Abstract

Introduction

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease with different phenotypes. There is accumulating evidence that the commensal Demodex mite is linked to papulopustular rosacea. Established treatment options, including topical metronidazole, azelaic acid, and tetracyclines, are thought to work through their anti-inflammatory effects. However, none of these therapies have been shown to be curative and are associated with frequent relapses. Therefore, new and improved treatment options are needed. Topical ivermectin 1.0% cream is a new option having both anti-inflammatory and acaricidal activity against Demodex mites which might pave the way to a more etiologic approach. Its use has now been widely adopted by clinical guidelines. The objective was to review the evidence and clinical guideline recommendations concerning ivermectin 1.0% cream in the treatment of papulopustular rosacea.

Methods

A systematic review of both medical literature and clinical guideline recommendations was conducted. Numbers needed to treat (NNT) were calculated for relevant dichotomous outcomes (e.g., relapse rate and achieving full lesion clearance) to compare ivermectin with other established treatment options for rosacea.

Results

The search identified three randomized trials, three extension studies, and two meta-analyses. Ivermectin has only been tested in moderate-to-severe papulopustular rosacea. Ivermectin is an effective treatment option for papulopustular rosacea and seems to be more effective than metronidazole (NNT = 10.5) at 12 weeks of treatment. Although ivermectin was numerically more effective than metronidazole at week 36 in preventing relapse (NNT = 17.5), relapse after discontinuation of treatment in both groups was common with 62.7% and 68.4% of patients relapsing. Based on limited generalizability of available evidence, clinical guidelines have yielded different treatment algorithms and, in some areas, conflicting recommendations.

Conclusion

Topical ivermectin is an effective option in the treatment of papulopustular rosacea. Although ivermectin seems to be more effective than topical metronidazole, with both treatment options about two-thirds of patient relapsed within 36 weeks after discontinuation of treatment. More research is needed to establish the clinical benefit of ivermectin’s acaricidal action in preventing relapse compared to other non-etiologic treatment approaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease affecting primarily the cheeks, nose, chin, and forehead [1]. It has been generally classified into four clinical subtypes, of which the erythematotelangiectatic subtype is most common followed by the papulopustular subtype [28, 30, 31]. Since subtypes frequently overlap and can vary over time, a phenotype approach is now recommended by an international ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel, the National Rosacea Society, and the American Acne and Rosacea Society in recognition of the inaccuracies and limitations of subtyping [29]. The prevalence of rosacea varies greatly between countries and has been reported to range from less than 1% to 22% [28]. Most frequently, women between 30 and 50 years of age are affected, although rosacea is also common among men [8]. Rosacea can negatively affect both social and professional life and is linked to depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem [3, 7, 12, 16]. Although the pathophysiology of papulopustular rosacea is not fully understood, the first experimental study in vivo demonstrated a potentially important role for Demodex folliculorum [21]. Although these mites are part of the normal cutaneous microflora, it has been shown that the cutaneous density of Demodex mites in patients with rosacea is increased [9,10,11, 32]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that Demodex mites have the capacity to downregulate the Toll-like receptor-2 (TLR-2) response to facilitate their survival [15]. In contrast, when present in increased numbers, Demodex mites activate a TLR-2 pathway immune response. This results in the release of pro-inflammatory mediators leading to inflammatory skin changes [13, 15]. Established treatment options, including topical metronidazole, azelaic acid, and tetracyclines, are thought to work through their anti-inflammatory but not through their antimicrobial effects. However, none of these therapies have been shown to be curative and are associated with frequent relapses, even during treatment [35]. Therefore, new and improved treatment options are needed. Ivermectin was originally used as an oral anti-parasitic drug and has a dual mechanism of action, having both anti-inflammatory and acaricidal activity against Demodex mites [14, 21]. Thus, topical ivermectin might pave the way to a more etiologic treatment of papulopustular rosacea with less frequent relapses. Thus, its use is now widely propagated in mild-to-severe papulopustular rosacea [21, 22]. However, current clinical guidelines have yielded different treatment algorithms and, in some areas, conflicting recommendations [2, 22, 1]. The objective of this systematic review is to critically appraise current evidence and guideline recommendations for the use of topical ivermectin in papulopustular rosacea.

