Abstract

Key message

Over-yielding of stand biomass did not occur in a tree polyculture comprised of Betula pendula, Alnus glutinosa and Fagus sylvatica selected for contrasting traits. This was due to antagonistic interactions between the component species. Fine root dynamics and soil C stocks were unaffected by species mixture.

Context

Increasing CO2 fixation in tree biomass through afforestation and forest management actions has potential for cost-effective climate mitigation. The influences of tree mixture on biomass production and subsequent soil C accumulation in polyculture still remain uncertain.

Aims

We studied the polyculture of Alnus glutinosa (L.) Gaertn, Betula pendula Roth and Fagus sylvatica L. in a plantation forest to examine the effectiveness of species mixtures as a tool for increased biomass production and soil C accumulation.

Methods

Tree biomass was estimated by developing species-specific allometric models and 3 years tree measurement. Fine root biomass and production were estimated by root coring and root-mesh methods. The ‘relative yield of mixture’ approach was used to examine the mixture effect.

Results

In mixture, an additive effect was observed in A. glutinosa (13% increase in basal diameter relative to the monoculture); however, there was no overall effect of mixture on total standing biomass due to the suppression of F. sylvatica (2.75 g m−2 reduction in woody biomass). Fine root biomass production showed no mixture effect. The quantity and quality of soil C (top 0.5 m) was not affected by tree mixture.

Conclusion

We conclude that the contrasting growth responses of the A. glutinosa, B. pendula and F. sylvatica in polyculture resulted in no over-yielding of standing biomass despite the complementary traits of the component species.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Afforestation and reforestation are recommended as low-cost strategies to mitigate the anthropogenic elevation of CO2 and the associated global impacts of climate change (Valatin and Price 2014). Increased tree growth and biomass production due to higher tree species diversity has been reported by some investigators, indicating positive impacts on the storage and sequestration of atmospheric C in forest ecosystems (Bielak et al. 2014; Gamfeldt et al. 2013; Hulvey et al. 2013). In plantation forestry, numerous management tools help to maximize growth and biomass production. These include species selection (Nord-Larsen and Meilby 2016; Aravanopoulos 2010), tree composition and diversity (Belote et al. 2011; Pretzsch et al. 2010), plantation design (Kunert and Cárdenas 2015; Goelz 2001), stand density (Vanclay 2006) etc. Nonetheless, our mechanistic understanding of species interactions within plant communities is poor and the degree to which species polyculture enhances biomass production and contributes to ecosystem C stocks remains unclear.

The potential advantage of species interactions in polyculture (in terms of biomass growth when compared with monoculture) involves competitive reduction and facilitation mechanisms (Forrester et al. 2005). Nonetheless, additive/antagonistic mixture effects resulting in no change/lower biomass production in polyculture vs. monoculture may occur due to lack of sufficient complementarity or through competition between species (Pretzsch et al. 2010; Kelty and Cameron 1995). In a recent study, Tobner et al. (2016) reported that 80% of the diversity issues in mixed species plantations were driven by the selection effect and the remaining 20% were influenced by complementarity effect in a young tree diversity experiments (www.treedivnet.ugent.be). Species density and the ratio of component species in polyculture can influence the interspecific interactions and ultimately affect stand development (Kelty 2006). Similarly, a decrease in competition reduction was reported by Pretzsch et al. (2012) when different spatial mixing patterns were used in a polyculture stand of Picea abies and Fagus sylvatica. These results indicate that biomass over-yielding may not be achieved in polyculture due to inappropriate silvicultural interventions (Vanclay 2006). Like aboveground biomass, polyculture can influence the biomass and vertical distribution of fine root due to niche complementarity (Tobner et al. 2016). For example, Laclau et al. (2013) reported that 27% higher total fine root biomass in a mixed stand of Eucalyptus grandis and Acacia mangium than in monoculture following a replacement series (50:50) in a 5-year-old mixed plantation. Contrasting results of no over-yielding in fine root biomass were observed by Jacob et al. (2014) in an 8-year-old temperate mixed forest of Picea abies, Pseudotsuga menziesii, Fagus sylvatica and Quercus robur. However, it is not clear whether the belowground responses synchronize the aboveground biomass interactions, because only few studies addressed above- and belowground simultaneously. Thus, a comprehensive assessment of above- and belowground tree biomass is crucial for a better understanding of the role of tree polyculture on ecosystem C stocks.

