Abstract

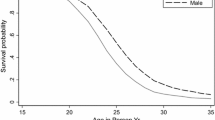

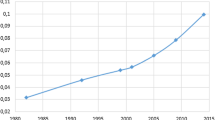

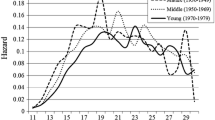

In Africa and elsewhere, educated women tend to marry later than their less-educated peers. Beyond being an attribute of individual women, education is also an aggregate phenomenon: the social meaning of a woman’s educational attainment depends on the educational attainments of her age-mates. Using data from 30 countries and 246 birth cohorts across sub-Saharan Africa, we investigate the impact of educational context (the percentage of women in a country cohort who ever attended school) on the relationship between a woman’s educational attainment and her marital timing. In contexts where access to education is prevalent, the marital timing of uneducated and highly educated women is more similar than in contexts where attending school is limited to a privileged minority. This across-country convergence is driven by uneducated women marrying later in high-education contexts, especially through lower rates of very early marriages. However, within countries over time, the marital ages of women from different educational groups tend to diverge as educational access expands. This within-country divergence is most often driven by later marriage among highly educated women, although divergence in some countries is driven by earlier marriage among women who never attended school.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Throughout this article, “convergence” and “divergence” refer exclusively to a narrowing or widening of the gap in across-group means, rather than to a reduction or increase in variance.

Two countries in our sample implemented policy changes during the observation period that altered their years-to-credential requirements. In Kenya, an eighth year of primary school was added; in Ethiopia, years seven and eight, previously part of junior secondary school, were reclassified as primary school. We allow the relationship between years of schooling and educational attainment categories to change across cohorts in order to reflect these policy changes, while acknowledging that these changes may themselves influence our outcome.

See Bongaarts et al. (2017) for a recent application of decomposition to examine marital age trends.

We tested this assumption separately for each country using Schoenfield residuals for individual-level educational attainment. Of 90 country-specific education categories, this assumption was violated nine times. In these nine cases, graphs revealed that the education-level residual trend lines did not cross one another and were sloped only at extreme ends of the marital age distribution (less than 14 and greater than 35). Thus, even in these cases, the estimated parameters still yield a weighted average of the effect over most of the observed age range but will conceal how the effect differs for very early or delayed marriage ages (Lundborg et al. 2016).

For a more extensive investigation of differences by urban/rural status, see online appendix 1.

This model, which estimates clustered standard errors at the country-cohort level but does not include frailty terms for countries or cohorts, is presented in online appendix 4. The mean absolute difference in hazard ratios between our main model and this alternate specification is very small (0.01), so survival estimates from this model are instructive for understanding our main results.

This conclusion can also be drawn from the fact that in the full model, between-country variance is substantially larger than within-country, between-cohort variance (Table 1).

We find this result puzzling, but we suggest two possible explanations. First, our data reach back further in time for Namibia (to women born in 1942) than for most countries, and educational differences may have been less distinguishing in this era. Second, this earliest cohort of women contains only 34 women with completed secondary school, so the estimate is based on an unusually small cell size.

References

Allison, P. D. (2014). Event history and survival analysis: Regression for longitudinal event data (Vol. 46). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Arnaldo, C. (2004). Ethnicity and marriage patterns in Mozambique. African Population Studies, 19(1). Retrieved from https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/handle/1807/3518

Baker, D. P. (2014). The schooled society: The educational transformation of global culture. Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press.

Behrman, J. A. (2015). Does schooling affect women’s desired fertility? Evidence from Malawi, Uganda, and Ethiopia. Demography, 52, 787–809.

Bledsoe, C. (1990). Transformations in sub-Saharan African marriage and fertility. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Scoial Science, 510, 115–125.

Blossfeld, H. P. (2009). Educational assortative marriage in comparative perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 513–530.

Bongaarts, J., Mensch, B. S., & Blanc, A. K. (2017). Trends in the age at reproductive transitions in the developing world: The role of education. Population Studies, 71, 1–16.

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1990). Reproduction in education, society and culture (Vol. 4). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Burke, C. (2015). Culture, capitals and graduate futures: Degrees of class. London, UK: Routledge.

