudinal study. Journal of the American Academy of Adolescent Psychiatry 52: 143–152.

Shachtman, Noah. 2013. In Silicon valley, meditation is no fad. It could make your career. Wired. https://www.wired.com/2013/06/meditationmindfulness-silicon-valley.

Smith, Tom W. 2002. Religious diversity in America: The emergence of Muslims, Buddhists, Hindus, and others. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 41: 577–585.

Smith, Tom W., Peter V. Marsden, and Michael Hout. 2016. General social surveys, 1972–2014. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center.

Snape, Ed, and Tom Redman. 2003. Too old or too young? The impact of perceived age discrimination. Human Resource Management Journal 13(1): 78–89.

Steensland, Brian, Lynn D. Robinson, W. Bradford Wilcox, Jerry Z. Park, Mark D. Regnerus, and Robert D. Woodberry. 2000. The measure of American religion: Toward improving the state of the art. Social Forces 79(1): 291–318.

Wallace, Michael, Bradley R.E. Wright, and Allen Hyde. 2014. Religious affiliation and hiring discrimination in the American South: A field experiment. Social Currents 1(2): 189–207.

Widner, Daniel, and Stephen Chicoine. 2011. It’s all in the name: Employment discrimination against Arab Americans. Sociological Forum 26(4): 806–823.

Wright, Bradley R.E., Michael Wallace, John Bailey, and Allen Hyde. 2013. Religious affiliation and hiring discrimination in New England: A field experiment. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 34: 111–126.

Wuthnow, Robert. 2004. The challenge of diversity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 43: 159–170.

Wuthnow, Robert. 2005. America and the challenges of religious diversity. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Wuthnow, Robert, and Conrad Hackett. 2003. The social integration of practitioners of non-western religions in the United States. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 42: 651–667.

Acknowledgements

Research for this article is part of the Religious Understandings of Science Study, funded by the John Templeton Foundation (Grant 38817, Elaine Howard Ecklund, principal investigator).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Scheitle, C.P., Ecklund, E.H. Examining the Effects of Exposure to Religion in the Workplace on Perceptions of Religious Discrimination. Rev Relig Res 59, 1–20 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-016-0278-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13644-016-0278-x