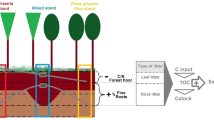

Tree species identity can enhance soil C stock through aboveground litter production and fine root turnover under the influence of soil and site characteristics. The magnitude of C inputs to soil by aboveground litter flux may depend on the quality and quantity of litter, biodegradation and soil properties (Jandl et al. 2007). Dead roots and rhizodeposition of tree root systems are likely more potential to stabilize soil C than aboveground litter due to slow decay rate and mineral interactions (Vesterdal et al. 2013). In addition, many previous studies reported that the stock and stability of soil C under these processes fluctuate over stand age (Chen et al. 2013). In general, most of the factors affecting C inputs are species specific; therefore, the impacts of tree plantation on soil C storage are highly variable depending on the species selection. Similarly, the effect of species mixture on mineral soils C of new plantings is inconsistent. For example, Forrester et al. (2013) reported the positive influence of an A. mearnsii and E. globulus admixture on soil C stock in a young plantation forest. However, Wang et al. (2009) found no significant differences in soil C under mixed plantation of Chinese fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata (Lamb.) and broadleaved Alnus cremastogyne Burkill in an afforested land after 15 years. Contrasting results indicate that the link between tree plantation and soil C might be regulated by multiple spatial and temporal factors including tree functional traits.

Many earlier studies on mixture effect examined the interactions between two component species (Forrester et al. 2005; Laclau et al. 2013; Bielak et al. 2014). However, a three-species interaction is more challenging because of the variability in competition and growth rates. In the present study, we used two fast-growing species with a late successional tree in the polyculture stand to study whether the interactions of these contrasting traits affect the biomass production and soil C stocks compared with monoculture conditions. Assessing forest biomass currently lacks methodological robustness. Since our study was confined to a single location, however, the traditional approach of tree harvesting was followed to estimate aboveground biomass, which is a more reliable method than others (Weiskittel et al. 2015). We measured litter fall to evaluate the link between active biomass and soil organic C stock under the various species compositions. The study was designed to investigate whether the polyculture of Betula pendula Roth, Alnus glutinosa (L.) Gaertn and Fagus sylvatica L. increases the accumulation of tree biomass and affects soil C stocks. We hypothesised that (i) combination of trees having different functional traits produces more woody and fine root biomass in polyculture than monoculture of each species. We predicted that the growth of each species would be increased in polyculture (species level), which would eventually increase standing biomass (stand level). (ii) Establishment of forests composed of tree polycultures positively affects the soil organic C stock.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study sites and soil

Henfaes Research Centre, the research station of Bangor University, is located in the village of Abergwyngregyn, 12 km east of Bangor City, North Wales, UK (geographic position 53° 14 N, 4° 01 W and National Grid: SH 653741GB). The soil developed under more or less well-drained conditions (noncalcareous) and from unconsolidated parent materials, traditionally grouped in Britain as Brown earth (Clarke 1940). This is classified as Dystric Cambisols according to the FAO system and recognized as the Rheidol series (Teklehaimanot et al. 2002). The topsoil is slightly acidic (pH 5.4), loamy in texture, brown and originated from glaciated shales, sandstone and mudstone at the upper portion and from glaci-fluvial deposits of clay, silt, sand and gravels at the lowland areas. The climate of the area is Hyperoceanic, and the seasonal temperature varies between − 3 and 10 °C in winter and 12 and 25 °C in summer; the mean annual rainfall is about 1000 mm (Campbell Automatic Weather Station, Campbell Scientific Ltd., Shepshed, UK).

2.2 Afforestation

The BangorDiverse site was established on 2.36 ha of former agricultural land in March 2004, with a range of broadleaved tree species. The site consists of two adjacent blocks (Fig. 1) that were previously used for growing oil seed rape and as a tree nursery. Previous to that, the area was grassland. The plantation fields were established in four replicated plots of single species or two- and three-species mixtures of Alnus glutinosa L., Betula pendula Roth, Fagus sylvatica L., Fraxinus excelsior, Acer pseudoplatanus L., Castanea sativa Mill. and Quercus robur L. In the present study, we used A. glutinosa, B. pendula and F. sylvatica, which were selected due to their contrasting shade tolerance, successional chronology and to represent a range of taxonomic, physiological and ecological types. Two replicated plots of each species were sited in each block (hence, four plots per species) and the minimum distance between any two plots of the same composition was 35 m. The site was planted with 60 cm saplings of each species with an inter-tree spacing of 1 m (10,000 trees ha−1). A replacement series (with inter-tree spacing constant between treatments) with systematic hexagonal planting design (Aguiar et al. 2001) was used to maximize the mixture effect in the four polyculture plots, where each tree was surrounded by six equidistant neighbour trees (two conspecific individuals, one and three individuals of the other two species) (Fig. 1). In the current study, we used 16 plots of A. glutinosa, B. pendula and F. sylvatica monoculture and the polyculture of these three species with equal proportion of component tree species. Hence, each species of monoculture and polyculture had four replicated plots (three single species and one mixed × 4 = 16 plots; details of plantation plots are presented in Table 1). The forest floor vegetation included scattered grass and moss with a very few perennial herbs such as Utrica dioica, because of canopy cover of densely planted fast growing trees.

