Abstract

Ferulate-5-hydroxylase (F5H) is a key rate-limiting enzyme for the conversion of guaiacyl monolignol (G-monolignol) to syringyl monolignol (S-monolignol) in the specific synthetic lignin pathway, through the catalysis of the 5-hydroxylation of S-monolignol precursors ferulic acid, conifer aldehyde, and coniferyl alcohol. In this study, we cloned the F5H gene of Populus tomenta (PtoF5H), whose product has a highly conserved domain of P450-dependent monooxygenase family. Subcellular localization result demonstrated that PtoF5H protein is an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) resident protein. Furthermore, the PtoF5H was transformed into tobacco in the form of sense- and antisense-, showed that the proportion of S-monolignol increased when PtoF5H gene was overexpressed, suggesting PtoF5H could be used as a target gene for modifying lignin composition. These findings provide further insight into the function of PtoF5H.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lignin is an aromatic polymer that widely exists in the secondary cell wall of vascular plants. It is an integral component of plant cells (Ralph et al. 2004), especially in woody plant species (Kai et al. 2016), and it plays a key role in maintaining the structural integrity of plant cell walls as well as the strength of stem. The polymer also transports water and inorganic salts through the plant catheter system to ensure normal plant growth is maintained (Coleman et al. 2008). Furthermore, lignin assists plants in resisting external stressors (abiotic and biotic) (Vanholme et al. 2010) and helps protect polysaccharides in the plant cell wall from degradation by exogenous microorganisms.

Despite lignin play an important role in the normal physiology of plants, the polymer interferes with the use of biomass by humans, meanwhile the interactions between lignin and cell polysaccharides greatly impede the conversion of these polymers for industrial and agricultural purposes (Kim et al. 2015; Weng et al. 2008). To overcome this challenge, many strategies to reduce lignin content or alter lignin composition and structure have been implemented with the overall goal of increasing cell wall degradability (Anderson et al. 2015), in this process, plant genetic engineering provides the opportunity to improve the structure and composition of plant secondary cell walls.

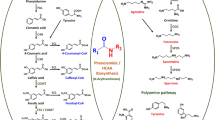

The lignin macromolecule is mainly composed of three monomers, p-hydroxyphenyl lignin (H-monolignol), guaiacyl lignin (G-monolignol) and syringyl lignin (S-monolignol), all of which are derived from phenylalanine (Ralph et al. 2004). F5H (ferulate-5-hydroxylase) is a key rate-limiting enzyme for the conversion of G-monolignol to S-monolignol (Huang et al. 2009), and the subsequent synthesis of S-monolignol precursor through the catalyzation of 5—hydroxylation of coniferaldehyde and coniferyl alcohol (Humphreys et al. 1999; Meyer et al. 1996, 1998). F5H gene was down-regulated in rapeseed and the content of sinapic acid choline decreased by 40–90% (Bhinu et al. 2009; Nair et al. 2000). Sinapic acid choline is a derivative of sinapic acid, implying that down-regulated F5H gene reduced the content of sinapic acid. In jute, the expression of F5H and coumarate 3-hydroxylase genes were down-regulated by transgenic engineering, showed that the content of lignin and cellulose decreased by 25% and 12–15% respectively (Shafrin et al. 2015). Therefore, it can be speculated that the heterotopic overexpression of F5H gene may greatly affect the plant lignin monomer composition. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the PtoF5H gene could be used as a target for modifying lignin composition (Armin et al. 2015; Shafrin et al. 2015).

In order to understand the enzymatic activity of PtoF5H more clearly, the gene was cloned and analyzed by bioinformatics. The protein extends it mainly protein folds to the cytoplasm by predicting, comparing other F5H structure and characteristics of P450 families. Meanwhile, subcellular localization result demonstrated that PtoF5H is an ER (endoplasmic reticulum) membrane protein, which accord with the other P450 family members. When sense- and antisense- vectors were constructed and transformed into tobacco to analyze the changes of the lignin content ratio, GC–MS (Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometer) analysis suggested that F5H affected the lignin G/S ratio.