Methods

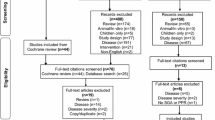

Two authors independently conducted a MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PUBMED search of articles in English published from 1980 to February 2018 using the terms “rosacea” and “ivermectin” or “guideline” to identify controlled, randomized, and non-randomized clinical trials, meta-analyses, and clinical guidelines. Non-controlled trials were excluded. We also reviewed the reference lists of selected articles. Primarily, we searched for the following relevant outcomes: absolute change in inflammatory lesion count compared to baseline, physician-assessed outcomes, and serious adverse events. Secondary, we reviewed patient-assessed outcomes and quality of life. Risk of bias was independently assessed by two authors for all included studies using the Oxford quality scoring system (Jadad score). Any inconsistencies in ratings were resolved by input from a third author. When not reported, we calculated numbers needed to treat (NNT) for applicable outcomes (Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) score, patient-assessed outcomes, and relapse rates). This review is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Results

In total 76 potential hits were found, but only three controlled clinical trials, two continuation studies, and two meta-analyses were identified [23, 24, 26, 27, 33, 34]. All clinical studies were sponsored by Galderma, which holds ivermectin 1.0% in its product portfolio. Short-term efficacy of topical ivermectin in the treatment of papulopustular rosacea was evaluated in two, simultaneously reported, double-blind, randomized phase III trials versus vehicle [34] and in one investigator-blinded trial versus topical metronidazole [27]. Eligibility criteria included an inflammatory facial lesion count of 15–70 and an IGA score ≥ 3, indicating moderate-to-severe papulopustular rosacea (Table 1). Patients were mainly Caucasian (> 95%), had a mean age of 50–52 years, and a mean inflammatory lesion count of 31–33. Most patients had moderate rosacea (76–83%) and the remaining patients had severe rosacea (17–24%). The primary outcome in all three trials was the change from baseline in inflammatory lesions count (papules and/or pustules). Secondary outcomes were investigator-assessed improvement in rosacea severity, as measured by IGA score, patient-assessed improvement in rosacea severity, measured on a global 5-point scale (worse, no improvement, moderate, good, or excellent) and quality of life, as measured by the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) questionnaire. Safety assessment included adverse events and local tolerance (stinging/burning, dryness, itching) evaluated on a 4-point scale (0 being absent to 3 being severe).

Ivermectin Versus Vehicle

Two simultaneously reported randomized trials compared once-daily ivermectin 1.0% cream (study 1 n = 451 and study 2 n = 459, respectively) with vehicle (n = 232 and n = 229, respectively) during a period of 12 weeks [34]. In both trials, a statistically significant difference was found in inflammatory lesion counts in favor of ivermectin. The change in mean difference from baseline to 12 weeks between ivermectin and vehicle was − 8.13 and − 8.22 lesions, in study 1 and study 2, respectively. Ivermectin was also significantly more effective than control in achieving IGA scores ≤ 1 (clear/almost clear) at 12 weeks (38.4% vs. 11.6% and 40.1% vs. 18.8%, NNT = 3.7 and NNT = 4.7, respectively). Statistically significant differences in IGA scores between ivermectin and vehicle were first reached after 4 weeks of treatment. Patient-assessed outcomes were significantly better in the ivermectin group, with more patients rating their rosacea improvement as “excellent” or “good” after 12 weeks in both trials (69.0% versus 38.6%, and 66.2% versus 34.4%, NNT = 3.3 and NNT = 3.1, respectively). No major safety issues were observed and side effects were mild.

After 12 weeks, both trials were extended for 40 weeks in an investigator-blinded design [24]. Patients originally receiving ivermectin 1.0% were given the option to continue ivermectin or withdraw. Control patients were switched to azelaic acid 15% gel twice daily. A total of 412 and 428 patients were enrolled in the ivermectin group and 210 and 208 were enrolled in the azelaic acid group, respectively [24]. After 40 weeks of continued treatment, 71.1% and 76.0% of ivermectin recipients had an IGA score ≤ 1 in study 1 and study 2, respectively, as compared to 59.4% and 57.9% of azelaic 15% gel recipients. This corresponds to an NNT of 8.5 in study 1 and an NNT of 5.5 in study 2.