Experiment site and plantation design. a Twelve monoculture of B. pendula (Bi), A. glutinosa (Al) and F. sylvatica (Be) and four three-species polyculture (M) plots, distributed over two plantation blocks. b Sketch of hexagonal planting design in three-species polyculture. Each plant was surrounded by six neighbours of two conspecific individuals, one and three of the other two species

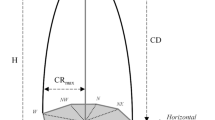

2.3 Allometric equations for biomass

Ten trees from each species (a total of 30 trees) were harvested in March 2010 to give a range of diameter at breast height (DBH, i.e. at 1.3 m above the ground level) to develop the allometric models. Two trees from each monoculture plots (2 × 3 species × 4 replicates) and one from mixed plots of each two blocks (1 × 3 species × 2 blocks) were randomly selected, given the DBH ranges of 14.5–75.4, 29.9–91.5 and 15.0–50.2 mm for B. pendula, A. glutinosa and F. sylvatica, respectively. Before harvesting the trees, height, DBH and basal diameter (at 22.5 cm) were measured using a telescopic measuring pole and digital callipers. As most of the trees were not perfectly round, the geometric mean of the highest and lowest diameter was calculated to estimate DBH.

After harvesting the bole, branches, dry leaves (most of the trees were leafless, hence the biomass was termed as woody biomass) and catkins were separated. The fresh weight of all separated parts was measured using an electrical balance (OHAUS, 5000 Series, Xtreme W, T51XW), and the dry mass of tree components was determined from oven-dried subsamples. For each species, four tree parameters (DBH, basal diameter, branch dry-mass and tree height) were considered to predict the aboveground woody biomass by developing allometric models. Based on the goodness-of-fit indices, basal diameter models were selected for B. pendula and F. sylvatica and the DBH model for A. glutinosa. The selected two parameters (basal diameter and DBH) were checked with three non-linear models, viz. power, exponential and logarithm, of which power models were found as the best fit for predicting woody biomass. The following three equations were developed for biomass estimation (Appendix 1 and Appendix 2):

-

i)

For B. pendula Y = 0.0002 d2.3893

-

ii)

For A. glutinosa Y = 0.0006 D2.2775

-

iii)

For F. sylvatica Y = 0.0002 d2.577

where Y is woody biomass (kg), d is basal diameter (mm) and D is diameter at breast height (mm).

The height, DBH and basal diameter of all trees in 16 plots were measured for the years 2008, 2009 and 2010 (on average, a total of 1805 trees were measured during March–May of each year). To estimate the standing biomasses of each plot, the basal diameter and DBH data of individual trees were used for the above-mentioned allometric equations.

2.4 Litter collection

Litter was collected using 40 litter traps (35 × 35 cm plastic pot with square opening), placing two traps in each single and four traps in mixed plots. These were later mixed to one sample per plot, constituted 0.49 and 0.25 m2 of trapping area in each mixed and monoculture plots, respectively. Annual litter was collected at 15-day intervals in summer and at 1-month intervals in other seasons. Collected fresh litter was sorted into leaves, branches (< 2 mm diameter), twigs and catkins oven dried.

2.5 Fine root biomass

Fine root biomass (≤ 2 mm) was sampled in April–May 2008 and 2009 before the start of the growing season using a soil corer (8 cm diameter) from 16 mono- and mixed species plots. Core samples (30 cm, split into three depths viz. 0–10, 10–20 and 20–30 cm) were collected from three randomly selected locations of each plot at an equal distance from surrounding trees. In mixed-species plots, samples were collected at a point equidistant from B. pendula, A. glutinosa and F. sylvatica trees. Fine root biomass in each core was calculated as grammes per square metre, and the average of three cores was presented as biomass per plot. After harvesting, the samples were transported to the laboratory and stored at 4 °C until washing. The whole core sample was washed through a set of mesh sieves (2.0–0.5 mm) with tap water and the fine roots were sorted following the handpicking approach based on the physical characteristics of the root matrix. Non-tree roots such as herbaceous roots were soft (non-lignified) and lighter in colour than tree roots, grass roots were white, soft and more elastic, while the moss roots were black and rigid. Some non-tree roots had fine root hairs which were absent in three tree roots in our study. To distinguish the roots of the different tree species, fine roots were compared with ‘specimen roots’ of three species collected during the field studies. The roots were distinguished based on colour, texture and branching pattern, often using a magnifying glass. The sorted fine roots within each soil core were dried at 70 °C till constant weight and dry mass was recorded.

2.6 Root production and turnover

To estimate annual fine root (< 2 mm) production, a root-mesh technique (Godbold et al. 2003; Lukac and Godbold 2010) was used. In this method, a nylon mesh strip (7 × 25 cm, 1 mm mesh size) was pushed into the ground vertically with a steel blade and hammer. Four strips were inserted at 50 cm distance from each target trees (three trees in each monoculture and three component trees in each polyculture plots were randomly selected for this experiment) and retrieved after two intervals (6 months each). The fine roots that crossed through the net were collected and dry mass was determined. The roots of other species (non-tree species or other tree species in mixed plot) were carefully separated following the methods described in the previous section. The root biomass turnover rate was calculated as annual root production divided by the mean standing root biomass.