Materials and methods

Gene cloning of Populus tomentosa F5H gene

Stem differentiating xylem (SDX) used for cloning was harvested from P. tomentosa 741 strains growing in Shenzhou, Hebei. Samples collected were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at − 80 °C until used. Extraction of RNA was operated from SDX using to the Plant RNA Extraction Kit (AidLab, China). Quality was checked by both electrophoresis and biomate 3S UV–Visible spectrophotometer. CDNA was synthesized after DNase digestion with the cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (AidLab, China). Genome-wide screening of PtoF5H had been performed based on Populus trichocarpa genome. PCR primers were designed based on P. trichocarpa genome for cloning genes. The full-length cDNA sequence of PtoF5H was cloned using forward 5′-GTCCCAATGGATTCTCTCAAT-3′ and reverse 5′-TCCCGGGTTAAAGTGGACACGACC-3′ primers. PCR products were purified by Quick Gel Extration Kit (AidLab, China) and cloned into the pMD18-T vector (Takara, Japan), propagated in E.coli Jm109 and inserts were confirmed by sequencing. Sequences were deposited at GenBank (accession number: KX227460.1). VectorNTI 11.5 was used to analyze open reading frame of the sequence.

Phylogenetic tree and alignment

The nucleotide sequence and deduced amino acid sequence were analyzed by BLASTn and BLASTp on NCBI database respectively. The protein sequence of PtoF5H was analyzed by using the physico-chemical parameters of a protein sequence in ExPASy database (https://expasy.org/tools/protparam.html). SignalP 4.1 (https://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) was used to predict the PtoF5H signal peptide sequence, and TMHMM Server v.2.0 (https://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/) was used to predict the transmembrane region. F5H amino acid sequences of different species were searched by NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The complete amino acid sequences of 10 species were selected, including Populus trichocarpa (ACC63881), Populus euphratica (XP_011025901), Liquidambar formosana (AAD48912.1), Hibiscus japonica (AGJ84132.1), Brassica napus (ABG73616.1), Arabidopsis thaliana (NP_195345.1), Solanum lycopersicum x Solanum peruvianum (AAD37433.1), Caragana korshinski (AEV93477.1), Medicago truncatula (XP_003629360), Saccharum hybrid cultivar (AOR81843.1), and were analyzed by multiple sequence alignment using DNAMAN, while other plant sequences homologous to PtoF5H were searched by using BLASTp function in NCBI database. We constructed a neighbour-joining tree based on a Clustal W amino acid alignment generated with the Mega 6.0 software (https://www.megasoftware.net/) with the following parameters: Poisson correction, complete deletion and bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates.

Microarray chip assays

The root, bud, xylem and phloem of P. tomentosa were collected in spring, summer, autumn and winter, the samples were quickly stored in liquid nitrogen and then stored at − 80 °C. Three biological replicates were set for each sample. RNA extraction and chip experiments of samples were completed by CapitaBio Corporcation. The chip was GeneChip Poplar Genome Array by Affymetrix and it contain over 60,000 probes which was designed basis with UniGene Build and mRNAs and ESTs of all Populus species in GenBank and 45,555 gene models predicted by JGI. Finally, forty-eight gene chips were obtained specifically for P. tomentosa. Subsequently, hybridization signals were collected using a chip detection system. The signal intensity represented the transcription level. The expression spectrum data were annotated by Molecule Annotation System V4.0, and the PtoF5H probe was detected by local Blast and E value < 10E−10.

Gene constructs

This study use pBI121 as the plant expression vector to construct sense PtoF5H and anti-sense PtoF5H vectors, named pBI-Sense-F5H and pBI-Antisense-F5H, respectively. These two vectors were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 and then infected into tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) with the leaf dish transformation (Horsch et al. 1989), for analysis the function of PtoF5H. GFP (Green fluorescence protein) coupling vector pBI121-F5H-GFP (F5H::GFP) and pBI121-GFP (Free GFP) were constructed and transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 for observing the subcellular localization of PtoF5H, when the cell was propagated to OD value of 0.4–0.6, and the cell was centrifuged to precipitate and suspended in the suspension buffer, then were infltrated into N.Benthamiana.