Caldwell, J. C. (1980). Mass education as a determinant of the timing of fertility decline. Population and Development Review, 6, 225–255.

Cleland, J. (2002). Education and future fertility trends, with special reference to mid-transitional countries. In United Nations (Ed.), Completing the fertility transition (pp. 187–202). New York, NY: United Nations.

Colleran, H., Jasienska, G., Nenko, I., Galbarczyk, A., & Mace, R. (2014). Community-level education accelerates the cultural evolution of fertility decline. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 281, 20132732. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.2732

Cox, D. R., & Oakes, D. (1984). Analysis of survival data (Vol. 21). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Dixon-Mueller, R. (2008). How young is “too young”? Comparative perspectives on adolescent sexual, marital, and reproductive transitions. Studies in Family Planning, 39, 247–262.

Esteve, A., López-Ruiz, L. Á., & Spijker, J. (2013). Disentangling how educational expansion did not increase women's age at union formation in Latin America from 1970 to 2000. Demographic Research, 28(article 3), 63–76. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2013.28.3

Foster, P. (1980). Education and social inequality in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Modern African Studies, 18, 201–236.

Gage, A. J., & Bledsoe, C. (1994). The effects of education and social stratification on marriage and the transition to parenthood in Freetown, Sierra Leone. In C. Bledsoe & G. Pison (Eds.), Nuptiality in sub-Saharan Africa (pp. 148–164). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Grant, M. J. (2015). The demographic promise of expanded female education: Trends in the age at first birth in Malawi. Population and Development Review, 41, 409–438.

Grant, M. J., & Hallman, K. K. (2008). Pregnancy-related school dropout and prior school performance in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Studies in Family Planning, 39, 369–382.

Gyimah, S. O. (2009). Cohort differences in women’s educational attainment and the transition to first marriage in Ghana. Population Research and Policy Review, 28, 455–471.

Hendi, A. S. (2015). Trends in U.S. life expectancy gradients: The role of changing educational composition. International Journal of Epidemiology, 44, 946–955.

Hendi, A. S. (2017). Trends in education-specific life expectancy, data quality, and shifting education distributions: A note on recent research. Demography, 54, 1–11.

ICF. (1988–2016). Demographic and Health Surveys [Data sets, various years]. Funded by USAID. Rockville, MD: ICF [Distributor].

Ikamari, L. D. (2005). The effect of education on the timing of marriage in Kenya. Demographic Research, 12(article 1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2005.12.1

Johnson-Hanks, J. (2006). Uncertain honor: Modern motherhood in an African crisis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Kaufmann, G. L., & Meekers, D. (1998). The impact of women’s socioeconomic position on marriage patterns in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 29, 101–114.

Koski, A., Clark, S., & Nandi, A. (2017). Has child marriage declined in sub-Saharan Africa? An analysis of trends in 31 countries. Population and Development Review, 43, 7–29.

Kravdal, Ø. (2002). Education and fertility in sub-Saharan Africa: Individual and community effects. Demography, 39, 233–250.

Kritz, M. M., & Gurak, D. T. (1989). Women’s status, education and family formation in sub-Saharan Africa. International Family Planning Perspectives, 15, 100–105.

Kroeger, R. A., Frank, R., & Schmeer, K. K. (2015). Educational attainment and timing to first union across three generations of Mexican women. Population Research and Policy Review, 34, 417–435.

Langsten, R. (2017). School fee abolition and changes in education indicators. International Journal of Educational Development, 53, 163–175.

Lundborg, P., Lyttkens, C. H., & Nystedt, P. (2016). The effect of schooling on mortality: New evidence from 50,000 Swedish twins. Demography, 53, 1135–1168.

Manda, S., & Meyer, R. (2005). Age at first marriage in Malawi: A Bayesian multilevel analysis using a discrete time-to-event model. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series A (Statistics in Society), 168, 439–455.

Mann, K. (1985). Marrying well: Marriage, status and social change among the educated elite in colonial Lagos. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Marteleto, L., Lam, D., & Ranchhod, V. (2008). Sexual behavior, pregnancy, and schooling among young people in urban South Africa. Studies in Family Planning, 39, 351–368.