2.7 Mixture effect in polyculture

To determine the species interaction in polyculture, the standing aboveground woody biomass in polyculture plots (measured) was compared with a theoretical mixture (predicted) calculated from the biomass of component species growing in the monoculture plots following relative yield of mixtures approach (Wilson 1988; Smith et al. 2013). The following equation shows the predicted biomass (Bmix) calculation from the biomass of component species in monoculture, based on the tree number of each species in polyculture (in this case, the contribution of each species in polyculture was one third):

2.8 Soil sampling and measuring C and N storage

Representative soil samples were collected in different soil layers by excavating pits (100 × 100 × 100 cm) in all plantation plots during September 2008. Sixteen pits (4 × 3 monoculture and 4 × 1 polyculture) were excavated at the middle of each plot, equidistant from surrounding trees (in polyculture, equal distance from A. glutinosa, B. pendula and F. sylvatica). Composite soil samples were collected from seven layers (0–10, 10–0, 20–30, 30–40 and 40–50 cm soil depth) of each pit. The bulk density of the soil was determined by core (5.5 cm diameter) sampling method with stone correction (volume of stone was estimated by water replacement process). Soil organic C and N were determined using a CN analyser (TruSpec® CN, LECO Inc.), and the stocks were estimated using bulk density data (soil properties are presented in Appendix 3).

2.9 Statistical analysis

Allometric models

Each of the three monoculture and a polyculture forests had four replicated plots (n = 4). Tree sampling was stratified into three DBH classes (14–75, 29–91 and 15–50 mm for B. pendula, A. glutinosa and F. sylvatica, respectively), and from each class, ten trees were randomly selected for harvest (n = 10). Species-specific allometric models were developed by linking four independent variables (basal diameter, DBH, height and branch dry mass) with aboveground woody biomass using the following non-linear power regression model (Smith et al. 2013):

where Y is the woody biomass of the tree, x is a tree variable (DBH, basal diameter, tree height or branch dry mass), a and b are regression coefficients (log transformed version: ln Y = a + b ln x with a correction factor CF). In addition, we examined the exponential (Y = a ebx) and the logarithmic (Y = a + b ln x) models to check the relationship between woody biomass and DBH, basal diameter (data not shown). To evaluate the performance to various models, we used three ‘goodness-of-fit’ criteria viz. coefficient of determination (R2), F-ratio of the regression and the root mean squared error (RMSE) of the models. Development of the models, curve fit and correlation analyses were performed by the data analytical software SigmaPlot 12 (Systat Software Inc.)

Analysis of variance

A series of one-way between-measure analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed to test for differences in tree and soil measures. All data were checked for normality (Shapiro-Wilk test, because the number of observation was small) and the homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test). In case the assumptions for the ANOVA were not met, data were log-transformed. The dependent variables were woody biomass, fine root biomass, root production, root turnover and soil organic C and N stocks (within measures). Independent variable or grouping variable (factor) was species type in forest stands with four attributes viz. Betula, Alnus and Fagus and mixture (between measures). Tukey’s HSD was used for post hoc test of multiple comparisons of the means among four factors.

T test

An independent sample t test was performed to compare the actual and predicted biomass in the mixed-species plots, assuming the actual and predicted biomass as two different groups of cases. Similarly, species-level biomass, tree height and DBH between mono- and polyculture plots were examined by t test. ANOVA and t test were conducted with SPSS 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL), and the level of significance P < 0.05 was accepted in all cases.

Correlations

Scattered plots were used to examine the relationship between soil C stock (dependent variables) and tree components, i.e. woody biomass, litter fall and fine root biomass (independent variables) and expressed by the R2 to assess how much of the variability in soil C stock was shared by those tree inputs (Field 2009).

3 Results

3.1 Tree growth, allometric models and biomass

All growth parameters (height, DBH, basal diameter, basal area) confirmed a significantly lower growth of F. sylvatica in the polyculture stand than in monoculture (Table 1). The basal diameter of A. glutinosa significantly increased in the mixed stand but the increases in DBH and basal area were not statistically significant. The growth of B. pendula was not different between the polyculture and monocultures.

Based on the high R2, F value and the comparatively smaller RMSE than other models, the two-parameter power regression curve was the best fit for the plotted values (Y = a xb) (Table 2). For B. pendula and F. sylvatica, the basal diameter was the best predictor of woody biomass (R2 = 0.997, F = 2746.4 and R2 = 0.985, F = 517.5 for two species, respectively). For A. glutinosa, DBH was the best fit (R2 = 0.995, F = 1491.3).

At the stand age of 4, 5 and 6 years, the production of aboveground woody biomass in the monoculture of B. pendula was similar to A. glutinosa stands (Fig. 2). The biomass of F. sylvatica in monoculture was significantly lower than that of the two other species in all years (Fig. 2). The annual biomass increment rates were 37, 44 and 124% for B. pendula, A. glutinosa and F. sylvatica in years 5 and 12, 24 and 39% in year 6. Despite the highest annual rates of biomass production during those 2 years, F. sylvatica had a significantly lower standing biomass stocks than the other two species.