Tobacco treatment and identification of positive transgenic plants

After 2–4 weeks, seedlings of aseptic tobacco which could grow normally in 1/2 MS selective medium containing antibiotics were selected by 50 mg/L kanamycin. Total DNA was extracted from one of the tobacco seedlings by CTAB method for PCR and southern blot screening. The quantification of mRNA expression about the transgenic tobacco was identified by semi-quantitative PCR, using tobacco housekeeping gene (beta-actin) as internal reference standard, forward primer and reverse primer were designed separately. Meanwhile the specific primers were designed to analyze the semi-quantitative expression of transgenic tobacco (pBI-Sense-F5H and pBI-Antisense-F5H) with PtoF5H gene as target fragment.

The identified transgenic positive plants (pBI-Sense-F5H and pBI-Antisense-F5H) and a wild type plants were transplanted to the soil and cultivated indoors. Cell wall components were extracted from the fifth to thirteenth internodes of transgenic tobacco which was first generation and had been transplanted indoors for three months. The positive strains (pBI121-F5H-GFP and pBI121-GFP) were used to observe the subcellular localization.

Analysis of lignin composition in transgenic tobacco

The lignin composition and S/G ratio of transgenic tobacco and wild type tobacco (as a control sample) were analyzed. The method for lignin analysis was as described previously, the G/S/H monolignols were decomposed by thioacidolysis and were analyzed by GC–MS with ampere + capillary improvement (Tian et al. 2013). Each sample (cell wall components solution) was replicated three times to obtain average value.

Protoplast preparation and confocal SP8 microscopy observation

The protoplasts were prepared from the leaves of 4-week-old transgenic tobacco which were cultivated at 20–25 °C with 16 h light and 8 h dark per day, by using protoplast enzymatic hydrolysate, which contain 2 mM MES, 154 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 125 mM CaCl2, 0.5% BSA (w/v), 1% cellulase (w/v) and 0.25% pectinase (w/v) (Bart et al. 2006). The enzymatic hydrolysate was placed in a 100 rpm shaker for 1–2 h. After enzymatic hydrolysis, the turbid sediments in the middle and lower layers of the suction tube were placed at room temperature for 5 min. ER-marker was added to the centrifugal tube at the ratio of 1:2000, and the fluorescence was observed by confocal SP8 under room temperature staining for 5 min. ER-marker was red fluorescence. The maximum excitation wavelength of ER marker was 587 nm and the maximum emission wavelength was 615 nm.

Results and discussion

Characteristics of PtoF5H

F5H gene was obtained from P.tomentosa. The complete open reading frame is 1542 bp. ProParam (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) predicted that the PtoF5H encoded 513 amino acids with a relative molecular weight of 58.31 kDa. The predicted result of TargetIP (https://targetip.neilroger.co.uk/) showed that the PtoF5H contained a signal peptide. TMHMM (https://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/) transmembrane analysis revealed that there was a single transmembrane structure in the amino acid sequence of the N- terminal 7–29 amino acids.

Multiple sequences alignment and Phylogenetic analysis of PtoF5H and PtoF5H-like proteins

We found that PtoF5H has the same highly conserved sequence as that of other cytochrome P450 monoxidase family members by phylogenetic analysis (Figs. 1, 2), including the transmembrane region in N-terminal that binding to the ER membrane. The presumed positive charge termination transfer signal sequence (RLRRR, 31–35) is adjacent to this region with a conserved proline-rich sequence (PPGP) and a C-terminal cysteine heme-bound sequence (PFGSGRRSCPG), which is a highly conserved element, commonly used to identify the P450 members. The PtoF5H was homologous to P. trichocarpa (ACC63881), P. euphratica (XP_011025901), L. formosana (AAD48912.1), H. japonica (AGJ84132), E. rape (ABG73616.1), A. thaliana (NP_195345.1), S. lycopersicum x S. peruvianum (AAD37433.1), C. korshinski (AEV93477.1), M. truncatula (XP_0036360), S. hybrid cultivar (AOR81843.1), which was 92.94%, 85.87%, 74.35%, 73.98%, 72.12%, 71.00%, 70.63%, 70.07%, 67.47% and 61.90%, respectively. The similarity of the sequence homology indicated that the structure of PtoF5H is consistent with that of P.trichocarpa F5H, further demonstrating that the cloned sequence is genuine F5H.