A Cochrane review based on the two previously mentioned clinical trials found participant-assessed improvement in rosacea severity to be significantly better for ivermectin versus placebo [relative risk [RR] 1.78, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.50–2.11 and RR 1.92, 95% CI 1.59–2.32] [33]. Physician-assessed improvement in rosacea severity was also significantly better for ivermectin versus placebo (RR 3.30, 95% CI 2.27–4.79 and RR 2.10, 95% CI 1.57–2.81). The mean difference in lesion count was − 8.40 and − 8.90, respectively, in favor of ivermectin. There were no differences in adverse effects (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.29–1.01 and RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.55–1.82) [33].

Ivermectin Versus Metronidazole

A single investigator-blinded, randomized trial compared topical ivermectin 1.0% cream once daily (n = 478) with topical metronidazole 0.75% cream twice daily (n = 484) [27]. Measured as percentage change from baseline, ivermectin reduced the inflammatory lesion count to a significantly higher extent than metronidazole at 16 weeks of treatment (83.0% versus 73.7%). Ivermectin was also significantly more effective than metronidazole in achieving IGA scores ≤ 1 (84.9% vs. 75.4%, NNT = 10.5). An IGA score of 0 was achieved in 34.9% of ivermectin recipients vs. 21.7% of metronidazole recipients (NNT = 7.6). Patient-assessed outcomes were significantly better in the ivermectin group, with more patients rating their rosacea improvement as “excellent” or “good” (85.5% vs. 74.8%, NNT = 9.3).

Patients who achieved IGA scores ≤ 1 were allowed to enter a 36-week extension study. For all patients, study medication was discontinued to evaluate time to first relapse [26]. The extension study was investigator-blinded with investigators and patients not allowed to discuss study treatments. In total, 762 patients met these criteria, with 757 patients deciding to continue (399 patients using ivermectin and 358 patients using metronidazole). Relapse was defined as an IGA score ≥ 2. The primary efficacy outcome was time to first relapse, defined as the time between week 16 and the first relapse during the 36-week extension period. Relapse rate was defined as the percentage of patients who relapsed within the course of the 36-week extension study. The median time to first relapse was higher for ivermectin compared to metronidazole (115 days, 95% CI 113–165 days versus 85 days, 95% CI 85–113 days). At 36 weeks, 62.7% of patients using ivermectin had a relapse versus 68.4% of metronidazole recipients (log-rank test, p = 0.037, NNT = 17.5). No major safety issues were observed.

A network meta-analysis using Bayesian methodology based on both published and unpublished data compared ivermectin with other treatment options. The success rate was defined as either an IGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (minimal) on a 5-point scale, or 0 (clear), 1 (minimal), or 2 (mild) on a 7-point Likert scale. Ivermectin showed a significantly greater likelihood of success compared with azelaic acid 15% gel twice-daily (RR 1.25, 95% CI 1.14–1.37) and metronidazole 0.75% cream twice-daily (RR 1.17, 95% CI 1.08–1.29) at 12 weeks [23]. Ivermectin 1% cream also demonstrated a significant reduction in inflammatory lesion count compared with azelaic acid 15% gel twice-daily (− 8.04, 95% CI − 12.69 to − 3.43) and metronidazole 0.75% cream twice-daily (− 9.92, 95% CI − 13.58 to − 6.35) at 12 weeks. Ivermectin 1.0% cream led to a significantly lower risk of developing any adverse effect compared with azelaic acid 15% (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.71–0.97 and 0.47, 95% CI 0.32–0.67, respectively).

Ivermectin in Clinical Guidelines

We found three clinical guidelines and one consensus update on the treatment of rosacea (Table 2) [1, 2, 19, 22]. In mild-to-moderate papulopustular rosacea, topical therapy with metronidazole, azelaic acid, or ivermectin is considered to be the first line of treatment. In moderate-to-severe papulopustular rosacea or rosacea inadequately responsive to topical treatment, systemic drug treatment is recommended, e.g., with tetracyclines or isotretinoin, often combined with topical treatment. Treatment algorithms were different for both mild-to-moderate and severe rosacea. Ivermectin was considered an effective option in three guidelines for mild papulopustular rosacea [1, 2, 22], but only in one guideline for severe papulopustular rosacea [22]. All guidelines recommend combination therapy with antibiotics and topical therapy in severe papulopustular rosacea. None of the guidelines preferred one topical agent over another.