Aboveground woody biomass in mono- and polyculture stands of B. pendula, A. glutinosa and F. sylvatica at the end of the 4th, 5th and 6th growing seasons. Woody biomass was estimated using species-specific allometric equations, developed by the tree harvesting approach after 6 years of stand age. Bars mean SE (n = 4). Within 1 year, bars without the same indices are significantly different (P < 0.05)

3.2 Mixture effects on biomass in polyculture

At the species level, B. pendula and A. glutinosa exhibited no mixture effect on biomass production, and the differences between polyculture and monoculture (increased in A. glutinosa biomass and decreased in B. pendula) were not statistically significant after 4, 5 and 6 years of plantation (Fig. 3a). However, a significant increase (13%) in basal diameter of A. glutinosa attributed to biomass increasing trend in polyculture stand. On the other hand, the woody biomass of F. sylvatica was significantly reduced in polyculture compared with monoculture over 3 years of experiments (Fig. 3a). Thus, after 6 years, A. glutinosa showed insignificant increase in biomass (2.91 kg m−2 higher than monoculture, P = 0.06) but F. sylvatica demonstrated significantly lower biomass (2.76 kg m−2 lower than monoculture, P = 0.013) (Fig. 3a).

Mixture effects in three-species polyculture (positive and negative values indicate higher and lower biomass in polyculture than monoculture respectively). a Species-level differences in biomass. F. sylvatica showed significant mixture effect (−ve differences) but A. glutinosa and B. pendula had insignificant impacts on biomass. b Stand-level mixture effect. The differences between measured (in polyculture stand) and predicted (calculated from monoculture stands) woody biomass, which were not statistically significant. Bars mean SE (n = 4), Asterisk indicates statistically significant differences

At stand level, the difference between measured values (calculating from polyculture stand) and the predicted values (calculating from three monoculture stands) were very marginal and statistically insignificant (Fig. 3b), indicating the additive mixture effect on standing biomass.

3.3 Fine root biomass, production and turnover rate

Total standing fine root biomass measured to a depth of 30 cm ranged between 59.3 ± 21.9 and 91.0 ± 38.4 g−2 (Table 3). Overall, there was a significant effect of species (P = 0.045) and depth (P = 0.001), but no species × depth interaction was observed. The fine root biomass of F. sylvatica in the 0–10-cm layer was significantly lower than that of A. glutinosa (P = 0.036). The greatest proportion of total fine roots (78–82%) was distributed in the upper 0–20 cm soil layer of the polyculture. Although the fine root production in A. glutinosa monoculture was substantially higher than both that of F. sylvatica and B. pendula, only the variation with F. sylvatica was statistically significant (P = 0.047). No significant mixture effect was found (Table 3).

3.4 Soil organic C and N

The C stock in F. sylvatica soil was significantly lower than that in B. pendula at 0–10 cm (P = 0.019) and lower than that in B. pendula and A. glutinosa at 10–20 cm soil layers (P = 0.004 and 0.013, respectively), but no effect of species polyculture on soil C was observed (Table 4). Soil N stock did not differ among the four plantations in any layer. Soil organic C stock exhibited stronger relationship with root biomass (R2 = 0.42, P = 0.006) than aboveground biomass and litterfall (Fig. 4).

4 Discussion

Between the two fast-growing trees, no significant variation was observed in standing woody biomass, height and DBH, indicating similar growth of these two species during young age. These results are in accordance with Claessens et al. (2010) that the growth rate of A. glutinosa and B. pendula is very high when young, and their height growth is similar up to the age of 40 years. In contrast, the aboveground woody biomass in F. sylvatica was half that of fast-growing B. pendula and A. glutinosa. F. sylvatica is a shade-tolerant and late successional species, and its low biomass accumulation might be attributed to inherent characteristics of slow juvenile growth.

4.1 Species interactions in polyculture

Species interactions in polyculture can positively affect biomass production only when component species have contrasting growth characteristics and thus competitive reduction occurs (Kelty 2006). In the present study, B. pendula and A. glutinosa are recognized as pioneer, light-demanding and early successional and fast-growing species while F. sylvatica is a shade-tolerant and late successional species. Theoretically, these characteristics can increase growth by developing complementarity in polyculture; however, the negative interactions between two species may happen in the case of interspecific competition. Species-level comparison showed that the understory F. sylvatica has a significantly lower biomass and tree height (52% lower) in polyculture than monoculture. This suggests that, although it is recognized as being shade tolerant and can survive well in the understory, the growth of young F. sylvatica is much higher when directly exposed to sunlight (in monoculture) than growing with diffused light in the understory of a polyculture stand. Although increased A. glutinosa biomass in polyculture was not statistically significant, the quantity was substantial when we compared with decreased biomass of F. sylvatica. The increasing trend in biomass production showed A. glutinosa with a positive growth trend in polyculture. Therefore, our predictions of growth and biomass increase at species level in polyculture were not fully supported by the tree species we used, rather A. glutinosa (increased diameter growth) and F. sylvatica (decreased growth and biomass production) exhibited a contrasting mixture effect whilst B. pendula remained unchanged in polyculture.