Phylogenic tree of F5H orthologs. The following F5H sequences were used: Populus trichocarpa (ACC63881), Populus tomentosa (APX43202.1), Populus trichocarpa (CAB65335), Populus euphratica (XP_011028697), Populus euphratica (XP_011025901), Garcinia mangostana (AID69231), Hibiscus cannabinus (AGJ84132), Acacia koa (AOX49218), Caragana korshinski (AEV93477), Medicago truncatula (XP_003629360), Eucalyptus globules (ACU45738), Arabidopsis thaliana(NP_195345), Brassica napus (ABG73616), Liquidambar styraciflua (AF139532_1), Trapabicornis (ALC76578), Broussonetia papyrifera (AAW50817), Morusnotabilis (AGT57171), Pyrus bretschneideri (AGR44939), Camptotheca acuminata (AAT39511), Lycopersicon esculentum x Lycopersicon peruvianum (AF150881_1), Angelica sinensis (AJW77400), Daucuscarota (ANF06870), Chrysanthemum x morifolium (BAM66576), Panicum virgatum (BAO37287), Miscanthus x giganteus (ANB43568), Saccharum hybrid cultivar (AOR81843)

Spatiotemporal expression analysis of PtoF5H

Mining data in microarry chip, the average expression level of PtoF5H in root, bud, xylem cambium, and phloem cambium was obtained for each of the four seasons in a year. The result revealed that the expression level of PtoF5H in the root, xylem, and phloem were not significantly different throughout the year, but the expression level of bud was lower in winter than that of other seasons (Fig. 3). The expression profiles of PtoF5H are similar to Brassica napus F5Hs, however high expression of B. napus F5H2 was found in young stem (Nair et al. 2000), while the highest expression of PtoF5H was found in root and bud, presumably due to the presence of other F5H in P. tomentosa. The low expression of PtoF5H in bud during the winter may lead to the accumulation of lignin synthesis precursors in the phenylpropane pathway, similar to the accumulation of sinapic acid, ferulic acid, and coumaric acid in rape seed after low temperature treatment (Solecka et al. 1999).

Expression level of PtoF5H in specific organ or tissue in a year. Bud, root, xylem and phloem are presented with black and white, gray (dark black: bud, gray root, dark gray: xylem, light, gray: phloem). Signal intensity is statistically tested and variations are indicated by bars. Different letters on the top mean significant difference exist among the statistics according to Turkey’s HSD test; (P < 0.05)

The previous study reported that P.trichocarpa cinnamic acid 4-hydroxylase was also found in P450 members of the phenylpropane pathway and it have high expression level in the xylem (Ro et al. 2001). However, the expression of F5H in root of P. tomentosa maintained a high level throughout the entire year and the expression level in phloem and xylem was significantly lower than in root and bud. We speculate that the downstream products of PtoF5H are not only involved in lignin synthesis (Chapple et al. 1992), but also in the synthesis of secondary metabolites such as flavonoids. These secondary metabolites are related to plant defense against ultraviolet tradition, as well as abiotic stress and disease resistance (Kim et al. 2006; Liu et al. 2015). It has been reported that the F5H and Sinapoylglucose: choline sinapoyltransferase (SCT) mutants of Arabidopsis are more susceptible to disease infection than wild type lines (Huang et al. 2009). Since the expression of PtoF5H in P. tomentosa bud was the lowest in winter.

Subcellular localization of PtoF5H

Experimental verification by confocal SP8 microscopy showed the green fluorescence of the protoplast of pBI121-GFP vector (control) expression through out of the cell (Fig. 4a) and red fluorescence was shown by ER Tracker staining (Fig. 4b). The picture (Fig. 4c) revealed that it is not completely overlap. In transformed tobacco leaf epidermal cells, transiently expressed pBI121-F5H-GFP (Fig. 4e) and red fluorescence (Fig. 4f) were completely overlap in the image (Fig. 4g). It indicated that PtoF5H was localized in the ER of tobacco leaf cells, which is consistent with the location results of CAld5H1 and CAld5H2 of P.trichocarpa (Wang et al. 2012).