Discussion

In this review, we aimed to provide an update on topical ivermectin in the treatment of rosacea compared to other treatment options. We calculated NNTs since these are highly informative for the practicing clinician. The NNT objectively compares treatments by indicating the number of patients that have to be treated with a new treatment option to obtain one extra favorable outcome or prevent one unfavorable outcome. Other reviews did not specifically focus on ivermectin [17, 25], did not include extension studies [33], did not review clinical guideline recommendations [4, 17, 25], or did not assess methodological quality and NNTs [4, 17, 25].

We found three randomized clinical trials with ivermectin, of which two compared ivermectin 1.0% cream with vehicle and one with metronidazole 0.75% cream. Ivermectin cream was more effective than vehicle and metronidazole in achieving IGA score ≤ 1 (NNT = 3.7–4.7 and NNT = 10.5, respectively). This means that 3.7–4.7 patients have to be treated with ivermectin instead of placebo to achieve this outcome and 10.5 patients with ivermectin instead of metronidazole. Overall, the three trials were of good methodological quality with a low risk of bias as measured by Jadad score, for the outcomes we primarily considered relevant (inflammatory lesion count and IGA score). Loss to follow-up was low in all studies. Patient-assessed outcomes were blinded in the trials comparing ivermectin with vehicle, but not in the trial comparing ivermectin with metronidazole. Therefore, this outcome carried a high risk of information bias, since patients knew which treatment they received and therefore might overestimate their treatment effect.

Following completion of all three randomized trials, extension phases were conducted. The three extension studies were only investigator-blinded, but patients and investigators were not allowed to discuss study treatment. It is unverifiable to what extent this protocol was respected and we consider these studies to be at high risk of information bias since they were single-blind. The extension study which evaluated time to relapse following discontinuation of ivermectin and metronidazole used an enriched design, by necessity only including patients who achieved a treatment effect of clear/almost clear. Since more patients achieved this outcome in the ivermectin arm, selection bias might at least partially explain this efficacy benefit. In the extension study which compared azelaic acid to ivermectin, the latter was more effective than azelaic acid (NNT = 5.5–8.5) in achieving IGA scores ≤ 1. However, this result should be interpreted with caution since treatment duration was longer with ivermectin as compared to azelaic acid (52 versus 40 weeks).

Accumulating evidence links overgrowth of the commensal Demodex mite to rosacea pathophysiology and recent studies suggest a strong correlation between treatment success and reduction in Demodex density [15, 18, 20, 21]. Ivermectin is thought to exhibit its effects in papulopustular rosacea through both anti-inflammatory and acaricidal actions against Demodex mites [21]. However, it cannot be ruled out that the anti-inflammatory effect of ivermectin is in fact due to its acaricidal action, thereby decreasing the innate immune system response to Demodex mites [21]. Topical metronidazole is thought to work solely by an anti-inflammatory action, but also decreases the follicular density of Demodex mites without directly killing them [20]. In the extension study versus metronidazole, ivermectin was slightly more effective at 36 weeks in preventing relapse (NNT = 17.5), though relapse rates after discontinuation of treatment in both groups were still 62.7% and 68.4% [26]. Given their distinct mechanism of action, one would have expected the difference in relapse rates to be more evident in favor of ivermectin. However, median time to first relapse was significantly longer for ivermectin compared to metronidazole (115 versus 85 days). A possible explanation might be different Demodex mite reproliferation rates after discontinuing treatment. If the central role of Demodex mites in rosacea pathophysiology can be confirmed, then ivermectin potentially is the most etiological treatment by avoiding new proliferation of mites. While parasitic resistance to ivermectin has been reported in nematodes after extensive veterinary use, this has not been reported for Demodex mites in rosacea and seems unlikely [5]. Although relapse with ivermectin might be less frequent compared with non-acaricidal treatments, the results of the extension study cannot be considered conclusive [26]. Therefore, this remains to be proven in a randomized controlled clinical trial.