4.2 Standing biomass in polyculture

Our study demonstrated no woody biomass over-yielding in polyculture stands, which contrasts with the general expectation of higher growth in such stands compared with monoculture. The measured and predicted (weighted) biomass in our study revealed that the yield in the polyculture stand was perfectly predictable by the values from the three monoculture stands, indicating a purely additive mixture effect on stand-level biomass. However, our species-level analysis revealed that this was not because of similar performances of species in mono- and polycultures but due to an opposite responses of A. glutinosa and F. sylvatica when grown in polyculture systems. This affected the overall stand-level yield performances of these three-species combination leading to an additive effect on woody biomass. Here, we provided evidence of occurring of contrasting interactions simultaneously in polyculture of three broadleaved species.

Although tree species identities in monocultures influenced fine root dynamics, species mixture in polyculture showed no impact on stand-level biomass or fine root production, presumably due to lack of sufficient root complementarity and/or young stand age. Both causes might be true in our experiment where complementarity can be insufficient due to young age of the trees (Rothe and Binkley 2001). This agrees with Domisch et al. (2015), who found no increase in fine root biomass or fine root production in a mixed stand compared with monoculture, suggesting that lack of sufficient root complementarity and young stand age could be the reasons. Our data on vertical root distribution showed that 24% of the fine root system in the polyculture was found at 20–30 cm soil depth compared with 19% at the same depth in monocultures. This could be an indication of niche differentiation due to contrasting rooting traits of the B. pendula and A. glutinosa in polyculture to access soil resources. The combined results of above- and belowground biomass in this study did not support our first hypothesis of increased biomass in the polyculture stands of contrasting trees. But the trees exhibited both a synergistic and antagonistic mixture effects, indicating a complex species interaction in the polyculture systems.

4.3 Tree biomass and soil C and N stocks

A species influence on soil C stock was observed only with F. sylvatica soils in the top layers (0–10 and 10–20 cm). This agrees with previous studies that tree species composition affects soil organic C stock particularly in topsoil (Liu et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2009). There is an agreement that the tree species has enormous effects on the soil, mainly because of the quality and quantity of organic matter inputs through litter fall, root and soil microbial activities (Dawud et al. 2016; Vesterdal et al. 2002). Nonetheless, the impacts may be positive, negative or unpronounced depending on the characteristics of input materials, soil factors and associated C processes. For example, fresh litter inputs can contribute to organic C accumulation in soil but also enhance depletion of the soil C stock through the priming effect in plantation forests (Chen et al. 2015). Differences between SOC storage in the topsoil layers of F. sylvatica and the other two stands were clearly due to the low litter input and fine root production in the slow-growing F. sylvatica, indicating effect of species identity on observed variations (Appendix 4). High soil organic C in mixed stand are generally attributed to high litter inputs (Forrester et al. 2013), hence no obvious variation in soil C was observed between mono- and polyculture stands in the present study.

The stronger relationship between SOC stocks and fine root biomass (R2 = 0.42) indicated higher control of fine roots than of aboveground biomass on the soil C stock at our forest sites. Recent experiments with 13C-labelled leaf and root materials confirmed that C derived from fine roots has more potential for long-term sequestration than foliar C, presumably due to the recalcitrant nature of root compounds (Hu et al. 2016). Contrary with our second hypothesis, the influence of aboveground and fine root biomass, induced by polyculture plantations showed no significant effect on the soil C stock at 50 cm soil depth.

4.4 Limitations regarding stand age and short-term experiments

We quantified mixing effects by comparing mono- and mixed-species stands on the same site conditions; however, the young age of trees and the duration of experiment might limit the implication of the observed changes. The mixing effect may not remain constant during the stand development and the growth ratios of different species may vary over time (Drossler et al. 2015). For example, at the young stage, the fast growing and light demanding species capture light more efficiently, but after canopy closure, the competition for light increases in polyculture stand, which may affect the growth of component species. Similarly mixing effects on soil organic C stock may change with stand development (Liu et al. 2016). Therefore, the effects of species polyculture on tree biomass and soil C at the young stage cannot be generalized over the entire life succession of the species and rather expressed the effects based on the point of evaluation. Clearly, as emphasized by other authors, there is a need for longer-term experiments (Bielak et al. 2014; Liu et al. 2018; Pretzsch et al. 2019).

5 Conclusion

Although tree species with complementary traits were selected, we did not find higher growth or biomass production in polyculture stands. This is contrary with our original hypothesis. The outcome of our experiment may have been influenced by the planting design with a high planting density (1 × 1 m). In our fine-grained mixture (1:1:1), the two fast-growing species dominated the upper canopy and clearly suppressed the F. sylvatica in the understory. The dense planting removed the need for extensive weed control. However, typical management techniques such as thinning may be needed to reduce competition and promote possible positive interactions in polyculture.