Subcellular localization of GFP and PtoF5H-GFP fusion protein expressed in tobacco leaf epidermal cells. Representative confocal images show pBI121-PtoF5H-GFP expressed in tobacco leaf epidermal cells by agroinfiltration. a GFP control; b, f ER-tracker; e pBI121-PtoF5H-GFP; c, g a and b overlap, e and f overlap; respectively; d, h C and G in bright field

Analysis of the ratio of G- and S-monolignol in transgenic tobacco

The two sense positive lines were named S1 and S3, and the two antisense positive lines were named A1 and A12. We found that transgenic plants had different expression patterns compared with the wild type when the tobacco housekeeping gene (beta-actin) keeped the same brightness. In sense lines, the expression of PtoF5H increased significantly, and in antisense lines, expression decreased slightly. The content of lignin monomers of transgenic tobaccos was in Table 1. The result about the ratio of lignin monomer G/S between wild type and transgenic tobacco showed that overexpression of PtoF5H in tobacco brought a decreased G/S ratio (Fig. 5). However, the ratio of G/S monolignol did not change significantly in the antisense positive tobacco. The total content of G- and S-monolignol in wild-type tobacco was regarded as 100%.

This result indicated that PtoF5H regulated the conversion of G-monolignol to S-monolignol in the specific pathway of lignin synthesis. However, the antisense PtoF5H inhibition of F5H expression in tobacco did not reduce the proportion of S-monolignol, the result of tobacco genome sequencing suggest that there might be more than one F5H in tobacco genome. It was also reported that two F5H in P. tomentosa genome were functionally redundant (Wang et al. 2012). Furthermore, because of the low homology between F5H in tobacco and F5H in P. tomentosa, good silencing effect was not achieved. The specific reasons need to be further verified.

Abbreviations

- ER:

-

Endoplasmic reticulum

- F5H:

-

Ferulate-5-Hydroxylase

- GC–MS:

-

Gas chromatography–mass spectrometer

- GFP:

-

Green fluorescence protein

References

Armin W, Yuki T, Lorelle P, Heather F, Barbara G, Fachuang L, John R (2015) Syringyl lignin production in conifers: Proof of concept in a Pine tracheary element system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112:6218–6223. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1411926112

Bart R, Chern M, Park CJ, Bartley L, Ronald PC (2006) A novel system for gene silencing using sirnas in rice leaf and stem-derived protoplasts. Plant Methods 2:13–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4811-2-13

Bhinu VS, Schäfer UA, Li R, Huang J, Hannoufa A (2009) Targeted modulation of sinapine biosynthesis pathway for seed quality improvement in Brassica napus. Transgenic Res 18:31–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11248-008-9194-3

Chapple CC, Vogt T, Ellis BE, Somerville CR (1992) An Arabidopsis mutant defective in the general phenylpropanoid pathway. Plant Cell 4:1413–1424. https://doi.org/10.2307/3869512

Coleman H, Samuels A, Guy R, Mansfield S (2008) Perturbed lignification impacts tree growth in hybrid poplar-a function of sink strength, vascular integrity, and photosynthetic assimilation. Plant Physiol 148:1229–1237. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.108.125500

Horsch RB, Fry J, Hoffmann N, Neidermeyer J, Rogers SG, Fraley RT (1989) Leaf disc transformation. Plant Mol Biol Manual A5:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-0951-9_5

Huang J, Bhinu VS, Li X, Bashi ZD, Zhou R, Hannoufa A (2009) Pleiotropic changes in Arabidopsis f5h and sct mutants revealed by large-scale gene expression and metabolite analysis. Planta 230:1057–1069. https://doi.org/10.2307/23390769

Humphreys JM, Hemm MR, Chapple C (1999) New routes for lignin biosynthesis defined by biochemical characterization of recombinant ferulate 5-hydroxylase, a multifunctional cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:10045–10050. https://doi.org/10.2307/48691

Kai D, Tan MJ, Chee PL, Chua YK, Yap YL, Loh XJ (2016) ChemInform abstract: towards lignin-based functional materials in a sustainable world. Cheminform 47:1175–1200. https://doi.org/10.1002/chin.201615279