Several other knowledge gaps remain. Ivermectin has only been tested in moderate-to-severe papulopustular rosacea in mainly Caucasian patients, consequently limiting the generalizability of the data. As such, the clinical benefit is possibly smaller in patients with mild papulopustular rosacea. A case series of 34 patients aimed to compare treatment effects of ivermectin cream in mild versus moderate-to-severe papulopustular and erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in clinical practice. Irrespective of its methodological limitations, it showed smaller clinical improvement in the mild patient group compared to the moderate-to-severe patient group [6]. Yet, clinical guidelines recommend topical therapy as first-line treatment only in patients with mild papulopustular rosacea. In moderate-to-severe papulopustular rosacea the current treatment standard is systemic drug therapy or combination therapy [1, 2]. In a rosacea treatment update, the global ROSCO panel also included topical ivermectin as a treatment option for severe papulopustular rosacea alongside oral doxycycline and isotretinoin [22]. However, ivermectin has not directly been compared to systemic therapy, and thus it is unknown which of these treatments is most effective. Although combining topical and systemic treatment may be beneficial in a select group of patients, the clinical benefit of adding ivermectin to systemic therapy currently remains unknown.

Despite these limitations, clinical guidelines have broadly adopted ivermectin in the treatment of papulopustular rosacea with varying treatment algorithms. Although propagated for mild rosacea and as topical agent in combination therapy, these recommendations are mainly consensus-based given the limited generalizability of current data. Additional research is required to establish the clinical benefit of topical ivermectin in patients with mild papulopustular rosacea, as a substitute for systemic therapy, and as an addition to oral treatment options.

Conclusions

Ivermectin 1.0% cream is an effective addition in the treatment of moderate-to-severe papulopustular rosacea and now adopted by clinical guidelines with varying treatment recommendations. Ivermectin is more effective than topical metronidazole, but relapse is still frequent for both treatment options with about two-thirds of patients relapsing after discontinuation of treatment. The potential benefit of the acaricidal action of ivermectin as a more etiological treatment option in papulopustular rosacea remains to be proven in a randomized clinical trial. After remission is achieved, we suggest to continue topical therapy given the high risk of relapse.

References

Anzengruber F, Czernielewski J, Conrad C, et al. Swiss S1 guideline for the treatment of rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31(11):1775–91.

Asai Y, Tan J, Baibergenova A, et al. Canadian clinical practice guidelines for rosacea. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20(5):432–45.

Bewley A, Fowler J, Schöfer H, Kerrouche N, Rives V. Erythema of rosacea impairs quality of life: results of a meta-analysis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2016;6:237–47.

Deeks ED. Ivermectin: a review in rosacea. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015;16:447–52.

Dourmishev AL, Dourmishev LA, Schwartz RA. Ivermectin: pharmacology and application in dermatology. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:981–8.

Mendieta Eckert M, Landa Gundin N. Treatment of rosacea with topical ivermectin cream: a series of 34 cases. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22(8).

Egeberg A, Hansen PR, Gislason GH, Thyssen JP. Patients with rosacea have increased risk of depression and anxiety disorders: a Danish nationwide cohort study. Dermatology. 2016;232:208–13.

Elewski BE, Draelos Z, Dréno B, Jansen T, Layton A, Picardo M. Rosacea–global diversity and optimized outcome: proposed international consensus from the Rosacea International Expert Group. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:188–200.

Forton FMN, De Maertelaer V. Two consecutive standardized skin surface biopsies: an improved sampling method to evaluate Demodex density as a diagnostic tool for rosacea and demodicosis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2017;97:242–8.

Forton F, Germaux MA, Brasseur T, et al. Demodicosis and rosacea: epidemiology and significance in daily dermatologic practice. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(1):74–87.

Forton F, Seys B. Density of Demodex folliculorum in rosacea: a case controlled study using standardised skin surface biopsy. Br J Dermatol. 1993;128:650–9.

Halioua B, Cribier B, Frey M, Tan J. Feelings of stigmatization in patients with rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:163–8.

Holmes AD, Steinhoff M. Integrative concepts of rosacea pathophysiology, clinical presentation and new therapeutics. Exp Dermatol. 2017;26:659–67.

Kircik LH, Del Rosso JQ, Layton AM, Schauber J. Over 25 years of clinical experience with ivermectin: an overview of safety for an increasing number of indications. J Drugs Dermatol. 2016;15:325–32.

Lacey N, Russell-Hallinan A, Zouboulis CC, Powell FC. Demodex mites modulate sebocyte immune reaction: possible role in the pathogenesis of rosacea. Br J Dermatol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjd.16540.

van der Linden MM, van Rappard DC, Daams JG, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with cutaneous rosacea: a systematic review. Acta Derm Venereol. 2015;95:395–400.