Statement of data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Aguiar FC, Ferreira MT, Moreira I (2001) Exotic and native vegetation establishment following channelization of a western Iberian river. Regul River: Res Manage 17:509–526

Aravanopoulos FA (2010) Breeding of fast growing forest tree species for biomass production in Greece. Biomass Bioenergy 34:1531–1537

Belote RT, Prisley S, Jones RH, Fitzpatrick M, de Beurs K (2011) Forest productivity and tree diversity relationships depend on ecological context within mid-Atlantic and Appalachian forests. For Ecol Manage 216:1315–1324

Bielak K, Dudzinska M, Pretzsch H (2014) Mixed stands of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L.) and Norway spruce Picea abies (L.) Karst can be more productive than monocultures. Evidence from over 100 years of observation of long-term experiments. Forest Systems 23:573–589

Chen GS, Yang ZJ, Gao R, Xie JS, Guo JF, Huang ZQ, Yang YS (2013) Carbon storage in a chronosequence of Chinese fir plantations in southern China. Forest Ecol Manag 300:68–76

Chen Y, Liu L, Rao X, Wang X, Liang C, Lin Y, Zhou L, Cai X, Fu S (2015) Carbon storage and allocation pattern in plant biomass among different forest plantation stands in Guangdong, China. Forests 6:794–808

Claessens H, Oosterbaan A, Savill P, Rondeux J (2010) A review of the characteristics of black alder and their implications for silvicultural practices. Forestry 83:163–175

Clarke GR (1940) Soil survey of England and Wales: field handbook. University Press, Oxford

Dawud SM, Raulund-Rasmussen K, Domisch T, Finer L, Jaroszewicz B, Vesterdal L (2016) Is tree species diversity or species identity the more important driver of soil carbon stocks, C/N ratio, and pH? Ecosystems 19:645–660

Domisch T, Finér I, Dawud SM, Vesterdal L, Raulund-Rasmussen K (2015) Does species richness affect fine root biomass and production in young forest plantations? Oecologia 177:581–594

Drossler L, Overgaard R, Eko PM, Gemmel P, Bohlenius H (2015) Early development of pure and mixed species plantations in Snogeholm, southern Sweden. Scand J For Res 30:304–316

Field A (2009) Discovering statistics using SPSS, 3rd edn. SAGE Publications Ltd, London, p 179

Forrester DI, Bauhus J, Cowie AL (2005) On the success and failure of mixed-species tree plantations: lessons learned from a model system of Eucalyptus globulus and Acacia mearnsii. For Ecol Manag 209:147–155

Forrester DI, Pares A, O’Hara C, Khanna PK, Bauhus J (2013) Soil organic carbon is increased in mixed-species plantations of Eucalyptus and nitrogen-fixing Acacia. Ecosystems 16:123–132

Gamfeldt LT, Snall R, Bagchi M, Jonsson L, Gustafsson P, Kjellander MC, Ruiz-Jaen MC et al (2013) Higher levels of multiple ecosystem services are found in forests with more tree species. Nature Communications 4:1340

Godbold DL, Friz HW, Jentschke G, Meesenburg H, Rademacher P (2003) Root turnover and root necromass accumulation of Norway spruce (Picea abies) are affected by soil acidity. Tree Physiology 23:915–921

Goelz JCG (2001) Systematic experimental designs for mixed-species plantations. Native Plants J 2:90–96

Hu YL, Zeng DH, Mab XQ, Chang SX (2016) Root rather than leaf litter input drives soil carbon sequestration after afforestation on a marginal cropland. For Ecol Manag 362:38–45

Hulvey KB, Hobbs RJ, Standish RJ, Lindenmayer DB, Lach L, Perring MP (2013) Benefits of tree mixes in carbon plantings. Nat Clim Chang 3:869–874

Jacob A, Hertel D, Leuschner C (2014) Diversity and species identity effects on fine root productivity and turnover in a species-rich temperate broad-leaved forest. Funct Plant Biol 41:678–689

Jandl R, Lindner M, Vesterdal L, Bauwens B, Baritz R, Hagedorn F, Johnson DW, Minkkinen K, Byrne KA (2007) How strongly can forest management influence soil carbon sequestration? Geoderma 137:253–268

Kelty JM (2006) The role of species mixtures in plantation forestry. For Ecol Manag 233:195–204

Kelty MJ, Cameron I (1995) Plot design for the analysis of species interactions in mixed stands. Commonwealth For Rev 74:322–332

Kunert N, Cárdenas AM (2015) Are mixed tropical tree plantations more resistant to drought than monocultures? Forests 6:2029–2046

Laclau J-P, Nouvellon Y, Reine C, Goncalves JL, Krushe AV, Jourdan C, le Maire G, Bouillet J-P (2013) Mixing Eucalyptus and Acacia trees leads to fine root over-yielding and vertical segregation between species. Oecologia 172:903–913