McNay, K., Arokiasamy, P., & Cassen, R. (2003). Why are uneducated women in India using contraception? A multilevel analysis. Population Studies, 57, 21–40.

Meekers, D. (1992). The process of marriage in African societies: A multiple indicator approach. Population and Development Review, 18, 61–78.

Moursund, A., & Kravdal, Ø. (2003). Individual and community effects of women’s education and autonomy on contraception use in India. Population Studies, 57, 285–301.

Mu, Z., & Xie, Y. (2014). Marital age homogamy in China: A reversal of trend in the reform era? Social Science Research, 44, 141–157.

Neal, S. E., & Hosegood, V. (2015). How reliable are reports of early adolescent reproductive and sexual health events in Demographic and Health Surveys? International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 41, 210–217.

Nishimura, M., & Byamugisha, A. (2011). The challenges of universal primary education policy in sub-Saharan Africa. In W. Jacob & J. Hawkins (Eds.), Policy debates in comparative, international, and development education (pp. 225–245). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nishimura, M., Yamano, T., & Sasaoka, Y. (2008). Impacts of the universal primary education policy on educational attainment and private costs in rural Uganda. International Journal of Educational Development, 28, 161–175.

Qian, X., & Smyth, R. (2007). Measuring regional inequality of education in China: Widening coast-inland gap or widening rural-urban gap? Journal of International Development, 20, 132–144.

Raymo, J. M. (2003). Educational attainment and the transition to first marriage among Japanese women. Demography, 40, 83–103.

Raymo, J. M., & Iwasawa, M. (2005). Marriage market mismatches in Japan: An alternative view of the relationship between women’s education and marriage. American Sociological Review, 70, 801–822.

Rindfuss, R. R., Brewster, K. L., & Kavee, A. L. (1996). Women, work, and children: Behavioral and attitudinal change in the United States. Population and Development Review, 22, 457–482.

Rotman, A., Shavit, Y., & Shalev, M. (2016). Nominal and positional perspectives on educational stratification in Israel. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 43, 17–24.

Sahn, D. E., & Stifel, D. C. (2003). Urban-rural inequality in living standards in Africa. Journal of African Economics, 12, 564–597.

Schofer, E., & Meyer, J. W. (2005). The worldwide expansion of higher education in the twentieth century. American Sociological Review, 70, 898–920.

Schwartz, C. R., & Mare, R. D. (2005). Trends in educational assortative marriage from 1940 to 2003. Demography, 42, 621–646.

Singh, S., & Samara, R. (1996). Early marriage among women in developing countries. International Family Planning Perspectives, 22, 148–157, 175.

Stevens, M. L., Armstrong, E. A., & Arum, R. (2008). Sieve, incubator, temple, hub: Empirical and theoretical advances in the sociology of higher education. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 127–151.

Therneau, T. (2012). Coxme: Mixed effects Cox models (R package version 2.2–3). Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Theunynck, S. (2009). School construction strategies for universal primary education in Africa: Should communities be empowered to build their schools? Washington, DC: World Bank.

Thomas, V., Wang, Y., & Fan, X. (2001). Measuring education inequality: Gini coefficients of education (Working Paper 2525). Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank. (2009). Abolishing school fees in Africa: Lessons from Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, and Mozambique. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Yu, J., & Xie, Y. (2015). Changes in the determinants of marriage entry in post-reform urban China. Demography, 52, 1869–1892.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for helpful feedback from Sarah K. Cowan, Amal Harrati, Jennifer Johnson-Hanks, Jayanti Owens, Hyunjoon Park, Will Lowe, and Kenneth Wachter. Previous versions of this research were presented at the Population Association of America Annual Meeting (April 2017, Chicago, IL), the International Union of the Scientific Study of Population Annual Meeting (October 2017, Cape Town, South Africa), and the African Studies Works in Progress Series at Princeton University (April 2017, Princeton, NJ); and benefitted greatly from suggestions from members of the audience. Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number P2CHD047879. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(PDF 700 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Frye, M., Lopus, S. From Privilege to Prevalence: Contextual Effects of Women’s Schooling on African Marital Timing. Demography 55, 2371–2394 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0722-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-018-0722-3