Kim Y, Kim D, Lee S (2006) Wound-induced expression of the ferulate 5-hydroxylase gene in Camptotheca acuminata. Biochim Biophys Acta 1760:182–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbagen.2005.08.015

Kim Y, Kreke T, Ko JK, Ladisch MR (2015) Hydrolysis-determining substrate characteristics in liquid hot water pretreated hardwood. Biotechnol Bioeng 112:677–687. https://doi.org/10.1002/bit.25465

Liu Q, Zheng L, He F, Zhao FJ, Shen Z, Zheng L (2015) Transcriptional and physiological analyses identify a regulatory role for hydrogen peroxide in the lignin biosynthesis of copper-stressed rice roots. Plant Soil 387:323–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-014-2290-7

Meyer K, Cusumano JC, Somerville C, Chapple CC (1996) Ferulate-5-hydroxylase from Arabidopsis thaliana defines a new family of cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 93:6869–6874. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.93.14.6869

Meyer K, Shirley AM, Cusumano JC, Bell-Lelong DA, Chapple C (1998) Lignin monomer composition is determined by the expression of a cytochrome P450-dependent monooxygenase in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:6619–6623. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.95.12.6619

Nair RB, Joy RW, Kurylo E, Shi X, Schnaider J, Datla RS, Keller WA, Selvaraj G (2000) Identification of a CYP84 family of cytochrome P450-dependent mono-oxygenase genes in Brassica napus and perturbation of their expression for engineering sinapine reduction in the seeds. Plant Physiol 123:1623–1634. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.123.4.1623

Ralph J, Lundquist K, Brunow G, Lu F, Kim H, Schatz PF, Marita JM, Hatfield RD, Ralph SA, Christensen JH (2004) Lignins: natural polymers from oxidative coupling of 4-hydroxyphenyl-propanoids. Phytochem Rev 3:29–60. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:PHYT.0000047809.65444.a4

Ro DK, Mah N, Ellis BE, Douglas CJ (2001) Functional characterization and subcellular localization of poplar (Populus trichocarpa x Populus deltoides) cinnamate 4-hydroxylase. Plant Physiol 126:317–329. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/43.4.442

Shafrin F, Das SS, Sanan-Mishra N, Khan H (2015) Artificial miRNA-mediated down-regulation of two monolignoid biosynthetic genes (C3H and F5H) cause reduction in lignin content in jute. Plant Mol Biol 89:511–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-015-0385-z

Solecka D, Boudet AM, Kacperska A (1999) Phenylpropanoid and anthocyanin changes in low-temperature treated winter oilseed rape leaves. Plant Physiol Biochem 37:491–496. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0981-9428(99)80054-0

Tian X, Xie J, Zhao Y, Lu H, Liu S, Qu L, Li J, Gai Y, Jiang X (2013) Sense-, antisense- and RNAi-4CL1 regulate soluble phenolic acids, cell wall components and growth in transgenic Populus tomentosa Carr. Plant Physiol Biochem 65:111–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2013.01.010

Vanholme R, Demedts B, Morreel K, Ralph J, Boerjan W (2010) Lignin biosynthesis and structure. Plant Physiol 153:895–905. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.110.155119

Wang JP, Li Q, Song J, Lin YC, Sun YH, Chen HC, Williams CM, Muddiman DC, Sederoff RR, Chiang VL (2012) Functional redundancy of the two 5-hydroxylases in monolignol biosynthesis of Populus trichocarpa: LC–MS/MS based protein quantification and metabolic flux analysis. Planta 236:795–808. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-012-1663-5

Weng JK, Li X, Bonawitz ND, Chapple C (2008) Emerging strategies of lignin engineering and degradation for cellulosic biofuel production. Curr Opin Biotechnol 19:166–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2008.02.014c

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation [NSF 31300498 to Y.G.].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XJ and YG designed and supervised the study; QZ and YJ performed the experiments; WJ analyzed the data and prepared the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jiang, W., Zeng, Q., Jiang, Y. et al. Molecular and functional characterization of ferulate-5-hydroxylase in Populus tomentosa. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 30, 92–98 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13562-020-00574-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13562-020-00574-9