Liu N, Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao Z, Zhao Y (2016) Tree species composition rather than biodiversity impacts forest soil organic carbon of Three Gorges, southwestern China. Nat Conserv 14:7–24

Liu CLC, Kuchma O, Krutovsky KV (2018) Mixed-species versus monocultures in plantation forestry: Development, benefits, ecosystem services and perspectives for the future. Global Ecology and Conservation 15:e00419. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2018.e00419

Lukac M, Godbold DL (2010) Fine root biomass and turnover in southern taiga estimated by root inclusion nets. Plant Soil 331:505–513

Nord-Larsen T, Meilby H (2016) Effects of nurse trees, spacing, and tree species on biomass production in mixed forest plantations. Scand J For Res 31:592–601

Pretzsch H, Block J, Dieler J, Dong PH, Kohnle U, Nagel J, Spellmann H, Zingg A (2010) Comparison between the productivity of pure and mixed stands of Norway spruce and European beech along an ecological gradient. Ann For Sci 67:1–12

Pretzsch H, Dieler J, Seifert T, Rötzer T (2012) Climate effects on productivity and resource-use efficiency of Norway spruce (Picea abies [L.] Karst.) and European beech (Fagus sylvatica [L.]) in stands with different spatial mixing patterns. Trees 26:1343–1360

Pretzsch H, del Río M, Biber P, Arcangeli C, Bielak K, Brang P, et al (2019) Maintenance of long-term experiments for unique insights into forest growth dynamics and trends: review and perspectives. European Journal of Forest Research, 138(1):165–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10342-018-1151-y

Rothe A, Binkley D (2001) Nutritional interactions in mixed species forest: a synthesis. Can J For Res 31:1855–1870

Smith AR, Lukac M, Hood R, Miglietta F, Godbold DL (2013) Elevated CO2 enrichment induces a differential biomass response in a mixed species temperate forest plantation. New Phyt 198:156–168

Teklehaimanot Z, Jones M, Sinclair FL (2002) Tree and livestock productivity in relation to tree planting configuration in a silvopastoral system in North Wales, UK. Agrofor Syst 56:47–55

Tobner CM, Paquette A, Gravel D, Reich PB, Williams LJ, Messier C (2016) Functional identity is the main driver of diversity effects in young tree communities. Ecol Lett 19:638–647

Valatin G, Price C (2014) How cost-effective is forestry for climate change mitigation? In: Fenning T (ed) Challenges and opportunities for the world’s forests in the 21st century. Forest sciences, vol 81. Springer Science, Dordrecht, pp 297–339

Vanclay JK (2006) Experiment designs to evaluate inter- and intra-specific interactions in mixed plantings of forest trees. For Ecol Manag 233:366–374

Vesterdal L, Ritter E, Gundersen P (2002) Change in soil organic carbon following afforestation of former arable land. For Ecol Manag 169:137–147

Vesterdal L, Clarke N, Sigurdsson BD, Gundersen P (2013) Do tree species influence soil carbon stocks in temperate and boreal forests? For Ecol Manag 309:4–18

Wang Q, Wanga S, Zhang J (2009) Assessing the effects of vegetation types on carbon storage fifteen years after reforestation on a Chinese fir site. For Ecol Manag 258:1437–1441

Weiskittel AR, MacFarlane DW, Radtke PJ, Affleck DLR, Temesgen H, Woodall CW, Westfall JA, Coulston JW (2015) A call to improve methods for estimating tree biomass for regional and national assessments. J For 113:414–424

Wilson JB (1988) Shoot competition and root competition. J Appl Ecol 25:279–296

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Llinos Hughes and Mark Hughes of Henfaes Research Centre, Bangor University, for their help in harvesting the trees and sampling and processing the soils.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Natural Resources and Life Sciences Vienna (BOKU). The experimental facility and establishment of the plantation were supported by the INTERREG IVB North-West Europe project 003A ForeStClim. IUA was supported both by ForeStClim and the Forestry Commission UK for part of the work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Declaration of conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Handling editor: Andreas Bolte

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contribution of the co-authors

Iftekhar U. Ahmed: Carried out the field and laboratory activities, data analysis and drafted the manuscript.

Andrew R. Smith: Design of the experiments, supervising the sampling and laboratory analyses.

Douglas L. Godbold: Conceived the idea and approach, field activities, modification of the manuscript and overall supervision.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Allometric relationship between plant variables and woody biomass (WB) of B. pendula, A. glutinosa and F. sylvatica. Scattered plots show data from ten selected plants and the best fitted lines with basal diameter for B. pendula and F. sylvatica and diameter at breast height (DBH) for A. glutinosa. The regression equations, coefficient of determination and P values (using ANOVA) are inserted in each panel

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Appendix 4

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ahmed, I.U., Smith, A.R. & Godbold, D.L. Polyculture affects biomass production of component species but not total standing biomass and soil carbon stocks in a temperate forest plantation. Annals of Forest Science 76, 91 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-019-0875-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-019-0875-2