McGregor S, Alinia H, Snyder A, Tuchayi SM, Fleischer A, Feldman SR, A review of the current modalities for the treatment of papulopustular rosacea. Dermatol Clin. 2018;;36(2):135–150.

Raoufinejad K, Mansouri P, Rajabi M, et al. Efficacy and safety of permethrin 5% topical gel vs. placebo for rosacea: a double-blind randomized controlled clinical trial. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:2105–17.

Reinholz M, Tietze JK, Kilian K, et al. Rosacea–S1 guideline. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11(8):768–80 (768–79).

Sattler EC, Hoffmann VS, Ruzicka T, et al. Reflectance confocal microscopy for monitoring the density of Demodex mites in patients with rosa- cea before and after treatment. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:69–75.

Schaller M, Gonser L, Belge K, et al. Dual anti-inflammatory and antiparasitic action of topical ivermectin 1% in papulopustular rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:1907–11.

Schaller M, Almeida LM, Bewley A, et al. Rosacea treatment update: recommendations from the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:465–71.

Siddiqui K, Stein Gold L, Gill J. The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of ivermectin compared with current topical treatments for the inflammatory lesions of rosacea: a network meta-analysis. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):1151.

Stein Gold L, Kircik L, Fowler J, et al. Long-term safety of ivermectin 1% cream vs azelaic acid 15% gel in treating inflammatory lesions of rosacea: results of two 40-week controlled, investigator-blinded trials. J Drugs Dermatol. 2014;13:1380–6.

Steinhoff M, Vocanson M, Voegel JJ, Hacini-Rachinel F, Schäfer G. Topical ivermectin 10 mg/g and oral doxycycline 40 mg modified-release: current evidence on the complementary use of anti-inflammatory rosacea treatments. Adv Ther. 2016;33(9):1481–501.

Taieb A, Khemis A, Ruzicka T, et al. Maintenance of remission following successful treatment of papulopustular rosacea with ivermectin 1% cream vs. metronidazole 0.75% cream: 36-week extension of the ATTRACT randomized study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:829–36.

Taieb A, Ortonne JP, Ruzicka T, et al. Superiority of ivermectin 1% cream over metronidazole 0.75% cream in treating inflammatory lesions of rosacea: a randomized, investigator-blinded trial. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(4):1103–10.

Tan J, Blume-Peytavi U, Ortonne JP, et al. An observational cross-sectional survey of rosacea: clinical associations and progression between subtypes. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:555–62.

Tan J, Almeida LM, Bewley A, et al. Updating the diagnosis, classification and assessment of rosacea: recommendations from the global ROSacea COnsensus (ROSCO) panel. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:431–8.

Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, Hata TR. Rosacea: part I. Introduction, categorization, histology, pathogenesis, and risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:749–58.

Wilkin J, Dahl M, Detmar M, et al. Standard classification of rosacea: report of the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee on the classification and staging of rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:584–7.

Zhao YA, Wu LP, Peng Y, et al. Retrospective analysis of the association between Demodex infestation and rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146(8):896–902.

van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Carter B, van der Linden MM, Charland L. Interventions for rosacea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD003262.

Stein L, Kircik L, Fowler J, et al. Efficacy and safety of ivermectin 1% cream in treatment of papulopustular rosacea: results of two randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled pivotal studies. J Drugs Dermatol 2014;13:316–23.

Dahl MV, Katz HI, Krueger GG, Millikan LE, Odom RB, Parker F, Wolf JE Jr, Aly R, Bayles C, Reusser B, Weidner M, Coleman E, Patrignelli R, Tuley MR, Baker MO, Herndon JH Jr, Czernielewski JM. Topical metronidazole maintains remissions of rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134(6):679–83.

Acknowledgements

Funding

No funding or sponsorship was received for this study or publication of this article. The article processing charges were funded by the authors.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Chiel Cristiano F. Ebbelaar, Aalt W. Venema, and Maria R. Van Dijk have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This review is based on previously conducted studies and does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced digital features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.6509759.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Ebbelaar, C.C.F., Venema, A.W. & Van Dijk, M.R. Topical Ivermectin in the Treatment of Papulopustular Rosacea: A Systematic Review of Evidence and Clinical Guideline Recommendations. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb) 8, 379–387 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-018-0249-y

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13555-018-0249-y